Abstract

Background

Human bocavirus (HBoV) was recently discovered in children with acute respiratory tract infections. We have included a PCR for HBoV in a study on airway infections in children.

Objectives

To study the occurrence of HBoV in Norwegian children, and to evaluate the results of a semiquantitive PCR.

Study design

During a 4-month period in the winter season 2006/2007 we collected nasopharyngeal aspirations from children who were admitted to the Department of Pediatrics. All samples were examined for 17 agents with real-time PCR.

Results

HBoV was detected in 45 of 376 samples (12%). The occurrence of HBoV was stable during the study period. Multiple viral infections were present in 78% of the samples (42% double, 20% triple and 16% quadruple infections). RS-virus, enterovirus and human metapneumovirus were the most frequently codetected agents. In samples with a high load for HBoV, significantly fewer multiple infections were found than in the other samples. Eighty-eight percent of the 25 patients with HBoV recorded as either the only or the dominating virus, and 50% of the other patients, had lower respiratory tract infection. The difference was statistically significant.

Conclusions

HBoV was frequently detected in nasopharyngeal aspirates from children with airway infections in Norway. Multiple viral infections were common among the HBoV-infected patients. Semiquantitive PCR results may be useful for interpretation of clinical relevance.

Keywords: Human bocavirus, Airway, Infection, Multiple, Children

1. Introduction

Human bocavirus (HBoV) was discovered in 2005 (Allander et al., 2005). It belongs to the family parvoviridae, and it is the second virus in this family to be associated with human disease (after parvovirus B19). Little is known about the virus’ kinetics and cell tropism.

HBoV is common in airway samples from children less than 5 years with respiratory tract infections, and it has a worldwide distribution (Allander et al., 2007, Arnold et al., 2006, Arden et al., 2006, Fry et al., 2007, Manning et al., 2006, Regamey et al., 2007). A causal relationship between HBoV and airway infection has not been established yet, but some controlled studies supporting this hypothesis have been published (Allander et al., 2007, Fry et al., 2007, Kesebir et al., 2006, Maggi et al., 2007, Manning et al., 2006).

We have studied the occurrence of HBoV in Norwegian children with respiratory tract infections, and evaluated the semiquantitative PCR-results against clinical manifestations.

2. Methods

We collected nasopharyngeal aspirates from children who were admitted to the Department of Pediatrics, St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital with respiratory tract infections during the time period November 13, 2006 to March 16, 2007. St. Olavs Hospital is the regional hospital for Mid-Norway covering a population of 640 000. Clinical data were obtained from medical records. The children were classified in two main diagnosis categories: lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) and upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). Other diagnoses not mentioned in the statistics included tonsillitis, gastroenteritis and fever. LRTI was diagnosed in the presence of dyspnea, signs of lower airway obstruction (wheezing, retractions) and/or a positive radiogram (infiltrates, atelectasis, air trapping). URTI was diagnosed when rhinitis, pharyngitis and/or otitis media was present in the absence of signs of LRTI.

Using PCR the nasopharyngeal aspirations were examined for adenovirus, HBoV, coronavirus (OC43, 229E and NL63), enterovirus, human metapneumovirus, influenza A and B virus, parainfluenza virus type 1-3, RS-virus, rhinovirus, Bordetella pertussis, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. All PCRs were real-time assays based on TaqMan probes. The target for the HBoV-PCR was the NP-1-gene. Selections of primers and probe were based the sequences published by Allander et al. (2005). (Forward primer: CCA CGT GAC GAA GAT GAG CTC, reverse primer TAG GTG GCT GAT TGG GTG TTC, probe CCG AGC CTC TCT CCC CAC TGT GTC G, 5′6-FAM, 3′ TAMRA.) The amount of virus in each sample was recorded semiquantitatively based on the C t-value (cycle threshold value) and grouped in three categories (high, medium and low viral load). The break points were set to C t 28 and C t 35. HBoV was recorded as the dominating virus in a sample when the C t-value was at least three cycles lower than the C t-value for any other virus.

In addition all samples were collected on ordinary virus transport media without antibiotics and cultured for viruses and bacteria with standard methods.

3. Results

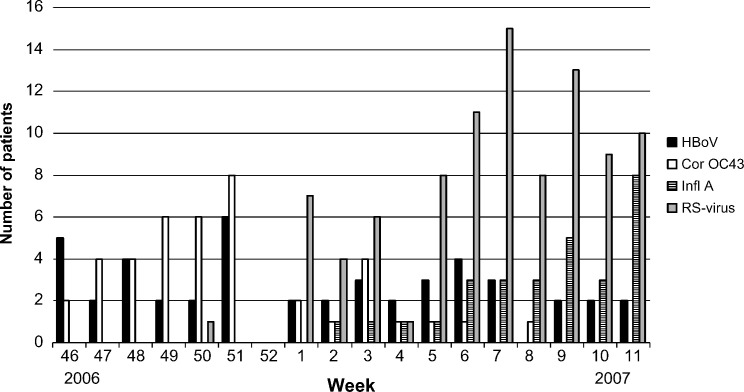

HBoV was detected in 45 of 376 nasopharyngeal aspirates (12%). It was the fourth most common virus in the material after RS-virus (25%), rhinovirus (17%) and human metapneumovirus (14%). Other common viruses in the material were enterovirus (11%) and coronavirus OC43 (11%). During the 4-month study period the occurrence of HBoV was stable, in contrast to coronavirus OC43, influenza A and RS-virus, which varied significantly (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Number of human bocavirus (HBoV), coronavirus OC43 (Cor OC43), influenza A-virus (Infl A) and RS-virus per week.

At least one virus was detected in 78% of the 376 samples in the total material. One solitary virus was found in 50%, two viruses in 21%, three viruses in 5% and four viruses in 2% of the samples.

Coinfections were detected in 78% of the 45 HBoV-positive samples. 42% of the samples contained one other virus, 20% contained two and 16% contained three other viruses. Table 1 shows the distribution of the codetected viruses. HBoV was more frequently detected in samples from patients with multiple infections. The proportion of samples containing HBoV increased with the number of viruses found per sample (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Number of codetected viruses in 35 HBoV-infected patients who had multiple viral infections

| Number of detections |

Part of triple/quadruple infections | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | PCR | Culture | ||

| Adenovirus | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Coronavirus OC43 | 10 | 10 | – | 6 |

| Coronavirus NL63 | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Enterovirus | 9 | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Human metapneumovirus | 7 | 7 | 1 | 4 |

| Influenza virus A | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Parainfluenzavirus type 3 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Rhinovirus | 10 | 10 | – | 8 |

| RS-virus | 8 | 8 | 7 | 3 |

| Cytomegalovirus | 2 | NDa | 2 | 1 |

The number of detections made by PCR and viral culture are shown. Right column: number of samples with at least two viruses detected in addition to HBoV.

Not done.

Table 2.

The eight most common viruses detected in 376 nasopharyngeal samples categorized after number of viruses detected per sample

| Total (n = 376) | Double infection (n = 77) | Triple infection (n = 19) | Quadruple infection (n = 7) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Adenovirus | 24 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 6 | 32 | 3 | 43 |

| Coronavirus OC43 | 41 | 11 | 18 | 23 | 6 | 32 | 4 | 57 |

| Enterovirus | 42 | 11 | 16 | 21 | 10 | 53 | 5 | 71 |

| HBoV | 45 | 12 | 19 | 25 | 9 | 47 | 7 | 100 |

| HMPV | 54 | 14 | 20 | 26 | 6 | 32 | 2 | 29 |

| Influenza A-virus | 29 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 16 | 1 | 14 |

| Rhinovirus | 65 | 17 | 19 | 25 | 8 | 42 | 4 | 57 |

| RSV | 93 | 25 | 29 | 38 | 6 | 32 | 1 | 14 |

Based on semi quantitative evaluation HBoV was found to be the dominating virus in 15 of the 35 patients with multiple viral infections (43%). In the samples with a high load for HBoV significantly fewer multiple infections were found (p < 0.001, Fisher's exact test) (Table 3 ). The same tendency was found for RS-virus, although not significant.

Table 3.

The HBoV-positive samples (n = 45) categorized after viral load and whether codetected viruses were present or not

| HBoV-load | HBoV only | Multiple infection | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | 9 | 13 | 22 |

| Medium/low | 1 | 22 | 23 |

Seventy-one percent of the HBoV-infected children had LRTI (bronchiolitis: 44% and pneumonia: 27%) and 20% had URTI. For the patients with HBoV recorded as either the dominating or the only virus the proportion of LRTI was 88%. In the group where HBoV was not the dominating agent the proportion was 50% (Table 4 ). The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.005, Fisher's exact test).

Table 4.

The HBoV-positive samples (n = 45) categorized after diagnosis group and whether HBoV was the dominating agent or not

| LRTI | URTI | Other | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBoV only/dominating virus | 22 (88)a | 1(4) | 2(8) | 25 |

| HBoV not dominating | 10 (50) | 8(40) | 2(10) | 20 |

Numbers in parentheses, percent.

The median age of the patients with HBoV-infection was 17 months. 58% were males.

Table 5 shows the results of the bacterial cultures. The bacteria were equally distributed in the diagnosis groups, and no association was found between viral and bacterial agents. For the majority of the patients who probably had a bacterial pneumonia, the bacterial culture was negative. These patients had received antibiotics before admission.

Table 5.

Results of bacterial cultures from the 45 samples containing HBoV

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| S. pneumoniae | 13 | 29 |

| H. influenzae | 8 | 18 |

| M. catharralis | 4 | 9 |

| Normal flora | 4 | 9 |

| Negative culture | 16 | 36 |

4. Discussion

We found HBoV in 12% of the samples, which is a high number compared to other hospital based studies on respiratory infections in children (Arden et al., 2006, Arnold et al., 2006, Kesebir et al., 2006).

No evidence for a seasonal appearance of HBoV was found in our material, but the study period was too short for any conclusions to be made. However, the period was long enough to show a clear seasonality for coronavirus OC43, RS-virus and influenza A-virus.

With newer highly sensitive PCR-based methods, the number of viral detections in airway samples has increased considerably. A striking finding is the high number of coinfections. This is a common finding in HBoV-infected patients (Allander et al., 2007, Manning et al., 2006). In our study 78% of the HBoV-infected children had multiple viral infections. Coronavirus OC43, rhinovirus, enterovirus and RS-virus were the most frequently codetected viruses. We could not find any association between detection of HBoV and other specific viruses. The proportion of multiple viral infections in HBoV-infected patients has varied between 35 and 83% in other studies (Allander et al., 2007, Choi et al., 2006, Foulongne et al., 2006, Fry et al., 2007).

HBoV-infections were more frequent when the number of coinfections was high. In the total material (n = 376) HBoV was detected in all seven samples containing four viruses, and in half of the samples containing three viruses. Similar figures were found for enterovirus, rhinovirus and coronavirus OC43. In contrast, this tendency was not demonstrable for RS-virus and influenza A-virus. Long-time shedding of HBoV, enterovirus, coronavirus OC43 and rhinovirus is a possible explanation. When a single sample can contain as many as four or more viruses it becomes difficult to evaluate the clinical significance of each virus. One way to solve this problem may be to quantify the individual viral nucleic acids. Quantitative analysis of nasopharyngeal aspirates is methodologically difficult because the quality of the specimens obtained varies from person to person depending on sampling technique and the condition of the patients’ nasal mucosa. An exact quantitation may consequently give misleading results. We have therefore chosen to do a semiquantitive analysis and roughly group the results in three categories. Our results indicate that this approach can be fruitful. In samples with a high load of HBoV few other viruses were detected. This indicates that assessment of viral load may be of clinical relevance, but a prospective study including clinical data and a control group is needed for this question to be fully addressed.

Most of the HBoV-infected children had LRTI. This is in accordance with other studies (Arnold et al., 2006, Manning et al., 2006). The proportion of pneumonias was relatively high (27%). This may be a coincidental finding as more than half of the pneumonia patients probably had bacterial pneumonia. We found a higher proportion of LRTI in the patients where HBoV was the only or the dominating virus, indicating a tendency to cause lower respiratory tract infections.

The median age of 17 months is higher than the typical median age for RS-virus and human metapneumovirus (Døllner et al., 2004). Whether this is a result of differences in epidemiology or in virus kinetics remains to be elucidated. It is not known for how long time the virus can be detected in airway specimens. Allander et al. (2007) found HBoV in 19% of blood samples three weeks after an acute infection indicating that viremia can persist for some time after an acute infection.

Serum, urine and feces were also collected from some of the HBoV-positive patients. This was not done systematically, and many patients were discharged before the samples could be obtained. We detected HBoV in serum from four patients, all of whom had a high viral load. HBoV was detected in urine from two of these patients. This indicates that HBoV gives a viremia during acute infection and that shedding through urine can happen. HBoV was found in feces from two patients. One of them had gastroenteritis. In the fecal sample from this patient rotavirus was also detected giving a probable explanation for the gastroenteritis. In a recent study HBoV was proposed as a cause of gastroenteritis (Vicente et al., 2007). We therefore examined 101 fecal samples from unselected patients of all age groups with gastroenteritis. Only one specimen was positive for HBoV. This was a 1-year-old boy who also tested positive for rotavirus. Furthermore, he had a respiratory illness four weeks before the gastroenteritis. Thus, our data do not support the hypothesis that HBoV can cause gastroenteritis.

Our results indicate that semiquantitative recording of HBoV-PCR-results have clinical relevance. We have recently started a prospective study including a control group to explore this issue further.

References

- Allander T., Tammi M.T., Eriksson M., Bjerkner A., Tiveljung-Lindell A., Andersson B. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12892–12896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allander T., Jartti T., Gupta S., Niesters H.G.M., Lehtinen P., Österback R. Human bocavirus and acute wheezing in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:904–910. doi: 10.1086/512196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arden E.A., McErlean P., Nissen M.D., Sloots T.P., Mackay I.M. Frequent detection of human rhinoviruses, paramyxoviruses, coronaviruses and bocavirus during acute respiratory tract infections. J Med Virol. 2006;78:1232–1240. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold J.C., Singh K.K., Spector S.A., Sawyer M.H. Human bocavirus: Prevalence and clinical spectrum at a children's hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:283–288. doi: 10.1086/505399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi E.H., Lee H.J., Kim S.J., Eun B.W., Kim N.H., Lee J.A. The association of newly identified respiratory viruses with lower respiratory tract infections in Korean children, 2000–2005. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:585–592. doi: 10.1086/506350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Døllner H., Risnes K., Radtke A., Nordbø S.A. Outbreak of human metapneumovirus infection in Norwegian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:436–440. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000126401.21779.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulongne V., Olejnik Y., Perez V., Elaerts S., Rodiere M., Segondy M. Human bocavirus in French children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1251–1253. doi: 10.3201/eid1208.060213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry A.M., Lu X., Chittaganpitch M., Peret T., Fisher J., Dowell S.F. Human bocavirus: A novel parvovirus epidemiologically associated with pneumonia requiring hospitalization in Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1038–1045. doi: 10.1086/512163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesebir D., Vazquez M., Weibel C., Shapiro E.D., Ferguson D., Landry M.L. Human bocavirus infection in young children in the United States: Molecular epidemiological profile and clinical characteristics of a newly emerging respiratory virus. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1276–1282. doi: 10.1086/508213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi F., Andreoli E., Pifferi M., Meschi S., Rocchi J., Bendinelli M. Human bocavirus in Italian patients with respiratory diseases. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning A., Russel V., Eastick K., Leadbetter G.H., Hallam N., Templeton K. Epidemiological profile and clinical associations of human bocavirus and other human parvoviruses. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1283–1290. doi: 10.1086/508219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regamey N., Frey U., Deffernez C., Latzin P., Kaiser L. Isolation of human bocavirus from Swiss infants with respiratory infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:177–179. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000250623.43107.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente D., Cilla G., Montes M., Péres-Yarza E.G., Péres-Trallero E. Human bocavirus, a respiratory and enteric virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:636–637. doi: 10.3201/eid1304.061501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]