HTLV-1 is considered the most potent human oncovirus and is also responsible for severe inflammatory disorders. HTLV-1 transcription is undertaken by RNA polymerase II and is controlled by the viral oncoprotein Tax. Tax transactivates the viral promoter first via the recruitment of CREB and its cofactors to the long terminal repeat (LTR). However, how Tax controls subsequent steps of the transcription process remains unclear. In this study, we explore the link between Tax and the XPB subunit of TFIIH that governs, via its ATPase activity, the promoter-opening step of transcription. We demonstrate that XPB is a novel physical and functional partner of Tax, recruited on HTLV-1 LTR, and required for viral transcription. These findings extend the mechanism of Tax transactivation to the recruitment of TFIIH and reinforce the link between XPB and transactivator-induced viral transcription.

KEYWORDS: retrovirus, oncoprotein, transcription, TFIIH, promoter opening

ABSTRACT

Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) Tax oncoprotein is required for viral gene expression. Tax transactivates the viral promoter by recruiting specific transcription factors but also by interfering with general transcription factors involved in the preinitiation step, such as TFIIA and TFIID. However, data are lacking regarding Tax interplay with TFIIH, which intervenes during the last step of preinitiation. We previously reported that XPB, the TFIIH subunit responsible for promoter opening and promoter escape, is required for Tat-induced human-immunodeficiency virus promoter transactivation. Here, we investigated whether XPB may also play a role in HTLV-1 transcription. We report that Tax and XPB directly interact in vitro and that endogenous XPB produced by HTLV-1-infected T cells binds to Tax and is recruited on proviral LTRs. In contrast, XPB recruitment at the LTR is not detected in Tax-negative HTLV-1-infected T cells and is strongly reduced when Tax-induced HTLV-1 LTR transactivation is blocked. XPB overexpression does not affect basal HTLV-1 promoter activation but enhances Tax-mediated transactivation in T cells. Conversely, downregulating XPB strongly reduces Tax-mediated transactivation. Importantly, spironolactone (SP)-mediated inhibition of LTR activation can be rescued by overexpressing XPB but not XPD, another TFIIH subunit. Furthermore, an XPB mutant defective for the ATPase activity responsible for promoter opening does not show rescue of the effect of SP. Finally, XPB downregulation reduces viability of Tax-positive but not Tax-negative HTLV-1-transformed T cell lines. These findings reveal that XPB is a novel cellular cofactor hijacked by Tax to facilitate HTLV-1 transcription.

IMPORTANCE HTLV-1 is considered the most potent human oncovirus and is also responsible for severe inflammatory disorders. HTLV-1 transcription is undertaken by RNA polymerase II and is controlled by the viral oncoprotein Tax. Tax transactivates the viral promoter first via the recruitment of CREB and its cofactors to the long terminal repeat (LTR). However, how Tax controls subsequent steps of the transcription process remains unclear. In this study, we explore the link between Tax and the XPB subunit of TFIIH that governs, via its ATPase activity, the promoter-opening step of transcription. We demonstrate that XPB is a novel physical and functional partner of Tax, recruited on HTLV-1 LTR, and required for viral transcription. These findings extend the mechanism of Tax transactivation to the recruitment of TFIIH and reinforce the link between XPB and transactivator-induced viral transcription.

INTRODUCTION

Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is the etiologic agent of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL), a very aggressive malignant proliferation of CD4+ T lymphocytes (1, 2). In addition, HTLV-1 is associated with various inflammatory disorders, notably HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) (3).

The HTLV-1 genome encodes structural, enzymatic, regulatory, and auxiliary proteins. Among them, the regulatory protein Tax is a major player for disease development (4, 5). Indeed, Tax is an oncoprotein able to induce leukemia or lymphoma in transgenic mice (6) as well as immortalization of primary human CD4+ T cells in vitro (7). Tax is also the transactivator of the viral promoter located in the 5′ LTR, thereby controlling its own production as well as that of all sense HTLV-1 transcripts (8).

Transcription is an ordered process that proceeds through multiple stages, including binding of specific transcription factors to the promoter, assembly of the preinitiation complex (PIC), promoter opening and escape, RNA polymerase II (Pol II) pausing, elongation, and termination (reviewed in references 9 and 10). Tax controls the first step by recruiting the specific transcription factor CREB as well as transcription cofactors such as CPB/p300 at viral CREB-response elements (vCRE) located in the U3 region of the 5′ LTR (8, 11). This event was initially believed to be the only mechanism by which Tax achieved maximal transcription. However, further data pointed toward additional key roles of Tax on the subsequent steps of transcription (12). Indeed, Tax was also shown to recruit to the LTR the general transcription factors (GTF) TFIIA and TFIID (TBP and TAF28) (13–15), involved in PIC assembly, as well as the elongation factor pTEF-b (16, 17). TFIIH, which ensures transition between preinitiation and elongation, was also suggested to be required for LTR transactivation by Tax in an in vitro system (15). However, whether TFIIH subunits interact with Tax and/or are required for viral transcription in HTLV-1-infected T cells remains to be investigated.

TFIIH is a complex playing a dual role in DNA repair and transcription. It consists of five nonenzymatic proteins, the CDK-activating kinase (CAK) (cyclin H, CDK7, and Mat1), and the XPD and XPB enzymes (18). Within TFIIH, the ATPase and translocase xeroderma pigmentosum type B (XPB) plays a key role in transcription (19). XPB acts as a molecular wrench able to melt double-stranded DNA, allowing opening and insertion of the sequence around the transcription start into the active site of Pol II (19–22). The ATPase activity of XPB is critical for the DNA opening while the translocase activity is committed to promoter escape (23–25). The ATPase activity of XPB is carried out by the helicase domain 1 motif I and is regulated by other regions of the protein, notably the helicase domain 1 R-E-D motif (24, 26, 27).

XPB plays a complex role in transcription that has only been clarified recently. Indeed, Alekseev et al. demonstrated that XPB causes a regulatory block during preinitiation, imposed by its translocase/helicase activity, then subsequently relieved by its own ATPase activity (21, 28). Strikingly, this mechanism appears to be dispensable for basal transcription while, in contrast, transcription induced by transretinoic acid or cytokines was shown to be sensitive to XPB downregulation (29, 30). This elucidation of XPB function has been greatly facilitated by the use of a drug, spironolactone (SP), originally described as an aldosterone antagonist and later identified as a compound able to induce rapid degradation of XPB (30). Of note, the ability to induce XPB degradation is not related to aldosterone signaling, since the SP derivative eplerenone (EPL) antagonizes aldosterone signaling like SP but has no impact on XPB (30). Strikingly, SP is believed to induce the degradation of XPB within preformed TFIIH complexes, removing XPB while preserving TFIIH integrity (21, 30). A recent study showing that SP-induced XPB degradation depends on its prior phosphorylation by the other TFIIH subunit CDK7 provides the molecular explanation for this selectivity (31).

In a previous study, we demonstrated that XPB is required for Tat-mediated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) promoter activation (32). This prompted us to investigate the possibility that XPB could also contribute to HTLV-1 transcription. In this study, we investigated the potential interaction between Tax and XPB as well as the impact of XPB on HTLV-1 promoter transactivation and viral transcription.

RESULTS

XPB binds to Tax.

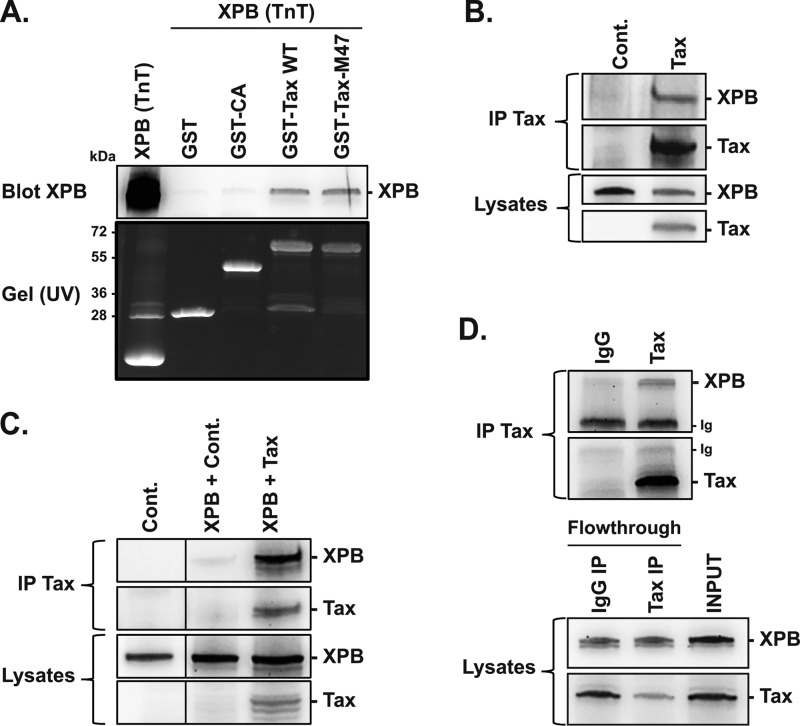

Since Tax was previously shown to interact directly with certain GTFs (13–15), we performed glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assays to examine whether it may also interact directly with XPB. GST and GST-Tax proteins purified from bacterial extracts were incubated with recombinant XPB produced by in vitro transcription/translation (TnT). A GST protein fused to the HIV-1 capsid protein CAp24 (GST-CA) was also used as a specificity control. XPB was pulled-down by GST-Tax but not by either GST or GST-CA (Fig. 1A), demonstrating a direct and specific interaction between Tax and XPB. Interestingly, XPB was also pulled-down by TaxM47, a mutant deficient in HTLV-1 transcriptional activation (33) (Fig. 1A). That XPB binds to Tax in vitro in the absence of the LTR and still interacts with TaxM47 suggests that the Tax/XPB interaction does not required assembly of the Tax-dependent transcription complex at the LTR.

FIG 1.

XPB binds to Tax. (A) GST-pulldown assay performed with GST, GST-CA, and GST-Tax (wt and M47 mutant) and in vitro transcribed/translated (TnT) XPB. Binding of XPB to the GST constructs was analyzed by immunoblot using an anti-XPB antibody. Protein inputs were determined by taking UV images of the SDS-PAGE gel before transfer. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of Tax and endogenous XPB in 293T cells. Cells were transfected with a control or Tax plasmid and total proteins prepared 24 h posttransfection were analyzed by immunoblot before (lysates) or after anti-Tax immunoprecipitation (IP Tax). (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of Tax and overexpressed XPB in 293T cells. Cells were cotransfected with a control or XPB plasmid together or not with the Tax plasmid and proteins were analyzed as in (B). (D) Coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous Tax and XPB produced in HTLV-1-transformed C8166 T cells. Immunoprecipitated proteins (IP Tax, upper) or total proteins obtained before (input) or after (flowthrough) IP (lower) were analyzed by immunoblot. Ig, signal corresponding to immunoglobulins used for the IP. Each panel corresponds to one representative experiment out of two or three performed.

Whether Tax and XPB also interact in cells was then investigated by coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Human 293T cells were transfected with a control or Tax expressor (endogenous XPB) or cotransfected with both Tax and XPB plasmids (overexpressed XPB). Immunoprecipitation of Tax allowed recovery of both endogenous (Fig. 1B) and overexpressed XPB (Fig. 1C). The same experiment was repeated in HTLV-1-infected C8166 T cells that endogenously produce Tax and XPB. Anti-Tax antibody precipitated XPB while only background signal was found with control IgG (Fig. 1D).

These data demonstrate that Tax and XPB directly interact, leading to the formation of intracellular Tax/XPB complexes in both overexpressed and endogenous conditions.

XPB is recruited at the proviral LTR.

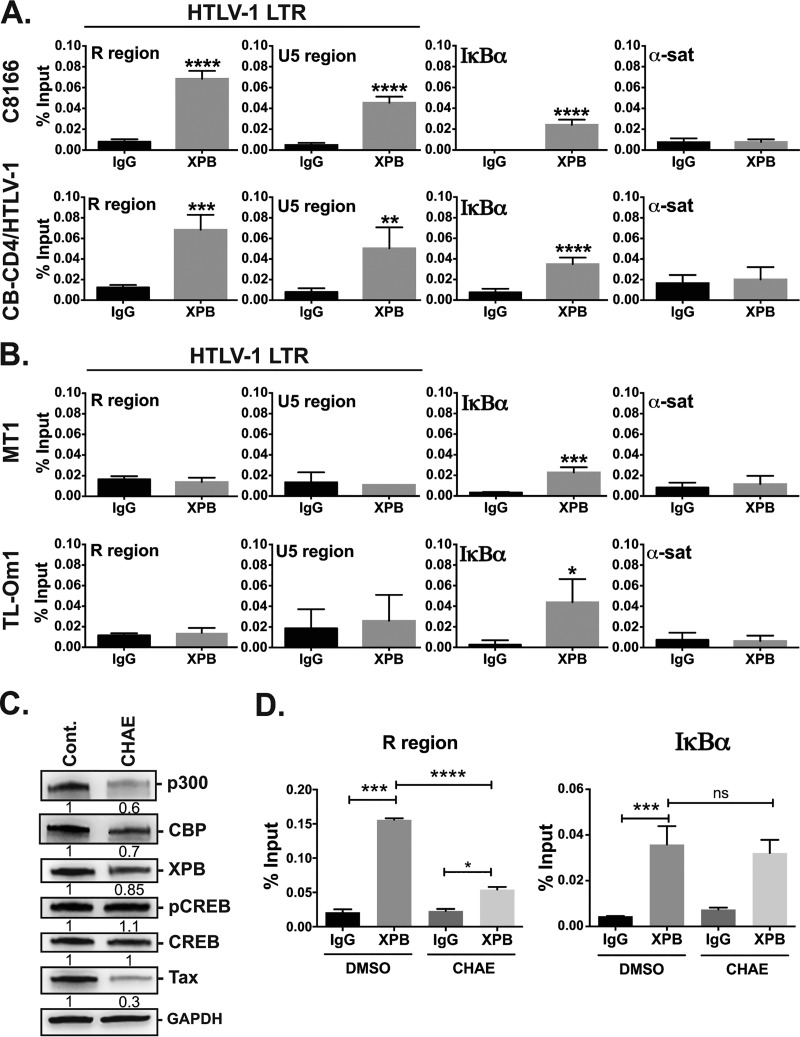

Whether XPB is recruited at the HTLV-1 LTR was examined by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments conducted in either Tax-positive (C8166) or Tax-negative/low (TL-Om1, MT-1) HTLV-1-transformed T cell lines. TL-Om1 T cells do not express Tax (34), while MT-1 T cells were recently shown to produce Tax only in a fraction of cells and in a transient manner (35). ChIP experiments were also performed on CB-CD4/HTLV-1-immortalized T cells generated upon in vitro activation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from a HAM/TSP patient (36). Importantly, CB-CD4/HTLV-1 T cells remain dependent on exogenous IL-2 and present the same Tax or HTLV-1 basic leucine zipper factor (HBZ) intracellular distributions as fresh PBMC from HAM/TSP patients (37).

Following chromatin immunoprecipitation with a control (IgG) or anti-XPB antibody, recovered DNA fragments were subjected to PCR using primers amplifying the R region of both the 5′ and 3′ LTRs or the U5 region of the 5′ LTR, each located downstream of the transcription start site. The IκBα (NFKBIA) promoter region, at which XPB was shown to be recruited (29), was amplified as a positive control. In addition, the nonrelated α-satellite region was amplified as a negative control.

In both C8166 and CB-CD4/HTLV-1 T cells, XPB recruitment was observed at the R and U5 LTR regions (Fig. 2A). In contrast, no LTR-specific signal (R or U5 region) was detected for either TL-Om1 or MT-1 T cells (Fig. 2B), strongly suggesting that XPB recruitment to the LTR depends on Tax. ChIP experiments were validated by the fact that for all T cell lines, positive XPB signals were found at the IκBα promoter but not at the α-satellite region (Fig. 2A and B). Of note, Tax-negative HTLV-1-transformed T cells were shown to maintain permanent NF-κB activation despite the absence of Tax (38), explaining the positive XPB signal found at the IκBα promoter for both TL-Om1 and MT-1 T cells.

FIG 2.

Endogenous XPB is recruited at the proviral LTR in a Tax-dependent manner. (A and B) ChIP experiments to detect XPB recruitment at various genomic loci. Sonicated chromatins prepared for Tax-positive C8166 and CB-CD4/HTLV-1 (A) or Tax-negative/low MT-1 and TL-Om1 HTLV-1-infected T cells (B) were amplified by PCR before (input) or after immunoprecipitation with control IgG or anti-XPB antibody. PCRs were performed using primers specific for the R or the 5′ LTR U5 region of the HTLV-1 LTR or for the IκBα promoter (positive control) and the α-satellite regions (negative control). PCR amplification of the chromatin (input) gave positive signals for both R and the 5′ LTR U5 regions in the four T cell lines (18 to 22 PCR cycles compared to 37 to 45 for water), confirming that they all carried integrated HTLV-1 genomes. Data correspond to means ± SEM of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. (C) Effect of chaetocin on XPB, Tax, and Tax cofactor expression levels. C8166 T cells were treated with 100 nM chaetocin for 24 h and the levels of endogenous p300, CBP, XPB, CREB, and Tax were analyzed by immunoblots (one representative experiment out of two). (D) Effect of chaetocin treatment on XPB recruitment to either the LTR or the IκBα promoter. ChIP analysis was performed as in (A). Data correspond to means ± SEM of one experiment performed in triplicate out of two. Statistical significance: ns, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

If XPB is recruited to the LTR in the course of HTLV-1 transcription, blocking LTR transactivation by Tax should lower the amount of XPB bound to the promoter. To address this hypothesis, we tried to deplete Tax via small interfering RNA (siRNA) in C8166 T cells, but obtained only a small decrease in global Tax levels (data not shown). Instead, we used chaetocin, an HSP90 inhibitor (39), since such inhibitors were previously shown to induce rapid Tax degradation (40). Treating C8166 T cells with chaetocin massively reduced Tax protein levels while having only a minor impact on XPB (Fig. 2C). Levels of total or phospho-CREB Ser133 were also not affected by chaetocin, while the amounts of CBP and p300 were reduced by 40% and 30%, respectively (Fig. 2C). Chaetocin treatment coincided with a statistically significant reduction of the level of XPB bound to the HTLV-1 LTR (Fig. 2D, left). In contrast, XPB was detected at the same level at the IκBα promoter (Fig. 2D, right), showing that chaetocin did not prevent XPB recruitment at chromatin in a general manner.

Collectively, these findings show that XPB recruitment at the proviral LTR depends on the transcriptional action of Tax and/or its cofactors.

XPB is involved in Tax-mediated but not basal LTR activation in T cells.

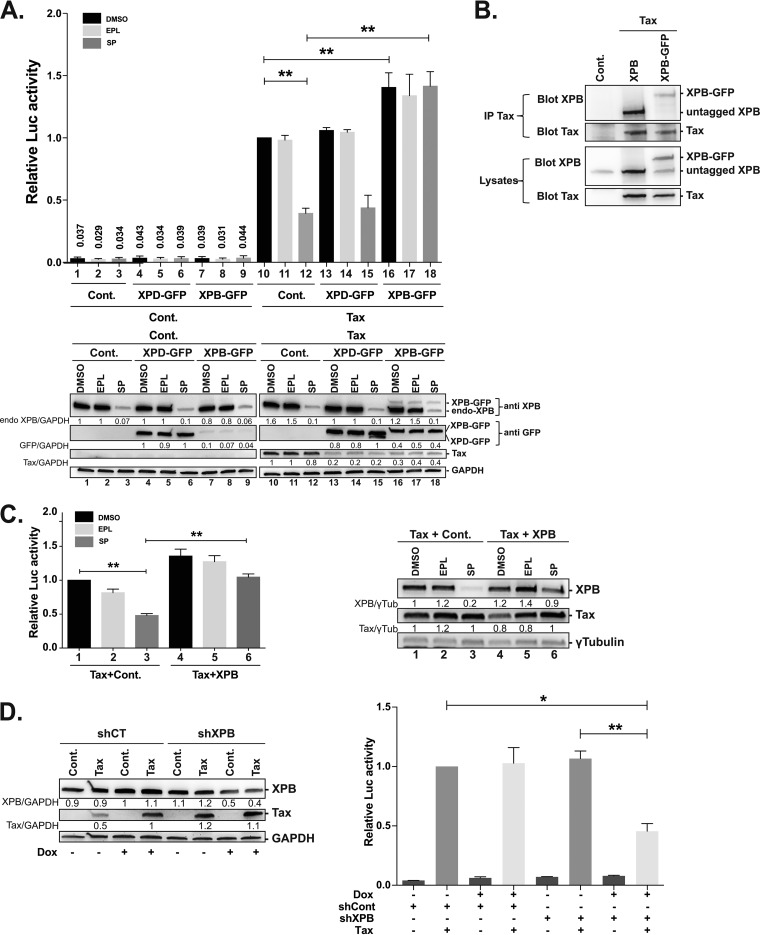

To directly assess the role of XPB in LTR activation, luciferase assays were performed in Jurkat T cells. We used an approach described by Elinoff al., based on XPB overexpression in cells treated with spironolactone (SP) in order to allow rapid XPB degradation (29). Moreover, to discriminate between endogenous and overexpressed XPB, an XPB-GFP construct was used and its impact compared to that of XPD-GFP. Importantly, fusion to green fluorescent protein (GFP) was previously shown to preserve incorporation into TFIIH and activities of both XPB and XPD (31, 41). In addition, we found that XPB-GFP retained the ability to coprecipitate with Tax (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

XPB is involved in Tax-mediated LTR activation. (A) Effect of XPB overexpression on HTLV-1 LTR activation in Jurkat T cells. Cells were transfected with the LTR U3R-Luc and pRL-TK reporter plasmids along with the control (basal) or Tax (transactivation) plasmids and with the XPB-GFP or XPD-GFP construct and then treated with DMSO or with EPL or SP at 10 μM for 24 h. Upper panel: relative luciferase activity calculated by normalizing firefly/renilla ratios to that of DMSO-treated Tax-transfected cells (set to 1). Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Lower panel: protein expression levels detected by immunoblots. Level of each band was normalized to the level of DMSO-treated control cells (lane 1). Data are from one representative experiment out of three. (B) XPB-GFP interaction with Tax. Human 293T cells were transfected with a control plasmid or with the Tax plasmid together with a plasmid encoding the untagged or GFP-fused version of XPB. Total (lysates) or anti-Tax immunoprecipitated (IP) proteins were blotted with the anti-XPB or anti-Tax antibody. (C) Effect of untagged XPB overexpression on HTLV-1 LTR activation in Jurkat T cells. Cells were transfected with the LTR U3R-Luc and pRL-TK reporter plasmids along with the Tax and XPB constructs and then treated with DMSO or with EPL or SP at 10 μM for 24 h. Left panel: relative luciferase activity calculated by normalizing firefly/renilla ratios to that of DMSO-treated Tax-transfected cells (set to 1). Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Right panel: protein expression levels detected by immunoblots. Level of each band was normalized to the level of DMSO-treated Tax-transfected cells (lane 1). Data are from one representative experiment out of two. (D) Effect of XPB knockdown on LTR activation by Tax. RFP positive-sorted Jurkat T cells producing the control of XPB shRNA were induced (dox+) or not (dox-) and transfected with the U3R-Luc and pRL indicator plasmids with or without the Tax plasmid. Left panel: expression of Tax and XPB analyzed by immunoblots. Data correspond to one representative experiment out of three. Right panel: luciferase production. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Statistical significance: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Jurkat T cells were transfected with the HTLV-1 U3R-Luc reporter construct and pRL-TK normalization plasmid together with a control (basal) or Tax (transactivation) plasmid and with the XPD-GFP or XPB-GFP expressor, and then treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), EPL, or SP for 24 h. Cotransfection with either XPD-GFP or XPB-GFP reduced the level of transfected Tax, presumably due to plasmid competition (Fig. 3A, lower, lanes 13 to 18). However, because the amount of Tax was not limiting in the experiment, this did not lower the level of LTR activation. Neither SP treatment nor XPB-GFP or XPD-GFP overexpression affected basal U3R-Luc activation (Fig. 3A, upper, bars 1 to 9). In contrast, Tax-mediated U3R-Luc activation was increased in the presence of XPB-GFP (Fig. 3A, upper, bars 10 and 16), while XPD-GFP had no effect (bars 10 and 13). Compared to DMSO-treated cells, Tax-mediated LTR activation was reduced by 60% in SP-treated cells (Fig. 3A, upper, bars 10 and 12). The level of transfected Tax was similar in the presence of either DMSO or SP (Fig. 3A, lower, lanes 10 and 12), indicating that SP neither blocked Tax production from a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter nor altered Tax stability. Strikingly, while overexpressed XPB-GFP was still sensitive to SP in the absence of Tax (Fig. 3A, lower, lanes 7 and 9), it was no more downregulated upon SP treatment in Tax-expressing cells (Fig. 3A, lower, lanes 16 and 18). Importantly, this resistance to SP coincided with complete rescue of the inhibitory effect of SP, independently of the Tax level (Fig. 3A, upper, bars 12 and 18). In contrast, no rescue was found for XPD-GFP (bars 12 and 15) despite that XPD-GFP was expressed at a higher level than XPB-GFP (Fig. 3A, lower, lanes 13 and 16). Anti-XPB immunoblotting showed small amounts of XPB-GFP compared to endogenous XPB (Fig. 3A, lower, lanes 16 to 18). This is expected since transfected cells (around 20% of the total population) are diluted by nontransfected cells, leading to underestimation of the level of XPB-GFP. We also noticed that XPB-GFP was barely detected in control cells (Fig. 3A, lower, lanes 7 to 9) while its level strongly increased upon Tax expression. Since higher expression, although less pronounced, was also observed for XPD-GFP cloned in the same vector, this effect may be due to an effect of Tax on the plasmid’s promoter. Importantly, overexpressing untagged XPB also compensated the negative effect of SP on Tax-mediated LTR activation (Fig. 3C), indicating that the rescue activity of XPB-GFP is indeed linked to XPB activity.

As a complementary approach to assess the role of XPB, XPB knockdown was performed in Jurkat T cells using a doxycycline-inducible control or an XPB short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vector. After induction (with dox) or not, cells were transfected with the reporter plasmids along or not with the Tax plasmid. XPB was downregulated by 60% in Jurkat-shXPB producing Tax, compared to Jurkat-shCont (Fig. 3D, left). Importantly, this coincided with a 55% reduction in Tax-mediated LTR activation despite that similar levels of transfected Tax were produced in the two conditions (Fig. 3D, right).

All together, these findings show that XPB is required for Tax-induced HTLV-1 LTR activation in both transfected and HTLV-1-infected T cells. In addition, the ability of overexpressed XPB to rescue SP inhibition confirms that SP acts on promoter transactivation in an XPB-dependent manner, which validates this drug as a relevant tool to analyze the impact of XPB downregulation on transcription.

The R-E-D domain of XPB is required for LTR transactivation and endogenous Tax production.

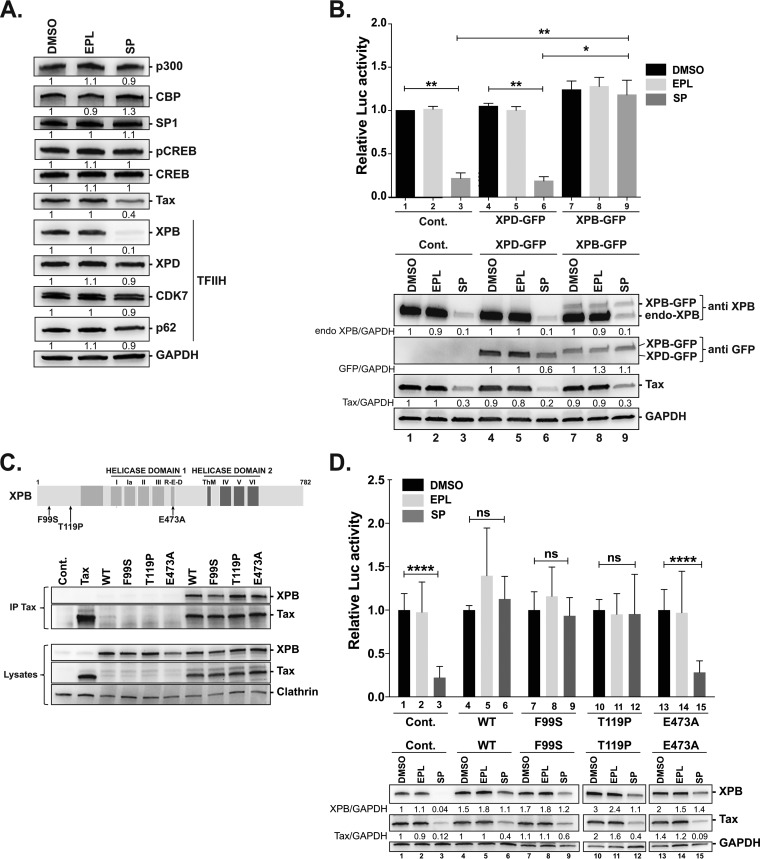

To address the role of XPB on transcription from integrated viral genomes, luciferase assays were performed in C8166 T cells that produce Tax endogenously. Presumably because of toxicity of the shXPB, we were unable to efficiently knock down XPB in C8166 T cells. Therefore, we used the SP approach validated in Jurkat T cells. Treating C8166 T cells with SP for 24 h massively reduced the level of XPB but not of the other TFIIH subunits XPD, cdk7, and p62 (Fig. 4A). This coincided with lower Tax production (Fig. 4A), suggesting that XPB downregulation affected viral expression from the proviral LTR. In contrast, SP did not alter expression of total or phospho-CREB, specific protein 1 (Sp1), or CPB/p300, known to modulate Tax-induced or basal LTR activation (42) (Fig. 4A). SP, but not EPL, reduced U3R-Luc transactivation by more than 70% (Fig. 4B, upper, bars 1 and 3). Consistent with data obtained in Tax-positive Jurkat T cells, overexpressed XPB-GFP was not downregulated upon SP treatment (Fig. 4B, lower, lanes 7 and 9) and rescued SP-mediated inhibition of LTR transactivation (Fig. 4B, upper, bars 3 and 9), while no rescue was observed with XPD-GFP (bars 3 and 6).

FIG 4.

The R-E-D domain of XPB is required for proviral LTR transactivation and endogenous Tax production. (A) Expression levels of LTR-regulating factors or TFIIH components in C8166 T cells treated with SP. (B) Capacity of XPB-GFP or XPD-GFP to rescue SP-mediated inhibition of LTR transactivation or endogenous Tax production. HTLV-1-transformed C8166 T cells were transfected with the LTR U3R-Luc and pRL-TK reporter plasmids and either the XPB-GFP or XPD-GFP construct and were then treated with DMSO or with EPL or SP at 10 μM for 48 h. Upper panel: relative luciferase activities calculated by normalizing firefly/renilla ratios to that of DMSO-treated control cells (bar 1). Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Lower panel: Tax, XPB-GFP, or XPD-GFP expression levels detected by immunoblotting. Data are from one representative experiment out of three. (C) Interaction of Tax with the XPB mutants. Upper panel: schematic representation of the XPB protein and position of the XPB mutations. Lower panel: interaction of Tax with wild-type XPB or XPB mutants. Human 293T cells were cotransfected with one of the XPB constructs along with a control or Tax expressor. Total proteins prepared 24 h posttransfection were analyzed before (lysates) or after the anti-Tax immunoprecipitation (IP Tax). Data correspond to one representative experiment out of two. (D) Capacity of wt or mutated XPB proteins to rescue SP-mediated inhibition of LTR transactivation or endogenous Tax production. HTLV-1-transformed C8166 T cells were transfected with the LTR U3R-Luc and pRL-TK reporter plasmids and one of the XPB constructs and were then treated with DMSO or with EPL or SP at 10 μM for 48 h. Upper panel: relative luciferase activity calculated by normalizing firefly/renilla ratios to that of DMSO-treated control cells (bar 1). Data are means ± SEM of five independent experiments performed in duplicate. Lower panel: Tax and XPB expression levels detected by immunoblotting. Data are from one representative experiment out of three. Statistical significance: ns, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001.

We then took advantage of rescue by overexpressed XPB to characterize which XPB activity is required for transactivation of the proviral LTR by Tax. XPB contains various functional domains (25). In particular, the R-E-D motif (Fig. 4C, upper) was shown to be required for optimal ATPase activity and promoter opening (26). We then used untagged XPB either as a wild-type (wt) form or carrying one of three mutations: F99S or T119P that do not perturb transcriptional activity but reduce (F99S) or maintain (T119P) DNA repair activity (27), or the R-E-D motif mutant XPB-E473A. Importantly, these three mutant proteins were previously shown to be properly incorporated within the TFIIH complex (26, 27). Moreover, coimmunoprecipitation experiments performed in cotransfected 293T cells demonstrated that each mutant form remains capable of interacting with Tax (Fig. 4C, lower).

Luciferase assays were then performed in HTLV-1-infected C8166 T cells transfected with the reporter plasmids and one of the XPB constructs in the presence of DMSO, EPL, or SP. A strong reduction in LTR transactivation was found in the SP-treated control cells (Fig. 4D, upper, bar 3). Overexpressing wt XPB, XPB-F99S, or XPB-T119P reversed the effect of SP on LTR activation by Tax (Fig. 4D, upper, bars 6, 9, and 12). In contrast, despite XPB-E473A being capable of increasing the level of total XPB similarly to wt XPB and the two other mutants (Fig. 4D, lower, lane 15), this mutant was unable to rescue LTR transactivation in SP-treated cells (Fig. 4D, upper, bar 15). Immunoblot analysis showed that overexpressing wt XPB, XPB-F99S, or XPB-T119P increased the level of endogenous Tax in SP-treated C8166 T cells (Fig. 4D, lower, lanes 6, 9, and 12). In contrast, no such increase was observed for XPB-E473A (Fig. 4D, lower, compare lane 15 to lane 1).

These results show that the R-E-D domain of XPB, needed for its optimal ATPase activity, is involved in Tax-induced LTR transactivation as well as endogenous Tax production in HTLV-1-infected T cells.

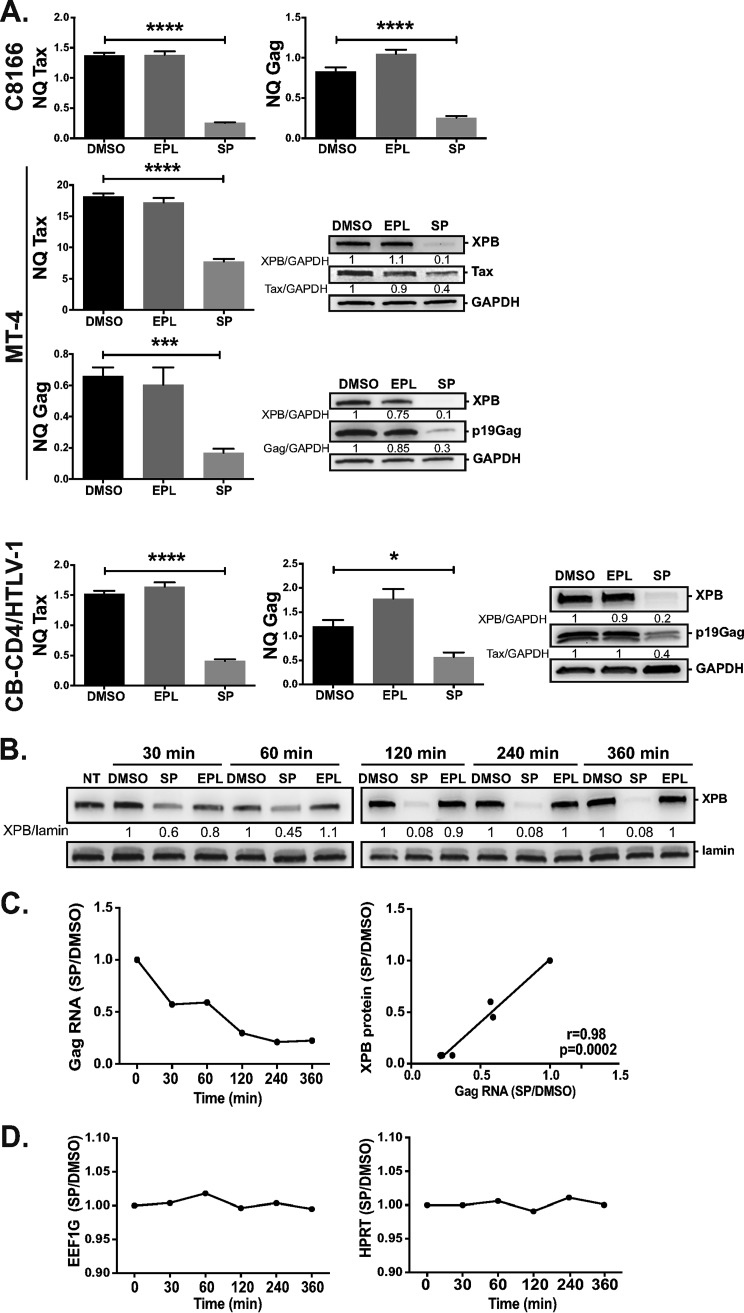

SP-mediated XPB downregulation inhibits viral transcription.

We next directly investigated the impact of XPB downregulation on HTLV-1 mRNA production by reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) experiments. C8166 and MT-4 HTLV-1-transformed T cells, as well as CB-CD4/HTLV-1-immortalized T cells, were treated with DMSO, SP, or EPL for 24 h. Of note, C8166 T cells exhibit a defect in viral RNA export and therefore do not produce Gag proteins but still generate Gag at the mRNA level (43). In C8166 T cells, SP treatment inhibited the production of Gag (Fig. 5A, upper). Tax mRNA production was also reduced in the presence of SP, confirming immunoblot data (see Fig. 4A). In MT-4 T cells, Tax and Gag production were also reduced at both the mRNA and protein levels in the presence of SP (Fig. 5A, middle). Of note is that lower production of Tax and Gag mRNA upon SP treatment was also found in CB-CD4/HTLV-1 T cells (Fig. 5A, lower). Consistent with a recent study (37), we found the level of Tax produced in CB-CD4/HTLV-1 T cells was quite low, preventing us from assessing the effect of SP on the Tax protein level in these cells.

FIG 5.

XPB downregulation inhibits viral transcription. (A) C8166 and MT-4 HTLV-1-transformed T cells or HTLV-1-immortalized CB-CD4/HTLV-1 T cells were treated with DMSO or with SP or EPL at 10 μM for 24 h. The level of Gag or Tax mRNA was quantified by RT-qPCR and normalized to the level of housekeeping genes (NQ). For MT-4 and CB-CD4/HTLV-1 T cells, the level of Gag protein (p19) was also analyzed by immunoblotting. Data correspond to one representative experiment out of two or three. (B) Time-course experiment to quantify the level of Gag mRNA over the course of SP treatment. C8166 T cells were either untreated (NT) or treated with DMSO or with SP or EPL at 10 μM. The level of XPB was analyzed at indicated times by immunoblotting in half of the cells. At each time point, the intensity of the XPB signal in EPL- or SP-treated cells was compared to that of DMSO-treated cells (set to 1). Data correspond to one representative experiment out of three. (C) The other half of the cells was used to quantify the level of Gag mRNA. Left panel shows the SP/DMSO ratios calculated from the level of RNA normalized to the level of housekeeping genes (NQ). Right panel shows the correlation between the level of XPB protein quantified from (B) and the SP/DMSO ratios shown in the left panel. (D) Effect of SP on the levels of housekeeping gene mRNAs. Data show the SP/DMSO ratios for EEF1G or HPRT calculated from relative quantities using the formula: Q = 2−ΔCp. Data correspond to one representative experiment performed in triplicate out of three. Statistical significance: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

To further study the link between XPB and HTLV-1 RNA production, the level of HTLV-1 Gag mRNA was quantified in the course of SP treatment. C8166 T cells were treated with DMSO, EPL, or SP up to 6 h. In agreement with previous data (30), a decrease in XPB levels can already be seen 30 min posttreatment, with a maximal reduction at 120 min (Fig. 5B). Reduction of Gag mRNA was already apparent at 30 min (Fig. 5C, left), coinciding with the beginning of XPB downregulation (Fig. 5B). Moreover, a solid positive correlation was found between the level of Gag mRNA and the amount of XPB protein over the course of SP treatment (Fig. 5C, right). Importantly, no significant variation in the level of HPRT or EEF1G housekeeping gene mRNAs was observed (Fig. 5D), confirming that SP does not act as a general inhibitor of Pol II-mediated transcription.

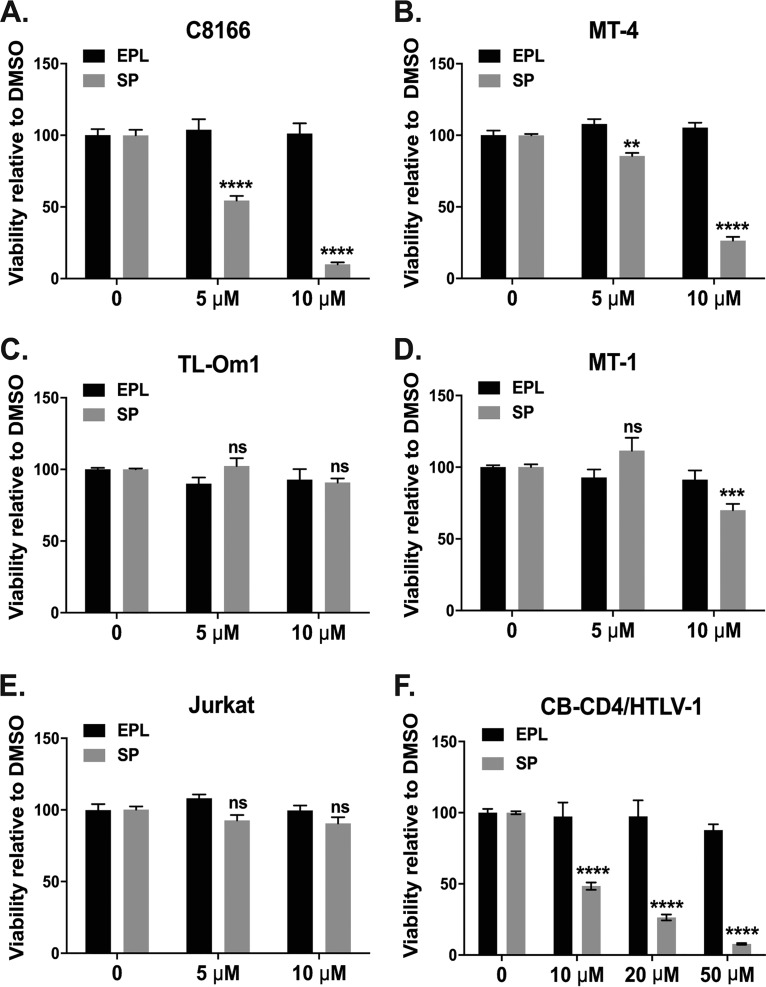

SP-mediated XPB downregulation inhibits growth of Tax-positive HTLV-1-infected T cells.

We at last studied the effect of XPB downregulation on the growth of HTLV-1-infected T cells. Cells were treated every day with DMSO or with EPL or SP and the number of living cells were quantified by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method after 72 h of culture. Compared to DMSO and EPL, SP reduced the viability of C8166 (Fig. 6A) and MT-4 (Fig. 6B) T cells in a dose-dependent manner. The same treatments were applied on Tax-negative/low HTLV-1-infected T cells (MT-1, TL-Om1) and uninfected T cells (Jurkat). Neither SP nor EPL impacted viability of TL-Om1 (Fig. 6C) or Jurkat (Fig. 6E) T cells. Interestingly, SP at 10 μM slightly decreased viability of MT-1 T cells (Fig. 6D), in agreement with the transient expression of Tax by this cell line (35). Importantly, SP treatment also reduced viability of CB-CD4/HTLV-1 T cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6F), demonstrating that its cytotoxic effect also occurred for HTLV-1-immortalized primary T cells.

FIG 6.

XPB downregulation reduces viability of Tax-positive HTLV-1-infected T cells. C8166 (A), MT-4 (B), TL-om1 (C), MT-1 (D), Jurkat transformed T cells (E), and HTLV-1 immortalized CB-CD4/HTLV-1 cells (F) were treated every day with DMSO (0) or with EPL or SP at the indicated concentrations and cell viability was determined by the MTT method after 3 days of culture. The viability values for SP or EPL were normalized to that of DMSO-treated cells (set as 100%). For each cell line, viability results correspond to two independent experiments performed in triplicate. Ns, not significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, ****, P < 0.0001.

These data show that the effect of XPB downregulation on HTLV-1 RNA production translates into inhibition of proliferation of Tax-positive HTLV-1-infected T cells, reinforcing the link between XPB and Tax expression.

DISCUSSION

As emphasized in recent reviews, HTLV-1 is considered the most potent cancer-associated virus and still remains a significant threat to human health (44, 45). Deciphering the mechanisms by which the HTLV-1 transactivator Tax regulates HTLV-1 gene expression is therefore a central issue for both fundamental and therapeutic aspects. In this study, we describe a novel physical and functional interaction between Tax and the XPB subunit of the general transcription factor TFIIH.

First, we showed that GST-Tax is able to pull down in vitro-synthesized XPB, proving a direct interaction. That Tax produced in bacteria interacts with XPB also strongly suggests that the posttranslational modifications of Tax are not required for XPB binding. Similar data were obtained for TBP, TFIIA, and the cdk9 subunit of pTEFb (13, 16, 46), suggesting that the same unmodified Tax form may associate with the preinitiation and elongation complexes. In addition, we documented that Tax coprecipitates with endogenous XPB in 293T cells as well as in HTLV-1-infected T cells. Next, we showed that endogenous XPB is bound to the HTLV-1 LTR in Tax-positive but not Tax-negative HTLV-1-tranformed T cells, suggesting that XPB recruitment to the LTR depends on Tax. Importantly, XPB recruitment at the LTR was also observed in HTLV-1-immortalized T cells generated from PBMC from a HAM/TSP patient. The requirement of Tax-mediated LTR transcription for XPB recruitment at the LTR was further documented by data showing that inducing degradation of Tax and/or its transcriptional cofactors upon chaetocin treatment significantly reduced the amount of XPB bound to the LTR. Of note, we checked that chaetocin treatment used to induce Tax degradation has only little impact on XPB production. Furthermore, chaetocin did not prevent XPB recruitment at a cellular promoter, showing that XPB functionality was preserved. All together, these data provide direct evidence that XPB is a novel direct partner of Tax recruited at the LTR of integrated viral genomes during active transcription in both HTLV-1-transformed T cells and in vivo-infected T cells.

To explore the impact of XPB on HTLV-1 transcription, we took advantage of the ability of spironolactone (SP) to induce XPB degradation. Indeed, as previously shown by Alekseev et al. (30) and confirmed in this study, SP is a very effective tool to manipulate XPB as it induces almost complete XPB downregulation in less than 2 h. Moreover, the effect of SP can be compared to that of the SP derivative eplerenone (EPL), which blocks aldosterone binding to the mineralocorticoid receptor in the same way as does SP but does not induce XPB degradation (30, 32). We found that inducing XPB degradation using SP significantly reduced Tax-mediated LTR transactivation in Jurkat T cells with no impact on Tax stability. SP-mediated XPB downregulation also inhibits LTR transactivation by endogenous Tax in HTLV-1-transformed T cells, while the levels of Tax cofactors or other TFIIH subunits were not affected. Importantly, no significant change in Tax-mediated LTR transactivation was observed upon treatment with EPL, arguing against a role of aldosterone signaling modulation in LTR inhibition. To further substantiate the role of XPB, we examined the impact of shRNA-mediated depletion of XPB on Tax-induced LTR activation. Of note, as pointed out in reference 21, si/shRNAs are not considered an adequate tool to study the role of XPB in transcription. The reason is that XPB is a core subunit of TFIIH (47), such that blocking XPB production by si/shRNA alters TFIIH assembly. This is not observed with SP since this drug targets XPB proteins already incorporated within TFIIH (31), allowing the study of XPB-minus TFIIH complexes. We nevertheless studied the effect of an shRNA directed to XPB using an inducible vector and found that, compared to the control shRNA, XPB shRNA significantly reduces Tax-mediated U3R-Luc activation in T cells, confirming the role of TFIIH/XPB in transactivation of the HTLV-1 LTR.

Further strong evidence for a key role of XPB in HTLV-1 LTR activation came from rescue experiments. Indeed, overexpressing an XPB-GFP protein is sufficient to reverse the negative effect of SP on Tax-induced LTR transactivation in either transfected Jurkat T cells or HTLV-1-infected C8166 T cells. Importantly, rescue was not observed with overexpressed XPD-GFP, underlying the specific role of XPB. Complete rescue was also found when untagged XPB was overexpressed, ruling out a role of the GFP fusion in the rescue property of XPB-GFP. Interestingly, we found that XPB-GFP and untagged XPB were, respectively, no more (Fig. 3A) or less (Fig. 3C) degraded upon SP treatment in the presence of Tax. Of note, both untagged XPB and XPB-GFP were still downregulated upon SP treatment in the absence of Tax, even though XPB-GFP appears less sensitive that the untagged form, as previously observed (30). In contrast, we observed that XPB is properly degraded by SP in HTLV-1-infected T cells that express Tax (Fig. 4 and 5). Therefore, Tax appears to protect overexpressed but not endogenous XPB from SP-induced degradation. Since transfection results in a high level of expression per cell and since Tax increased XPB-GFP production from the plasmid, this resistance to degradation could be due to an improper ratio between overexpressed XPB and the cellular proteins mediating SP-induced XPB degradation. Whatever the mechanism involved, SP resistance in the presence of Tax provides the molecular explanation for the ability of overexpressed XPB and XPB-GFP to rescue inhibition of Tax-induced LTR activation by SP.

The rescue property of overexpressed XPB also gave us the opportunity to identify the domain of XPB involved in Tax-mediated HTLV-1 transcription. We found that wild-type XPB and two XPB mutants defective for DNA repair but retaining transcriptional activity, fully compensated SP-mediated XPB downregulation in C8166 T cells. In contrast, no compensation was achieved with a mutant bearing a mutation in the R-E-D domain regulating XPB ATPase activity (26). This strongly suggests that the ATPase-dependent activity of XPB, necessary for the promoter opening activity, is indeed the one cooperating with Tax during HTLV-1 transcription.

Importantly, we also provide evidence that inducing XPB degradation had major consequences on viral RNA expression and the viability of HTLV-1-infected T cells. Indeed, we showed that SP reduces the production of HTLV-1 Gag and Tax mRNA and there is a solid correlation between the level of Gag mRNA and the level of XPB. Moreover, we found that compared to EPL, SP inhibits the proliferation of both HTLV-1-transformed and HTLV-1-immortalized T cells, proving that the effect of XPB downregulation is not restricted to HTLV-1-transformed T cell lines. In contrast, SP had no effect on either uninfected T cells or Tax-negative HTLV-1-infected T cells. This reinforces the functional link between XPB and Tax and confirms the key role of Tax in the survival of Tax-positive HTLV-1-infected T cells (48). These findings also reveal that via its ability to downregulate XPB, SP is a potent inhibitor of Tax-induced HTLV-1 gene expression as well as Tax-driven T cell proliferation.

Since XPB belongs to a complex of general transcription factors, one could assume that its downregulation would block transcription in a general manner. However, the role of XPB is more complex. Indeed, while XPB appears to be dispensable for basal transcription, it is required for transcription induced by certain stimuli. In good agreement with this, TFIIH was shown to be at least partially dispensable in the case of promoters with preformed transcription bubbles (49), while the promoter-opening step, controlled by XPB, is considered an important regulatory step for inducible promoters (50). We found here that SP-mediated degradation of XPB impacts Tax-mediated but not basal HTLV-1-LTR activity in Jurkat T cells. Noteworthy, we previously reported that SP inhibits Tat-dependent but not basal transcription of the HIV-1 LTR (32). Our data therefore provide new evidence for a role of XPB in inducible viral transcription by showing that XPB is also involved in HTLV-1 RNA production.

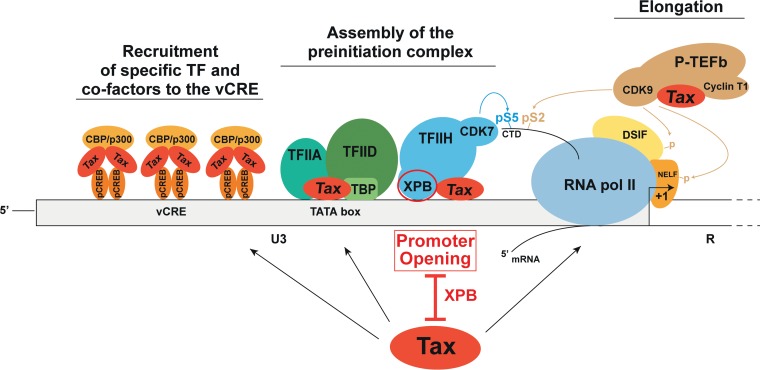

Our demonstration that Tax interacts with XPB raises the issue of whether XPB could also directly interact with Tat to accomplish its function on the HIV-1 LTR promoter. In this line, it would also be of interest to study the recruitment of XPB to the HIV-1 LTR sequence. Both HIV-1 Tat (51) and HTLV-1 Tax (16) interact with pTEF-b but, in contrast to Tat, Tax is able as well to recruit TFIIA and TFIID to the promoter. These findings, along with our present data, support a model in which Tax not only recruits specific transcription factors to the promoter but also controls subsequent steps of the transcription process by successively recruiting at least one subunit of each GTF complex acting together with RNA Pol II (Fig. 7). This provides another example of the powerful ability of Tax to manipulate cellular machineries.

FIG 7.

Model illustrating the capacity of Tax to target essential steps of the Pol II-mediated transcription process, including the promoter-opening step controlled by the XPB subunit of TFIIH.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that XPB is a member of the Tax-dependent transcription complexes assembled at the HTLV-1 LTR in the course of viral transcription. Our data also suggest that the promoter-opening step of transcription plays a key role in HTLV-1 gene expression. These findings provide new insights on the molecular players governing HTLV-1 transcription and may open new avenues of research for the development of therapeutic interventions targeting HTLV-1 transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and transfection.

HEK-293T (American Type Culture Collection number CRL-3216) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Dutcher), 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM pyruvate, and antibiotics (Invitrogen) and were transfected using the phosphate calcium procedure. CD4+ Jurkat T-cells (kindly provided by S. Emiliani, Institut Cochin, France) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented as above. The HTLV-1-infected CD4+ T cell lines C8166 and MT-4 (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, USA), TL-Om1, and MT-1 (kindly provided by Edward Harhaj, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, USA) were grown in supplemented RPMI 1640 containing also 25 mM glucose, 20 mM HEPES, and 5 ml of 100× nonessential amino acid solution (Invitrogen). T cell lines were transfected using the DMRIE-C reagent (Roche). HTLV-1-immortalized CB-CD4/HTLV-1 T cells generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of a TSP/HAM patient have been described (36). These cells were grown in supplemented RPMI medium in the presence of 50 U/ml of IL-2 (Roche).

Plasmids.

The pSG5M empty vector and the pSG5M-Tax plasmids have been described (52). The pGEX-2T and pGEX-2T-Tax (wt and m47) plasmids were kindly provided by V. Mocquet (ENS, Lyon, France) and the pGEX-2T-p24 (GST-CA) was previously described (53). The U3R-Luc (Firefly) plasmid was kindly provided by A. Kress (Institute of Clinical and Molecular Virology, Erlangen, Germany). The normalization plasmid pRL-TK (Renilla) was obtained from Promega. The pTRIPZ-shRNA control and pTRIP-shRNA ERCC3/XPB (RHS4696-200709382) constructs harboring a doxycycline-inducible promoter driving both RFP and shRNA expression were obtained from Horizon. The peGFP-N2-XPD (XPD-GFP) and peGFP-N1-XPB (XPB-GFP) constructs (54, 55) were kindly provided by W. Vermeulen (ERASMUS MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands). To generate the pcDNA3-XPB plasmid, human XPB cDNA was cloned from total RNA extracted from Jurkat T cells by using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). One μg of total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription using the Maxima reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PCR amplification was performed on a fraction of RT products with the high fidelity Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) using the oligonucleotides XPB-BamHI Fw (5′-GCGCCTCGAGGATCCACCATGGGCAAAGAGACCGAGGC-3′) and XPB NheI Rev (5′-GCGCACGCGTGCGGCCGCTAGCTCATTTCCTAAAGCGCTTGAAG-3′). Products were then cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The XPB insert was then digested with BamHI and NheI and cloned into the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen). XPB mutagenesis was performed on the pcDNA3-XPB plasmid by PCR amplification with the high fidelity proofreading Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) using primers as follows: F99S (forward 5′-CAAATATGCCCAAGACTCCTTGGTGGCTATTGC-3′ and reverse 5′-GCAATA GCCA CCAAGGAGTCTTGGGCATATTTG-3′); T119P (forward 5′-CATGAGTACAAACTA CCTGCCTACTCCTTG-3′ and reverse 5′-CAAGGAGTAGGCAGGTAGTTTGTACTCATG-3′); E473A (forward 5′-GCGACCCTCGTCCGCGCAATGACAAAATTGTG-3′ and reverse 5′-CACAATTTTGT CATCTGCGCGGA CGAGGGTCGC-3′). Sequencing of the wt and mutated plasmids showed that the XPB ORF was identical in each cDNA except for the presence of the introduced mutation.

Antibodies and reagents.

The anti-XPB monoclonal antibody from Novusbio (NB10061060) was used for ChIP experiments. The other primary antibodies used in immunoblots were as follows: anti-p300 (Bethyl Laboratories, A300-358A); anti-CBP (Invitrogen, PA5-27369); anti-XPD (Cell Signaling, 11963); anti-p62 (Invitrogen, PA5-83832); anti-CDK7 (Bethyl Laboratories, A700-006-T); anti-XPB (Santa Cruz, s19); anti-CREB (Sigma-Aldrich, 17-600); anti-phospho-CREB-Ser133 (Millipore, CS 204400); anti-Sp1 (Abcam ab13370); anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz, sc32233); anti-γ-tubulin (Abcam ab16504); anti-lamin A/C (Cell signaling, 2032S); anti-clathrin (SCBT, sc-12734); and anti-IgG rabbit (Millipore PP64B). Horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-human, anti-mouse, and anti-rabbit IgG (Promega) were used as secondary antibodies. Spironolactone (SP), eplerenone (EPL), and chaetocin (all from Sigma) were diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as 10 mM stock solutions.

XPB knockdown.

Stable shRNA transfectants were generated by transfecting Jurkat T cells (2 × 106 cells in 6-well plates) with 4 μg of inducible pTRIPZ-RFP-shRNA constructs. After 48 h, 0.5 μg/ml of puromycin was added to the medium to select transfected cells. Puromycin-resistant cells were then treated with doxycycline (2 μg/ml) for 3 days and RFP-positive cells were sorted using a MoFlo Astrios sorter.

Luciferase assays.

T cells (3 × 105/24 well in duplicate) were cotransfected using the DMRIE-C reagent (Roche) with 100 ng of the U3R-Luc plasmid, 10 ng of pRL-TK, and 250 ng of the control, Tax, or XPB plasmid/well. After 48 h, cells were lysed in 100 μl of passive lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase activities were quantified using the dual luciferase assay system (Promega) and firefly activity values were normalized to that of renilla activity.

GST pulldown.

GST proteins were produced using BL21-DE3 Escherichia coli cells (Promega) transformed with the pGEX plasmids and induced with isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.1 mM) at 20°C overnight. Bacteria pellets corresponding to 500 ml of culture were incubated with 10 ml of lysis buffer (Tris HCl 50 mM pH 7.5; KCl 150 mM; Triton 10%) and then sonicated (30 sec ON/30 sec OFF; amplitude 70%) during 5 min. Lysates were then incubated for 2 h at 4°C with 200 μl of dry glutathione sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) in 20 ml reaction volume and beads were washed 3 times with cold binding buffer (Tris HCl 50 mM pH 7.4; EDTA 1 mM; NaCl 250 mN; NP-40 0,1%). XPB was synthesized in vitro from the pcDNA3-XPB plasmid using the T7-TnT coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega). TnT reaction mixtures (15 μl) were incubated with 10 μg of GST-fusion protein for 1 h at room temperature. Beads were then washed 5 times with cold binding buffer before elution with 50 μl of elution buffer (0.3 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.04% bromophenol blue, and dithiothreitol [DTT] 100 mM) and proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE were analyzed by immunoblotting. UV images of the gels were taken before transfer to determine the inputs.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Human 293T cells (1.5 × 106 cells in a 10-cm dish) were transfected with 6 μg of the control, Tax, or XPB plasmid and lysed 48 h posttransfection. Transfected 293T cells or C8166 T cells (5 × 106) were lysed in 500 μl of radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 150 mM NaCl) supplemented with protease inhibitor and benzonase nuclease (Sigma). The lysates (500 μg) were incubated overnight with 3 μg of primary antibodies at 4°C and 10 μg of the lysates were used for Western blot analysis. Immunocomplexes were then captured on protein A/G-agarose beads (Thermoscientific 20421) 1 h at 4°C. Beads were then washed 5 times in wash buffer (120 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.2 mM NaF, 0.2 mM EGTA, 0.2% deoxycholate, 0.5% NP-40) before elution in 50 μl of Laemmli buffer (0.3 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.04% bromophenol blue, DTT 100 mM). Immunoprecipitated proteins or total cell lysates were separated on 4 to 15% SDS-PAGE precast gels (Bio-Rad), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 μm), and blotted with specific antibodies. Images were acquired using a Fusion Fx camera (Vilber Lourmat). Band quantification was performed with the Image J software after subtraction of the background.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR.

Total RNAs were prepared with the Nucleospin RNAII kit (Macherey-Nagel, France) and 1 μg was reverse transcribed using the Maxima first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, France). Real-time PCR were performed on 1/10 of the reverse transcription reaction. HTLV-1 genomic RNA (gRNA) and housekeeping control RNAs were amplified using the Sybr green reagent (Roche) with the following primers: unspliced Gag mRNA (region 2,036 to 2,224, forward 5′-CAGAGGAAGATGCCCTCCTATT-3′ and reverse 5′-GTCAACCTGGGCTTTAATTACG-3′); EEF1G (forward 5′-AGATGGCCCAGTTTGATGCTAA-3′ and reverse 5′-GCTTCTCTTCCCGTGAACCCT-3′); HPRT (forward 5′-TGACACTGGCAAAACAATGCA-3′ and reverse 5′-GGTCCTTTTCACCAGCAAGCT). Tax mRNA was quantified using the TaqMan method using the primers forward 5′-ATCCCGTGGAGACTCCTCAA-3′ and reverse 5′-GGATACCCAGTCTACGTGTTTGG-3′ and a probe encompassing the spliced junction 5′-TCCAACACCATGGCCCACTTCCC-3′. PCR conditions were as followed: preincubation 95° 5 min; amplification (45 cycles); denaturation 95° 10 sec; annealing 60° 20 sec; extension 72° 10 sec; acquisition, melting curve, cooling. The normalized quantity (NQ) of each mRNA was determined by normalizing their level to that of the housekeeping genes EEF1G and HPRT according to the following formula: NQ = 2−(cp−((cpEEF1G+cpHPRT)/2)).

ChIP experiments.

Before the experiment, 107 cells were cross-linked using 1.1% formaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 8 min at room temperature. Chromatin was then sheared using a Bioruptor Pico sonicator (Diagenode) to obtain fragments of around 300 bp. Immunoprecipitations were performed using the ChIP-IT high sensitivity kit (Active motif) on 10 μg of chromatin using 4 μg of specific or control antibodies and 10% of chromatin was kept for inputs. qPCR was conducted with the following primers: α-sat (forward 5′-CTGCACTACCTGAAGAGGAC-3′ and reverse 5′-GATGGTTCAACACTCTTACA-3′); IκBα (SimpleChIP human IκBα promoter primers number 5552, Cell Signaling Technology); LTR R region (forward 5′-CGCATCTCTCCTTCACGCGC-3′ and reverse 5′-CGGTCTCGACCTGAG-3′); or LTR U5-Gag region (forward 5′-GACAGCCCATCCTATAGCACTC-3′ and reverse 5′-CTAGCGCTACGGGAAAAGATT-3′).

Cell viability assays.

Cell viability was quantified by measuring the rate of mitochondrial reduction of yellow tetrazolium salt MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (Sigma) to insoluble purple crystals. Cells were cultured for 72 h with DMSO, EPL, or SP and MTT solution (25 μl of a solution at 5 mg/ml) was added to each well for 2 h. The supernatant was then removed and 50 μl of DMSO added to dissolve formazan crystal. Optical densities (OD) were measured at 590 nm with a Tecan infinite Pro 2000 spectrophotometer.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were conducted with the GraphPad Prism 6 software. Two-group comparison was done using the paired t test and multiple-group analysis with the one-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. Correlation analysis was done using the Pearson test. Statistical significance was defined for P values < 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, for HTLV-1-infected T cell lines and A. Kress, W. Vermeulen, and V. Mocquet for the plasmids. We also thank the staff of the genomic (GENOM’IC) and cytometry (CYBIO) facilities of the Cochin Institute for their expertise.

This work was supported by grants from the Ligue contre le Cancer (Comité Ile de France; https://www.ligue-cancer.net/cd75) and from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM; grant number DEQ20140329528 awarded to F.M.-G.; https://www.frm.org/). C.M. and A.I.T. were recipients of Ph.D. grants from the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (https://www.ligue-cancer.net) or from the Université Paris Descartes (https://www.parisdescartes.fr/) and the Fondation ARC (https://www.fondationarc.org/), respectively. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hermine O, Ramos JC, Tobinai K. 2018. A review of new findings in adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma: a focus on current and emerging treatment strategies. Adv Ther 35:135–152. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0658-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panfil AR, Martinez MP, Ratner L, Green PL. 2016. Human T-cell leukemia virus-associated malignancy. Curr Opin Virol 20:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bangham CR, Araujo A, Yamano Y, Taylor GP. 2015. HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 1:15012. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currer R, Van Duyne R, Jaworski E, Guendel I, Sampey G, Das R, Narayanan A, Kashanchi F. 2012. HTLV tax: a fascinating multifunctional co-regulator of viral and cellular pathways. Front Microbiol 3:406. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kfoury Y, Nasr R, Journo C, Mahieux R, Pique C, Bazarbachi A. 2012. The multifaceted oncoprotein Tax: subcellular localization, posttranslational modifications, and NF-kappaB activation. Adv Cancer Res 113:85–120. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394280-7.00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasegawa H, Sawa H, Lewis MJ, Orba Y, Sheehy N, Yamamoto Y, Ichinohe T, Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y, Katano H, Takahashi H, Matsuda J, Sata T, Kurata T, Nagashima K, Hall WW. 2006. Thymus-derived leukemia-lymphoma in mice transgenic for the Tax gene of human T-lymphotropic virus type I. Nat Med 12:466–472. doi: 10.1038/nm1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellon M, Baydoun HH, Yao Y, Nicot C. 2010. HTLV-I Tax-dependent and -independent events associated with immortalization of human primary T lymphocytes. Blood 115:2441–2448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-241117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nyborg JK, Egan D, Sharma N. 2010. The HTLV-1 Tax protein: revealing mechanisms of transcriptional activation through histone acetylation and nucleosome disassembly. Biochim Biophys Acta 1799:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen FX, Smith ER, Shilatifard A. 2018. Born to run: control of transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19:464–478. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nogales E, Louder RK, He Y. 2017. Structural insights into the eukaryotic transcription initiation machinery. Annu Rev Biophys 46:59–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070816-033751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemasson I, Polakowski NJ, Laybourn PJ, Nyborg JK. 2002. Transcription factor binding and histone modifications on the integrated proviral promoter in human T-cell leukemia virus-I-infected T-cells. J Biol Chem 277:49459–49465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209566200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Fuente C, Kashanchi F. 2004. The expanding role of Tax in transcription. Retrovirology 1:19. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clemens KE, Piras G, Radonovich MF, Choi KS, Duvall JF, DeJong J, Roeder R, Brady JN. 1996. Interaction of the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 tax transactivator with transcription factor IIA. Mol Cell Biol 16:4656–4664. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caron C, Mengus G, Dubrowskaya V, Roisin A, Davidson I, Jalinot P. 1997. Human TAF(II)28 interacts with the human T cell leukemia virus type I Tax transactivator and promotes its transcriptional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:3662–3667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson MG, Scoggin KE, Simbulan-Rosenthal CM, Steadman JA. 2000. Identification of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase as a transcriptional coactivator of the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax protein. J Virol 74:2169–2177. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2169-2177.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou M, Lu H, Park H, Wilson-Chiru J, Linton R, Brady JN. 2006. Tax interacts with P-TEFb in a novel manner to stimulate human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 transcription. J Virol 80:4781–4791. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4781-4791.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho WK, Zhou M, Jang MK, Huang K, Jeong SJ, Ozato K, Brady JN. 2007. Modulation of the Brd4/P-TEFb interaction by the human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 tax protein. J Virol 81:11179–11186. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00408-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rimel JK, Taatjes DJ. 2018. The essential and multifunctional TFIIH complex. Protein Sci 27:1018–1037. doi: 10.1002/pro.3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Compe E, Egly JM. 2016. Nucleotide excision repair and transcriptional regulation: TFIIH and beyond. Annu Rev Biochem 85:265–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fishburn J, Tomko E, Galburt E, Hahn S. 2015. Double-stranded DNA translocase activity of transcription factor TFIIH and the mechanism of RNA polymerase II open complex formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:3961–3966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417709112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alekseev S, Nagy Z, Sandoz J, Weiss A, Egly JM, Le May N, Coin F. 2017. Transcription without XPB establishes a unified helicase-independent mechanism of promoter opening in eukaryotic gene expression. Mol Cell 65:504–514.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim TK, Ebright RH, Reinberg D. 2000. Mechanism of ATP-dependent promoter melting by transcription factor IIH. Science 288:1418–1422. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tirode F, Busso D, Coin F, Egly JM. 1999. Reconstitution of the transcription factor TFIIH: assignment of functions for the three enzymatic subunits, XPB, XPD, and cdk7. Mol Cell 3:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin YC, Choi WS, Gralla JD. 2005. TFIIH XPB mutants suggest a unified bacterial-like mechanism for promoter opening but not escape. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nsmb949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oksenych V, Coin F. 2010. The long unwinding road: XPB and XPD helicases in damaged DNA opening. Cell Cycle 9:90–96. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.1.10267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oksenych V, Bernardes de Jesus B, Zhovmer A, Egly JM, Coin F. 2009. Molecular insights into the recruitment of TFIIH to sites of DNA damage. EMBO J 28:2971–2980. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coin F, Oksenych V, Egly JM. 2007. Distinct roles for the XPB/p52 and XPD/p44 subcomplexes of TFIIH in damaged DNA opening during nucleotide excision repair. Mol Cell 26:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandoz J, Coin F. 2017. Unified promoter opening steps in eukaryotic gene expression. Oncotarget 8:84614–84615. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elinoff JM, Chen LY, Dougherty EJ, Awad KS, Wang S, Biancotto A, Siddiqui AH, Weir NA, Cai R, Sun J, Preston IR, Solomon MA, Danner RL. 2018. Spironolactone-induced degradation of the TFIIH core complex XPB subunit suppresses NF-kappaB and AP-1 signalling. Cardiovasc Res 114:65–76. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alekseev S, Ayadi M, Brino L, Egly JM, Larsen AK, Coin F. 2014. A small molecule screen identifies an inhibitor of DNA repair inducing the degradation of TFIIH and the chemosensitization of tumor cells to platinum. Chem Biol 21:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ueda M, Matsuura K, Kawai H, Wakasugi M, Matsunaga T. 2019. Spironolactone-induced XPB degradation depends on CDK7 kinase and SCF(FBXL) (18) E3 ligase. Genes Cells 24:284–296. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lacombe B, Morel M, Margottin-Goguet F, Ramirez BC. 2016. Specific inhibition of HIV infection by the action of spironolactone in T cells. J Virol 90:10972–10980. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01722-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith MR, Greene WC. 1990. Identification of HTLV-I tax trans-activator mutants exhibiting novel transcriptional phenotypes. Genes Dev 4:1875–1885. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.11.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hironaka N, Mochida K, Mori N, Maeda M, Yamamoto N, Yamaoka S. 2004. Tax-independent constitutive IkappaB kinase activation in adult T-cell leukemia cells. Neoplasia 6:266–278. doi: 10.1593/neo.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahgoub M, Yasunaga JI, Iwami S, Nakaoka S, Koizumi Y, Shimura K, Matsuoka M. 2018. Sporadic on/off switching of HTLV-1 Tax expression is crucial to maintain the whole population of virus-induced leukemic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E1269–E1278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715724115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozden S, Cochet M, Mikol J, Teixeira A, Gessain A, Pique C. 2004. Direct evidence for a chronic CD8+-T-cell-mediated immune reaction to tax within the muscle of a human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type 1-infected patient with sporadic inclusion body myositis. J Virol 78:10320–10327. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10320-10327.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forlani G, Baratella M, Tedeschi A, Pique C, Jacobson S, Accolla RS. 2019. HTLV-1 HBZ protein resides exclusively in the cytoplasm of infected cells in asymptomatic carriers and HAM/TSP patients. Front Microbiol 10:819. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mori N, Fujii M, Ikeda S, Yamada Y, Tomonaga M, Ballard DW, Yamamoto N. 1999. Constitutive activation of NF-kappaB in primary adult T-cell leukemia cells. Blood 93:2360–2368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song X, Zhao Z, Qi X, Tang S, Wang Q, Zhu T, Gu Q, Liu M, Li J. 2015. Identification of epipolythiodioxopiperazines HDN-1 and chaetocin as novel inhibitor of heat shock protein 90. Oncotarget 6:5263–5274. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao L, Harhaj EW. 2013. HSP90 protects the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) tax oncoprotein from proteasomal degradation to support NF-kappaB activation and HTLV-1 replication. J Virol 87:13640–13654. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02006-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoogstraten D, Nigg AL, Heath H, Mullenders LH, van Driel R, Hoeijmakers JH, Vermeulen W, Houtsmuller AB. 2002. Rapid switching of TFIIH between RNA polymerase I and II transcription and DNA repair in vivo. Mol Cell 10:1163–1174. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00709-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao J, Grant C, Harhaj E, Nonnemacher M, Alefantis T, Martin J, Jain P, Wigdahl B. 2006. Regulation of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 gene expression by Sp1 and Sp3 interaction with TRE-1 repeat III. DNA Cell Biol 25:262–276. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.25.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhat NK, Adachi Y, Samuel KP, Derse D. 1993. HTLV-1 gene expression by defective proviruses in an infected T-cell line. Virology 196:15–24. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tagaya Y, Gallo RC. 2017. The exceptional oncogenicity of HTLV-1. Front Microbiol 8:1425. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin F, Tagaya Y, Gallo R. 2018. Time to eradicate HTLV-1: an open letter to WHO. Lancet 391:1893–1894. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30974-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caron C, Rousset R, Beraud C, Moncollin V, Egly JM, Jalinot P. 1993. Functional and biochemical interaction of the HTLV-I Tax1 transactivator with TBP. EMBO J 12:4269–4278. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hilario E, Li Y, Nobumori Y, Liu X, Fan L. 2013. Structure of the C-terminal half of human XPB helicase and the impact of the disease-causing mutation XP11BE. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69:237–246. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912045040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dassouki Z, Sahin U, El Hajj H, Jollivet F, Kfoury Y, Lallemand-Breitenbach V, Hermine O, de Thé H, Bazarbachi A. 2015. ATL response to arsenic/interferon therapy is triggered by SUMO/PML/RNF4-dependent Tax degradation. Blood 125:474–482. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-572750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hahn S. 2004. Structure and mechanism of the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11:394–403. doi: 10.1038/nsmb763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kouzine F, Wojtowicz D, Yamane A, Resch W, Kieffer-Kwon KR, Bandle R, Nelson S, Nakahashi H, Awasthi P, Feigenbaum L, Menoni H, Hoeijmakers J, Vermeulen W, Ge H, Przytycka TM, Levens D, Casellas R. 2013. Global regulation of promoter melting in naive lymphocytes. Cell 153:988–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rice AP. 2017. The HIV-1 Tat protein: mechanism of action and target for HIV-1 cure strategies. Curr Pharm Des 23:4098–4102. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170704130635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nasr R, Chiari E, El-Sabban M, Mahieux R, Kfoury Y, Abdulhay M, Yazbeck V, Hermine O, de Thé H, Pique C, Bazarbachi A. 2006. Tax ubiquitylation and sumoylation control critical cytoplasmic and nuclear steps of NF-kappaB activation. Blood 107:4021–4029. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perugi F, Muriaux D, Ramirez BC, Chabani S, Decroly E, Darlix JL, Blot V, Pique C. 2009. Human Discs Large is a new negative regulator of human immunodeficiency virus-1 infectivity. Mol Biol Cell 20:498–508. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-02-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mone MJ, Bernas T, Dinant C, Goedvree FA, Manders EM, Volker M, Houtsmuller AB, Hoeijmakers JH, Vermeulen W, van Driel R. 2004. In vivo dynamics of chromatin-associated complex formation in mammalian nucleotide excision repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:15933–15937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403664101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giglia-Mari G, Miquel C, Theil AF, Mari PO, Hoogstraten D, Ng JM, Dinant C, Hoeijmakers JH, Vermeulen W. 2006. Dynamic interaction of TTDA with TFIIH is stabilized by nucleotide excision repair in living cells. PLoS Biol 4:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]