Abstract

Background

Mumps is a vaccine preventable disease that typically presents with unilateral or bilateral parotitis. In February 2007, mumps re-emerged in university students in Nova Scotia. Despite highly sensitive methods for mumps virus detection, only 14% (298/2082) of cases during the peak of the outbreak were laboratory confirmed.

Objectives

Due to the low positivity rate, this study investigated whether infection with other viral pathogens caused mumps-like presentations during the outbreak.

Study design

148 buccal specimens from patients who presented with unilateral or bilateral parotitis but had negative laboratory tests for mumps virus were tested for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) by quantitative PCR and 21 different viral markers using the Luminex xTAG Respiratory Virus Panel (RVP). Companion sera to each buccal specimen were available for EBV and CMV serology to differentiate acute infection from reactivation.

Results

No correlation was observed since viral pathogens were detected in both the parotitis and non-parotitis groups.

Conclusion

Although there was co-circulation of other viral pathogens during the mumps outbreak, no difference was observed in the prevalence between patients who presented with or without parotitis. The low positivity rate for specimens submitted for mumps diagnostics was likely the result of increased Public Health messaging and physician inexperience in recognizing mumps infection, suggesting the clinical acumen for mumps diagnosis based solely on clinical presentation is low.

Keywords: Mumps virus, Mimickers, Nova Scotia, Parotitis, Clinical diagnosis

1. Background

Clinical mumps is defined as the acute onset of unilateral or bilateral tender, self-limiting swelling of the parotid or other salivary glands, lasting 2 or more days without other apparent cause. However, 15–20% of mumps infections can be asymptomatic and 50% are associated with non-specific or respiratory symptoms.15 In February 2007, mumps re-emerged in university students in Nova Scotia. During the height of the outbreak (February to July, 2007), our laboratory performed over 3410 PCR tests for mumps virus on approximately 2082 patients.6 Of these, 298 positive PCR results were obtained, yielding a positivity rate of 14.3% (298/2082).6 The low positivity rate highlights the difficulty with diagnosing mumps infection based solely on clinical presentation. However, the possibility that infection with other circulating viruses could mimic mumps has yet to be explored.

2. Objectives

In an attempt to explain the low positivity rate of RT-PCR testing, molecular methods were used to investigate whether other viral pathogens causing mumps-like presentations co-circulated in Nova Scotia during the mumps outbreak.

3. Study design

A small subset of specimens collected during the outbreak was used in this study. Total nucleic acids were extracted using the automated MagnaPure LC (Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ) from 148 buccal specimens collected from patients presenting with or without parotitis who tested negative for mumps by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and serology.6, 7 Specimens were tested for the presence of 17 respiratory viruses using the xTAG RVP test from Luminex Molecular Diagnostics (Toronto, Ontario) which detects influenza A and B, parainfluenza viruses 1–4 (PIV), respiratory syncytial virus A and B, adenovirus, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus/enterovirus (including Coxsackie viruses associated with parotitis), and coronaviruses OC43, 229E, NL63, HKU1 and SARS CoV.10 In addition, quantitative PCR was performed on the LightCycler 2.0 platform (Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ) to determine the presence of EBV and CMV using Artus EBV LightCycler (LC) PCR and Artus CMV LC PCR kits (Qiagen Inc., Mississauga, ON), respectively. To resolve whether the presence of EBV or CMV was due to reactivation rather than primary infection, companion sera submitted at the same time as the buccal specimen were tested for serologic evidence of acute infection. The study was approved by the Capital Health Research Ethics Board. All samples were collected previously and annonamized with no patient identifiers prior to testing.

4. Results

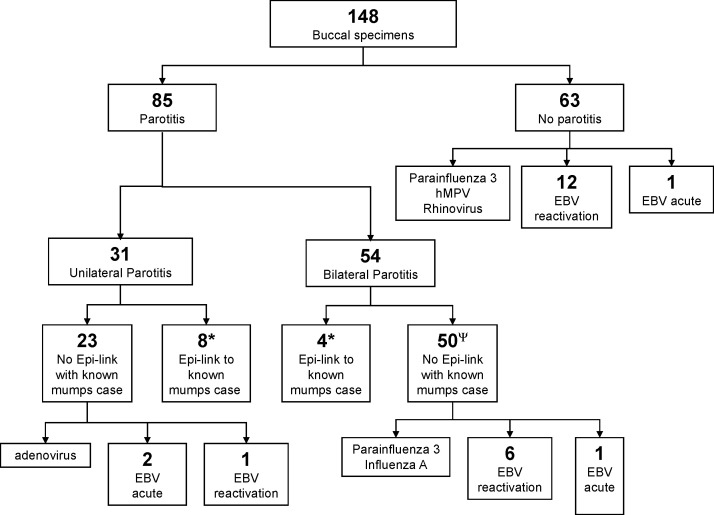

Of 148 specimens submitted from patients who were assessed by physicians to have possible mumps, only 85 were felt to have parotitis when assessed by Nova Scotia Public Health (Fig. 1 ). The median age of this group was 26 years (13–68 years) 65% of whom were female. The remaining 63 did not have evidence of parotitis and were used as a comparative group. The median age, age distribution and gender ratio was the same as the parotitis group (26 years (7–68 years), 65% female). Overall 7 different viruses were identified between the two groups. Parainfluenza 3, influenza A and EBV was detected in patients with bilateral parotitis, and adenovirus and EBV was identified in the unilateral parotitis group (Fig. 1). In the non-parotitis group, parainfluenza 3, hMPV, rhinovirus, and EBV were identified. No CMV was detected in any group.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of viruses in patients with and without parotitis who had negative RT-PCR for mumps virus. *Would be considered a case according to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) mumps case definition, ΨNova Scotia case definition included bilateral parotitis with or without epidemiological link as a “case” as such these individuals were classified by Nova Scotia Public Health as cases but not by PHAC definition, hMPV: human metapneumovirus. EBV: Epstein-Barr virus.

Of 23 specimens where EBV was detected (13 in the non-parotitis and 10 in the parotitis groups), companion sera was evaluated for serologic evidence of primary infection or reactivation. As defined by the presence of EBV viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgM and the absence of anti-EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA) IgG, 3 of 10 in the parotitis group and 1 of 13 in the non-parotitis group were found to be acute EBV infections. The remaining patients with detectable EBV all had anti-EBNA IgG suggesting viral shedding due to reactivation rather than primary disease. The average viral load for those with acute infection (7.02 log) was significantly higher (P < 0.005) than shedding due to reactivation (5.51 log).

5. Discussion

As part of outbreak management, the Nova Scotia Health Promotion and Protection (NSHPP) developed a case definition which differed slightly from the WHO definition. During the Nova Scotia outbreak, a person could be classified as a “confirmed” case of mumps in the absence of a positive laboratory test if they presented with bilateral parotitis (regardless of whether or not they had an epidemiologic linkage with a known case of mumps). This criterion was included since it was assumed that the likelihood of a pathogen other than mumps causing bilateral parotitis was low. However, other the possibility of other viral causes in this cohort has not been explored.

Although other viral pathogens were identified in this study, the number is small and they were distributed equally in both patients with and without parotitis suggesting there is no correlation. However, viral pathogens were identified in patients with bilateral parotitis suggesting that bilateral parotitis alone should not be used without laboratory confirmation for the diagnosis of mumps.

The literature implicating other viruses in mumps-like illness is relatively sparse.2, 9, 11 Reported cases include parotitis complicating acute EBV infection1, 8, 12 or influenza.2, 3 Recently, the aetiology of mumps-like illness in Finnish children was examined using serology.5 Using serologic testing on mumps-negative patients, a viral cause was identified in 84 of 601 cases with parotid swelling, including EBV, PIV, adenovirus, enterovirus, parvovirus and human herpes virus type 6 (HHV-6).5 There have been no studies to date that have used molecular methods such as PCR to systematically identify other viral pathogens from patients who present with parotitis during a mumps outbreak.

There are a number of limitations to this study. It is possible that patients presenting with mumps-like illness had other causes of facial swelling such as lymphadenitis or non-infectious causes such as parotid stones. Secondly, because nasopharyngeal swabs are the ideal specimens for the detection of respiratory viruses, suboptimal sampling with buccal specimens may have lead to an under estimation of the true prevalence of these viruses.4, 14 In addition, since the outbreak specimens were collected using standard viral transport media containing antibiotics, bacterial causes of parotitis could not be evaluated. It is also possible that other viruses not tested could have contributed to the clinical presentation of these patients.

In addition, some patients in this study could have truly had mumps but had falsely negative RT-PCR results. Although RT-PCR on buccal specimens is the best diagnostic test for mumps, the sensitivity of RT-PCR was only 79% during this outbreak.6 It is also possible that specimens were collected too late after the onset of symptoms to yield a positive RT-PCR result. However, the majority of specimens were submitted during the first few days of symptoms when viral shedding should be maximal.6

This is the first study that has used molecular methods to systematically identify other viral pathogens from patients who present with parotitis during a mumps outbreak. Although other viral pathogens were circulating during the mumps outbreak, we failed to show any correlation between parotitis and viral pathogens that could mimic the clinical presentation of mumps infection. The most likely explanation for the low positivity rate may simply be the result of increased Public Health messaging which in the UK has lead to increased rates of reporting by front line clinicians.13 In addition, because the majority of the patients in the Nova Scotia outbreak had one dose of a mumps containing vaccine, this partial immunity likely modified the clinical presentation of mumps infection including minimally enlarged salivary glands and lower viral shedding making laboratory confirmation difficult. While we cannot conclusively say that physicians were inexperienced as we have not directly surveyed them regarding their experiences, the very low prevalence of disease in the decade preceding this outbreak suggests that many physicians would not have seen a case of mumps in their careers. This possible inexperience in combination with possible atypical presentations and increased public health messaging, led to increased specimen submission on patients with non-specific symptoms. This reflects the difficulty in diagnosing mumps in a partially immunized population, a challenge faced by front line clinicians during this outbreak.

Acknowledgments

JBM and SC are inventors on a patent relating to the xTAG™ RVP test. TFH and JJL have no conflicts to declare. Funding for this project was through a grant from the Capital Health Research fund.

References

- 1.Andersson J., Sterner G. A 16-month-old boy with infectious mononucleosis, parotitis and Bell's palsy. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1985;74:629–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1985.tb11048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battle S., Laudenbach J., Maguire J.H. Influenza parotitis: a case from the 2004 to 2005 vaccine shortage. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333:215–217. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31803b92c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brill S.J., Gilfillan R.F. Acute parotitis associated with influenza type A. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:1391–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197706162962408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Covalciuc K.A., Webb K.H., Carlson C.A. Comparison of four clinical specimen types for detection of influenza A and B viruses by optical immunoassay (FLU OIA Test) and cell culture methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3971–3974. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3971-3974.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidkin I., Jokinen S., Paananen A., Leinikki P., Peltola H. Etiology of mumps-like illness in children and adolescents vaccinated for measles, mumps, and rubella. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:719–723. doi: 10.1086/427338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatchette TF, Davidson R, Clay S, Pettipas J, LeBlanc J, Sarwal S, Forward KR. Laboratory diagnosis of mumps in a partially immunized population: the Nova Scotia experience. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.LeBlanc J.J., Pettipas J., Davidson R.J., Tipples G.A., Hiebert J., Hatchette T.F. Detection of mumps RNA by real-time one-step reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) on the lightcycler platform. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:4049–4051. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01446-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee A.C., Lim W.L., So K.T. Epstein-Barr virus associated parotitis. J Paediatr Child Health. 1997;33:177–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1997.tb01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Litman N., Baum S.G. Mumps virus. In: Mandell G.L., Bennett J.E., Dolin R., editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 6th ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. pp. 2006–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahony J., Chong S., Merante F., Yaghoubian S., Sinha T., Lisle C., Janeczko R. Development of a respiratory virus panel test for detection of twenty human respiratory viruses by use of multiplex PCR and a fluid microbead-based assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(9):2965–2970. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02436-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McQuone S.J. Acute viral and bacterial infections of the salivary glands. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 1999;32:793–811. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mor R., Pitlik S., Dux S., Rosenfeld J.B. Parotitis and pancreatitis complicating infectious mononucleosis. Isr J Med Sci. 1982;18:709–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olowokure B., Clark L., Elliot A.J., Harding D., Fleming A. Mumps and the media: changes in the reporting of mumps in response to newspaper coverage. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:385–388. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.042598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmid M.L., Kudesia G., Wake S., Read R.C. Prospective comparative study of culture specimens and methods in diagnosing influenza in adults. BMJ. 1998;316:275. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7127.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO Global Status of mumps immunization and surveillance. Weekly Epidemiol Record. 2005;48:418–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]