Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a newly emerged infectious disease, and a novel SARS-associated coronavirus (CoV) has been identified as a causative agent (1)(2)(3). Reliable and sensitive determination of the SARS CoV load would aid in the early identification of infected individuals, provide guidance for treatment (especially the use of steroid hormones and antiviral agents), and aid in monitoring of a patient’s clinical course and outcome.

Among the available tests, viral gene amplification by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) provides a relatively rapid and specific test for the diagnosis of individuals showing SARS-associated symptoms (4)(5). RT-PCR was successfully used to detect SARS CoV in nasopharyngeal aspirates, nasopharyngeal swabs, throat swabs, and broncheoalveolar lavage of SARS patients (6)(7). However, because the composition of these samples varies with time and among individuals, they are unlikely to serve as a standardized sample source for quantification, comparison, or monitoring of SARS CoV infection. To meet clinical needs, some improved RT-PCR methods have been developed, and plasma has been used as a sample source (8)(9)(10). The consistency of plasma composition makes it a good sample source for monitoring the CoV load.

CoV-enriched samples are critical for achieving a high detection rate. Current methods have a limited detection window, largely because they do not fully utilize the CoV viral RNA in the sample. Because of its high false-negative rate, the current method is unable to definitively rule out SARS within days after onset (11). An increase in viral RNA input could enhance the chance of detecting CoV (12).

The input to PCR can be increased by reducing the loss of CoV during sample preparation (8)(12) or by increasing the amount of prepared CoV RNA and cDNA product used in the final PCR amplification. A high input of CoV sample may increase the detection rate. Guided by this concept, we made the following modifications to a previously reported real-time quantitative RT-PCR for CoV (5): (a) instead of using a RNA capture column, we used Trizol to extract total RNA to increase the yield of CoV from samples; (b) instead of using 20–50% of the total obtained CoV RNA for the reverse transcription step, we dried the whole Trizol-extracted CoV RNA sample, dissolved it in the reverse transcription reaction mixture, and used it for the reverse transcription step; (c) instead of taking 10% of the reverse transcription product for PCR amplification, we used 50% of the reverse transcription product. In addition, to ensure efficient nested annealing of PCR primers, we performed reverse transcription with the CoV sequence-specific primer that extends 5 nucleotides beyond the PCR primer sequence. By making these modifications, we were able to achieve a detection rate of 80% as determined by testing of 116 samples from 44 SARS patients admitted to our hospital and diagnosed according to the WHO definition for SARS during the outbreak from March to June 2003. Among them, 28 were male and 16 were female, ages 10–74 years, with a mean age of 28 years. The patients were aware of and willing to participate in this test. For a more detailed description of the patients and methods, please see the Data Supplement that accompanies the online version of this Technical Brief at http://www.clinchem.org/content/vol50/issue7/. In addition, there were no false positives detected by our method, as assessed with samples from patients infected with other viruses. Furthermore, when plasma from a SARS patient was tested four times, it yielded a mean of CoV load of 3185 copies/0.2 mL of plasma with a an interassay CV of 10%.

Our main goal in establishing this method was to monitor CoV load during the clinical course. We first examined the CoV load in 44 SARS patients at different SARS stages, classified into three groups: group 1, days 1–7 after fever onset (n = 17 patients); group 2, days 13–39 after fever onset (n = 18 patients); and group 3, days 79–91 after fever onset (n = 9 patients). The data (Fig. 1A ) indicated that the mean CoV copy number in patients during days 1–7 after fever onset (group 1) was 8951/0.2 mL of plasma and that 15 of 17 (88%) patients had a CoV load substantially >100 copies, which could be easily detected by our modified method. In patients beyond 13 days after onset (groups 2 and 3), the mean CoV copy number decreased dramatically, to ∼550 in 0.2 mL of plasma. These data imply the following. (a) The peak shedding of CoV corresponds to the peak course of SARS, when the virus has the highest transmission potential, consistent with the epidemiologic data. (b) The residual SARS CoV may persist in a patient’s circulation for a relatively long time without obvious effects on the host. The pathophysiologic significance of a detectable residual CoV load lasting up to 2–3 months is not clear, and attention should be paid to this phenomenon. (c) In the development of SARS tests, it is important to take into account the timing of sample collection in the evaluation of the sensitivity and detection rate. (d) Finally, if a procedure cannot detect abundant CoV in the first-week sample, then it is unlikely to be effective for early diagnosis, monitoring of the therapeutic effect, or detecting subclinical SARS CoV infection. Our improved method can detect the presence of a few copies of CoV and has a high detection rate for first-week samples. Notably, the number of CoV copies detected in acute-phase patients (days 1–7 after fever onset) by our method is much higher than the values reported elsewhere (9). This may attributable to differences in the severity of patients’ infections and to differences in sample input at three steps: CoV mRNA extraction, CoV cDNA production, and PCR amplification. A small difference in sample input at each step could lead to a large difference in the final CoV copy number because of amplification of enzyme reactions.

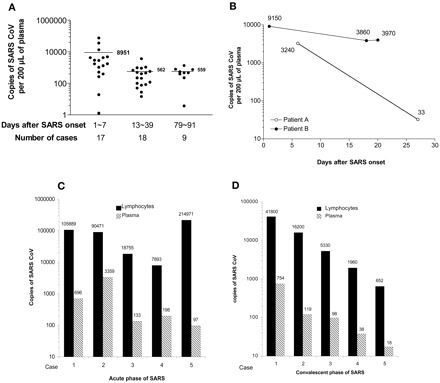

Figure 1.

CoV load in plasma samples from 44 patients in different phases of SARS infection (A); plasma viral loads in two individual SARS patients over the course of the disease (B); and comparison of CoV in 1 × 106 lymphocytes and 0.2 mL of plasma from five patients during days 1–7 after fever onset (C) or five patients during recovery (D).

(A), we obtained 200 μL of plasma from each of 44 SARS patients at different phases of the disease, extracted the RNA, and subjected it to real-time RT-PCR to determine the number of SARS CoV copies. The mean (SD) copy numbers were 8951 (19 393), 562 (842), and 559 (386) copies of CoV for days 1–7, days 13–36, and days 79–91 after fever onset, respectively. The horizontal bar indicates the mean copy number for each sample. The differences between time after onset of disease were significant: P <0.004 for days 1–7 vs days 13–36; P <0.035 for days 1–7 vs days 79–91; and P <0.42 for days 13–36 vs days 79–91 (Mann-Whitney test). (B) CoV viral loads in plasma from SARS patients were determined during the patients’ hospitalization. The patterns were different. The viral concentrations in most of the patients decreased rapidly (see Patient A as an example), whereas in some patients the concentrations remained persistently high (see Patient B as an example). (C and D), CoV concentrations in 1 × 106 lymphocytes (▪) and 0.2 mL of plasma (▦) from each of five patients during days 1–7 after fever onset (C) or from five patients during recovery (D) were determined with our modified method. In each case, the CoV concentration in the lymphocytes was significantly higher than the concentration in plasma (P <0.001, t-test).

We next tested whether our improved method could be used to monitor changes in CoV load in individual SARS patients. The method could detect the CoV load during the SARS course, as demonstrated in Fig. 1B , representative data from the 44 patients tested. Whereas patient A had a sharp decrease in CoV titer, patient B maintained a high CoV titer, reflecting individual differences in SARS course. Such dynamic changes in CoV concentrations in a patient’s circulation provide guidance for therapeutic interventions, especially the adjustment of doses of prednisolone and ribavirin.

Another way to increase CoV sample input to enhance CoV detection is to use a sample that is originally enriched in CoV. Because the SARS CoV is an RNA virus, it targets cells and uses the cellular machinery to replicate itself. In addition to the epithelial cells lining the respiratory tract, which are targets of CoV, the lymphocytes are also highly likely to be targeted by CoV because lymphopenia occurs in almost all SARS patients (13)(14)(15). We therefore separated lymphocytes from 1 mL of blood with Ficoll, extracted the total RNA from 1 × 106 of the lymphocytes, and used the recovered RNA in our modified quantitative method for CoV. Although lymphocytes and plasma from 20 healthy individuals and 20 patients with influenza or other viral infections (e.g., mumps and rubella) had no detectable CoV, a high concentration of CoV was found in 1 × 106 lymphocytes from 5 patients tested 1–7 days after fever onset and 5 patients who were recovering from SARS, which was one to four orders of magnitude higher than the concentration measured in 0.2 mL of plasma from the same patients (Fig. 1 , C and D). This finding provides evidence that lymphocytes are a target or reservoir for SARS CoV and that they are a better sample source than plasma for detecting SARS CoV.

In conclusion, we believe that the use of lymphocytes, which are highly enriched in CoV, and of a standardized simple Ficoll separation make the proposed method suitable for detecting and monitoring SARS-CoV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Charles B. Underhill for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported mainly by the National Science Foundation of China (Grant 30340009). L.Z. and S.K. were supported in part by grants from the US Army Medical Research & Materiel Command (Grants DAMD17-00-1-0081 and DAMD17-01-1-0708), by the National Cancer Institute of the NIH (Grant CA71545), and by the Susan G. Komen Foundation. L.Z. was a recipient of a Visiting Scholar Award from the Key Laboratory of China Education Ministry on Cell Biology and Tumor Cell Engineering, Xiamen University (Fujian, People’s Republic of China).

Contributor Information

Haibin Wang, Email: haibin_wang@sohu.com.

Lurong Zhang, Email: Lurong_Zhang@urmc.rochester.edu.

References

- 1.Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, Zaki SR, Peret T, Emery S, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1953-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rota PA, Oberste MS, Monroe SS, Nix WA, Campagnoli R, Icenogle JP, et al. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science 2003;300:1394-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marra MA, Jones SJ, Astell CR, Holt RA, Brooks-Wilson A, Butterfield YS, et al. The Genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science 2003;300:1399-1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars/casedefinition.htm (accessed May 30, 2003).. [Google Scholar]

- 5. http://www.tib-molbiol.de/download/vr_SARS_Primer_279_07.pdf (accessed May 30, 2003).. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization Multicentre Collaborative Network for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Diagnosis. A multicentre collaboration to investigate the cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003;361:1730-1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC, Yee WK, Wang T, Chan-Yeung M, et al. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1977-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng EK, Ng PC, Hon KL, Cheng WT, Hung EC, Chan KC, et al. Serial analysis of the plasma concentration of SARS coronavirus RNA in pediatric patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Chem 2003;49:2085-2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng EK, Hui DS, Chan KC, Hung EC, Chiu RW, Lee N, et al. Quantitative analysis and prognostic implication of SARS coronavirus RNA in the plasma and serum of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Chem 2003;49:1976-1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant PR, Garson JA, Tedder RS, Chan PK, Tam JS, Sung JJ. Detection of SARS coronavirus in plasma by real-time RT-PCR. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2468-2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enserink M. SARS in China. The big question now: will it be back?. Science 2003;301:299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poon LL, Chan KH, Wong OK, Yam WC, Yuen KY, Guan Y, et al. Early diagnosis of SARS coronavirus infection by real time RT-PCR. J Clin Virol 2003;28:233-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panesar NS. Lymphopenia in SARS. Lancet 2003;361:1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong RS, Wu A, To KF, Lee N, Lam CW, Wong CK, et al. Haematological manifestations in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: retrospective analysis. BMJ 2003;326:1358-1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Wo J, Shao J, Zhu H, Wu N, Li M, et al. SARS-coronavirus replicates in mononuclear cells of peripheral blood (PBMCs) from SARS patients. J Clin Virol 2003;28:239-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.