Summary

In a multicenter, prospective case-control study involving 1758 children aged <5 years in developing and emerging countries, the main microorganisms associated with pneumonia were Streptococcus pneumoniae, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus.

Keywords: pneumonia, child, case-control studies, etiology, developing countries

Abstract

Background

Pneumonia, the leading infectious cause of child mortality globally, mainly afflicts developing countries. This prospective observational study aimed to assess the microorganisms associated with pneumonia in children aged <5 years in developing and emerging countries.

Methods

A multicenter, case-control study by the GABRIEL (Global Approach to Biological Research, Infectious diseases and Epidemics in Low-income countries) network was conducted between 2010 and 2014 in Cambodia, China, Haiti, India (2 sites), Madagascar, Mali, Mongolia, and Paraguay. Cases were hospitalized children with radiologically confirmed pneumonia; controls were children from the same setting without any features suggestive of pneumonia. Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected from all subjects; 19 viruses and 5 bacteria were identified by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Associations between microorganisms and pneumonia were quantified by calculating the adjusted population attributable fraction (aPAF) after multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for sex, age, time period, other pathogens, and site.

Results

Overall, 888 cases and 870 controls were analyzed; ≥1 microorganism was detected in respiratory samples in 93.0% of cases and 74.4% of controls (P < .001). Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza virus 1, 3, and 4, and influenza virus A and B were independently associated with pneumonia; aPAF was 42.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 35.5%–48.2%) for S. pneumoniae, 18.2% (95% CI, 17.4%–19.0%) for RSV, and 11.2% (95% CI, 7.5%–14.7%) for rhinovirus.

Conclusions

Streptococcus pneumoniae, RSV, and rhinovirus may be the major microorganisms associated with pneumonia infections in children <5 years of age from developing and emerging countries. Increasing S. pneumoniae vaccination coverage may substantially reduce the burden of pneumonia among children in developing countries.

Pneumonia is the leading infectious cause of child mortality and accounts for 1 million deaths annually, mainly in developing countries [1–3]. Implementation of more effective preventive vaccination policies and treatments may reduce pneumonia deaths in children <5 years old in developing countries [4]. However, better knowledge of pneumonia etiology is required. Indeed, vaccination policies should be regularly evaluated in the context of disease epidemiology. In many countries, treatments for infection are empiric due to insufficient microbiological diagnoses, at least in primary care. Therefore, up-to-date knowledge of pneumonia etiology in populations would help target empiric treatments to common microbial agents.

Most multicentric data on pneumonia etiology in developing countries is ancient [5]; Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are frequently described causative pathogens [6–8]. Several epidemiological factors, such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, implementation of vaccines at the national level—particularly pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) and Hib vaccine [9]—and secular trends may have modified the distribution of causative pathogens. In addition, new microorganisms, mainly viruses, have been discovered [10]. Moreover, diagnostic testing has undergone major improvements in sensitivity [11]. Therefore, multicenter, case-control studies of pneumonia etiology with asymptomatic controls are warranted [12].

The main objective of this prospective, multicenter, case- control study was to assess the microorganisms associated with pneumonia in children <5 years old in developing and emerging countries at the population level.

METHODS

Study Design and Ethics

A prospective, hospital-based, multicenter, case-control study of incident cases was implemented from May 2010 to June 2014 at 9 member sites of the GABRIEL (Global Approach to Biological Research, Infectious diseases and Epidemics in Low-income countries) Network in 8 countries: Cambodia (National Pediatric Hospital, Phnom Penh), China (Beijing Children’s Hospital, Beijing), Haiti (Tent City Hospital, Port-au-Prince), India (Pune site: KEM Hospital Research Center and Shirdi Sai Baba Rural Hospital; Lucknow site: Chatrapati Shahuji Maharaj University Hospital), Madagascar (Hôpital Femme-Mère-Enfant, Antananarivo), Mali (Gabriel Touré Hospital, Bamako), Mongolia (Bayanzurkh District General Hospital, Ulaanbaatar), and Paraguay (Hospital Pediátrico Niños de Acosta Ñu, San Lorenzo) [13]. Study protocol, informed consent statement, case report form, amendments, and study documents were approved locally by the institutional research ethics committee (Supplementary Materials 1 and 2) [14]). Databases were anonymized.

Definition of Cases and Controls

Eligible patients were identified by study clinicians at each site; all consecutive hospitalized patients were assessed for eligibility during every season over at least 1 year. Pneumonia cases had to fulfill all inclusion criteria: (1) hospitalized patients aged 2–60 months; (2) presenting with cough and/or dyspnea; (3) with tachypnea, as defined by the World Health Organization (breathing rate ≥50 cycles/minute at 2–12 months of age; ≥40 cycles/minute at 12–59 months of age) [15]; (4) first symptoms appearing in last 14 days; (5) radiological confirmation of primary end-point pneumonia following WHO guidelines [16]; and (6) informed consent statement signed by parents or legal guardian. Primary end-point pneumonia was confirmed by at least 1 medical reader at each study site as the presence of end-point consolidation on chest radiograph, or pleural effusion in lateral pleural space associated with pulmonary parenchymal infiltrate, or effusion large enough to obscure such opacity [16]. Wheezing was initially an exclusion criterion for cases, but was withdrawn in all countries as it created difficulty in enrolling patients.

Inclusion criteria for controls were (1) no signs/symptoms of respiratory illness/upper respiratory tract infection; (2) 2–60 months of age; (3) hospitalized for surgery or attending routine outpatient appointment (mild illnesses, routine monitoring, immunization, etc) at hospital site; and (4) informed consent signed by parents or legal guardian. Originally, we planned to include 1 control per case with matching by age (<24 vs ≥24 months) and date of admission (±1 month). As this goal was not achieved in some countries (overall individual matching, 52.7%), frequency-matched pooled analysis [17] was performed by site, age, and period of admission.

Biological Samples

Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected using Flexible minitip flocked swabs (Copan Diagnostics, Murrieta, California) from all individuals within 48 hours of admission, and processed similarly at each site. Nineteen viruses and 5 bacteria were detected using reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR; Fast-Track Diagnostics, Respiratory Pathogens 21 Plus, Luxembourg). A centralized, blinded, quality control PCR respiratory validation panel was provided to all sites before specimens were processed locally.

Urine, whole blood, and pleural effusions (in cases of pleurisy) were collected from cases within 48 hours of admission. Urine samples were subjected to antibiotic testing; whole blood were subjected to blood counts, blood culture, RT-PCR to identify Staphylococcus aureus and S. pneumoniae and Hib, serum C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin (PCT); pleural effusions were processed as respiratory specimens. There was no systematic HIV screening; HIV-infected children had known seropositive status at admission.

Statistical Methods

Pooled analysis aimed to include 1000 cases and 1000 controls to yield a 90% power to detect odds ratios (ORs) ≥2 with ≥5% exposure in controls, regardless of exposure prevalence in cases. Categorical variables were reported as numbers (percentages) and compared using the χ2 test; continuous variables were reported as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) and Student t test or 1-way analysis of variance.

Unconditional regression was performed as partial matching increases power and is generally efficient [17, 18]. Multivariate logistic regression was used to quantify associations between microorganisms detected in nasopharyngeal swabs and pneumonia risk. Multivariate models were first adjusted for sex, age category, time period (per quarter), and site; additionally adjusted for all microorganisms detected in nasopharyngeal swabs; then stratified by age category using separate models. Finally, multivariate logistic modeling was undertaken by site adjusting for sex, age category, time period, and other microorganisms. Adjusted population attributable fraction (aPAF) was calculated for upper respiratory samples as blood RT-PCR data were not available for controls. Conceptually, aPAF estimates proportional reduction if an individual pathogen is absent [19], and was calculated with “punafcc” function of Stata using adjusted OR (aOR) of multivariate models adjusted for all pathogens tested for pooled analysis, as in site- and age-stratified analysis [20]. Among pneumonia cases positive for a particular pathogen, the proportion of disease not attributable to the background rate is 1 – (1/aOR), that is, attributable risk fraction. The fraction of pneumonia cases that can be attributed to this pathogen (aPAF) is given by the proportion of cases positive for this pathogen multiplied by attributable risk fraction (Supplementary Materials 3).

Sensitivity analyses assessed putative selection bias. Multivariate logistic modeling was performed to calculate aPAF by excluding each site individually (1 site each time), then excluding cases with wheezing or antibiotics detected in urine. All tests were 2-tailed; P < .05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata software version 13.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). Missing data were avoided by performing complete case analysis for respiratory samples; other sample characteristics with missing data were included and described.

RESULTS

Study Population

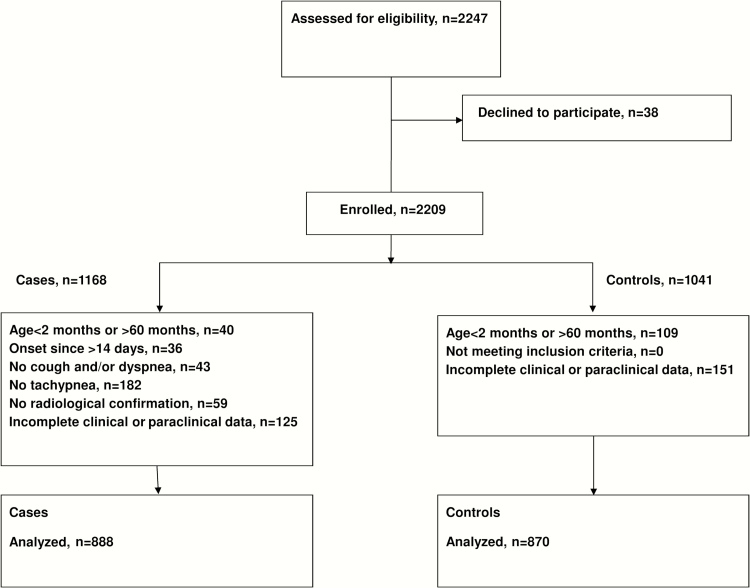

Of 2247 eligible children, 1758 patients (888 pneumonia cases, 870 controls) were analyzed (Figure 1). Proportion of individuals excluded after reassessment of inclusion criteria ranged from 0.5% (Mongolia, Paraguay) to 27.2% (China). Overall, 1024 (58.2%) children were male; mean age was 20.8 (SD, 15.4) months. Nineteen (1.2%) patients were HIV-infected. Table 1 describes study population characteristics by group and site. We identified imbalances between cases and controls by season in some countries; therefore, multivariate analyses were adjusted for season. Pneumonia cases had lower weight-for-height z scores (P < .001) and vaccination coverage (P < .001; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of selection and inclusion of cases and controls.

Table 1.

Description of Study Populations by Country and Group (N = 1758)

| Characteristic | Cambodia | China | Haiti | India (Lucknow) | India (Pune) | Madagascar | Mali | Mongolia | Paraguay | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | ||

| No. of children | 176 | 95 | 39 | 138 | 101 | 122 | 96 | 96 | 71 | 70 | 80 | 60 | 118 | 93 | 108 | 93 | 99 | 100 | |

| Date of inclusion, median | 30/01/11 | 24/01/11 | 20/12/11 | 05/07/11 | 22/04/13 | 12/06/13 | 07/02/13 | 19/02/13 | 10/04/13 | 26/06/13 | 20/09/11 | 03/04/12 | 14/11/12 | 10/11/11 | 09/03/12 | 28/03/12 | 25/11/11 | 22/11/11 | |

| Minimum | 21/10/10 | 3/11/10 | 17/02/11 | 04/08/10 | 24/04/12 | 26/04/12 | 07/08/12 | 07/08/12 | 23/06/12 | 25/06/12 | 17/01/11 | 29/12/10 | 04/07/11 | 11/07/11 | 22/09/11 | 07/10/11 | 18/05/10 | 14/09/10 | |

| Maximum | 02/01/13 | 21/3/11 | 15/08/12 | 14/12/12 | 06/11/13 | 24/10/13 | 06/12/13 | 13/08/13 | 05/03/14 | 03/06/14 | 15/02/13 | 13/08/13 | 20/12/11 | 27/12/12 | 25/10/12 | 30/10/12 | 20/05/13 | 27/05/13 | |

| Categorical variables, No. (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sex, male | 110 (62.5) | 41 (43.1) | 28 (71.8) | 82 (59.4) | 58 (57.4) | 68 (55.7) | 63 (65.6) | 57 (59.4) | 42 (59.1) | 43 (61.4) | 43 (53.7) | 38 (63.3) | 61 (51.7) | 57 (61.3) | 66 (61.1) | 55 (59.1) | 56 (56.6) | 56 (56.0) | |

| Age category | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2–11 mo | 70 (39.8) | 32 (33.3) | 17 (43.6) | 20 (14.6) | 41 (40.6) | 44 (36.1) | 33 (34.4) | 27 (38.0) | 27 (38.0) | 28 (40.0) | 23 (28.7) | 27 (43.5) | 56 (47.5) | 51 (54.8) | 27 (25.0) | 24 (25.8) | 39 (39.4) | 37 (37.0) | |

| 12–23 mo | 63 (35.8) | 31 (32.3) | 8 (20.5) | 26 (18.9) | 30 (29.7) | 40 (32.8) | 15 (15.6) | 24 (33.8) | 24 (33.8) | 22 (31.4) | 26 (32.5) | 18 (29.0) | 22 (18.6) | 19 (20.4) | 36 (33.3) | 33 (35.5) | 32 (32.3) | 37 (37.0) | |

| 24–60 mo | 43 (24.4) | 33 (34.4) | 14 (35.9) | 91 (66.4) | 30 (29.7) | 38 (31.1) | 48 (50.0) | 20 (28.2) | 20 (28.2) | 20 (28.6) | 31 (38.7) | 17 (27.4) | 40 (33.9) | 23 (24.7) | 45 (41.7) | 36 (38.7) | 28 (28.3) | 26 (26.0) | |

| Quarter | |||||||||||||||||||

| January–March | 45 (25.6) | 69 (71.9) | 18 (46.1) | 19 (13.8) | 9 (9.0) | 23 (24.0) | 23 (24.0) | 19 (19.8) | 11 (15.5) | 10 (14.3) | 28 (35.0) | 16 (26.3) | 28 (23.7) | 9 (9.7) | 30 (27.8) | 24 (25.8) | 10 (10.1) | 10 (10.1) | |

| April–June | 25 (14.2) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (25.6) | 29 (21.0) | 42 (42.0) | 22 (22.9) | 22 (22.9) | 25 (26.0) | 6 (8.4) | 8 (11.4) | 11 (13.7) | 21 (34.4) | 12 (10.2) | 9 (9.7) | 21 (19.4) | 20 (21.5) | 31 (31.3) | 31 (31.3) | |

| July–September | 4 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.3) | 46 (33.3) | 20 (20.0) | 24 (25.0) | 24 (25.0) | 26 (27.1) | 34 (47.9) | 36 (51.4) | 25 (31.2) | 16 (26.3) | 55 (46.6) | 20 (21.5) | 21 (19.4) | 19 (20.4) | 34 (34.3) | 28 (28.3) | |

| October–December | 102 57.9) | 27 (28.1) | 7 (18·0) | 44 (31.9) | 29 (29.0) | 27 (28.1) | 27 (28.1) | 26 (27.1) | 20 (28.2) | 16 (22.9) | 16 (20.0) | 8 (13.1) | 23 (19.5) | 55 (59.1) | 36 (33.3) | 30 (32.3) | 24 (24.2) | 30 (30.3) | |

| HIV+ | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0·0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (6.0) | 8 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Heart disease | 4 (2.3) | … | 3 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (3.3) | 4 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (8.1) | 9 (9.5) | |

| Weight-for-height z score ≤2 SD | 34 (21.4) | 10 (10.9) | 3 (7.7) | 6 (4.4) | 35 (34.6) | 22 (18.2) | … | 39 (40.6) | 30 (42.2) | 12 (17.1) | 37 (46.2) | 24 (40.7) | 41 (34.7) | 41 (44.1) | 3 (2.8) | 2 0.1) | 17 (17.2) | 5 (6.8) | |

| Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine | … | … | … | … | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (28.1) | 1/47 (2.1) | 0/49 (0.0) | 3/73 (4.1) | 2/52 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16/71 (22.5) | 22/79 (27.8) | |

| DPT-HBV-Hib vaccine, 1 dose | … | … | … | … | 66/70 (94.3) | 99/101 (98.0) | 2 (2.1) | 48 (50.0) | 59 (83.1) | 61 (87.1) | 69/72 (95.8) | 53/53 (100) | 102 (86.4) | 80 (86.0) | 107 99.1) | 92 (98.9) | 65/66 (98.5) | 82/86 (95.3) | |

| DPT-HBV-Hib vaccine, 3 doses | … | … | … | … | 44/64 (68.7) | 80/101 (79.2) | 2 (2.1) | 23 (24.0) | 47 (66.2) | 52 (74.3) | 64/71 (90.1) | 48/53 (90.6) | 81 (68.6) | 69 (74.2) | 103 (95.4) | 92 (9.9) | 51/52 (98.1) | 60/83 (72.3) | |

| Influenza vaccine | … | … | … | … | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0/73 (0.0) | 1/48 (2.1) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 19/63 (30.2) | 29/71 (40.8) | |

| Continuous variables, mean (SD) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Age, mo | 16.9 (11.3) | 22.4 (17.8) | 19.6 (17.0) | 29.8 (16.6) | 18.9 (13.6) | 20.0 (13.7) | 26.1 (19.7) | 27.4 (19.9) | 17.6 (12.2) | 19.2 (13.9) | 22.2 (14.6) | 17.1 (12.6) | 17.7 (14.7) | 14.8 (12.7) | 23.5 (14.6) | 22.9 (14.5) | 17.8 (13.1) | 16.9 (13.2) | |

| Weight-for-height z score | –1.1 (1.4) | –0.6 (1.6) | 0.1 (2.0) | 0.2 (1.5) | –1.6 (1.6) | –0.7 (1.6) | … | –2.0 (1.4) | –1.8 (1.5) | –0.8 (1.3) | –2.0 (1.4) | –1.8 (1.5) | –1.7 (1.7) | –2.0 (1.7) | 0.2 (1.0) | –1.0 (4.9) | –0.3 (1.8) | 0.0 (1.3) | |

Abbreviations: DPT-HBV-Hib, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis–hepatitis B virus–polio–Haemophilus influenzae type b; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics Between Pneumonia Cases and Controls in the Entire Population (N = 1758)

| Characteristic | Pneumonia Cases (n= 888) | Controls (n = 870) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical variables, No. (%) | |||

| Sex, male | 527 (59.3) | 497 (57.3) | .39 |

| Age category | |||

| 2–11 mo | 333 (37.5) | 294 (33.8) | .08 |

| 12–23 mo | 256 (28.8) | 239 (27.5) | |

| 24–60 mo | 299 (38.7) | 336 (38.7) | |

| Quarter | |||

| January–March | 202 (22.8) | 195 (22.5) | .98 |

| April–June | 180 (20.3) | 180 (20.8) | |

| July–September | 221 (24.9) | 220 (25.4) | |

| October–December | 284 (32.0) | 270 (31.2) | |

| HIV+ | 9/758 (1.2) | 10/819 (1.2) | .95 |

| Heart disease | 39/886 (4.4) | 11/767 (1.4) | <.001 |

| Weight-for-height z score ≤2 SD | 200/775 (25.8) | 161/835 (19.3) | .002 |

| Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine | 21/614 (3.4) | 51/584 (8.7) | <.001 |

| DPT-HBV-Hib vaccine, 1 dose | 470/601 (78.2) | 515/592 (87.0) | <.001 |

| DPT-HBV-Hib vaccine, 3 doses | 392/580 (67.6) | 424/589 (72.0) | .10 |

| Influenza vaccine | 20/532 (3.8) | 30/593 (5.1) | .29 |

| Continuous variables, mean (SD) | |||

| Age, mo | 19.8 (14.6) | 21.8 (16.0) | .007 |

| Weight-for-height z score | –1.1 (1.7) | –0.7 (2.4) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: DPT-HBV-Hib, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis–hepatitis B virus–polio–Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SD, standard deviation.

Among cases, 19.3% had wheezing, 70.5% tested positive for urinary antibiotics at admission, and 46.6% received oxygen therapy. At admission, median body temperature was 38.3°C (IQR, 37.7°C–38.8°C), median breathing rate was 54 cycles/minute (IQR, 46–60 cycles/minute), median serum CRP was 26.3 mg/L (IQR, 7.5–88.4 mg/L), median serum PCT was 0.46 ng/mL (IQR, 0.09–3.4 ng/mL), and median white blood cell count was 13.0 × 109 cells/L (IQR, 7.4–20.9 × 109 cells/L).

Microbiological Analysis of Nasopharyngeal Samples From Cases and Controls

In nasopharyngeal samples, ≥1 microorganism was detected in 826 (93.0%) cases and 647 (74.4%) controls (P < .001), ≥1 bacteria in 660 (74.3%) cases and 525 (60.3%) controls (P < .001), ≥1 virus in 695 (78.3%) cases and 436 (50.1%) controls (P < .001), and mixed viral/bacterial detections in 529 (59.6%) cases and 314 (36.1%) controls (P < .001).

In cases, no differences were observed with respect to sex, age category, weight-for-height z score, PCV vaccination rate, serum PCT, serum CRP, and in-hospital mortality according to type of infection detected in nasopharyngeal swabs (viral, bacterial, mixed viral/bacterial).

Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, human metapneumovirus (hMPV), rhinovirus, RSV, parainfluenza virus 1, 3, and 4, and influenza virus A and B were independently associated with pneumonia risk (Table 3; Supplementary Table 1). Influenza virus A was most strongly associated (aOR, 55.2 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 7.4–411.3]), followed by hMPV and RSV (aORs, 11.0 [95% CI, 5.4–22.3] and 11.7 [95% CI, 7.4–18.5], respectively). Streptococcus pneumoniae and H. influenzae were positively associated; however, these associations were weaker and varied by age (Table 3; Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3.

Microbiological Findings for Respiratory Samples From Pneumonia Cases and Controls (N = 1758)

| Microorganism | Pneumonia Cases (n = 888) | Controls (n = 870) | aORa (95% CI), Not Adjusted for Other Microorganisms | aORb (95% CI), Adjusted for Other Microorganisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 605 (68.2) | 412 (47.5) | 2.5 (2.0–3.1) | 2.6 (2.0–3.3) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 107 (12.1) | 148 (17.0) | 0.7 (.5–.9) | 0.8 (.5–1.1) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 47 (5.3) | 57 (6.6) | 1.2 (.7–1.8) | 1.1 (.7–1.9) |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 13 (1.5) | 6 (0.7) | 4.1 (1.4–11.9) | 9.2 (2.5–33.5) |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | 4 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) | 1.8 (.3–10.1) | 2.1 (.3–13.4) |

| Viruses | ||||

| hMPV | 76 (8.6) | 10 (1.1) | 7.0 (3.5–13.7) | 11.0 (5.4–22.3) |

| Coronavirus 63 | 10 (1.1) | 18 (2.1) | 0.6 (.3–1.3) | 1.0 (.4–2.5) |

| Coronavirus 229 | 7 (0.8) | 9 (1.0) | 0.8 (.3–2.2) | 0.7 (.2–2.4) |

| Coronavirus 43 | 20 (2.2) | 33 (3.8) | 0.7 (.4–1.3) | 0.7 (.4–1.4) |

| Coronavirus HKU | 23 (2.6) | 16 (1.9) | 1.4 (.7–2.7) | 1.7 (.8–3.5) |

| Adenovirus | 68 (7.7) | 65 (7.5) | 1.2 (.8–1.7) | 1.3 (.8–2.0) |

| Enterovirus | 42 (4.7) | 38 (4.4) | 1.1 (.7–1.8) | 1.5 (.8–2.5) |

| Parechovirus | 21 (2.4) | 13 (1.5) | 1.7 (.8–3.6) | 1.5 (.6–4.0) |

| Rhinovirus | 221 (24.9) | 188 (21.6) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 1.8 (1.4–2.4) |

| RSV | 178 (20.0) | 34 (3.9) | 7.8 (5.1–11.7) | 11.7 (7.4–18.5) |

| PIV1 | 26 (2.9) | 9 (1.0) | 3.8 (1.7–8.4) | 7.5 (2.9–19.7) |

| PIV2 | 4 (0.4) | 5 (0.6) | 1.0 (.2–4.0) | 2.0 (.3–12.8) |

| PIV3 | 57 (6.4) | 18 (2.1) | 3.8 (2.2–6.7) | 6.7 (3.6–12.6) |

| PIV4 | 21 (2.4) | 12 (1.5) | 1.9 (.9–3.9) | 2.6 (1.1–6.0) |

| Influenza virus A | 59 (6.6) | 4 (0.5) | 17.2 (6.1–48.3) | 55.2 (7.4–411.3) |

| Influenza virus B | 26 (2.9) | 11 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.2–5.3) | 3.3 (1.5–7.3) |

| Influenza virus A/ H1N1 | 24 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | NE | NE |

| Bocavirus | 82 (9.2) | 104 (11.9) | 0.7 (.5–1.0) | 0.6 (.4–.9) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; hMPV, human metapneumovirus; NE, not estimable; PIV, parainfluenza virus RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

aAfter multivariate logistic regression, adjusted for sex, age category (2–11, 12–23, 24–60 months), time period (per quarter), and site.

bAfter multivariate logistic regression, adjusted for sex, age category (2–11, 12–23, 24–60 months), time period (per quarter), site, and other pathogens from respiratory sample.

Additional Microbiological Findings in Cases

In blood RT-PCR, 8.3% (74/888), 2.7% (24/887), and 1.8% (13/711) of cases were positive for S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and S. aureus, respectively. Eighty cases (9.0%) were positive on blood culture, 56 possibly attributed to bacterial contamination. Salmonella species (n= 5 [0.6%]), S. pneumoniae (n= 4 [0.5%]), S. aureus (n= 4 [0.5%]), Hib (n = 1 [0.1%]), Acinetobacter baumannii (n= 1 [0.1%]), Enterobacter cloacae (n= 1 [0.1%]), Enterococcus faecium (n= 1 [0.1%]), Escherichia coli (n= 1 [0.1%]), Neisseria meningitidis (n= 2 [0.2%]), and gram-positive bacilli (n= 4 [0.5%]) were detected in blood cultures. Among cases with positive blood culture, 50% (2/4), 0% (0/4), and 25% (1/4) were also positive for the same species (S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, Hib, respectively) in blood PCR.

Pleural samples were obtained from 26 (2.9%) cases, of whom 50% had ≥1 microorganism detected: S. pneumoniae (n= 12), S. aureus (n= 1), adenovirus (n= 1), or bocavirus (n= 1). Most cases (83.8%) positive for S. pneumoniae on blood RT-PCR were positive for this species in respiratory samples (P = .003); 10 cases (83.3%) were PCR positive for S. pneumoniae in both pleural and respiratory samples.

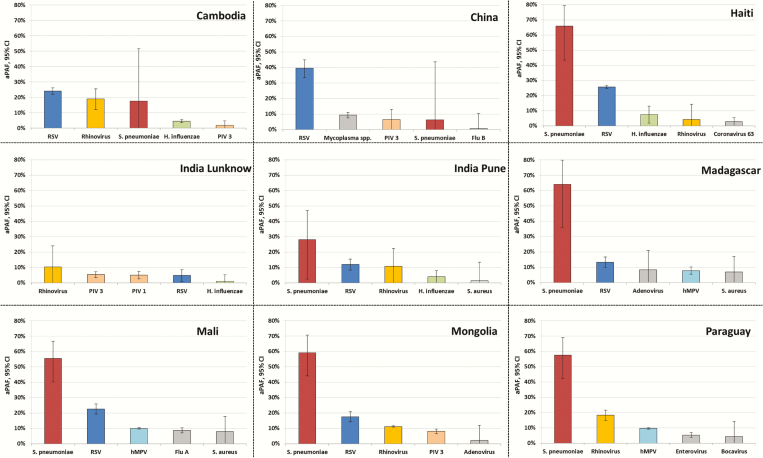

Adjusted Population Attributable Fraction

Streptococcus pneumoniae had the highest aPAF (42.2% [95% CI, 35.5%–48.2%]) in pooled analysis; this value was consistent regardless of age (Table 4; Supplementary Figure 1). RSV had the second-highest aPAF; an inverse relationship was observed between RSV pneumonia and age. Rhinovirus had the third highest aPAF, but was not independently associated with pneumonia in younger children (2–11 months). Streptococcus pneumoniae was the main bacterium associated with pneumonia in most countries, except Cambodia, China, and India (Lucknow site) (Figure 2). RSV and hMPV were also significant agents; other pathogens were selectively coupled with pneumonia in some countries.

Table 4.

Adjusted Population Attributable Fraction of Microorganisms Associated With Pneumonia in Children in the Pooled Analysis of Respiratory Samples (N = 1758)

| Microorganism | aPAF, % (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overalla | 2–11 mob | 12–23 mob | 24–60 mob | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 42.2 (35.5–48.2) | 43.5 (33.6–51.9) | 44.4 (28.4–56.8) | 41.6 (30.6–50.9) |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 18.2 (17.4–19.0) | 24.6 (23.5–25.7) | 16.6 (15.2–18.0) | 11.0 (8.6–13.3) |

| Rhinovirus | 11.2 (7.5–14.7) | 4.2 (–5.0 to 12.6) | 14.2 (8.4–19.6) | 10.7 (3.8–17.1) |

| Human metapneumovirus | 7.8 (7.2–8.3) | 6.4 (5.1–7.7) | 9.9 (8.8–10.9) | 7.1 (6.2–8.1) |

| Influenza virus A | 6.5 (6.4–6.7) | NE | 5.4 (5.1–5.7) | NE |

| Parainfluenza virus 3 | 5.5 (4.9–6.1) | 4.5 (3.2–5.7) | 8.3 (7.3–9.2) | 4.6 (3.8–5.3) |

| Parainfluenza virus 1 | 2.6 (2.2–2.9) | NE | NE | 1.3 (.4–2.2) |

| Influenza virus B | 2.1 (1.3–2.8) | 1.9 (.7–3.1) | 3.3 (1.9–4.7) | 1.1 (–.3 to 2.6) |

| Adenovirus | 1.7 (–.8 to 4.2) | 3.1 (–.2 to 6.3) | 0.0 (–6.0 to 5.7) | NE |

| Enterovirus | 1.5 (–.3 to 3.3) | –2.7 (–7.7 to 2.1) | 5.4 (3.5–7.3) | 2.8 (–.3 to 5.8) |

| Parainfluenza virus 4 | 1.5 (.7–2.2) | 1.5 (.0–3.0) | 2.3 (1.3–3.2) | 0.8 (–.5 to 2.2) |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | NE | 0.7 (.5–.9) | 2.1 (1.7–2.6) |

| Coronavirus HKU | 1.0 (–.1 to 2.1) | 1.5 (.5–2.5) | –0.6 (–3.6 to 2.4) | 0.6 (–3.3 to 4.3) |

| Parechovirus | 0.8 (–.7 to 2.3) | 0.2 (–2.8 to 3.1) | –1.3 (–7.7 to 4.7) | 2.8 (2.2–3.5) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 0.5 (–2.1 to 3.0) | 2.2 (.1–4.3) | 4.4 (1.4–7.3) | –3.9 (–11.5 to 3.2) |

Abbreviations: aPAF, adjusted population attributable fraction; CI, confidence interval; NE, not estimable.

aAfter multivariate logistic regression, adjusted for sex, age category (2–11, 12–23, 24–60 months), time period (per quarter), site, and presence of other pathogens.

bAfter multivariate logistic regression, adjusted for sex, age category (2–11, 12–23, 24–60 months), time period (per quarter), site, and presence of other pathogens (including Staphylococcus aureus; Chlamydia pneumoniae; parainfluenza virus 2; coronavirus 43, 63, and 229; bocavirus). Microorganisms with aPAF values <0.5% are not shown.

Figure 2.

Five leading microorganisms associated with pneumonia in children at each study site based on the adjusted population attributable fraction (aPAF) of respiratory samples. After multivariate logistic regression, adjusted for sex, age category (2–11, 12–23, 24–60 months), time period (per quarter), and presence of other pathogens. The 5 microorganisms with the highest aPAF fractions per site are shown (with 95% confidence intervals). Abbreviations: aPAF, adjusted population attributable fraction; CI, confidence interval; hMPV, human metapneumovirus; PIV, parainfluenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Sensitivity Analysis

The aPAF values varied from +3.8% to –7.4% (mostly within ±1%) when individual sites were excluded (Supplementary Figure 2). Exclusion of cases with wheezing or antibiotic-positive urine did not substantially affect estimations, except for RSV when antibiotic-positive cases were excluded (Supplementary Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

This prospective, multicenter, case-control study identified microorganisms associated with pneumonia in children <5 years old in developing and emerging countries with low PCV coverage. Streptococcus pneumoniae, hMPV, rhinovirus, RSV, parainfluenza virus 1, 3, and 4, influenza virus A and B, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae were associated with pneumonia risk, independent of sex, age, time period, detection of other pathogens, and site. Streptococcus pneumoniae had the highest aPAF.

Detection of S. pneumoniae in respiratory samples from cases can indicate infection or colonization. Pneumococcal carriage is linked to several risk factors, including age or family size [21]. While the models accounted for age, site, sex, and time period, residual confounders may exist. Pneumococci are commonly recognized as the primary etiology of pneumonia [22]. Pneumococcus vaccines have dramatically decreased the incidence of pediatric pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae in the United States [23], but only recently been introduced in several developing and emerging countries: 138 (71%) countries had introduced PCV by December 2016 (≤2 years ago in 20 countries). However, most countries would achieve the same coverage of PCV as diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis–hepatitis B–polio–Hib vaccine. Therefore, preventive measures against S. pneumoniae—mainly vaccination—should be a priority. While PCV coverage was higher in controls, this study was not designed to analyze vaccine effectiveness [24]. WHO radiographic criteria for pneumonia were defined as a robust endpoint for PCV and Hib vaccine trials. This may bias our results toward bacterial causes, as viral pneumonia is less likely to present with lobar consolidation or effusion. However, we aimed to focus primarily on severe pneumonia requiring hospitalization. Most study sites had very low PCV vaccine coverage. Epidemiology may vary in developing countries with higher vaccination coverage; it would be useful to reassess pneumonia etiology in a few years to evaluate the impact of PCV vaccination.

RSV was the main viral agent associated with pneumonia (aPAF, 18.2%); consistent with a previous meta-analysis showing that RSV causes 20% of acute lower respiratory infections [8]. RSV detection decreased with age, in accordance with recent findings in other settings with a different source population and case definition [25]. In our population, rhinovirus was significantly associated with pneumonia, with a high detection rate in controls. Rhinovirus was detected in 27% of American children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia [25]. While under debate, growing evidence suggests a causal role for rhinovirus in pneumonia etiology [26–28]. Human metapneumovirus may also be important, and has been described as a common respiratory pathogen in children (particularly <1 year of age) accounting for 5%–10% of pediatric acute respiratory infection hospitalizations [29, 30]. Though frequently described to be an agent [31], Haemophilus influenzae was not significantly associated with pneumonia; high Hib vaccination coverage could explain this finding.

The aPAF is widely employed for chronic diseases, but rarely infectious diseases [21, 22], and is based on 2 parameters: prevalence of test positivity among cases and odds ratio. Its interpretation in infectious disease epidemiology is less demonstrated. In addition, most pneumonia investigations did not include control groups to account for carriage prevalence and imperfect tests. Thus, detection of several microorganisms in nasopharyngeal samples does not confirm a causative role. Blood RT-PCR results were not included in aPAF estimation, to prevent information bias [32]. Upper respiratory samples—although not specific enough to diagnose etiology at the individual level as samples are distant from the disease site—may help infer pneumonia etiology at the population level. This approach, which seeks to control the causes of incidence, is complementary to case-centered epidemiology and may guide global preventive strategies [33]. Multivariate models were adjusted for all pathogens tested, meaning that pathogens significantly or not significantly associated with pneumonia were retained. Nonsignificant results for some microorganisms suggest a lack of power to detect weak associations, the effect of chance (ie related to study samples), or bias. Advanced molecular diagnostic tools may be useful for epidemiological purposes, though their imperfect sensitivity and specificity may induce confusion between carriage and infection and miss some true infections [34]. Some viral agents were detected in upper respiratory samples consistently more often in cases than controls at all sites, with low detection rates in controls. However, detection of other viruses or bacteria using molecular diagnostic tools contributes little to clinical management [35]. In addition, the sensitivity of a nasopharyngeal swab is likely to be higher for pneumonia cases because of larger mucous volumes due to symptoms such as coryza [34].

The main strengths of this study include prospective collection of standardized data with advanced molecular diagnostic techniques. While difficulties were encountered related to its multicultural context, this project enabled construction of a decentralized infectious disease research network in developing countries [13]. Multicentric design and inclusion of countries bearing the majority of global pneumonia burden would permit generalization of these results to other developing countries. We identified similarities in the leading pathogens across countries. Multivariate analysis accounted for baseline levels of carriage in controls and estimated the independent contribution of each pathogen. However, residual confounding might persist if the sensitivity of respiratory samples varies depending on the microorganism. Among pathogens with strong positive associations (eg, S. pneumoniae, RSV, hMPV), adjustment increased the OR, suggesting that other pathogens may be “protective” and simultaneously associated with index pathogen carriage—or other pathogens may be a pneumonia risk with a negative association between pathogens, as described for S. aureus and S. pneumoniae [21]. Finally, despite exclusion of patients with respiratory signs from controls, analyses permitted adjustment for respiratory carriage in non-infected children.

Limitations include limited power to track seasonality and differences between sites. The sample size was relatively small to estimate site-specific differences and the number of cases varied between sites, which could lead to geographical confounding. However, pooled analyses were adjusted by study site. Second, case definition was amended due to the difficulties of enrolling patients without wheezing, which could have jeopardized internal validity. However, the data remained robust in sensitivity analyses after successively excluding individual sites or cases with wheezing. Sensitivity analysis after exclusion of cases with prehospital antibiotic exposure suggests that the importance of S. pneumoniae and RSV in pneumonia might be underestimated and that of rhinovirus overestimated. Seasonal enrollment discrepancies were observed at some sites; although the multivariate models were adjusted for this potential limitation, residual cofounding might persist. Publication of the large Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health (PERCH) study will help assess the validity and causality of both studies [36]. In addition, a possible higher detection rate of bacteria—principally S. pneumoniae but possibly other microorganisms—in patients with coryza would lead to misclassification bias regarding this bacterium. Indeed, it may be easier to identify nucleic acid if the respiratory sample is voluminous. Finally, although causality is difficult to approach, our results are consistent with other estimations [1, 2].

In this pre-PCV population of children <5 years old from developing and emerging countries, almost half of pneumonia cases may be attributable to S. pneumoniae. Major viruses associated with pneumonia were RSV, rhinovirus, and hMPV. Additional longitudinal studies could test for larger numbers of bacteria and account for the poor sensitivity of blood cultures. While increased S. pneumoniae vaccination coverage would substantially reduce pneumonia burden in developing and emerging countries, other therapeutic measures should be considered.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments. We thank GABRIEL Network members Emilio Espinola and Rosa Guillen (Departamento de Biología Molecular y Genética, Universidad Nacional de Asuncion, Paraguay); Maitsetseg Chuluunbaatar, Budragchaagiin Dash-Yandag (Bayanzurkh District General Hospital, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia); Lili Ren (Ministry of Health Key Laboratory of Systems Biology of Pathogens and Dr Christophe Mérieux Laboratory, Beijing, China); Visal Pechchamnann (Rodolphe Mérieux Laboratory, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Health Sciences, Phnom Penh, Cambodia); Elsie Jean, Katiana Thermil, Sherlyne Dominique St-Vil (GHESKIO, Port-au-Prince, Haiti); Bénédicte Contamin (†deceased), Muriel Maeder, Henintsoa Rabezanahary (Centre d’Infectiologie Charles Mérieux, Antananarivo, Madagascar); Abdoul Aziz Diakite (CHU Gabriel Touré, Bamako, Mali); Bréhima Traore (Centre d’Infectiologie Charles Mérieux, Bamako, Mali); Anand Kawade and Ruchi Joshi (KEM Hospital Research Centre, Pune, India); Jean-Noël Telles, Alain Rajoharisan, and Jonathan Hoffmann (Emerging Pathogens Laboratory, Fondation Mérieux, Lyon, France). This protocol was developed on behalf of the GABRIEL Network: http://gabriel.globe-network.org. We specially thank the following experts: Delia Goletti, Samir K. Saha, Ron Dagan, and Werner Albrich. Editing by Andrea Devlin and Ovid M. Da Silva is acknowledged.

Disclaimer. The study funders had no role in data analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Financial support. This study was supported by the GABRIEL Network of Fondation Mérieux.

Potential conflicts of interest. A. B. has received travel grants and nonfinancial support from Fondation Mérieux. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

for the Global Approach to Biological Research, Infectious diseases and Epidemics in Low-income countries (GABRIEL) Network:

Emilio Espinola, Rosa Guillen, Maitsetseg Chuluunbaatar, Budragchaagiin Dash-Yandag, Lili Ren, Visal Pechchamnann, Elsie Jean, Katiana Thermil, Sherlyne Dominique, Bénédicte Contamin, Muriel Maeder, Henintsoa Rabezanahary, Abdoul Aziz Diakite, Bréhima Traore, Anand Kawade, Ruchi Joshi, Jean-Noël Telles, Alain Rajoharisan, Jonathan Hoffmann, Delia Goletti, Samir K. Saha, Ron Dagan, and Werner Albrich

References

- 1. Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000-13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet 2015; 385:430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walker CL, Rudan I, Liu L, et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet 2013; 381:1405–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Available at: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.CM100WORLD-CH9?lang=en Accessed 15 October 2014.

- 4. Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Walker N, et al. ; Lancet Diarrhoea and Pneumonia Interventions Study Group Interventions to address deaths from childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea equitably: what works and at what cost? Lancet 2013; 381:1417–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Selwyn BJ. The epidemiology of acute respiratory tract infection in young children: comparison of findings from several developing countries. Coordinated Data Group of BOSTID Researchers. Rev Infect Dis 1990; 12(suppl 8):S870–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O’Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, et al. ; Hib and Pneumococcal Global Burden of Disease Study Team Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet 2009; 374:893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Watt JP, Wolfson LJ, O’Brien KL, et al. ; Hib and Pneumococcal Global Burden of Disease Study Team Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet 2009; 374:903–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010; 375:1545–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scott JA. The preventable burden of pneumococcal disease in the developing world. Vaccine 2007; 25:2398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woo PCY, Lau SKP, Chu C, et al. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol 2005; 79:884–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rhedin S, Lindstrand A, Rotzén-Östlund M, et al. Clinical utility of PCR for common viruses in acute respiratory illness. Pediatrics 2014; 133:e538–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adegbola RA. Childhood pneumonia as a global health priority and the strategic interest of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 2):S89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Komurian-Pradel F, Grundmann N, Siqueira MM, et al. Enhancing research capacities in infectious diseases: The GABRIEL network, a joint approach to major local health issues in developing countries. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2013; 1:40–43. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Picot VS, Bénet T, Messaoudi M, et al. Multicenter case–control study protocol of pneumonia etiology in children: global approach to biological research, infectious diseases and epidemics in low-income countries (GABRIEL network). BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ayieko P, English M. Case management of childhood pneumonia in developing countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007; 26:432–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cherian T, Mulholland EK, Carlin JB, et al. Standardized interpretation of paediatric chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in epidemiological studies. Bull World Health Organ 2005; 83:353–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stürmer T, Brenner H. Degree of matching and gain in power and efficiency in case-control studies. Epidemiology 2001; 12:101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thomas DC, Greenland S. The efficiency of matching in case-control studies of risk-factor interactions. J Chronic Dis 1985; 38:569–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rockhill B, Newman B, Weinberg C. Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. Am J Public Health 1998; 88:15–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Newson RB. Attributable and unattributable risks and fractions and other scenario comparisons. Stata J 2013; 13:672–98. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bogaert D, van Belkum A, Sluijter M, et al. Colonisation by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in healthy children. Lancet 2004; 363:1871–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McIntosh K. Community-acquired pneumonia in children. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:429–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grijalva CG, Nuorti JP, Arbogast PG, Martin SW, Edwards KM, Griffin MR. Decline in pneumonia admissions after routine childhood immunisation with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the USA: a time-series analysis. Lancet 2007; 369:1179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Subaiya S, Dumolard L, Lydon P, Gacic-Dobo M, Eggers R, Conklin L. Global routine vaccination coverage, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:1252–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. ; CDC EPIC Study Team Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Papadopoulos NG. Do rhinoviruses cause pneumonia in children? Paediatr Respir Rev 2004; 5(suppl A):S191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Louie JK, Roy-Burman A, Guardia-Labar L, et al. Rhinovirus associated with severe lower respiratory tract infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009; 28:337–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bosch AA, Biesbroek G, Trzcinski K, Sanders EA, Bogaert D. Viral and bacterial interactions in the upper respiratory tract. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9:e1003057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edwards KM, Zhu Y, Griffin MR, et al. ; New Vaccine Surveillance Network Burden of human metapneumovirus infection in young children. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:633–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Panda S, Mohakud NK, Pena L, Kumar S. Human metapneumovirus: review of an important respiratory pathogen. Int J Infect Dis 2014; 25:45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sigaúque B, Vubil D, Sozinho A, et al. Haemophilus influenzae type b disease among children in rural Mozambique: impact of vaccine introduction. J Pediatr 2013; 163(1 suppl):S19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL.Modern epidemiology, 3rd ed Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins,2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol 2001; 30:427–32; discussion 433–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jartti T, Söderlund-Venermo M, Hedman K, Ruuskanen O, Mäkelä MJ. New molecular virus detection methods and their clinical value in lower respiratory tract infections in children. Paediatr Respir Rev 2013; 14:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Howie SRC, Morris GAJ, Tokarz R, et al. Etiology of severe childhood pneumonia in The Gambia, West Africa, determined by conventional and molecular microbiological analyses of lung and pleural aspirate samples. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:682–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levine OS, O’Brien KL, Deloria-Knoll M, et al. The Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health Project: a 21st century childhood pneumonia etiology study. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 2):S93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.