Abstract

Background

Human bocavirus (HBoV) is a newly discovered human parvovirus. HBoV was detected in respiratory samples by PCR, but its aetiologic role in the pathogenesis of acute respiratory infectious diseases is still unclear.

Results

In this report, we describe an atopic child affected by pneumonia, with a past history of wheezing. A panel of bacteria and respiratory viruses were searched in the nasopharyngeal swab, only human bocavirus was detected by PCR.

Conclusions

Detection of HboV, as the only microbial agent, in samples from children with wheezing and acute respiratory diseases supports the assumption that this emerging virus could have an aetiologic role in the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases.

Keywords: Bocavirus, Pneumonia

1. Introduction

Screening of most of the known respiratory viruses by PCR has allowed us to diagnose many viral infections in the majority of individuals with respiratory illnesses. However, many respiratory infections still remain undiagnosed. A new parvovirus, the human bocavirus (HBoV), has recently been discovered by the application of random PCR/cloning technique on respiratory samples (Allender et al., 2005). HBoV is suspected to be an etiologic agent of respiratory disease in humans (Manning et al., 2006, Maggi et al., 2007, Kesebir et al., 2007). Respiratory distress and abnormal radiographic chest findings have frequently been associated with HBoV. However, its causative role is still unclear. Most viruses have been identified by animal experiments or virus replication in tissue culture, but this virus was discovered by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples and it has not yet been grown in cell culture. Although, Koch's postulates have provided a standard for establishing a causal link between a pathogen and disease, in this case it was not possible to apply these rules. However, the frequent association of HBoV infection with respiratory tract disease (Anderson, 2007, Schenk et al., 2007, Simon et al., 2007) led us to consider this virus as a causative agent for respiratory tract diseases. Some studies have shown that HBoV is distributed all over the world (Manning et al., 2006, Maggi et al., 2007, Simon et al., 2007, Ma et al., 2006, Bastien et al., 2007) and recent data have shown that it can also be detected in stool samples from children with gastroenteritis (Vicente et al., 2007). Like other viruses, it is possible that HBoV could be involved in both respiratory and enteric diseases.

2. Results

In this report, we describe a case of pneumonia and severe wheezing associated with HBoV DNA in the pharyngeal swab sample from a child. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the child who provided specimens.

The child had been hospitalized at the age of 1 year due to rhinitis, airflow obstruction and acute wheezing. He was treated with corticosteroids and inhalative bronchodilatators to control bronchocostriction. No antibiotics were administered. No causative agent was found in nasopharyngeal swab or serological tests and no sign of chronic lung disease was present when he was released. During the following year, he frequently suffered from respiratory tract infections associated with bronchoconstriction. In order to understand the cause of bronchoconstriction, total and specific IgE were measured and high values were reported for egg proteins.

He was 3 years old when admitted for the most recent episode of respiratory distress. Clinical examination revealed a weakened general condition, a body temperature of 38 °C, tachycardia (pulse rate 140 per min), tachypnea (respiratory rate 52 per min), dyspnea, subcostal retractions, wheezing and left apical fine rales upon lung auscultation. Laboratory tests showed a leukocyte count of 22.0 × 109 l−1, and C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were normal. Chest radiography, interpreted by a paediatric radiologist, revealed hyperinflation and pneumonic infiltrates of the upper left lobe. Transcutaneously measured oxygen saturation was decreased to 82% while breathing ambient air and the patient required oxygen supplementation (8 l/min) and inhalative adrenaline. Oxygen was given for an additional 3 days along with intravenous corticosteroids and salbutamol by inhalation for persistent bronchoconstriction. The child improved and was dismissed from hospital after 7 days.

To assess the aetiology of this respiratory disease, blood and nasopharyngeal swab were drawn from the patient upon admission and tested for the presence of viral, bacterial and fungal pathogens. No infectious agent was detected by bacterial or fungal culture. The nasopharyngeal swab was also tested by PCR for Chamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis and Legionella pneumophila, respiratory syncytial virus (types A and B), metapneumovirus, influenza viruses (types A–C), parainfluenza viruses (PIV-1, PIV-2, PIV-3 and PIV-4), rhinovirus, enterovirus, adenovirus, coronavirus (HcoV-OC43, HcoV-229E, NL63 and HKU11) and human bocavirus. The only positive result was obtained for HBoV, using the primers described by Simon et al. (2007). Briefly, 5 μl of DNA (extracted from 200 μl of sample by using QIAamp mini kit; QIAGEN, Milan, Italy) was amplified using the forward primer 5′ CCCAAGAAACGTCGTCTAAC 3′ (HBoV nt 2301-2320) and the reverse primer 5′ GTGTTGACTGAATACAGTGT 3′ (HBoV nt 2681–2700), producing a fragment of 399 bp, partly overlapping the NP1 gene. The cycling conditions were: an initial step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94 °C for 40 s, 48 °C for 40 s and 72 °C for 1 min; and a final incubation at 72 °C for 5 min.

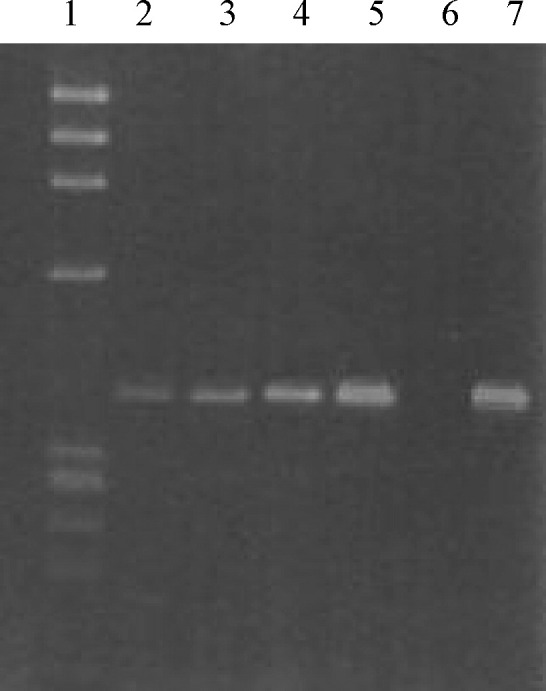

The sensitivity of this PCR was very high, detecting up to 10 copies of HBoV genome (Fig. 1 ). Virus detection was confirmed by sequence analysis of the PCR product. Another specimen drawn from the child one month after he was discharged from the hospital was negative for HBoV by PCR.

Fig. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of HboV PCR products. A plasmid (GC 302) was synthesized by cloning a 399 bp sequence of HboV (as described in Section 2) in TOPO (InVitrogen, Milan, Italy). This plasmid was diluted in order to load 10 (lane 2), 100 (lane 3), 1000 (lane 4) and 10,000 (lane 5) genome equivalents in each PCR and 1/5th of the volume was loaded on the gel as well as the amplified clinical sample (lane 7). Lane 1: DNA molecular weight standard (Φ × 174 digested with HaeIII); lane 6: negative control.

3. Discussion

The detection of HBoV in the nasopharyngeal swab in a child with a clinical picture of pneumonia supports the assumption that this virus has a causative role in respiratory diseases. The fact that it has been detected in children with or without respiratory symptoms could demonstrate that this virus might become more aggressive or overgrow, causing disease in particular hosts. Consequently, even the virus load could be an important parameter to be considered in the pathogenesis of the disease. We could not carry out a quantitative PCR due to the inadequacy of the sample and we did not have further samples from the child for a retrospective investigation. However, by a semi-quantitative assay, the sample had more than 105 genome equivalents per millilitre (Fig. 1).

In this case, it should be noted that the patient was suffering from wheezing and atopy characterized by a T cell driven airway inflammatory process, making the host an excellent substrate for viral growth. No coinfection was revealed, indicating that the presence of HBoV, the only agent in the sample, could not justify a pneumonia episode just as an innocent bystander. It is also possible that this virus, frequently detected in subjects with asthma or wheezing, could be reactivated by inflammatory processes and that this reactivation could cause severe respiratory diseases, particularly in children. This report is a further confirmation of other published data showing that HBoV could be a causative agent of lower respiratory infections in young children. Nevertheless, future studies are necessary to establish the pathological role of this virus in respiratory diseases.

References

- Allender T., Tammi M., Teriksson M., Bjerkner A., Tiveljung-Lindell A., Andersson B. Cloning of human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad USA. 2005;102:12891–12896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L.J. Human bocavirus: a new viral pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:911–912. doi: 10.1086/512438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien N., Chui N., Robinson J.L., Lee B.E., Dust K., Hart L. Detection of human bocavirus in Canadian children in a 1-year study. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:610–613. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01044-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesebir D., Vazquez M., Weibel C., Shapiro E.D., Ferguson D., Landry M.L. Human bocavirus infection in young children in the United States: molecular epidemiological profile and clinical characteristics of a newly emerging respiratory virus. J Infect Dis. 2007;194:1276–1282. doi: 10.1086/508213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning A., Russell V., Eastick K., Leadbetter G.H., Hallam N., Templeton K. Epidemiological profile and clinical associations of human bocavirus and other human bocavirus and other parvoviruses. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1283–1290. doi: 10.1086/508219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi F., Andreoli E., Pifferi M., Meschi S., Rocchi J., Bendinelli M. Human bocavirus in Italian patients with respiratory diseases. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Endo R., Ishiguro N., Ebihara T., Ishiko H., Ariga T. Detection of human bocavirus in Japanese children with lower respiratory tract infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1132–1134. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.1132-1134.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk T., Huck B., Forster J., Berner R., Neumann-Haefelin D., Falcone V. Human bocavirus DNA detected by quantitative real-time PCR in two children hospitalized for lower respiratory tract infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:147–149. doi: 10.1007/s10096-006-0244-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A., Groneck P., Kupfer B., Raiser R., Plum G., Tillmann R.-L. Detection of bocavirus DNA in nasopharyngeal aspirates of a child with bronchiolotis. J Infect. 2007;54:327–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente D., Cilla G., Montes M., Pérez-Yarza E., Pérez-Trallero E. Human bocavirus, a respiratory and enteric virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:636–637. doi: 10.3201/eid1304.061501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]