Abstract

Although reovirus infections are thought to be common in adults, there have been few assessments of the seroprevalence of reovirus in young children. We developed an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to measure levels of total antireovirus immunoglobulin A, G, and M in serum specimens collected from otherwise healthy infants and children (1 month to 5 years of age) in Nashville, Tennessee. Of the 272 serum specimens evaluated, 64 (23.5%) tested positive for reovirus-specific antibodies. We observed an age-dependent increase in reovirus-specific antibodies in children 1 year of age and older, peaking at 50.0% in children 5–6 years of age. These findings suggest that reovirus infections are common during early childhood

Mammalian orthoreoviruses (here called “reoviruses”) are nonenveloped viruses comprising 2 icosahedrically symmetric protein capsids containing a genome of 10 functionally and structurally discrete segments of double-stranded RNA. Reoviruses commonly infect humans; however, most reovirus infections are thought to be asymptomatic [1]. Previous studies and case reports have linked reovirus infections with minor upper respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms or with central nervous system disease in children [2–4 ]. An association between reovirus infection and neonatal extrahepatic biliary atresia has been suggested [5] but remains to be proven. Since few seroepidemiologic studies of reovirus exist, we determined the titers of reovirus-specific antibodies in young children residing in Nashville, Tennessee, from 1989 to 2001

Subjects and methodsTwo hundred seventy-two serum specimens were obtained from the Vanderbilt Vaccine Clinic, a primary-care clinic established for the purpose of evaluating investigational vaccines in young children and conducting surveillance for enteric and respiratory viruses. Healthy full-term infants were enrolled at birth and were followed until 5 years of age, although specimens were occasionally collected from older subjects. Children who developed chronic diseases other than mild asthma were excluded. Well and ill visits were conducted within the Vanderbilt General Clinical Research Center, with care provided by the pediatric infectious diseases faculty and nurse practitioners. Appropriate informed consent for participation in the Vanderbilt Vaccine Clinic was obtained, and the reovirus study protocol, which used deidentified serum specimens, was approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board

Specimens used in the present study were collected from December 1989 to August 2001 and were chosen randomly to yield similar numbers of serum specimens per 1-year age group. Serum was obtained from peripheral blood by use of serum separator tubes and was stored at −20°C until testing. For the purposes of the present study, each serum specimen was collected from a unique patient. One hundred thirty-nine specimens (51.1%) were collected from males. The age distribution of the children from whom the 272 serum specimens were collected was as follows: 8 children (2.9%) were between 1 and 3 months of age, 9 (3.3%) were between 3.1 and 6 months of age, 17 (6.3%) were between 6.1 and 9 months of age, 8 (2.9%) were between 9.1 and 12 months of age, 49 (18.0%) were between 1 and 2 years of age, 48 (17.6%) were between 2 and 3 years of age, 53 (19.5%) were between 3 and 4 years of age, 58 (21.3%) were between 4 and 5 years of age, and 22 (8.1%) were between 5 and 6 years of age. The dates of collection were distributed as follows: 4 specimens (1.5%) were collected in 1989, 77 specimens (28.3%) in 1990, 26 specimens (9.6%) in 1991, 29 specimens (10.7%) in 1992, 39 specimens (14.3%) in 1993, 29 specimens (10.7%) in 1994, 25 specimens (9.2%) in 1995, 16 specimens (5.9%) in 1996, 5 specimens (1.8%) in 1997, 10 specimens (3.7%) in 1998, 5 specimens (1.8%) in 1999, 3 specimens (1.1%) in 2000, and 4 specimens (1.5%) in 2001

An indirect ELISA was developed to detect the level of total IgA, IgG, and IgM against prototype reovirus strain type 3 Dearing (T3D) in serum specimens. T3D virion particles were purified from lysates of infected mouse L929 cell-suspension cultures by cesium-chloride density gradient centrifugation, as described elsewhere [6]. Mock-infected lysate prepared in the same manner was used as a control. The optimal viral antigen concentration for detection of reovirus-specific antibodies was determined by use of parallel assays. Rabbit polyclonal serum raised against α-catenin or coronavirus p12 or p22 was used as a negative control. Composition of blocking buffers, secondary antibody concentrations, and development times were optimized to maximize assay signal. All assays were performed with a single preparation of viral particles or mock-infected lysate, which were diluted in 0.05 mol/L carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) immediately before use

Wells of 96-well Immulon 2 HB plates (Thermo Labsystems) were coated with 2 μg (equivalent to 2.3×1010 particles) of purified virus or an equivalent volume of mock-infected lysate or were left uncoated overnight at 4°C. Plates were subsequently incubated with 200 μL of blocking buffer (PBS, 5% dried nonfat milk, and 0.05% Tween 20) overnight at 4°C and were washed. Serum specimens were serially diluted 2-fold in blocking buffer, from 1:160 to 1:1280, and incubated with virus-coated wells for 2 h at room temperature. Serum specimens also were tested against mock-infected lysate–coated wells, at dilutions of 1:160 and 1:640, and against uncoated wells, at a dilution of 1:40. Specimens with high titers were additionally tested, at dilutions of 1:2560, 1:5120, and 1:10,240, for binding to virus-coated or mock-infected lysate–coated wells, to determine end-point titer. Each assay included a high-titer adult specimen as a positive control

After incubation, plates were washed (EL 403H; Biotek Instruments) 4 times with PBS-T (PBS and 0.02% Tween 20), and wells were incubated with 100 μL of horseradish-peroxidase–conjugated goat antibodies to total human IgA, IgG, and IgM (Southern Biotechnology) diluted 1:4000 in blocking buffer. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, plates were washed 4 times with PBS-T. One hundred microliters of 0.05 mol/L phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 0.18 mmol/L 2,2′-azino-bis-3-ethylbenz-thiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (Sigma) and 0.0075% H2O2 was added to each well. Color was developed for 30 min at room temperature, after which 100 μL of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate was added, to terminate the reaction. Optical density was measured at 405 nm (SPECTRAmax PLUS384; Molecular Devices)

A serum specimen was designated as positive if the ratio of signal for virus-coated to mock-infected lysate–coated wells was ⩾2 at a dilution ⩾1:160. The antibody titer assigned to a given specimen was the highest dilution that yielded a positive result. Fisher’s t test was used to evaluate differences in seroprevalence among age groups and differences in prevalence of antireovirus and antilysate antibodies. Analysis of variance was used to compare geometric mean titers (GMTs). P<.05 was considered to be statistically significant

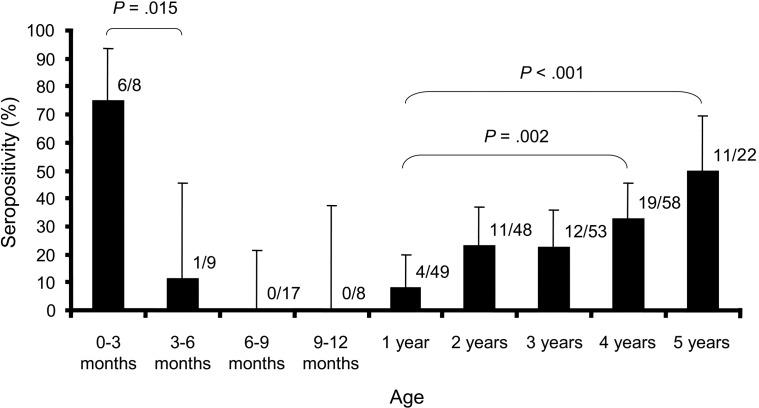

ResultsOf the 272 serum specimens evaluated in the present study, 64 (23.5%) were found to be positive for reovirus-specific antibodies (figure 1). Thirty-five (25.2%) of 139 from males and 29 (21.8%) of 133 from females were found to be seropositive (P=.512). Rapid loss of maternal antibody was demonstrated by the decrease of seroprevalence from 75.0% in infants 0–3 months of age to 11.1% in those 3–6 months of age (P=.015). Seroprevalence decreased to 0% in children 6–12 months of age and then increased steadily throughout early childhood. In contrast to children 1–2 years of age, who had a seroprevalence of 8.2%, 32.8% of children 4–5 years of age (P=.002) and 50.0% of children 5–6 years of age (P<.001) were found to be positive for antireovirus antibodies

Figure 1.

Prevalence of reovirus-specific antibodies by age group. Two-hundred seventy-two serum specimens collected from young children were analyzed, by indirect ELISA, for the presence of total IgA, IgG, and IgM specific for type 3 reovirus. The no. of positive specimens and the total no. of specimens for each age group are shown. The error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for each age group. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine statistical significance of associations

To determine the extent to which antimouse antibodies in serum specimens may have caused false-positive results, all specimens were tested against lysates prepared from mock-infected mouse L929 cells. Twenty-eight (10.3%) of the 272 specimens were found to be positive for antimouse antibodies (26 with a titer of 1:160 and 2 with a titer of 1:640); of these, all but 6 were found to be negative for reovirus-specific antibodies. Of the 244 specimens found to be negative for antimouse antibodies, 186 were found to be negative for reovirus-specific antibodies. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of antimouse antibodies among reovirus-seropositive and -seronegative specimens (P=.82), suggesting that cross-reactivity between murine and reovirus antigens did not confound the results

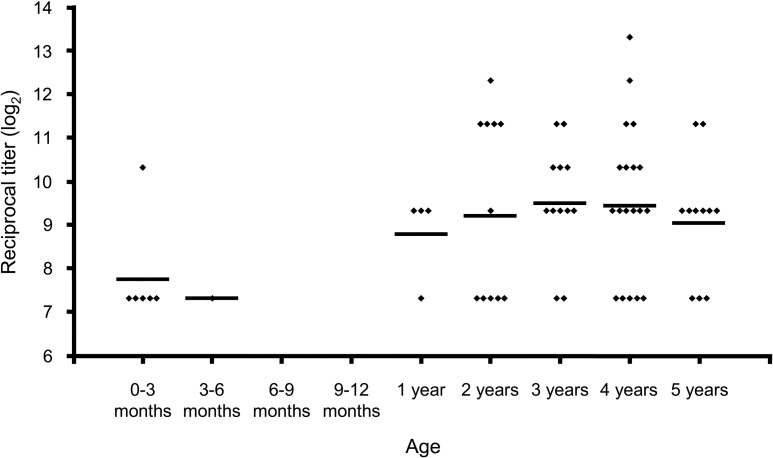

In the 64 serum specimens found to be positive, antibody titers ranged from 1:160 to 1:10,240 (figure 2). Forty-three (67.2%) of the 64 serum specimens found to be positive had titers of either 1:160 or 1:640. There were no significant differences in GMTs for all age groups

Figure 2.

Titers of reovirus-specific antibodies in seropositive subjects, by age group. End-point titer was determined for 64 serum specimens that tested positive for reovirus-specific antibodies by indirect ELISA. Each diamond represents the log2 reciprocal titer for an individual sample obtained from a unique study participant. The horizontal line for each age group designates the geometric mean titer (GMT) for that group. GMTs are as follows: 1:215 for 0–3 months of age, 1:160 for 3–6 months of age, 1:438 for 1–2 years of age, 1:586 for 2–3 years of age, 1:718 for 3–4 years of age, 1:691 for 4–5 years of age, and 1:527 for 5–6 years of age

Seropositivity and GMTs did not vary significantly between specimens from the different collection periods. Twenty-four (22.4%) of the 107 specimens collected during 1989–1991 were found to be positive, as were 21 (21.6%) of the 97 specimens collected during 1992–1994, 14 (30.4%) of the 46 specimens collected during 1995–1997, and 5 (22.7%) of the 22 specimens collected during 1998–2001. GMTs for these collection periods were, respectively, 1:453, 1:508, 1:999, and 1:1114

DiscussionMammalian reoviruses are common infectious agents in humans. Determining the prevalence of reovirus-specific antibodies can help to elucidate proposed but unproven associations between reovirus infection and clinical disease, such as neonatal extrahepatic biliary atresia or meningitis. The present study investigated the seroepidemiology of type 3 reovirus infection in young children residing in the Nashville metropolitan area

There have been few reported studies of reovirus seroepidemiology to date. The last study in the United States was published in 1962 [7] and showed that prevalence of reovirus-specific antibodies decreased with the loss of passive immunity to <10% in children 7–12 months of age and then increased gradually to >60% in persons >60 years of age. The present study examined a narrower range of ages and a greater number of specimens, all of which were collected from pediatric patients. A more recent study in Germany yielded similar results, with a nadir seroprevalence of 24% among children 2–3 years of age and an age-dependent increase of seroprevalence of type 3 reovirus IgG [8]. Children 5–6 years of age had a seroprevalence of >40%

In the present study, patterns of prevalence of antibodies specific for type 3 reovirus were consistent with maternal-fetal antibody transmission, with the lowest prevalence between 6 and 12 months of age. We observed a steady increase in seroprevalence throughout early childhood that likely represents the response to natural infection, with half of the children 5–6 years of age found to be positive for reovirus-specific antibodies, a result consistent with the findings of previous studies. Age-group differences in GMTs of seropositive specimens did not reach statistical significance. There were no significant differences in either prevalence or GMTs of seropositive specimens from the different collection periods over the course of the 11-year total collection period

Taking these data into account, we think it is likely that most reovirus infections either are asymptomatic or result in mild upper respiratory infection or gastroenteritis [2, 3] that often goes undocumented. In this respect, reovirus would be similar to other viruses, such as hepatitis GB virus [9] and TT virus [10], which are not known to cause symptomatic infection. A certain small proportion of those infected, however, may develop severe clinical disease, including neonatal extrahepatic biliary atresia or meningitis [4, 5]. Since reoviruses display age-dependent virulence in experimental animals [11, 12], these severe manifestations would be anticipated to occur only in the very young. Thus, the low frequency with which reovirus disease is observed may be explained by the relatively high rate of lingering passive immunity in this population

In comparison with other methods of detecting reovirus-specific antibodies in serum, ELISA requires little labor or time. Other advantages are its low cost and use of small amounts of serum. Prior studies have shown ELISA to have limited serotype specificity with regard to reovirus: there is significant cross-reactivity between all 3 reovirus serotypes [13, 14]. This observation suggests that our assay was capable of detecting antibodies against reovirus serotypes other than type 3, although only antibodies directed against type 3 reovirus were specifically measured in the present study

Among the limitations of the present study are the narrow geographical distribution of the study subjects and the relatively low numbers of specimens. Another potential limitation is the long collection period, although there does not appear to have been a significant shift in seroprevalence during the collection period. However, a potential advantage of the approach used here is the avoidance of variability introduced by seasonality

The findings of the present study suggest that antibody responses to reovirus are acquired during early childhood. Topics of future research include the association between clinical symptoms and reovirus seroconversion in this cohort and possible disparities in patterns of seroprevalence of reovirus between different geographical regions

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Frances House, for invaluable assistance with clinical samples used in the present study; Yuwei Zhu, for statistical support; and Lisa Rush, for database support. We are also grateful to James Chappell and Timothy Peters, for helpful comments, and Denise Wetzel, for assistance with laboratory studies

Footnotes

Presented in part: Eighth Southeastern Regional Virology Conference, Atlanta, Georgia, 27 March 2004

Financial support: National Institutes of Health (Public Health Service awards R01 AI38296, N01 AI05050, N01 AI64298, and M01 RR00095); Elizabeth B. Lamb Center for Pediatric Research

References

- 1.Tyler KL. Mammalian reoviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, et al., editors. Fields virology. 4th ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 1729–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson GG, Muldoon RL, Cooper RS. Reovirus type 1 as an etiologic agent of the common cold. J Clin Invest. 1961;40:1051. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen L, Evans HE, Spickard A. Reovirus infections in human volunteers. Am J Hyg. 1963;77:29–37. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyler KL, Barton ES, Ibach ML, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of a novel type 3 reovirus from a child with meningitis. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1664–75. doi: 10.1086/383129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tyler KL, Sokol RJ, Oberhaus SM, et al. Detection of reovirus RNA in hepatobiliary tissues from patients with extrahepatic biliary atresia and choledochal cysts. Hepatology. 1998;27:1475–82. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furlong DB, Nibert ML, Fields BN. Sigma 1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J Virol. 1988;62:246–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.246-256.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerner AM, Cherry JD, Klein JO, Finland M. Infections with reoviruses. N Engl J Med. 1962;267:947–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196211082671901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selb B, Weber B. A study of human reovirus IgG and IgA antibodies by ELISA and Western blot. J Virol Methods. 1994;47:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alter HJ, Nakatsuji Y, Melpolder J, et al. The incidence of transfusion‐associated hepatitis G virus infection and its relation to liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:747–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703133361102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leary TP, Erker JC, Chalmers ML, Desai SM, Mushahwar IK. Improved detection systems for TT virus reveal high prevalence in humans, non‐human primates and farm animals. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2115–20. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-8-2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tardieu M, Powers ML, Weiner HL. Age‐dependent susceptibility to reovirus type 3 encephalitis: role of viral and host factors. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:602–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann MA, Knipe DM, Fischbach GD, Fields BN. Type 3 reovirus neuroinvasion after intramuscular inoculation: direct invasion of nerve terminals and age‐dependent pathogenesis. Virology. 2002;303:222–31. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson SC, Bishop RF, Smith AL. Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays for measurement of reovirus immunoglobulin G, A, and M levels in serum. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1871–3. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1871-1873.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spijkers H, Broeders H, Groen J, Osterhau A. Comparison of enzyme‐linked immunosorbent and virus neutralization assays for the serology of reovirus infections in laboratory animals. Lab Anim Sci. 1990;40:150–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]