Abstract

Introduction and Hypothesis

Urethral mucosal prolapse is most frequently seen in children and postmenopausal women, and extremely rare in young adult patients. In this context, we aim to describe our experience with this condition and compare our findings with the literature.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of our outpatient micturition disorders clinic (between August 2014 and April 2017) for patients with a diagnosis of urethral mucosal prolapse, seeking to evaluate their demographic characteristics, presenting complaints, treatment, and outcomes.

Results

We found 12 cases of urethral mucosal prolapse, including a mother and daughter and a reproductive-aged patient. Presenting symptoms included bleeding, urinary retention, partially thrombosed mucosa, and pain. Misdiagnosis was common and caused treatment delay, even in some very symptomatic patients.

Conclusion

Urethral mucosal prolapse is a readily diagnosed condition and often associated with complications in our series. Proper diagnosis is key to successful, timely treatment. Descriptive studies such as this are important to raise awareness of this diagnosis and improve patient care.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13224-019-01288-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Prolapse treatment, Urethral caruncle, Urethral mass, Urethral prolapse, Urological surgery, Vaginal bleeding

Introduction

Urethral prolapse (UP) is a circular eversion of the urethral mucosa through the urethral meatus in women. It was first described in 1732 by Solinger and is an uncommon condition that affects mainly black prepubertal girls and postmenopausal women [1]. As the majority of UPs occur in the pediatric age group [2], there are few reports in adults. Diagnosis is essentially clinical, by observation of a doughnut-shaped mass protruding from the urethra. As an uncommon condition, UP is often misdiagnosed initially, sometimes even in the pediatric population [3]. Descriptive studies of its occurrence in the adult population are thus warranted in order to draw attention for this simple, readily diagnosed condition. UP is usually asymptomatic, especially in children; when manifestations are present, blood in the underwear is the most common chief complaint. Treatment may be surgical or conservative, although this is a point of contention [4]. There are no large series and no studies comparing different treatment approaches in adulthood. Etiology is also unclear; one of the proposed hypotheses is estrogen deficiency, which would justify the bimodal age distribution [1, 2, 5–7]. Our aim is to discuss this condition and report our experience with 12 adult patients, including one case in a woman of childbearing age, a population group in which this condition is extremely rare [2, 5].

Patients and Methods

After ethics committee approval, we reviewed the medical records of all cases diagnosed as urethral mucosal prolapse and treated at our outpatient micturition disorders clinic between August 2014 and April 2017. Age, skin color, body mass index (BMI), reason for referral, symptoms, risk factors that may contribute to the development of UP, diagnosis made at our department, treatment, outcome, and additional relevant information were obtained from medical records. For those patients whose cases were documented photographically, relevant images were included in this publication after obtaining specific written consent.

Results

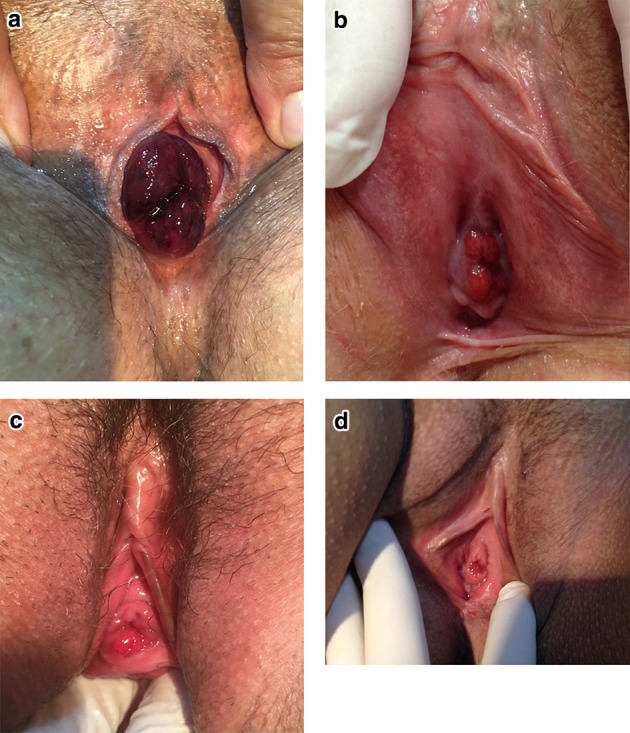

A review of records of our outpatient adult micturition disorders clinic yielded 12 cases of UP, all treated successfully. These included one case of a small but highly symptomatic urethral mucosal prolapse in a 21-year-old patient (case 6, Fig. 1), which was successfully treated with topical estrogen [2, 8, 9]; a mother and daughter who presented simultaneously, both with UP; and several cases with complications, including urinary retention, bleeding, and thrombosis of the prolapsed urethral mucosa (Table 1). Correct diagnosis was rarely established before referral to our clinic (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

a Case number 12, b case number 6: reproductive-aged patient with a small urethral mucosal prolapse, c, d highly symptomatic small partial urethral mucosal eversion in two reproductive-aged patients

Table 1.

Description of the cases, treatment, and outcomes

| Age | Skin color | BMI | Reason for referral | Symptoms | Risk factors | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 56 | White | 27 | Urethral neoplasm | Pain, bleeding, and incontinence for 1 year | Postmenopausal | Bleeding and painful urethral prolapse | Surgical excision and sling | Success |

| 2 | 57 | Black | 23 | Urethral mass | Bleeding and incontinence for 8 months | Postmenopausal | Bleeding urethral prolapse | Surgical excision and sling | Success. Treated for urethral caruncle with topical creams. |

| 3 | 78 | White | 19 | Presented to emergency department | Pain and urinary retention | Postmenopausal | Partial thrombosis of a large urethral prolapse | Surgical excision | Success |

| 4 | 86 | White | 29 | Urethral caruncle | Vulvar mass and pain for 20 days | Postmenopausal | Uncomplicated total prolapse | Surgical excision | Success. Before referral, patient had been treated for more than a year for urethral caruncle. |

| 5 | 62 | White | 31 | Urethral prolapse | Vulvar mass and mild pain of acute onset | Postmenopausal, excessive walking | Uncomplicated total prolapse | Surgery | Success. This patient is the daughter of patient number 4. |

| 6 | 21 | White | 20 | Vaginal bleeding | Bleeding and mild pain | Contraceptive drugs for 4 years | Bleeding urethral prolapse | Medical, for 6 weeks | Success |

| 7 | 65 | White | 24 | Urethral tumor | Dyspareunia and vulvar mass | Postmenopausal | Uncomplicated prolapse | Medical, for 12 weeks | Prolapse resolved, but persistent dyspareunia |

| 8 | 69 | White | 24 | Postoperative vulvar pain | Asymptomatic | 14th postoperative day of vaginal prolapse | Uncomplicated prolapse | Medical for 6 months than surgery | Success |

| 9 | 55 | White | 23 | Urethral prolapse | Urethral pain | Postmenopausal | Painful urethral prolapse | Surgical excision | Success |

| 10 | 64 | White | 27 | Urethral neoplasm | Vulvar mass and bleeding in the last month | Postmenopausal | Bleeding urethral prolapse | Surgery | Success. Treated for more than a year for urethral caruncle |

| 11 | 69 | White | 26 | Pelvic prolapse | Pain and acute vulvar mass | Postmenopausal and Pilates exercises | Painful urethral prolapse | Reduction followed by surgery | Success initially, but developed a urethral caruncle 3 years later. |

| 12 | 73 | white | 28 | Presented to emergency room with vaginal bleeding | Pain, bleeding, and vulval mass | Postmenopausal | Bleeding urethral prolapse and vascular thrombosis | Surgery | Success |

Discussion

Urethral prolapse occurs when the distal urethral mucosa protrudes through the external meatus. The diagnosis is based essentially on by clinical findings on physical examination, which reveals an anterior vulvar bulk of soft, friable tissue, with the urethral meatus usually in the center (a “doughnut”-shaped mass). In symptomatic cases, vaginal bleeding is the most common complaint; however, hematuria, dysuria, frequency, urgency, nocturia, pain, dyspareunia, and urinary retention are other potential presenting symptoms. Imaging is usually unnecessary and should be ordered only if another condition or infection is suspected [2]. All cases in our series were promptly recognized by our staff as urethral mucosal prolapse, despite very different presentations, including trips to the emergency room with acute complications or during routine appointments in the clinic.

UP is an uncommon condition, occurring more frequently in prepubertal girls and postmenopausal women; the possibility should always be considered when evaluating a periurethral lesion in these patients. The differential diagnosis includes neoplasm (vaginal rhabdomyosarcoma, urethral carcinoma or papilloma); urethral caruncle, polyp, or diverticulum; Skene’s cyst; abscess; HPV; prolapsing ureterocele; imperforate hymen; and sexual abuse [10].

In our cases, three patients were treated for more than a year on the basis of an incorrect diagnosis of urethral caruncle, without resolution. One can argue that the conservative treatment with topic estrogen is the same for both conditions, but resolution was nevertheless considerably delayed in the presence of major symptoms.

The pathophysiology of UP remains uncertain. The main etiologic hypothesis is estrogen deficiency, because of the preponderance of UP in the prepubertal and postmenopausal periods. Postpartum, there is a mild estrogen deficiency, which may explain the rare cases that occur in this period [9]. Other contributing factors include high intra-abdominal pressure, perineal or urethral trauma (including catheterization), injection of bulking agents, sexual abuse, and infection [7]. One case in our series occurred in the early postoperative period (case 8), consistent with surgical pelvic trauma or pelvic prolapse reduction provoking urethral prolapse. Two cases (patients 5 and 11) were consistent with acute elevation of intra-abdominal pressure, both presenting with acute onset (or new perception) of vaginal mass. As expected, all but one of our cases were postmenopausal.

In 1986, Lowe studied the histopathology of UP and observed a cleavage plane between the inner longitudinal and outer circular-oblique smooth muscle layers of the urethra, as well as marked mucosal eversion and vascular congestion [6, 10]. Another possible risk factor could be a malformation or weak collagen structures, since many patients report a family history of hernias and vaginal prolapses. In our series, we observed this association in two of our cases—a mother and daughter who presented with UP simultaneously. However, additional research of larger samples is needed to study the role of familiar inheritance.

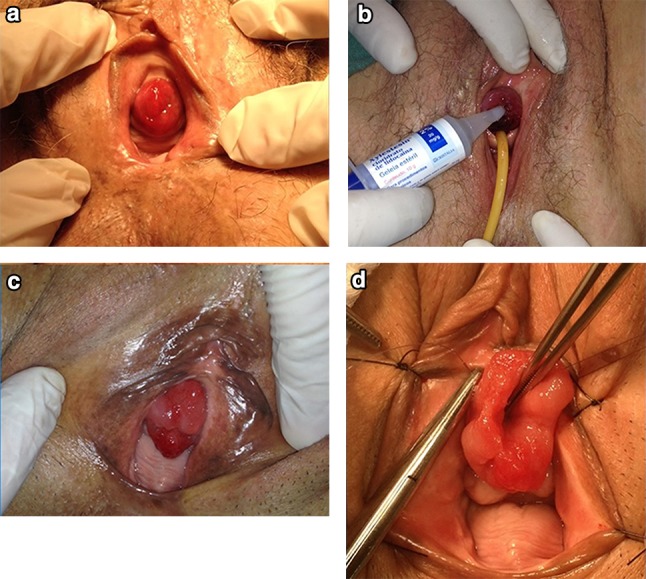

UP can be complicated or uncomplicated and partial or total. It is complicated when there is vascular thrombosis of the mucosa, significant bleeding, pain, infection, or urinary retention. Almost all of these complications were represented in our series, as described in Table 1 and illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2, suggesting that these complications are not uncommon and that prompt recognition and treatment of UP are important to prevent them. Otherwise, the most common presentation is uncomplicated prolapse, which can be fully asymptomatic or present with minor bleeding or mild pain. The theory is that UP begins as a partial prolapse and becomes complete (circumferential), since in many cases a complete prolapse becomes partial with conservative measures and an untreated partial prolapse can become complete. There were some cases in our clinic of minor partial extrusion of the urethral mucosa through the meatus (Fig. 1), causing discomfort; these occurred in patients of childbearing age and were successfully treated with topical estrogen. This clinical picture has rarely been described in the literature, but in our clinic it was rather common and very symptomatic.

Fig. 2.

a Case number 1, b case number 3, c case number 10, d case number 9 at the start of surgery

Treatment of UP is controversial and can be surgical or conservative. The nonsurgical approach consists basically of sitz bath and topical estrogen cream for approximately 6 weeks; we usually recommend it for mild or asymptomatic cases [8, 10, 11]. As urinary infection is rare, antibiotics are unnecessary. Topical steroids are ineffective. The success of nonsurgical treatment is variable, ranging from 33 to 92%, and appears to be more effective in prepubertal girls than in postmenopausal women [10]. In some cases, spontaneous resolution may occur. The recurrence rate with conservative management is up to 67%, while surgery is associated with higher cure rates and rapid relief of symptoms [5].

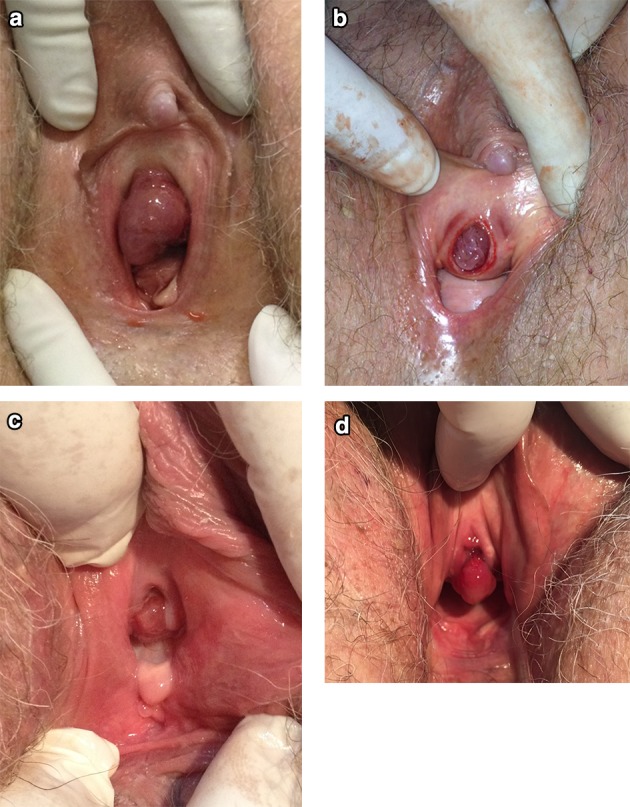

In our series, all postmenopausal patients were treated surgically with good outcomes. There are many surgical options, all of which include resection of the prolapsed mucosa (over a Foley catheter or not) and suture of the urethral mucosa to the meatus. We used the modified Kelly–Burnham (or four-quadrant excisional) technique, which involves placing four stitches in four quadrants of prolapsed mucosa, incising each quadrant between the holding sutures up to the mucocutaneous junction, without a Foley catheter, followed by immediate approximation of the mucocutaneous junction with absorbable sutures [7, 10]. Another option is manual prolapse reduction under general anesthetic, but this is associated with a risk of only partial reduction of 62% and recurrence of 12% in children. This technique has not been studied in adults [12]. In one case in our series, we performed manual reduction in the emergency room, but recurrence occurred after only a few hours; hence, we decided to perform surgery (Fig. 3). Some authors argue that slings can be effective to treat UP [13]. We have used slings in combination with UP excision with good results, but only in cases where there was comorbid stress urinary incontinence; additional research is needed to study the impact of this approach in other situations.

Fig. 3.

All images are from case 11. a Before surgery, b prolapse reduced in the emergency room, c two-month postoperative follow-up after topical estrogen replacement, d three years after surgery, a urethral caruncle developed

Therefore, we believe that management should be individualized, with the conservative approach selected for asymptomatic or mild cases and surgical excision for complicated or very symptomatic patients.

In short, UP is an underdiagnosed entity not only due to its rarity, but also to the unfamiliarity of clinicians—even specialists—with this condition. Complications are not uncommon, and although UP should be readily recognized by clinical examination alone, correct diagnosis is the main determining factor of timely treatment and resolution of symptoms. We hope this descriptive study can raise awareness of this diagnosis in the adult population and improve the care of these patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Alexandre Fornari

(MD, MSC. Urologist) Head of Mictional Dysfunction Unit and Urology residency preceptor of Santa Casa Hospital, Urology Department, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Professor of the graduating course in Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation at Inspirar Faculty. Head of the Brazilian Urological Society—Rio Grande do Sul 2018–19. ICS Urodynamics Committee member 2017–2022.

Author Contributions

AF: Data collection, management, data analysis, and manuscript writing and editing. MG: Data collection, management. JCLM: Data collection, Management, manuscript writing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the article.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors Alexandre Fornari, Marina Gressler, and Jean Carlos Levay Murari declare that they have no conflict of interest to declare about this study. They did not work or receive any benefit that can be linked with this study by the industry or other sponsor in the last five years. The study was supported by the authors.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. It was carried out at the Outpatient Micturition Disorders Clinic, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre; Urology Department, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Address: Prof. Annes Dias St, 135. Porto Alegre, Brazil. Zip code 90020-170. Phone + 55 51 3214 8000.

Ethics Committee Approval

This study was approved by the Santa Casa de Porto Alegre ethics committee number CAEE 15106913.0.00005335. According to the ethics committee, there is no need of informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study, based only in medical records. All pictures received written consent to be published, kept by the corresponding author, and available if necessary. The ethical committee permission letter is available as PDF file in the supplementary material.

Footnotes

Alexandre Fornari is a urologist and head of Outpatient Micturition Disorders Clinic, Urology Department, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Marina Gressler is a staff urologist in Outpatient Micturition Disorders Clinic, Urology Department, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Jean Carlos Levay Murari is a staff urologist in Outpatient Micturition Disorders Clinic, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, and in Urology Department, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wei Y, Wu SD, Lin T, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of urethral prolapse in children: 16 years’ experience with 89 Chinese girls. Arab J Urol. 2017;15(3):248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jessop ML, Zaslau S, Al-Omar O. A case of strangulated urethral prolapse in a premenopausal adult female. Case Rep Urol. 2016;2016:1802623. doi: 10.1155/2016/1802623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arzubi-Hughes MK, Salts LA, et al. Diagnosing and managing common genital emergencies in pediatric girls. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2018;15(10):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall ME, Oyesanya T, Cameron AP. Results of surgical excision of urethral prolapse in symptomatic patients. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(8):2049–2055. doi: 10.1002/nau.23232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olumide A, Kayode Olusegun A, Babatola B. Urethral mucosa prolapse in an 18-year-old adolescent. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:231709. doi: 10.1155/2013/231709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ninomiya T, Koga H. Clinical characteristics of urethral prolapse in Japanese children. Pediatr Int. 2017;59(5):578–582. doi: 10.1111/ped.13226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holbrook C, Misra D. Surgical management of urethral prolapse in girls: 13 years’ experience. BJU Int. 2012;110(1):132–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorado M, Molina R, Álvarez M, et al. Urethral prolapse, is surgical treatment necessary? Arch Esp Urol. 2019;72(6):619–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreiner L, Nygaard CC, Anschau F. Urethral prolapse in premenopausal, healthy adult woman. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(2):353–354. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1820-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill AJ, Siff L, Vasavada SP, et al. Surgical excision of urethral prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(10):1601–1603. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiogbe MA, Hounnou GM, Koura A, et al. Urethral mucosal prolapse in young girls: a report of nine cases in Cotonou. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2011;8(1):12–14. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.78661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballouhey Q, Abbo O, Sanson S, et al. Urogenital bleeding revealing urethral prolapse in a prepubertal girl. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2013;41(6):404–406. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin P, Harvie HS, Guerette NL. Novel approach for correction of urethral prolapse using a retropubic sling with urethral fixation. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(8):995–997. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0806-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.