Potyviruses include numerous economically important viruses that represent approximately 30% of known plant viruses. However, there is still limited information about the mechanism of potyviral cell-to-cell movement. Here, we show that P3N-PIPO interacts with and recruits CI to the PD via the PIPO domain and interacts with P3 via the shared P3N domain. We further report that the interaction of P3N-PIPO and P3 is associated with 6K2 vesicles and brings the 6K2 vesicles into proximity with PD-located CI structures. These results support the notion that the replication and cell-to-cell movement of potyviruses are processes coupled by anchoring viral replication complexes at the entrance of PDs, which greatly increase our knowledge of the intercellular movement of potyviruses.

KEYWORDS: 6K2, CI, P3, P3N-PIPO, cell-to-cell movement, potyvirus, replication

ABSTRACT

P3N-PIPO, the only dedicated movement protein (MP) of potyviruses, directs cylindrical inclusion (CI) protein from the cytoplasm to the plasmodesma (PD), where CI forms conical structures for intercellular movement. To better understand potyviral cell-to-cell movement, we further characterized P3N-PIPO using Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) as a model virus. We found that P3N-PIPO interacts with P3 via the shared P3N domain and that TuMV mutants lacking the P3N domain of either P3N-PIPO or P3 are defective in cell-to-cell movement. Moreover, we found that the PIPO domain of P3N-PIPO is sufficient to direct CI to the PD, whereas the P3N domain is necessary for localization of P3N-PIPO to 6K2-labeled vesicles or aggregates. Finally, we discovered that the interaction between P3 and P3N-PIPO is essential for the recruitment of CI to cytoplasmic 6K2-containing structures and the association of 6K2-containing structures with PD-located CI inclusions. These data suggest that both P3N and PIPO domains are indispensable for potyviral cell-to-cell movement and that the 6K2 vesicles in proximity to PDs resulting from multipartite interactions among 6K2, P3, P3N-PIPO, and CI may also play an essential role in this process.

IMPORTANCE Potyviruses include numerous economically important viruses that represent approximately 30% of known plant viruses. However, there is still limited information about the mechanism of potyviral cell-to-cell movement. Here, we show that P3N-PIPO interacts with and recruits CI to the PD via the PIPO domain and interacts with P3 via the shared P3N domain. We further report that the interaction of P3N-PIPO and P3 is associated with 6K2 vesicles and brings the 6K2 vesicles into proximity with PD-located CI structures. These results support the notion that the replication and cell-to-cell movement of potyviruses are processes coupled by anchoring viral replication complexes at the entrance of PDs, which greatly increase our knowledge of the intercellular movement of potyviruses.

INTRODUCTION

Plant viruses have to spread from the primarily infected cells to neighboring cells and to remote tissues to establish a systemic infection. Unlike animal counterparts that move between cells via endocytosis (1), plant viruses move through the narrow plasmodesma (PD) on the cell membrane (2). Plant viruses have evolved specific proteins, namely, viral movement proteins (MPs), to accomplish this process. The MPs encoded by viruses of different taxonomic groups share no extensive sequence similarity, indicating that they evolved independently (3, 4). For instance, Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) of the genus Tobamovirus uses a single MP to accomplish intercellular movement (5), whereas viruses of the genus Potexvirus need at least four proteins to do so, including the three triple-gene-block products and coat protein (CP) (6). Uncovering the mechanism of intercellular movement is one of the major objectives in plant virology research.

The genus Potyvirus in the family Potyviridae consists of a group of plant viruses with monopartite, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome (+ssRNA) of approximately 9.6 kb (7). The 5′ end of the genome is covalently linked to a viral VPg protein, whereas the 3′ end is polyadenylated (7). In addition to the two short untranslated regions at the 5′ and 3′ ends, the rest of the genome encodes a long open reading frame (ORF), which is translated into a large polypeptide, approximately 350 kDa (8). The polypeptide is proteolyzed by three viral proteinases, namely, P1, HcPro, and Pro, into 10 mature proteins, which, from N to C terminus, are P1, HcPro, P3, 6K1, CI, 6K2, VPg, Pro, NIb, and CP (9). In addition, a conserved polymerase slippage motif (5′-GAAAAAA-3′) in the P3 cistron enables the expression of an additional protein named P3N-PIPO (the N-terminal half of P3 fused to Pretty Interesting Potyvirus ORF) (10–12).

P3N-PIPO, the only dedicated potyviral MP (13, 14), localizes to the plasma membrane and PD possibly via interaction with PCaP1, a plasma membrane-localized cation binding protein (15, 16). Interestingly, a group 1 remorin (REM1.2) negatively regulates the cell-to-cell movement of Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) by competing with PCaP1 (17). P3N-PIPO also interacts with several host factors (18, 19); however, the roles of these interactions in potyviral intercellular movement still need to be investigated. P3N-PIPO interacts with CI via its C-terminal PIPO domain and directs CI to the PD to form a conical structure for intercellular movement (16, 20). CP is also indispensable for movement, since Tobacco etch virus (TEV) mutants containing CPs with a substitution of the highly conserved Ser122 within the core domain or with a 17-amino-acid (aa) deletion at the C-terminal domain and Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) mutants containing CPs with single substitutions of the charged amino acids in the C-proximal region are defective in movement (21, 22). Moreover, CP associates with PD-located conical CI and was found inside the PD channel during infections with Pea seed-borne mosaic virus (PSbMV) and Tobacco vein mottling virus (TVMV) (23, 24). Thus, it is believed that potyviral genomes are transported by PD-located, conical CI inclusions as intact virions or CP-associated RNP complexes (RNPs). The replication of potyviruses occurs in 6K2-induced vesicles or aggregates (25, 26). Previous studies have shown that 6K2 vesicles may also play a role in potyviral intercellular movement since these motile vesicles were docked at the PD-located CI during TuMV infection (27). However, how 6K2 vesicles are recruited to the PD and the function of these PD-docked 6K2 vesicles remain to be understood. Here, we show that P3N-PIPO interacts with P3 via the shared N terminus and that this interaction is essential for viral cell-to-cell movement, possibly through recruitment of 6K2-induced vesicles to the PD by P3. These results thus provide novel information on the cell-to-cell movement of potyviruses.

RESULTS

P3N-PIPO interacts with P3 via the shared N-terminal domain.

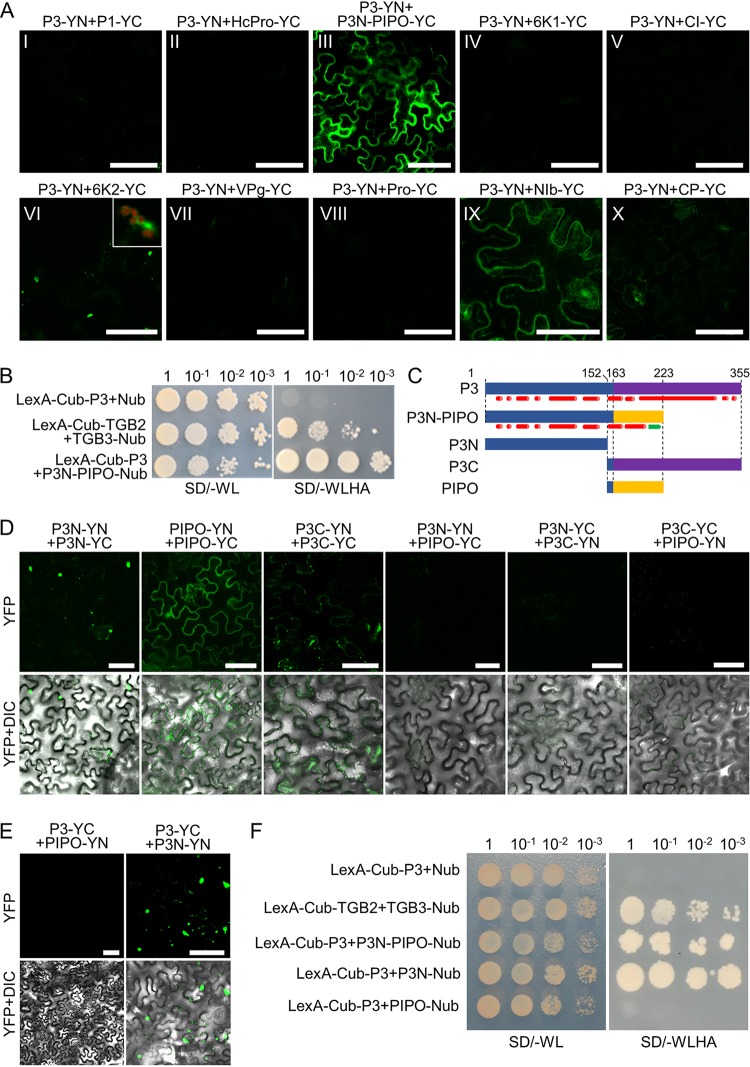

The interactome of potyviral proteins, except P3N-PIPO, of several potyviruses has been extensively studied by yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays (28–33). Despite the important roles of P3 in potyviral replication and pathogenicity (13, 34), it was found to interact only weakly with NIb by Y2H and colocalize with 6K2 vesicles (31, 35). To further characterize the P3 interactome, a bimolecular fluorescent complementation (BiFC) assay was performed between P3 and 10 other proteins encoded by Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV). The N-terminal domain of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-fused P3 (P3-YN) was transiently expressed with 10 other potyviral proteins that were fused with the C-terminal domain of YFP (YC) at the C terminus in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves and visualized by confocal microscopy at 48 h postinoculation (hpi). Consistent with previous studies (31, 35), fluorescence was observed in cells expressing P3-YN and 6K2-YC or NIb-YC (Fig. 1A). Fluorescent signal from the interaction between P3 and 6K2 was observed at the surface of chloroplasts and in the cytoplasm as aggregates (Fig. 1A, frame VI), whereas the smeared fluorescent signal from the interaction between P3 and NIb was recorded at the cell periphery (Fig. 1A, frame IX). Interestingly, bright fluorescence signals were also observed in the cells expressing P3-YN and P3N-PIPO-YC (Fig. 1A, frame III), suggesting that P3 may interact with P3N-PIPO. A split-ubiquitin-based membrane yeast two-hybrid (MYTH) assay was performed to confirm the interaction. Potato virus X (PVX, a potexvirus)-encoded TGB2 and TGB3 were used as positive controls, as their interaction has been studied extensively (36–38). The yeast strain NMY51 harboring LexA-Cub-TGBp2 and Nub-TGBp3 survived on selective medium lacking tryptophan, leucine, histidine, and adenine (−WLHA), whereas yeast cells cotransformed with LexA-Cub-P3 and Nub failed to grow on the selective medium, confirming the specificity of the system (Fig. 1B). The yeast transformants harboring LexA-Cub-P3 and P3N-PIPO-Nub also grew on the selective medium (Fig. 1B), confirming that P3 interacts with P3N-PIPO.

FIG 1.

P3N-PIPO interacts with P3 via the shared P3N domain. (A) BiFC assay for protein-protein interactions between P3 and 10 other TuMV-encoded proteins. Micrographs were obtained at 48 hpi using the same parameters. The chloroplast fluorescence is included in the inset in frame VI to show the typical localization of the YFP signal from the interaction between P3 and 6K2. Scale bars = 50 μm. (B) MYTH assay for protein-protein interaction between P3N-PIPO and P3. PVX TGB2 and TGB3 were used as positive controls. (C) Schematic representations of the P3N-PIPO and P3 domains. The numbers represent the amino acid positions of the domain boundaries, and the predicted protein secondary structures of P3 and P3N PIPO are indicated below each protein. The predicted α-helixes and β-sheets are shown as red cylinders and green arrows, respectively. (D) BiFC assay for protein-protein interactions among the P3N, P3C, and PIPO domains. Differential interference contrast (DIC) channels are included to show the cell outlines. Micrographs were obtained at 48 hpi using the same parameters. Scale bars = 50 μm. (E) BiFC for protein-protein interactions between P3 and PIPO or P3N in N. benthamiana epidermal cells at 48 hpi. DIC channels are included to show the cell outlines. Scale bars = 50 μm. (F) MYTH assays for protein-protein interactions among P3N, P3C, and PIPO.

P3N-PIPO and P3 share the same N-terminal part, which raises the possibility that they interact with each other via the shared N-terminal domain. Therefore, P3N-PIPO and P3 were divided into three nonreported domains based on their predicted secondary structures, namely, P3N, PIPO, and P3C (Fig. 1C). The C-terminal 11 aa of P3N (aa 153 to 163) were retained in P3C and PIPO to avoid disrupting the predicted α-helix (Fig. 1C). Bright granular or smeared fluorescence signals were observed in the N. benthamiana cells expressing YN- and YC-fused P3N or PIPO, and a weak diffuse fluorescence signal was observed in the cells expressing YN- and YC-fused P3C (Fig. 1D), whereas no fluorescence signal was detected in the cells expressing P3N plus P3C, P3N plus PIPO, or P3C plus PIPO fused to either YN or YC (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that P3N, PIPO, and P3C self-interact but cannot interact with each other. Indeed, P3 interacted only with P3N and not PIPO in the BiFC (Fig. 1E) and MYTH assays (Fig. 1F). Together these data confirmed that P3N-PIPO interacts with P3 via the shared P3N domain.

P3N is essential for TuMV intercellular movement.

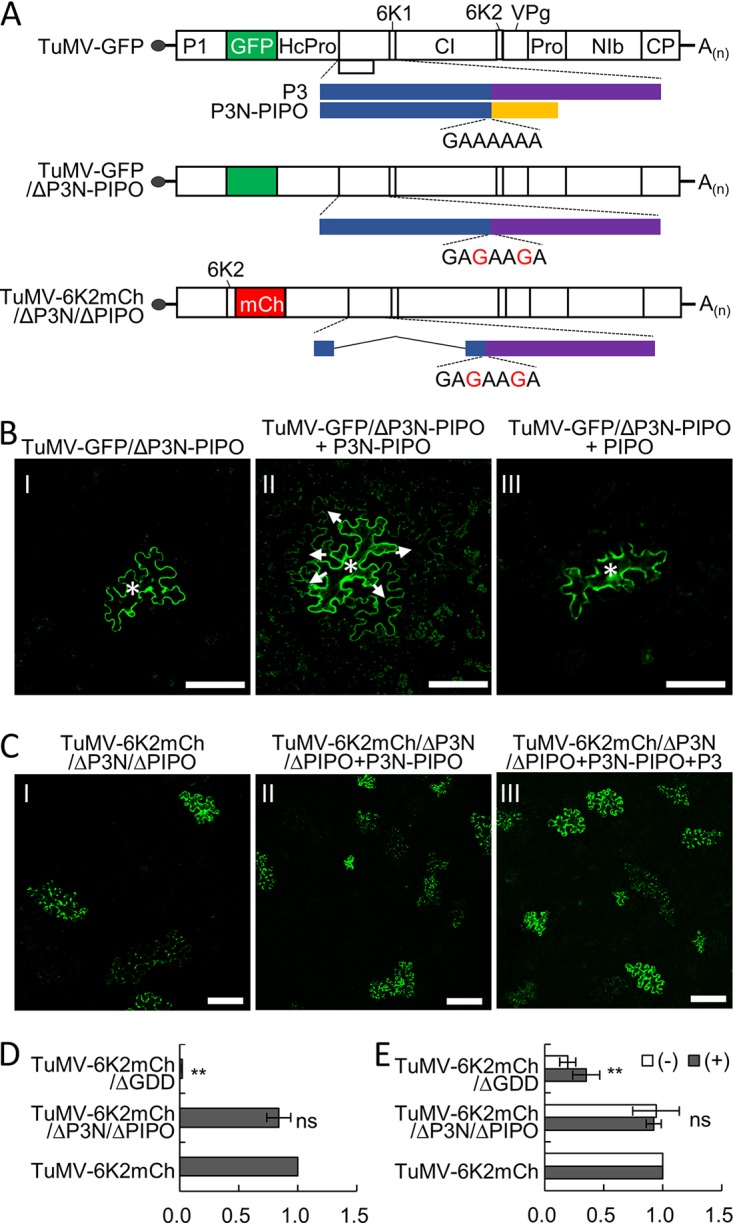

P3N-PIPO is dispensable for virus replication, since P3N-PIPO knockout mutants of TuMV or SMV accumulate levels of genomic RNA comparable to those accumulated by the wild-type virus (14, 39). We thus suspected that the interaction between P3 and P3N-PIPO might have a role in viral movement. TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO (Fig. 2A), a P3N-PIPO deletion TuMV infectious clone carrying a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene between P1 and HcPro, was constructed by mutating the polymerase spillage motif into 5′-GAGAAGA-3′ in TuMV-GFP (40) and was used to assess cell-to-cell movement by in trans expression of P3N-PIPO or PIPO. In this experiment, Agrobacterium tumefaciens cultures harboring TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO were diluted to low concentrations, e.g., an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.001, so that isolated cells became infected and the GFP expressed from TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO was restricted to single cells. In the N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated by TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO only, the majority of the infection foci analyzed (30 out of 35) contained only one GFP-expressing cell (Fig. 2B, frame I), with a few (5 out of 35) foci comprising two-cell clusters at 3 days postinoculation (dpi), and no GFP-expressing foci containing more than three cells were observed during the survey (Table 1). In the N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated by TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO and P3N-PIPO, most of the analyzed infection foci (35 out of 46) contain three or more GFP-expressing cells at 3 dpi (Fig. 2B, frame II; Table 1). Subsequent reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses confirmed that the introduced mutations in the polymerase spillage motif were maintained in the viral progenies. Thus, transiently expressed P3N-PIPO can complement the movement defect of TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO. However, most infection foci (57 out of 60) contained only one or two GFP-expressing cells in the N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO and PIPO (Fig. 3B, frame III; Table 1), suggesting that P3N is indispensable for intercellular movement.

FIG 2.

Cell-to-cell movement complementation assays. (A) Schematic representations of TuMV-GFP, TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO, and TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO. White boxes indicate the polyprotein cleavage products and the green and red boxes indicate GFP and mCherry (mCh) reporters, respectively. The polymerase spillage motif (5′-GAAAAAA-3′) or its mutations at the 5′ end of the PIPO ORF are also indicated. (B and C) The P3N domain of both P3 and P3N-PIPO is essential for cell-to-cell movement. Agrobacterium cultures harboring TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO or TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO were infiltrated at an OD600 value of 0.001, and Agrobacterium cultures harboring P3N-PIPO, PIPO, or P3 were infiltrated at an OD600 value of 0.2. The white asterisks and white arrows indicate the original and secondary infection cells, respectively, in panel B. Note that the fluorescence from 6K2-mCherry was pseudocolored into green for clarity in panel C. All micrographs were taken at 3 dpi with the same parameters. Scale bars = 50 μm. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses of the genomic RNA levels of TuMV-6K2mCh and its mutants in N. benthamiana leaves at 36 hpi. The accumulation of TuMV-6K2mCh genomic RNA was linearized to 1, and the N. benthamiana actin II gene was used as the internal control. **, P < 0.01 (Student’s t test). ns, no significant difference. (E) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses of the genomic RNA levels of TuMV-6K2mCh and its mutants in N. benthamiana protoplasts at 36 hpi. The positive-sense and negative-sense genomic RNAs of TuMV-6K2mCh were linearized to 1, and the N. benthamiana actin II gene was used as an internal control. **, P < 0.01 (Student’s t test).

TABLE 1.

Trans-complementation of cell-to-cell movement of TuMV mutants

| Plasmid combination | No. of foci containing: |

Total no. of foci counted | Movement efficiency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 cell | 2 or 3 cells | ≥4 cells | |||

| TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO | 30 | 5 | 0 | 35 | 0 |

| TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO + P3NPIPO | 3 | 8 | 35 | 46 | 76.1 |

| TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO + PIPO | 44 | 13 | 3 | 60 | 5.0 |

| TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO | 32 | 7 | 3 | 43 | 7.0 |

| TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO + P3N-PIPO | 33 | 8 | 1 | 42 | 2.4 |

| TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO + P3N-PIPO + P3 | 44 | 11 | 3 | 57 | 5.3 |

FIG 3.

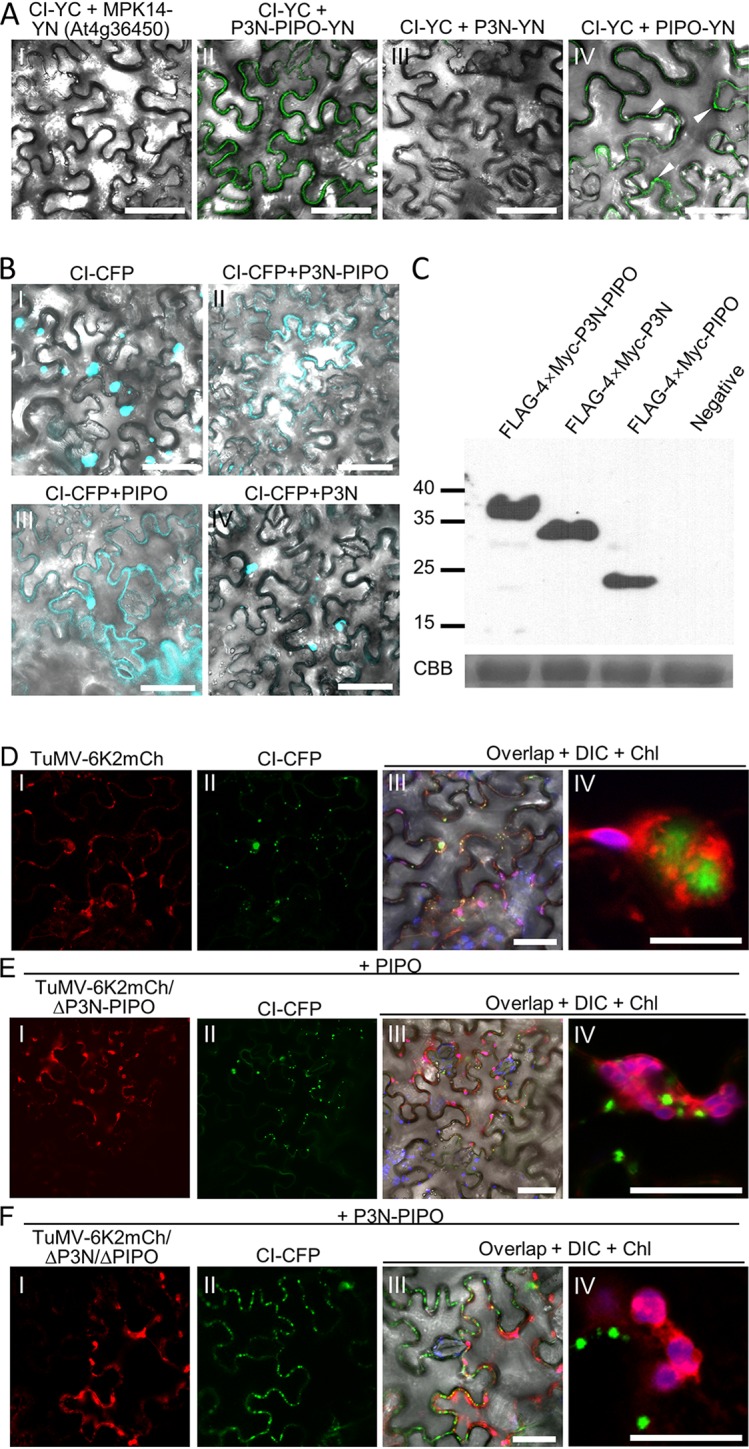

The PIPO domain is sufficient for redirecting CI to PDs. (A) BiFC assay for protein-protein interactions between CI and P3N-PIPO, P3N, or PIPO. Micrographs were obtained at 48 hpi using the same parameters. The DIC channels are included to show cell outlines. The fluorescent foci from the interaction between CI-YC and PIPO-YN are indicated by white arrowheads. Scale bars = 50 μm. (B) Influence of P3N-PIPO, P3N, and PIPO on the subcellular localization of CI-CFP in N. benthamiana epidermal cells at 48 hpi. The DIC channels are included to show cell outlines. Scale bars = 50 μm. (C) Immunoblotting analyses of transiently expressed P3N-PIPO, P3N, and PIPO in panel A using polyclonal antibodies against the Myc tag. At the bottom is a parallel gel stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (CBB) to show the equal loading of protein samples. Numbers at the left are molecular masses, in kilodaltons. (D to F) In vivo visualization of CI-CFP in N. benthamiana epidermal cells infected by wild-type TuMV-6K2mCh (D), TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO (E), or TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO (F) at 60 hpi. Nonfluorescent PIPO and P3N-PIPO were coinfiltrated with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO and TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO, respectively. The DIC is included in frame III to show the edge of cells, and chloroplast (Chl) fluorescence is included in frames III and IV to distinguish 6K-induced aggregates. Scale bars = 50 (frames I to III) and 10 (frame IV) μm.

To understand whether the P3N domain of P3 is also required for cell-to-cell movement, a TuMV mutant named TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO was constructed (Fig. 2A), in which the sequence encoding aa 5 to 152 of the P3N domain was deleted and the conserved polymerase slippage motif was also mutated into 5′-GAGAAGA-3′ to avoid the expression of N-terminally truncated P3N-PIPO. This infectious clone also carried an mCherry-fused 6K2 (6K2-mCherry) reporter gene between the P1 and HcPro cistrons for distinguishing virus-infected cells and to label viral replication vesicles in the infected cells. The movement ability of TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO was evaluated as described above. The fluorescence signal of TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO was mostly (40 out of 43) restricted to one or two cells at 3 dpi (Fig. 2C, frame I; Table 1), suggesting that TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO is also defective in cell-to-cell movement. The addition of P3N-PIPO did not restore its cell-to-cell movement ability (Fig. 2C, frame II; Table 1). Unexpectedly, the fluorescence of TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO was still dominantly restricted in one or two cells (54 out of 57) in the presence of both P3 and P3N-PIPO (Fig. 2C, frame III; Table 1), indicating that the movement function of P3 cannot be complemented by in trans-expressed P3.

P3 is involved in virus replication by targeting 6K2 vesicles or aggregates (13, 35). To rule out that the incompetent cell-to-cell movement of TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO is due to enervated viral replication, a replication assay was performed. N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with TuMV-6K2mCh, TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO, or a replication-defective infectious clone (TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔGDD), all used at identical quantities. Genomic RNAs were evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) at 36 hpi. The results showed that there were no significant differences in genomic RNA between TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO and TuMV-6K2mCh (Fig. 2D). The replications of TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO and TuMV-6K2mCh were also compared in N. benthamiana protoplasts. No significant differences in positive-sense and negative-sense genomic RNAs were observed between TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO and TuMV-6K2mCh at 36 hpi (Fig. 2E). Together, these data indicate that the P3N of P3 is primarily involved in movement.

P3N is not required for targeting CI to plasmodesmata.

P3N-PIPO functions in cell-to-cell movement by interacting with CI and targeting it to the PD (16). Moreover, a study on Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV) showed that P3N-PIPO interacts with both CI and PCaP1 via its C-terminal PIPO domain (20). BiFC assays showed that TuMV CI also interacts with P3N-PIPO via the PIPO domain (Fig. 3A). The fluorescence signal from the interaction between CI and PIPO was also located primarily at the cell periphery (Fig. 3A, frame IV), suggesting that PIPO may be sufficient to direct CI to the PD. To confirm this possibility, a cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-tagged CI (CI-CFP) was coexpressed with nonfluorescent P3N-PIPO, P3N, or PIPO in N. benthamiana leaves. CI was located in the cytoplasm and nuclei as inclusions of varied sizes (Fig. 3B, frame I), whereas most CI-CFP proteins translocated to the cell periphery in the presence of FLAG-4×Myc-P3N-PIPO (Fig. 3B, frame II). Interestingly, CI was also localized to the cell periphery in the presence of FLAG-4×Myc-PIPO (Fig. 3B, frame III) but was still located in the cytoplasm in the presence of FLAG-4×Myc-P3N (Fig. 3B, frame IV). Western blotting using polyclonal antibodies against the Myc tag confirmed the expression of FLAG-4×Myc-P3N-PIPO, FLAG-4×Myc-P3N, and FLAG-4×Myc-PIPO (Fig. 3C). Together, these results suggested that PIPO but not P3N interacts with CI and directs CI to the PD.

Subcellular localization of CI during infection with wild-type TuMV or its mutants was also analyzed. CI-CFP was coinfiltrated with TuMV-6K2mCh, TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO, or TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO in N. benthamiana leaves. Nonfluorescent PIPO and P3N-PIPO were included with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO and TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO, respectively. The cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh exhibited red fluorescence from 6K2-mCherry, which allowed us to identify virus-infected cells. CI-CFP was located in the cytoplasm and at the cell periphery in the TuMV-6K2mCh-infected cells (Fig. 3D). Noticeably, cytoplasmic CI inclusions were always associated with 6K2-containing aggregates but not colocalized or directly in contact with 6K2 aggregates (Fig. 3D, frame IV). CI is indispensable for both cell-to-cell movement and replication (41–43). However, a direct interaction between CI and 6K2 was not detected using either the BiFC or MYTH assay (data not shown). Thus, it is possible that CI was recruited into replication vesicles as precursors, e.g., 6K1-CI or CI-6K2, and that the in trans-expressed CI could not be recruited into replication vesicles for replication. In the cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO and expressing PIPO, CI-CFP was located mainly at the cell periphery, with a few inclusions in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3E, frames I to III). Importantly, most cytoplasmic CI inclusions did not associate with 6K2-containing aggregates (Fig. 3E, frame IV). In the cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO and expressing P3N-PIPO, CI was also located mainly at the cell periphery (Fig. 3F, frames I to III). Consistently, cytoplasmic CI inclusions were not associated with 6K2-containing aggregates (Fig. 3F, frame IV). These results suggested that P3N is dispensable for the recruitment of CI to the PD but that it may have an unexpected role in directing CI to 6K2 aggregates.

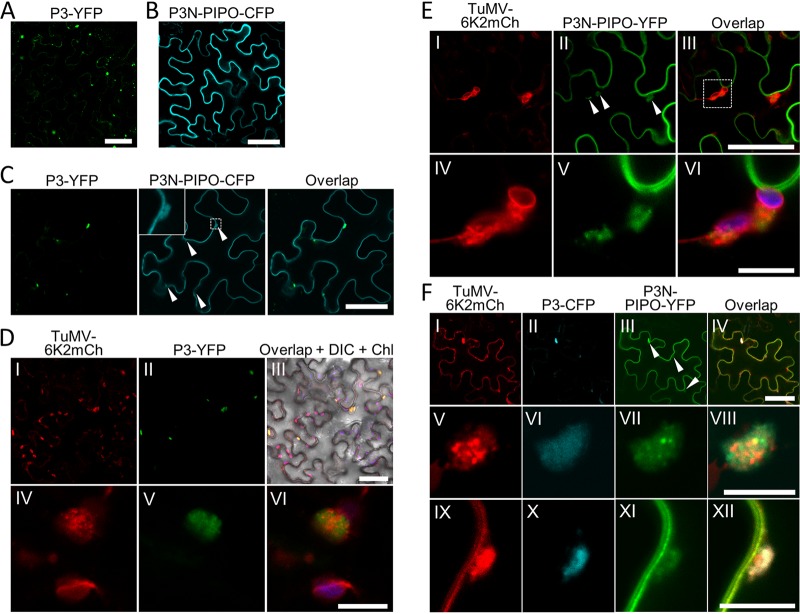

P3N-PIPO is recruited to viral replication complexes (VRCs) by P3.

Transiently expressed P3-YFP localized in the cytoplasm as aggregates with varied sizes (Fig. 4A), whereas transiently expressed P3N-PIPO-CFP localized on the plasma membrane (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, a small portion of P3N-PIPO-CFP was colocalized with P3-YFP when these proteins were coexpressed (Fig. 4C). P3 is a membrane protein involved in viral replication by targeting 6K2 aggregates (13, 35). Thus, P3N-PIPO may also be recruited into 6K2 aggregates by P3 during TuMV infection. Due to the high intensity of the fluorescence signal in previous studies (13, 35), the detailed spatial distribution between P3 and 6K2-induced aggregates has not been revealed. Therefore, N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with TuMV-6K2mCh and P3-YFP. At 60 hpi, the red fluorescence from 6K2-mCherry was observed as irregularly shaped aggregates and small vesicles in the cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh (Fig. 4D, frame I). P3 aggregates colocalized with 6K2-labeled aggregates under low magnification (Fig. 4D, frames II and III). High magnification showed that 6K2 aggregates were located on the surface of P3 aggregates (Fig. 4D, frames IV to VI).

FIG 4.

P3 redirects P3N-PIPO to 6K2-induced aggregates. (A and B) Subcellular localization of transiently expressed P3-YFP (A) and P3N-PIPO-CFP (B) in N. benthamiana epidermal cells at 48 hpi. Scale bars = 50 μm. (C) Colocalization of P3-YFP and P3N-PIPO-CFP in N. benthamiana epidermal cells at 48 hpi. White arrowheads indicate the cytoplasmic P3N-PIPO molecules that are colocalized with P3. The inset in the middle image is the enlargement of the dashed area to show the typical cytoplasmic P3N-PIPO. Scale bars = 50 μm. (D) Localization of P3-YFP in TuMV-6K2mCh-infected N. benthamiana epidermal cells at 60 hpi. The DIC channel and chloroplast fluorescence are included in frame III to show the cell boundaries. Frames IV to VI represent a typical 6K2-P3 aggregate. Scale bars = 50 (frames I to III) and 10 (frame IV to VI) μm. (E) Localization of P3N-PIPO-YFP in TuMV-6K2mCh-infected N. benthamiana epidermal cells at 60 hpi. White arrowheads indicate the cytoplasmic P3N-PIPO molecules that are colocalized with 6K2 aggregates. Frames IV to VI are enlargements of the dashed area in frame III. The chloroplast fluorescence (purple) is included in frame VI. Scale bars = 50 (frames I to III) and 10 (frames IV to VI) μm. (F) Localization of P3-CFP and P3N-PIPO-YFP during the infection of TuMV-6K2mCh in N. benthamiana epidermal cells at 60 hpi. White arrowheads indicate the cytoplasmic P3N-PIPO molecules that are colocalized with P3 and 6K2 aggregates. Frames IV to XII represent typical 6K2-P3N-PIPO-P3 aggregates in the cytoplasm (frames V to VIII) or at the cell periphery (frames IX to XII). Scale bars = 50 (frames I to IV) and 10 (frames V to XII) μm.

The distribution of P3N-PIPO under the condition of TuMV infection was also analyzed with the same strategy. Consistent with previous studies (16, 20), P3N-PIPO-YFP was located mainly on the plasma membrane, which also contained PDs in the cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, fluorescence signals of P3N-PIPO-YFP were also recorded in irregularly 6K2-labeled vesicles or aggregates (Fig. 4E). High magnification revealed that P3N-PIPO was located inside the 6K2-labeled aggregates as a smear signal or granules (Fig. 4E, frames IV to VI). N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with TuMV-6K2mCh, P3-CFP, and P3N-PIPO-YFP to simultaneously analyze the spatial relationships between P3, P3N-PIPO, and 6K2 under the condition of virus infection. Consistently, P3N-PIPO was located mainly at the plasma membrane, and a small portion also colocalized with the 6K2-containing aggregates and P3 aggregates at low magnification (Fig. 4F, frames I to IV). High magnification revealed that the signal of P3N-PIPO largely overlapped with P3 fluorescence in both large and small 6K2-containing aggregates (Fig. 4F, frames V to XII). Taken together, these results suggested that a portion of P3N-PIPO is also located in 6K2-containing aggregates during TuMV replication.

P3 is essential for the recruitment of P3N-PIPO to VRCs.

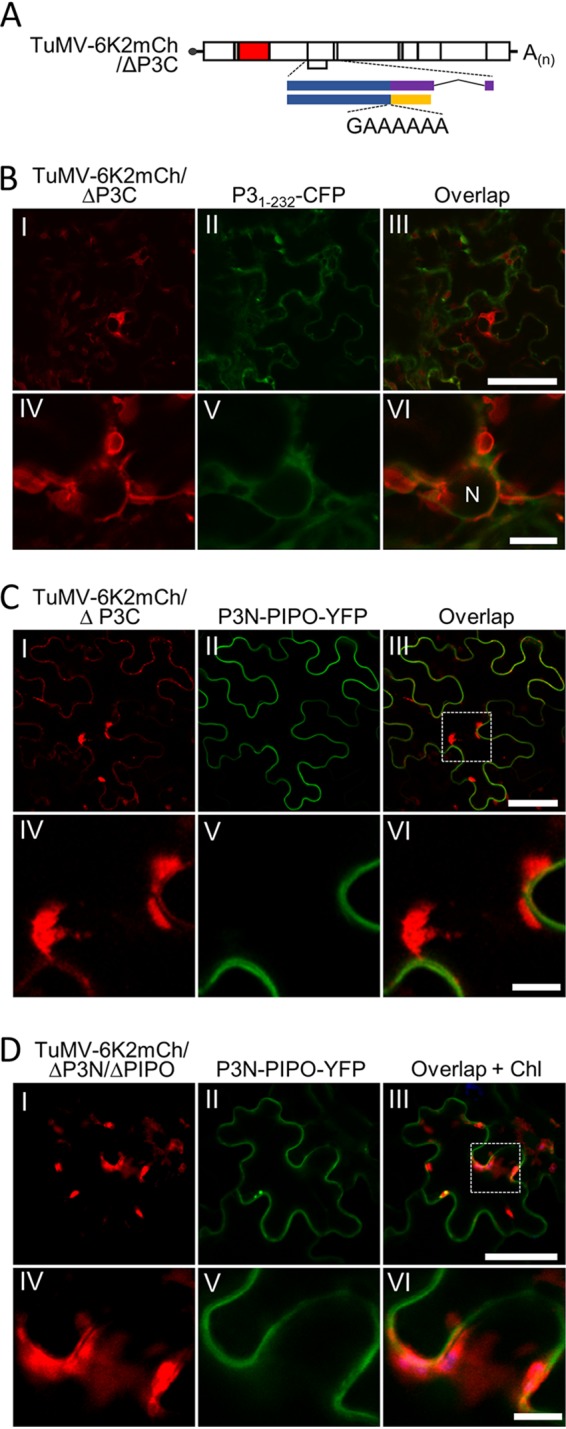

We thus suspected that P3N-PIPO is recruited to 6K2 aggregates via P3, since P3N-PIPO interacts with P3 and deletion of the C-terminal 242 to 347 aa of P3 abolishes the colocalization of P3 with 6K2 (13). A TuMV mutant named TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C was constructed in which the C-terminal aa 232 to 340 of P3 were deleted (Fig. 5A). The coding sequences for the first 9 aa and the last 15 aa of P3C were retained in TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C to maintain the production of P3N-PIPO and efficient cleavage at the P3 and 6K1 junction. In N. benthamiana epidermal cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C and coexpressing P31-232-CFP, the smeared P31-232-CFP fluorescence signal did not colocalize with 6K2-labeled vesicles or aggregates (Fig. 5B, frames II and V), suggesting that deletion of aa 232 to 340 of P3 also abolishes the localization of P3 to 6K2 aggregates. N. benthamiana leaves were then infiltrated with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C and P3N-PIPO-YFP to analyze the spatial distribution of P3N-PIPO and 6K2-induced aggregates. Interestingly, no fluorescence signal of P3N-PIPO-YFP was recorded in the 6K2-labeled aggregates despite the bright fluorescence of P3N-PIPO-YFP on the plasma membrane (Fig. 5C), suggesting that P3N-PIPO relies on P3 to target 6K2 aggregates. To further confirm this possibility, the subcellular localization of P3N-PIPO-YFP in N. benthamiana cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO was also analyzed. Confocal microscopy results showed that P3N-PIPO-YFP also failed to target 6K2-labeled aggregates (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these results suggested that P3N-PIPO is recruited to 6K2 aggregates by P3 via the interaction between the shared P3N domain.

FIG 5.

The recruitment of P3N-PIPO to 6K2-induced aggregates is dependent on P3. (A) Schematic representation of TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C. (B) Localization of P31-232-CFP in TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C-infected N. benthamiana epidermal cells at 60 hpi. N, nucleus. Scale bars = 50 (frames I to III) and 10 (frames IV to VI) μm. (C and D) Localization of P3N-PIPO-YFP during the infection with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C (C) or TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO (D) in N. benthamiana epidermal cells at 60 hpi. The dashed areas in frame III of panels B and C are enlarged in frames IV to VI. Scale bars = 50 (frames I to III) and 10 (frames IV to VI) μm.

Targeting 6K2 aggregates to CI aggregates by P3 and P3N-PIPO.

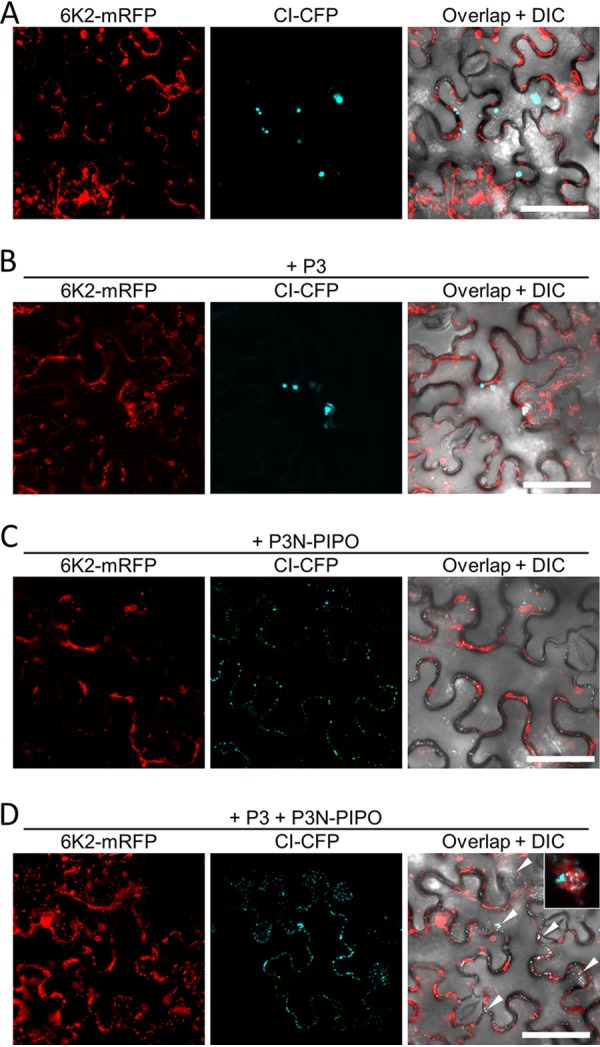

The above-described results strongly suggest that the localization of CI to 6K2 aggregates is bridged by P3N-PIPO and P3, which interact with CI and 6K2, respectively. To confirm this hypothesis, the distribution of CI-CFP and a C-terminal monomer red fluorescent protein (mRFP)-tagged 6K2 (6K2-mRFP) was analyzed in N. benthamiana epidermal cells in the presence of nonfluorescent P3, P3N-PIPO, or both. The CI-CFP inclusions were located exclusively in the cytoplasm and were not associated with 6K2 aggregates in the cells expressing CI-CFP and 6K2-mRFP (Fig. 6A). The addition of P3 had no obvious influence on the distribution of both proteins (Fig. 6B). The addition of P3N-PIPO also did not rescue the association of CI-CFP with 6K2-mRFP aggregates, although CI-CFP was mostly translocated to PDs by P3N-PIPO (Fig. 6C). In the cells expressing all four proteins, cytoplasmic 6K2-labeled vesicles or aggregates that contain CI inclusions were observed (Fig. 6D), and most cell peripheral CI inclusions were also associated with 6K2-labeled vesicles (Fig. 6D). Together, these data suggest that CI is recruited to 6K2 aggregates via P3 and P3N-PIPO.

FIG 6.

Recruitment of CI to 6K2-containing aggregates by P3N-PIPO and P3. (A to D) Subcellular localization of transiently expressed CI-CFP and 6K2-mREP in the absence of other viral proteins (A) or in the presence of P3 (B), P3N-PIPO (C), or P3 and P3N-PIPO (D) in N. benthamiana epidermal cells at 48 hpi. White arrowheads in panel D indicate the cytoplasmic 6K2-labeled vesicles or aggregates that contain CI inclusions. A typical cytoplasmic 6K2-labeled aggregate containing CI inclusions is shown in the inset of panel D. All scale bars = 50 μm.

6K2-induced aggregates localize to the PD.

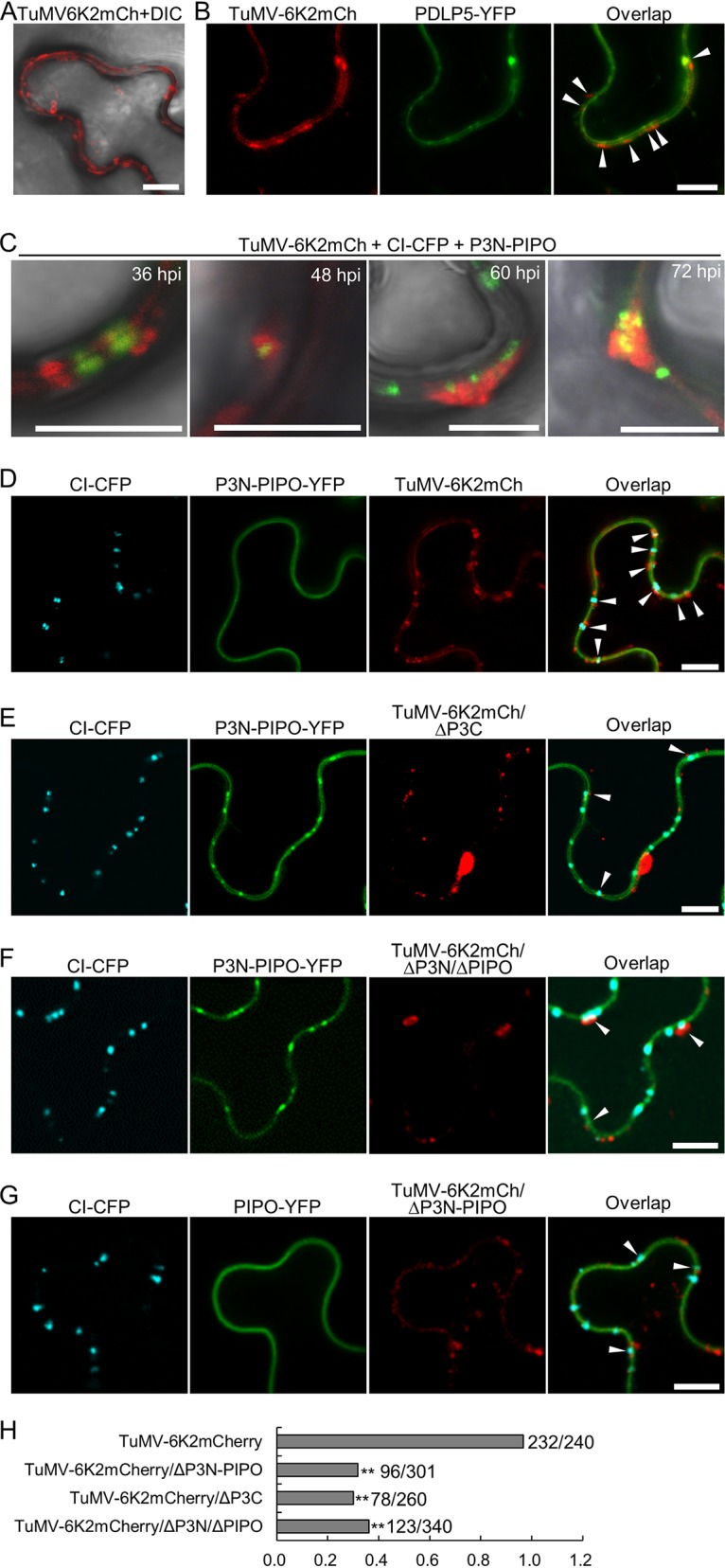

The above-described results imply that the defective movement of TuMV mutants lacking P3N or P3C may be due to the loss of connection between CI and 6K2 vesicles or aggregates, as PD localization of CI is not affected in these mutants. TuMV infection induces a large number of 6K2 vesicles in the cell, and some of them are located at the cell periphery (40, 44). Thus, it is possible that the 6K2 vesicles can be anchored at PDs by the sequential interactions between CI, P3N-PIPO, P3, and 6K2 (27). A large number of peripheral 6K2 vesicles were observed in N. benthamiana cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh (Fig. 7A). Most, if not all, peripheral vesicles were colocalized with C-terminally YFP-tagged plasmodesma-located protein 5 (PDLP5-YFP), suggesting that most peripherally 6K2-induced vesicles are in proximity with PDs (Fig. 7B). Time course analyses revealed PD-located CI inclusions associated with small 6K2 vesicles at the early infection stage, e.g., 36 hpi. As the infection progressed, the 6K2 vesicles gradually grew into aggregates and covered the entire top of the PD-located CI inclusions at the late infection stage (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that the ER-derived 6K2 vesicles are anchored at the PD-located CI inclusions during virus infection.

FIG 7.

Anchoring of 6K2 vesicles at PDs is dependent on P3N-PIPO and P3. (A) Distribution of 6K2 vesicles in the TuMV-6K2mCh-infected N. benthamiana epidermal cell periphery at 60 hpi. The DIC channels are included to show cell outlines. Scale bars = 10 μm. (B) Subcellular localization of peripheral 6K2 vesicles and PDLP5-YFP in TuMV-6K2mCh-infected N. benthamiana epidermal cells. Micrographs were taken at 60 hpi. White arrowheads indicate PDLP5-labeled PDs that associated with 6K2 vesicles. All scale bars = 10 μm. (C) Accumulation of 6K2 aggregates at PD-located CI inclusions at different time points during TuMV infection. At an early infection stage (36 hpi), only small 6K2 vesicles were found to be associated with PD-located CI inclusions, which gradually expanded into large irregularly shaped aggregations from 48 to 72 hpi. Scale bars = 10 μm. (D to G) Distribution of 6K2-induced vesicles at PD-located CI inclusions in N. benthamiana epidermal cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh (D), TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C (E), TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO (F), or TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO (G). The 6K2-labeled vesicles in proximity to the PD-located CI inclusions are indicated by white arrowheads. Micrographs were taken at 60 hpi. Scale bars = 10 μm. (H) Statistical analyses of the percentage of PD-located CI associated with 6K2-labeled vesicles in TuMV-6K2mCh-, TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C-, TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO-, and TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO-infected N. benthamiana epidermal cells. The numbers at the right indicate the number of conical CI inclusions associated with 6K2 vesicles per the total number of CI inclusions analyzed. **, P < 0.01 (Student’s t test).

The relationship between 6K2 vesicles and PD-located CI inclusions was analyzed in N. benthamiana epidermal cells infected with either wild-type TuMV-6K2mCh, TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C, TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C/ΔPIPO, or TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO. In this experiment, CI-CFP and P3N-PIPO-YFP were coexpressed with wild-type TuMV-6K2mCh, TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C, or TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C/ΔPIPO, whereas CI-CFP and PIPO-YFP were coexpressed with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO. In the cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh, most of the PD-located CI inclusions (232 out of 240) were associated with 6K2-containing vesicles (Fig. 7D and H). However, only a few PD-located CI inclusions (78 out of 260) were associated with 6K2-containing vesicles in N. benthamiana epidermal cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C (Fig. 7E and H), suggesting that disrupting the interaction between P3 and 6K2 results in the loss of 6K2 vesicles on PD-located CI inclusions. Consistently, only a small part of the PD-located CI inclusions were associated with 6K2-labeled vesicles in the cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO (123 out of 340) or TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO (96 out of 301) (Fig. 7F to H), suggesting that the interaction between P3 and P3N-PIPO is also required for anchoring 6K2 vesicles on PD-located CI inclusions.

DISCUSSION

P3N-PIPO is the only dedicated movement protein encoded by potyviruses (10, 14). Previous studies showed that P3N-PIPO interacts with CI and PCaP1 via the PIPO domain and directs CI to the PD to form conical structures extending through the PD (15, 16, 20). In this study, we found that P3N-PIPO interacts with P3 via the shared P3N domain (Fig. 1). Intriguingly, we found that the P3N of either P3N-PIPO or P3 is also indispensable for TuMV cell-to-cell movement (Fig. 2). Thus, P3N-PIPO functions in potyviral cell-to-cell movement by interacting with CI and PCaP1 via the PIPO domain and with P3 via the shared P3N domain. Previous studies showed that P3C is responsible for the localization of P3 to 6K2 vesicles, which is critical for both viral replication and intercellular movement (13, 35). Remarkably, knockout of the P3N domain of P3 had no obvious influence on virus replication (Fig. 2D and E). Therefore, P3N of P3 is primarily involved in viral movement by interacting with P3N-PIPO. However, how P3 coordinates cell-to-cell movement and replication still needs to be investigated in the future.

Transiently expressed P3 is able to recruit a portion of P3N-PIPO to the cytoplasmic aggregates it has formed (Fig. 4C), and the complexes formed by P3 and P3N-PIPO are located inside the 6K2-containing aggregates during virus infection (Fig. 4F). Moreover, deletion of either P3N or P3C of P3 causes the loss of P3N-PIPO in 6K2-containing aggregates (Fig. 5C and D). These results indicate that one important function of the interaction between P3 and P3N-PIPO is to create a direct connection between P3N-PIPO and 6K2 aggregates. Interestingly, knockout of the P3N of either P3 or P3N-PIPO did not affect the localization of CI to PDs (Fig. 3); instead, it caused the loss of CI inclusions in the 6K2-induced aggregates (Fig. 3E and F). Thus, the interaction between P3 and P3N-PIPO also allows the virus to establish the connection between CI inclusions and 6K2 aggregates. Indeed, transient expression of CI, P3N-PIPO, P3, and 6K2 is able to reestablish the 6K2 aggregates that contain CI inclusions resembling those observed during virus infection (Fig. 3D and 6D). In a previous immune-electron microscopy study, PD-located CI inclusions associated with P3 during TVMV infection were also noted (45). Truly, disruption of the interaction between P3N-PIPO and P3 by deleting P3N or the interaction between P3 and 6K2 by deleting the P3C domain caused a reduction in 6K2 vesicles at PD-located CI inclusions (Fig. 7E to G). Given that TuMV mutants lacking P3N (Fig. 2), P3C (13), or PIPO (20) are also defective in the intercellular movement of potyviruses, it is possible that anchoring the replicative 6K2 vesicles or aggregates to the PD-located CI inclusions via the sequential interactions between CI, P3N-PIPO, 6K2, and P3 is a critical step in cell-to-cell movement. 6K2 vesicles can move between cells and enter into the extracellular space by exocytosis (46, 47). It will be interesting to investigate the role of these multipartite interactions among 6K2, P3, P3N-PIPO, and CI in this process. Noticeably, a small portion of 6K2 vesicles was still in proximity to PD-located, conical CI inclusions in the cells infected with TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C, TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO, or TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO (Fig. 7E to G). However, no cell-to-cell movement of these TuMV mutants was detected (Fig. 2B and C). A recent study also found that a TuMV mutant lacking part of the P3 C-terminal domain was defective in both replication and cell-to-cell movement (13). Thus, it is possible that these vesicles are not anchored at PD-located CI inclusions per se; as a result, the cargoes (virions or CP-containing RNPs) were still not accessible to PD-located, conical CI inclusions. Alternatively, the interaction between P3N-PIPO and P3 is required not only for anchoring 6K2 vesicles to PD-located CI inclusions but also for other infection steps, e.g., genome release and/or encapsulation.

It is believed that the replication and cell-to-cell movement of positive-stranded RNA viruses are tightly coupled. For instance, PVX forms mini-VRCs at the entrance of PDs for efficient cell-to-cell movement (48), and the MP of Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) is able to recruit cytoplasmic VRCs to PDs and subsequently transport them through PDs into neighboring cells (49). Based on our results, this phenomenon is also the case for TuMV and possibly other potyviruses. One interesting question is why localization of 6K2 vesicles to PD-located CI inclusions is the prerequisite step for successful cell-to-cell movement. CI has a nonspecific RNA binding activity (50); thus, it cannot distinguish viral genomic RNAs or cellular mRNAs and the free form of CPs or those containing viral RNA. Obviously, localization of the viral replication complex at PDs not only allows an increase in the concentration of viral RNA or virions at the entrance of the PD but also excludes cellular mRNA, which can simultaneously increase the specificity and efficiency of transport.

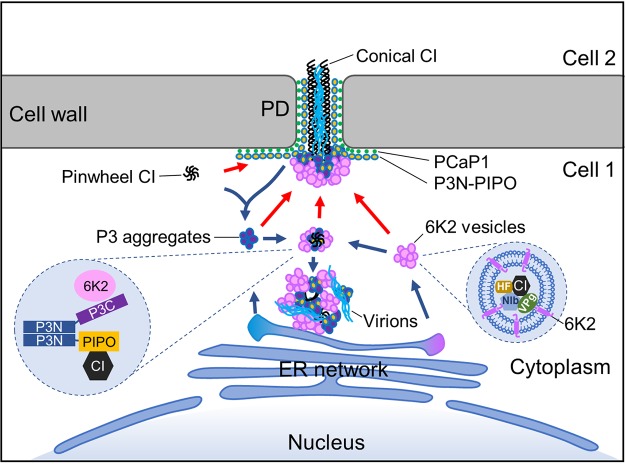

In conclusion, our results revealed the multipartite interactions among 6K2, P3, P3N-PIPO, and CI, which not only are required for establishing perinuclear virus-induced complexes but also are essential for successful cell-to-cell movement. Based on previous studies and these results, a new model for potyviral cell-to-cell movement is therefore proposed (Fig. 8). After entrance and protein translation, replication-associated viral and host proteins are assembled into viral replication complexes in 6K2 vesicles, which can further cluster into aggregates. ER-derived P3 aggregates are recruited to 6K2 aggregates by the interaction between the P3C domain and 6K2. P3N-PIPO localizes to the plasma membrane and PD, and a small portion of P3N-PIPO is also recruited by P3 to the 6K2 aggregates. PCaP1-associated P3N-PIPO recruits CI to the PD, whereas P3-colocalized P3N-PIPO recruits CI to the 6K2 aggregates. Then, additional CI molecules bind to the CI/P3N-PIPO complex via CI self-interaction to form conical structures at the PD or pinwheel structures in the cytoplasm. Notably, CI molecules are also recruited into 6K2 vesicles for replication. However, the connections or independence of the CI molecules participating cell-to-cell and replication is not known at present. Cytoplasmic 6K2 aggregates cluster together with P3, P3N-PIPO, and CI at the perinuclear area to form typical virus-induced irregular viroplasm or are delivered to the PD and anchored at the conical CI inclusions. At the PD, newly synthesized viral genomic RNAs are fully or partially encapsidated by CP into virions or RNP complexes and are then trafficked by CI to neighboring cells.

FIG 8.

Schematic model of the cell-to-cell movement of TuMV. CI, P3N-PIPO, P3, 6K2, virions, PCaP1, VPg, NIb, and host factor (HF) are depicted in black pinwheels or hexagons, yellow spheres with blue margins, purple spheres with blue margins, pink spheres or cylinder, cyan lines, green dots, a dark green oval, a blue pentagon, and a yellow podetium, respectively. The red and dark blue arrows indicate the possible routes for assembling PD-located and cytoplasmic virus-induced CI/P3N-PIPO/P3/6K2 complexes, respectively. The two dashed areas show the interaction network between 6K2, P3, P3N-PIPO, and CI and a typical replicative 6K2 vesicle, respectively. The nucleus, cytoplasm, cell wall, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) network, and PD are also indicated. Note that all elements are not drawn in scale.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant growth conditions and virus inoculation.

N. benthamiana seedlings were grown in pots in a plant growth chamber under a 16-h/8-h (light/dark) photoperiod and 60% humidity at 23°C. Agroinfiltrations were performed as previously described (36, 51). In detail, overnight cultures of agrobacteria harboring the proper plasmids were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 1 min at room temperature, washed twice in infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, pH 5.6; 10 mM MgCl; 100 μM acetosyringone), and then resuspended in infiltration buffer. The agrobacteria were used to infiltrate 3-week-old N. benthamiana leaves using a 1-ml needleless syringe at an OD600 of 0.1 or as otherwise indicated.

Vector construction.

The full coding sequences of P1, HcPro, P3N-PIPO, P3, 6K1, CI, 6K2, VPg, Pro, NIb, and CP and the coding sequences of the P3N, PIPO, and P3C domains were amplified from TuMV-GFP (40) by using Phanta Super Fidelity DNA polymerase (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) and inserted into the entry vector pDONR221 or pDONR207 (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China) by BP Clonase (Invitrogen). The polymerase slippage sites (5′-GAAAAAA-3′) in pDONR221-P3N-PIPO and pDONR221-P3 were mutated into 5′-GAGAAGAA-3′ and 5′-GAGAAGA-3′, respectively, to avoid the possible expression of truncated P3 or P3N-PIPO. The entry clones were recombined into various Gateway vectors using LR Clonase enzyme mix (Invitrogen). pEarleyGate-101 and -102 (52) and pGWB554 (53) were used to produce C-terminally YFP-, CFP-, or mRFP-tagged fusion constructs; p35S-YN gateway, p35S-YC gateway, p35S-gateway YN, and p35S-gateway YC (54) were used to construct N- or C- terminally YN- and YC-fused constructs for BiFC assay; and pBT3N-GW and pPR3C-GW (36) were used to construct N-terminally LexA-Cub- or C-terminally Nub-tagged constructs for the MYTH assay.

The TuMV mutants, e.g., TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO, TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO, TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO, and TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C, were constructed by yeast homologous recombination using the yeast-Escherichia coli-Agrobacterium shuttle vector pCB301-2μ-HDV as described previously (55). The polymerase slippage site was mutated to 5′-GAGAAGA-3′ in TuMV-GFP/ΔP3N-PIPO and TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO, and the region encoding aa 5 to 152 of the P3N domain in TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N/ΔPIPO was deleted using TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3N-PIPO as the template. TuMV-6K2mCh/ΔP3C was constructed by the deletion of the region encoding aa 232 to 340 of P3 in TuMV-6K2mCh. All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

Confocal microscopy.

Confocal microscopy analysis was performed as described previously (36, 55). A 0.5- by 0.5-cm leaf patch was excised from the infiltrated leaf area and was monitored with a Leica TCS SP8 confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Germany) or Nikon A1 HD25 confocal microscope (Nikon, Japan) at the desired time point. The excitation laser wavelengths for CFP, YFP, and mRFP (or mCherry) were 405, 514, and 568 nm, respectively. The emission bandwidths of 425 to 475 nm (for CFP), 520 to 550 nm (for YFP), and 570 to 620 nm (for mRFP) were collected. The sequential mode was used when multiple fluorescence signals needed to be recorded to avoid signal cross-contamination, and each fluorescence signal was further confirmed separately.

MYTH assay.

The membrane yeast two hybrid (MYTH) assay was performed as described previously (36). In brief, plasmids were introduced into the yeast strain NMY51 using a Super Yeast Transformation kit II (Coolaber Biotech, Beijing, China) according to the provided protocol. Transformed yeast cells were plated onto synthetic defined (SD) medium lacking tryptophan and leucine (−WL) and cultured for 2 days at 30°C. Several independent positive transformants were transferred to high-stringency selection plates lacking tryptophan, leucine, histidine, and adenine (−WLHA) and incubated at 30°C for 3 to 4 days.

Western blotting.

Western blotting was performed as described previously (51, 56). A rabbit anti-Myc tag antibody (catalog number ab9106; Abcam, Shanghai, China) was used to detect FLAG-4×Myc-tagged recombinant proteins at a 1:5,000 dilution. The membranes were visualized with Immobilon Western chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase (HRP) substrate (Millipore, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In each experiment, a parallel gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 as a loading control.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from N. benthamiana leaf tissues using an RNAprep plant kit (Transgen, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA of N. benthamiana protoplasts was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the provided protocol. We used 500 μg (leaf tissue) or 200 μg (protoplasts) of DNA-free total RNA for first-strand cDNA synthesis using Superscript IV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with an oligo(dT)12-18 primer. For analyzing TuMV mutants, the entire coding region of P3 was amplified and inserted into the pEASY-Blunt vector (Transgen). At least 4 independent clones of each fragment were verified by DNA sequencing. qRT-PCR was performed as described previously (36). In brief, qRT-PCR was performed in a 20-μl volume system containing 4 μl of 10-fold-diluted cDNA, a 5 μM concentration of each primer, and 1× SYBR green master mix (Vazyme) on a LightCycler 480 real-time PCR system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The genomic RNA of TuMV was determined by amplification of a 257-bp fragment of the TuMV CP gene, and the N. benthamiana actin gene (NbActin; GenBank accession no. AY179605) was used as an internal control. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Bioinformatic analyses.

The secondary structures of P3 and P3N-PIPO were predicted using Jpred 4 (57) with default settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671998), the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (ZD2018002 and LH2019C027), and the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Scholars of the Department of Education of Heilongjiang (2018QD0002).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sieczkarski SB, Whittaker GR. 2002. Dissecting virus entry via endocytosis. J Gen Virol 83:1535–1545. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-7-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoelz JE, Harries PA, Nelson RS. 2011. Intracellular transport of plant viruses: finding the door out of the cell. Mol Plant 4:813–831. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar D, Kumar R, Hyun TK, Kim JY. 2015. Cell-to-cell movement of viruses via plasmodesmata. J Plant Res 128:37–47. doi: 10.1007/s10265-014-0683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinlein M. 2015. Plant virus replication and movement. Virology 479-480:657–671. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu C, Nelson RS. 2013. The cell biology of Tobacco mosaic virus replication and movement. Front Plant Sci 4:12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solovyev A, Kalinina N, Morozov S. 2012. Recent advances in research of plant virus movement mediated by triple gene block. Front Plant Sci 3:276. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wylie SJ, Adams M, Chalam C, Kreuze J, López-Moya JJ, Ohshima K, Praveen S, Rabenstein F, Stenger D, Wang A, Zerbini FM, ICTV Report Consortium . 2017. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Potyviridae. J Gen Virol 98:352–354. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Revers F, García JA. 2015. Molecular biology of potyviruses. Adv Virus Res 92:101–199. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urcuqui-Inchima S, Haenni A-L, Bernardi F. 2001. Potyvirus proteins: a wealth of functions. Virus Res 74:157–175. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(01)00220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung BY, Miller WA, Atkins JF, Firth AE. 2008. An overlapping essential gene in the Potyviridae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:5897–5902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800468105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olspert A, Chung BY, Atkins JF, Carr JP, Firth AE. 2015. Transcriptional slippage in the positive-sense RNA virus family Potyviridae. EMBO Rep 16:995–1004. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodamilans B, Valli A, Mingot A, San León D, Baulcombe D, López-Moya JJ, García JA. 2015. RNA polymerase slippage as a mechanism for the production of frameshift gene products in plant viruses of the Potyviridae family. J Virol 89:6965–6967. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00337-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui X, Yaghmaiean H, Wu G, Wu X, Chen X, Thorn G, Wang A. 2017. The C-terminal region of the Turnip mosaic virus P3 protein is essential for viral infection via targeting P3 to the viral replication complex. Virology 510:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wen RH, Hajimorad MR. 2010. Mutational analysis of the putative pipo of Soybean mosaic virus suggests disruption of PIPO protein impedes movement. Virology 400:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vijayapalani P, Maeshima M, Nagasaki-Takekuchi N, Miller WA. 2012. Interaction of the trans-frame potyvirus protein P3N-PIPO with host protein PCaP1 facilitates potyvirus movement. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002639. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei T, Zhang C, Hong J, Xiong R, Kasschau KD, Zhou X, Carrington JC, Wang A. 2010. Formation of complexes at plasmodesmata for potyvirus intercellular movement is mediated by the viral protein P3N-PIPO. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000962. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng G, Yang Z, Zhang H, Zhang J, Xu J. 2019. Remorin interacting with PCaP1 impairs Turnip mosaic virus intercellular movement but is antagonized by VPg. New Phytol 225:2122–2139. doi: 10.1111/nph.16285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song P, Zhi H, Wu B, Cui X, Chen X. 2016. Soybean Golgi SNARE 12 protein interacts with Soybean mosaic virus encoded P3N-PIPO protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 478:1503–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song P, Chen X, Wu B, Gao L, Zhi H, Cui X. 2016. Identification for soybean host factors interacting with P3N-PIPO protein of Soybean mosaic virus. Acta Physiol Plant 38:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11738-016-2126-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng G, Dong M, Xu Q, Peng L, Yang Z, Wei T, Xu J. 2017. Dissecting the molecular mechanism of the subcellular localization and cell-to-cell movement of the Sugarcane mosaic virus P3N-PIPO. Sci Rep 7:9868. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10497-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo JK, Vo Phan MS, Kang SH, Choi HS, Kim KH. 2013. The charged residues in the surface-exposed C-terminus of the Soybean mosaic virus coat protein are critical for cell-to-cell movement. Virology 446:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolja VV, Haldeman-Cahill R, Montgomery AE, Vandenbosch KA, Carrington JC. 1995. Capsid protein determinants involved in cell-to-cell and long distance movement of Tobacco etch potyvirus. Virology 206:1007–1016. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts IM, Wang D, Findlay K, Maule AJ. 1998. Ultrastructural and temporal observations of the potyvirus cylindrical inclusions (CIs) show that the Cl protein acts transiently in aiding virus movement. Virology 245:173–181. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez-Cerezo E, Findlay K, Shaw JG, Lomonossoff GP, Qiu SG, Linstead P, Shanks M, Risco C. 1997. The coat and cylindrical inclusion proteins of a potyvirus are associated with connections between plant cells. Virology 236:296–306. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaad MC, Jensen PE, Carrington JC. 1997. Formation of plant RNA virus replication complexes on membranes: role of an endoplasmic reticulum-targeted viral protein. EMBO J 16:4049–4059. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei T, Wang A. 2008. Biogenesis of cytoplasmic membranous vesicles for plant potyvirus replication occurs at endoplasmic reticulum exit sites in a COPI- and COPII-dependent manner. J Virol 82:12252–12264. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01329-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Movahed N, Patarroyo C, Sun J, Vali H, Laliberté J-F, Zheng H. 2017. Cytoplasmic inclusion of Turnip mosaic virus serves as a docking point for the intercellular movement of viral replication vesicles. Plant Physiol 175:1732–1744. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosque G, Folch-Fortuny A, Picó J, Ferrer A, Elena SF. 2014. Topology analysis and visualization of potyvirus protein-protein interaction network. BMC Syst Biol 8:129–115. doi: 10.1186/s12918-014-0129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo D, Rajamäki ML, Saarma M, Valkonen JP. 2001. Towards a protein interaction map of potyviruses: protein interaction matrixes of two potyviruses based on the yeast two-hybrid system. J Gen Virol 82:935–939. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-4-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen WT, Wang MQ, Yan P, Gao L, Zhou P. 2010. Protein interaction matrix of Papaya ringspot virus type P based on a yeast two-hybrid system. Acta Virol 54:49–54. doi: 10.4149/av_2010_01_49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin L, Shi Y, Luo Z, Lu Y, Zheng H, Yan F, Chen J, Chen J, Adams MJ, Wu Y. 2009. Protein-protein interactions in two potyviruses using the yeast two-hybrid system. Virus Res 142:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang SH, Lim WS, Kim KH. 2004. A protein interaction map of Soybean mosaic virus strain G7H based on the yeast two-hybrid system. Mol Cells 18:122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zilian E, Maiss E. 2011. Detection of plum pox potyviral protein-protein interactions in planta using an optimized mRFP-based bimolecular fluorescence complementation system. J Gen Virol 92:2711–2723. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.033811-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenner CE, Wang X, Tomimura K, Ohshima K, Ponz F, Walsh JA. 2003. The dual role of the potyvirus P3 protein of Turnip mosaic virus as a symptom and avirulence determinant in brassicas. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 16:777–784. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.9.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui X, Wei T, Chowda-Reddy RV, Sun G, Wang A. 2010. The Tobacco etch virus P3 protein forms mobile inclusions via the early secretory pathway and traffics along actin microfilaments. Virology 397:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu X, Liu J, Chai M, Wang J, Li D, Wang A, Cheng X. 2018. The Potato virus X TGBp2 protein plays dual functional roles in viral replication and movement. J Virol 93:e01635-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01635-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishnamurthy K, Heppler M, Mitra R, Blancaflor E, Payton M, Nelson RS, Verchot-Lubicz J. 2003. The Potato virus X TGBp3 protein associates with the ER network for virus cell-to-cell movement. Virology 309:135–151. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samuels TD, Ju HJ, Ye CM, Motes CM, Blancaflor EB, Verchot-Lubicz J. 2007. Subcellular targeting and interactions among the Potato virus X TGB proteins. Virology 367:375–389. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yaghmaiean H. 2015. Functional characterization of P3N-PIPO protein in the potyviral life cycle. University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cotton S, Grangeon R, Thivierge K, Mathieu I, Ide C, Wei T, Wang A, Laliberté J-F. 2009. Turnip mosaic virus RNA replication complex vesicles are mobile, align with microfilaments, and are each derived from a single viral genome. J Virol 83:10460–10471. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00819-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernández A, Guo HS, Sáenz P, Simón-Buela L, Gómez de Cedrón M, García JA. 1997. The motif V of Plum pox potyvirus CI RNA helicase is involved in NTP hydrolysis and is essential for virus RNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res 25:4474–4480. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng P, Wu Z, Wang A. 2015. The multifunctional protein CI of potyviruses plays interlinked and distinct roles in viral genome replication and intercellular movement. Virol J 12:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0369-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gómez de Cedrón M, Osaba L, López L, García JA. 2006. Genetic analysis of the function of the Plum pox virus CI RNA helicase in virus movement. Virus Res 116:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng X, Deng P, Cui H, Wang A. 2015. Visualizing double-stranded RNA distribution and dynamics in living cells by dsRNA binding-dependent fluorescence complementation. Virology 485:439–451. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodríguez-Cerezo E, Ammar ED, Pirone TP, Shaw JG. 1993. Association of the non-structural P3 viral protein with cylindrical inclusions in potyvirus-infected cells. J Gen Virol 74:1945–1949. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-9-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Movahed N, Cabanillas DG, Wan J, Vali H, Laliberté J-F, Zheng H. 2019. Turnip mosaic virus components are released into the extracellular space by vesicles in infected leaves. Plant Physiol 180:1375–1388. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grangeon R, Jiang J, Wan J, Agbeci M, Zheng H, Laliberté J-F. 2013. 6K2-induced vesicles can move cell to cell during Turnip mosaic virus infection. Front Microbiol 4:351. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tilsner J, Linnik O, Louveaux M, Roberts IM, Chapman SN, Oparka KJ. 2013. Replication and trafficking of a plant virus are coupled at the entrances of plasmodesmata. J Cell Biol 201:981–995. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawakami S, Watanabe Y, Beachy RN. 2004. Tobacco mosaic virus infection spreads cell to cell as intact replication complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:6291–6296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401221101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernández A, García JA. 1996. The RNA helicase CI from Plum pox potyvirus has two regions involved in binding to RNA. FEBS Lett 388:206–210. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheng X, Xiong R, Li Y, Li F, Zhou X, Wang A. 2017. Sumoylation of Turnip mosaic virus RNA polymerase promotes viral infection by counteracting the host NPR1-mediated immune response. Plant Cell 29:508–525. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Earley KW, Haag JR, Pontes O, Opper K, Juehne T, Song K, Pikaard CS. 2006. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J 45:616–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakagawa T, Kurose T, Hino T, Tanaka K, Kawamukai M, Niwa Y, Toyooka K, Matsuoka K, Jinbo T, Kimura T. 2007. Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J Biosci Bioeng 104:34–41. doi: 10.1263/jbb.104.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu Q, Tang X, Tian G, Wang F, Liu K, Nguyen V, Kohalmi SE, Keller WA, Tsang EWT, Harada JJ, Rothstein SJ, Cui Y. 2010. Arabidopsis homolog of the yeast TREX-2 mRNA export complex: components and anchoring nucleoporin. Plant J 61:259–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun K, Zhao D, Liu Y, Huang C, Zhang W, Li Z. 2017. Rapid construction of complex plant RNA virus infectious cDNA clones for agroinfection using a yeast-E. coli-Agrobacterium shuttle vector. Viruses 9:332. doi: 10.3390/v9110332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheng X, Wang A. 2017. The potyviral silencing suppressor protein VPg mediates degradation of SGS3 via ubiquitination and autophagy pathways. J Virol 91:e01478-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01478-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drozdetskiy A, Cole C, Procter J, Barton GJ. 2015. Jpred 4: a protein secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res 43:W389–W394. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]