Abstract

Introduction: Diarrheal diseases are threat everywhere, but its frequency and impact are more severe in developing countries. Diarrhea occurs world-wide and causes 4% of all deaths and 5% of health loss to disability. In 2016, it was the eighth leading cause of mortality. Moreover, data from the World Health Organization indicated that diarrheal diseases are causes for an estimated 2 million deaths annually. Therefore, this study aimed to assess diarrheal diseases and associated behavioural factors. Method: An institution based cross-sectional study was conducted. A stratified random sampling method was employed to select 1050 study participants. Participants were interviewed using structured questionnaire. To analysis the data, binary logistic regression and multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted. Results: The two weeks prevalence of diarrhea was found to be 3.4%. Further, 1.6%, 10.5%, 10.7% and 9% of the food handlers had acute watery diarrhea, cough, an infection of runny nose and incidence of any fever respectively. Regular hand washing after toilet (AOR = 0.13 with 95% CI: 0.024, 0.72), using toilet while wearing protective clothes/gown (AOR = 5.39 with 95% CI; 1.59, 18.32), habit of eating raw beef and raw vegetables (AOR = 6.27 with 95% CI: 1.89–20.78), type of toilet (AOR = 4.07 with 95% CI: 0.29–6.67 were associated significantly with diarrhea. Conclusion: This assessment proved to be an essential activity for reduction of community diarrheal diseases, as a significant number of food handlers had diarrhea. Good sanitation, hygiene practice and a healthy lifestyle behavior can prevent diarrhea. A strong political commitment with appropriate budgetary allocation is essential for the control of diarrheal diseases.

Keywords: diarrheal disease, food handler, behavioural factor, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

1. Introduction

Diarrhea is defined as three or more loose or watery stools per day [1]. Diarrhea is a threat everywhere, but its frequency and impact are more severe in low-resource settings [2],[3]. It occurs world-wide and causes 4% of all deaths and 5% of health loss to disability [4]. In 2016, diarrheal diseases were the eighth leading cause of death among all ages [5]. Diarrheal diseases caused an estimated 1.3 million deaths and are the fourth leading cause of years of life lost in developing countries [6]. On a global scale, of the estimated 165 million Shigella diarrheal episodes estimated to occur each year, 99% occur in developing countries [7]. The major six pathogens responsible for diarrhea are Shigella, rotavirus, adenovirus, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (E. coli) Cryptosporidium, and Campylobacter. However, rotavirus and E. coli are the two most common etiological agents of moderate-to-severe diarrhea in low-income countries [8].

Diarrheal disease affects rich and poor, old and young, and those in developed and developing countries alike, yet a strong relationship exists between poverty and an unhygienic environment. Food-borne diseases pose a significant public health burden worldwide [9],[10]. Diarrheal diseases are the most common illnesses resulting from the consumption of contaminated food and water [11],[12]. In Africa, it is estimated that 92 million people fall ill from consuming contaminated foods, resulting in 137,000 deaths each year [13]. In developing countries, there have been several attempts to improve food safety and to reduce diarrheal disease [14]. However, insufficient access to adequate hygiene and sanitation are major risk factors for the heavy burden of diarrheal diseases in developing countries [15]. Biological contaminants, largely bacteria and parasites constitute the major causes of diarrheal diseases often transmitted through food, water, and nails, and fingers contaminated with faeces. Accordingly, food handlers with poor personal hygiene are potential sources of infections from these microorganisms [16]. Based on the distribution of use of the different types of water sources and the associated risks of diarrhea, 502,000 diarrheal deaths in low and middle income countries can be attributed to inadequate and unsafe drinking water. Of these deaths, 88% occur in Africa and South-East Asia [17]. Moreover, in 2016, impure water, inadequate sanitation and poor hygiene was responsible for 829,000 annual deaths from diarrhea, and 1.9% of the global burden of disease [18].

Though the federal government of Ethiopia launched an urban health extension program including food and water safety packages at the capital city, Addis Ababa in 2009, still the city has many health problems especially recurrent food and water borne outbreaks [19]. According to the 2016 Addis Ababa health bureau report, there is high prevalence of diarrheal diseases in Addis Ababa though its sources are not well known and studied in depth. According to the 2017 Addis Ababa Food, Medicine and Health Care Administration and Control Authority (AAFMHACA) Report, food establishments located in Addis Ababa are suspected to be major sources of diarrheal diseases which might arise from poor knowledge and practice of food handlers, poor quality of drinking water, poor waste water and solid waste management, lack of wash facilities and poor water storage conditions. Due to these and other unknown factors, the city has many health problems like a high burden of typhoid fever, amoeba, acute watery diarrhea and other diarrheal diseases. Diarrheal disease is an important public health problem, causing morbidity and mortality. However, except for verbal reports, no studies have been conducted on the health status of food handlers. Because of this, a considerable number of customers of the food establishments have been exposed to different gastro-intestinal health problems. Accordingly, this study aimed at filling the research gap on the prevalence of diarrheal disease and associated behavioral factors among food handlers in Addis Ababa.

2. Methods

2.1. Description of the study area

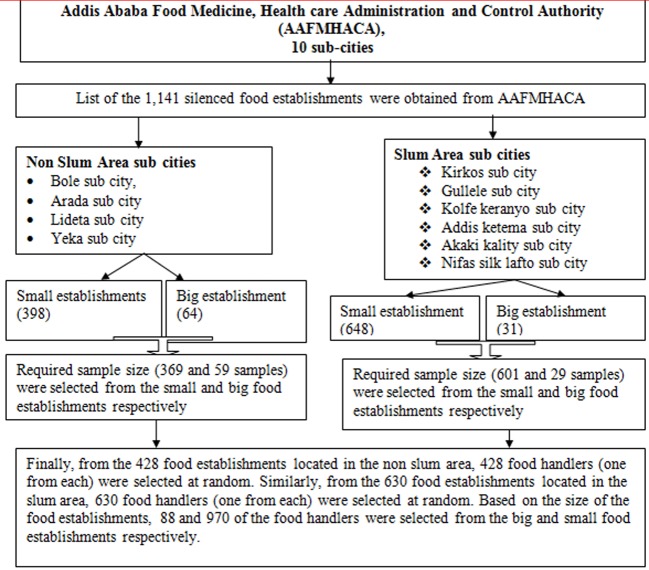

The study was conducted in Addis Ababa city located in Upper Awash River basin, the capital of the Federal Government of Ethiopia and the seat for the African Union Headquarters. According to the 2017 AAFMHACA report, there are 1141 licensed food establishments, employing 4565 food handlers. Of the total licensed food establishments, 95 (8%) are large (hotels with one or more stars) and the remaining 1046 (92%) are small food establishments which include unranked (non-star hotels, bars, restaurants, cafes etc). The location map of Addis Ababa city is depicted below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Map of Addis Ababa city administration. Source: Berhanu M, Raghuvanshi TK, Suryabhagavan K, Web-based GIS approach for tourism development in Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia [20].

2.2. Study design

An institutional based cross sectional study was conducted among food handlers of Addis Ababa city administration from June to July 2019.

2.3. Source population

All food handlers located in Addis Ababa city administration were the source population.

2.4. Study population

All selected food handlers were located in Addis Ababa.

2.5. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All 18 years and above food handlers, workings for a minimum of three months were included. However, causal food handlers were excluded.

2.6. Sample size determinations

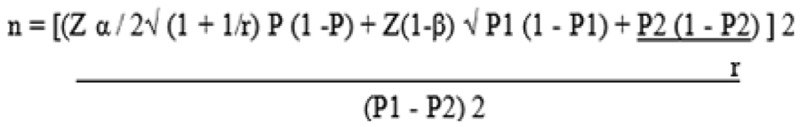

To estimate the two week prevalence of diarrheal diseases and associated behavioral factors among food handlers in the food establishments of Addis Ababa, a sample size was calculated using a two population proportion formula (EPI INFO version 7.2.2.6) considering that:

For hand washing before meals and after defecation:

P1 prevalence of diarrhea among exposed group is 16.9% and P2 prevalence of diarrhea among unexposed group is 24.1% [21].

Power to detect a significant difference between P1 and P2 if it exists (1 − β) = 80%.

Z α/2 = 95% confidence interval.

Ratio [r] = 1:1 and OR= 0.643 [21].

The weighted average of P1 and P2 =

n = sample size for hand washing before meals and after defecation.

Then, using two population proportion formula,

|

(1) |

Or EPI INFO versions 7.2, 2.6 STATCALC, 1058 sample of food handlers were included.

2.7. Sampling procedure

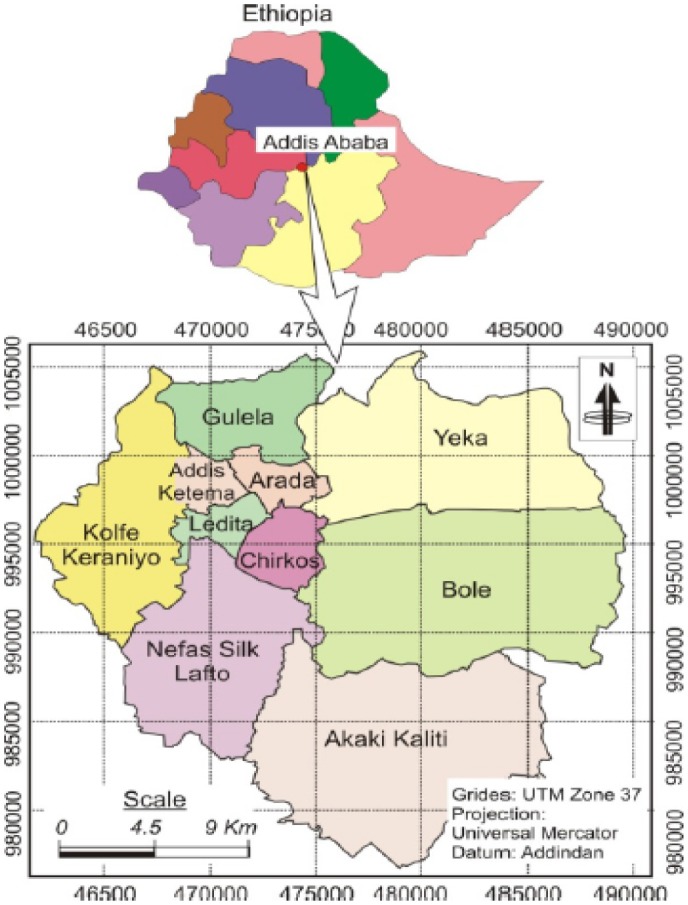

The study participants were selected using a stratified, simple random sampling technique. To collect data, a listing of the 1141 licensed food establishments was obtained from AAFMHACA. These 1141 food establishments were stratified in to slum and non-slum areas based on their location. Similarly, the food handlers were stratified into two based on their work location (slum and non-slum area). Further, food handlers working in large and small food establishments were stratified into two. Based on this, sample allocation was conducted to the slum and non-slum areas in addition to the large and small food establishments. After the food handlers were stratified based on their work location and size of food establishments (large or small), one food handler from one food establishment was selected at random. Based on this, samples from 428 and 630 food handlers were taken from the food establishments located in the non-slum and slum area respectively. From the non-slum area, 59 samples from the large/big and 369 samples from the small food establishments were collected. Also, from the slum area (630), 29 samples from the large/big and 601 samples from the small food establishments were collected. Finally, using a simple random sampling technique, 1058 food handlers were selected to assess prevalence of diarrheal diseases and associated factors. A stratified random sampling technique was used in both slum and non-slum areas as well as large and small food establishments of Addis Ababa. The main purpose of stratification was to ensure representativeness for food handlers working in different areas and in various types of establishments with different educational status and work experience. In summary, the sampling procedure for this study is depicted below in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Systematic structure of the study sampling procedure.

2.8. Data collection procedures

Data enumerators were identified based on professional capability and technical experience in collecting the required data. Accordingly, fifteen health professionals with a Bachelor of Science and extensive experience in similar data collection practices were employed. In addition, four Masters' degree holders were recruited for supervision of data collection. Two-day training was given to the data collectors and supervisors. After written consent was obtained from each study subjects, the data was collected from food handlers through face-to-face interview using a structured questionnaire.

2.9. Data quality assurance

A questionnaire was prepared in English and translated in to Amharic and back to English to maintain the consistency of questions. The quality of data was ensured through training of data collectors, close supervision, prompt feedback and daily recheck of completed questionnaire. Moreover, a brief daily activity evaluation method was established to correct problems that arose during the course of data collection. The consent and the assurance of confidentiality were ensured. The principal investigator checked and reviewed the entire completed questionnaire to ensure completeness and consistency of the information.

2.10. Data analysis

All data were checked for correctness of information and code. Date analyses were performed by using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software version 20. Descriptive statistics such as frequency (%) for categorical and mean and standard deviation for numerical data were used to sum up the data. A binary logistic regression model was fitted to assess any association between diarrhea and independent variables. P values of 0.05 and 95% confidence interval for adjusted odds ratio (AOR) were used to report statistical significance.

2.11. Operational definitions of key terms

Diarrhoea Disease: Defecation frequency of three or more loose/liquid stools in a day.

Health Status: The presence of absence of diarrheal disease in two weeks prior to the study.

Food Establishments: Institutions that provide food and drinks for selling to customers.

Food: A material consisting nutritious substances that people eat or drink in order to maintain life and growth

Food Handlers: A person who is involved in the preparation and handling of food in a food establishment.

Large/big Food Establishment: Hotels with one or more stars.

Small Food Establishment: Small vendors, non-star hotels, bars, restaurants, cafes.

Slum Area: Area with poorer sanitation infrastructure.

Non-slum Area: Area with better sanitation infrastructure.

2.12. Study variables

A: Independent or explanatory variables:

The predictor variables of this study were sex, age, marital status, religion, educational status, length of work experience of the food handlers etc.

B: Dependent or outcome or response variables:

Outcome of this study was diarrheal disease.

2.13. Ethical consideration

Firstly, a letter of support was obtained from the Ethiopian Institution of Water Resources, Addis Ababa University. Then, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethiopian Public Health Institute Scientific and Ethical Review Board with reference number EPHI 613/138 in June 2019. To collect the data, written consent was obtained from each respondent after the objectives of this particular study were explained. Candidates were informed that their participation was voluntary. Confidentiality and privacy of respondents were ensured throughout the research process. The study design did not harm those taking part and it did not include any identifying information like name, or address of respondents.. They were well informed by the data collectors that the study was only for the purpose of academic and institutional research and not for any other business or illegal activities. Then, data were collected after assuring the confidential nature of responses.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the food handlers

A total of 1050 food handlers participated in the study with a response rate of 99.2%. In the current study, 77% of the participants were female. Of the total participants, 43.4% and 28.7% were between the age group of 18 to 22 and 23 to 27 years old respectively. The mean age of the respondents was 25.695 years. 82.7% of the food handlers had the ability to read and write, while 17.3% were illiterate. The majority of the participants (81.2%) were single. Of the total respondents, 73% of participants were Orthodox Christians and 13.1% were Muslims. Regarding work experience, 46.3% and 35.3% of the respondents had 1 to 5 years and <1 year of work experience as food handlers respectively. Furthermore, 17.8% of the food handlers had above 5 years of work experience as food handlers. The average length of food handlers work experience was found to be 3.34 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the food handlers (n = 1050).

| Study variables | Category | Frequency | Percent |

| Sex of the food handlers | Male | 242 | 23.0 |

| Female | 808 | 77.0 | |

| Age group of the food handlers | 18–22 years | 456 | 43.4 |

| 23–27 years | 301 | 28.7 | |

| 28–32 years | 127 | 12.1 | |

| >32 years | 166 | 15.8 | |

| Mean age of the food handles | 25.695 years with SD of ±7.576 | ||

| Minimum age of the food handlers | 18.00 years | ||

| Maximum age of the participants | 65.00 years | ||

| Educational status of the food handlers | Illiterate | 182 | 17.3 |

| At least read and write | 868 | 82.7 | |

| Marital status of the food handlers | Single | 853 | 81.2 |

| Married | 180 | 17.1 | |

| Divorced and others | 17 | 1.6 | |

| Religion of the food handlers | Orthodox | 766 | 73.0 |

| Muslim | 138 | 13.1 | |

| Others | 146 | 13.9 | |

| Work experience of the food handlers | <1 year | 371 | 35.3 |

| 1 to 5 years | 492 | 46.9 | |

| >5 years | 187 | 17.8 | |

| Mean work experience of the food handlers | 3.34 years with SD of ±3.37 years | ||

3.2. Food handlers work profile, medical checkup practice and training situation

The study found 45.1% and 44% of the food handlers' role was cooking and serving as waiters respectively. Of the total participants, 85% and 15% of the food handlers live and sleep in their home and at the food establishments respectively. More than half (57.4%) of the food handlers had no medical checkup or health examination certificate within the past three months prior to the study. From the total respondents, 61.3% of the food handlers reported that there was a mechanism of isolation for sick food handlers from the workplace. However, a greater number of food handlers (83.1%) had no training on food and water safety at least once in the past year prior to the study (Table 2).

Table 2. Food handlers work profile, medical checkup practice and training situation (n = 1050).

| Study variables | Category | Frequency | Percent |

| Role of food handlers in the food establishment | Cook | 474 | 45.1 |

| Waiter | 462 | 44.0 | |

| Both cooker and waiter | 114 | 10.9 | |

| Place of food handlers living and sleeping | At the food establishment | 158 | 15.0 |

| At her/his home | 892 | 85.0 | |

| Type of employee in the food establishment | Permanent | 177 | 16.9 |

| Temporary | 873 | 83.1 | |

| Medical checkup or health examination certificate at least within every three month | Yes | 447 | 42.6 |

| No | 603 | 57.4 | |

| Isolation of sick food handlers from the work place when food handler is ill | Yes | 644 | 61.3 |

| No | 406 | 38.7 | |

| Training of food handles on food and water safety at least once in a year | Yes | 177 | 16.9 |

| No | 873 | 83.1 |

3.3. Type of disease symptom and morbidity among the food handlers

Out of the 1,050 food handlers, 36 had diarrhea two weeks before the interview or a prevalence of 3.4%. Further, from the total participants, 17 (1.6%) of the food handlers had Acute Watery Diarrhea confirmed by a laboratory in the past year prior to this study. Moreover, 10.5%, 10.7% and 9% of the food handlers had a cough, infection or runny nose (influenza) and the incidence of fever within the past two weeks prior to this study respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Type of disease symptom and morbidity among the food handlers.

| Study variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Diarrheal diseases within the past two weeks prior to this study | Yes | 36 | 3.4 |

| No | 1014 | 96.6 | |

| Acute Watery Diarrhea (AWD) confirmed by laboratory for the past one year prior to this study | Yes | 17 | 1.6 |

| No | 1033 | 98.4 | |

| Cough within the past two weeks prior to this study | Yes | 110 | 10.5 |

| No | 940 | 89.5 | |

| An infection of runny nose within the past two weeks prior to this study | Yes | 112 | 10.7 |

| No | 938 | 89.3 | |

| Incidence of any fever within the past two weeks prior to this study | Yes | 95 | 9.0 |

| No | 955 | 91.0 |

3.4. Factors that may be contribute to diarrheal diseases among food handlers

Of the total participants, 94.5% and 93.8% washed their hands regularly after using the toilet and before meal respectively. However, 39% of the respondents used the toilet wearing protective clothes/gown. Additionally, 81.9% of the food handlers washed their hands immediately after handling raw foods. Further, 91.6% and 92% of the participants regularly closed their drinking water container to prevent contamination, and regularly washed their drinking water container and utensils with sanitizers and disinfectants. Almost all (96.7%) of the participants were washed glasses or the materials used for drinking water at every event. Also, 82.3% of the respondents put cooked foods separately from raw foods. Although 91.1% of the respondents did not use the same chopping block and knife during processing raw food and cooked food, 24.1% of the participants had habits of eating raw beef and raw vegetables. The food handlers reported that 89% of them ate a meal regularly in the food establishments. However, only 33.3% of the participants used proper waste disposal methods. Further, 62.5% of the respondents utilized unimproved or traditional toilets (Table 4).

Table 4. Factors that may be contribute to diarrheal diseases among the food handlers.

| Study variables | Category | Frequency | Percent |

| Regular hands washing after toilet used (defecation) | Yes | 992 | 94.5 |

| No | 58 | 5.5 | |

| Washing hands before meal regularly | Yes | 985 | 93.8 |

| No | 65 | 6.2 | |

| Used toilet while wearing protective clothes/gown | Yes | 409 | 39.0 |

| No | 641 | 61.0 | |

| Hand washing immediately after handling raw foods | Yes | 860 | 81.9 |

| No | 190 | 18.1 | |

| Take precaution/close drinking water container regularly | Yes | 962 | 91.6 |

| No | 88 | 8.4 | |

| Washing drinking water container and food service utensils with sanitizers and disinfectants regularly | Yes | 966 | 92.0 |

| No | 84 | 8.0 | |

| Washing glass or the material used for drink water every event with safe water | Yes | 1015 | 96.7 |

| No | 35 | 3.3 | |

| Put cooked foods separately from raw foods | Yes | 864 | 82.3 |

| No | 186 | 17.7 | |

| Habit of eating raw Beef and raw vegetables | Yes | 253 | 24.1 |

| No | 797 | 75.9 | |

| Used the same chopping block and knife during the time of processing raw food and cooked food | Yes | 93 | 8.9 |

| No | 957 | 91.1 | |

| Feed regularly in the food establishment | Yes | 935 | 89.0 |

| No | 115 | 11.0 | |

| Type of food establishment that the food handlers work | One and above one star Hotel | 86 | 8.2 |

| Non star Hotel | 69 | 6.6 | |

| Bar and restaurant | 194 | 18.5 | |

| Cafe and restaurant | 76 | 7.2 | |

| Restaurant | 424 | 40.4 | |

| Cafe and others | 201 | 19.1 | |

| Used proper waste disposal methods (pedal dust bin, septic tank) | Yes | 350 | 33.3 |

| No | 700 | 66.7 | |

| Type of toilet most of the time used by food handlers | Unimproved or traditional toilet | 656 | 62.5 |

| Improved or water flush toilet | 394 | 37.5 | |

| Presence of sanitary inspection by authorized bodies in the food establishment | Yes | 865 | 82.4 |

| No | 185 | 17.6 | |

| Type of the establishment in size the food handlers work | Small food establishment | 964 | 91.8 |

| Big food establishment | 86 | 8.2 |

3.5. Behavioral factors associated with diarrhea

In the binary logistic regression analysis, thirteen (13) explanatory variables like educational level of food handlers, regular hand washing after toilet used (defecation), regular hand washing before meal, used toilet with wearing protective clothes/gown, regular hand washing immediately after holding raw foods, closing drinking water container regularly, washing drinking water container with safe water and food service utensils with sanitizers and disinfectants, washing glass or the material used for drink water every event, separation of cooked foods from raw foods, habit of eaten raw beef and raw vegetables, used the same chopping block and knife during the time of processing raw food and cooked foods, type of toilet most of the time used by food handlers and presence of sanitary inspection by authorized bodies in the food establishment were significant associated (p-value < 0.028) with diarrheal disease in the past two weeks prior to this study. However, only five (5) predictor variables including: regular hand washing after toilet used (defecation), toilet use while wearing protective clothes/gown, washing glass or the material used for drink water every event, habit of eating raw beef and raw vegetables and type of toilet used by food handlers were appeared in the final condensed model of the multivariable analysis with P-value < 0.05 (Table 5).

Table 5. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of diarrheal disease with selected explanatory variables among the food handlers (n = 1050).

| Study variables | Diarrhea |

Β | Wald | P Value | AOR with 95%CI | ||

| Yes | No | ||||||

| Regular hand washing after toilet used or defecation | Yes | 9 | 983 | −2.029 | 5.496 | 0.019 | 0.13(0.024–0.72) |

| No | 27 | 31 | Reference | ||||

| Used toilet while wearing protective clothes/gown | Yes | 28 | 381 | 1.684 | 7.283 | 0.007 | 5.39(1.59–18.32) |

| No | 8 | 633 | Reference | ||||

| Washing glass or the material used for drink water every event with safe water | Yes | 11 | 1004 | −4.724 | 15.532 | 0.000 | 0.009(0.001–0.093) |

| No | 25 | 10 | Reference | ||||

| Habit of eating raw Beef and raw vegetables | Yes | 30 | 223 | 1.836 | 9.010 | 0.003 | 6.27(1.89–20.78) |

| No | 6 | 791 | Reference | ||||

| Improved or water flush Toilet used by food handler | Yes | 7 | 387 | 1.405 | 4.079 | 0.043 | Reference |

| No | 29 | 627 | 4.07(0.29–6.67) | ||||

4. Discussion

The aims of this study were to identify the prevalence of diarrheal disease and associated behavioral factors among food handlers. The self-reported prevalence of diarrheal disease in the two weeks before the interview was 3.4%.

This finding was lower than studies performed in Ethiopia and Haiti [22],[23]. This could be due to difference in attention given to health status and environmental risk factors. However, this result was consistent with a similar study conducted in Ireland [24]. This could be due to presence of good awareness among the food handlers towards diarrheal diseases. Further, this result was nearly consistent with a study conducted in South India where the prevalence of diarrhea among food handlers was 5.52% [25]. The slight difference might be due to the presents of recurrent food and water borne diseases in Addis Ababa and made alerted the food handlers about diarrheal diseases.

From the total participants, 17 (1.6%) of the food handlers had Acute Watery Diarrhea confirmed by laboratory testing in the past year prior to this study. Because we did not find information from literature on the prevalence of acute watery diarrhea among food handlers, this result needs further research because it is a major public health problem. Moreover, 10.5%, 10.7% and 9% of the food handlers had a cough, infection or runny nose (influenza) or the incidence of fever within the past two weeks prior to this study respectively. This indicates the health status of food handlers was poor though they were expected to be healthy and not transmit any infection to customers.

This study revealed that food handlers who had washed their hands after defecation or toilet use were 13% less likely to report diarrhea than those who did not report hand washing. This finding was supported by a study from low and middle income countries [26]. As expected, this may be due to removal of pathogenic organisms during proper hand washing after toilet use. Therefore, washing hands properly at the most recommended times is the key preventive mechanism of diarrheal disease. However, food handlers who used toilet while wearing protective clothes/gown had 5.39 times higher risk of diarrheal disease (AOR = 5.39 with 95% CI; 1.59, 18.32) relative to those who had not used the toilet while wearing personal protective device. This indicates personal protective equipment can carry pathogenic organisms or might be vehicles although no study reported this. Therefore, this needs future research to obtain additional information. Moreover, our finding revealed that food handlers who utilized washed glass or the material used for drinking water had prevented risk of diarrhea by 0.9% times higher (AOR = 0.009 with 95% CI: 0.001, 0.093) than those who did not. This indicates that, using safe water-washed glass reduces the risk of diarrheal disease. The odds of having diarrheal disease was 6.27 times higher among food handlers who had the habit of eating raw beef and raw vegetables (AOR = 6.27 with 95% CI: 1.89–20.78) than those who did not. This finding was supported by a 2017 study done in Bejing, China [21]. Further, the odds of having diarrheal disease was 4.07 times higher among those food handlers who used unimproved/traditional pit toilet (AOR = 4.07 with 95%CI: 0.29–6.67) than those who used improved or water flush toilet. Although in general the presence of a sanitary facility prevents different communicable diseases [26], this result shows using a traditional pit latrine had its own health impact on a community.

5. Conclusion

This study assessed the prevalence of diarrheal disease and identifies behavioral factors associated with diarrhea. This assessment proved to be an essential activity for reduction of community- acquired diarrheal diseases, as a significant number of food handlers had diarrhea. Good sanitation, hygiene practice and a healthy lifestyle behavior can prevent diarrhea. A strong political commitment with appropriate budgetary allocation is essential for the control of diarrheal diseases. The government should focus on a comprehensive diarrheal disease control strategy including improvement of water quality, hygiene, and sanitation. Current public health programs of the Addis Ababa city administration should develop effective approaches to promote hand washing practice and creation of awareness. Moreover, other interventions should be strengthened to reduce the occurrence of diarrhea. Improved interventions combined with formal training on food safety practice should be strengthened to reduce occurrence of diarrhea among the food handlers and to reduce health problems of their customers. Moreover, routine inspections should be conducted by authorized bodies to enhance hygiene and sanitation practices of food handlers.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Ethiopian Institute of Water Resources, Addis Ababa University for providing Financial Support. In addition, the authors like to express gratitude to the data collectors, supervisors and study participants.

Funding: Ethiopian Institute of Water Resources, Addis Ababa University was the funder to this study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish and interpretation of the data or preparation of the manuscript for publication.

Authors Contributions: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis ,Validation and Visualization, Writing-review & editing and approving: Aderajew Mekonnen, Sirak Robele, Bezatu Mengistie, Martin Evans, Azage Gebreyohannes.

Funding acquisition: Aderajew Mekonnen; Writing original draft: Aderajew Mekonnen

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflict of interest in this paper.

Reference

- 1.Dagnew AB, Tewabe T, Miskir Y, et al. Prevalence of diarrhea and associated factors among under-five children in Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:417. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4030-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007–2015. World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed T, Svennerholm A. Diarrheal disease: Solutions to defeat a global killer. Path Catal Glob Health. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bbaale E. Determinants of diarrhoea and acute respiratory infection among under-fives in Uganda. Australas Med J. 2011;4:400–407. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2011.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troeger C, Blacker BF, Khalil IA, et al. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1211–1228. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30362-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodge J, Chang HH, Boisson S. Assessing the Association between Thermotolerant Coliforms in Drinking Water and Diarrhea: An Analysis of Individual–Level Data from Multiple Studies. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1560–1567. doi: 10.1289/EHP156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams P, Berkley J. Severe acute malnutrition update: current WHO guidelines and the WHO essential medicine list for children. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaffee S, Henson S, Unnevehr L, et al. World Health Organization Global Estimates and Regional Comparisons of the Burden of Foodborne Disease. University of Southern California Los Angeles; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Havelaar AH, Kirk MD, Torgerson PR, et al. World Health Organization global estimates and regional comparisons of the burden of foodborne disease. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panchal PK, Bonhote P, Dworkin MS. Food safety knowledge among restaurant food handlers in Neuchatel, Switzerland. Food Prot Trends. 2013;33:133–144. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Advancing food safety initiatives: strategic plan for food safety including foodborne zoonoses 2013–2022. World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sumner S, Brown LG, Frick R, et al. Factors associated with food workers working while experiencing vomiting or diarrhea. J Food Prot. 2011;74:215–220. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waithaka PN, Maingi JM, Nyamache AK. Physico-chemical and microbiological analysis in treated, stored and drinking water in Nakuru North, Kenya. 2014.

- 14.Grace D. White paper Food safety in developing countries: research gaps and opportunities. Feed Future. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotloff KL. The burden and etiology of diarrheal illness in developing countries. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017;64:799–814. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ifeadike CO, Ironkwe OC, Adogu POU, et al. Prevalence and pattern of bacteria and intestinal parasites among food handlers in the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2012;53:166. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.104389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bain R, Cronk R, Hossain R, et al. Global assessment of exposure to faecal contamination through drinking water based on a systematic review. Trop Medi Int Health. 2014;19:917–927. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Mortality and burden of disease from water and sanitation. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data. 2014.

- 19.Girmay AM, Evans MR, Gari SR, et al. Urban health extension service utilization and associated factors in the community of Gullele sub-city administration, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2019;6:976–985. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berhanu M, Raghuvanshi TK, Suryabhagavan KV. Web-based GIS approach for tourism development in addis ababa city, Ethiopia. Malays J Remote Sens GIS. 2017;6:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma C, Wu S, Yang P, et al. Behavioural factors associated with diarrhea among adults over 18 years of age in Beijing, China. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:451. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abera B, Biadegelgen F, Bezabih B. Prevalence of Salmonella typhi and intestinal parasites among food handlers in Bahir Dar Town, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2010;24 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llanes R, Somarriba L, Velázquez B, et al. Low prevalence of Vibrio cholerae O1 versus moderate prevalence of intestinal parasites in food-handlers working with health care personnel in Haiti. Pathog Global Health. 2016;110:30–32. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2016.1141471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scallan E, Majowicz SE, Hall G, et al. Prevalence of diarrhoea in the community in Australia, Canada, Ireland, and the United States. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:454–460. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mt S, Murugan S, Pm N, et al. Evaluation of hygienic and morbidity status of food handlers at eating establishment in coimbatore district, South India–An Empirical Study. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci J. 2014;2:131–135. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Preventing diarrhoea through better water, sanitation and hygiene: exposures and impacts in low-and middle-income countries. World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]