Abstract

Background

Despite recent discovery of the novel human rhinovirus species, HRV-C, little is known about the association of HRV-C in diseases other than respiratory tract infections.

Objectives

To investigate the presence of HRV-C in fecal samples of children with gastroenteritis.

Study design

734 fecal samples from hospitalized children with gastroenteritis were subject to picornavirus detection by RT-PCR of the conserved 5′-NCR. Positive samples were subject to VP4 and 3Dpol gene analysis for species determination. The clinical and molecular epidemiology of HRV-C and other picornaviruses was analyzed.

Results

Picornaviruses were detected in 113 (15.4%) of 734 fecal samples from children with gastroenteritis by RT-PCR of 5′-NCR, with 58 containing potential HRVs and 55 containing other enteroviruses. PCR of the VP4 and 3Dpol regions was positive in 21 and 19 samples respectively (both regions positive in 8 samples). Sequencing analysis showed the presence of HRV-C in four samples, and diverse picornaviruses including HRV-A (n = 2), HEV-A (n = 2), HEV-B (n = 2), HEV-C (n = 21) and HPeV (n = 2) in other samples, with co-detection of HRV-C and HPeV in one sample. Of the four children with HRV-C detected in fecal samples, three presented with diarrhea in the absence of respiratory symptoms, while one also had acute bronchiolitis. The four HRV-C strains from fecal samples belonged to the existing clade of diverse HRV-C genotypes, indistinguishable from previous respiratory strains.

Conclusions

HRV-C can be detected in fecal samples of children with gastroenteritis, in the absence of respiratory symptoms. This study also represented the first to detect HPeV in our population.

Keywords: Human rhinovirus C, Gastroenteritis, Fecal, Stool, Children, Pediatric

1. Background

Although human rhinoviruses (HRVs) are the most frequent causes of respiratory tract infections, their impact on health is often ignored. Increasing reports have now implicated HRVs in more severe disease especially in children, elderly and immunocompromised patients.1, 2, 3 HRVs, which consist of more than 100 distinct serotypes, have been classified according to several parameters, including receptor specificity, antiviral susceptibility, and nucleotide sequence identities.4 Based on gene sequence analysis, all but one HRV serotypes were traditionally classified into two species, HRV-A and HRV-B.5, 6, 7

The severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in 2003 has boosted interest in the discovery of novel respiratory pathogens.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Recently, novel HRV genotypes have been discovered from respiratory specimens of patients from USA, Australia and Hong Kong.17, 18, 19, 20 Based on their distinct phylogenetic position and genome features from HRV-A and HRV-B,19, 21, 22, 23 these novel HRV genotypes have been proposed as a new HRV species, HRV-C, within the genus Enterovirus by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (http://talk.ictvonline.org/files/ictv_official_taxonomy_updates_since_the_8th_report/m/vertebrate-2008/1201.aspx). HRV-C has now been detected from patients with respiratory infections worldwide.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 We have also previously demonstrated HRV-C as important causes of hospitalizations due to respiratory illness in both adults and children.29 While other respiratory viruses such as human bocavirus (HBoV) have been associated with gastroenteritis,16, 30, 31 little is known about the association of HRV-C in diseases other than respiratory infections.

2. Objectives

In this study, we carried out a molecular epidemiology study to investigate the presence of HRV-C in fecal samples of children with gastroenteritis. Using consensus primers targeted to the conserved 5′-non-coding region (5′-NCR) of picornaviruses, we detected a diversity of human picornaviruses, including HRV-C. The clinical characteristics of children with HRV-C and other picornaviruses detected in fecal samples were also analyzed.

3. Study design

3.1. Patients and microbiological methods

All fecal specimens in this study were collected from hospitalized pediatric patients with gastroenteritis (age <18 years old) from two acute regional hospitals in Hong Kong from December 2004 to February 2005. Gastroenteritis was defined as the development of acute diarrhea with three or more loose stools per day. All fecal samples were tested for common bacterial diarrheal pathogens, rotavirus and HBoV as described previously.16 The clinical features, laboratory results and outcome of patients positive for picornaviruses were analyzed retrospectively.

3.2. RT-PCR for picornaviruses

Viral RNA was extracted using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). RT was performed using random hexamers and SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA).12, 32 PCR for human picornaviruses was performed using consensus primers, 5′-CTCCGGCCCCTGAATGYGGCTAA-3′ and 5′-GAAACACGGACACCCAAAGTAGT-3′, targeting the conserved 5′-NCR of common human picornaviruses as described previously.33 VP4 and 3D pol sequence analysis.

To determine the picornavirus species in positive fecal samples, the VP4 and 3Dpol regions were amplified and sequenced, using cDNA with modified published protocols.19, 32, 34 PCR for the VP4 region was performed using consensus primers described elsewhere.35 PCR for the 3Dpol region was performed using primers designed by multiple alignment of available 3Dpol sequences of human picornaviruses (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Primers used for amplification of 3Dpol region of HEV-A, HEV-B, HEV-C (PV), HEV-D, HPeV, HRV-A, HRV-B and HRV-C.

| Virus | Forward primer sequence (5′–3′) | Reverse primer sequence (5′–3′) | PCR product size |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEV-A | GTCTGGTTTAGAGCACTGGA | TCCTTGGTCCATCGAAT | 491 bp |

| HEV-B | GATTACCTGTGCAACTCCCA | GACATTAGCCCAGGTGACTT | 318 bp |

| HEV-C (PV) | TTTGCTTTTGACTACACAGG | CCTGATTGGGCTAGGAGACT | 353 bp |

| HEV-D | GTGAACGGTGGNATGCCNTC | GTAACTAGCAATNACRTCRTC | 159 bp |

| HPeV | ACCATGTGGTCTTCAATGAG | CAGTTTCTCTGGGTCTATTTC | 206 bp |

| HRV-A | ATATTATGAAGTNGARGGNGG | GTAAGAAAAGATNACRTCRTC | 169 bp |

| HRV-B | ATACAGTTGARGGNGGNATG | ACTATTAAGTCRTCNCCRTA | 157 bp |

| HRV-C | GAAGGNGGYATGCCMTCAGG | GCTAYCACATCATCMCCATA | 149 bp |

3.3. VP1 sequence analysis

To determine the genotype of human parechoviruses (HPeVs) detected in fecal samples, a partial fragment of the VP1 region was amplified and sequenced, using consensus primers, 5′-TCATGGGGBTCMCARATGG-3′ and 5′-GGTCCATCATCYTGDGCKGA-3′, designed by multiple alignment of available VP1 sequences of known HPeVs.

Both strands of all PCR products were sequenced twice using the PCR primers. Nucleotide sequences were compared to corresponding picornavirus sequences available in GenBank. Phylogenetic tree construction was performed using neighbor-joining method with GrowTree using Kimura's two-parameter correction, with bootstrap values calculated from 1000 trees (Genetics Computer Group, Inc.).

3.4. Nucleotide sequence accession number

The VP4 and 3Dpol nucleotide sequences of the HRV-C strains have been lodged within the GenBank sequence database under accession no. JN896368–JN896372.

4. Results

4.1. Detection of HRV-C and other picornaviruses in fecal samples from pediatric patients with acute gastroenteritis

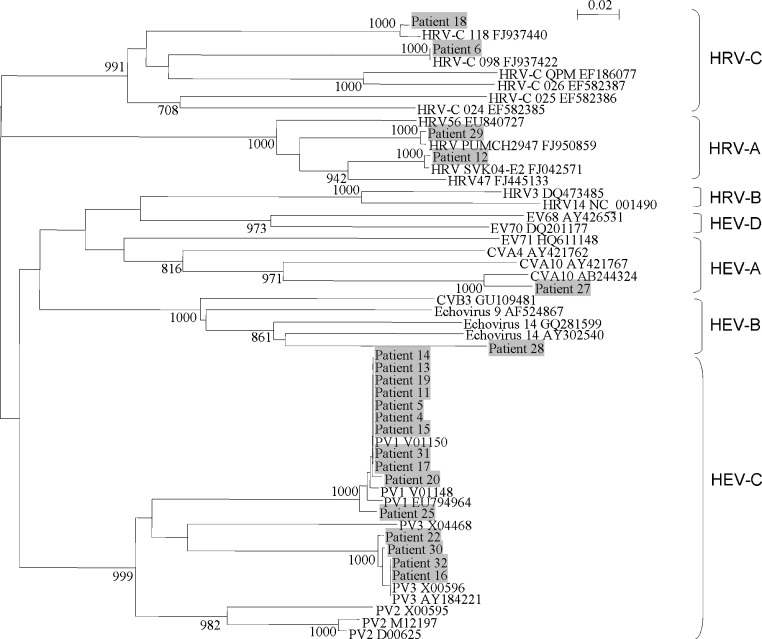

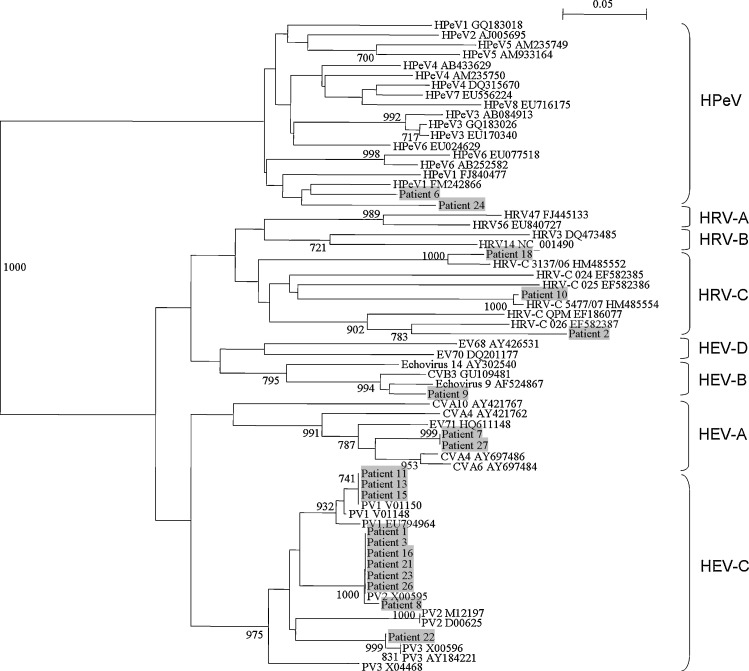

734 fecal samples [male:female = 1.7:1, age (mean ± SD) = 3.08 ± 4.62 years] from hospitalized pediatric patients with gastroenteritis were included. RT-PCR of 5′-NCR for picornaviruses was positive in 113 (15.4%) samples, among which 58 contained potential HRVs and 55 contained other human enteroviruses by sequence analysis (data not shown). To determine the picornavirus species in the positive samples, PCR of VP4 and 3Dpol regions was performed, which was positive in 32 samples (21 positive for VP4, 19 positive for 3Dpol and 8 positive for both regions) (Table 2 ). VP4 and 3Dpol sequence analysis showed that among the 32 samples, three contained HRV-C, two contained HRV-A, two contained HEV-A, two contained HEV-B, 21 contained HEV-C, one contained HPeV and one contained both HRV-C and HPeV (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 , Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the 32 children with picornaviruses detected in fecal samples.

| Patient no. | Sex | Age | Underlying disease | Diagnosis other than gastroenteritisa | Other pathogens identified from fecal samples | VP4 sequence analysis | 3Dpol sequence analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 2 mo | Prematurity, gastroschisis | None | None | − | PV2 |

| 2 | M | 2 mo | None | None | Salmonella group B | − | HRV-C |

| 3 | F | 3mo | None | None | None | − | PV2 |

| 4 | M | 6 day | Developmental delay | None | None | PV1 | − |

| 5 | M | 3 mo | Down syndrome, diaphragmatic paralysis, pneumonia | None | None | PV1 | − |

| 6 | M | 5 mo | None | None | None | HRV-C | HPeV |

| 7 | M | 8 mo | cleft lip | Acute bronchiolitis | HBoV | − | HEV-A |

| 8 | M | 2 mo | None | UTI | None | − | PV2 |

| 9 | M | 1 yr | None | None | None | − | HEV-B |

| 10 | M | 5 mo | None | Kawasaki disease | Rotavirus | − | HRV-C |

| 11 | M | 1 mo | None | None | None | PV1 | PV1 |

| 12 | M | 9 mo | Undescended testes, speech delay | URTIb | Rotavirus | HRV-A | − |

| 13 | M | 8 day | None | None | None | PV1 | PV1 |

| 14 | F | 6 day | None | Cow milk protein allergy | None | PV1 | − |

| 15 | M | 9 day | Antenatal hydronephrosis | Cow milk protein allergy | None | PV1 | PV1 |

| 16 | M | 3 mo | Congenital hydronephrosis, UTI | Antibiotic-related diarrhea | None | PV3 | PV2 |

| 17 | M | 28 day | Prematurity | Necrotizing enterocolitis | None | PV1 | − |

| 18 | M | 2 mo | None | Acute bronchiolitis | None | HRV-C | HRV-C |

| 19 | F | 1 mo | None | None | None | PV1 | − |

| 20 | M | 20 day | None | None | None | PV1 | − |

| 21 | M | 2 mo | None | None | None | − | PV2 |

| 22 | M | 7 mo | Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome | Parietal bone fracture | None | PV3 | PV3 |

| 23 | M | 3 mo | None | URTI | None | − | PV2 |

| 24 | M | 6 mo | Prematurity, lipomyelomeningocele | Post-operative fever | None | − | HPeV |

| 25 | M | 1 mo | None | None | None | PV1 | − |

| 26 | M | 2 mo | None | None | None | − | PV2 |

| 27 | M | 1 yr | Febrile convulsion | URTI | None | HEV-A | HEV-A |

| 28 | F | 7 yr | Chickenpox, physical abuse | Physical abuse | None | HEV-B | − |

| 29 | M | 3 mo | None | None | Salmonella group E | HRV-A | − |

| 30 | M | 3 mo | Hirshsprung's disease | Intestinal obstruction | None | PV3 | − |

| 31 | M | 26 day | None | None | None | PV1 | − |

| 32 | M | 4 mo | Cerebral palsy, epilepsy | None | None | PV3 | − |

UTI, urinary tract infection; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

Patient 12 also diagnosed to have influenza A H3N2 infection.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the complete VP4 region of 21 picornavirus strains detected from fecal samples of children. The trees were constructed by neighbor-joining method using Kimura's two-parameter correction and bootstrap values calculated from 1000 trees. 204 nucleotide positions in each VP4 region were included in the analysis. Strains detected in the present study are shaded. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 50 bases. The accession numbers of the previously published sequences are shown.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the partial 3Dpol region of 19 picornavirus strains detected from fecal samples of children. The trees were constructed by neighbor-joining method using Kimura's two-parameter correction and bootstrap values calculated from 1000 trees. 106 nucleotide positions in each 3Dpol region were included in the analysis. Strains detected in the present study are shaded. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 20 bases.

4.2. Clinical characteristics of patients with HRV-C and other picornaviruses detected in fecal samples

The clinical characteristics of the 32 patients with picornaviruses detected in fecal samples were summarized in Table 2. Diarrheal pathogens were also found in four samples, including Salmonella in two and rotavirus in two. HBoV was also detected in one sample.

Of the four patients with HRV-C detected in fecal samples, one (patient 18) also had acute bronchiolitis. Two patients had Salmonella group B (patient 2) and rotavirus (patient 10) detected in fecal samples respectively, with the latter also diagnosed to have Kawasaki disease. The other patient (patient 6) had HPeV co-detected. Although only VP4 sequence of HRV-C and 3Dpol sequence of HPeV was detected in this sample, it is likely that both viruses, instead of a HRV-C/HPeV recombinant virus, were present, since further sequencing of 5′-NCR using two sets of primers for HRV-C and HPeV respectively was positive for both viruses (data not shown). Of the two patients with HRV-A, one patient (patient 12) also had upper respiratory tract infection, with influenza A H3N2 detected in nasopharyngeal aspirate. This patient also had rotavirus co-detected in fecal sample. The other patient (patient 29) had Salmonella group E isolated from fecal sample.

The two patients with HEV-A had acute bronchiolitis (patient 7) and upper respiratory tract infection (patient 27) respectively, in addition to gastroenteritis. Patient 7 also had HBoV co-detected. Interestingly, the VP4 sequence from patient 27 was most closely related to human coxsackievirus A10 (CVA10), while the 3Dpol sequences from both patients were most closely related to CVA4, suggesting that the presence of a recombinant virus between CVA10 and CVA4 in patient 27. Both patients (patients 9 and 28) with HEV-B had symptoms limited to gastroenteritis. The VP4 sequence from patient 28 was most closely related to human echovirus 14, while the 3Dpol sequence from patient 9 was most closely related to human echovirus 9. Of the 21 patients with poliovirus (PV) (recently proposed to be reassigned under HEV-C), none presented with symptoms of poliomyelitis. These PV sequences likely represented remnants from oral PV vaccine. Sequence analysis of the VP4 and 3Dpol showed that 11 samples contained PV1, seven samples contained PV2 and four samples contained PV3, with one sample (from patient 16) contained both PV2 and PV3 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Table 2)

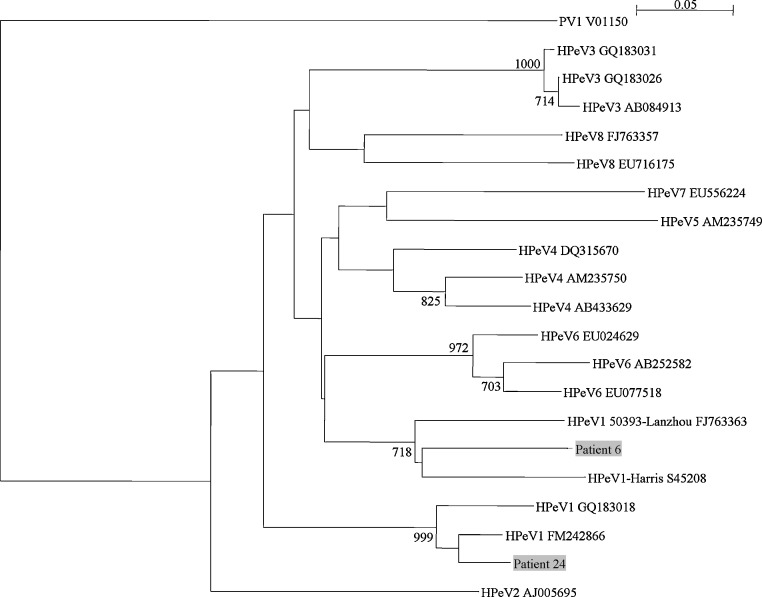

Both patients (patient 6 and 24) with HPeV had gastroenteritis without other localizing symptoms. Patient 6 also had HRV-C co-detected. Analysis of the partial VP1 sequences showed that both strains belonged to HPeV1, although they fell within each of two distinct clusters among existing HPeV1 strains (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the partial VP1 region of 2 HPeV strains detected from fecal samples of children. The trees were constructed by neighbor-joining method using Kimura's two-parameter correction and bootstrap values calculated from 1000 trees. 84 nucleotide positions in each VP1 region were included in the analysis. Strains detected in the present study are shaded. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 20 bases. Poliovirus 1 (PV1) was used as the outgroup.

5. Discussion

The present study represents the first to demonstrate that HRV-C may be associated with diseases other than respiratory infections. Although HRV-C has recently been found in the stool of two young children from Switzerland and Finland respectively, both patients had severe pneumonia and evidence of systemic infections. In the report from Switzerland, HRV-C was detected in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) specimen, pericardial fluid, plasma and stool of a 14-month-old child with pneumonia and pericarditis.36 The report from Finland described the detection of HRV-C in nasopharyngeal, bronchoalveolar lavage and bronchial specimens, stool and urine of a 3-week-old neonate with severe pneumonia and prolonged infection.37 Such fecal shedding of HRV-C therefore likely represented part of the disseminated viral infections with pneumonia.36, 37 In this study, three of the four children with HRV-C detected in fecal samples presented with diarrhea in the absence of respiratory symptoms, while the other also had acute bronchiolitis. As other potential diarrheal pathogens were also detected in the fecal samples from the former three children, the role of HRV-C in gastroenteritis remains to be determined. We have previously demonstrated HRV-C strains associated with respiratory infections as a clade of diverse genotypes that may easily evade immune protection.29 Analysis of VP4 sequences of the four HRV-C fecal strains showed that they belonged to the existing clade of diverse HRV-C genotypes, indistinguishable from respiratory strains (data not shown). This suggested that any HRV-C strain may be associated with respiratory or enteric disease. Moreover, HRV-C, as well as HRV-A, may possess similar biological properties as other enteroviruses, with the ability to replicate in gastrointestinal tract epithelium. Despite recent findings in ex vivo organ culture, HRV-C has not been successfully isolated in either airway or gastrointestinal cell lines.38 As a result, study of its tissue tropism and pathogenesis has been limited. Further studies are warranted to better understand the role and epidemiology of HRV-C in gastroenteritis and other diseases.

In this study, diverse picornaviruses were detected in a significant proportion (15.4%) of fecal samples from children with acute gastroenteritis by RT-PCR of the conserved 5′-NCR. The 5′-NCR was used for initial PCR screening for HRV-C because it is a highly conserved region and is well known to be much more sensitive than other genome regions for picornavirus detection. Although sequence analysis of the 5′-NCR suggested the presence of potential HRVs or other enteroviruses, further identification of the picornavirus species using VP4 and 3Dpol was only successful in 32 samples. The failure to amplify the VP4 and 3Dpol genes of picornaviruses in other samples may be due to the less conserved sequences than 5′-NCR or mutations in the primer regions. The 32 samples were shown to contain picornaivruses belonging to six different species, including 21 belonging to PV. The frequent detection of PV was not unexpected, as oral PV vaccine was routinely administered to our infants and PV was known to be isolated for up to 7 weeks after oral vaccination.39 Although picornaviruses, except HPeV, are not generally thought to be associated with gastroenteritis, many are transmitted by fecal–oral route and commonly isolated from stool. HRVs have also been occasionally detected in stool samples during search for viruses in other diseases, but detailed sequence analysis was lacking.40, 41 The present study showed that shedding of various picornaviruses, including HRVs, is common in children with gastroenteritis. Moreover, co-detection of different pathogens could be observed, similar to respiratory virus infections where co-infections are common.16, 42

The detection of a potential recombinant virus between CVA10 and CVA4, with incongruent clustering to CVA10 at VP4 and to CVA4 at 3Dpol, from patient 27 is intriguing. Mutation and recombination are well-known phenomena in the evolution of enteroviruses.43, 44, 45, 46 We have also recently described recombination in different picornaviruses, including “double-recombinant” EV71 strains which may represent an additional genotype D, as well as a recombinant CVA22 strain.32, 47 Complete genome sequencing of the present strain is required to confirm the suspected recombination events.

The present study represented the first to detect HPeV in our population, with two samples containing HPeV1. In a recent study on cerebrospinal fluid samples from the United Kingdom, HPeV3 was found to be the predominant picornavirus type in central nervous system-related infections in young children.48 In contrast, HPeV1 was found to be the most prevalent genotype among stool samples of children in both Japan and Thailand.49, 50 In another study from China, HPeV1 also accounted for 92.1% of stool samples of children positive for HPeV, although these HPeV1 strains shared only 75–82% amino acid identity with the prototype strain.51 The identification of our two HPeV strains as HPeV1 is in line with previous findings in Asian countries. Interestingly, the two strains each belonged to two distinct clades of HPeV1. Further studies may help delineate the genetic diversity of HPeV1 in our population and other countries.

Funding

This work is partly supported by the Research Grant Council Grant (HKU 768709M), University Grant Council; Strategic Research Theme Fund, and University Development Fund, The University of Hong Kong; and Consultancy Service for Enhancing Laboratory Surveillance of Emerging Infectious Disease for the HKSAR Department of Health.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

The use of patient samples in this study was approved by Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster under protocol no. UW 04-278 T/600.

Contributor Information

Susanna K.P. Lau, Email: skplau@hkucc.hku.hk.

Patrick C.Y. Woo, Email: pcywoo@hkucc.hku.hk.

References

- 1.Kaiser L., Aubert J.D., Pache J.C., Deffernez C., Rochat T., Garbino J. Chronic rhinoviral infection in lung transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1392–1399. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-489OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller E.K., Lu X., Erdman D.D., Poehling K.A., Zhu Y., Griffin M.R. Rhinovirus-associated hospitalizations in young children. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:773–781. doi: 10.1086/511821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner R.B., Rhinovirus: more than just a common cold virus. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:765–766. doi: 10.1086/511829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oberste M.S., Maher K., Kilpatrick D.R., Pallansch M.A. Molecular evolution of the human enteroviruses: correlation of serotype with VP1 sequence and application to picornavirus classification. J Virol. 1999;73:1941–1948. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1941-1948.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laine P., Savolainen C., Blomqvist S., Hovi T. Phylogenetic analysis of human rhinovirus capsid protein VP1 and 2A protease coding sequences confirms shared genus-like relationships with human enteroviruses. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:697–706. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80445-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledford R.M., Patel N.R., Demenczuk T.M., Watanyar A., Herbertz T., Collett M.S. VP1 sequencing of all human rhinovirus serotypes: insights into genus phylogeny and susceptibility to antiviral capsid-binding compounds. J Virol. 2004;78:3663–3674. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3663-3674.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savolainen C., Blomqvist S., Mulders M.N., Hovi T. Genetic clustering of all 102 human rhinovirus prototype strains: serotype 87 is close to human enterovirus 70. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:333–340. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-2-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fouchier R.A., Hartwig N.G., Bestebroer T.M., Niemeyer B., de Jong J.C., Simon J.H. A previously undescribed coronavirus associated with respiratory disease in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6212–6216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400762101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Hoek L., Pyrc K., Jebbink M.F., Vermeulen-Oost W., Berkhout R.J., Wolthers K.C. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med. 2004;10:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nm1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Yip C.C., Tse H., Tsoi H.W., Cheng V.C. Coronavirus HKU1 and other coronavirus infections in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2063–2071. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02614-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Chu C.M., Chan K.H., Tsoi H.W., Huang Y. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol. 2005;79:884–895. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.884-895.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Tsoi H.W., Huang Y., Poon R.W., Chu C.M. Clinical and molecular epidemiological features of coronavirus HKU1-associated community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1898–1907. doi: 10.1086/497151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sloots T.P., McErlean P., Speicher D.J., Arden K.E., Nissen M.D., Mackay I.M. Evidence of human coronavirus HKU1 and human bocavirus in Australian children. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allander T., Tammi M.T., Eriksson M., Bjerkner A., Tiveljung-Lindell A., Andersson B. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12891–12896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau S.K., Yip C.C., Que T.L., Lee R.A., Au-Yeung R.K., Zhou B. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of human bocavirus in respiratory and fecal samples from children in Hong Kong. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:986–993. doi: 10.1086/521310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamson D., Renwick N., Kapoor V., Liu Z., Palacios G., Ju J. MassTag polymerase-chain-reaction detection of respiratory pathogens, including a new rhinovirus genotype, that caused influenza-like illness in New York State during 2004–2005. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1398–1402. doi: 10.1086/508551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McErlean P., Shackelton L.A., Lambert S.B., Nissen M.D., Sloots T.P., Mackay I.M. Characterisation of a newly identified human rhinovirus, HRV-QPM, discovered in infants with bronchiolitis. J Clin Virol. 2007;39:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau S.K., Yip C.C., Tsoi H.W., Lee R.A., So L.Y., Lau Y.L. Clinical features and complete genome characterization of a distinct human rhinovirus (HRV) genetic cluster, probably representing a previously undetected HRV species, human rhinovirus-C, associated with acute respiratory illness in children. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3655–3664. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01254-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kistler A., Avila P.C., Rouskin S., Wang D., Ward T., Yagi S. Pan-viral screening of respiratory tract infections in adults with and without asthma reveals unexpected human coronavirus and human rhinovirus diversity. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:817–825. doi: 10.1086/520816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McErlean P., Shackelton L.A., Andrews E., Webster D.R., Lambert S.B., Nissen M.D. Distinguishing molecular features and clinical characteristics of a putative new rhinovirus species, human rhinovirus C (HRV C) PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmenberg A.C., Spiro D., Kuzmickas R., Wang S., Djikeng A., Rathe J.A. Sequencing and analyses of all known human rhinovirus genomes reveals structure and evolution. Science. 2009;324:55–59. doi: 10.1126/science.1165557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau S.K.P., Yip C.C.Y., Woo P.C.Y., Yuen K.Y. Human rhinovirus C: a newly discovered human rhinovirus species. Emerg Health Threats J. 2010;3:e2. doi: 10.3134/ehtj.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savolainen-Kopra C., Blomqvist S., Kilpi T., Roivainen M., Hovi T. Novel species of human rhinoviruses in acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:59–61. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318182c90a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dominguez S.R., Briese T., Palacios G. Multiplex MassTag-PCR for respiratory pathogens in pediatric nasopharyngeal washes negative by conventional diagnostic testing shows a high prevalence of viruses belonging to a newly recognized rhinovirus clade. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:219–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renwick N., Schweiger B., Kapoor V., Liu Z., Villari J., Bullmann R. A recently identified rhinovirus genotype is associated with severe respiratory-tract infection in children in Germany. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1754–1760. doi: 10.1086/524312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briese T., Renwick N., Venter M., Jarman R.G., Ghosh D., Köndgen S. Global distribution of novel rhinovirus genotype. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:944–947. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.080271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee W.M., Kiesner C., Pappas T., Lee I., Grindle K., Jartti T. A diverse group of previously unrecognized human rhinoviruses are common causes of respiratory illnesses in infants. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lau S.K.P., Yip C.C.Y., Lin A.W.C., Lee R.A., So L.Y., Lau Y.L. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of human rhinovirus C in children and adults in Hong Kong reveals a possible distinct human rhinovirus C subgroup. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1096–1103. doi: 10.1086/605697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vicente D., Cilla G., Montes M., Pérez-Yarza E.G., Pérez-Trallero E. Human bocavirus, a respiratory and enteric virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:636–637. doi: 10.3201/eid1304.061501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu J.M., Li D.D., Xu Z.Q., Cheng W.X., Zhang Q., Li H.Y. Human bocavirus infection in children hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis in China. J Clin Virol. 2008;42:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yip C.C., Lau S.K., Zhou B., Zhang M.X., Tsoi H.W., Chan K.H. Emergence of enterovirus 71 “double-recombinant” strains belonging to a novel genotype D originating from southern China: first evidence for combination of intratypic and intertypic recombination events in EV71. Arch Virol. 2010;155:1413–1424. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0722-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tapparel C., Cordey S., Van Belle S., Turin L., Lee W.M., Regamey N. New molecular detection tools adapted to emerging rhinoviruses and enteroviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1742–1749. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02339-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lau S.K.P., Woo P.C.Y., Lai K.K., Huang Y., Yip C.C.Y., Shek C.T. Complete genome analysis of three novel picornaviruses from diverse bat species. J Virol. 2011;85:8819–8828. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02364-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wisdom A., Leitch E.C., Gaunt E., Harvala H., Simmonds P. Screening respiratory samples for detection of human rhinoviruses (HRVs) and enteroviruses: comprehensive VP4-VP2 typing reveals high incidence and genetic diversity of HRV species C. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3958–3967. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00993-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tapparel C., L’Huillier A.G., Rougemont A.L., Beghetti M., Barazzone-Argiroffo C., Kaiser L. Pneumonia and pericarditis in a child with HRV-C infection: a case report. J Clin Virol. 2009;45:157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broberg E., Niemelä J., Lahti E., Hyypiä T., Ruuskanen O., Waris M. Human rhinovirus C – associated severe pneumonia in a neonate. J Clin Virol. 2011;51:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bochkov Y.A., Palmenberg A.C., Lee W.M., Rathe J.A., Amineva S.P., Sun X. Molecular modeling, organ culture and reverse genetics for a newly identified human rhinovirus C. Nat Med. 2011;17:627–632. doi: 10.1038/nm.2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Más Lago P., Gary H.E., Jr., Pérez L.S., Cáceres V., Olivera J.B., Puentes R.P. Poliovirus detection in wastewater and stools following an immunization campaign in Havana. Cuba Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:772–777. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Victoria J.G., Kapoor A., Li L., Blinkova O., Slikas B., Wang C. Metagenomic analyses of viruses in stool samples from children with acute flaccid paralysis. J Virol. 2009;83:4642–4651. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02301-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De W., Changwen K., Wei L., Monagin C., Jin Y., Cong M. A large outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by EV71 and CAV16 in Guangdong, China, 2009. Arch Virol. 2011;156:945–953. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-0929-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greer R.M., McErlean P., Arden K.E., Faux C.E., Nitsche A., Lambert S.B. Do rhinoviruses reduce the probability of viral co-detection during acute respiratory tract infections? J Clin Virol. 2009;45:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukashev A.N., Lashkevich V.A., Ivanova O.E., Koroleva G.A., Hinkkanen A.E., Ilonen J. Recombination in circulating enteroviruses. J Virol. 2003;77:10423–10431. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10423-10431.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirkegaard K., Baltimore D The mechanism of RNA recombination in poliovirus. Cell. 1986;47:433–443. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang S.C., Hsu Y.W., Wang H.C., Huang S.W., Kiang D., Tsai H.P. Appearance of intratypic recombination of enterovirus 71 in Taiwan from 2002 to 2005. Virus Res. 2008;131:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoke-Fun C., AbuBakar S. Phylogenetic evidence for inter-typic recombination in the emergence of human enterovirus 71 subgenotypes. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yip C.C.Y., Lau S.K.P., Woo P.C.Y., Chan K.H., Yuen K.Y. Complete genome sequence of a coxsackievirus A22 strain in Hong Kong reveals a natural intratypic recombination event. J Virol. 2011;85:12098–12099. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05944-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harvala H., McLeish N., Kondracka J., McIntyre C.L., McWilliam Leitch E.C., Templeton K. Comparison of human parechovirus and enterovirus detection frequencies in cerebrospinal fluid samples collected over a 5-year period in edinburgh: HPeV type 3 identified as the most common picornavirus type. J Med Virol. 2011;83:889–896. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ito M., Yamashita T., Tsuzuki H., Kabashima Y., Hasegawa A., Nagaya S. Detection of human parechoviruses from clinical stool samples in Aichi. Japan J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2683–2688. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00086-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pham N.T., Trinh Q.D., Khamrin P., Maneekarn N., Shimizu H., Okitsu S. Diversity of human parechoviruses isolated from stool samples collected from Thai children with acute gastroenteritis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:115–119. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01015-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhong H., Lin Y., Sun J., Su L., Cao L., Yang Y. Prevalence and genotypes of human parechovirus in stool samples from hospitalized children in Shanghai, China, 2008 and 2009. J Med Virol. 2011;83:1428–1434. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]