In selecting ssDNA over dsDNA, the RAD51 DNA strand exchange protein has to overcome the entropy associated with straightening of single‐strand DNA upon nucleoprotein filament formation. New work in The EMBO Journal (Paoletti et al, 2020), combined biophysical analysis of the RAD51–ssDNA interaction with mathematical modeling to show that the flexibility of DNA positively correlates with nucleation and extension of the RAD51 nucleoprotein filament and that the entropic penalty associated with restricting ssDNA flexibility is offset by a strong RAD51–RAD51 interaction within the nucleoprotein filament.

Subject Categories: DNA Replication, Repair & Recombination; Structural Biology

New biophysical and modeling work suggests how the entropy cost associated with single‐strand DNA straightening is offset within recombinase‐bound nucleoprotein filaments.

Homologous recombination (HR) is one of the most enigmatic processes in DNA metabolism. It ensures faithful maintenance of genomic integrity and is a fundamental driver of evolution. The nucleoprotein filament assembled by the conserved strand exchange protein (aka recombinase) RAD51 on single‐strand DNA (ssDNA) facilitates the central step in HR. In HR, homology‐directed DNA repair, and at stalled or damaged DNA replication forks, RAD51 needs to discriminate between ssDNA and double‐strand DNA (dsDNA), as only the RAD51–ssDNA nucleoprotein filament is HR‐proficient. While recombination mediators, such as human BRCA2 or yeast Rad52, enable RAD51 to efficiently compete with the ssDNA‐binding protein RPA to facilitate formation of the nucleoprotein filament on ssDNA, the mechanisms enabling discrimination between ssDNA and dsDNA have remained less clear. Current structural knowledge is suggestive of RAD51 interacting in similar manners with both ssDNA and dsDNA. Formation of the nucleoprotein filament on ssDNA, however, is expected to incur a significant entropic cost, as straightening flexible ssDNA through formation of the rigid nucleoprotein filament is energetically costlier than that of dsDNA; nevertheless, it seems to proceed faster (Candelli et al, 2014). What then offsets this energetic cost? In their new study (Paoletti et al, 2020), the Esashi and Dushek groups answer this question by quantifying and comparing the polymerization of purified human RAD51 protein onto several types of oligonucleotide‐DNA substrates of different flexibilities (Fig 1).

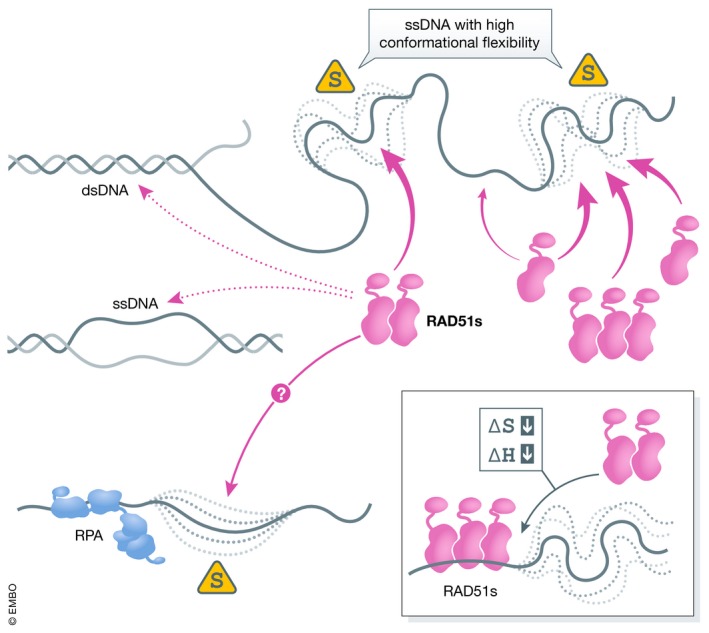

Figure 1. Enhanced preference for flexible DNA may facilitate discrimination between desired and undesired loci for RAD51 nucleoprotein filament nucleation.

In their single‐stranded forms, different ssDNA sequences display different degrees of flexibility and hence have different conformational flexibilities. Yet, RAD51 filament formation is enhanced on flexible ssDNA over more rigid sequences and dsDNA. Loss in conformational entropy associated with RAD51 nucleoprotein filament sequestration of these flexible regions is compensated by higher enthalpy of the protomer–protomer interface within the filament.

Employing surface plasmon resonance (SPR), a label‐free approach to analyze the kinetics of macromolecular interactions, and small‐angle X‐ray scattering (SAXS), the authors observed faster rates of nucleoprotein filament formation on ssDNA than on a dsDNA 50‐mer, but similar stability of the formed filament in either case, in agreement with previous single‐molecule studies following RAD51 nucleoprotein formation on long ssDNA (Candelli et al, 2014). The authors then used mixed‐base oligonucleotide substrates of varying lengths to characterize the initial steps of RAD51 association with both ssDNA and dsDNA. SAXS experiments were used to determine the persistence length (i.e., flexibility) of 50‐mer DNA substrates composed of highly rigid poly‐dT oligonucleotides, highly flexible poly‐dA ssDNA, and mixed‐nucleotide DNA (poly‐dN). Similar analyses were performed with corresponding dsDNA substrates, and SPR experiments were then used to determine kinetics of RAD51 polymerization on these substrates. Under conditions that largely prevent ATP hydrolysis and thereby RAD51 turnover, a minimum of four RAD51 molecules were required to form a quasi‐stable filament nucleus, while five or more RAD51 molecules formed highly stable nuclei on ssDNA, again in nice agreement with two earlier single‐molecule studies (Candelli et al, 2014; Subramanyam et al, 2016), but now also providing more accurate rate constants. Interestingly, on dsDNA substrates, only two molecules of RAD51 were required to form a quasi‐stable nucleus, with three or more RAD51 molecules already forming highly stable nuclei; this advantage, however, was lost on longer DNA molecules.

To further dissect RAD51 nucleoprotein filament formation, Paoletti et al (2020) developed a mathematical model describing the kinetics of RAD51 oligomerization in solution and for both ssDNA and dsDNA. This model, based on an ordinary differential equation (ODE), was then fit to experimental SPR binding data using approximate Bayesian computation (ABC) and sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) calculations. Modeling confirmed that RAD51 filament nucleation and elongation is faster on ssDNA compared with dsDNA, and suggested that the high affinity of RAD51 molecules to each other may be the key driver enabling RAD51 to preferentially bind ssDNA over dsDNA substrates.

Paoletti et al rationalized their observations by developing a bend‐to‐capture (BTC) model, which explains how the flexibility of DNA directly influences polymerization kinetics of the RAD51 recombinase. According to this BTC model, sequential interaction of a soluble RAD51 monomer/oligomer with the exposed interface of an existing DNA‐bound RAD51 monomer and with the exposed scaffold DNA helps polymerization by avoiding steric clashes. Flexible unbound DNA immediately next to the existing DNA‐bound RAD51 polymer allows for more conformations that are compatible with further addition of RAD51, and is malleable to protein‐induced deformation. The authors thus propose that in addition to its many important roles, RAD51 can also function as a sensor of locally flexible DNA, which may be found at sites where RAD51 nucleoprotein formation is most appropriate, allowing speculations why certain genome loci are more difficult to repair than others.

While the above experiments demonstrated the role of flexibility of DNA substrates in facilitating RAD51 nucleation and polymerization, this property does not influence the stability of the RAD51 nucleoprotein filament on either ssDNA or dsDNA, as shown in previous biophysical studies (Mine et al, 2007; Candelli et al, 2014; Brouwer et al, 2018). This is important, because the flexibility of longer ssDNA substrates introduces a larger entropic penalty for the formation of stiff and stable RAD51 polymers, and should in turn decrease RAD51 filament stability. To address this discrepancy, Paoletti et al suggest that the enthalpic gain resulting from RAD51 incorporation into an existing RAD51 filament is sufficiently large to overcome the entropic penalty imposed by reduction in conformational entropy of the intrinsically flexible ssDNA. This entropic penalty compensation (EPC) mechanism would ensure that the binding energy of RAD51 polymerization is significant enough to compensate for any DNA‐dependent entropic penalties. Taking advantage of a known RAD51 mutant with a phenylalanine‐to‐glutamate substitution (F86E) that significantly reduces protomer–protomer affinity without affecting the overall protein structure, the authors were indeed able to demonstrate that such a mutant recombinase has lower affinity for ssDNA and dsDNA compared with the wild‐type protein and that the energetic contribution of RAD51 filament formation is significant enough to offset the entropic penalties associated with constraints imposed on flexible DNA by the RAD51 polymerization.

The “DUET” (“Dna molecUlar flExibiliTy”) model proposed by the authors explains how DNA flexibility and protomer–protomer affinity helps RAD51 nucleation and polymerization onto flexible ssDNA, with preference over dsDNA. Although a number of previous studies (Candelli et al, 2014; Lee et al, 2015; Qi et al, 2015; Subramanyam et al, 2016; Brouwer et al, 2018) have analyzed RAD51 nucleoprotein filament formation and its dynamics, the data and the mathematical framework underlying the DUET model developed by Paoletti et al importantly take into account the entropic nature of the substrate on which HR‐active RAD51 species form. The entropic penalty compensation explored by Paoletti et al (2020) raises a number of provocative questions; it would be exciting to see further application of their experimental/computational workflow. The strength of the RAD51 protomer–protomer interaction as defining factor offsetting the entropic loss during nucleoprotein filament formation should bring new attention to the importance of this interface. Recent work by Brouwer et al (2018) has revealed the presence of two distinct interfaces within the RAD51‐ATP filament. Do these interfaces reflect adaptation of the growing filament to different ssDNA sequences with distinct flexibilities? Will conditions that permit ATP hydrolysis exacerbate or dampen the DUET‐based discrimination between flexible and rigid DNA substrates? Will the BTC model require adjustments when using post‐translationally modified RAD51, whose different protomer–protomer interface dynamics enable it to compete with RPA for ssDNA binding (Subramanyam et al, 2016)?

The mechanism proposed by the authors also helps extend our understanding of the processes involved in the formation of the RAD51 nucleoprotein filament on RPA‐bound ssDNA. Here, the formation of a stable nucleus of RAD51 molecules on ssDNA may take place when the individual DNA‐binding domains of RPA transiently dissociate from DNA, yielding highly flexible ssDNA on which RAD51 can nucleate and elongate to eventually replace RPA (Gibb et al, 2014; Pokhrel et al, 2019). The DUET model further explains how limited flexibility of ssDNA may restrict RAD51 polymerization to resected ssDNA with a free 3′ overhang, while limiting spontaneous unwanted RAD51 filament formation on ssDNA arising during transcription or DNA replication. In addition, the present observations provide a general understanding of the factors that influence the recruitment of DNA‐binding proteins to sites of DNA damage. The workflow developed by the authors will be thus instrumental in testing the BTC model in the context of recombination mediation by BRCA2, whose interaction with RAD51 alters the RAD51–RAD51 interface by enhancing selectivity for ssDNA (Carreira et al, 2009).

The EMBO Journal (2020) 39: e104547

See also: https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2019103002 (April 2020)

References

- Brouwer I, Moschetti T, Candelli A, Garcin EB, Modesti M, Pellegrini L, Wuite GJL, Peterman EJG (2018) Two distinct conformational states define the interaction of human RAD51‐ATP with single‐stranded DNA. EMBO J 37: e98162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelli A, Holthausen JT, Depken M, Brouwer I, Franker MAM, Marchetti M, Heller I, Bernard S, Garcin EB, Modesti M et al (2014) Visualization and quantification of nascent RAD51 filament formation at single‐monomer resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 15090–15095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreira A, Hilario J, Amitani I, Baskin RJ, Shivji MK, Venkitaraman AR, Kowalczykowski SC (2009) The BRC repeats of BRCA2 modulate the DNA‐binding selectivity of RAD51. Cell 136: 1032–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb B, Ye LF, Kwon Y, Niu H, Sung P, Greene EC (2014) Protein dynamics during presynaptic‐complex assembly on individual single‐stranded DNA molecules. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21: 893–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Terakawa T, Qi Z, Steinfeld JB, Redding S, Kwon Y, Gaines WA, Zhao W, Sung P, Greene EC (2015) Base triplet stepping by the Rad51/RecA family of recombinases. Science 349: 977–981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mine J, Disseau L, Takahashi M, Cappello G, Dutreix M, Viovy JL (2007) Real‐time measurements of the nucleation, growth and dissociation of single Rad51‐DNA nucleoprotein filaments. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 7171–7187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti F, El‐Sagheer AH, Allard J, Brown T, Dushek O, Esashi F (2020) Molecular flexibility of DNA as a key determinant of RAD51 recruitment. EMBO J 39: e103002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel N, Caldwell CC, Corless EI, Tillison EA, Tibbs J, Jocic N, Tabei SMA, Wold MS, Spies M, Antony E (2019) Dynamics and selective remodeling of the DNA‐binding domains of RPA. Nat Struct Mol Biol 26: 129–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Z, Redding S, Lee Ja Y, Gibb B, Kwon Y, Niu H, Gaines William A, Sung P, Greene Eric C (2015) DNA sequence alignment by microhomology sampling during homologous recombination. Cell 160: 856–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanyam S, Ismail M, Bhattacharya I, Spies M (2016) Tyrosine phosphorylation stimulates activity of human RAD51 recombinase through altered nucleoprotein filament dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: E6045–E6054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]