Abstract

Background. The lectin DC-SIGN (dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin) augments Ebola virus (EBOV) infection. However, it its unclear whether DC-SIGN promotes only EBOV attachment (attachment factor function, nonessential) or actively facilitates EBOV entry (receptor function, essential).

Methods. We investigated whether DC-SIGN on B cell lines and dendritic cells acts as an EBOV attachment factor or receptor.

Results. Engineered DC-SIGN expression rendered some B cell lines susceptible to EBOV glycoprotein (EBOV GP)-driven infection, whereas others remained refractory, suggesting that cellular factors other than DC-SIGN are also required for susceptibility to EBOV infection. Augmentation of entry was independent of efficient DCSIGN internalization and might not involve lectin-mediated endocytic uptake of virions. Therefore, DC-SIGN is unlikely to function as an EBOV receptor on B cell lines; instead, it might concentrate virions onto cells, thereby allowing entry into cell lines expressing low levels of endogenous receptor(s). Indeed, artificial concentration of virions onto cells mirrored DC-SIGN expression, confirming that optimization of viral attachment is sufficient for EBOV GP-driven entry into some B cell lines. Finally, EBOV infection of dendritic cells was only partially dependent on mannose-specific lectins, such as DC-SIGN, suggesting an important contribution of other factors.

Conclusions. Our results indicate that DC-SIGN is not an EBOV receptor but, rather, is an attachmentpromoting factor that boosts entry into B cell lines susceptible to low levels of EBOV GP-mediated infection.

The filoviruses Ebola virus (EBOV) and Marburg virus (MARV) are negative-strand nonsegmented RNA viruses that cause hemorrhagic fever in humans [1]. Filoviruses display an extremely broad tropism, infecting virtually all cell types, except lymphoid cells [2–4]. The cellular receptors for filoviruses are not well defined, although a role for Tyro-3 kinases has recently been proposed [5]. Binding of the viral glycoproteins (GPs) to cellular lectins can augment filovirus attachment and subsequent infectious entry into target cells [6], suggesting that lectin engagement might modulate filovirus tropism.

Several lines of evidence indicate that the calciumdependent (C-type) lectins DC-SIGN (dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin)/CD209 and the related protein DCSIGNR/L-SIGN/CD209L (collectively referred to as “DC-SIGN/R”), which recognize high-mannose carbohydrates on the EBOV GP [7, 8], might impact the spread of filovirus infection. First, engineered expression of DCSIGN/R augments filovirus GP-dependent entry [9–12]. Second, DC-SIGN/R are endogenously expressed on important target cells of EBOV infection, including mononuclear cells expressing markers of dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages (DC-SIGN) [13, 14] and endothelial cells in the liver and lymph node sinusoids (DC-SIGNR) [15, 16]. Third, DC-SIGN-positive cells with dendritic morphology were shown to be infected in EBOV-inoculated macaques [2].

The precise role of DC-SIGN/R in filovirus entry is unclear. The observation that DC-SIGN/R expression allows efficient EBOV-GP-dependent infection of certain lymphoid cell lines [9] raises 2 possibilities concerning DC-SIGN/R function. DCSIGN/R might act as attachment factors [17] that concentrate filoviruses onto cells and thereby promote subsequent engagement of as-yet-unknown receptor(s), a mechanism that would be particularly relevant when receptor expression levels limit infection efficiency. In such a scenario, DC-SIGN/R would augment filovirus infection; nevertheless, under conditions of artificially optimized viral attachment, these factors would be dispensable for infectious entry. Alternatively, these lectins might function as filovirus receptors [17], which actively promote cellular entry of filoviruses into cells that, even under conditions of optimal viral attachment, are otherwise nonsusceptible. In the latter case, DC-SIGN/R should mediate internalization of virions into endosomal compartments, where the fusion activity of GP is activated by cathepsin cleavage, a prerequisite to infectious EBOV entry [18].

To determine the contribution of DC-SIGN/R to EBOV infectious entry, we analyzed whether engineered DC-SIGN/R expression is necessary and sufficient to mediate entry of EBOV GP-pseudotyped reporter viruses (pseudotypes) into different B cell lines. Similarly, we asked whether DC-SIGN engagement is essential for EBOV infection of DCs. Moreover, we investigated whether DC-SIGN/R internalization after ligand binding is required for augmentation of infectivity. We report that DC-SIGN/R can mediate EBOV GP-driven infection of certain B cell lines. However, DC-SIGN/R-promoted entry was cell line dependent, and DC-SIGN/R function could be substituted by artificial concentration of virions onto cells. DC-SIGN engagement was also not essential for infection of DCs with EBOV. Finally, DC-SIGN/R-dependent augmentation of EBOV GP- driven entry did not require intact internalization-mediating sequence motifs (i.e., internalization motifs) in the DC-SIGN/ R cytoplasmic tails. These observations argue against an active role for DC-SIGN/R in EBOV entry, and they suggest that factors other than DC-SIGN/R are critical for infectious entry to occur. Cumulatively, our results indicate that DC-SIGN/R function as EBOV attachment-promoting factors and not entry receptors.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and cell lines. DC-SIGN/R variants with mutated LL and YXXL motifs were generated by overlap-extension polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based mutagenesis, by use of the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Invitrogen). The following primer pairs were used to mutate DC-SIGN: p5DCSmutYL (GATTCCGACAGACTCGAGGCGCCAAGAGCGGCGCAGGGTGTCTTGGCCAT) and p3DCSmutYL (ATGGCCAAGACACCCTGCGCCGCTCTTGGCGCCTCGAGTCTGTCGGAATC) (YXXL to AXXG), as well as p5DCSmutLL (AAGACTGCACAGCTGGGCGCCGCGGAGGAGGAACAGCTGAGAGGCCTTG) and p3DCSmutLL (CAAGGCCTCTCAGCTGTTCCTCCTCCGCGGCAGCCCAGCTGCTGCAGTCTT) (LL to AA). The LL to AA mutation in DC-SIGNR was introduced with primers p5DCSRmutLL (AAGGGTGCAGCAGCTGGGCGCCGCGGAAGAAGATCCAAC) and p3DCSRmutLL (GTTGGATCTTCTTCCGCGGCGCCCAGCTGCTGCACCCTT). The sequences of all DC-SIGN/R variants were confirmed by sequence analysis.

DC-SIGN/R expression vectors were transfected into 293 cells, and stable expressors were selected and enriched by fluorescence- activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. B-THP cells expressing exogenous DC-SIGNR were generated using lentivirus transduction as described elsewhere [11]. B-THP cells expressing DC-SIGN or D20 DC-SIGN have been described elsewhere [19]. In addition, monocyte-derived DCs (MDDCs) were generated as described elsewhere [20]. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)- transformed B lymphoblastoid cell lines were established by coincubation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with cellfree supernatant derived from the EBV-producing cell line B95-8 [21] in the presence of cyclosporine (100 ng/mL). All nonadherent cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (PAA), except Ramos B cells, which were propagated in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; Gibco/BRL). 293T cells and lectin-expressing 293 cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; PAA). All cell culture media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin.

Reporter viruses. For pseudotype production, 293T cells were cotransfected with equal amounts of EBOV GP expression plasmids and pNL4-3-Luc-R−E− [22], as documented elsewhere [11]. Production of replication-competent HIV-1 NL4-3 reporter virus bearing the luciferase gene in place of nef has been described elsewhere [23]. All cell culture supernatants were harvested 48 h after transfection, passed through filters with a pore size of 0.4 µm, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. To quantify virus production, the capsid protein content in cellular supernatants was determined by means of ELISA (Abbott Diagnostics). The relative infectivity of virus stocks was assessed by infection of 293T cells and quantification of luciferase activities in cellular lysates by use of a commercially available kit (Promega).

DC-SIGN/R expression and internalization. FACSanalysis was used to investigate cell surface expression of DC-SIGN/R and was generally performed using cells seeded in parallel for infection experiments. For conventional FACS analysis, DCSIGN/R expression was detected with DCN46 (BD Bioscience) or 507 (R&D Systems) antibody and an indodicarbocyanine (Cy5)-conjugated secondary antibody (Dianova). For quantitative FACS analysis of DC-SIGN/R expression, the anti-DCSIGN/R antibody DC 11 [24] and a commercially available kit (Sigma) were used as described in detail elsewhere [23, 25]. For analysis of DC-SIGN internalization, DC-SIGN-expressing cells were stained with antibodies 507 or DCN46 at 4°C, washed, and either maintained on ice or shifted to 37°C for the indicated times. Subsequently, secondary antibody was added and staining analyzed using FACS analysis.

Infection experiments. For infection experiments, B cell lines were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 3×104 cells/well and were incubated with infectivity-normalized viral supernatants. For spinoculation, virus-exposed cells were centrifuged for 1 h at 25°C at 270 g as described elsewhere [26]. For inhibition of DC-SIGN function, cells were incubated with the indicated antibodies at a final concentration of 10 µg/mL for 30 min at 37°C before infection. The medium was replaced 12 h after infection, and luciferase activities in cell lysates were determined 72 h after infection. HIV-1 transmission was analyzed as described elsewhere [23]. Zaire ebolavirus (ZEBOV) Mayinga was produced in Vero E6 cells, under biosafety level 4 conditions, as described elsewhere [27]. MDDCs were seeded on coverslips and pretreated with mannan at a final concentration of 100 µg/mL. ZEBOV infection and IFAs were performed as described elsewhere [12].

Results

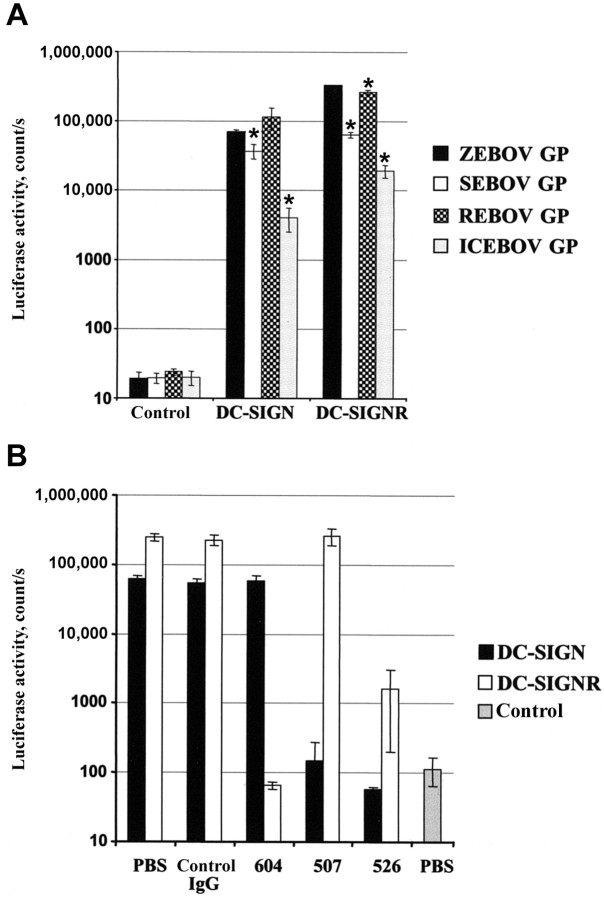

Robust EBOV GP-dependent entry into B-THP cells after DCSIGN/R expression. We first investigated whether expression of DC-SIGN/R allows EBOV GP-mediated infection of otherwise nonsusceptible cells. We chose B-THP cells [28], which are derived from the Raji B cell line, for these experiments, because B cell lines have been shown to be refractory to EBOV GP-driven infection [3]. Indeed, incubation of parental B-THP control cells with infectivity-normalized pseudotypes bearing the GPs of the 4 EBOV subspecies—ZEBOV, Sudan EBOV (SEBOV), Ivory Coast EBOV (ICEBOV), and Reston EBOV (REBOV)—did not result in signals above background levels (figure 1A). Thus, luciferase activities of 10–100 counts/s are usually measured after mock infection or infection with GPdeficient control viruses, and they are therefore considered to be unspecific [12, 29] (A.M. and S.P., unpublished data). In contrast, all GPs mediated robust infection of B-THP cells ex pressing exogenous DC-SIGN/R (figure 1A). ZEBOV GP and REBOV GP engaged DC-SIGN/R with higher efficiency than did SEBOV GP and, in particular, ICEBOV GP, as has been reported elsewhere [8, 29] for susceptible cells. Antibody inhibition experiments demonstrated that EBOV GP-mediated entry into B-THP cells expressing DC-SIGN/R was indeed dependent on GP interactions with these lectins (figure 1B). Thus, the DC-SIGNR-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) 604 strongly reduced entry into B-THP DC-SIGNR-expressing cells, but it had no effect on entry into B-THP DC-SIGN cells. The reverse observation was made with MAb 507, which is DCSIGN specific (figure 1B). Finally, MAb 526, which is dual specific, blocked EBOV GP-driven entry into both B-THP DCSIGN and DC-SIGNR cells, confirming that EBOV GP engages DC-SIGN/R for entry into B-THP cells. These results indicate that exogenous DC-SIGN/R can allow EBOV GP-mediated infection of B-THP cells.

Figure 1.

DC-SIGN/R (calcium-dependent [C-type] lectins DC-SIGN [dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing non-integrin]/CD209 and its homologue, DC-SIGNR/L-SIGN/CD209L, taken collectively) promote Ebola virus (EBOV) glycoprotein (GP)-driven entry into B-THP cells. A, DC-SIGN/R augment infection of B-THP cells with reporter viruses bearing the GPs of the 4 subspecies of EBOV. B-THP cell lines stably expressing DC-SIGN/R were infected with infectivity-normalized reporter viruses bearing the indicated EBOV GPs. Three days after infection, luciferase activities in cellular lysates were determined. A representative experiment is shown. Error bars denote SDs. A t test (2-tailed) for independent samples was used for statistical analysis. Asterisks denote values significantly different from those measured after Zaire EBOV (ZEBOV) GP-driven infection of cells expressing DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR, respectively (*P ⩽ .001). B, EBOV GP-mediated infection of B-THP DCSIGN/R cell lines is lectin dependent. B-THP cell lines were infected with ZEBOV GP-bearing reporter virus, and infection efficiency was quantified as described above. However, before infection, the cells were incubated with the indicated antibodies (10 µg/mL). Monoclonal antibody (MAb) 604 is specific for DC-SIGNR, MAb 507 binds DC-SIGN, and MAb 526 recognizes both lectins [25]. A representative experiment is shown. Error bars denote SDs. ICEBOV, Ivory Coast EBOV; REBOV, Reston EBOV; SEBOV, Sudan EBOV.

Enhancement of EBOV GP-mediated infection by DCSIGN/ R variants with mutated LL and YXXL motifs. The cytoplasmic tail of DC-SIGN harbors an LL motif and a YXXL motif, whereas only the former sequence is present in DCSIGNR (figure 2A). Both motifs constitute putative internalization signals and might promote EBOV transport into endosomes, a prerequisite for productive EBOV infection [18]. We analyzed the relevance of these motifs for DC-SIGN/R- mediated augmentation of EBOV GP-dependent infection. To this end, the LL motifs in DC-SIGN/R and the YXXL sequence in DC-SIGN were mutated (variants AA and AXXG) (figure 2A), or the entire cytoplasmic tails of DC-SIGN/R were deleted (variants DN-ter) (figure 2A). The lectin variants were stably expressed in kidney-derived 293 cells, which are highly permissive to EBOV GP-mediated entry [3].

Figure 2.

The cytoplasmic tails of DC-SIGN/R (calcium-dependent [C-type] lectins DC-SIGN [dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin]/CD209 and its homologue, DC-SIGNR/L-SIGN/CD209L, taken collectively) are not essential for augmentation of Zaire Ebola virus (ZEBOV) glycoprotein (GP)-driven infection. A, Schematic representation of the DC-SIGN/R variants analyzed. LL and YKSLs motifs in the DCSIGN/R cytoplasmic tails are highlighted. The sequences of the DC-SIGN/R ΔN-ter variants start at aa 38 and 48, respectively. B, Expression of DCSIGN/R variants (top) and augmentation of Ebola virus (EBOV) GP-driven infection (bottom). The nos. of copies of the indicated DC-SIGN (black bars) and DC-SIGNR (white bars) variants expressed on stably transfected 293 cell lines were determined by means of quantitative fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses performed as described elsewhere [25]. Expression of the DC-SIGN/R variants is shown relative to expression of the DCSIGN wild type (wt) (189,000 copies), which was set as 100%. The results denote the mean values from 5 independent experiments. Error bars denote SEMs. For analysis of DC-SIGN/R-mediated augmentation of EBOV GP-driven infection, the indicated cell lines were seeded in 96-well plates and infected with 10 ng of ZEBOV GP-bearing reporter virus/well, and luciferase activities in cellular lysates were determined. ZEBOV GP-driven infection of lectin-expressing cells is shown relative to infection of control cells, which was set as 100%. A representative experiment is shown; error bars denote SDs. A t test (2-tailed) for independent samples was used for statistical analysis. Asterisks denote values significantly different from those measured for DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR expression, respectively (top), or significantly different from those measured for infection of DC-SIGN- and DCSIGNR-expressing cells, respectively (bottom) (*P ⩽ .05; ** P ⩽ .001). TM, transmembrane domain; N-ter, N terminus.

Analysis of lectin expression by use of a quantitative FACS technique revealed that the mutation of the YXXL motif in DCSIGN moderately reduced expression, compared with the wildtype (wt) protein (figure 2B, top). Alteration of the LL motif in DC-SIGN slightly decreased, and the analogous change in DC-SIGNR slightly increased lectin expression levels, but both effects were not statistically significant. Double mutation of the LL and YXXL motifs in DC-SIGN diminished expression to ∼50%, compared with wt DC-SIGN, whereas deletion of the entire DC-SIGN cytoplasmic domain resulted in 80% reduction in expression (figure 2B, top). DC-SIGN/R variants with mutations in the cytoplasmic tails augmented EBOV GP—driven infection (figure 2B, bottom). However, enhancement of EBOV GP—mediated infectious entry clearly correlated with lectin expression levels (figure 2B, top and bottom). A strict correlation between DC-SIGN expression levels and augmentation of EBOV GP—dependent infection has been documented elsewhere [11], indicating that the effects observed after mutation of the YXXL and LL motifs were merely the result of limited DC-SIGN/R expression and not due to specific defects induced by these alterations. Thus, internalization motifs in DC-SIGN/R are not essential for functional interaction with EBOV GP— bearing pseudotypes, at least in the context of readily susceptible cells.

Augmentation of EBOV GP-dependent entry into B-THP cells by a SC-SIGN variant lacking the first 20 amino acids of the cytoplasmic tail. We next investigated whether the LL motif in DC-SIGN and its surrounding sequences are dispensable for EBOV GP-driven infectious entry into B-THP cells. To this end, B-THP cells expressing a DC-SIGN variant lacking the N-terminal 20 amino acids [19], which encompass the LL motif (Δ20) (figure 2A), were analyzed for lectin expression and enhancement of EBOV GP-dependent entry. Parental BTHP cells, B-THP DC-SIGN cells, and B-THP DC-SIGN cells sorted for high levels of DC-SIGN expression (hiDC-SIGN) were used as controls. FACS analyses revealed that B-THP Δ20 DC-SIGN cells expressed less lectin molecules on the surface than did B-THP DC-SIGN cells, whereas the highest levels of lectin expression were detected on B-THP hiDC-SIGN cells (figure 3A). All lectin-expressing cell lines were readily infected by EBOV GP pseudotypes, although infection efficiency was dependent on the efficiency of lectin expression, with B-THP hiDC-SIGN cells being most susceptible and B-THP Δ20 DCSIGN cells being least susceptible (figure 3A and 3B). Analyses of lectin internalization triggered by an antibody directed against the DC-SIGN lectin domain (507) or a control antibody (DCN 46) demonstrated less-efficient internalization of the Δ20 DC-SIGN variant relative to the wt protein (figure 3C), as reported elsewhere [30–33]. Thus, the N-terminal 20 amino acids of DC-SIGN are required for efficient lectin internalization after ligand binding but are not essential for DC-SIGN- mediated augmentation of EBOV GP-driven infection.

Figure 3.

The first 20 amino acids of the DC-SIGN (dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin) cytoplasmic tail are dispensable for augmentation of Ebola virus (EBOV) glycoprotein (GP)-dependent infection. A, DC-SIGN surface expression. Surface expression of DC-SIGN and DC-SIGN variant Δ20 on B-THP cells was analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. B, Enhancement of EBOV GP-dependent entry. The indicated B-THP cell lines were inoculated with ZEBOV GP-bearing reporter viruses, and luciferase activities in cellular lysates were determined. Data are shown relative to infection of B-THP control cells and denote the mean values (±SEMs) from 3 independent experiments. A t test (2-tailed) for independent samples was used for statistical analysis. Asterisks denote values significantly different from those measured after infection of hiDC-SIGN cells (*P ⩽ .05). C, DC-SIGN internalization. B-THP cells expressing DC-SIGN and DC-SIGN variant Δ20 were incubated with anti-DC-SIGN antibodies 507 (specific for the lectin domain) and DCN 46 (specific for the neck domain) at 4°C and were shifted to 37°C for the indicated times, followed by analysis of lectin expression by FACS. Geometric mean channel fluorescence of cells maintained at 4°C during the entire experiment was set as 100%. Data denote the mean values (±SEMs) from 3 independent experiments. A t test (2-tailed) for dependent samples was used for statistical analysis. Asterisks denote values significantly different from those measured for DC-SIGN and variant ±20 at 0 min (*P ⩽ .05). hiDC-SIGN, cells sorted for high levels of DC-SIGN expression.

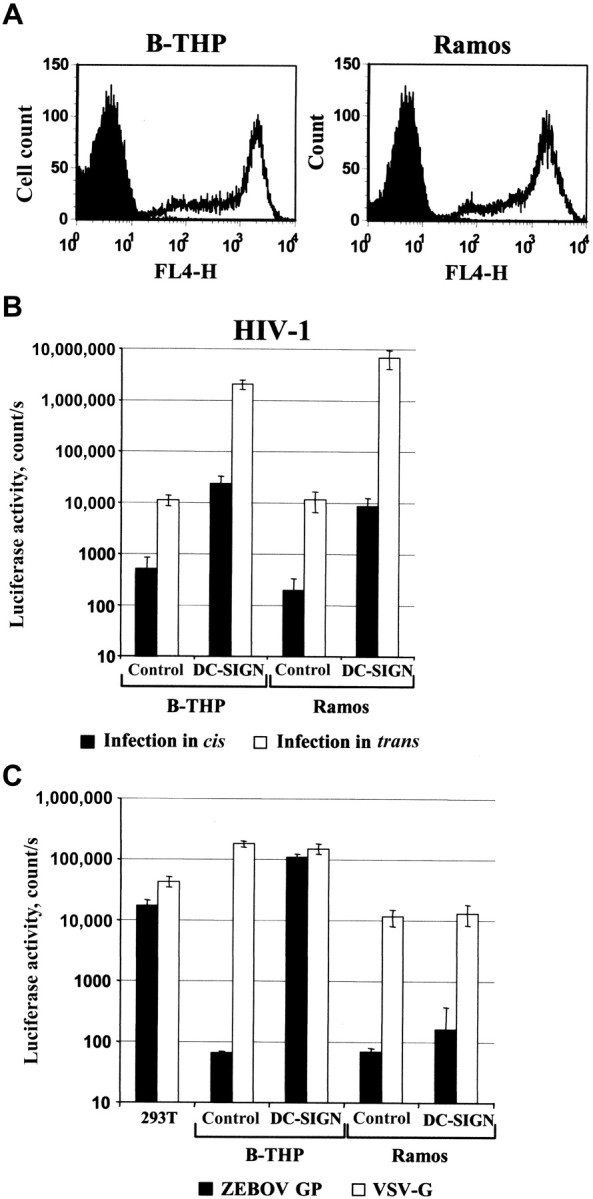

DC-SIGN-mediated augmentation of EBOV GP-driven entry into B cells: cell line dependence and the important role of the concentration of virions on the cell surface. We next investigated whether DC-SIGN augmented EBOV GP-driven entry into B-THP cells is specific to this particular cell line or whether it can be observed with Ramos B cells expressing exogenous DC-SIGN [28]. FACS analyses revealed that both cell lines expressed very similar amounts of DC-SIGN (figure 4A) and that, on both cells, DC-SIGN was readily internalized after ligand binding (figure 3C) (data not shown). Accordingly, both cell lines were equally adept in transferring HIV-1 to T cells, although transmission was partly due to direct infection of the transmitting cells (figure 4B), as described elsewhere [30, 34, 35]. In contrast, only B-THP DC-SIGN cells-not Ramos DCSIGN cells-were readily susceptible to EBOV GP-dependent infection. Both cell lines could be infected by vesicular stomatitis virus GP-bearing pseudotypes, although with different efficiencies (figure 4C), suggesting that, apart from DC-SIGN, another molecule is required for EBOV GP-dependent entry into Ramos B cells. In this case, the role of DC-SIGN in EBOV infection might be limited to concentrating virions on the cell surface, which, in turn, might increase entry via so far unidentified receptor(s).

Figure 4.

DC-SIGN (dendritic cell—specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin) on B-THP cells—but not on Ramos B cells—efficiently augments Ebola virus (EBOV) glycoprotein (GP)-dependent infection. A, B-THP and Ramos B cells express comparable levels of exogenous DC-SIGN. DC-SIGN expression was determined by fluorescence- activated cell sorting analysis. B, B-THP and Ramos B cells expressing exogenous DC-SIGN augment HIV-1 infectivity to comparable levels. The indicated cell lines were incubated with 5 ng of a replicationcompetent HIV-1 reporter virus, washed, and either cocultivated with CEMx174 R5 target cells or maintained in medium, and luciferase activities in cellular lysates were determined. A representative experiment is shown. Error bars denote SDs. C, B-THP DC-SIGN cells—but not Ramos DC-SIGN cells—augment EBOV GP-dependent infection with high efficiency. The indicated cell lines were inoculated with infectivity-normalized pseudotypes harboring the indicated GPs, and luciferase activities in cellular lysates were determined. A representative experiment is shown. Error bars denote SDs. VSV-G, vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein.

To address the hypothesis that the attachment step limits infection of B-THP cells, virions were concentrated onto the surface of B-THP and B-THP DC-SIGN cells by centrifugation, as described elsewhere [26]. This procedure, known as “spinoculation” [26], substantially increased infection of both cell lines, and infectious entry into otherwise nonpermissiveB-THP control cells was readily detectable under these conditions (figure 5A). Thus, B-THP cells most likely express low levels of receptor, which can be engaged efficiently only by EBOV GP—bearing viruses after augmentation of virus attachment, either by DC-SIGN or by spinoculation. To extend these observations, we assessed whether augmentation of viral attachment by spinoculation allowed EBOV GP-driven entry into a broader panel of B cell lines. Indeed, the B cell line NC-37 [28] was found to be susceptible to EBOV GP pseudotypes under these conditions, and infectious entry was further enhanced by expression of exogenous DC-SIGN (figure 5B). Similarly, infection of the BC 11 cell line was readily detectable after spinoculation. In contrast, 7 other B cell lines, including Nalm-6 and Ramos B cells (figure 5B) (data not shown), remained refractory, suggesting absent or extremely low receptor expression on these cells.

Figure 5.

Spinoculation allows Zaire Ebola virus (ZEBOV) glycoprotein (GP)-driven infection of certain B cell lines. A, Spinoculation [26] renders parental B-THP cells permissive to ZEBOV GP-dependent infection. The indicated cell lines were either inoculated with reporter viruses bearing the indicated GPs or mock inoculated, incubated at 37°C or centrifuged for 1 h at 1200 rpm, and then incubated at 37°C for 3 days. Thereafter, luciferase activities in cell lysates were determined. A representative experiment is shown. Error bars denote SDs. A t test (2-tailed) for dependent samples was used for statistical analysis. B, Spinoculation of a panel of B cell lines. The indicated B cell lines were infected as described above, and luciferase activities in cell lysates were determined. A representative experiment is shown. Error bars denote SDs.

Modest contribution of DC-SIGN and other mannose-specific lectins to ZEBOV infection of MDDCs. Multiple studies demonstrate that exogenous DC-SIGN expression strongly enhances EBOV infection. However, the effect of endogenous DCSIGN expression on EBOV infection has not been determined. We therefore assessed whether infection of MDDCs by replication-competent ZEBOV can be inhibited by the mannose polymer mannan, which blocks ligand binding to DC-SIGN and other mannose-specific lectins. Preincubation of MDDCs with mannan before exposure to ZEBOV reduced infection significantly (P = .029), indicating that factors other than DCSIGN contribute substantially to ZEBOV infection of these cells (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Infection of monocyte-derived dendritic cells by Zaire Ebola virus (ZEBOV) is partially due to engagement of mannose-specific lectins. Dendritic cells were derived from monocytes by cytokine treatment and infected with ZEBOV in the presence or absence of mannan. At 48 h after infection, IFA was performed with an anti-ZEBOV goat serum and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody. Nuclei were visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining. The percentage of infected cells was determined. A and B, Results of a representative experiment. Similar results were obtained in an independent experiment. A t test (1-tailed) for dependent samples was used for statistical analysis.

Discussion

We show that certain B cell lines are permissive to EBOV GP-driven entry, possibly because of expression of very low levels of receptor, and that DC-SIGN augments efficient infectious entry into these cells. The latter does not require intact internalization motifs in the DC-SIGN cytosolic tail and, thus, might not involve trafficking of virions into endosomal compartments. Moreover, we demonstrate that infection of MDDCs by replication-competent ZEBOV is only partially due to DCSIGN or related lectins, indicating an important contribution of other cellular factors. Thus, our results hint toward a role for DC-SIGN as an EBOV attachment factor and not an entry receptor, and they suggest that DC-SIGN might not be essential for EBOV infection of DCs.

Filoviruses exhibit an extremely broad tropism, with only B and T cells being refractory to infection [2–4]. Thus, the filovirus receptor(s) might be ubiquitously expressed. However, its identity remains elusive. The cellular lectins DC-SIGN/R, human macrophage lectin specific for galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine (hMGL), asialoglycoprotein receptor I (ASGPRI), and liver and lymph node sinusoidal endothelial cell C-type lectin (LSECtin) were shown to augment cellular entry of filoviruses [7, 9–12, 36, 37] and to be expressed on relevant EBOV target cells, such as macrophages (DC-SIGN and hMGL), sinusoidal endothelial cells in the liver and lymph nodes (DC-SIGNR and LSECtin), and hepatocytes (ASGPRI). Engagement of these lectins might focus filovirus infection on specific targets and might contribute to the distinct cell and organ tropism displayed by filoviruses at different stages of infection [6, 38].

We previously failed to detect appreciable EBOV GP-mediated entry into lymphoid cells expressing exogenous DCSIGN [11]. To us, therefore, it was unexpected that DC-SIGN/R expression rendered B-THP cells permissive. The discrepancy between our previous and present observations might be the result of differences in DC-SIGN expression levels, which strictly correlate with the efficiency of augmentation of EBOV GP-dependent infection [11], or of variations in the expression of endogenous EBOV receptor(s) on the target cells used in both studies. In any event, data published elsewhere [9] and the results of the present study indicate that expression of DCSIGN on certain lymphoid cell lines is sufficient for robust EBOV GP-dependent infection, and they pose the question of whether DC-SIGN functions as an EBOV receptor.

If DC-SIGN alone can act as a receptor for filovirus entry into B cells, DC-SIGN expression on different, otherwise nonpermissive B cell lines should allow for viral infection. Moreover, EBOV engagement of this lectin should lead to uptake of virions into intracellular vesicles, where the fusion machinery in GP is activated upon cleavage by cellular cathepsins [18, 39]. Our results suggest that DC-SIGN/R might not fulfill either criterion. Thus, alterations in the DC-SIGN/R cytoplasmic tails that prevent efficient internalization of lectin-ligand complexes did not abrogate augmentation of EBOV GP-mediated entry. DC-SIGN/R-mediated endocytic uptake of virions might therefore be dispensable for enhancement of EBOV infection. Similar observations have recently been reported for dengue virus [32], which also engages DC-SIGN [40, 41]. Furthermore, comparable expression of exogenous DC-SIGN on B-THP and Ramos B cells rendered only the former cells readily susceptible to EBOV GP-dependent infection. Thus, apart from DC-SIGN, other factors might be required to allow EBOV GP-mediated cellular entry. In fact, our observation that artificial concentration of virions on the cell surface allows for EBOV GP-driven entry into B-THP and NC-37 B cells indicates that these cells express very low levels of EBOV receptors, which can only be engaged efficiently once a substantial number of viral particles are attached to the cell surface. Such conditions might be established by DC-SIGN expression, which facilitates efficient capture of virions harboring EBOV GP [11]. Taken together, these results point to a function of DC-SIGN as an attachment factor and not a receptor for filoviruses.

Exogenous DC-SIGN/R profoundly augment filovirus infection. However, similar observations have not been documented for endogenous DC-SIGN/R. It has recently been reported that a subpopulation of B cells in human blood expresses DC-SIGN and that expression is augmented after B cell activation [42]. We therefore thought to study EBOV GP-dependent entry into DC-SIGN-positive, primary B cells, but we failed to detect DCSIGN on these cells (data not shown), for reasons that are, at present, unclear. Similarly, we also failed to detect endogenous DC-SIGN on any of the nontransduced B cells analyzed, including the BC 11 line, which supported EBOV GP-driven infectious entry (data not shown), suggesting that lectin expression on cell lines does not mirror that reported for activated, primary B cells. MDDCs express high levels of endogenous DC-SIGN and are permissive to EBOV infection [25, 43, 44]. DC-SIGN-positive cells with DC morphology were also shown to be infected in ZEBOV-inoculated macaques [2]. However, entry of ZEBOV into MDDCs was only ∼50% dependent on mannose-specific lectins, such as DC-SIGN, implying an important contribution of other cellular factors. Of note, several reports suggest that DC-SIGN—positive cells in lymphoid tissues might not be of DC origin but, rather, of macrophage origin [14, 45, 46]. These observations and the findings of the present study raise doubts about an important contribution of DC-SIGN—mediated infection of DCs to the spread of EBOV in the host.

Acknowledgments

Ramos and NC-37 B cell lines were obtained from the AIDS Reference and Reagent Program (Germantown, MD).We thank D. Littman for kindly providing cell lines expressing DC-SIGN (dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin) variants; S. Müller, for B cell lines; B. Vollrath, for p24-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; and B. Fleckenstein and K. von der Mark, for support.

Supplement sponsorship. This article was published as part of a supplement entitled “Filoviruses: Recent Advances and Future Challenges,” sponsored by the Public Health Agency of Canada, the National Institutes of Health, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Cangene, CUH2A, Smith Carter, Hemisphere Engineering, Crucell, and the International Centre for Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: none reported.

Presented in part: Filoviruses: Recent Advances and Future Challenges, International Centre for Infectious Diseases Symposium, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, 17–19 September 2006 (poster 18).

Financial support: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grants SFB466 [to A.M., S.P., and A.S.] and SFB535 and SFB593 [to P.M. and S.B.]); Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Klinische Forschung, University Hospital Erlangen (to A.S.). Supplement sponsorship is detailed in the Acknowledgments

References

- 1.Geisbert TW, Hensley LE. Ebola virus: new insights into disease aetiopathology and possible therapeutic interventions. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2004;6:1–24. doi: 10.1017/S1462399404008300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geisbert TW, Hensley LE, Larsen T, et al. Pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in cynomolgus macaques: evidence that dendritic cells are early and sustained targets of infection. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2347–70. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63591-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wool-Lewis RJ, Bates P. Characterization of Ebola virus entry by using pseudotyped viruses: identification of receptor-deficient cell lines. J Virol. 1998;72:3155–60. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3155-3160.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Z, Delgado R, Xu L, et al. Distinct cellular interactions of secreted and transmembrane Ebola virus glycoproteins. Science. 1998;279:1034–7. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimojima M, Takada A, Ebihara H, et al. Tyro3 family-mediated cell entry of Ebola and Marburg viruses. J Virol. 2006;80:10109–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01157-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pöhlmann S. Interaction of hemorrhagic fever viruses with dendritic cells. In: Lutz M, Romani N, Steinkasserer A, editors. Handbook of dendritic cells. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2006. pp. 829–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin G, Simmons G, Pöhlmann S, et al. Differential N-linked glycosylation of human immunodeficiency virus and Ebola virus envelope glycoproteins modulates interactions with DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. J Virol. 2003;77:1337–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1337-1346.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marzi A, Akhavan A, Simmons G, et al. The signal peptide of the ebolavirus glycoprotein influences interaction with the cellular lectins DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. J Virol. 2006;80:6305–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02545-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez CP, Lasala F, Carrillo J, Muniz O, Corbi AL, Delgado R. Ctype lectins DC-SIGN and L-SIGN mediate cellular entry by Ebola virus in cis and in trans. J Virol. 2002;76:6841–4. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6841-6844.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marzi A, Gramberg T, Simmons G, et al. DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR interact with the glycoprotein of Marburg virus and the S protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2004;78:12090–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.12090-12095.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simmons G, Reeves JD, Grogan CC, et al. DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR bind Ebola glycoproteins and enhance infection of macrophages and endothelial cells. Virology. 2003;305:115–23. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gramberg T, Hofmann H, Möller P, et al. LSECtin interacts with filovirus glycoproteins and the spike protein of SARS coronavirus. Virology. 2005;340:224–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geijtenbeek TB, Torensma R, Van Vliet SJ, et al. Identification of DCSIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell. 2000;100:575–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granelli-Piperno A, Pritsker A, Pack M, et al. Dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin/CD209 is abundant on macrophages in the normal human lymph node and is not required for dendritic cell stimulation of the mixed leukocyte reaction. J Immunol. 2005;175:4265–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bashirova AA, Geijtenbeek TB, van Duijnhoven GC, et al. A dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN)-related protein is highly expressed on human liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and promotes HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 2001;193:671–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pöhlmann S, Soilleux EJ, Baribaud F, et al. DC-SIGNR, a DC-SIGN homologue expressed in endothelial cells, binds to human and simian immunodeficiency viruses and activates infection in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2670–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051631398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh M, Helenius A. Virus entry: open sesame. Cell. 2006;124:729–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandran K, Sullivan NJ, Felbor U, Whelan SP, Cunningham JM. Endosomal proteolysis of the Ebola virus glycoprotein is necessary for infection. Science. 2005;308:1643–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1110656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon DS, Gregorio G, Bitton N, Hendrickson WA, Littman DR. DCSIGN-mediated internalization of HIV is required for trans-enhancement of T cell infection. Immunity. 2002;16:135–44. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaipan C, Soilleux EJ, Simpson P, et al. DC-SIGN and CLEC-2 mediate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capture by platelets. J Virol. 2006;80:8951–60. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00136-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller G, Shope T, Lisco H, Stitt D, Lipman M. Epstein-Barr virus: transformation, cytopathic changes, and viral antigens in squirrel monkey and marmoset leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:383–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.2.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connor RI, Chen BK, Choe S, Landau NR. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology. 1995;206:935–44. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pöhlmann S, Baribaud F, Lee B, et al. DC-SIGN interactions with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and 2 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2001;75:4664–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4664-4672.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baribaud F, Pöhlmann S, Sparwasser T, et al. Functional and antigenic characterization of human, rhesus macaque, pigtailed macaque, and murine DC-SIGN. J Virol. 2001;75:10281–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10281-10289.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baribaud F, Pöhlmann S, Leslie G, Mortari F, Doms RW. Quantitative expression and virus transmission analysis of DC-SIGN on monocytederived dendritic cells. J Virol. 2002;76:9135–42. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9135-9142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Doherty U, Swiggard WJ, Malim MH. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 spinoculation enhances infection through virus binding. J Virol. 2000;74:10074–80. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.10074-10080.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Modrof J, Muhlberger E, Klenk HD, Becker S. Phosphorylation of VP30 impairs Ebola virus transcription. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33099–104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203775200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu L, Martin TD, Carrington M, KewalRamani VN. Raji B cells, misidentified as THP-1 cells, stimulate DC-SIGN-mediated HIV transmission. Virology. 2004;318:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marzi A, Wegele A, Pöhlmann S. Modulation of virion incorporation of Ebolavirus glycoprotein: effects on attachment, cellular entry and neutralization. Virology. 2006;352:345–56. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burleigh L, Lozach PY, Schiffer C, et al. Infection of dendritic cells (DCs), not DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of human immunodeficiency virus, is required for long-term transfer of virus to T cells. J Virol. 2006;80:2949–57. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2949-2957.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engering A, Geijtenbeek TB, Van Vliet SJ, et al. The dendritic cellspecific adhesion receptor DC-SIGN internalizes antigen for presentation to T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:2118–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lozach PY, Burleigh L, Staropoli I, et al. Dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN)-mediated enhancement of dengue virus infection is independent of DCSIGN internalization signals. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23698–708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sol-Foulon N, Moris A, Nobile C, et al. HIV-1 Nef-induced upregulation of DC-SIGN in dendritic cells promotes lymphocyte clustering and viral spread. Immunity. 2002;16:145–55. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nobile C, Petit C, Moris A, et al. Covert human immunodeficiency virus replication in dendritic cells and in DC-SIGN-expressing cells promotes long-term transmission to lymphocytes. J Virol. 2005;79:5386–99. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5386-5399.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turville SG, Santos JJ, Frank I, et al. Immunodeficiency virus uptake, turnover, and 2-phase transfer in human dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;103:2170–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becker S, Spiess M, Klenk HD. The asialoglycoprotein receptor is a potential liver-specific receptor for Marburg virus. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:393–9. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-2-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takada A, Fujioka K, Tsuiji M, et al. Human macrophage C-type lectin specific for galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine promotes filovirus entry. J Virol. 2004;78:2943–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.2943-2947.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baribaud F, Doms RW, Pöhlmann S. The role of DC-SIGN and DCSIGNR in HIV and Ebola virus infection: can potential therapeutics block virus transmission and dissemination? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2002;6:423–31. doi: 10.1517/14728222.6.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schornberg E, Matsuyama S, Kabsch K, Delos S, Bouton A, White J. Role of endosomal cathepsins in entry mediated by the Ebola virus glycoprotein. J Virol. 2006;80:4174–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.4174-4178.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navarro-Sanchez E, Altmeyer R, Amara A, et al. Dendritic-cell-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin is essential for the productive infection of human dendritic cells by mosquito-cell-derived dengue viruses. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:723–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tassaneetrithep B, Burgess TH, Granelli-Piperno A, et al. DC-SIGN (CD209) mediates dengue virus infection of human dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:823–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rappocciolo G, Piazza P, Fuller CL, et al. DC-SIGN on B lymphocytes is required for transmission of HIV-1 to T lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e70. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bosio CM, Aman MJ, Grogan C, et al. Ebola and Marburg viruses replicate in monocyte-derived dendritic cells without inducing the production of cytokines and full maturation. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1630–8. doi: 10.1086/379199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahanty S, Hutchinson K, Agarwal S, McRae M, Rollin PE, Pulendran B. Cutting edge: impairment of dendritic cells and adaptive immunity by Ebola and Lassa viruses. J Immunol. 2003;170:2797–801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gurney KB, Elliott J, Nassanian H, et al. Binding and transfer of human immunodeficiency virus by DC-SIGN+ cells in human rectal mucosa. J Virol. 2005;79:5762–73. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5762-5773.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krutzik SR, Tan B, Li H, et al. TLR activation triggers the rapid differentiation of monocytes into macrophages and dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:653–60. doi: 10.1038/nm1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]