Introduction

Hypereosinophilic syndromes are rare disorders defined by persistent peripheral eosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count >1.5 × 109/L) plus evidence of organ involvement.1 They are subclassified into primary or myeloid hypereosinophilic syndromes, secondary or lymphocytic hypereosinophilic syndromes, and idiopathic. Secondary or lymphocytic hypereosinophilic syndrome is thought to be due to a T-cell population secreting interleukin (IL) 5.1 Treatment is based on subtype, organ(s) involved, and the presence of genetic targets.1 First-line therapy for the idiopathic and secondary or lymphocytic hypereosinophilic syndrome variants is systemic steroids. Steroid-sparing options are somewhat limited and not always effective.2 We present a patient with recalcitrant idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome manifesting as an intensely pruritic eczematous dermatitis who experienced a rapid and remarkable symptomatic response to dupilumab treatment in the setting of concurrent hydroxyurea therapy.

Case report

A 57-year-old man presented with a 6-month history of worsening pruritic dermatitis, which failed to respond to topical or systemic steroids. Medical history was notable for morbid obesity and adult-onset diabetes controlled with metformin. The patient's baseline medications were started more than 1 year before the onset of his condition, and no family members were similarly affected. Physical examination revealed diffuse lichenified and excoriated papulonodules, some coalescing into plaques, which spared palms and soles (Fig 1, A).

Fig 1.

Clinical improvement within 3 weeks after dupilumab treatment. A, Widespread, hyperpigmented papulonodules were present diffusely across the head and neck region, resembling papular eczema. B, Marked improvement in papulation was observed after 3 weeks of treatment with dupilumab.

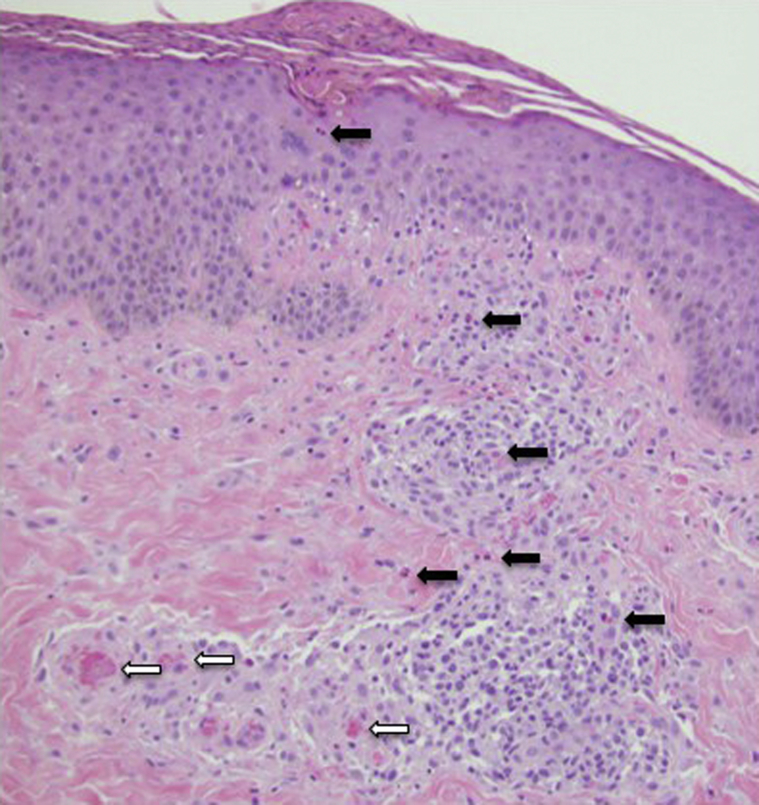

Skin biopsy showed spongiosis with intraepidermal eosinophils and dermal perivascular inflammation with numerous eosinophils (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with evidence of scratching and overlying parakeratotic scale. There was a wedge-shaped infiltrate of lymphocytes with numerous eosinophils (black arrows) and associated microthrombi (white arrows) in superficial vessels. (Original magnification: ×100.)

Laboratory studies, including complete blood cell count with differential, metabolic panel, vitamin B12, lactate dehydrogenase, total immunoglobulin E, total tryptase, immunoglobulin E specific for Dermatophagoides mites, and stool for ova and parasites, had results significant only for an absolute eosinophil count of 1.9 × 109/L (normal <0.5 × 109/L), lactate dehydrogenase level of 422 U/L (normal 118-225 U/L), and total immunoglobulin E level of 859 kU/L (normal 0-158 kU/L). Fluorescence in situ hybridization result for platelet-derived growth factor receptor-FIP1-like-1 fusion protein was negative. Bone marrow aspirate revealed 15% eosinophils with normal hematopoiesis. T-cell receptor-γ gene rearrangement studies identified a clonal population. Overproduction of IL-5 was not identified. A chest computed tomographic scan result was negative for significant lymphadenopathy but revealed patchy, panlobular, ground-glass opacities. Pulmonary function test results were normal and autoimmune serology results were negative or normal.

Initial management included narrowband phototherapy, mid- to high-potency topical steroids, gabapentin 900 mg twice daily, and hydroxyzine 25 mg 3 times daily. These therapies were minimally effective and the patient's absolute eosinophil count remained elevated, reaching levels as high as 2.3 × 109/L (Fig 3). Systemic steroids were minimally effective and caused significant hyperglycemia.

Fig 3.

Clinical course as a function of absolute eosinophil count, systemic treatments, and disease severity. In the interest of space and clarity, previous dose of prednisone and absolute eosinophil counts are not included in figure. AEC, Absolute eosinophil count.

Pegylated interferon α-2α 180 μg/week was initiated (Pegasys, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA), which reduced the patient's absolute eosinophil count to less than 0.3 × 109/L within 2 weeks, but did not improve pruritus. Interferon-α was discontinued because of periorbital edema and lack of efficacy. The patient began receiving mepolizumab, a humanized anti–IL-5 antibody (300 mg subcutaneously/month), which reduced his absolute eosinophil count to less than 0.2 × 109/L but failed to improve symptoms even after 9 injections. Trials of other anti–IL-5 and –IL-5R biologics (reslizumab and benralizumab, respectively) were considered. Because intractable pruritus was the primary symptom that adversely affected his quality of life, he began receiving dupilumab. While obtaining prior authorization, the patient began receiving hydroxyurea, with his dose titrated up to 2,000 mg/day.

Four weeks after initiation of dupilumab therapy (600-mg loading dose followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks), his papules, nodules, and plaques began to flatten (Fig 1, B). He reported remarkable reduction in pruritus and was able to reduce both his doses of hydroxyurea to 1,000 mg/day and his anti-itch therapies (gabapentin 300 mg/day and hydroxyzine 25 mg/day). His disease severity score decreased from 10 of 10 to 3 of 10 (Fig 3). Repeated chest computed tomography 23 weeks after initiation of dupilumab showed stable opacities and a slight reduction in mediastinal lymph node size from baseline.

Discussion

Greater than 80% of patients with hypereosinophilic syndromes have cutaneous lesions.3 The patchy ground-glass opacities in the lungs observed by computed tomography in our patient are occasionally observed in hypereosinophilic syndromes and may be asymptomatic, as was the case in our patient.3 First-line therapy for hypereosinophilic syndromes is systemic steroids, followed by interferon-α or hydroxyurea as steroid-sparing options, and mepolizumab if these therapies fail.2 Our patient failed treatment or experienced intolerable adverse effects with several of these treatments. Diagnosis of hypereosinophilic syndrome variants such as secondary or lymphocytic hypereosinophilic syndromes can be confounded by concurrent therapies such as prednisone; IL-5 level was tested while our patient was receiving systemic steroids and repeated while he received dupilumab, with negative results (ie, IL-5 was negative or undetectable); thus, we thought that his disease best fit idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, given the lack of full support for secondary or lymphocytic hypereosinophilic syndromes despite extensive evaluation, including multiple cytogenetic studies. Although we believed that much of this patient's symptomatic improvement could be attributed to the initiation of dupilumab, we cannot rule out that its addition to hydroxyurea therapy might have contributed.

Dupilumab inhibits signaling of IL-4 and IL-13, which are elevated in some patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome.4 Recent evidence suggests that IL-4Rα activation enhances the responsiveness of sensory neurons to a number of different pruritogens, and this may be the mechanism by which dupilumab reduces itch.5 For these reasons, we speculated that dupilumab might be an effective symptomatic treatment for our patient. Dupilumab is Food and Drug Administration approved to treat atopic dermatitis, asthma, and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis.6 In accordance with the remarkable efficacy of dupilumab in alleviating the pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis, as well as its favorable safety profile,7 we tested its efficacy to decrease our patient's recalcitrant pruritus. To our knowledge, this is the first published report demonstrating the benefit of dupilumab in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Dupilumab is an effective treatment for several conditions characterized by elevated or activated eosinophils, including asthma, atopic dermatitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis.7 It may be important to monitor absolute eosinophil count in patients with hypereosinophilic syndromes treated with dupilumab because this drug has been associated with transient increases in patients with asthma and atopic dermatitis.8,9 In the SOLO 1 and 2 atopic dermatitis phase 3 trials, less than 1% of patients developed severe absolute eosinophil count levels (>5.0 × 109/L); this was typically observed approximately 4 to 8 weeks into treatment, and by 12 weeks no patients continued to have counts in the severe range.9 A greater percentage (8.4%-9.7%) of dupilumab-treated patients developed moderate absolute eosinophil counts (1.5-5.0 × 109/L) compared with placebo-treated patients (3.1%-6.4%), but with no adverse events associated with these levels. This transient increase in absolute eosinophil count may be due to reduced tissue migration of eosinophils, possibly by blocking the expression of vascular cell adhesion protein-1, which selectively adheres to eosinophils.10 At 16 weeks into dupilumab treatment, our patient's absolute eosinophil count had increased to 0.3 × 109/L, which is still within normal limits. The concomitant treatment with hydroxyurea may explain why only a modest increase in absolute eosinophil count was observed.

In summary, initiation of dupilumab in the setting of concurrent hydroxyurea therapy was markedly effective and well tolerated in our treatment-recalcitrant patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome. In accordance with this case and data supporting a role for T-helper 2 cell cytokines (particularly in secondary or lymphocytic hypereosinophilic syndromes), we believe a proof-of-concept trial to better establish safety and efficacy of dupilumab (with or without concurrent hydroxyurea) in hypereosinophilic syndromes is warranted.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: Dr Wieser is a subinvestigator in clinical trials with dupilumab for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (Regeneron). Dr Prezzano was a subinvestigator in clinical trials with dupilumab for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (Regeneron). Dr Beck is the principal investigator in clinical trials with dupilumab for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (Regeneron). Drs Kuehn, Cusick, Stiegler, Scott, and Liesveld have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Simon H.U., Rothenberg M.E., Bochner B.S. Refining the definition of hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuang F.L., Klion A.D. Biologic agents for the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1502–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefèvre G., Copin M.C., Staumont-Sallé D. The lymphoid variant of hypereosinophilic syndrome: study of 21 patients with CD3-CD4+ aberrant T-cell phenotype. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93(17):255–266. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roufosse F., Schandené L., Sibille C. Clonal Th2 lymphocytes in patients with the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2000;109(3):540–548. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oetjen L.K., Mack M.R., Feng J. Sensory neurons co-opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell. 2017;171(1):217–228.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck L.A., Thaçi D., Hamilton J.D. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):130–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deleuran M., Thaçi D., Beck L.A. Dupilumab shows long-term safety and efficacy in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis patients enrolled in a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro M., Corren J., Pavord I.D. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in moderate-to-severe uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2486–2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollenberg A., Beck L.A., Blauvelt A. Laboratory safety of dupilumab in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from three phase III trials (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1, LIBERTY AD SOLO 2, LIBERTY AD CHRONOS) Br J Dermatol. 2019 doi: 10.1111/bjd.18434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bochner B.S., Klunk D.A., Sterbinsky S.A., Coffman R.L., Schleimer R.P. IL-13 selectively induces vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in human endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1995;154(2):799–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]