Abstract

Xia-Gibbs syndrome (XGS) is a rare neurological disorder characterized by global developmental delay, hypotonia, intellectual disability, seizures, and sleep apnea. XGS is defined by monoallelic pathogenic variants in AHDC1. In this study, we identified a Brazilian patient carrying a likely de novo AHDC1 nonsense mutation (c.451C>T; p.Arg151*) which was absent in both parents. All disease-causative variants already associated with XGS have been reviewed and the mutation described here corresponds to the closest one to the N-terminal region. Our findings were discussed based on the suggested genotype-phenotype correlation of the disease.

Keywords: Exome sequencing, Intellectual disability, Neurodevelopmental disorders, Novel mutation, Sanger sequencing

Established Facts

Pathogenic variants in the AHDC1 gene are related to Xia-Gibbs syndrome, a neurological disorder characterized by global developmental delay, hypotonia, intellectual disability, seizures, and sleep apnea.

Only a few cases have been described worldwide. A possible genotype-phenotype relationship has been suggested between the location of the mutations in AHDC1 and the severity of clinical symptoms.

Novel Insights

We described a new causative variant in AHDC1 in a Brazilian patient. This variant is the closest one to the N-terminal region reported so far.

In 2014, Xia et al. described 4 unrelated patients who presented with language delay, hypotonia, sleep apnea, and mild dysmorphic facial features. All of them were carriers of de novo monoallelic mutations in AHDC1 (AT-hook DNA-binding motif-containing 1; RefSeq accession number NM_001029882.2). At that time, it was suggested that the patients presented a new genetic syndrome defined by mutations in AHDC1, which now is currently known as Xia-Gibbs syndrome (XGS; OMIM 615829). In addition to the main clinical characteristics primarily reported, patients with XGS may also have behavioral disturbances, seizures, and other features [Jiang et al., 2018; Ritter et al., 2018].

The prevalence of XGS is unknown, but since the first reports, approximately 100 cases have been described in the literature [Xia et al., 2014; Quintero-Rivera et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015; Bosch et al., 2016; García-Acero and Acosta, 2017; Miller et al., 2017; Park et al., 2017; Popp et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2018; Ritter et al., 2018; Díaz-Ordoñez et al., 2019; Murdock et al., 2019]. New cases were identified mainly through whole-exome sequencing (WES), since XGS clinical presentation is heterogeneous and nonspecific [Jiang et al., 2018].

Here, we describe a novel nonsense variant in the AHDC1 gene in a Brazilian case of XGS, along with a detailed clinical description of the proband, contributing to the genotype-phenotype correlation of the disease.

Case Report

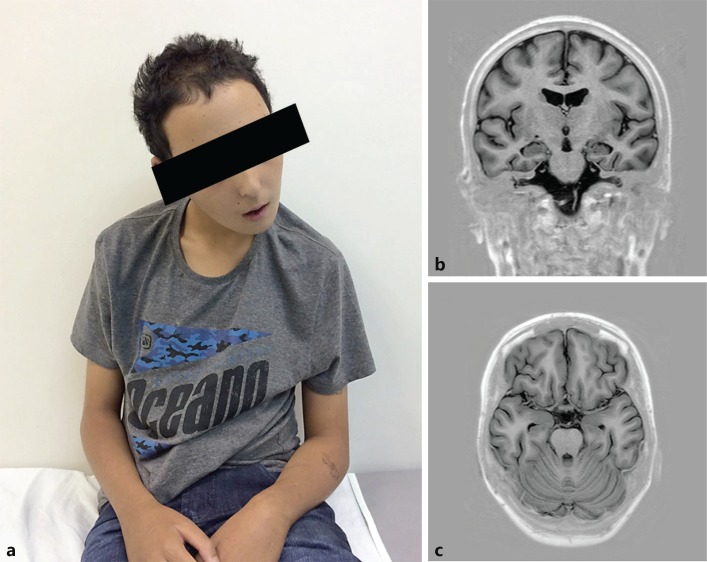

A Brazilian male patient (Fig. 1a), was referred to a medical geneticist at 8 years of age to investigate intellectual disability, seizures, and behavior disorder. Pregnancy history was remarkable for preterm contractions. He was born at late preterm (35 weeks) to unrelated parents, with a weight of 2,750 g (75th percentile), height 46 cm (50th percentile), and an Apgar score 9/10. He remained in observation during his first hours of life due to tachypnea but evolved to brief hospital discharge without other complications. No other medical issues in the first months of life were registered. He attained motor and speech milestones during his first 2 years. Seizures started at 21 months of age, with partial loss of motor skills, and recovered by 30 months of age. Speech was seriously affected, with loss of sentences. By school age, he presented severe learning disability. At later infancy, serious behavior disorder, including difficulties in social interaction, aggression episodes, and suicide attempt were reported.

Fig. 1.

a-c Patient at 15 years of age, showing minimum dysmorphic features, including a broad forehead and thin upper lip (a). Brain MRI showing mild diffuse brain atrophy on coronal (b) and axial (c) T1-weighted inversion recovery.

At the time of his first evaluation (8 years of age), the seizures and behavior disorder were partially controlled with valproic acid and haloperidol. At physical examination, he presented normal growth and head circumference, with minor dysmorphic features, including widow's peak, broad forehead, synophrys, and a melanocytic nevus on left thigh. Karyotyping, genetic testing for Fragile X syndrome, and neuroimaging had normal results, and the clinical features were assigned to multifactorial etiology. The patient then returned at 13 years of age, after worsening of epilepsy and behavior disorder. He also presented with dysphagia, scoliosis, movement disorder (bradykinesia, myoclonic tremor, and cerebellar signs), and sleep apnea. He was on psychiatric follow-up, with schizophrenia diagnosis. Neuroimaging detected mild cerebral atrophy (Fig. 1b, c). The patient was receiving 3 antiepileptic and 3 antipsychotic drugs, with poorly controlled aggressive behavior. During 1 month of psychiatric internment at 17 years of age, he was submitted to a pharmacological washout with improvement of the psychiatric symptoms.

Molecular Analysis

Patient blood sample was sent to CENTOGENE for WES as diagnostic workup. Singleton-based (index case) WES was performed as described previously [Trujillano et al., 2017a]. In short, the Nextera Rapid Capture Exome Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) or the SureSelect Human All Exon Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) were used for enrichment, and a HiSeq4000 (Illumina) instrument for the actual sequencing (average coverage was targeted to 100×). Variants calling, annotation, and prioritization were based on a set of publicly available and in-house tools [Trujillano et al., 2017a].

Selection of the variants for reporting was done taking into account the compatibility with the suspected phenotype and suspected disease mechanism. All provided clinical data, family history, disease onset/course, available test results, and clinical suspicion were considered. All modes of inheritance and all relevant variant information were evaluated: zygosity, nature of the variant, and the frequency in public databases (gnomAD, ExAc, and disease-centered databases - HGMD [Stenson et al., 2003] and CentoMD® [Trujillano et al., 2017b]). Variant nomenclature followed standard recommendations [den Dunnen et al., 2016].

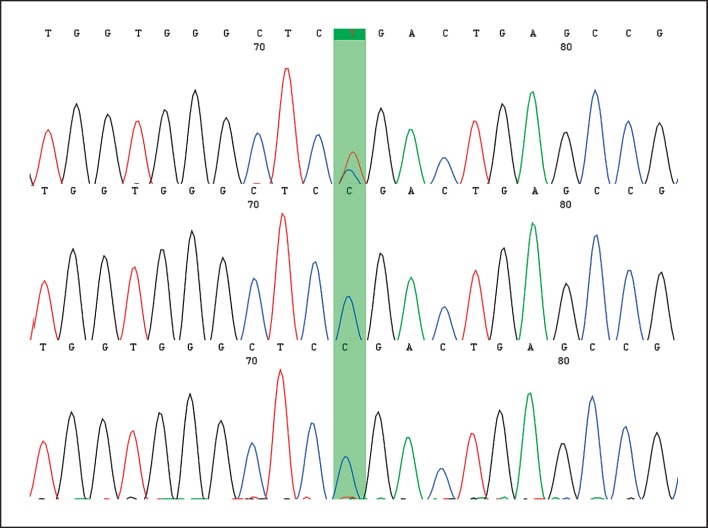

The best candidate variant was detected in AHDC1, heterozygous NM_001029882.3:c.451C>T; p.(Arg151*). The variant leads to a premature protein termination, similar to other reported variants in XGS, and it is not reported in any database, including CentoMD. Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of the variant in the proband and its absence in both maternal and paternal DNA (Fig. 2), in line with a de novo origin. The variant was classified as pathogenic according to the ACMG guidelines [Richards et al., 2015]. The AHDC1 variant has been deposited in the LOVD 3.0 database (https://www.lovd.nl/) under the accession number #0000478183.

Fig. 2.

The upper chromatogram represents the result of the son affected by Xia-Gibbs syndrome, showing the presence of the c.451C> T mutation in AHDC1. The other chromatograms represent those of both parents, emphasizing only the presence of the wild allele.

Discussion and Conclusion

Since the first report of XGS in 2014, approximately a hundred cases have been identified around the world, with only 2 in Latin America, in 2 Colombian girls [García-Acero and Acosta, 2017; Díaz-Ordoñez et al., 2019]. This is the first case reported in Brazil. The index case is also one of the oldest patients in the literature, with the majority of the cases being children under 10 years of age.

The classical findings of XGS were found in the proband, such as neuropsychomotor developmental delay, seizures, and mild dysmorphic facial features [Jiang et al., 2018]. The patient also showed less common clinical features such as aggressive behavior, scoliosis, and movement disorders. Psychiatric disturbances, which seemed alarming in this case, were reported in a few cases. Murdock et al. [2019] reported the oldest case to date, a 55-year-old male, with impulsive aggressive behavior and self-harm episodes since childhood. Sleep apnea, described in many patients, was clinically observed in our patient after puberty, however, without polysomnographic confirmation. Although hetero aggressive behavior is uncommon, self-injury was reported by several parents of children with XGS [Jiang et al., 2018]. Movement disorders in our patient included ataxia, which may be encountered in up to 65% of the patients with XGS [Jiang et al., 2018], bradykinesia, and myoclonic tremor. It is not known if the latter 2 findings, which were not previously reported, are part of the XGS spectrum of manifestations, and a more comprehensive analysis of the movement disorders in this condition is warranted.

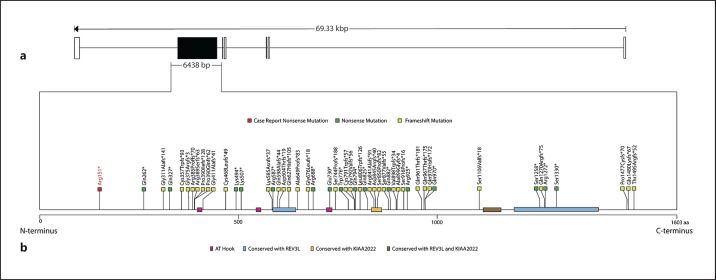

The nonsense variant in AHDC1 reported here (c.451C>T; p.Arg151*) is a novel mutation and the closest one to the N-terminal region ever described (Fig. 3; Table 1). This is particularly interesting because a genotype-phenotype correlation between mutations in AHDC1 and XGS has been suggested [Jiang et al., 2018] with variants close to the C-terminus having more severe clinical outcomes, while mutations close to the N-terminus were linked to milder features. However, the patient presented here was severely affected, particularly with psychiatric disturbances. This is similar to the case presented by Murdock et al. [2019]: a patient with severe intellectual disability carrying a frameshift mutation located in the beginning of the AHDC1 gene (p.Gln327*). In turn, another case reported was of a patient with only moderate intellectual disability, speaking 3 different languages and carrying a mutation very close to the C-terminal region (p.Cys1499Valfs*9) [Ritter et al., 2018].

Fig. 3.

Graphic representation of the AHDC1 gene and its 7 exons (rectangles). a The only coding exon (exon 6) is represented by a black rectangle (scale: 1 pixel = 50 bp). b Graphic description of the AHDC1 protein and its main domains represented by colored rectangles: pink, AT-Hook; blue, REV3L homology; orange KIAA2022 homology; brown, both REV3L and KIAA2022 homology. All known mutations, according to Murdock et al. [2019], Ritter et al. [2018], García-Acero and Acosta [2017], and Díaz-Ordoñez et al. [2019], are represented by colored squares: dark green, nonsense mutation; light green, frameshift mutation. The red square represents the new nonsense mutation (p.Arg151*) detected in the present case (scale: 1 pixel = 1 amino acid).

Table 1.

Molecular and clinical features of patients with Xia-Gibbs syndrome reported so far

| Reference | Age | Gender | Variant | Effect | Developmental delay | Intellectual disability | Speech | Hypotonia | Dysmorphic | Ataxia | Sleep disturbance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This case | 17 ys | M | c.451C>T | p.Arg151* | Delayed | Yes | Delayed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 6 ys | F | c.784C>T | p.Gln262* | Walking at 3 ys | NA | Full sentence | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Murdock et al., 2019 | 52 ys | M | c.979C>T | p.Gln327* | Yes | Yes | Delayed | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Yang et al., 2015 | 4 ys | F | c.1122dupC | p.Gly375Argfs*3 | Walking at 20 mo | Yes | Single words | Yes | No | Yes | NA |

| Bosch et al., 2016 | 12 ys | F | c.1402dupT | p.Cys468Leufs*49 | Yes | NA | First words at 4 yrs | NA | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Yang et al., 2015 | 16 ys | F | c.1480 A>T | p.Lys494* | NA | Yes | No verbal speech | No | Yes | No | NA |

| Díaz-Ordoñez et al., 2019 | 13 ys | F | c.1529delG | p.Gly510Alafs*12 | No walking difficulties | NA | Delayed, first monosyllables at 18 mo | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Ritter et al., 2018 | 24 ys | M | c.1759C>T | p.Arg587* | Motor delay, walking at 19 mo | Yes | Delayed | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| Yang et al., 2015 | 5 ys | M | c.1881delG | p.Gln627Hisfs*105 | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Yang et al., 2015 | 2 ys | M | c.1945delG | p.Ala649Profs*83 | No independent walking | NA | No verbal speech | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| García-Acero and Acosta, 2017 | 8 ys | F | c.2030_2030del | p.Gly677Alafs*55 | Sitting at 12 mo, walking at 28 mo | Yes | Single words | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 20 ys | F | c.2062C>T | p.Arg688* | Walking at 22 mo | NA | No sentence, but more than 50 words | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 13 ys | M | c.2229delG | p.Ser744Profs*188 | Walking at 3 ys | NA | No words | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Xia et al., 2014 | 18 mo | F | c.2373_2374delTG | p.Cys791Trpfs*57 | No sitting | NA | No words | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Xia et al., 2014 | 8 ys | M | c.2373_2374delTG | p.Cys791Trpfs*57 | Sitting at 9 mo, walking at 18 mo | Yes | First words after 1 yr, persistent speech therapy | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Yang et al., 2015 | 5 ys | M | c.2373_2374delTG | p.Cys791Trpfs*57 | Walking at 2 ys | Yes | 2 word sentences | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 21 ys | M | c.2373_2374delTG | p.Cys791Trpfs*57 | No independent walking | NA | No sentence, but more than 50 words | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 6 ys | F | c.2415delG | p.Leu806Trpfs*126 | Walking at 2 ys | NA | Full sentence | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Ritter et al., 2018 | 14 ys | F | c.2473C>T | p.Gln825* | Motor delay, walking at 3 ys | Yes | Delayed | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 9 ys | M | c.2520delT | p.Arg841Alafs*91 | No independent walking | NA | No words | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Yang et al., 2015 | 7 ys | F | c.2529_2545del17 | p.Asp845Argfs*40 | Walking at 3 ys, 10 mo | Yes | 2 to 3-word sentences | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Xia et al., 2014 | 11 ys | M | c.2547delC | p.Ser850Profs*82 | Sitting at 15 mo, no independent ambulation | Yes | No words | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 10 ys | M | c.2644C>T | p.Gln882* | Walking at 3 ys | NA | No words | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 4 ys | F | c.2691delA | p.Val898Trpfs*34 | Walking at 2.5 ys | NA | Less than 50 words | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 6 ys | F | c.2773C>T | p.Arg925* | Walking at 2 ys 4 mo | NA | Less than 50 words | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 3 ys | M | c.2773C>T | p.Arg925* | No independent walking | NA | No words | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Ritter et al., 2018 | 12 ys | M | c.2885dupC | p.Pro963fs | Motor delay, walking at 5.5 ys | Yes | Delayed | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| Xia et al., 2014 | 4 ys | F | c.2898delC | p.Tyr967Thrfs*175 | Sitting at 19 mo, walking at 24 mo | Yes | 2 words | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 6 ys | F | c.2908C>T | p.Gln970* | Walking at 2.5 ys | NA | Full sentence | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 11 ys | F | c.2908C>T | p.Gln970* | Walking at 2 ys | NA | Full sentence | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 2 ys | M | c.3773C>G | p.Ser1258* | No independent walking | NA | No words | No | NA | No | Yes |

| Yang et al., 2015 | 9 ys | M | c.3809delA | p.Gln1270Argfs*75 | Walking at 4 ys, 9 mo | Yes | No verbal speech | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Popp et al., 2017 | NA | NA | c.3814C>T | p.Arg1272* | NA | Yes | NA | NA | Yes | NA | NA |

| Jiang et al., 2018 | 17 ys | M | c.3989C>A | p.Ser1330* | Walking at 19 mo | NA | No words | Yes | NA | No | No |

| Ritter et al., 2018 | 29 ys | M | c.4494dupG | p.Cys1499Valfs*9 | Motor delay, walking at 3 ys | Yes | Delayed | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| Park et al., 2017 | 1 ys | M | hg18 del 1p36.11p35.3 (27,750,155 – 28,754,771) | NA | Yes | NA | Delayed | Yes | NA | NA | NA |

| Ritter et al., 2018 | 8 mo | F | hg19 arr 1p36.11p35.3 (27,916,308 – 28,273,494)×1 | NA | Motor delay | NA | Delayed | Hypertonia | Yes | NA | NA |

The cases were sorted according to cDNA location of the variant. mo, months; NA, not available; ys, years.

The mechanisms by which mutations in AHDC1 cause disease are still under debate. Because XGS is an autosomal dominant disorder and all mutations occur in only one coding exon, Xia et al. [2014] proposed a negative dominance mechanism. However, haploinsufficiency currently seems to be a more likely explanation, since deletions involving AHDC1 and translocation with a breakpoint in this gene have also been described in patients with clinical features of XGS [Quintero-Rivera et al., 2015; Park et al., 2017; Ritter et al., 2018].

The role of the human AHDC1 gene is still poorly understood, and much of what is known is due to the studies of patients with XGS. Structurally, this gene has 7 exons, of which only 1 (exon 6) participates in encoding the 1,603 amino acid protein AHDC1 (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the protein AHDC1 has 2 AT-hook DNA-binding motifs located in 1 conserved region at codons 396-408 and 544-556, which are known to participate in the binding of other proteins to AT-rich sequences in DNA and facilitate DNA structure changes [Aravind and Landsman, 1998; Xia et al., 2014]. AHDC1 also contains another evolutionarily conserved AT-hook domain, which contains no known functional property. Other known domains are similar to KIAA2022, a target for truncated mutations that cause intellectual alteration, and REV3L, a protein involved in DNA repair and genomic stability [Gan et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2018]. We hypothesize that a good way to elucidate these mechanisms is through the study of AHDC1 interaction partners, which must be implicated in human neurogenesis and neurodevelopment.

In conclusion, our results expand the spectrum of AHDC1 pathogenic variants associated with XGS, a possibly underdiagnosed genetic syndrome. As for the phenotype, in agreement with previous reports, our case shows that XGS is much more a nonspecific developmental disorder rather than a recognizable syndrome. The disease should be considered as a differential diagnosis of moderate to severe intellectual disability and childhood-onset behavior disorder in any age range, particularly when associated with mild dysmorphic features, sleep apnea, scoliosis, or ataxia.

Statement of Ethics

Written consent for this case report was obtained from the patient's guardian. The study was approved by the Hospital de Clinicas de Porto Alegre.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.C.C.d.S., T.O.S, F.d.O.P., T.W.K., J.A.M.S., L.S.F. Writing and original draft preparation: A.C.C.d.S., A.A.B., T.O.S., L.S.F. Critical review: F.d.O.P., A.S.F., A.A.B., T.W.K., J.A.M.S., L.S.F. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data and approved the manuscript in its final form.

Acknowledgment

We thank the patient and his family for participating in this study.

References

- 1.Aravind L, Landsman D. AT-hook motifs identified in a wide variety of DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998 doi: 10.1093/nar/26.19.4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch DG, Boonstra FN, de Leeuw N, Pfundt R, Nillesen WM, et al. Novel genetic causes for cerebral visual impairment. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:660–665. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Díaz-Ordoñez L, Ramirez-Montaño D, Candelo E, Cruz S, Pachajoa H. Syndromic intellectual disability caused by a novel truncating variant in AHDC1: a case report. Iran J Med Sci. 2019;44:257–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, Hart RK, Greenblatt MS, et al. HGVS Recommendations for the Description of Sequence Variants: 2016 Update. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:564–569. doi: 10.1002/humu.22981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gan GN, Wittschieben JP, Wittschieben BØ, Wood RD. DNA polymerase zeta (pol ζ) in higher eukaryotes. Cell Res. 2008;18:174–183. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García-Acero M, Acosta J. Whole-exome sequencing identifies a de novo AHDC1 mutation in a Colombian patient with Xia-Gibbs syndrome. Mol Syndromol. 2017;8:308–312. doi: 10.1159/000479357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang Y, Wangler MF, McGuire AL, Lupski JR, Posey JE, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of Xia-Gibbs syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2018;176:1315–1326. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller KA, Twigg SR, McGowan SJ, Phipps JM, Fenwick AL, et al. Diagnostic value of exome and whole genome sequencing in craniosynostosis. J Med Genet. 2017;54:260–268. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murdock DR, Jiang Y, Wangler M, Khayat MM, Sabo A, et al. Xia-Gibbs syndrome in adulthood: a case report with insight into the natural history of the condition. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2019;5:a003608. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a003608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park HY, Kim M, Jang W, Jang DH. Phenotype of a patient with a 1p36.11-p35.3 interstitial deletion encompassing the AHDC1. Ann Lab Med. 2017;37:563–565. doi: 10.3343/alm.2017.37.6.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popp B, Ekici AB, Thiel CT, Hoyer J, Wiesener A, et al. Exome Pool-Seq in neurodevelopmental disorders. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:1364–1376. doi: 10.1038/s41431-017-0022-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quintero-Rivera F, Xi QJ, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Lee JH, Higgins AW, et al. MATR3 disruption in human and mouse associated with bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation and patent ductus arteriosus. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:2375–2389. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritter AL, McDougall C, Skraban C, Medne L, Bedoukian EC, et al. Variable clinical manifestations of Xia-Gibbs syndrome: findings of consecutively identified cases at a Single Children's Hospital. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2018;176:1890–1896. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.40380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stenson PD, Ball EV, Mort M, Phillips AD, Shiel JA, et al. Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD): 2003 update. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:577–581. doi: 10.1002/humu.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trujillano D, Bertoli-Avella AM, Kumar Kandaswamy K, Weiss ME, Köster J, et al. Clinical exome sequencing: results from 2819 samples reflecting 1000 families. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017a;25:176–182. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trujillano D, Oprea GE, Schmitz Y, Bertoli-Avella AM, Abou Jamra R, Rolfs A. A comprehensive global genotype-phenotype database for rare diseases. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2017b;5:66–75. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia F, Bainbridge MN, Tan TY, Wangler MF, Scheuerle AE, et al. De novo truncating mutations in AHDC1 in individuals with syndromic expressive language delay, hypotonia, and sleep apnea. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:784–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H, Douglas G, Monaghan KG, Retterer K, Cho MT, et al. De novo truncating variants in the AHDC1 gene encoding the AT-hook DNA-binding motif-containing protein 1 are associated with intellectual disability and developmental delay. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2015;1:a000562. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]