Abstract

Graph convolutional neural networks (GCNs) embed nodes in a graph into Euclidean space, which has been shown to incur a large distortion when embedding real-world graphs with scale-free or hierarchical structure. Hyperbolic geometry offers an exciting alternative, as it enables embeddings with much smaller distortion. However, extending GCNs to hyperbolic geometry presents several unique challenges because it is not clear how to define neural network operations, such as feature transformation and aggregation, in hyperbolic space. Furthermore, since input features are often Euclidean, it is unclear how to transform the features into hyperbolic embeddings with the right amount of curvature. Here we propose Hyperbolic Graph Convolutional Neural Network (HGCN), the first inductive hyperbolic GCN that leverages both the expressiveness of GCNs and hyperbolic geometry to learn inductive node representations for hierarchical and scale-free graphs. We derive GCNs operations in the hyperboloid model of hyperbolic space and map Euclidean input features to embeddings in hyperbolic spaces with different trainable curvature at each layer. Experiments demonstrate that HGCN learns embeddings that preserve hierarchical structure, and leads to improved performance when compared to Euclidean analogs, even with very low dimensional embeddings: compared to state-of-the-art GCNs, HGCN achieves an error reduction of up to 63.1% in ROC AUC for link prediction and of up to 47.5% in F1 score for node classification, also improving state-of-the art on the Pubmed dataset.

1. Introduction

Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (GCNs) are state-of-the-art models for representation learning in graphs, where nodes of the graph are embedded into points in Euclidean space [15, 21, 41, 45]. However, many real-world graphs, such as protein interaction networks and social networks, often exhibit scale-free or hierarchical structure [7, 50] and Euclidean embeddings, used by existing GCNs, have a high distortion when embedding such graphs [6, 32]. In particular, scale-free graphs have tree-like structure and in such graphs the graph volume, defined as the number of nodes within some radius to a center node, grows exponentially as a function of radius. However, the volume of balls in Euclidean space only grows polynomially with respect to the radius, which leads to high distortion embeddings [34, 35], while in hyperbolic space, this volume grows exponentially.

Hyperbolic geometry offers an exciting alternative as it enables embeddings with much smaller distortion when embedding scale-free and hierarchical graphs. However, current hyperbolic embedding techniques only account for the graph structure and do not leverage rich node features. For instance, Poincaré embeddings [29] capture the hyperbolic properties of real graphs by learning shallow embeddings with hyperbolic distance metric and Riemannian optimization. Compared to deep alternatives such as GCNs, shallow embeddings do not take into account features of nodes, lack scalability, and lack inductive capability. Furthermore, in practice, optimization in hyperbolic space is challenging.

While extending GCNs to hyperbolic geometry has the potential to lead to more faithful embeddings and accurate models, it also poses many hard challenges: (1) Input node features are usually Euclidean, and it is not clear how to optimally use them as inputs to hyperbolic neural networks; (2) It is not clear how to perform set aggregation, a key step in message passing, in hyperbolic space; And (3) one needs to choose hyperbolic spaces with the right curvature at every layer of the GCN.

Here we solve the above challenges and propose Hyperbolic Graph Convolutional Networks (HGCN)1, a class of graph representation learning models that combines the expressiveness of GCNs and hyperbolic geometry to learn improved representations for real-world hierarchical and scale-free graphs in inductive settings: (1) We derive the core operations of GCNs in the hyperboloid model of hyperbolic space to transform input features which lie in Euclidean space into hyperbolic embeddings; (2) We introduce a hyperbolic attention-based aggregation scheme that captures hierarchical structure of networks; (3) At different layers of HGCN we apply feature transformations in hyperbolic spaces of different trainable curvatures to learn low-distortion hyperbolic embeddings.

The transformation between different hyperbolic spaces at different layers allows HGCN to find the best geometry of hidden layers to achieve low distortion and high separation of class labels. Our approach jointly trains the weights for hyperbolic graph convolution operators, layer-wise curvatures and hyperbolic attention to learn inductive embeddings that reflect hierarchies in graphs.

Compared to Euclidean GCNs, HGCN offers improved expressiveness for hierarchical graph data. We demonstrate the efficacy of HGCN in link prediction and node classification tasks on a wide range of open graph datasets which exhibit different extent of hierarchical structure. Experiments show that HGCN significantly outperforms Euclidean-based state-of-the-art graph neural networks on scale-free graphs and reduces error from 11.5% up to 47.5% on node classification tasks and from 28.2% up to 63.1% on link prediction tasks. Furthermore, HGCN achieves new state-of-the-art results on the standard PUBMED benchmark. Finally, we analyze the notion of hierarchy learned by HGCN and show how the embedding geometry transforms from Euclidean features to hyperbolic embeddings.

2. Related Work

The problem of graph representation learning belongs to the field of geometric deep learning. There exist two major types of approaches: transductive shallow embeddings and inductive GCNs.

Transductive, shallow embeddings

The first type of approach attempts to optimize node embeddings as parameters by minimizing a reconstruction error. In other words, the mapping from nodes in a graph to embeddings is an embedding look-up. Examples include matrix factorization [3, 24] and random walk methods [12, 31]. Shallow embedding methods have also been developed in hyperbolic geometry [29, 30] for reconstructing trees [35] and graphs [5, 13, 22], or embedding text [39]. However, shallow (Euclidean and hyperbolic) embedding methods have three major downsides: (1) They fail to leverage rich node feature information, which can be crucial in tasks such as node classification. (2) These methods are transductive, and therefore cannot be used for inference on unseen graphs. And, (3) they scale poorly as the number of model parameters grows linearly with the number of nodes.

(Euclidean) Graph Neural Networks

Instead of learning shallow embeddings, an alternative approach is to learn a mapping from input graph structure as well as node features to embeddings, parameterized by neural networks [15, 21, 25, 41, 45, 47]. While various Graph Neural Network architectures resolve the disadvantages of shallow embeddings, they generally embed nodes into a Euclidean space, which leads to a large distortion when embedding real-world graphs with scale-free or hierarchical structure. Our work builds on GNNs and extends them to hyperbolic geometry.

Hyperbolic Neural Networks

Hyperbolic geometry has been applied to neural networks, to problems of computer vision or natural language processing [8, 14, 18, 38]. More recently, hyperbolic neural networks [10] were proposed, where core neural network operations are in hyperbolic space. In contrast to previous work, we derive the core neural network operations in a more stable model of hyperbolic space, and propose new operations for set aggregation, which enables HGCN to perform graph convolutions with attention in hyperbolic space with trainable curvature. After NeurIPS 2019 announced accepted papers, we also became aware of the concurrently developed HGNN model [26] for learning GNNs in hyperbolic space. The main difference with our work is how our HGCN defines the architecture for neighborhood aggregation and uses a learnable curvature. Additionally, while [26] demonstrates strong performance on graph classification tasks and provides an elegant extension to dynamic graph embeddings, we focus on link prediction and node classification.

3. Background

Problem setting

Without loss of generality we describe graph representation learning on a single graph. Let be a graph with vertex set and edge set , and let be d-dimensional input node features where 0 indicates the first layer. We use the superscript E to indicate that node features lie in a Euclidean space and use H to denote hyperbolic features. The goal in graph representation learning is to learn a mapping f which maps nodes to embedding vectors:

where . These embeddings should capture both structural and semantic information and can then be used as input for downstream tasks such as node classification and link prediction.

Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (GCNs)

Let denote a set of neighbors of , (Wℓ, bℓ) be weights and bias parameters for layer ℓ, and σ(·) be a non-linear activation function. General GCN message passing rule at layer ℓ for node i then consists of:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where aggregation weights wij can be computed using different mechanisms [15, 21, 41]. Message passing is then performed for multiple layers to propagate messages over network neighborhoods. Unlike shallow methods, GCNs leverage node features and can be applied to unseen nodes/graphs in inductive settings.

The hyperboloid model of hyperbolic space

We review basic concepts of hyperbolic geometry that serve as building blocks for HGCN. Hyperbolic geometry is a non-Euclidean geometry with a constant negative curvature, where curvature measures how a geometric object deviates from a flat plane (cf. [33] for an introduction to differential geometry). Here, we work with the hyperboloid model for its simplicity and its numerical stability [30]. We review results for any constant negative curvature, as this allows us to learn curvature as a model parameter, leading to more stable optimization (cf. Section 4.5 for more details).

Hyperboloid manifold

We first introduce our notation for the hyperboloid model of hyperbolic space. Let denote the Minkowski inner product,. We denote ℍd,K as the hyperboloid manifold in d dimensions with constant negative curvature −1/K (K > 0), and the (Euclidean) tangent space centered at point x

| (3) |

Now for v and w in , is a Riemannian metric tensor [33] and is a Riemannian manifold with negative curvature −1/K. is a local, first-order approximation of the hyperbolic manifold at x and the restriction of the Minkowski inner product to is positive definite. is useful to perform Euclidean operations undefined in hyperbolic space and we denote as the norm of .

Geodesics and induced distances

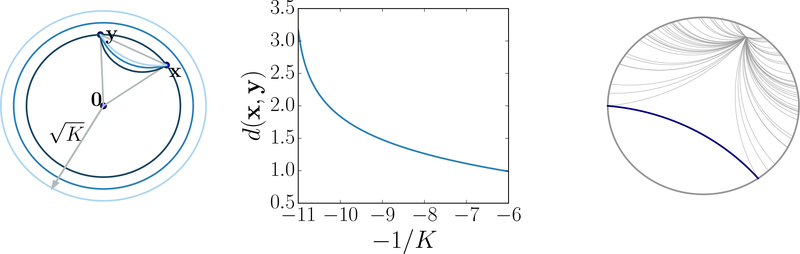

Next, we introduce the notion of geodesics and distances in manifolds, which are generalizations of shortest paths in graphs or straight lines in Euclidean geometry (Figure 1). Geodesics and distance functions are particularly important in graph embedding algorithms, as a common optimization objective is to minimize geodesic distances between connected nodes. Let x ∈ ℍd,K and , and assume that u is unit-speed, i.e. , then we have the following result:

Figure 1:

Left: Poincaré disk geodesics (shortest path) connecting x and y for different curvatures. As curvature (−1/K) decreases, the distance between x and y increases, and the geodesics lines get closer to the origin. Center: Hyperbolic distance vs curvature. Right: Poincaré geodesic lines. x

Proposition 3.1

Let x ∈ ℍd,K, be unit-speed. The unique unit-speed geodesic γx→u(·) such that γx→u (0) = x, is , and the intrinsic distance function between two points x, y in ℍd,K is then:

| (4) |

Exponential and logarithmic maps

Mapping between tangent space and hyperbolic space is done by exponential and logarithmic maps. Given x ∈ ℍd,K and a tangent vector , the exponential map assigns to v the point , where γ is the unique geodesic satisfying γ(0) = x and . The logarithmic map is the reverse map that maps back to the tangent space at x such that . In general Riemannian manifolds, these operations are only defined locally but in the hyperbolic space, they form a bijection between the hyperbolic space and the tangent space at a point. We have the following direct expressions of the exponential and the logarithmic maps, which allow us to perform operations on points on the hyperboloid manifold by mapping them to tangent spaces and vice-versa:

Proposition 3.2

For x ∈ ℍd,K, and y ∈ ℍd,K such that v ≠ 0 and y ≠ x, the exponential and logarithmic maps of the hyperboloid model are given by:

4. Hyperbolic Graph Convolutional Networks

Here we introduce HGCN, a generalization of inductive GCNs in hyperbolic geometry that benefits from the expressiveness of both graph neural networks and hyperbolic embeddings. First, since input features are often Euclidean, we derive a mapping from Euclidean features to hyperbolic space. Next, we derive two components of graph convolution: The analogs of Euclidean feature transformation and feature aggregation (Equations 1, 2) in the hyperboloid model. Finally, we introduce the HGCN algorithm with trainable curvature.

4.1. Mapping from Euclidean to hyperbolic spaces

HGCN first maps input features to the hyperboloid manifold via the exp map. Let x0,E ∈ ℝd denote input Euclidean features. For instance, these features could be produced by pre-trained Euclidean neural networks. Let denote the north pole (origin) in ℍd,K, which we use as a reference point to perform tangent space operations. We have 〈(0, x0,E), o〉 = 0. Therefore, we interpret (0, x0,E) as a point in and use Proposition 3.2 to map it to ℍd,K with:

| (5) |

4.2. Feature transform in hyperbolic space

The feature transform in Equation 1 is used in GCN to map the embedding space of one layer to the next layer embedding space and capture large neighborhood structures. We now want to learn transformations of points on the hyperboloid manifold. However, there is no notion of vector space structure in hyperbolic space. We build upon Hyperbolic Neural Network (HNN) [10] and derive transformations in the hyperboloid model. The main idea is to leverage the exp and log maps in Proposition 3.2 so that we can use the tangent space to perform Euclidean transformations.

Hyperboloid linear transform

Linear transformation requires multiplication of the embedding vector by a weight matrix, followed by bias translation. To compute matrix vector multiplication, we first use the logarithmic map to project hyperbolic points xH to . Thus the matrix representing the transform is defined on the tangent space, which is Euclidean and isomorphic to ℝd. We then project the vector in the tangent space back to the manifold using the exponential map. Let W be a d′ × d weight matrix. We define the hyperboloid matrix multiplication as:

| (6) |

where is on ℍd,K and maps to . In order to perform bias addition, we use a result from the HNN model and define b as an Euclidean vector located at . We then parallel transport b to the tangent space of the hyperbolic point of interest and map it to the manifold. If is the parallel transport from to (c.f. Appendix A for details), the hyperboloid bias addition is then defined as:

| (7) |

4.3. Neighborhood aggregation on the hyperboloid manifold

Aggregation (Equation 2) is a crucial step in GCNs as it captures neighborhood structures and features. Suppose that xi aggregates information from its neighbors with weights . Mean aggregation in Euclidean GCN computes the weighted average . An analog of mean aggregation in hyperbolic space is the Fréchet mean [9], which, however, has no closed form solution. Instead, we propose to perform aggregation in tangent spaces using hyperbolic attention.

Attention based aggregation

Attention in GCNs learns a notion of neighbors’ importance and aggregates neighbors’ messages according to their importance to the center node. However, attention on Euclidean embeddings does not take into account the hierarchical nature of many real-world networks. Thus, we further propose hyperbolic attention-based aggregation. Given hyperbolic embeddings , we first map and to the tangent space of the origin to compute attention weights wij with concatenation and Euclidean Multi-layer Percerptron (MLP). We then propose a hyperbolic aggregation to average nodes’ representations:

| (8) |

| (9) |

Note that our proposed aggregation is directly performed in the tangent space of each center point , as this is where the Euclidean approximation is best (cf. Figure 2). We show in our ablation experiments (cf. Table 2) that this local aggregation outperforms aggregation in tangent space at the origin (AGGo), due to the fact that relative distances have lower distortion in our approach.

Figure 2:

HGCN neighborhood aggregation (Eq. 9) first maps messages/embeddings to the tangent space, performs the aggregation in the tangent space, and then maps back to the hyperbolic space.

Table 2:

ROC AUC for link prediction on Airport and Disease datasets.

| Method | Disease | Airport |

|---|---|---|

| HGCN | 78.4 ± 0.3 | 91.8 ± 0.3 |

| HGCN-Atto | 80.9 ± 0.4 | 92.3 ± 0.3 |

| HGCN-Att | 82.0 ± 0.2 | 92.5 ± 0.2 |

| HGCN-C | 89.1 ± 0.2 | 94.9 ± 0.3 |

| HGCN-Att-C | 90.8 ± 0.3 | 96.4 ± 0.1 |

Non-linear activation with different curvatures

Analogous to Euclidean aggregation (Equation 2), HGCN uses a non-linear activation function, σ(·) such that σ(0) = 0, to learn non-linear transformations. Given hyperbolic curvatures −1/Kℓ−1, −1/Kℓ at layer ℓ − 1 and ℓ respectively, we introduce a hyperbolic non-linear activation with different curvatures. This step is crucial as it allows us to smoothly vary curvature at each layer. More concretely, HGCN applies the Euclidean non-linear activation in and then maps back to :

| (10) |

Note that in order to apply the exponential map, points must be located in the tangent space at the north pole. Fortunately, tangent spaces of the north pole are shared across hyperboloid manifolds of the same dimension that have different curvatures, making Equation 10 mathematically correct.

4.4. HGCN architecture

Having introduced all the building blocks of HGCN, we now summarize the model architecture. Given a graph and input Euclidean features , the first layer of HGCN maps from Euclidean to hyperbolic space as detailed in Section 4.1. HGCN then stacks multiple hyperbolic graph convolution layers. At each layer HGCN transforms and aggregates neighbour’s embeddings in the tangent space of the center node and projects the result to a hyperbolic space with different curvature. Hence the message passing in a HGCN layer is:

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

where −1/Kℓ − 1 and −1/Kℓ are the hyperbolic curvatures at layer ℓ − 1 and ℓ respectively. Hyperbolic embeddings at the last layer can then be used to predict node attributes or links.

For link prediction, we use the Fermi-Dirac decoder [23, 29], a generalization of sigmoid, to compute probability scores for edges:

| (14) |

where is the hyperbolic distance and r and t are hyper-parameters. We then train HGCN by minimizing the cross-entropy loss using negative sampling.

For node classification, we map the output of the last HGCN layer to the tangent space of the origin with the logarithmic map and then perform Euclidean multinomial logistic regression. Note that another possibility is to directly classify points on the hyperboloid manifold using the hyperbolic multinomial logistic loss [10]. This method performs similarly to Euclidean classification (cf. [10] for an empirical comparison). Finally, we also add a link prediction regularization objective in node classification tasks, to encourage embeddings at the last layer to preserve the graph structure.

4.5. Trainable curvature

We further analyze the effect of trainable curvatures in HGCN. Theorem 4.1 (proof in Appendix B) shows that assuming infinite precision, for the link prediction task, we can achieve the same performance for varying curvatures with an affine invariant decoder by scaling embeddings.

Theorem 4.1

For any hyperbolic curvatures −1/K, −1/K′ < 0, for any node embeddings H = {hi} ⊂ ℍd,K of a graph G, we find , , such that the reconstructed graph from H′ via the Fermi-Dirac decoder is the same as the reconstructed graph from H, with different decoder parameters (r, t) and (r′,t′).

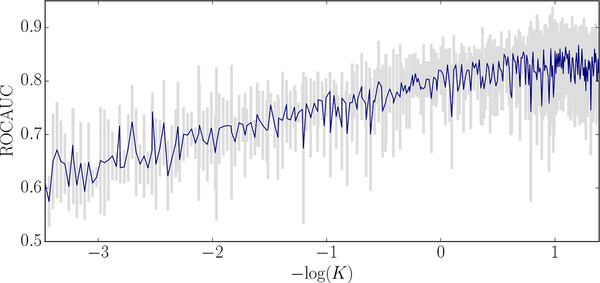

However, despite the same expressive power, adjusting curvature at every layer is important for good performance in practice due to factors of limited machine precision and normalization. First, with very low or very high curvatures, the scaling factor in Theorem 4.1 becomes close to 0 or very large, and limited machine precision results in large error due to rounding. This is supported by Figure 4 and Table 2 where adjusting and training curvature lead to significant performance gain. Second, the norms of hidden layers that achieve the same local minimum in training also vary by a factor of . In practice, however, optimization is much more stable when the values are normalized [16]. In the context of HGCN, trainable curvature provides a natural way to learn embeddings of the right scale at each layer, improving optimization. Figure 4 shows the effect of decreasing curvature (K = +∞ is the Euclidean case) on link prediction performance.

Figure 4:

Decreasing curvature (−1/K) improves link prediction performance on DISEASE.

5. Experiments

We comprehensively evaluate our method on a variety of networks, on both node classification (NC) and link prediction (LP) tasks, in transductive and inductive settings. We compare performance of HGCN against a variety of shallow and GNN-based baselines. We further use visualizations to investigate the expressiveness of HGCN in link prediction tasks, and also demonstrate its ability to learn embeddings that capture the hierarchical structure of many real-world networks.

5.1. Experimental setup

Datasets

We use a variety of open transductive and inductive datasets that we detail below (more details in Appendix). We compute Gromov’s δ−hyperbolicity [1, 28, 17], a notion from group theory that measures how tree-like a graph is. The lower δ, the more hyperbolic is the graph dataset, and δ = 0 for trees. We conjecture that HGCN works better on graphs with small δ-hyperbolicity.

Citation networks. Cora [36] and PubMed [27] are standard benchmarks describing citation networks where nodes represent scientific papers, edges are citations between them, and node labels are academic (sub)areas. CORA contains 2,708 machine learning papers divided into 7 classes while PUBMED has 19,717 publications in the area of medicine grouped in 3 classes.

Disease propagation tree. We simulate the SIR disease spreading model [2], where the label of a node is whether the node was infected or not. Based on the model, we build tree networks, where node features indicate the susceptibility to the disease. We build transductive and inductive variants of this dataset, namely DISEASE and DISEASE-M (which contains multiple tree components).

Protein-protein interactions (PPI) networks. PPI is a dataset of human PPI networks [37]. Each human tissue has a PPI network, and the dataset is a union of PPI networks for human tissues. Each protein has a label indicating the stem cell growth rate after 19 days [40], which we use for the node classification task. The 16-dimensional feature for each node represents the RNA expression levels of the corresponding proteins, and we perform log transform on the features.

Flight networks. Airport is a transductive dataset where nodes represent airports and edges represent the airline routes as from OpenFlights.org. Compared to previous compilations [49], our dataset has larger size (2,236 nodes). We also augment the graph with geographic information (longitude, latitude and altitude), and GDP of the country where the airport belongs to. We use the population of the country where the airport belongs to as the label for node classification.

Baselines

For shallow methods, we consider Euclidean embeddings (EUC) and Poincaré embeddings (HYP) [29]. We conjecture that HYP will outperform EUC on hierarchical graphs. For a fair comparison with HGCN which leverages node features, we also consider EUC-MIXED and HYP-MIXED baselines, where we concatenate the corresponding shallow embeddings with node features, followed by a MLP to predict node labels or links. For state-of-the-art Euclidean GNN models, we consider GCN [21], GraphSAGE (SAGE) [15], Graph Attention Networks (GAT) [41] and Simplified Graph Convolution (SGC) [44]2. We also consider feature-based approaches: MLP and its hyperbolic variant (HNN) [10], which does not utilize the graph structure.

Training

For all methods, we perform a hyper-parameter search on a validation set over initial learning rate, weight decay, dropout3, number of layers, and activation functions. We measure performance on the final test set over 10 random parameter initializations. For fairness, we also control the number of dimensions to be the same (16) for all methods. We optimize all models with Adam [19], except Poincaré embeddings which are optimized with RiemannianSGD [4, 48]. Further details can be found in Appendix. We open source our implementation4 of HGCN and baselines.

Evaluation metric

In transductive LP tasks, we randomly split edges into 85/5/10% for training, validation and test sets. For transductive NC, we use 70/15/15% splits for AIRPORT, 30/10/60% splits for DISEASE, and we use standard splits [21, 46] with 20 train examples per class for CORA and PUBMED. One of the main advantages of HGCN over related hyperbolic graph embedding is its inductive capability. For inductive tasks, the split is performed across graphs. All nodes/edges in training graphs are considered the training set, and the model is asked to predict node class or unseen links for test graphs. Following previous works, we evaluate link prediction by measuring area under the ROC curve on the test set and evaluate node classification by measuring F1 score, except for CORA and PUBMED, where we report accuracy as is standard in the literature.

5.2. Results

Table 1 reports the performance of HGCN in comparison to baseline methods. HGCN works best in inductive scenarios where both node features and network topology play an important role. The performance gain of HGCN with respect to Euclidean GNN models is correlated with graph hyperbolicity. HGCN achieves an average of 45.4% (LP) and 12.3% (NC) error reduction compared to the best deep baselines for graphs with high hyperbolicity (low δ), suggesting that GNNs can significantly benefit from hyperbolic geometry, especially in link prediction tasks. Furthermore, the performance gap between HGCN and HNN suggests that neighborhood aggregation has been effective in learning node representations in graphs. For example, in disease spread datasets, both Euclidean attention and hyperbolic geometry lead to significant improvement of HGCN over other baselines. This can be explained by the fact that in disease spread trees, parent nodes contaminate their children. HGCN can successfully model these asymmetric and hierarchical relationships with hyperbolic attention and improves performance over all baselines.

Table 1:

ROC AUC for Link Prediction (LP) and F1 score for Node Classification (NC) tasks. For inductive datasets, we only evaluate inductive methods since shallow methods cannot generalize to unseen nodes/graphs. We report graph hyperbolicity values δ (lower is more hyperbolic).

|

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset Hyperbolicity δ | Disease δ = 0 |

Disease-M δ = 0 |

Human PPI δ = 1 |

Airport δ = 1 |

PubMed δ = 3.5 |

Cora δ = 11 |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Method | LP | NC | LP | NC | LP | NC | LP | NC | LP | NC | LP | NC | |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Shallow | Euc | 59.8 ± 2.0 | 32.5 ± 1.1 | - | - | - | - | 92.0 ± 0.0 | 60.9 ± 3.4 | 83.3 ± 0.1 | 48.2 ± 0.7 | 82.5 ± 0.3 | 23.8 ± 0.7 |

| Hyp [29] | 63.5 ± 0.6 | 45.5 ± 3.3 | - | - | - | - | 94.5 ± 0.0 | 70.2 ± 0.1 | 87.5 ± 0.1 | 68.5 ± 0.3 | 87.6 ± 0.2 | 22.0 ± 1.5 | |

| Euc-Mixed | 49.6 ± 1.1 | 35.2 ± 3.4 | - | - | - | - | 91.5 ± 0.1 | 68.3 ± 2.3 | 86.0 ± 1.3 | 63.0 ± 0.3 | 84.4 ± 0.2 | 46.1 ± 0.4 | |

| Hyp-Mixed | 55.1 ± 1.3 | 56.9 ± 1.5 | - | - | - | - | 93.3 ± 0.0 | 69.6 ± 0.1 | 83.8 ± 0.3 | 73.9 ± 0.2 | 85.6 ± 0.5 | 45.9 ± 0.3 | |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| NN | MLP | 72.6 ± 0.6 | 28.8 ± 2.5 | 55.3 ± 0.5 | 55.9 ± 0.3 | 67.8 ± 0.2 | 55.3±0.4 | 89.8 ± 0.5 | 68.6 ± 0.6 | 84.1 ± 0.9 | 72.4 ± 0.2 | 83.1 ± 0.5 | 51.5 ± 1.0 |

| HNN[10] | 75.1 ± 0.3 | 41.0 ± 1.8 | 60.9 ± 0.4 | 56.2 ± 0.3 | 72.9 ± 0.3 | 59.3 ± 0.4 | 90.8 ± 0.2 | 80.5 ± 0.5 | 94.9 ± 0.1 | 69.8 ± 0.4 | 89.0 ± 0.1 | 54.6 ± 0.4 | |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| GNN | GCN[21] | 64.7 ±0.5 | 69.7 ± 0.4 | 66.0 ± 0.8 | 59.4 ± 3.4 | 77.0 ± 0.5 | 69.7 ± 0.3 | 89.3 ± 0.4 | 81.4 ± 0.6 | 91.1 ± 0.5 | 78.1 ± 0.2 | 90.4 ± 0.2 | 81.3 ± 0.3 |

| GAT [41] | 69.8 ±0.3 | 70.4 ± 0.4 | 69.5 ± 0.4 | 62.5 ± 0.7 | 76.8 ± 0.4 | 70.5 ± 0.4 | 90.5 ± 0.3 | 81.5 ± 0.3 | 91.2 ± 0.1 | 79.0 ± 0.3 | 93.7 ± 0.1 | 83.0 ± 0.7 | |

| SAGE [15] | 65.9 ± 0.3 | 69.1 ± 0.6 | 67.4 ± 0.5 | 61.3 ± 0.4 | 78.1 ± 0.6 | 69.1 ± 0.3 | 90.4 ± 0.5 | 82.1 ± 0.5 | 86.2 ± 1.0 | 77.4 ± 2.2 | 85.5 ± 0.6 | 77.9 ± 2.4 | |

| SGC [44] | 65.1 ± 0.2 | 69.5 ± 0.2 | 66.2 ± 0.2 | 60.5 ± 0.3 | 76.1 ± 0.2 | 71.3 ± 0.1 | 89.8 ± 0.3 | 80.6 ± 0.1 | 94.1 ± 0.0 | 78.9 ± 0.0 | 91.5 ± 0.1 | 81.0 ± 0.1 | |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Ours | HGCN | 90.8 ± 0.3 | 74.5 ± 0.9 | 78.1 ± 0.4 | 72.2 ± 0.5 | 84.5 ± 0.4 | 74.6 ± 0.3 | 96.4 ± 0.1 | 90.6 ± 0.2 | 96.3 ± 0.0 | 80.3 ± 0.3 | 92.9 ± 0.1 | 79.9 ± 0.2 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| (%) Err Red | −63.1% | −13.8% | −28.2% | −25.9% | −29.2% | −11.5% | −60.9% | −47.5% | −27.5% | −6.2% | +12.7% | +18.2% | |

|

|

|||||||||||||

On the Cora dataset with low hyperbolicity, HGCN does not outperform Euclidean GNNs, suggesting that Euclidean geometry is better for its underlying graph structure. However, for small dimensions, HGCN is still significantly more effective than GCN even with CORA. Figure 3c shows 2-dimensional HGCN and GCN embeddings trained with LP objective, where colors denote the label class. HGCN achieves much better label class separation.

Figure 3:

Visualization of embeddings for LP on DISEASE and NC on CORA (visualization on the Poincaré disk for HGCN). (a) GCN embeddings in first and last layers for DISEASE LP hardly capture hierarchy (depth indicated by color). (b) In contrast, HGCN preserves node hierarchies. (c) On CORA NC, HGCN leads to better class separation (indicated by different colors).

5.3. Analysis

Ablations

We further analyze the effect of proposed components in HGCN, namely hyperbolic attention (ATT) and trainable curvature (C) on AIRPORT and DISEASE datasets in Table 2. We observe that both attention and trainable curvature lead to performance gains over HGCN with fixed curvature and no attention. Furthermore, our attention model ATT outperforms ATTo (aggregation in tangent space at o), and we conjecture that this is because the local Euclidean average is a better approximation near the center point rather than near o. Finally, the addition of both ATT and C improves performance even further, suggesting that both components are important in HGCN.

Visualizations

We first visualize the GCN and HGCN embeddings at the first and last layers in Figure 3. We train HGCN with 3-dimensional hyperbolic embeddings and map them to the Poincaré disk which is better for visualization. In contrast to GCN, tree structure is preserved in HGCN, where nodes close to the center are higher in the hierarchy of the tree. This way HGCN smoothly transforms Euclidean features to Hyperbolic embeddings that preserve node hierarchy.

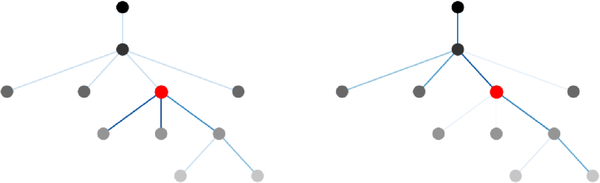

Figure 5 shows the attention weights in the 2-hop neighborhood of a center node (red) for the Disease dataset. The red node is the node where we compute attention. The darkness of the color for other nodes denotes their hierarchy. The attention weights for nodes in the neighborhood are visualized by the intensity of edges. We observe that in HGCN the center node pays more attention to its (grand)parent. In contrast to Euclidean GAT, our aggregation with attention in hyperbolic space allows us to pay more attention to nodes with high hierarchy. Such attention is crucial to good performance in DISEASE, because only sick parents will propagate the disease to their children.

Figure 5:

Attention: Euclidean GAT (left), HGCN (right). Each graph represents a 2-hop neighborhood of the DISEASE-M dataset.

6. Conclusion

We introduced HGCN, a novel architecture that learns hyperbolic embeddings using graph convolutional networks. In HGCN, the Euclidean input features are successively mapped to embeddings in hyperbolic spaces with trainable curvatures at every layer. HGCN achieves new state-of-the-art in learning embeddings for real-world hierarchical and scale-free graphs.

Acknowledgments

Jure Leskovec is a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub investigator. This research has been supported in part by DARPA under FA865018C7880 (ASED), (MSC); NIH under No. U54EB020405 (Mobilize); ARO under MURI; IARPA under No. 2017–17071900005 (HFC), NSF under No. OAC-1835598 (CINES); Stanford Data Science Initiative, Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, JD.com, Amazon, Boeing, Docomo, Huawei, Hitachi, Observe, Siemens, and UST Global. We gratefully acknowledge the support of DARPA under Nos. FA87501720095 (D3M), FA86501827865 (SDH), and FA86501827882 (ASED); NIH under No. U54EB020405 (Mobilize), NSF under Nos. CCF1763315 (Beyond Sparsity), CCF1563078 (Volume to Velocity), and 1937301 (RTML); ONR under No. N000141712266 (Unifying Weak Supervision); the Moore Foundation, NXP, Xilinx, LETI-CEA, Intel, IBM, Microsoft, NEC, Toshiba, TSMC, ARM, Hitachi, BASF, Accenture, Ericsson, Qualcomm, Analog Devices, the Okawa Foundation, American Family Insurance, Google Cloud, Swiss Re, TOTAL, and members of the Stanford DAWN project: Teradata, Facebook, Google, Ant Financial, NEC, VMWare, and Infosys. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation thereon. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, policies, or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of DARPA, NIH, ONR, or the U.S. Government.

A. Review of Differential Geometry

We first recall some definitions of differential and hyperbolic geometry.

A.1. Differential geometry

Manifold

An d–dimensional manifold is a topological space that locally resembles the topological space ℝd near each point. More concretely, for each point x on , we can find a homeomorphism (continuous bijection with continuous inverse) between a neighbourhood of x and ℝd. The notion of manifold is a generalization of surfaces in high dimensions.

Tangent space

Intuitively, if we think of as a d–dimensional manifold embedded in ℝd+1, the tangent space at point x on is a d–dimensional hyperplane in ℝd+1 that best approximates around x. Another possible interpretation for is that it contains all the possible directions of curves on passing through x. The elements of are called tangent vectors and the union of all tangent spaces is called the tangent bundle .

Riemannian manifold

A Riemannian manifold is a pair , where is a smooth manifold and is a Riemannian metric, that is a family of smoothly varying inner products on tangent spaces, . Riemannian metrics can be used to measure distances on manifolds.

Distances and geodesics

Let be a Riemannian manifold. For , define the norm of v by . Suppose is a smooth curve on . Define the length of γ by:

Now with this definition of length, every connected Riemannian manifold becomes a metric space and the distance is defined as:

Geodesic distances are a generalization of straight lines (or shortest paths) to non-Euclidean geometry. A curve is geodesic if d(γ(t), γ(s)) = L(γ|[t,s])∀(t, s) ∈ [a, b](t < s).

Parallel transport

Parallel transport is a generalization of translation to non-Euclidean geometry. Given a smooth manifold , parallel transport Px→y(·) maps a vector to . In Riemannian geometry, parallel transport preserves the Riemannian metric tensor (norm, inner products…).

Curvature

At a high level, curvature measures how much a geometric object such as surfaces deviate from a flat plane. For instance, the Euclidean space has zero curvature while spheres have positive curvature. We illustrate the concept of curvature in Figure 6.

Figure 6:

From left to right: a surface of negative curvature, a surface of zero curvature, and a surface of positive curvature.

A.2. Hyperbolic geometry

Hyperbolic space

The hyperbolic space in d dimensions is the unique complete, simply connected d−dimensional Riemannian manifold with constant negative sectional curvature. There exist several models of hyperbolic space such as the Poincaré model or the hyperboloid model (also known as the Minkowski model or the Lorentz model). In what follows, we review the Poincaré and the hyperboloid models of hyperbolic space as well as connections between these two models.

A.2.1. Poincaré ball model

Let ||.||2 be the Euclidean norm. The Poincaré ball model with unit radius and constant negative curvature −1 in d dimensions is the Riemannian manifold (,(gx)x) where

and

where and Id is the identity matrix. The induced distance between two points (x, y) in can be computed as:

A.2.2. Hyperboloid model

Hyperboloid model

Let denote the Minkowski inner product,

The hyperboloid model with unit imaginary radius and constant negative curvature −1 in d dimensions is defined as the Riemannian manifold (ℍd,1, (gx)x) where

and

The induced distance between two points (x, y) in ℍd,1 can be computed as:

Geodesics

We recall a result that gives the unit speed geodesics in the hyperboloid model with curvature −1 [33]. This result can be used to show Propositions 3.1 and 3.2 for the hyperboloid manifold with negative curvature −1/K, and then learn K as a model parameter in HGCN.

Theorem A.1

Let x ∈ ℍd,1 and unit-speed (i.e. ). The unique unit-speed geodesic γx→u : [0,1] → ℍd,1 such that γx→u(0) = x and is given by:

Parallel Transport

If two points x and y on the hyperboloid ℍd,1 are connected by a geodesic, then the parallel transport of a tangent vector to the tangent space is:

| (15) |

Projections

Finally, we recall projections to the hyperboloid manifold and its corresponding tangent spaces. A point x = (x0, x1:d) ∈ ℝd+1 can be projected on the hyperboloid manifold ℍd,1 with:

| (16) |

Similarly, a point v ∈ ℝd+1 can be projected on with:

| (17) |

In practice, these projections are very useful for optimization purposes as they constrain embeddings and tangent vectors to remain on the manifold and tangent spaces.

A.2.3. Connection between the Poincaré ball model and the hyperboloid model

While the hyperboloid model tends to be more stable for optimization than the Poincaré model [30], the Poincaré model is very interpretable and embeddings can be directly visualized on the Poincaré disk. Fortunately, these two models are isomorphic (cf. Figure 7) and there exist a diffeomorphism mapping one space onto the other:

| (18) |

| (19) |

Figure 7:

Illustration of the hyperboloid model (top) in 3 dimensions and its connection to the Poincaré disk (bottom).

B. Proofs of Results

B.1. Hyperboloid model of hyperbolic space

For completeness, we re-derive results of hyperbolic geometry for any arbitrary curvature. Similar derivations can be found in the literature [43].

Proposition 3.1

Let x ∈ ℍd,K, be unit-speed. The unique unit-speed geodesic γx→u(·) such that γx→u(0) = x, is , and the intrinsic distance function between two points x, y in ℍd,K is then:

| (4) |

Proof. Using theorem A.1, we know that the unique unit-speed geodesic γy→u(.) in ℍd,1 must satisfy

and is given by

Now let x ∈ ℍd,K and be unit-speed and denote the unique unit-speed geodesic in ℍd,K such that and . Let us define and . We have,

and since is the unique unit-speed geodesic in ℍd,K, we also have

Furthermore, we have y ∈ ℍd,1, as and .

Therefore ϕy→u(.) is a unit-speed geodesic in ℍd,1 and we get

Finally, this leads to

□

Proposition 3.2

For x ∈ ℍd,K, and y ∈ ℍd,K such that v ≠ 0 and y ≠ x, the exponential and logarithmic maps of the hyperboloid model are given by:

Proof. We use a similar reasoning to that in Corollary 1.1 in [11]. Let be the unique geodesic such that and . Let us define where is the Minkowski norm of v and

ϕx→u(t) satisfies,

Therefore is a unit-speed geodesic in ℍd,K and we get

By identification, this leads to

We can use this result to derive exponential and logarthimic maps on the hyperboloid model. We know that . Therefore we get,

Now let . We have as and . Therefore and we get

where is well defined since . Note that,

as . Therefore, we finally have

□

B.2. Curvature

Lemma 1

For any hyperbolic spaces with constant curvatures −1/K, −1/K′ > 0, and any pair of hyperbolic points (u, v) embedded in ℍd,K, there exists a mapping to another pair of corresponding hyperbolic points in , (ϕ(u), ϕ(v)) such that the Minkowski inner product is scaled by a constant factor.

Proof. For any hyperbolic embedding x = (x0, x1, …, xd) ∈ ℍd,K we have the identity: . For any hyperbolic curvature −1/K < 0, consider the mapping . Then we have the identity and therefore . For any pair (u, v), . The factor only depends on curvature, but not the specific embeddings. □

Lemma 1 implies that given a set of embeddings learned in hyperbolic space ℍd,K, we can find embeddings in another hyperbolic space with different curvature, , such that the Minkowski inner products for all pairs of embeddings are scaled by the same factor .

For link prediction tasks, Theorem 4.1 shows that with infinite precision, the expressive power of hyperbolic spaces with varying curvatures is the same.

Theorem 4.1

For any hyperbolic curvatures −1/K, −1/K′ < 0, for any node embeddings H = {hi} ⊂ ℍd,K of a graph G, we can find , , such that the reconstructed graph from H′ via the Fermi-Dirac decoder is the same as the reconstructed graph from H, with different decoder parameters (r, t) and (r′, t′).

Proof. The Fermi-Dirac decoder predicts that there exists a link between node i and j , where b ∈ (0, 1) is the threshold for determining existence of links. The criterion is equivalent to .

Given H = {h1,…,hn}, the graph GH reconstructed with the Fermi-Dirac decoder has the edge set . Consider the mapping to ,. Let . By Lemma 1,

| (20) |

Due to linearity, we can find decoder parameter, r′ and t′ that satisfy . With such r′, t′, the criterion is equivalent to . Therefore, the reconstructed graph based on the set of embeddings H′ is identical to GH. □

C. Experimental Details

C.1. Dataset statistics

We detail the dataset statistics in Table 3.

Table 3:

Benchmarks’ statistics

| Name | Nodes | Edges | Classes | Node features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cora | 2708 | 5429 | 7 | 1433 |

| Pubmed | 19717 | 88651 | 3 | 500 |

| Human PPI | 17598 | 5429 | 4 | 17 |

| Airport | 3188 | 18631 | 4 | 4 |

| Disease | 1044 | 1043 | 2 | 1000 |

| Disease-M | 43193 | 43102 | 2 | 1000 |

C.2. Training details

Here we present details of HGCN’s training pipeline, with optimization and incorporation of DropConnect [42].

Parameter optimization

Recall that linear transformations and attention are defined on the tangent space of points. Therefore the linear layer and attention parameters are Euclidean. For bias, there are two options: one can either define parameters in hyperbolic space, and use hyperbolic addition operation [10], or define parameters in Euclidean space, and use Euclidean addition after transforming the points into the tangent space. Through experiments we find that Euclidean optimization is much more stable, and gives slightly better test performance compared to Riemannian optimization, if we define parameters such as bias in hyperbolic space. Hence different from shallow hyperbolic embeddings, although our model and embeddings are hyperbolic, the learnable graph convolution parameters can be optimized via Euclidean optimization (Adam Optimizer [19]), thanks to exponential and logarithmic maps. Note that to train shallow Poincaré embeddings, we use Riemannian Stochastic Gradient Descent [4, 48], since its model parameters are hyperbolic. We use early stopping based on validation set performance with a patience of 100 epochs.

Drop connection

Since rescaling vectors in hyperbolic space requires exponential and logarithmic maps, and is conceptually not tied to the inverse dropout rate in terms of re-normalizing L1 norm, Dropout cannot be directly applied in HGCN. However, as a result of using Euclidean parameters in HGCN, DropConnect [42], the generalization of Dropout, can be used as a regularization. DropConnect randomly zeros out the neural network connections, i.e. elements of the Euclidean parameters during training time, improving the generalization of HGCN.

Projections

Finally, we apply projections similar to Equations 16 and 17 for the hyperboloid model ℍd,K after each feature transform and log or exp map, to constrain embeddings and tangent vectors to remain on the manifold and tangent spaces.

Footnotes

Project website with code and data: http://snap.stanford.edu/hgcn

The equivalent of GCN in link prediction is GAE [20]. We did not compare link prediction GNNs based on shallow embeddings such as [49] since they are not inductive.

HGCN uses DropConnect [42], as described in Appendix C.

Code available at http://snap.stanford.edu/hgcn. We provide HGCN implementations for hyperboloid and Poincaré models. Empirically, both models give similar performance but hyperboloid model offers more stable optimization, because Poincaré distance is numerically unstable [30].

References

- [1].Adcock Aaron B, Sullivan Blair D, and Mahoney Michael W. Tree-like structure in large social and information networks. In 2013 IEEE 13th International Conference on Data Mining, pages 1–10. IEEE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Anderson Roy M and May Robert M. Infectious diseases of humans: dynamics and control. Oxford university press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Belkin Mikhail and Niyogi Partha. Laplacian eigenmaps and spectral techniques for embedding and clustering. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 585–591, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bonnabel Silvere. Stochastic gradient descent on riemannian manifolds. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Benjamin Paul Chamberlain James Clough, and Deisenroth Marc Peter. Neural embeddings of graphs in hyperbolic space. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.10359, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chen Wei, Fang Wenjie, Hu Guangda, and Mahoney Michael W. On the hyperbolicity of small-world and treelike random graphs. Internet Mathematics, 9(4):434–491, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Clauset Aaron, Moore Cristopher, and Newman Mark EJ. Hierarchical structure and the prediction of missing links in networks. Nature, 453(7191):98, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dhingra Bhuwan, Shallue Christopher J, Norouzi Mohammad, Dai Andrew M, and Dahl George E. Embedding text in hyperbolic spaces. NAACL HLT, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fréchet Maurice. Les éléments aléatoires de nature quelconque dans un espace distancié. In Annales de l’institut Henri Poincaré, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ganea Octavian, Bécigneul Gary, and Hofmann Thomas. Hyperbolic neural networks. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 5345–5355, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ganea Octavian-Eugen, Becigneul Gary, and Hofmann Thomas. Hyperbolic entailment cones for learning hierarchical embeddings. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 1632–1641, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Grover Aditya and Leskovec Jure. node2vec: Scalable feature learning for networks. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining, pages 855–864. ACM, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gu Albert, Sala Frederic, Gunel Beliz, and Ré Christopher. Learning mixed-curvature representations in product spaces. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gulcehre Caglar, Denil Misha, Malinowski Mateusz, Razavi Ali, Pascanu Razvan, Karl Moritz Hermann Peter Battaglia, Bapst Victor, Raposo David, Santoro Adam, et al. Hyperbolic attention networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hamilton Will, Ying Zhitao, and Leskovec Jure. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 1024–1034, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ioffe Sergey and Szegedy Christian. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 448–456, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jonckheere Edmond, Lohsoonthorn Poonsuk, and Bonahon Francis. Scaled gromov hyperbolic graphs. Journal of Graph Theory, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Khrulkov Valentin, Mirvakhabova Leyla, Ustinova Evgeniya, Oseledets Ivan, and Lempitsky Victor . Hyperbolic image embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.02239, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kingma Diederik P and Ba Jimmy. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kipf Thomas N and Welling Max. Variational graph auto-encoders. NeurIPS Workshop on Bayesian Deep Learning, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kipf Thomas N and Welling Max. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kleinberg Robert. Geographic routing using hyperbolic space. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Communications, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Krioukov Dmitri, Papadopoulos Fragkiskos, Kitsak Maksim, Vahdat Amin, and Marián Boguná. Hyperbolic geometry of complex networks. Physical Review E, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kruskal Joseph B. Multidimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to a nonmetric hypothesis. Psychometrika, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Li Yujia, Tarlow Daniel, Brockschmidt Marc, and Zemel Richard. Gated graph sequence neural networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Liu Qi, Nickel Maximilian, and Kiela Douwe. Hyperbolic graph neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Namata Galileo, London Ben, Getoor Lise, Huang Bert, and UMD EDU. Query-driven active surveying for collective classification. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Narayan Onuttom and Saniee Iraj. Large-scale curvature of networks. Physical Review E, 84(6):066108, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nickel Maximillian and Kiela Douwe. Poincaré embeddings for learning hierarchical representations. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 6338–6347, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nickel Maximillian and Kiela Douwe. Learning continuous hierarchies in the lorentz model of hyperbolic geometry. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 3776–3785, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Perozzi Bryan, Al-Rfou Rami, and Skiena Steven. Deepwalk: Online learning of social representations. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining, pages 701–710. ACM, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ravasz Erzsébet and Barabási Albert-László. Hierarchical organization in complex networks. Physical review E, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Robbin Joel W and Salamon Dietmar A. Introduction to differential geometry. ETH, Lecture Notes, preliminary version, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sala Frederic, Chris De Sa Albert Gu, and Christopher Ré. Representation tradeoffs for hyperbolic embeddings. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 4457–4466, 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sarkar Rik. Low distortion delaunay embedding of trees in hyperbolic plane. In International Symposium on Graph Drawing, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sen Prithviraj, Namata Galileo, Bilgic Mustafa, Getoor Lise, Galligher Brian, and Eliassi-Rad Tina. Collective classification in network data. AI magazine, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Szklarczyk Damian, John H Morris Helen Cook, Kuhn Michael, Wyder Stefan, Simonovic Milan, Santos Alberto, Nadezhda T Doncheva Alexander Roth, Bork Peer, et al. The string database in 2017: quality-controlled protein–protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic acids research, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tay Yi, Tuan Luu Anh, and Hui Siu Cheung. Hyperbolic representation learning for fast and efficient neural question answering. In Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, pages 583–591. ACM, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tifrea Alexandru, Becigneul Gary, and Ganea Octavian-Eugen. Poincaré glove: Hyperbolic word embeddings. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [40].van de Leemput Joyce, Boles Nathan C, Kiehl Thomas R, Corneo Barbara, Lederman Patty, Menon Vilas, Lee Changkyu, Martinez Refugio A, Levi Boaz P, Thompson Carol L, et al. Cortecon: a temporal transcriptome analysis of in vitro human cerebral cortex development from human embryonic stem cells. Neuron, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Veličković Petar, Cucurull Guillem, Casanova Arantxa, Romero Adriana, Lio Pietro, and Bengio Yoshua. Graph attention networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wan Li, Zeiler Matthew, Zhang Sixin, Cun Yann Le, and Fergus Rob. Regularization of neural networks using dropconnect. In International conference on machine learning, pages 1058–1066, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wilson Richard C, Hancock Edwin R, Pekalska Elżbieta, and Duin Robert PW. Spherical and hyperbolic embeddings of data. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 36(11):2255–2269, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wu Felix, Souza Amauri, Zhang Tianyi, Fifty Christopher, Yu Tao, and Weinberger Kilian. Simplifying graph convolutional networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 6861–6871, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Xu Keyulu, Hu Weihua, Leskovec Jure, and Jegelka Stefanie. How powerful are graph neural networks? In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Yang Zhilin, Cohen William, and Salakhudinov Ruslan. Revisiting semi-supervised learning with graph embeddings. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 40–48, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ying Rex, He Ruining, Chen Kaifeng, Eksombatchai Pong, Hamilton William L, and Leskovec Jure. Graph convolutional neural networks for web-scale recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, pages 974–983. ACM, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhang Hongyi, Sashank J Reddi, and Suvrit Sra. Riemannian svrg: Fast stochastic optimization on riemannian manifolds. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 4592–4600, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zhang Muhan and Chen Yixin. Link prediction based on graph neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 5165–5175, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zitnik Marinka, Marcus W Feldman Jure Leskovec, et al. Evolution of resilience in protein interactomes across the tree of life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(10):4426–4433, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]