Abstract

Objectives

To describe the spectrum of clinical and histopathological features of a case series of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with spontaneous regression and to discuss this phenomenon.

Method

Four cases of BCC with complete/substantial regression were retrospectively identified. Patients' records were analyzed for demographic data, clinical appearance, and the postoperative course. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens were routinely processed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and periodic acid Schiff.

Results

Complete (n = 1) or partial (n = 3) regression of BCC was observed in 4 patients. Two lesions at the medial canthus were histologically diagnosed as nodular BCC with significant regression. One lesion at the lower eyelid exhibited a complete regression which did not require surgical intervention. The other lesion at the lower eyelid presenting with ulceration and madarosis was excised. Scar tissue without evidence for a neoplasm was present histologically. Subsequently, the patient developed a recurrence with a histologically proven micronodular BCC.

Conclusions

BCC can show spontaneous substantial or complete regression. Histological tumor absence in lesions which are clinically suspicious for a neoplasm can be a hint for a regressive BCC. Recurrences may develop from remaining tumor islands warranting periodical clinical visits in cases of clinically as well as histologically suspected regressive BCC.

Keywords: Basal cell carcinoma, Tumor regression, Histology, T lymphocytes

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequent malignant tumor of the ocular adnexa [1]. It is considered semimalignant as it usually does not metastasize. Although slowly growing, the tumor is locally aggressive. The most frequent localization within the ocular adnexa is the lower eyelid or the medial canthus region [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Different subtypes of BCC can be distinguished with the nodular and morpheaform (sclerosing) subtype being the most significant ones for ophthalmologists [2, 6].

Clinically, nodular BCC is characterized by a circumscribed elevated lesion with rolled pearly edges, telangiectasia, and a central ulceration. The sclerosing subtype is not well-defined and may have a whitish to yellowish plaque-like appearance. If the eyelids are affected, focal madarosis and ulceration are usually present.

Histologically, nodular BCC is composed of nests of monomorphic basophilic tumor cells with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. Palisading of peripheral tumor cells as well as retraction artifacts are typically observed. There are no intercellular bridges. Mitotic figures can be frequent. The tumor is usually surrounded by thickened collagenous stroma (pseudocapsule) and an inflammatory cell infiltrate. The sclerosing subtype is composed of strands of basaloid cells infiltrating the surrounding tissue. The lesion is poorly demarcated. Classical histological features of nodular BCC such as peripheral palisading and retraction artifacts (due to processing-related tissue shrinkage) are often not identified. Sometimes, both subtypes are present within one lesion. The inflammatory cell infiltrate surrounding the tumor is composed of CD4+ T-lymphocytes (in particular regulatory T cells) and macrophages [2, 7, 8].

Complete surgical excision of a lesion remains − despite the recent introduction of other nonsurgical treatment modalities − the gold standard for BCC of the ocular adnexa [9]. Up to now, only 2 cases of BCC with regression (spontaneously and after biopsy, respectively) of the ocular adnexa have been reported [10, 11].

In this study, clinical and histopathological features of four BCC with complete or incomplete (but substantial) tumor regression are presented. Based on the clinical and histological spectrum of findings and the clinical course, recommendations on treatment and follow-up of patients with a presumed regressive BCC are provided. The knowledge and correct interpretation of this phenomenon is particularly important for oculoplastic surgeons, oncologists, and (ophthalmic) pathologists in order to avoid misdiagnosis and underestimation of this locally aggressive tumor.

Materials and Methods

All specimens with significant regression of BCC between 1998 and 2018 were identified retrospectively at the Ophthalmic Pathology Laboratory Bonn (n = 3). Another patient exhibited complete clinical regression. The medical records of the corresponding patients were retrospectively reviewed with regard to patient's history, age, gender, localization and clinical appearance of the lesion, treatment, and outcome. Submitted in 4% paraformaldehyde, the specimens were routinely processed for light microscopic examination and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and periodic acid-Schiff. Immunohistochemical stains for CD4 (monoclonal mouse anti-human CD4, clone 4B12, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark; dilution 1:40), CD20 (monoclonal mouse anti-human CD20, clone L26, DAKO; dilution 1:200), and CD68 (monoclonal mouse anti-human CD68, clone PG-M1, DAKO; dilution 1:50) were performed in 2 cases (case 1, case 2) to further characterize the inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Results

Four BCC with spontaneous regression were observed between 1998 and 2018 at the University Eye Hospital Bonn. The male:female ratio was 1:1. Two lesions occurred at the lower eyelid margin, the other two at the medial canthus. Three lesions were classified as nodular BCC (with two of them exhibiting histological signs of active regression and the other a complete clinical regression). The respective patients suffered from hyperlipidemia which was treated by statins. The fourth lesion was classified as partially micronodular BCC and was the only one showing histological characteristics of previous regression.

The clinical course and histological picture of the 4 cases (Table 1) are described below.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of the patients

| Case | Age, years | Gender | Localization | Clinical features | Histological features | Follow-up | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 74 | Male | Medial canthus OD | Nodular tumor with partial clinical regression | Partial tumor regression | 30 months | No |

| 2 | 87 | Male | Medial canthus OD | Nodular tumor | Partial tumor regression | 9 months | No |

| 3 | 79 | Female | Lower eyelid OS | Nodular tumor with complete clinical regression | N/A | 18 months | No |

| 4 | 75 | Female | Lower eyelid OD | Ulceration with madarosis | Scar tissue | 42 months | Yes (histologically proven multifocal/partly micronodular BCC) |

Patient 1 − Substantial Clinical and Histological Regression of BCC

Ophthalmologic History. A 74-year-old man presented with a nodular lesion at the medial canthus with a 12-month history of growth. At the first visit, the tumor revealed a central ulceration and telangiectatic vessels (Fig. 1a). As the lesion was highly suspicious for BCC, the patient was scheduled for surgery. Three months later, when the patient presented for surgery, he reported a slight reduction in tumor size. Indeed, the lesion had slightly decreased in size but was still present with an accompanying focal redness (Fig. 1b). Thus, the patient underwent surgery, and the tumor was completely excised (R0 resection). Within 30 months of follow-up, no recurrence was observed.

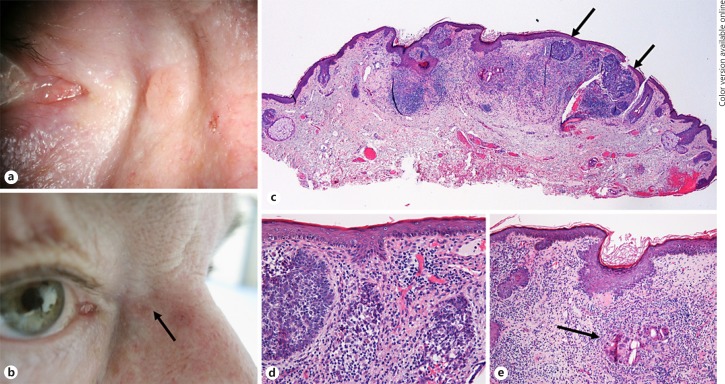

Fig. 1.

aPatient 1 with a typical aspect of a nodular BCC in the medial canthus with telangiectasia and pearly appearance at the patient's first visit. bPicture of the same patient 3 months later immediately before surgery. The lesion has markedly decreased in size. A focal redness was observed. cHistologic picture illustrating the excised lesion which revealed some residual tumor island composed of basaloid cells (arrows). The main part of the lesion, however, consisted of an inflammatory cell infiltrate. dHigher magnification of C illustrating remnants of tumor cell nests which are infiltrated by inflammatory cells. eHigher magnification of C illustrating foreign body giant cells (arrow) possibly digesting the tumor cells.

Histopathological Findings. The excised tissue (7 × 6 × 3 mm in size) was covered by keratinized squamous epithelium. There were small islands of basophilic tumor cells present with the outer cells arranged in palisades (Fig. 1c). Shrinkage artifacts were also present. However, the main part of the lesion was composed of a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. The cells were mainly positive for CD4 (T lymphocytes) and CD68 (macrophages; online suppl. Fig. 1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000501370). CD20-positive B-lymphocytes were only present in the periphery of the lesion. The inflammatory cells were invading the tumor cell nests in some areas (Fig. 1d). There were also foreign body giant cells present in other areas which seemed to digest tumor cells (Fig. 1e). The lesion was accompanied by solar elastosis. Scar tissue was not present. The surgical margins were free of tumor.

General History. The patient suffered from arterial hypertension, cardiac arrhythmia, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus type 2. He was under medication with amlodipine, enalapril, pravastatin, and insulin.

Patient 2 − Histological Regression of BCC

Ophthalmologic History. An 87-year-old man presented with a growing nodule suspicious for BCC. A nodule with a massive central ulceration was seen in the medial canthus area (Fig. 2a). Thus, the patient was scheduled for surgery. The lesion was completely excised and a free graft from the ipsilateral upper eyelid was used to cover the defect. After 9 months, the patient was lost to follow-up.

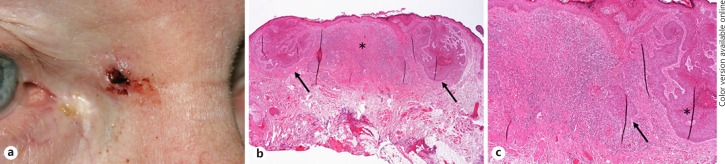

Fig. 2.

aPatient 2 with a tumor in the medial canthus area with central ulceration and rolled edges highly suspicious for BCC. bThe histologic picture shows a completely excised basaloid tumor (arrows) arising from the epithelium. The center of the lesion is completely occupied by a chronic lymphoplasmacellular infiltrate (asterisk, H&E stain). cHigher magnification of b illustrating the BCC (asterisk) and the inflammatory cell infiltrate which invades a tumor nest (arrow).

Histopathological Findings. The excised tissue (8 × 8 × 4 mm in size) was covered by keratinized squamous epithelium. Emanating from the epithelium was a lesion composed of islands of basophilic tumor cells (Fig. 2b). The outer cells were arranged in palisades. Shrinkage artifacts were present. The central part of the lesion was mainly composed of a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. Only remnants of tumor were present in this area. The inflammatory cells were mainly positive for CD4 (T lymphocytes), CD20 (B lymphocytes) and CD68 (macrophages; online suppl. Fig. 1). The inflammatory cells were invading the tumor cell nests towards the periphery (Fig. 2c). Scar tissue was not present. The surgical margins were free of tumor.

General History. The patient suffered from arterial hypertension, artrial fibrillation, hyperlipidemia, hypothyreosis, and gout. Furthermore, the patient had an artificial heart valve.

The patient was under systemic medication with apixaban, levothyroxine, olmesartan, pravastatin, bisoprolol, allopurinol, and enalapril/lercanidipine.

Patient 3 − Complete Clinical Regression of BCC

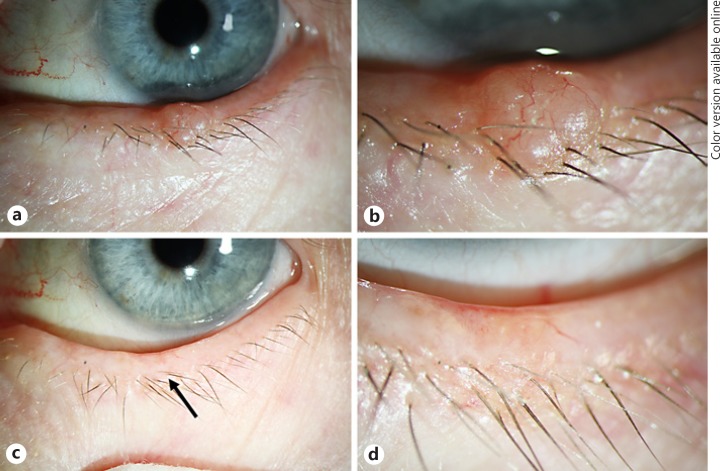

Ophthalmologic History. A 79-year-old woman presented with a nodule on her left lower eyelid with a 3-month history of growth. At her first visit, a well-demarcated nodule was seen with a slight central ulceration and telangiectatic vessels (Fig. 3a, b). As the lesion was suspicious for BCC, the patient was scheduled for surgery. Three months later, when she presented for surgery, the lesion had disappeared without any external intervention. There was only a minimal ulceration and redness as well as a larger blood vessel in the area of the former tumor (Fig. 3c, d). The surgery was cancelled, and the patient agreed to come regularly for follow-up visits. The lesion did not recur within 18 months of follow-up.

Fig. 3.

a Patient 3 with a nodular tumor at the lower eyelid margin with telangiectasia typical for BCC. bHigher magnification of a. c Eyelid margin with minimal telangiectasia (arrow) 18 months after the initial presentation without any surgical or nonsurgical treatment indicating a spontaneous regression. d Higher magnification of c.

General History. The patient suffered from arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyreosis and had survived a myocardial infarction. The patient was under systemic medication with aspirin 100, isosorbide mononitrate, molsidomin, amlodipine, metoprolol atorvastatin, candesartan, and levothyroxine.

Patient 4 − Regression of BCC with Local Recurrence

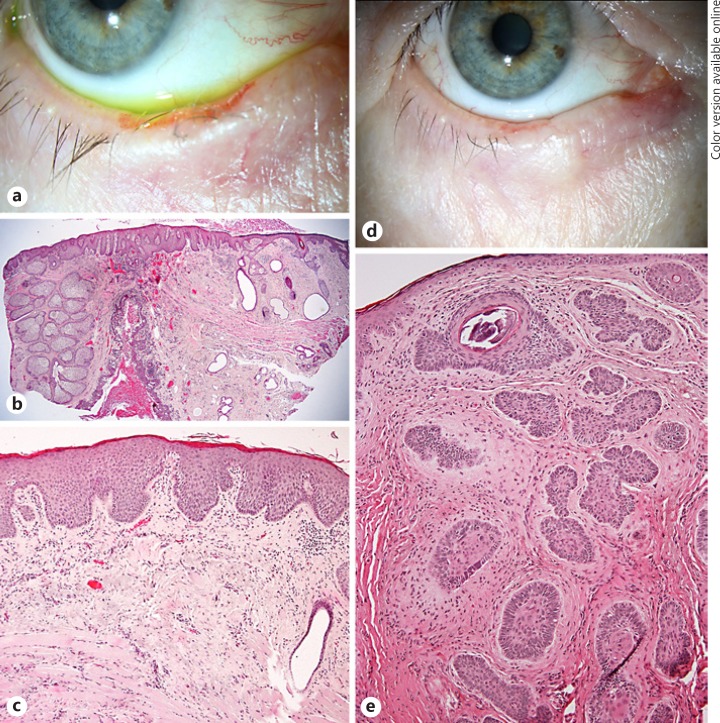

Ophthalmologic History and Histopathological Findings. A 75-year-old patient presented with a growing ulceration at the right lower eyelid. She had a history of BCC at the nose. At her first visit, besides pterygium OU, an ulceration with rolled edges of the lower eyelid margin was detected (Fig. 4a). Suspicious for a neoplasm (in particular BCC), a wedge resection was performed. Histological analysis of the lesion failed to detect a tumor in step sections. However, scar tissue was present (Fig. 4b, c). Forty-five serial sections cut in further preparation of this case study revealed focal epidermal changes in a few slides. Small basaloid proliferations were seen to arise from the epithelium suspicious for developing BCC. There was an inflammatory cell infiltrate present adjacent to these foci. However, no unequivocal BCC nests were detected (online suppl. Fig. 2). The patient underwent further follow-up controls and was treated for blepharitis due to a persisting “suspicious” aspect of the lower eyelid. 18 months later, a subcutaneous thickening was detected (Fig. 4d), and the patient was again scheduled for a wedge resection. Histological analysis this time revealed small nodules of basaloid cells surrounded by a myxoid stroma (Fig. 4e). The diagnosis of a partially micronodular BCC was made, and the patient underwent two-step R0 resection. No recurrence was observed within 24 months of follow-up.

Fig. 4.

a Patient 4 with an ulcerated lesion of the lower eyelid highly suspicious for a neoplasm. b A wedge resection was performed showing a regular eyelid architecture after horizontal dissection. c Higher magnification revealed scar tissue without any evidence for BCC in several step sections. d During follow-up (1.5 years later), the patient developed a recurrent ulceration and diffuse eyelid thickening. eThe histologic evaluation of the repeat wedge resection revealed a partially micronodular BCC with small nests exhibiting peripheral palisading surrounded by a myxoid stroma. Retraction clefts were also present as well as focal regressive changes (calcification).

General History. The patient suffered from arterial hypertension and depression. The patient was under systemic medication with ramipril, lercanidipine, and trimipramine.

Discussion/Conclusion

BCC of the ocular adnexa is a semimalignant tumor which is removed by surgical excision. In contrast to keratoacanthoma which frequently exhibits extensive clinical regression [12], this phenomenon is hardly observed in BCC. Herein, we describe 4 cases with a spontaneous substantial or complete tumor regression (namely a replacement of tumor by inflammatory cells or scar tissue without a clinically significant tumor shrinkage in 3 cases and a complete clinical regression in 1 case) and different clinical courses.

Active versus Previous Regression in BCC

Partial tumor regression of BCC has been described before in histological specimens [13, 14, 15, 16]. However, these studies reported only focal changes without any significant clinical relevance, usually not exceeding more than 1 high power field [14]. Such histological regression was found in 20% [14] up to 85% [16] of BCC. Two different types of regression can be distinguished: active regression and evidence of previous regression [14]. Active regression is defined by disruption of the regular architecture of the tumor islands with the tumor nests being surrounded and infiltrated by an inflammatory cell infiltrate. Apoptotic tumor cells may also be present. Previous regression is, according to Curson and Weedon [14], characterized by the presence of scar tissue with new collagen formation, a reduction of skin appendages, an increased number of blood vessels and a lymphoplasmacellular infiltrate. These histological findings may be associated with clinically observed scarring in large skin (not ocular adnexa) BCC [16]. Proliferation and subsequent regression (associated with stroma remodeling) were suggested to be responsible for the slow clinical growth of BCC [13].

Extensive active regression was found in our cases 1 and 2. For comparison, a case of focal regression is added as supplemental Figure 3. Case 4 represents a typical example of an extensive previous regression.

Further Cases of Significant Tumor Regression

There are only a few reported cases of significant clinical tumor regression in BCC of the ocular adnexa. A tumor at the lower eyelid in a 93-year-old female patient which was clinically diagnosed as BCC due to its characteristic features had nearly completely disappeared within 5 months. Only a small hyperpigmented skin macule was present. The patient denied a surgical procedure and remained under follow-up [10]. Another case report described a complete regression within 6 months after biopsy of a nodular BCC. No further surgery was performed. No recurrence was observed within 4 years of follow-up [11]. Regressive BCC was described in other locations than the ocular adnexa and in association with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, too [17, 18].

Regression in BCC may also occur after surgical or therapeutic actions: complete regression may follow an incomplete resection or a diagnostic biopsy [19, 20]. In particular, the latter scenario is often observed by the authors in their outpatient clinic. Patients which are referred for R0 resection of a biopsy-proven BCC often show no or nearly no signs of a residual tumor. In these instances, a close follow-up is recommended as well as a precise photodocumentation. Thus, we do not recommend a biopsy in clinically typical BCC. In cases in which a biopsy is inevitable, a thorough photodocumentation of the tumor and the site of biopsy is mandatory. Sutures may also be used for small biopsy defects as they may be left as “marker” until the final surgery is performed. A diagnostic biopsy without the intention to conduct the following treatment should be strongly avoided.

An established topical therapy leading to regression of superficial or small nodular BCC is imiquimod 5%. It results in an increased apoptotic rate of tumor cells as well as an immunological response via CD3+/CD4+ lymphocytes and dendritic cells/macrophages [21, 22, 23]. Although reported with a good outcome in patients with periocular BCC, the topical application for BCC of the ocular adnexa is problematic due to extensive local inflammation and the risk for severe ocular surface complications [24].

For further discussion of pathogenetic aspects(including the role of the local inflammatory environment as well as possible systemic factors such as systemic diseases and medication) [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35] see online supplementary material.

Management of Regressive BCC

This case series adds another 4 cases of spontaneously regressive BCC to the few previously described cases highlighting that this phenomenon is rare and does not generally justify a nonsurgical approach. However, based on these 4 cases, suggestions for the therapeutic management of these patients are provided and discussed.

The treatment (and follow-up) of BCC with a suspected partial regression (case 1 and 2) does not differ from that of “regular” BCC, in particular as the regression was detected mainly histologically and no significant tumor shrinkage was observed clinically. As the ocular adnexa are considered a high-risk site for recurrences [9], a complete surgical excision should be aimed for. Case 1 highlights that local inflammatory changes do not exclude the coexistence a neoplasm.

However, in patients with complete clinical regression (case 3), it may be considered to refrain from surgery if follow-up visits are warranted. A surgical approach is an option in order to exclude remnants of a neoplasm. However, in particular at the lid margin, abnormal findings indicating a recurrence after previous regression can be detected very early allowing for adequate surgical treatment.

Patients with histological tumor absence in lesions which clinically are highly suspicious for a neoplasm (case 4) need to undergo close follow-up visits and re-biopsy in unequivocal cases. This applies also to cases with only a small biopsy that may not be representative of the entire lesion. Step sections should be performed by the ophthalmic pathologist to look for evidence of a definite neoplasm [36]. Special attention should also be given to scar formation which may be an indication of a previous regression. Histologically, a scar formation in regressive BCC may also be mistaken for a benign lichenoid keratosis underestimating the malignant potential of the lesion [37]. From our experience, serial sections (which showed focal epithelial irregularities suggestive of developing BCC foci in some sections in our case 4) did not add more information to the case and would retrospectively not have changed the management of this case. Thus, serial sections are not mandatory but may be considered under certain circumstances. In the past, we have observed a few patients with larger ulcerated lesions at the lower eyelid (similar to case 4) exhibiting histologically relatively small foci of BCC surrounded by inflammatory cells and scarring [38]. These lesions may retrospectively also be interpreted as incomplete regression.

In conclusion, BCC may exhibit partial or complete regression showing that local inflammatory processes may not exclude the coexistence of a malignant lesion. In cases which are clinically suspicious for a neoplasm despite histological tumor absence, regressive BCC should be considered. However, recurrences may arise from an incomplete regression with remaining tumor islands warranting periodical clinical follow-up visits for these patients. The underlying pathophysiological mechanism may be attributed to the inflammatory micromilieu.

Statement of Ethics

Ethics Committee approval was obtained. Research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

None.

Author Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to the manuscript (see below). All authors approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

M.C.H.C.: Conception, case acquisition, analysis, interpretation, writing.

K.U.L.: Case acquisition, analysis, interpretation, revision.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Allali J, D'Hermies F, Renard G. Basal cell carcinomas of the eyelids. Ophthalmologica. 2005 Mar-Apr;219((2)):57–71. doi: 10.1159/000083263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser U, Loeffler KU, Nadal J, Holz FG, Herwig-Carl MC. Polarization and Distribution of Tumor-Associated Macrophages and COX-2 Expression in Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Ocular Adnexae. Curr Eye Res. 2018 Sep;43((9)):1126–35. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2018.1478980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soysal HG, Soysal E, Markoç F, Ardiç F. Basal cell carcinoma of the eyelids and periorbital region in a Turkish population. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 May-Jun;24((3)):201–6. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31816d954d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben Simon GJ, Lukovetsky S, Lavinsky F, Rosen N, Rosner M. Histological and clinical features of primary and recurrent periocular Basal cell carcinoma. ISRN Ophthalmol. 2012 Apr;2012:354829. doi: 10.5402/2012/354829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malhotra R, Huilgol SC, Huynh NT, Selva D. The Australian Mohs database, part II: periocular basal cell carcinoma outcome at 5-year follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2004 Apr;111((4)):631–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. Study of a series of 1039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990 Dec;23((6 Pt 1)):1118–26. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70344-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rohrbach JM, Stiemer R, Mayer A, Riedinger C, Duijvestijn A, Zierhut M. Immunology and growth characteristics of ocular basal cell carcinoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001 Jan;239((1)):35–40. doi: 10.1007/s004170000221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omland SH, Nielsen PS, Gjerdrum LM, Gniadecki R. Immunosuppressive Environment in Basal Cell Carcinoma: The Role of Regulatory T Cells. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016 Nov;96((7)):917–21. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015 Jun;88((2)):167–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young-Zvandasara T, Popiela M, Shuttleworth G. ‘The nodule that disappeared’ spontaneous regression of an eyelid noduloulcerative lesion mimicking the features of a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Jan;2015:bcr2014206566. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-206566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta M, Puri P, Kamal A, Nelson ME. Complete spontaneous regression of a basal cell carcinoma. Eye (Lond) 2003 Mar;17((2)):262–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Jun;74((6)):1220–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franchimont C, Pierard GE, Van Cauwenberge D, Damseaux M, Lapiere CH. Episodic progression and regression of basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 1982 Mar;106((3)):305–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curson C, Weedon D. Spontaneous regression in basal cell carcinomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1979 Oct;6((5)):432–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1979.tb01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnetson RS, Halliday GM. Regression in skin tumours: a common phenomenon. Australas J Dermatol. 1997 Jun;38((S1 Suppl 1)):S63–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1997.tb01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt MJ, Halliday GM, Weedon D, Cooke BE, Barnetson RS. Regression in basal cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical analysis. Br J Dermatol. 1994 Jan;130((1)):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb06873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujimura T, Kakizaki A, Kambayashi Y, Aiba S. Basal cell carcinoma with spontaneous regression: a case report and immunohistochemical study. Case Rep Dermatol. 2012 May;4((2)):125–32. doi: 10.1159/000339621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McPherson T, Ogg G. Spontaneous resolution of basal cell carcinoma in naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome/Gorlin's syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009 Dec;34((8)):e884–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rieger UM, Schlecker C, Pierer G, Haug M. Spontaneous regression of two giant basal cell carcinomas in a single patient after incomplete excision. Tumori. 2009 Mar-Apr;95((2)):258–63. doi: 10.1177/030089160909500223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swetter SM, Boldrick JC, Pierre P, Wong P, Egbert BM. Effects of biopsy-induced wound healing on residual basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas: rate of tumor regression in excisional specimens. J Cutan Pathol. 2003 Feb;30((2)):139–46. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.000002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnetson RS, Satchell A, Zhuang L, Slade HB, Halliday GM. Imiquimod induced regression of clinically diagnosed superficial basal cell carcinoma is associated with early infiltration by CD4 T cells and dendritic cells. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004 Nov;29((6)):639–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urosevic M, Maier T, Benninghoff B, Slade H, Burg G, Dummer R. Mechanisms underlying imiquimod-induced regression of basal cell carcinoma in vivo. Arch Dermatol. 2003 Oct;139((10)):1325–32. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.10.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Giorgi V, Salvini C, Chiarugi A, Paglierani M, Maio V, Nicoletti P, et al. In vivo characterization of the inflammatory infiltrate and apoptotic status in imiquimod-treated basal cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2009 Mar;48((3)):312–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Martin E, Idoipe M, Gil LM, Pueyo V, Alfaro J, Pablo LE, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of imiquimod 5% cream to treat periocular basal cell carcinomas. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010 Aug;26((4)):373–9. doi: 10.1089/jop.2010.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halliday GM, Patel A, Hunt MJ, Tefany FJ, Barnetson RS. Spontaneous regression of human melanoma/nonmelanoma skin cancer: association with infiltrating CD4+ T cells. World J Surg. 1995 May-Jun;19((3)):352–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00299157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong DA, Bishop GA, Lowes MA, Cooke B, Barnetson RS, Halliday GM. Cytokine profiles in spontaneously regressing basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 2000 Jul;143((1)):91–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buechner SA, Wernli M, Harr T, Hahn S, Itin P, Erb P. Regression of basal cell carcinoma by intralesional interferon-alpha treatment is mediated by CD95 (Apo-1/Fas)-CD95 ligand-induced suicide. J Clin Invest. 1997 Dec;100((11)):2691–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI119814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voorneveld PW, Reimers MS, Bastiaannet E, Jacobs RJ, van Eijk R, Zanders MM, et al. Statin Use After Diagnosis of Colon Cancer and Patient Survival. Gastroenterology. 2017 Aug;153((2)):470–479.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsen SB, Dehlendorff C, Skriver C, Dalton SO, Jespersen CG, Borre M, et al. Postdiagnosis Statin Use and Mortality in Danish Patients With Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Oct;35((29)):3290–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.8981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koomen ER, Joosse A, Herings RM, Casparie MK, Bergman W, Nijsten T, et al. Is statin use associated with a reduced incidence, a reduced Breslow thickness or delayed metastasis of melanoma of the skin? Eur J Cancer. 2007 Nov;43((17)):2580–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang A, Stefanick ML, Kapphahn K, Hedlin H, Desai M, Manson JA, et al. Relation of statin use with non-melanoma skin cancer: prospective results from the Women's Health Initiative. Br J Cancer. 2016 Feb;114((3)):314–20. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin BM, Li WQ, Cho E, Curhan GC, Qureshi AA. Statin use and risk of skin cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Apr;78((4)):682–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang K, Marley A, Tang H, Song Y, Tang JY, Han J. Statin use and non-melanoma skin cancer risk: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Oncotarget. 2017 Aug;8((43)):75411–7. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang A, Tang JY, Stefanick ML. Relation of statin use with non-melanoma skin cancer: Prospective results from the Women's Health Initiative. Womens Health (Lond) 2016 Sep;12((5)):453–5. doi: 10.1177/1745505716667958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt SA, Schmidt M, Mehnert F, Lemeshow S, Sørensen HT. Use of antihypertensive drugs and risk of skin cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Aug;29((8)):1545–54. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zemelman V, Silva P, Sazunic I. Basal cell carcinoma: analysis of regression after incomplete excision. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009 Oct;34((7)):e425. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kulberg A, Weyers W. Regressing basal-cell carcinoma masquerading as benign lichenoid keratosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016 Oct;6((4)):13–8. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0604a03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herwig MC, Löffler KU. Blepharitis - wann greifen wir zum Skalpell? Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2016 Jul;233((7)):813–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-105567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data