1. Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the major cause of bronchiolitis, a common disease in the first months of life (Esposito et al., 2005, Lanari et al., 2002, Purcell and Fergie, 2004). Bronchiolitis is also associated with influenza and parainfluenza viruses, adenovirus, rhinoviruses, and enteroviruses (Bosis et al., 2005, Coiras et al., 2003, Legg et al., 2005). Although human metapneumovirus (hMPV) and human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63) have been identified and associated with a significant proportion of bronchiolitis over the last 3 years, no pathogen is recovered in a substantial proportion of cases (Bastien et al., 2005, Chiu et al., 2005, Esper et al., 2005, Principi et al., 2004, Principi et al., 2006).

While studying the epidemiology of viral respiratory infections in 2156 children (1190 males; mean age ± S.D., 3.39 ± 3.40 years) who attended the Emergency Department of Milan University's Institute of Pediatrics because of acute disease (58.2% respiratory tract infections, 12.9% gastrointestinal and intra-abdominal diseases, 5.1% fever of unknown origin, 4.5% seizures with or without fever, 4.7% exanthematious disease, 4.4% nephritic or nephrotic syndrome, 3.7% skin and soft tissue infections, 2.3% bone or joint infections, 1.7% coagulation disorders, 1.0% meningitis/encephalitis, 0.9% sepsis, and 0.6% conjunctivitis) during the winter seasons from 2002–2003 to 2004–2005, we detected human coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1) in the nasopharyngeal secretions of an Italian pre-term infant suffering from bronchiolitis. The case reported here was the only sample containing human coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1).

2. Case report

A 1.5-month-old premature male Italian infant was admitted to the Emergency Department of Milan University's Institute of Pediatrics in February 2005 with a 2-day history of poor feeding, rhinorrhea, cough, and dyspnea in the absence of fever. He had been spontaneously delivered after a premature membrane rupture at the gestational age of 33 weeks (birth weight 2670 g; Apgar score 9 at 1 min). At birth, he was asymptomatic and no respiratory support was required. He was hospitalised for 7 days before being sent home. He was mixed-fed from birth, and showed adequate growth. He had never left Italy, and none of his contacts had travelled abroad in the previous 6 months. The child's father had experienced an uncomplicated febrile upper respiratory tract infection starting the day before the child was admitted. Bronchiolitis was diagnosed on the basis of the findings of rhinorrhea, tachypnea, chest retractions, wheezing and bibasilar rales. Chest radiography showed hyperinflated lungs and an increased anteroposterior diameter in lateral view without any parenchymal abnormalities. A nasopharyngeal aspirate was tested for adenovirus, influenza virus types A and B, RSV types A and B, parainfluenza viruses types 1, 2, 3 and 4, rhinoviruses, human metapneumovirus, human coronavirus 229E human coronavirus OC43, human coranovirus NL63 and HCoV-HKU1 by real-time amplification assays at the Department of Virology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands (Bosis et al., 2005, Fouchier et al., 2004, Heim et al., 2003, Kares et al., 2004, Maertzdorf et al., 2004, van der Hoek et al., 2004, Woo et al., 2005a). Total nucleic acids were isolated using a MagnaPureLC Isolation Station (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany), and a universal internal control virus to monitor the process from isolation of the nucleic acids until their real-time detection (Niesters, 2002). The RNA was amplified in a single-tube, two-step reaction using Taqman reverse transcription reagents and a PCR core reagent kit (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk a/d IJssel, The Netherlands) in an ABI 7700 or ABI 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). A cultured virus was used as a positive control for each assay except in the case of HCoV-HKU1, for which a cloned construct was synthesised from published sequences of part of the nucleoprotein gene (Woo et al., 2005a). On the basis of proficiency testing data (Templeton et al., 2006), the estimated sensitivity of each assay was less than 500–1000 copies/mL.

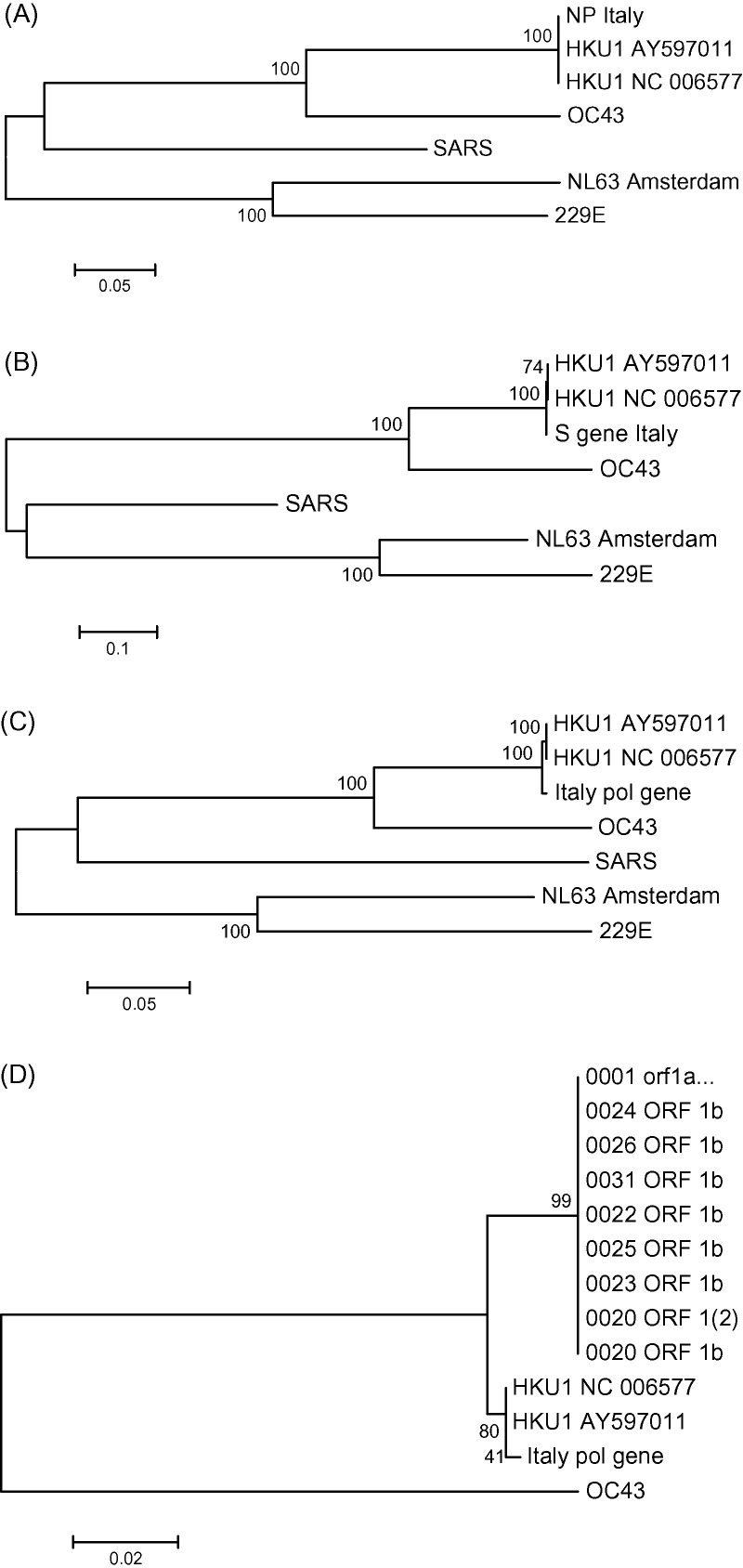

In the case of HCoV-HKU1, the NP gene (1326 bp), S gene (4441 bp) and part of the polymerase (ORF1B, 2815 bp) were amplified and sequenced using previously described primers (Woo et al., 2005c), and the sequence data analysed using a Sequence Navigator software sequencer (Applied Biosystems) and Seqman (DNASTAR, Madison, WI). The sequences were aligned using Clustal W (Bioedit 7.0.1). All of the available sequences of the corresponding gene sequences in Genbank were aligned, and their phylogenetic relations were calculated by means of bootstrapping resampling in order to calculate nodal confidence (n = 1000) using Kamura's two-parameter neighbour-joining method and MEGA 3.1. The data are shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

(A) Nucleoprotein gene (1326 bp) compared with the NP gene of other human coronaviruses. (B) Surface gene (4441 bp) compared with the S gene of other human coronaviruses. (C) Part of polymerase 1B (2815 bp) compared with other human coronaviruses. (D) Part of polymerase 1B (390 bp) compared with the Genbank submitted sequences of Woo et al. (2005a; NC_006577, AY597011) and Sloots et al. (2006; DQ190472 and DQ206693–DQ206699). The sequences of HCoV-229E (NC_002645), HCoV-OC43 (NC_005149), HCoV-NL63 (AY567487), HCoV-SARS (AY274119) and HCoV-HKU1 (NC_006577, AY597011) were obtained from Genbank.

Only one of 2156 aspirates was positive for HCoV-HKU1, and the low threshold cycle value (16) indicated a high viral load. Therapy consisted of oxygen supplementation, intravenous rehydration, and inhaled bronchodilators. The infant was discharged after 6 days and no respiratory recurrences were observed in the subsequent 6 months.

3. Discussion

HCoV-HKU1 is a coronavirus that has been detected in adults with pneumonia in China, and in small groups of children with respiratory or enteric infections in China, Australia, France and the United States (Esper et al., 2006, Lau et al., 2006, Sloots et al., 2006, Vabret et al., 2006, Woo et al., 2005a, Woo et al., 2005b, Woo et al., 2005c). Complete genome sequence analyses suggests that it originated from one major and some minor recombinations of group 2 coronaviruses (Woo et al., 2006). The Milan HCoV-HKU1 is closely related to the original viruses described by Woo et al., 2005a, Woo et al., 2005b, with minimal changes in the NP, S, and a large part of the polymerase 1B gene fragment. The smaller part of the polymerase 1B fragment discriminates the Milan virus more clearly from the others (Sloots et al., 2006, Woo et al., 2006), and has a closer relationship with the Hong Kong sequences and is distant from the Australian sequences.

Although the cause–effect relationship between HCoV-HKU1 and the disease of our patient could have only been confirmed by means of a respiratory tissue biopsy or serology on paired sera, it seems likely that this case of bronchiolitis was caused by HCoV-HKU1, which was present in large quantity. This is the second time that bronchiolitis has been associated with this virus, which has never been previously demonstrated in Southern Europe (Esper et al., 2006, Lau et al., 2006, Sloots et al., 2006, Vabret et al., 2006, Woo et al., 2005a, Woo et al., 2005b, Woo et al., 2005c).

Detecting HCoV-HKU1 in the nasopharyngeal secretions of a premature bronchiolitic infant confirms that HCoVs can cause moderate/severe respiratory infections (Fouchier et al., 2005, Kahn and McIntosh, 2005). As only a few patients with HCoV-HKU1 infection have been described so far, it is impossible to define the real importance of the virus. The fact that the majority of the reported cases (including ours) experienced a lower respiratory infection requiring hospitalisation suggests that its clinical impact may be significant. Previous studies have demonstrated that children aged less than 2 years are most at risk of HCoV-HKU1 infection, which significantly contributes to the microbial burden of patients with respiratory and enteric diseases during the colder months (Esper et al., 2006, Lau et al., 2006, Sloots et al., 2006, Vabret et al., 2006). HCoV-HKU1 can also be present as a persistent asymptomatic infection in patients with underlying conditions (Lau et al., 2006, Vabret et al., 2006). However, further epidemiological and clinical investigations are needed to precisely define the role of HCoV-HKU1 in respiratory infections.

References

- Bastien N., Robinson J.L., Tse A., Lee B.E., Hart L., Li Y. Human coronavirus NL-63 infections in children: a 1-year study. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4567–4573. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4567-4573.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosis S., Esposito S., Niesters H.G.M., Crovari P., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Principi N. Impact of human metapneumovirus in childhood: comparison with respiratory syncytial virus and influenza viruses. J Med Virol. 2005;75:101–104. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu S.S., Chan K.H., Chu K.W., Kwan S.W., Guan Y., Poon L.L.M. Human coronavirus NL63 infection and other coronavirus infections in children hospitalized with acute respiratory disease in Hong Kong, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1721–1729. doi: 10.1086/430301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coiras M.T., Pérez-Brena P., Garcìa M.L., Casas I. Simultaneous detection of influenza A, B, and C viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, and adenoviruses in clinical samples by multiplex reverse transcription nested-PCR assay. J Med Virol. 2003;69:132–144. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esper F., Weibel C., Ferguson D., Landry M.L., Kahn J.S. Evidence of a novel human coronavirus that is associated with respiratory tract disease in infants and young children. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:492–498. doi: 10.1086/428138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esper F., Weibel C., Ferguson D., Landry M.L., Kahn J.S. Coronavirus HKU1 infection in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:775–779. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.051316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito S., Gasparini R., Bosis S., Marchisio P., Tagliabue C., Tosi S. Clinical and socioeconomic impact of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection on healthy children and their households. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:933–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier R.A., Hartwig N.G., Bestebroer T.M., Niemeyer B., de Jong J.C., Simon J.H. A previously undescribed coronavirus associated with respiratory disease in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6212–6216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400762101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier R.A.M., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Kuiken T., Osterhaus A.D.M.E. Newer respiratory virus infections: human metapneumovirus, avian influenza virus, and human coronaviruses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:141–146. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000160903.56566.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim A., Ebnet C., Harste G., Pring-Akerblom P. Rapid and quantitative detection of human adenovirus DNA by real-time PCR. J Med Virol. 2003;70:228–239. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn J.S., McIntosh K. History and recent advances in coronavirus discovery. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;(24 Suppl):S223–S227. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000188166.17324.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kares S., Lonnrot M., Vuorinen P., Oikarinen S., Taurianen S., Hyoty H. Real-time PCR for rapid diagnosis of entero- and rhinovirus infections using LightCycler. J Clin Virol. 2004;29:99–104. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(03)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanari M. Prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus infection in Italian infants hospitalized for acute lower respiratory tract infections, and association between respiratory syncytial virus infection risk factors and disease severity. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;33:458–465. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Yip C.C., Tse H., Tsoi H.W., Cheng V.C. Coronavirus HKU1 and other coronavirus infections in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2063–2071. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02614-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legg J.P., Warner J.A., Johnston S., Warner J.O. Frequency of detection of picoronaviruses and seven other respiratory pathogens in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:611–616. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000168747.94999.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertzdorf J., Wang C.K., Brown J.B., Quinto J.D., Chu M., de Graaf M. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay for detection of human metapneumovirus from all known genetic lineages. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:981–986. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.981-986.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesters H.G. Clinical virology in real time. J Clin Virol. 2002;(25 Suppl 3):S3–S12. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Principi N., Bosis S., Esposito S. Human metapneumovirus infection in pediatric age. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:301–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Principi N., Esposito S., Bosis S. Human metapneumovirus in otherwise healthy infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1788–1790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell K., Fergie J. Driscoll Children's Hospital Respiratory Syncytial Virus Database Risk factors, treatment and hospital course in 3308 infants and young children, 1991 to 2002. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:418–423. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000126273.27123.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloots T.P., McErlean P., Speicher D.J., Arden K.E., Nissen M.D., Mackay I.M. Evidence of human coronavirus HKU1 and human bocavirus in Australian children. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templeton K.E., Forde C.B., Loon A.M., Claas E.C., Niesters H.G., Wallace P. A multi-centre pilot proficiency programme to assess the quality of molecular detection of respiratory viruses. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabret A., Dina J., Gouarin S., Petitjean J., Corbet S., Freymuth F. Detection of the new human coronavirus HKU1: a report of 6 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:634–639. doi: 10.1086/500136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoek L., Pyrc K., Jebbink M.F., Vermeulen-Oost W., Berkhout R.J., Wolthers K.C. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med. 2004;10:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nm1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P.C.Y., Lau S.K.P., Chu C., Tsoi H.W., Chan K.H., Yuen K.Y. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol. 2005;79:884–895. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.884-895.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P.C.Y., Lau S.K.P., Huang Y., Tsoi H.W., Chan K.H., Yuen K.Y. Phylogenetic and recombination analysis of coronavirus HKU1, a novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia. Arch Virol. 2005;150:2299–2311. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0573-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Tsoi H.W., Huang Y., Poon R.W., Chu C.M. Clinical and molecular epidemiological features of coronavirus HKU1-associated community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1898–1907. doi: 10.1086/497151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Yip C.C., Huang Y., Tsoi H.W., Chan K.H. Comparative analysis of 22 coronavirus HKU1 genomes reveals a novel genotype and evidence of natural recombination in coronavirus HKU1. J Virol. 2006;80:7136–7145. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00509-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]