Abstract

Interferons (IFNs) play an important role in immunomodulatory and antiviral functions. IFN-induced necroptosis has been reported in cells deficient in receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD), or caspase-8, but the mechanism is largely unknown. Here, we report that the DNA-dependent activator of IFN regulatory factors (ZBP1, also known as DAI) is required for both type I (β) and type II (γ) IFN-induced necroptosis. We show that L929 fibroblast cells became susceptible to IFN-induced necroptosis when RIPK1, FADD, or Caspase-8 was genetically deleted, confirming the antinecroptotic role of these proteins in IFN signaling. We found that the pronecroptotic signal from IFN stimulation depends on new protein synthesis and identified ZBP1, an IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) product, as the de novo synthesized protein that triggers necroptosis in IFN-stimulated cells. The N-terminal domain (ND) of ZBP1 is important for ZBP1–ZBP1 homointeraction, and its RHIM domain in the C-terminal region interacts with RIPK3 to initiate RIPK3-dependent necroptosis. The antinecroptotic function of RIPK1, FADD, and caspase-8 in IFN-treated cells is most likely executed by caspase-8-mediated cleavage of RIPK3, since the inhibitory effect on necroptosis was eliminated when the caspase-8 cleavage site in RIPK3 was mutated. ZBP1-mediated necroptosis in IFN-treated cells is likely physiologically relevant, as ZBP1 KO mice were significantly protected against acute systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) induced by TNF + IFN-γ.

Keywords: ZBP1, interferon, necroptosis

Subject terms: Cell signalling, Innate immunity

Introduction

Interferons (IFNs) are secreted proteins manufactured and released by cells in response to viral infection and other stimuli. Acting in paracrine or autocrine modes, IFNs stimulate intra- and inter-cellular networks regulating innate and acquired immunity, resistance to viral infections, and normal and tumor cell survival and death.1 IFNs are primarily divided into two distinct types: types I and II.2,3 Type I IFNs include various subtypes, of which IFN-α and IFN-β are the predominant forms.4 Type II IFN comprises a single cytokine, IFN-γ.3 After binding to a heterodimeric receptor consisting of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2,5 Type I IFNs activate the JAK-STAT signal transduction cascade involving TYK2, JAK1, STAT1, and STAT2,6 resulting in the production of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs).7 Type II IFN binds to the IFNγR receptor, which consists of IFN γR1 and IFN γR2 chains.8 IFN-γ activates JAK1, JAK2, and STAT1, leading to the transcription of downstream genes.7,9 Noticeably, the JAK1-STAT1 complex plays a role in both types I and II IFN signaling pathways. Recently, several studies have reported that IFNs are involved in necroptotic cell death, a type of programmed necrosis that depends on receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3)-MLKL necrosome formation. IFNs can induce necroptosis in RelA-deficient cells, suggesting that NF-κB blocks IFN-induced necroptosis in wild-type (WT) cells.10 IFNs can also induce necroptosis in RIPK1-, Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD)-, or caspase-8-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEFs).11,12 PKR, an RNA-activated protein kinase, is reported to be essential for IFN-induced necroptosis in FADD- or caspase-8-deficient cells.12 However, recent evidence indicates that PKR is not involved in necroptosis induced by IFNs + zVAD, a pan-caspase inhibitor, in macrophages.13 This study showed a role of IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex activation and the induction of downstream genes in sustaining RIPK3 activation and necroptosis in macrophages.13 These studies suggested the complexity of the mechanisms of IFN-induced necroptosis. Thus, further studies are needed.

ZBP1 is a Z-DNA-binding protein that can be induced by IFNs.14 The function of ZBP1 was originally shown to involve DNA-mediated antiviral responses through type I IFN induction and NF-κB activation.15 After binding to cytosolic DNA through its N-terminal domain (ND), ZBP1 recruits TBK1 and IRF3 to its C-terminal region to activate IFN production. However, ZBP1 knockout (KO) MEFs and bone marrow dendritic cells respond normally to B-DNA and DNA vaccines.16 Necroptosis induced by murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection was dependent on the expression of ZBP117 and on MCMV IE3-dependent transcription.18 ZBP1 could interact with the RNA of MCMV through its Z-binding domains.19 Moreover, ZBP1 might function in inducing necroptosis and apoptosis by directly binding to IAV genomic RNA.20 Recently, ZBP1 was reported to be involved in necroptosis induced by E3-Zα-domain-deleted vaccinia virus (VACV-E3LΔ83N).21 In necroptosis mediated by the SMAC mimetic LBW-242 and the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD, the induced PUMA promotes the release of cytosolic mtDNA to activate ZBP1, leading to enhanced RIPK3 and MLKL phosphorylation.22 ZBP1 is also involved in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in IAV-infected bone marrow-derived macrophages.23 Importantly, like RIPK1 and RIPK3, ZBP1 is an RHIM (RIP homotypic interaction motif) domain-containing protein, implying its potential role in associating with RIPK1 and RIPK3 to participate in necroptosis. Two recent studies revealed that ZBP1 plays a crucial role in RIPK1 RHIM mutation-induced inflammatory necroptosis by interacting with RIPK3.24,25

Here, we studied IFN-induced necroptosis using a number of genetically modified L929 fibroblast cell lines. Deletion of RIPK1, FADD, or Caspase-8 in L929 cells released the blockage of necroptosis, which allowed efficient necroptosis after treatment with either IFN-β or IFN-γ. We found that IFN-induced necroptosis requires de novo protein synthesis and that IFN-induced ZBP1 gene expression is essential for IFN-induced necroptosis. Different domains in ZBP1 are responsible for its homointeraction and its interaction with RIPK3, and both interactions are required for IFN-induced necroptosis. Studies of TNF signaling have already revealed that RIPK1, FADD, and caspase-8 form a complex in which caspase-8 is activated to cleave RIPK1 or RIPK3.26–28 We showed here that the inhibition of IFN-induced necroptosis by this complex is most likely a result of RIPK3 cleavage by caspase-8. Moreover, we found that depletion of ZBP1 in mice significantly protected the animals from systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) induced by TNF + IFN-γ. Taken together, these findings suggest that ZBP1 is the critical mediator of IFN-induced necroptosis and reveal the effect of the ZBP1-RIPK3 signaling cascade in necroptosis-related SIRS in vivo.

Results

IFN-β- and IFN-γ-induced necroptosis require de novo protein synthesis

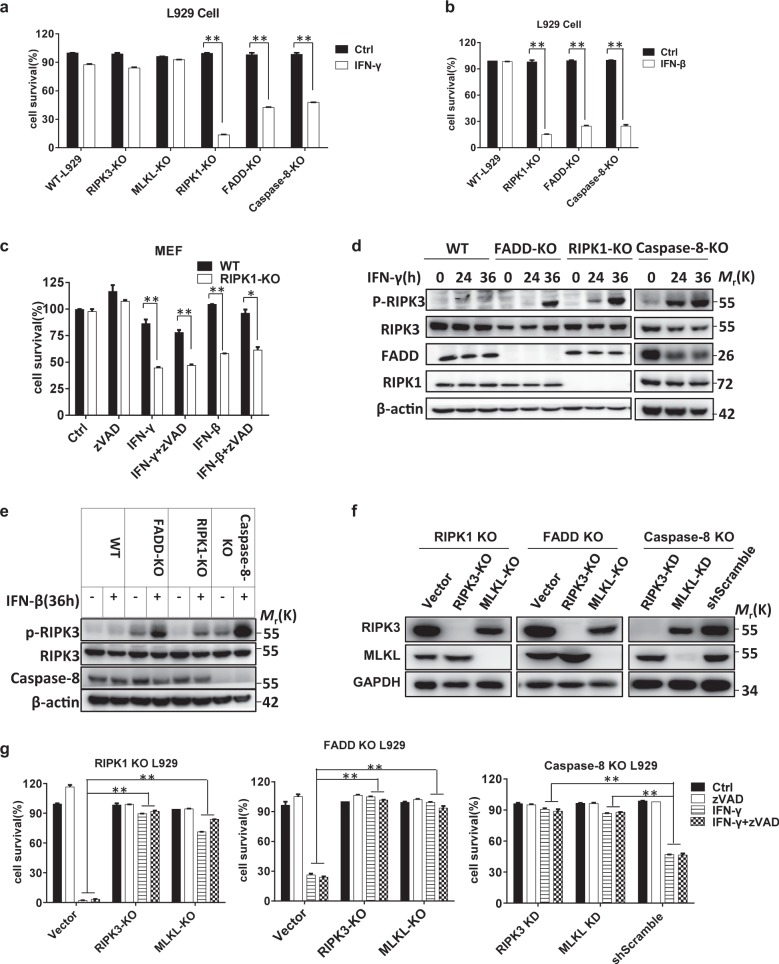

IFN-induced necroptosis has been reported in MEFs deficient in FADD or caspase-8,12 but conflicting conclusions were drawn on whether RIPK1 promotes or inhibits IFN-induced cell death.11,12,29,30 To verify the effect of FADD, caspase-8, and RIPK1 on IFN-triggered cell death, we investigated whether IFN can induce cell death in the corresponding L929 KO cell lines. Both IFN-β and IFN-γ induced cell death in FADD KO, caspase-8 KO, and RIPK1 KO cells but not in WT L929 cells (Fig. 1a, b). Additionally, IFN-γ-induced cell death was not affected by knockout of RIPK3 or MLKL (Fig. 1a), the two proteins required for necroptosis.31–34 We treated RIPK1 WT and KO MEFs with IFN-γ or IFN-β with or without the addition of zVAD and confirmed that IFN-induced cell death in RIPK1 KO cells could not be blocked by caspase inhibition (Fig. 1c), indicating that this type of cell death is a necroptotic process. As RIPK3 phosphorylation (on Thr231 and Ser232 in mouse RIPK3; on Ser 227 in human RIPK3) is a hallmark of necroptosis,31,35 we next examined RIPK3 phosphorylation in RIPK1 KO, FADD KO, and caspase-8 KO L929 cells after IFN treatment. As shown in Fig. 1d, e, phosphorylation of RIPK3 was detected, confirming that IFN-induced cell death is a necroptotic process. To further demonstrate the necroptotic nature of IFN-induced cell death, RIPK3, or MLKL double knockout (DKO) cells were generated from RIPK1 KO, FADD KO, and caspase-8 KO L929 cells (Fig. 1f). Treatment of these cells with IFN-γ or IFN-γ + zVAD showed that RIPK3 or MLKL deficiency completely blocked IFN-induced cell death in RIPK1 KO, FADD KO, and caspase-8 KO cells (Fig. 1g). Consistent with these findings, the RIPK3 inhibitor GSK872 efficiently suppressed IFN-γ-mediated cell death in these KO cells (Fig. S1a). To exclude the possibility that IFN-induced necroptosis is due to the autocrine effect of IFN-induced TNF, we knocked out RIPK1, FADD, or caspase-8 expression in TNFR1 KO cells36 and then treated the cells with zVAD, IFN-γ, IFN-γ + zVAD, or TNF-α. TNFR1 KO blocked TNF-induced necroptosis but not IFN-γ- or IFN-γ + zVAD-induced necroptosis (Fig. S1b–d). Collectively, these results show that IFNs induce necroptosis in L929 cells when RIPK1, FADD, or caspase-8 is inhibited.

Fig. 1.

IFN-β/γ induces necroptosis in RIPK1/FADD/caspase-8 deficient cells. a The indicated knockout L929 cell lines were treated with PBS (ctrl) or IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 36 h. Cell viability was determined by measuring the ATP levels. b The indicated knockout L929 cell lines were treated with PBS (ctrl) or IFN-β (1000 U/ml) for 36 h, and cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels. c WT and RIPK1 KO MEF cells were treated with DMSO (ctrl), zVAD (20 µM), IFN-γ, IFN-γ + zVAD, IFN-β, or IFN-β + zVAD, and cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels. d WT, FADD KO, RIPK1 KO, and caspase-8 KO L929 cells were treated with IFN-γ for the indicated time periods, and the indicated proteins were detected by western blotting. e WT, FADD KO, RIPK1 KO, and caspase-8 KO L929 cells were treated with IFN-β for 36 h, and the indicated proteins were detected by western blotting. f The RIPK3, MLKL, and GAPDH levels in the indicated knockout L929 cell lines were measured by western blotting. g The indicated knockout L929 cell lines were treated with IFN-γ and IFN-γ + zVAD for 36 h, and cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels. All the abovementioned error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. of three independent experiments. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied to determine the indicated P values. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. For d–f, the data shown are representative of the results of three independent experiments

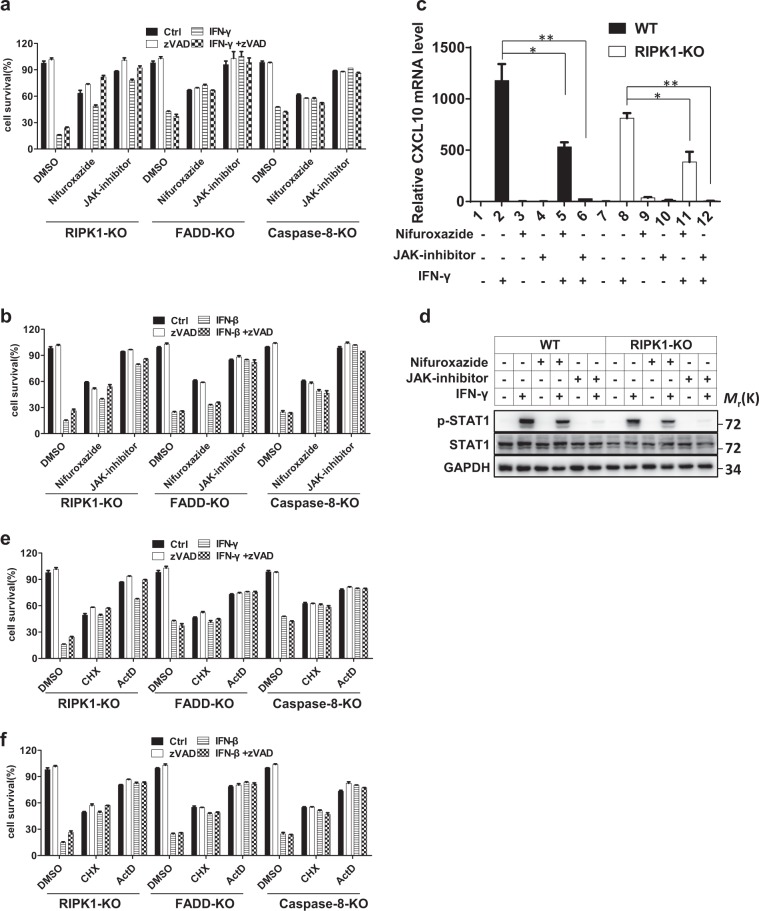

It is clear that IFNs induce the expression of ISGs through the JAK1-STAT1 pathway. Previous studies have revealed that IFN-induced cell death can be blocked in JAK1/STAT1 KO MEFs12 and depends on the ISGF3 complex.13 To determine whether the ISGs participate in IFN-induced necroptosis in our L929 cell systems, we utilized a JAK1 inhibitor and the STAT1 inhibitor nifuroxazide to inhibit the JAK1-STAT1 pathway in L929 cells deficient in RIPK1, FADD, or caspase-8 after IFN-γ or -β treatment. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, inhibition of the JAK1-STAT1 pathway compromised IFN-induced necroptosis, consistent with the previous finding. To confirm the inhibition efficiency of the JAK1 inhibitor and nifuroxazide, we measured the mRNA level of CXCL10, which is a well-known ISG, and found, as expected, that its induction was reduced by these two inhibitors in both WT and RIPK1 KO L929 cells after IFN-γ stimulation (Fig. 2c). We also evaluated the effect of these two inhibitors on the phosphorylation of STAT1 in WT and RIPK1 KO L929 cells under stimulation by IFN-γ and found that the JAK1 inhibitor and nifuroxazide decreased the phosphorylation of STAT1 (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

IFN-β/γ-induced cell death is dependent on the JAK1-STAT1 signaling pathway and de novo protein synthesis. a The indicated knockout L929 cell lines were treated with DMSO (ctrl), zVAD, IFN-γ, or IFN-γ + zVAD and nifuroxazide (50 µM) or a JAK inhibitor (1 µM) for 36 h, and cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels. b The indicated knockout L929 cell lines were treated with DMSO (ctrl), zVAD, IFN-β, or IFN-β + zVAD with or without nifuroxazide or a JAK inhibitor for 36 h, and cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels. c qRT-PCR analysis was performed to determine the relative CXCL10 mRNA level in WT and RIPK1 KO L929 cells treated with or without IFN-γ, nifuroxazide, or a JAK inhibitor. d WT and RIPK1 KO cells were treated with or without IFN-γ, nifuroxazide, or a JAK inhibitor for 36 h, and the indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. e The indicated knockout L929 cell lines were treated with DMSO (ctrl), zVAD, IFN-γ, or IFN-γ + zVAD and with CHX (10 µg/ml) and ActD (1 µg/ml) for 36 h, and cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels. f The indicated knockout L929 cell lines were treated with DMSO (ctrl), zVAD, IFN-β, or IFN-β + zVAD and with CHX and ActD for 36 h, and cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels. The quantitative data shown are from n = 3 independent experiments. The error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. of n = 3 independent experiments. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied to determine the indicated P values. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. For d, the data shown are representative of three independent experiments

Since JAK1/STAT1 pathway activation results in ISG production, we reasoned that the production of certain ISGs might account for IFN-induced necroptosis. To verify this hypothesis, we inhibited gene transcription and translation with actinomycin D (ActD) and cycloheximide (CHX), respectively, and then examined IFN-β- or γ-induced necroptosis in RIPK1-, FADD-, and caspase-8-deficient L929 cells. As anticipated, IFN-induced cell death could be blocked by both CHX and ActD treatment, suggesting that de novo protein synthesis is required for IFN-induced necroptosis (Fig. 2e, f).

ZBP1 is required for IFN-induced necroptosis

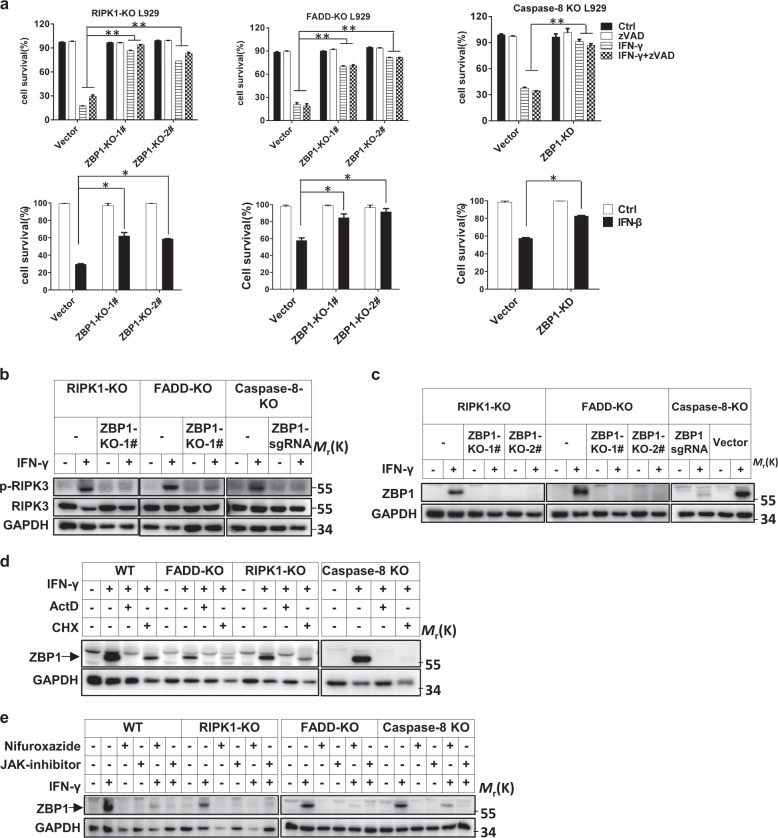

In searching for the de novo synthesized protein(s) required for IFN-induced necroptosis, we identified ZBP1, since the expression of ZBP1 is inducible by IFNs and ZBP1 has been reported to mediate RIPK3/MLKL-dependent necroptosis.24,25,37 We knocked out or knocked down ZBP1 expression in RIPK1 KO, FADD KO, and caspase-8 KO L929 cells and then determined the responses of these cells to IFN-γ or IFN-β (Fig. 3a). Impressively, IFN-induced necroptosis was blocked. However, we found that knockout of PKR, an ISG that was reported to promote the phosphorylation of RIPK1 and RIPK3 in IFN-γ-treated cells,12 did not invoke any resistance to IFN-γ- or IFN-γ + zVAD-induced necroptosis (Fig. S2a-2c).

Fig. 3.

ZBP1 is required for IFN-induced necroptosis. a The indicated knockout L929 cell lines were treated with DMSO (ctrl), zVAD, IFN-γ, IFN-γ + zVAD, or IFN-β, and cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels. b The p-RIPK3, RIPK3, and GAPDH protein levels in the indicated cells treated with or without IFN-γ for 36 h were measured by western blotting. The cells marked “ZBP1 sgRNA” were pooled ZBP1 KO cells, not isolated single clones of KO cells. c The ZBP1 and GAPDH protein levels in indicated cells treated with or without IFN-γ were measured by western blotting. d The ZBP1 and GAPDH protein levels in the indicated cells treated with or without IFN-γ, ActD, or CHX were measured by western blotting. e The ZBP1 and GAPDH protein levels in the indicated cells treated with or without IFN-γ, nifuroxazide, or a JAK inhibitor were measured by western blotting. For a, the data are from n = 3 independent experiments. The error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. of n = 3 independent experiments. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied to determine the P values. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. For b–e, the results shown are representative of the results of three independent experiments

We then further evaluated the role of ZBP1 in IFN-γ-induced necroptosis. The induction of RIPK3 phosphorylation by IFN-γ stimulation was blocked in ZBP1-deficient cells (Fig. 3b, c). IFN-γ-induced necroptosis and ZBP1 expression were effectively blocked by ActD, CHX, and the JAK inhibitor (Figs. 2 and 3d, e), supporting the hypothesis that blockade of ZBP1 induction leads to inhibition of IFN-γ-induced necroptosis. Combining these findings, we conclude that ZBP1, which is induced by IFN-γ via the JAK1/STAT1 signaling pathway, is necessary for IFN-γ-induced necroptosis.

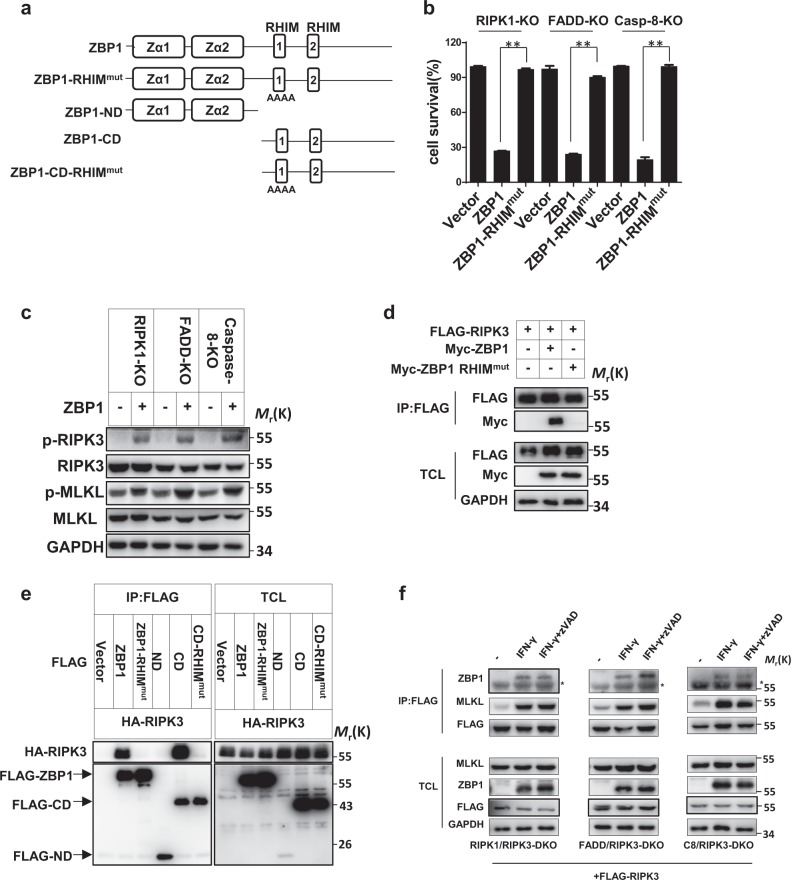

RHIM-dependent interaction between ZBP1 and RIPK3 is essential for IFN-induced necroptosis

ZBP1 has two RHIM domains (Fig. 4a),24,25 and previous studies by others showed that only the first RHIM domain can mediate the interaction between ZBP1 and RIPK1 or RIPK3.38,39 As it has been reported that RHIM domain-containing viral proteins can mediate necroptosis mediated by interactions with RIPK3 via the RHIM domain,36 IFN-induced ZBP1 might also interact with RIPK3 through its RHIM domains. To evaluate this possibility, we first overexpressed ZBP1 in RIPK1 KO, FADD KO, and caspase-8 KO L929 cells and examined cell viability and the RIPK3 phosphorylation levels. ZBP1 overexpression induced cell death and promoted RIPK3 and MLKL phosphorylation in those L929 cells. We then overexpressed a ZBP1-RHIMmut protein containing a mutation in the first RHIM domain (IQIG192-195AAAA) and found that this protein could not induce necroptosis (Fig. 4b, c). These data suggest that ZBP1 induces necroptosis in an RHIM-dependent manner.

Fig. 4.

RHIM-dependent interaction between ZBP1 and RIPK3 is essential for IFN-induced necroptosis. a Schematics illustrating the domains of ZBP1 and the ZBP1 RHIMmut mutant. b The indicated knockout L929 cell lines were infected with lentivirus expressing blank vector (Vector) or vectors encoding ZBP1 or ZBP1 RHIMmut, and cell survival at 24 h after infection was determined by measuring the ATP levels. c The p-RIPK3, RIPK3, p-MLKL, MLKL, and GAPDH protein levels in cells infected with lentivirus expressing blank vector or vectors encoding ZBP1 or its mutants were measured by western blotting. d A total of 293T cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated for 48 h. Total cell lysates (TCL) and anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted to detect the indicated proteins. e A total of 293T cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated for 48 h. TCL and anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted to detect the indicated proteins. f The indicated knockout L929 cell lines were transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG-RIPK3 and were then treated with or without IFN-γ or IFN-γ + zVAD for 36 h. TCL and anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted to detect the indicated proteins. For a, the data are from n = 3 independent experiments. The error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. of n = 3 independent experiments. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied to determine the P values. **P < 0.01. For b, c, e, and f, the results shown are representative of the results of three independent experiments

We then investigated whether ZBP1 can interact with RIPK3. Flag-RIPK3 was coexpressed with Myc-ZBP1 or Myc-ZBP1-RHIMmut in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells. Myc-ZBP1 but not Myc-ZBP1-RHIMmut was detected in the Flag-RIPK3 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 4d). We also generated N-terminal domain (ND) and C-terminal domain (CD) truncations of ZBP1, as well as a CD containing the first RHIM mutation (Fig. 4a) and evaluated their interactions with RIPK3 (Fig. 4e). The above ZBP1 mutants were coexpressed with HA-RIPK3 in HEK 293T cells, and coimmunoprecipitation revealed that the CD in ZBP1 depends on the first RHIM domain to interact with RIPK3 (Fig. 4e). Necrosome formation is a hallmark of necroptosis, and we further examined whether ZBP1 is involved in IFN-induced necrosome formation. We generated RIPK1/RIPK3 DKO, FADD/RIPK3 DKO, and caspase-8/RIPK3 DKO L929 cells and then reconstituted RIPK3 expression in the DKO cells via a Flag-tagged RIPK3 lentiviral vector. By treating the cells with IFN-γ or IFN-γ + zVAD, we confirmed that Flag-RIPK3 complementation restored the sensitivity of DKO cells to IFN-induced necroptosis (Fig. S3a, b). In the complemented cells, we detected an interaction between RIPK3 and MLKL upon treatment with IFN-γ or IFN-γ + zVAD, indicating the formation of necrosomes (Fig. 4f). Additionally, we found that ZBP1 associated with RIPK3 to participate in the necrosome formation process (Fig. 4f). Collectively, our data demonstrated that IFN-γ can induce formation of the ZBP1-RIPK3-MLKL multiprotein complex, which leads to necroptosis.

ZBP1 homointeraction is important in triggering RIPK3-dependent necroptosis

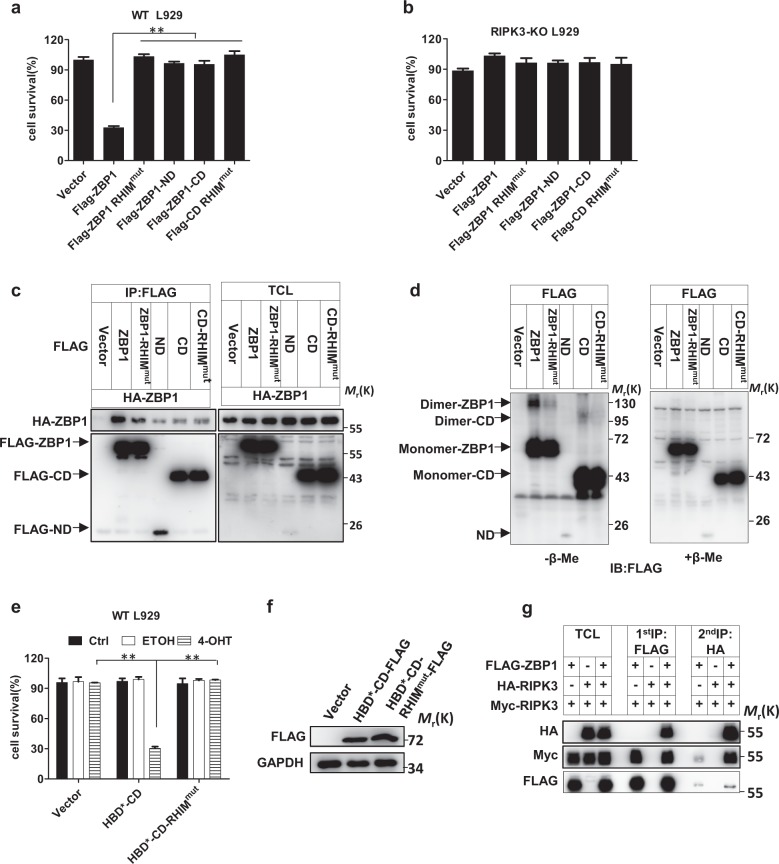

Since the CD of ZBP1 is sufficient for interaction with RIPK3 (Fig. 4e), we assessed the effect of WT ZBP1, ZBP1-RHIMmut, ZBP1-ND, ZBP1-CD, and ZBP1-CD-RHIMmut overexpression on initiating necroptosis. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, only WT ZBP1 elicited RIPK3-dependent necroptosis in L929 cells. Ectopically overexpressed ZBP1 seemed to be more cytotoxic than IFN-induced ZBP1; when the level of ectopic ZBP1 was comparable with that of IFN-induced ZBP1, cell death was observed in ZBP1-overexpressing cells but not in IFN-γ-treated cells (Fig. S4a). Therefore, the induction of ZBP1 by IFN is not the sole factor that controls IFN-induced necroptosis. As it is known that RIPK3 homointeractions can trigger necroptosis40 and that ZBP1 can directly interact with RIPK3 (Fig. 4d), we investigated whether ZBP1 forms dimers/oligomers in eliciting necroptosis. We coexpressed Flag-tagged ZBP1 with HA-tagged ZBP1 in HEK 293T cells and carried out a coimmunoprecipitation assay. We found that Flag-ZBP1 associated with HA-ZBP1 and that the homointeraction of ZBP1 was dependent on its ND, CD, and RHIM domain (Fig. 5c). We analyzed HEK 293T cells expressing ZBP1 and its mutants by western blotting under reducing and nonreducing conditions and detected disulfide bond-linked ZBP1 homocomplexes. The homointeraction intensity decreased when the ND was deleted or the RHIM domain was mutated (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

ZBP1 homointeraction is important in triggering RIPK3-dependent necroptosis. a, b WT L929 or RIPK3 KO L929 cells were infected with lentiviral vector to express proteins as indicated, and cell survival was determined at 36 h after infection by measuring the ATP levels. c A total of 293T cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. TCL and anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted to detect the indicated proteins. d A total of 293T cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. TCL and anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates were treated with or without β-mercaptoethanol (β-Me) and immunoblotted to detect the indicated proteins. e WT L929 cells were infected with lentiviral vectors to express proteins as indicated and were then treated with PBS (ctrl), ethanol (ETOH), or 4-OHT for 12 h; cell survival was then determined by measuring the ATP levels. f WT L929 cells were infected with lentiviral vectors to express proteins as indicated. The FLAG and GAPDH protein levels were measured by western blotting. g A total of 293T cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated, and sequential immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag antibody and anti-HA antibody was performed. TCL and the anti-FLAG and sequential anti-HA immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted to detect the indicated proteins. For a, b, and e, the data are from n = 3 independent experiments. The error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. of n = 3 independent experiments. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied to determine the P values. **P < 0.01. For c, d, f, and g, the results shown are representative of the results of three independent experiments

Since the ZBP1-CD alone cannot trigger cell death even though it can interact with RIPK3, it is possible that the ND in ZBP1 plays an important role in the interaction between ZBP1 proteins and that the ZBP1-CD is responsible for the initiation of RIPK3 homointeraction by the ZBP1 complex. To test this hypothesis, we sought to determine whether artificial dimers of ZBP1-CD would lead to necroptotic cell death. The dimerization/oligomerization system used in our experiments was based on 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT)-induced homodimerization of a hormone-binding domain G521R mutant (HBD*) of the estrogen receptor.41 We fused HBD* to the ZBP1-CD (termed HBD*-CD) or ZBP1-CD RHIM mutant (termed HBD*-CD RHIMmut) and expressed these fusions in WT L929 cells. The protein expression levels were determined by immunoblotting (Fig. 5f). After the addition of 4-OHT, cells expressing HBD*-CD underwent cell death, whereas control cells did not (Fig. 5e), demonstrating that the HBD*-mediated interaction of ZBP1-CD is sufficient to trigger cell death. As anticipated, the RHIM domain of ZBP1-CD was required for its function, as 4-OHT did not induce the death of cells expressing HBD*-CD RHIMmut (Fig. 5e). We also compared the ZBP1 levels in cells overexpressing FLAG-HBD-CD with those in cells treated with IFN-γ and found that dimeric ZBP1 could kill WT cells at a much lower protein level than monomeric ZBP1 (Fig. S4b), supporting the hypothesis that homooligomerization of ZBP1 initiates necroptotic signaling. We further performed a sequential coimmunoprecipitation experiment to verify the function of ZBP1 in mediating the RIPK3 homointeraction. We first pulled down FLAG-containing proteins from cell lysates containing FLAG-ZBP1, Myc-RIPK3 and/or HA-RIPK3. Both HA-RIPK3 and Myc-RIPK3 coimmunoprecipitated with Flag-ZBP1 (Fig. 5g). Subsequently, we utilized anti-HA beads to pull down HA-RIPK3 from the 3 × Flag peptide-eluted solution obtained in the first round of immunoprecipitation and detected Myc-RIPK3 (Fig. 5g). Thus, the ZBP1-RIPK3-RIPK3 complex was present.

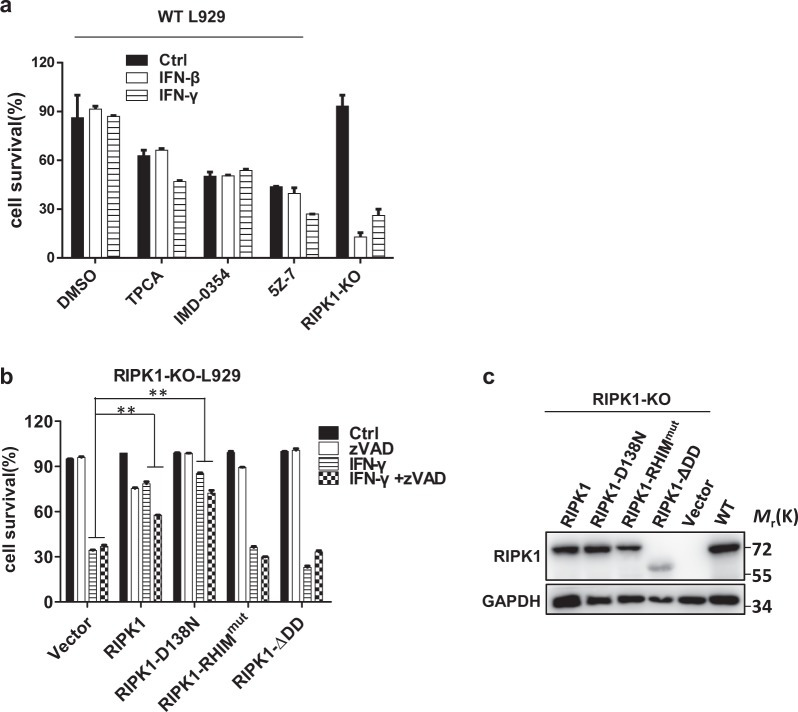

Kinase activity is not required for RIPK1 to inhibit IFN-γ-induced cell death, but the RHIM domain is essential

A number of reports have shown that RIPK1 kinase activity plays an important role in mediating TNF-induced necroptosis via autophosphorylation, allowing the efficient recruitment of RIPK3 via the RHIM domain to form a functional necrosome.37 In addition to this role, RIPK1 also plays an important role in stimulating NF-κB activation, which is crucial for survival signaling.42,43 To investigate the means by which RIPK1 performs its inhibitory function in IFN-induced necroptosis, we first investigated whether NF-κB signaling is required by using different inhibitors. The IKKα/IKKβ inhibitor TPCA/IMD-0354 and the TAK1 inhibitor 5Z-7 were added to IFN-β/γ-treated WT L929 cells, and cell viability was determined. As shown in Fig. 6a, treatment with IFN-β/γ efficiently induced necroptosis in RIPK1 KO L929 cells but not in WT cells in the presence of IKK/TAK1 inhibitors, indicating that NF-κB activation is not involved in the inhibition of IFN-induced necroptosis by RIPK1. We next reconstituted RIPK1 expression in RIPK1 KO L929 cells via WT RIPK1, RIPK1-D138N (a kinase-dead mutant), RIPK1 RHIMmut (an RHIM domain mutant), and RIPK1-ΔDD (a death domain deletion mutant) lentiviral vectors (Fig. 6c) and examined cell death after treatment with IFN-γ or IFN-γ + zVAD. We found that WT RIPK1 and RIPK1-D138N but not RIPK1 RHIMmut or RIPK1-ΔDD effectively restored the inhibitory effect of RIPK1 on IFN-γ-induced necroptosis (Fig. 6b). Since the expression level of RIPK1-ΔDD was relatively lower than that of the other proteins, the role of the RIPK1 death domain in IFN-γ-induced necroptosis needs to be further clarified. The RIPK1 kinase inhibitor Nec-1 was reported to suppress necroptosis in FADD KO MEFs treated with IFN-γ and WT MEFs treated with IFN-γ + zVAD.12 However, in contrast to the previous report, we could not detect a preventive effect of Nec-1 on IFN-γ−induced cell death in FADD KO or C8 KO L929 cells (Fig. S5a). Cell type specificities might account for the observed differences between L929 and MEF cells. Regarding the means by which IFN stimulation signals to RIPK1, we found that RIPK1 could interact with JAK1 and STAT1 in HEK 293T cells (Fig. S5b). Whether and how this interaction functions in IFN-induced cell death await further investigation. Collectively, these findings suggest that the suppressive effect of RIPK1 on IFN-induced necroptosis is dependent on its RHIM domain but not its kinase activity.

Fig. 6.

Kinase activity is not required for RIPK1 to inhibit IFN-γ-induced cell death, but the RHIM domain is essential. a WT L929 cells were treated with PBS (ctrl), IFN-γ, or IFN-β, and the indicated reagents for 36 h, and cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels. b The RIPK1 KO L929 cell lines infected with lentiviral vector to express the indicated proteins were treated with DMSO (ctrl), zVAD, IFN-γ, or IFN-γ + zVAD for 36 h, and cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels. c RIPK1 KO L929 cell lines were infected with lentiviral vector to express the indicated proteins. The RIPK1 and GAPDH protein levels were determined by western blotting. For a, b, the data are from n = 3 independent experiments. The error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. of n = 3 independent experiments. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied to determine the P values. **P < 0.01. For c, the results shown are representative of the results of three independent experiments

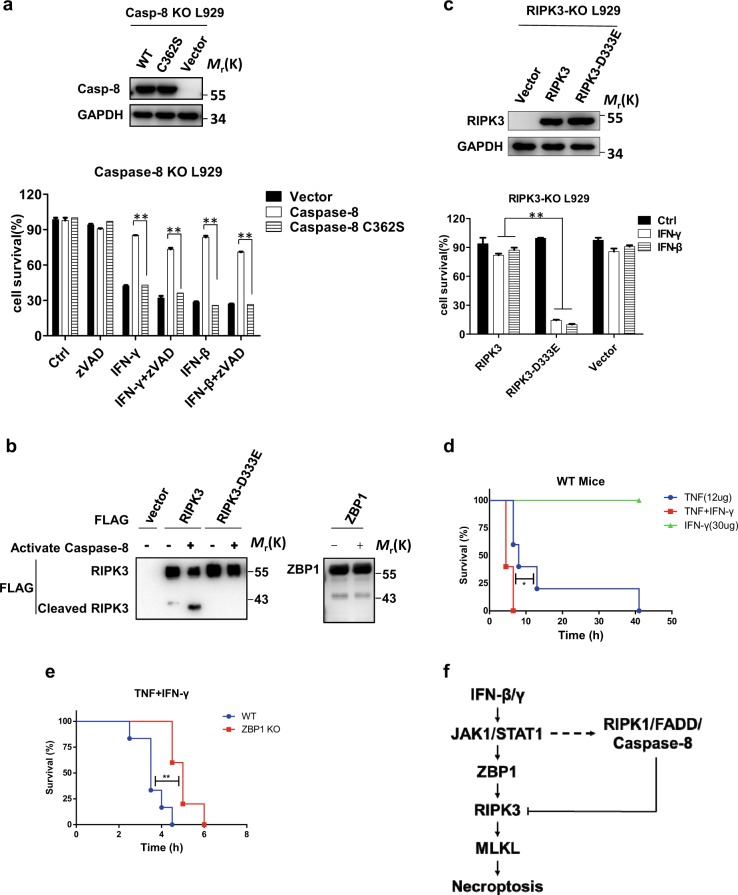

The caspase-8-resistant RIPK3 mutant enhances IFN-induced necroptosis

Previous reports have shown that caspase-8 acts as an important negative regulator in RIPK3-mediated necroptosis.26 To test whether caspase-8 inhibited IFN-γ/β-induced necroptosis through its protease activity, we constructed a caspase-8-C362S mutant in which cysteine 362 was mutated to serine. This loss-of-function mutant and WT caspase-8 were expressed in caspase-8 KO L929 cells. WT caspase-8 but not the caspase-8 C362S mutant restored the resistance of L929 cells to IFN-induced necroptosis (Fig. 7a). Since sequence analysis suggests that RIPK3 can be cleaved at D333 by caspase-8, we overexpressed FLAG-RIPK3 or the FLAG-RIPK3 D333E mutant in HEK 293T cells and purified the protein by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG M2 beads. As shown in Fig. 7b, FLAG-RIPK3 was cleaved to generate a fragment of ~40 KD by recombinant active caspase-8, but the FLAG-RIPK3 D333E mutant and ZBP1 were resistant to cleavage by caspase-8 under the same conditions. Perhaps the amount of cleaved RIPK3 in IFN-treated cells was very low or the cleaved product was unstable, but we could not detect cleaved endogenous RIPK3 in WT L929 cells. We next compared the ability of RIPK3-D333E with that of WT RIPK3 to mediate IFN-induced necroptosis by expressing them individually in RIPK3 KO cells. As shown in Fig. 7c, RIPK3-D333E effectively mediated IFN-induced necroptosis, whereas WT RIPK3 did not. This result further verifies the hypothesis that the inhibitory effect of caspase-8 on IFN-induced necroptosis is due to its cleavage of RIPK3 at the D333 site.

Fig. 7.

The caspase-8-resistant RIPK3 mutant enhances IFN-induced necroptosis, and ZBP1 KO mice are protected against SIRS induced by TNF + IFN-γ. a Caspase-8 KO L929 cell lines were infected with lentivirus expressing blank vector or vectors encoding caspase-8 or caspase-8 C362S and were treated with the indicated reagents for 36 h. Cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels (bottom). Top: The caspase-8 and GAPDH protein levels in the cells described above were measured by western blotting. b FLAG-RIPK3, FLAG-RIPK3-D333E, and FLAG-ZBP1 were overexpressed in 293T cells and were then immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody. After incubation with recombinant active caspase-8 at 37 °C for 2 h, western blotting was used to detect the indicated proteins. c RIPK3 KO L929 cell lines were infected with lentivirus expressing blank vector or vectors encoding RIPK3 or RIPK3-D333E and were then treated with IFN-γ or IFN-β for 36 h. Cell survival was determined by measuring the ATP levels (bottom). Top: The RIPK3 and GAPDH protein levels in the cells described above were measured by western blotting. For a, c, the data are from n = 3 independent experiments. The error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. of n = 3 independent experiments. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied to determine the P values. **P < 0.01. For a–c, the results shown are representative of the results of three independent experiments. d WT mice were injected with 12 µg TNF, 30 µg IFN-γ, or TNF + IFN-γ via the tail vein. Mouse survival is presented as a Kaplan–Meier plot, and the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was performed. N = 6 mice for each group. The data are pooled from two independent experiments. *P < 0.05. e Age- and sex-matched WT and ZBP1 KO mice were injected with TNF + IFN-γ through the tail vein. Mouse survival is presented as a Kaplan–Meier plot, and the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was performed. N = 6 mice for each group. The data are pooled from two independent experiments. **P < 0.01

ZBP1 KO mice are protected against SIRS induced by TNF + IFN-γ

Necroptosis induced by TNF is required for TNF-induced SIRS, used as a mouse model of sterile sepsis.44,45 It has been reported that IFNAR KO mice were resistant to TNF + IFN-γ-induced lethality in a melanoma tumor model.46 To investigate the role of ZBP1 in IFN-related physiological functions in vivo, we used IFN-γ cotreatment in a TNF-induced SIRS mouse model. As shown in Fig. 7d, intravenous injection of WT mice with mTNF resulted in mortality within 40 h, whereas all mice succumbed to TNF + IFN-γ treatment within 10 h. These results revealed that IFN-γ could sensitize mice to TNF-induced SIRS. We generated ZBP1 KO mice using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene targeting in mouse zygotes (Fig. S6a, b). The mortality rate appeared to be the same between WT and ZBP1 KO mice in response to TNF challenge (Fig. S6c). We further examined the role of ZBP1 in SIRS induced by TNF + IFN-γ and found that ZBP1 KO mice were significantly protected against SIRS induced by TNF + IFN-γ (Fig. 7e). In conclusion, these findings suggest that ZBP1 is important for IFN-γ-induced inflammatory responses in vivo.

Discussion

Necroptosis has been well studied in recent years. In addition to the well-known inducer TNF-α, various immunostimulatory and cell stress pathways converge to stimulate the formation of the RIPK3-MLKL necrosome complex.47,48 IFNs are crucial immunomodulatory factors that participate in antiviral infection and immune responses. However, the precise molecular mechanisms of IFN-induced necroptosis remain obscure. In this study, we showed that the pronecroptotic function of IFN-β and IFN-γ is mediated by IFN-induced ZBP1 (Fig. 3). The ZBP1 ND mediates its homointeraction, and its C-terminal RHIM domain interacts with RIPK3 to induce necroptosis upon IFN treatment (Figs. 4 and 5). The inhibitory effect of the RIPK1-FADD-caspase-8 complex on IFN-induced necroptosis is likely mediated by caspase-8 protease activity, since the protease-dead caspase-8 mutant did not inhibit IFN-induced necroptosis (Fig. 7a). Caspase-8 could target either ZBP1 or RIPK3 to inhibit IFN-induced necroptosis, but we showed that only RIPK3 can be cleaved by caspase-8 (Fig. 7b). The failure of the RIPK3-D333E mutant to maintain the inhibitory effects of the RIPK1-FADD-caspase-8 complex further support the hypothesis that caspase-8-mediated cleavage of RIPK3 inhibits IFN-induced necroptosis. Although we cannot formally conclude that the inhibition of TNF + IFN-γ-induced SIRS by ZBP1 deletion resulted solely from the reduction in necroptosis, IFN-induced necroptosis should be able to occur in vivo under certain circumstances, such as when caspase-8 is not expressed in cells.53,54 A proposed model of IFN-induced necroptosis is shown in Fig. 7f.

ZBP1 overexpression directly triggered cell death in WT cells,37 but IFNs did not induce cell death in WT cells (Fig. 1a). It appears that IFN-induced ZBP1 is inhibited by RIPK1/FADD/caspase-8, but ectopically expressed ZBP1 is not. It is possible that IFN can trigger the formation of the RIPK3-RIPK1-FADD-caspase-8 complex when RIPK3 is cleaved by caspase-8, but ectopically expressed ZBP1 without IFN treatment can directly interact with RIPK3.

RIPK1 has pro- and anti-cell death functions in both necroptosis and apoptosis. RIPK1 kinase activity triggers caspase-8-dependent apoptosis and RIPK3-dependent necroptosis.28,32,33,49,50 RIPK1 inhibits apoptosis and necroptosis in a kinase-independent manner, which is important for late embryonic development and the prevention of inflammation in epithelial barriers.11,25,29,30,51,52 Two recent studies showed that RIPK1 RHIM mutation led to ZBP1-dependent necroptotic disease in mice,24,25 indicating that RIPK1 inhibits ZBP1 signaling through its RHIM domain. Consistent with these findings, our results show that RIPK1 suppresses IFN-induced necroptosis via its RHIM domain but not its kinase domain (Fig. 6b). However, we could not detect competition between RIPK1 and RIPK3 for interaction with ZBP1 (data not shown). Moreover, the death domain of RIPK1 is indispensable for its inhibitory effect, most likely because this domain is required for interaction with FADD.

In summary, our data showed that IFN-induced necroptosis is mediated by ZBP1 induction and that RIPK1, FADD, and caspase-8 form an inhibitory complex to suppress the necroptotic process by cleaving RIPK3. Moreover, ZBP1-mediated necroptosis is involved in acute SIRS induced by TNF + IFN-γ in vivo. Our study revealed the molecular mechanism underlying IFN-β- and IFN-γ-induced necroptosis and suggested ZBP1 as a potential therapeutic target for systemic inflammatory disease.

Materials and methods

Cells lines and cell culture

Mouse fibrosarcoma L929 and HEK 293T cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). RIPK1 KO, FADD KO, Caspase-8 KO, and other gene KO L929 cell lines were constructed by the TALEN or CRISPR/Cas9 method. RIPK1 KO, RIPK3 KO, and MLKL KO L929 cells were generated as described.41 TNFR1 KO and ZBP1 KO L929 cells were generated as previously described.36 The RIPK1/RIPK3 DKO L929 cells were described previously.55 The targeting sequences were as follows: RIPK1—5′-AGAAGAAGGGAACTATTCGC-3′;

FADD—TGGAGCTCAAGTTCTTGTGCCGCGAGCGCGTGAGCAAACGAAAGCTGGA; Caspase-8—GCTGGTCAACTTCCTAGAC; TNFRI—5′-GCTTCAACGGCACCGTGACA-3′; ZBP1—5′-AAGATCTACCACTCACGTC-3′; RIPK3—5′-CTAACATTCTGCTGGA-3′; MLKL—5′-ATCATTGGAATACCGT-3′; and PKR—5′ GTGATACCCCAGGTTTCTAC-3′. The KO cells were confirmed by sequencing of the targeted loci, and the sequencing results are shown in Figs. S6 and S7. L929, HEK 293T, and MEF cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (vol/vol) (HyClone, USA), 2 mM l-glutamine (Millipore, USA), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Gibco, USA), 100 IU penicillin (Sangon, China) and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Sangon, China) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2.

Cell death assay

Cell death was analyzed by using a CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 4 × 104 cells were seeded in 96-well plates with white walls (Nunc). After 12 h, the cells were treated with reagents for the indicated durations. Then, an equal volume of CellTiter-Glo reagent was added to the cell culture medium before the medium was equilibrated to room temperature for 30 min. Cells were shaken for 15 min and rested for 5 min. Luminescence recording was performed with a POLARstar Omega (BMG Labtech, Durham, NC, USA).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

For Flag immunoprecipitation, cells were scraped and lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 1 mM Na3VO4) supplemented with Sigma Protease Inhibitor Cocktail. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation with mouse anti-Flag M2 beads at 4 °C overnight. After binding, the beads were washed three times with lysis buffer. The immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted with sample buffer, boiled for 10 min at 100 °C and analyzed by western blotting.

Reagents and antibodies

Antibodies against ZBP1 (M-300) (sc-67258), GAPDH (6C5), Myc (sc-40), HA (sc-805), and actin (sc-47778) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies against RIPK3, p-RIPK3, FADD, and MLKL were generated as described previously.56 The anti-RIPK1 antibody (610459) was purchased from BD Biosciences. The anti-caspase-8 (4790S) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. The anti-STAT1 (A0027) and anti-p-STAT1 (phospho Y701) (AP0135) antibodies were purchased from ABclonal. The anti-PKR (18244-1-AP) antibody was purchased from Proteintech. p-MLKL (phospho S345) (ab196436-100 µl) was purchased from Abcam. Mouse anti-FLAG M2 beads and anti-FLAG antibody (F2555-200 UL) were purchased from Sigma. Benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethylketone (zVAD) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA).

Plasmid construction

The full-length sequences of ZBP1, RIPK3, RIPK1, caspase-8, MLKL, JAK1, and STAT1 were amplified from our cDNA library. ZBP1 mutations (RHIM1Mut and RHIM2Mut), RIPK3 mutations (D143N, 2 A, RHIM*, and D333E), RIPK1 mutations (D138N and RHIM*), and the caspase-8 mutation (C362S) were introduced by two-round PCR. Gene truncations, including ZBP1-ND, ZBP1-CD, and RIPK1-ΔDD, were introduced by standard PCR using the corresponding full-length templates. Similarly, to generate fusion proteins, HBD* (G521R), ZBP1-CD, and ZBP1-CD-RHIM1Mut were amplified by standard PCR from the corresponding templates. All of these DNA fragments were cloned into pBOBI or pLV lentiviral vectors with no tag or Flag/HA/Myc tags. The Exo III-assisted ligation-independent cloning method was used for subcloning. All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

Lentivirus preparation and infection

A total of 293T cells were cotransfected with pBOBI constructs and lentiviral packaging plasmids (PMDL/REV/VSVG) by calcium phosphate precipitation. Fresh medium was replaced after 12 h. The lentivirus-containing supernatant was collected 36 h later and used for infection with 10 μg/ml polybrene. Plates were centrifuged at 1500 × g for 30 min and returned to the cell incubator. The infectious medium was changed 12 h later.

Generation of ZBP1−/− mice

ZBP1 KO mice were generated by comicroinjection of in vitro-translated Cas9 mRNA and gRNA into C57BL/6 zygotes. ZBP1 KO mice were validated by sequencing. The gRNA sequence used to generate the KO mice was 5′-AAGATCTACCACTCACGTC-3′. All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Xiamen University.

SIRS mouse model

Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Xiamen University Laboratory Animal Center. All animal experiments were conducted in compliance with the regulations of Xiamen University. Six- to eight-week-old male mice were injected intravenously with 12 µg TNF or 30 µg IFN-γ or TNF + IFN-γ diluted in endotoxin-free PBS. Animals were under permanent observation, and survival was assessed every 30 min. Littermates of ZBP1−/− and WT mice were used in the experiments. Mouse studies were performed in a blinded fashion.

Statistical evaluation

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism software (GraphPad Software). Data are presented as the means ± s.e.m. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare differences between treated groups and their paired controls. Mouse survival is presented as a Kaplan–Meier plot, and the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was performed. Differences in compared groups with P values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Supplementary information

ZBP1 mediates interferon-induced necroptosis-supplementary

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81788101), the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program 2015CB553800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31420103910, 81630042, 31500737, and 31601122), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018T110638, 2017 M620267, and 2015T80680), the 111 Project (B12001), and the National Science Foundation of China for Fostering Talents in Basic Research (J1310027).

Author Contributions

D. Y., Y. L., and J. H. conceived the study and wrote the manuscript; D. Y., S. Z., Y. D., and Q. Z. performed experiments; Q. S., T. A., and S. W. provided technical assistance.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Daowei Yang and Yaoji Liang

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41423-019-0237-x) contains supplementary material.

References

- 1.Vilcek J. Fifty years of interferon research: aiming at a moving target. Immunity. 2006;25:343–8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honda K, Takaoka A, Taniguchi T. Type I interferon [corrected] gene induction by the interferon regulatory factor family of transcription factors. Immunity. 2006;25:349–60. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pestka S, Krause CD, Walter MR. Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol. Rev. 2004;202:8–32. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Boxel-Dezaire AH, Rani MR, Stark GR. Complex modulation of cell type-specific signaling in response to type I interferons. Immunity. 2006;25:361–72. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piehler J, Thomas C, Garcia KC, Schreiber G. Structural and dynamic determinants of type I interferon receptor assembly and their functional interpretation. Immunol. Rev. 2012;250:317–34. doi: 10.1111/imr.12001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcello T, et al. Interferons alpha and lambda inhibit hepatitis C virus replication with distinct signal transduction and gene regulation kinetics. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1887–98. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:20059–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bach EA, Aguet M, Schreiber RD. The IFN gamma receptor: a paradigm for cytokine receptor signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997;15:563–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dussurget O, Bierne H, Cossart P. The bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes and the interferon family: type I, type II and type III interferons. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014;4:50. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thapa RJ, et al. NF-kappaB protects cells from gamma interferon-induced RIP1-dependent necroptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:2934–46. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05445-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillon CP, et al. RIPK1 blocks early postnatal lethality mediated by caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell. 2014;157:1189–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thapa RJ, et al. Interferon-induced RIP1/RIP3-mediated necrosis requires PKR and is licensed by FADD and caspases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E3109–E18. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301218110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McComb S, et al. Type-I interferon signaling through ISGF3 complex is required for sustained Rip3 activation and necroptosis in macrophages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E3206–E13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407068111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu Y, et al. Cloning of DLM-1, a novel gene that is up-regulated in activated macrophages, using RNA differential display. Gene. 1999;240:157–63. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00419-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takaoka A, et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 2007;448:501–U14. doi: 10.1038/nature06013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishii KJ, et al. TANK-binding kinase-1 delineates innate and adaptive immune responses to DNA vaccines. Nature. 2008;451:725–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:290–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sridharan H, et al. Murine cytomegalovirus IE3-dependent transcription is required for DAI/ZBP1-mediated necroptosis. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:1429–41. doi: 10.15252/embr.201743947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maelfait J, et al. Sensing of viral and endogenous RNA by ZBP1/DAI induces necroptosis. EMBO J. 2017;36:2529–43. doi: 10.15252/embj.201796476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thapa RJ, et al. DAI senses influenza A virus genomic RNA and activates RIPK3-dependent cell death. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:674–81. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koehler H, et al. Inhibition of DAI-dependent necroptosis by the Z-DNA binding domain of the vaccinia virus innate immune evasion protein, E3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:11506–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700999114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen D, et al. PUMA amplifies necroptosis signaling by activating cytosolic DNA sensors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:3930–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717190115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuriakose T, et al. ZBP1/DAI is an innate sensor of influenza virus triggering the NLRP3 inflammasome and programmed cell death pathways. Sci. Immunol. 2016;1:2. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aag2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton K, et al. RIPK1 inhibits ZBP1-driven necroptosis during development. Nature. 2016;540:129-+. doi: 10.1038/nature20559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin J, et al. RIPK1 counteracts ZBP1-mediated necroptosis to inhibit inflammation. Nature. 2016;540:124±. doi: 10.1038/nature20558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng S, et al. Cleavage of RIP3 inactivates its caspase-independent apoptosis pathway by removal of kinase domain. Cell. Signal. 2007;19:2056–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Y, Devin A, Rodriguez Y, Liu ZG. Cleavage of the death domain kinase RIP by caspase-8 prompts TNF-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2514–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Du F, Wang X. TNF-alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell. 2008;133:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaiser WJ, et al. RIP1 suppresses innate immune necrotic as well as apoptotic cell death during mammalian parturition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:7753–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401857111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rickard JA, et al. RIPK1 regulates RIPK3-MLKL-driven systemic inflammation and emergency hematopoiesis. Cell. 2014;157:1175–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun L, et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell. 2012;148:213–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho YS, et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He S, et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;137:1100–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang DW, et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science. 2009;325:332–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1172308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen W, et al. Diverse sequence determinants control human and mouse receptor interacting protein 3 (RIP3) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) interaction in necroptotic signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:16247–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.435545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang Z, et al. RIP1/RIP3 binding to HSV-1 ICP6 initiates necroptosis to restrict virus propagation in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:229–42. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:290–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rebsamen M, et al. DAI/ZBP1 recruits RIP1 and RIP3 through RIP homotypic interaction motifs to activate NF-kappa B. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:916–22. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Mocarski ES. Receptor-interacting protein homotypic interaction motif-dependent control of NF-kappa B activation via the DNA-dependent activator of IFN regulatory factors. J. Immunol. 2008;181:6427–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu XN, et al. Distinct roles of RIP1-RIP3 hetero- and RIP3-RIP3 homo-interaction in mediating necroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:1709–20. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen X, et al. Translocation of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein to plasma membrane leads to necrotic cell death. Cell Res. 2014;24:105–21. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelliher MA, et al. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal. Immunity. 1998;8:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ting AT, Pimentel-Muinos FX, Seed B. RIP mediates tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 activation of NF-kappaB but not Fas/APO-1-initiated apoptosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:6189–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duprez L, et al. RIP kinase-dependent necrosis drives lethal systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Immunity. 2011;35:908–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tracey KJ, et al. Shock and tissue injury induced by recombinant human cachectin. Science. 1986;234:470–4. doi: 10.1126/science.3764421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huys L, et al. Type I interferon drives tumor necrosis factor-induced lethal shock. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:1873–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vanlangenakker N, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. Many stimuli pull the necrotic trigger, an overview. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:75–86. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pasparakis M, Vandenabeele P. Necroptosis and its role in inflammation. Nature. 2015;517:311–20. doi: 10.1038/nature14191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berger SB, et al. Cutting edge: RIP1 kinase activity is dispensable for normal development but is a key regulator of inflammation in SHARPIN-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 2014;192:5476–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Polykratis A, et al. Cutting edge: RIPK1 kinase inactive mice are viable and protected from TNF-induced necroptosis in vivo. J. Immunol. 2014;193:1539–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dannappel M, et al. RIPK1 maintains epithelial homeostasis by inhibiting apoptosis and necroptosis. Nature. 2014;513:90±. doi: 10.1038/nature13608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi N, et al. RIPK1 ensures intestinal homeostasis by protecting the epithelium against apoptosis. Nature. 2014;513:95–9. doi: 10.1038/nature13706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ofengeim D, et al. Activation of necroptosis in multiple sclerosis. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1836–49. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:11929–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen WZ, et al. Ppm1b negatively regulates necroptosis through dephosphorylating Rip3. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:434±. doi: 10.1038/ncb3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen WZ, et al. Diverse sequence determinants control human and mouse receptor interacting protein 3 (RIP3) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) interaction in necroptotic signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:16247–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.435545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ZBP1 mediates interferon-induced necroptosis-supplementary