Abstract

The present study assessed the functional consequences of viral infection with a neurotropic coronavirus, designated MHV OBLV, that specifically targets central olfactory structures. Using standard operant techniques and a `go, no-go' successive discrimination paradigm, six BALB/c mice were trained to discriminate between the presentation of an air or odor stimulus (three mice for each of the odorants propanol and propyl acetate). Two additional BALB/c mice were trained to discriminate between the presentation of air and the presentation of either vanillin or propionic acid. Following criterion performance, each mouse received an additional 2000 trials of overtraining. At completion of overtraining one mouse from the propanol and propyl acetate groups were allocated as untreated. The remaining six mice were inoculated with 300 μl of the OBLV stock per nostril for a total of 1.5 × 106 p.f.u. in 600 μl. Following a 1 month rest, untreated and inoculated animals were again tested on their respective air versus odor discrimination task. Untreated animals immediately performed at criterion levels. In contrast, inoculated animals varied in their capacity to discriminate between air and odorant. Five of the six inoculated mice showed massive disruption of the olfactory bulb, including death of mitral cells; the other was more modestly affected. In addition, the density of innervation of the olfactory mucosa by substance P-containing trigeminal fibers is also affected by inoculation. Those mice that remained anosmic to the training odorants had the most severe reduction in mitral cell number and substance P fiber density among the inoculated animals.

Introduction

Data accumulated from a number of chemosensory clinical centers suggest that viral upper respiratory infection is one of the most common causes of anosmia/hyposmia (Mott and Leopold, 1991). Although case studies in humans strongly support the notion that viruses cause olfactory dysfunction, the actual basis for viral-induced loss is unknown. Similarly, the pathogenesis of post-viral olfactory loss has been more a subject of conjecture than substantive analyses. Coronaviruses are but one of several families of virus that cause upper respiratory infections and have been implicated in post-viral olfactory loss (Larson et al., 1980; Valenti, 1984; Evans and Kaslow, 1997). Interestingly, mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), including the JHM and many other strains, are murine coronaviruses that are neuropathic and have the capacity to spread to the CNS via the olfactory pathway following intranasal inoculation, causing fatal encephalitis or a persistent encephalopathy (Barthold, 1988; Perlman et al., 1989). A variant of the MHV JHM strain, termed OBLV (for olfactory bulb line variant), was adapted by growth on an oncogene-immortalized olfactory bulb-derived cell line (Gallagher et al., 1991). In the accompanying paper, we provide a detailed examination of the lesion that occurs following intranasal inoculation with the OBLV variant of MHV JHM and demonstrate that it selectively targets central olfactory structures, in particular the olfactory bulb (Schwob et al., 2001). Following infection, the bulb undergoes a massive degree of spongiotic change and neuronal degeneration throughout its extent (Schwob et al., 2001). Spongiotic degeneration is particularly prominent in the outer part of the external plexiform layer and, to a lesser extent, the internal granular layer. In short, the glomerular layer is completely detached from the remaining deeper layers of the bulb. Further, there is a lesser degree of damage to the lateral olfactory tract and piriform cortex. In addition to the central damage, there are also reflected changes in the epithelium as a consequence of damage to the bulb. Within the epithelium there is a coincident increase in immature neurons and reciprocal decrease in mature neurons that is highly similar to the histopathology of one set of patients who complain of post-viral olfactory loss (Yamagishi et al., 1988, 1990, 1994; Moran et al., 1992).

The above constellation of pathological findings have led to the suggestion that olfactory bulb damage, resulting from infection with a modified/adapted neurotropic virus, might be responsible for some types of olfactory dysfunction in humans (Schwob et al., 2001). In fact, the notion that post-viral olfactory loss might be the result of damage to central structures such as the olfactory bulb is not new. Stroop discusses in detail the potential for a number of viruses to infect and damage central olfactory structures, affect brain neurotransmitter levels and induce behavioral abnormalities (Stroop, 1995). Therefore, the present study examined the functional consequences of OBLV infection with respect to performance on a simple air versus odor discrimination task.

Materials and methods

Animals

Eight 12-week-old male BALB/c mice (designated behavioral test animals) were housed individually in a temperature and humidity controlled Biohazard Level II vivarium. Throughout the course of all psychophysical training and testing, daily food intake was controlled in order to provide the necessary motivation for the behavioral task. Although each animal was maintained under an individualized food restriction schedule, the end result for all animals was a reduction in body weight to 80% of free feeding levels. An additional 12 non-behaviorally trained, food-restricted and 12 non-behaviorally trained, ad libitum fed mice were used for studies of viral clearance from brain and lungs after intranasal inoculation.

Control of operant task and stimulus delivery

A computer-automated system shaped the behavioral task, monitored and recorded the responses of the animals and controlled, on a trial-by-trial basis, stimulus generation, stimulus delivery and the presentation of reinforcement (Youngentob et al., 1990, 1991a, b).

Odorant stimuli were generated according to previously established methods (Youngentob et al., 1990, 1991b) using standard flow dilution olfactometry and computer-driven electronic mass flow controllers (Teledyne Hastings Raydist Co., Hampton, VA). A Balston Clean Air Package (Balston Co., Lexington, MA) provided filtered, deodorized and dehumidified air to each of five parallel stimulus channels (four odorants and a `blank') plus diluent lines and a carrier air stream. The parallel stimulus channels were each controlled by separate computer-activated, three-way Teflon solenoid valves (General Valve Co., Fairfield, NJ) which converged into a common manifold and the carrier air stream. Saturated vapor was produced by sparging purified air through 250 ml gas washing bottles immersed in a constant temperature bath (Neslab, Newington, NH) maintained at 20°C. The final flow output of each stimulus channel was a constant 400 cc/min while the carrier air-stream was maintained at a constant 3600 cc/min. As a result, the total flow presented to the testing chamber during the presentation of a stimulus was 4.0 l/min. During the inter-trial interval, air flowed through the testing chamber at 3600 cc/min.

Behavioral chamber

The basic chamber consisted of a Delrin sniffing port attached to a Plexiglas tunnel (length 29 cm, diameter 6 cm). The entrance hole to the sniffing port was 4.8 cm in diameter and centered 2.5 cm from the tunnel floor. The sniffing port tapered over a distance of 5.2 cm to reach a 2 cm diameter diffusing screen where stimuli were delivered. Trial-initiating responses and stimulus sampling were monitored by two photobeams mounted across the sniffing port, one 1 cm and the other 2.5 cm from the diffusing screen. A stainless steel cup for reinforcement delivery was mounted at the end of the tunnel opposite the sniffing port. Contact between the cup and a stainless steel plate mounted on the tunnel floor was detected by a touch-sensitive circuit. Completion of the circuit by the mouse resulted in the delivery of 0.01 cc of liquid vanilla Ensure (Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, OH) reinforcement. Air from the tunnel was continuously exhausted by a vacuum ring positioned around the circumference of the Plexiglas tunnel and located 6 cm from the sniffing port and 23 cm from the end of the tunnel. In order to prevent room air from being drawn into the tunnel, a purified air input was provided at the end opposite the sniffing port. In this manner, odorant stimuli were isolated to the area between the sniffing port and the ring vacuum.

The entire operant chamber and olfactometer were housed in a constant temperature controlled room modified to accommodate Level II biohazards.

Odorants

The odorants used in this study were propanol, propyl acetate, propionic acid and vanillin. Propanol and propyl acetate were chosen since these odorants have been previously studied behaviorally in mice (Youngentob and Margolis, 1999; unpublished data). Moreover, although specific data on the relative sensitivity of the olfactory and trigeminal systems to these compounds is not available in this species, electrophysiological recordings of trigeminal responses in rats (Silver and Moulton, 1982) and human perceptual data (Doty, 1975; Doty et al., 1978) to qualitatively similar odorants suggest that sensitivity to these odorants is predominantly olfactory, with a small trigeminal contribution. Vanillin and propionic acid contrast with each other in that propionic acid is a strong trigeminal stimulant to human observers and in rat electrophysiological recordings (Silver and Moulton, 1982), whereas vanillin is predominantly, if not exclusively, a cranial nerve one stimulant (Doty, 1975; Doty et al., 1978). The concentration of each odorant was chosen such that their perception, at least to human observers, were matched for intensity and were well above threshold. Each odorant was always presented as a unitary stimulus. The concentrations were: propanol 2.5%, propyl acetate 0.4%, vanillin 1.25% and propionic acid 0.5% (concentration is expressed as percent vapor saturation at 10°C).

Behavioral training and procedures

A discrete-trials `go, no-go' successive discrimination paradigm was used to train mice to detect the presence of propanol (n = 3), propyl acetate (n = 3) and either vanillin or propionic acid (n = 2) (i.e. in these mice the discrete presentation of either vanillin or propionic acid had the valence of signalling reinforcement). The training procedures used to shape the air-odor discrimination were similar to those described by Slotnick (Slotnick, 1984) and are reported in detail elsewhere (Youngentob et al., 1991a). Briefly, using standard operant techniques, mice were trained to break and hold their interruption of the photobeams located inside the sniffing port. Breaking the photobeams resulted in simultaneous onset of a 2 kHz (80 dBA) tone and delivery of an odorant stimulus to the diffusing screen for a maximum of 6 s. Stimulus sampling for a minimum of 500 ms following stimulus delivery was enforced by a beam hold period of equal length that was defined for the animal by the length of the 2 kHz tone. Failure to maintain the minimum sampling time resulted in aborting the trial, turning off the chamber lights for 6 s and resetting the inter-trial interval (6 s). After the beam hold period had elapsed, the animal was trained to leave the sniffing port and lick the reinforcement cup for a minimum of 50 ms duration if an odor stimulus had been presented. This response terminated the trial simultaneously with reinforcement delivery. On trials in which only air was presented, the animal was required to withhold responding for the duration of the trial (responding in the presence of an air stimulus resulted in termination of the trial). Air and odor trials were presented in random order in blocks of 20 trials (10 odor, 10 air) with the restriction that not more than three trials of one type occurred in succession. No feedback was given for errors of omission (i.e. not responding during an odorant trial) or, except for lack of reinforcement, commission (i.e. responding during an air trial) and both response types contribute to the calculation of performance data (i.e. percent correct response). Testing continued in each session for a total of 200 trials (100 odorant, 100 air).

Experimental protocol

Following the establishment of criterion performance on the simple air versus odor discrimination task (>90% on 10 consecutive blocks of testing), each mouse was tested once per day for an additional 2000 trials of overtraining. The purpose of the overtraining was to maximize retention of the behavioral task beyond the 30 day recovery period that was used following viral inoculation (see below). In this regard, mice inoculated with OBLV show a general malaise that is characterized by a lack of grooming activity, a hunched, scruffy appearance, reduced food intake, decreased cage activity and decreased responsiveness to outside stimuli, which is time limited to the first weeks following infection. The overtraining period also permitted stabilization of performance and an assessment of pre-inoculation performance. All mice had comparable levels of pre-inoculation performance (mean ± SEM 92.4 ± 0.74). At the completion of overtraining, one mouse from each of the propanol and propyl acetate groups was allocated as untreated. The remaining six mice (two mice trained to respond to propanol, two mice trained to respond to propyl acetate and two mice trained to respond to the presentation of either vanillin or propionic acid) were inoculated, as described below, and then monitored until they recovered from the infection (as determined by a subjective return to normal cage activity such as grooming, climbing and general responsiveness to external stimuli). Similarly, untreated animals were rested for the same time period following overtraining. At the conclusion of the recovery period, both untreated and inoculated animals were again tested on their respective air versus odor discrimination problem.

Virus

Viral stock of OBLV (a gift of Dr Michael Buchmeier, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA) was propagated in OBL21A cells, which is an immortalized cell line derived from the neonatal olfactory bulb (Ryder et al., 1990) (a gift of Dr Connie Cepko), at a titer of 2.56 × 106 p.f.u./ml. The initial viral stock was isolated during persistent infection of the host cells (OBL21A) with mouse hepatitis strain JHM when the cytopathic infection shifted from plaque formation to syncytial formation on day 60 of passage (Gallagher et al., 1991).

Viral inoculation

Twenty minutes prior to anesthesia, each mouse was injected with glycopyrrolate (to reduce lung secretions) at a dose of 0.02 cc/g body wt. Animals were placed in a Plexiglas box and anesthetized by gas inhalation with Fluothane. Following achievement of a surgical plane of anesthesia, the mice were placed on their backs and their trachea rapidly intubated (via an oral route and through the laryngeal folds), using a 20 gauge i.v. catheter as a makeshift endotracheal tube. Anesthesia was maintained, using gas inhalation delivered to an open loop system attached to the i.v. catheter. The viral inoculum was delivered through a 22 gauge i.v. catheter that was inserted into each nostril. Each animal received 300 μl of OBLV virus stock per nostril over 20 min for a total of 1.5 × 106 p.f.u. in 600 μl. Following recovery from anesthesia each mouse was returned to its home cage.

Viral spread and clearance after inoculation

In addition to the eight mice used in the behavioral testing above, an additional 24 mice were inoculated with MHV OBLV and killed at 6, 9, 15 and 25 days post-inoculation. Three food-restricted and three non-food-restricted OBLV-infected animals were taken at each time point. Harvested tissues were freeze-thawed three times and macerated with a mortar and pestle into a 10% homogeneous mixture. Samples were then centrifuged at 10 000 r.p.m. to remove debris and the supernatant was used to perform plaque assays.

For the assay, serial dilutions of the sample supernatants from 100 to 10-4 were applied to DBT cells plated on 60 mm collagen-coated plates. The plates were incubated for 1 h with the sample at 37°C with intermittent gentle agitation, washed with phosphate-buffered saline and overlaid with 1% agar solution/maintenance medium. The plates were read 5 days later.

Histological analysis

At completion of the behavioral testing, all animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and perfused with Bouin's fluid, as previously described (Schwob et al., 1995). Following removal of the muscle tissue, teeth, soft palate and bone of the overlying skull, the tissues were placed in fixative for an additional 4 h, after which they were washed in distilled water overnight. The remaining bones were then decalcified using a formic acid/sodium citrate solution and the block encompassing brain, bulbs and nasal structures was embedded in paraffin and sectioned in keeping with previously published procedures (Schwob et al., 1995). A series of sections spaced at 5-15 μm intervals through the full anteroposterior (AP) extent of the bulb was mounted and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and a second series of non-adjacent sections stained only with hematoxylin in accordance with our standard protocol (Schwob et al., 1995). A set of five hematoxylin stained sections, evenly spaced along the AP axis of the bulb, was selected from each of the behavioral animals, both infected and normal, to determine the extent of mitral cell loss as a consequence of the viral inoculation and subsequent infection. Mitral cells were identified by their large size and location relative to other elements in the bulb. Mitral cell profiles that included a nucleolus were counted bilaterally and summed across the sections.

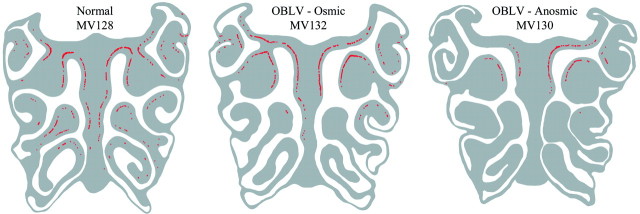

In addition, sections through the brain, bulbs and olfactory epithelium from all of the animals were stained with a polyclonal rabbit antiserum against rat substance P (Peninsula Laboratories, Belmont, CA) to label the subset of substance P-containing trigeminal fibers. Selected stained sections were digitally imaged and assembled into a high resolution mosaic. Care was taken to compare only those sections that were at equivalent levels along the AP axis of the epithelium because of inhomogeneities in the distribution of substance P-stained fibers along that axis, i.e. we compared sections that were the closest match to each other between series of sections that were spaced every 0.2 mm along the epithelium as exemplified by those illustrated in Figure 5. Labeled fibers were highlighted and the area they occupied was measured utilizing the image analysis software package IP Lab Spectrum (Scanalytics, Vienna, VA) and used to compare the status of the trigeminal innervation of the nasal cavity.

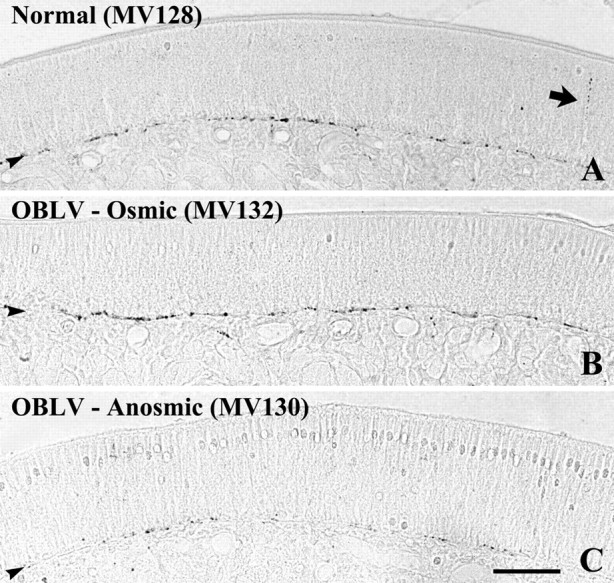

Figure 5.

The distribution of substance P-labeled axons is also different between normal versus osmic versus anosmic mice. The map was constructed by assembling a mosaic of digital images taken of the stained sections and then highlighting the fiber labeling. Note the marked reduction in tangential extent and in density of the labeled fibers in the anosmic mouse.

Results

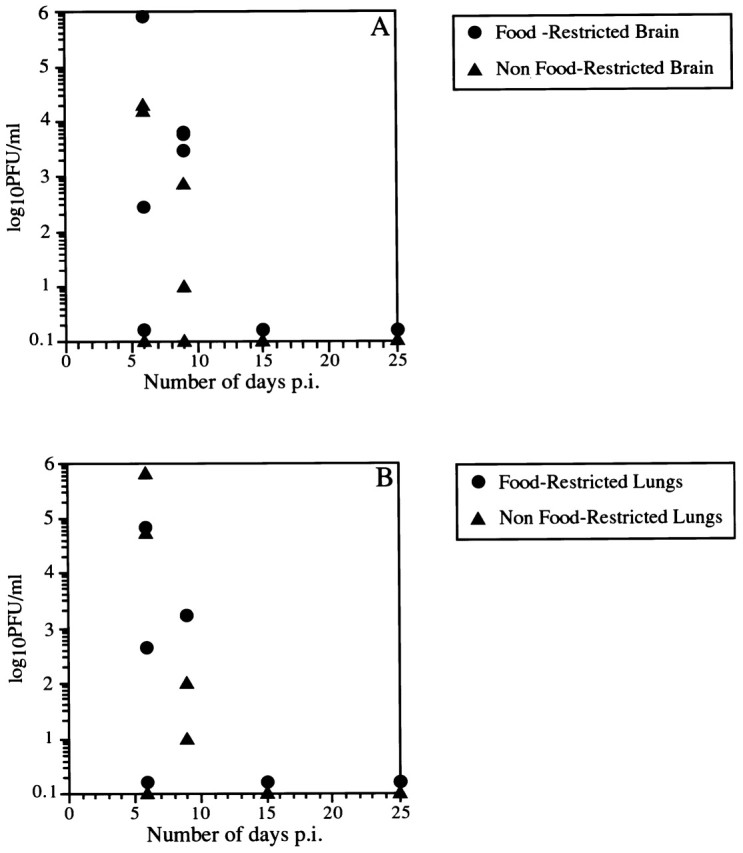

The results presented here describe the functional capacity of the olfactory system to perform an air versus odor discrimination task when compromised by a neurotropic virus whose primary target is the olfactory bulb. As a necessary prologue to the evaluation of behavioral capacity we determined the post-inoculation time course of OBLV clearance from brain, liver and lungs of both food-restricted and ad libitum fed mice (Figure 1). In both groups, virus reached comparable levels in the brains and was highest on day 6 post-inoculation; the geometric means at that time were 1.2 × 102 p.f.u./ml for food-restricted and 1.4 × 102 p.f.u./ml for ad libitum fed animals (Figure 1A). Virus levels were down on day 9 post-inoculation and was completely cleared from the brains of both groups by day 15 post-inoculation; clearance was slightly delayed in the food-restricted animals judging by the geometric means on day 9. Likewise, virus was highest in the lungs on day 6 post-inoculation in both groups of mice; geometric means at that time were 6.3 × 101 p.f.u./ml in food-restricted mice and 3.3 × 102 p.f.u./ml in ad libitum fed mice (Figure 1B). Virus was cleared from the lungs of both groups of mice by day 15 post-inoculation and appeared to be cleared equally well in both. Virus was not detected in any of the livers of either group at any of the time points. In keeping with the viral clearance data, the virus-induced malaise resolved and mice returned to normal cage activity by 1 month post-inoculation.

Figure 1.

After intranasal inoculation with MHV OBLV, infectious virus is cleared from both brain (A) and lung (B) within 2 weeks after infection. Prolonged food restriction (circles) did not substantially delay clearance relative to mice that were fed ad libitum throughout (triangles). Values of 0 p.f.u./ml are represented as 0.1 p.f.u./ml for the sake of clarity.

In accordance with the data on viral clearance and recovery from malaise, both untreated and virus-inoculated mice were rested for 1 month before testing. Untreated animals (n = 2) immediately performed at above criterion levels (mean 92.5%) and were killed to serve as controls for histological analysis. In contrast, inoculated animals varied in their capacity to discriminate between air and the odor(s) to which they were trained, even though they sampled the stimulus, and in other ways carried out the task in a manner indistinguishable from untreated mice. One of the inoculated mice performed at criterion during the first post-inoculation testing session (96%); it had been trained to respond to either vanillin or propionic acid. In comparison, three mice performed at chance levels (mean 49.5%) as compared with an average pre-inoculation performance of 92.35%; two of them had been trained to respond to the odorant propyl acetate and one was trained to respond to either vanillin or propionic acid. Finally, two mice were only slightly hyposmic to their training odorant with an average performance of 77% correct detection, as compared with an average pre-inoculation level of 90.03%; they had been trained to discriminate propanol. With subsequent testing the two mice with reduced performance to the training odorant (propanol) and one mouse that was initially anosmic to its training odorant (propyl acetate) performed at or above criterion. Of the three animals that achieved criterion performance following additional testing, the two mice trained to discriminate propanol versus air did so on the second day of testing (mean 97%), whereas the other mouse, trained to discriminate propyl acetate versus air, required 3 days (94%).

With respect to the observed improvement in performance, the error patterns of the recovering mice are instructive. For the two animals with an initially reduced performance to their training odorant (propanol), the errors on the first day of testing were ones of commission rather then omission. That is, on average these animals responded appropriately to 96% of the odor trials, while responding inappropriately to 42.5% of the air stimuli (performance on air trials improved over the course of the 10 blocks of testing). On the second day of testing, both animals reached criterion performance, responding to odor and withholding response to air trials. In contrast, the animal initially anosmic to its training odorant withheld responding to both air and odorant trials. In short, as might be expected from a highly trained animal anosmic to its training odorant, the mouse responded to all stimuli as if they were air trials. On the second day of testing, however, the animal's error pattern shifted, correctly responding to 96% of the odor trials, but responding inappropriately to 73% of air trials. On day 3 of testing, appropriate responding to air trials rose to 88%, over the course of 10 blocks, in conjunction with a high level of performance on odor trials. These data suggest that the animals that recovered criterion performance are learning to track either a change in odorant quality and/or intensity (relative to the training stimulus) during the testing period. Following achievement of criterion performance, the animals were killed for histological analysis.

The remaining two mice that were anosmic to their training odorant(s) on the first day of testing (one trained to discriminate propyl acetate versus air and one trained to respond to both vanillin and propionic acid) continued to perform at chance levels. As might be expected from an anosmic animal that has had substantial overtraining on a go, no-go paradigm (i.e. a highly trained animal), these mice withheld responding to all stimuli (i.e. they responded to stimulus delivery as if all stimuli were air trials) for 2 days of testing (400 trials), after which they refused to initiate further trials. (It is worth noting that these animals received no reinforcement for 400 stimulus presentations.) At this point the animal anosmic to propyl acetate was perfused for histological analysis.

In an effort to determine whether an observed anosmia could be overcome by retraining, the mouse originally trained to respond to either vanillin or propionic acid was retrained as if it were a naive animal (i.e. it was retrained step-by-step from the initial stages of cup lick training through trial initiating and discrimination training with its original odors, namely, vanillin and propionic acid). This animal was chosen for retraining because of the known dichotomy between olfactory and trigeminal sensitivity to these odorants. Following retraining and completion of 1000 trials of the discrimination task, the mouse originally trained to respond to either vanillin or propionic acid still performed at chance levels (51.7%). In contrast to its behavior prior to retraining, the animal in these tests responded to all trials (either of the two odorants or air) as if they were odorant presentation trials (i.e. the animal licked at the cup). In other words, retraining did not re-establish stimulus control of the odorants over the animal's response behavior. The mouse merely learned a beam-break cup licking shuttling behavior. Thus, it would appear that the previously observed lack of response to the training odorants was unrelated to some non-chemosensory sequelae of the infection. Rather, it is our interpretation that the animal treated all trials during the initial post-inoculation testing as if there were no odorant stimuli presented and therefore withheld responding, as dictated by training.

The contrast in behavioral capacity among the animals was compared with the anatomical extent of change in the olfactory epithelium and bulb. The accompanying paper describes in detail the severity, timing and widespread extent of the damage to the bulb by comparison with the relatively mild changes in the epithelium of both food-restricted and ad libitum fed mice (Schwob et al., 2001). The anatomical observations in the behaviorally trained mice that are the subject of the present work are entirely consistent with our other findings (Schwob et al., 2001). Thus, the olfactory epithelium in the behaviorally trained animals is much less severely affected by virus inoculation than is the olfactory bulb. All areas of the olfactory epithelium are characterized by a population of neurons as numerous as in controls in hematoxylin and eosin stained sections. Specifically, none of the epithelium is rendered aneuronal by the infection (data not shown) (Schwob et al., 2001). This stands in stark contrast to forms of toxic lesion, such as zinc sulfate irrigation or methyl bromide exposure, which cause substantial areas of lesioned olfactory epithelium to be replaced by respiratory epithelium as a consequence of total or near total destruction of olfactory basal cells (Matulionis, 1975, 1976; Harding et al., 1978; Burd, 1993; Schwob et al., 1995). However, the neuronal population is altered somewhat from controls; as in the animals that were the subject of the accompanying investigation (Schwob et al., 2001), immature, GAP-43 stained neurons were more numerous and mature, while OMP-positive neurons were fewer in the inoculated behavioral animals as compared with controls (data not shown). The increased prevalence of immature neurons suggests, and the companion investigation demonstrates (Schwob et al., 2001), that neuronal proliferation is increased in the inoculated animals as compared with controls. Hence, neuronal turnover is accelerated. As the epithelial changes parallel the damage to and loss of cells from the bulb (Schwob et al., 2001), they are most likely not a direct effect of the virus on the epithelium, but a reflection of the bulb lesion (Schwob et al., 1992).

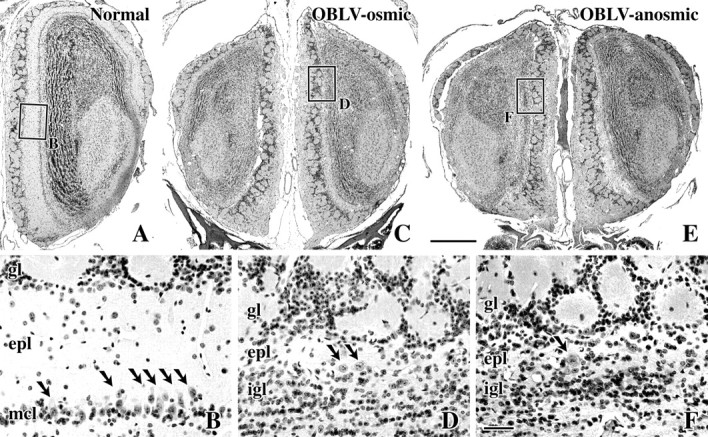

The bulbs of the mice persistently anosmic to their training odorants (MV130 and MV135) and those of the three infected animals that regained criterion performance after an initial period of compromise (MV129, MV132 and MV133) were severely disrupted by comparison with controls (Figure 2). The bulbs of the affected mice were smaller than normal overall and the thickness of the external plexiform layer was markedly reduced in these animals and even obliterated in much of the circumference of the bulb (Figure 2). In contrast, the mouse that achieved criterion performance on the first day of testing after the recovery period (MV136) was minimally affected by inoculation; the animal did not demonstrate the systemic symptoms associated with infection to the same extent as the other animals, i.e. the mouse did not appear sick in the period immediately following inoculation. The bulbs of this mouse showed no obvious evidence of damage, suggesting that the inoculum was insufficient, presumably for technical reasons, to lead to the frank encephalitis and severe damage to the bulb that is usually seen following an adequate inoculum. As a consequence, we draw a distinction between the severely affected, osmic animals and this one for the purposes of anatomical analysis.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the structure of the bulb in normal and OBLV-inoculated animals trained on the air versus odor discrimination task. (A, B) Olfactory bulb of normal mouse MV131 who retained the task following the 1 month rest period. Note the precise lamination of the bulb and numerous mitral cells, a few of which are indicated by the arrows. (C, D) Bulbs from virus-infected mouse MV132 who initially performed poorly after lesion, but soon reached the pre-lesion performance. The external plexiform layer (epl) is scant and only a very few mitral cells remain; only two, which are indicated by arrows, are evident in this high magnification field (D). (E, F) Bulbs from MV130 that was incapable of suprathreshold detection after recovery from inoculation. The bulbs are not markedly more affected than in the osmic animal and some mitral cells have survived in this case; one in this field is indicated by the arrow. Scale bar in (E), 500 μm, also applies to (A) and (C); in (F), 50 μm, also applies to (B) and (D).

The direct comparison of bulb size between the persistently anosmic mice and the severely affected, osmic animals indicates that both groups were affected to roughly the same degree (bulb volume was 25.5 ± 1.8 versus 24.7 ± 2.0% of normal, for the two anosmic mice and the three severely affected but osmic animals, respectively). In addition, there was also a modest degree of neuronal loss in the piriform cortex similar to that illustrated in the accompanying paper (Schwob, 2001), which was largely confined to anterior piriform cortex in the area that receives a heavy projection from the LOT (Schwob and Price, 1984) and seemingly spared posterior piriform cortex.

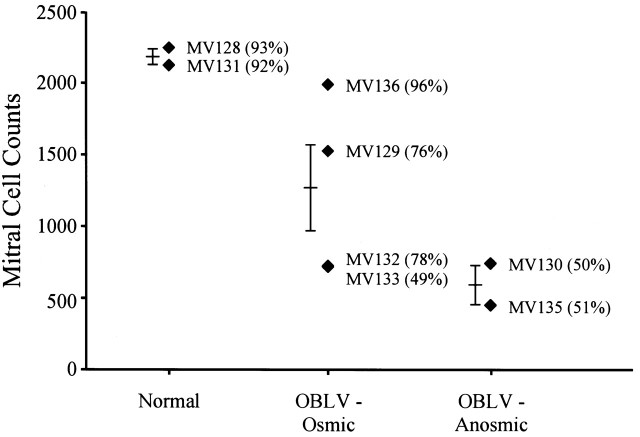

Counts of mitral cell profiles indicated that mitral cell numbers were reduced in virus-inoculated animals capable of detecting their training odorant (57% of normal when averaged across all four inoculated but osmic animals) and even more severely reduced in persistently anosmic ones (28% of normal) (Figure 3). It is important to note that some mitral cells were spared in the anosmic animals (Figure 2). The difference in mitral cell number approached statistical significance across the three behavioral groups (F = 5.17, P = 0.06, 2 d.f.) and would reach significance if the mouse that achieved criterion on the first testing day (MV136) and was minimally sick following infection was eliminated from the statistical comparison. The mitral cell counts and the bulb volumes in the three mice that were eventually able to detect the training odorants but did not reach criterion until the second or third day of testing were much lower than in MV136, which performed at criterion on the first test day. A further comparison of the behavioral and anatomical data on an animal-by-animal basis is informative. The mitral cell counts of two of the mice that eventually reached criterion overlapped the values recorded for the mice that were persistently anosmic to the training odorant(s). Included in those two recovered mice with very low mitral cell numbers is MV133, which did not achieve criterion performance until the third day of testing (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The number of mitral cells that survived infection correlates weakly with the behavioral capacity of the inoculated mice. Raw uncorrected counts of mitral cell profiles summed across the five sampled sections are plotted for each of the three behaviorally defined groups: normal; OBLV-inoculated but able to perform the air—odor discrimination at the pre-infection criterion level (OBLV-Osmic) either immediately on re-initiating testing 1 month after infection or shortly thereafter; OBLV-inoculated and unable to recover their performance of the air—odor discrimination to the pre-infection criterion level (OBLV-Anosmic). The numbers in parentheses record the performance during the first post-lesion testing session. MV129 and 132 recovered to criterion level at the second testing session. MV133 recovered to criterion level at the third. Odorants were: MV130 and 131, propyl acetate; MV128, 129, 132 and 133, 2-propanol; MV135 and 136, vanillin and propionic acid.

Given the overlap in mitral cell counts among some osmic and anosmic animals, the effect of the virus on the trigeminal system was analyzed in an effort to explain the differences in the behavioral capacity across the group of infected mice. Activation of trigeminal fibers presumably subserves the detection of chemical stimuli following nerve transection (Henton et al., 1966, 1969). Likewise, some human anosmics detect the presence of odorants without any preservation of quality coding (Doty, 1975; Doty et al., 1978) and/or distinguish pungent odorants, such as ammonia and vinegar, from non-pungent ones, such as phenethyl alcohol, in the context of an odorant identification task (Hornung et al., 1994; Kurtz et al., 1999). The residual sensory capacity of otherwise anosmic patients is also most likely mediated by the trigeminal innervation of the nose. Intranasal inoculation with MHV JHM infects trigeminal axons and can be retrogradely transported to the trigeminal ganglion (Perlman et al., 1989). Accordingly, we assessed the distribution of substance P-containing trigeminal fibers in the olfactory mucosa of normal mice, infected but osmic mice (i.e. capable of detecting their training odorants) and infected and persistently anosmic mice (i.e. incapable of detecting their training odorants).

In normal mice, small fascicles of substance P-stained fibers are scattered along the basal lamina (Figure 4). Occasionally a stained axon is observed as it ascends through the epithelium to the apical surface. Our observations in normals are similar to previously published descriptions of the distribution of substance P fibers in the nasal mucosa (Finger et al., 1990). Viral infection that produced persistent anosmia severely depleted the number of substance P fibers, including both the fascicles at the basal lamina and the fibers that traverse the width of the epithelium, and markedly reduced their distribution along the tangential plane of the epithelium as compared with normal (Figures 4 and 5). The number and distribution of stained fibers was also reduced in the infected, osmic animals as compared with normal, but was less severely affected than in the cases where viral inoculation produced anosmia (Figures 4 and 5). Indeed, the osmic mouse (MV132, trained to 2-propanol) and the anosmic mouse (MV130, trained to propyl acetate) illustrated here retained a nearly equivalent number of mitral cell profiles (33.7 and 34.6% of the profile counts in normals, respectively) (Figure 3), but differ in the degree to which substance P fibers were spared (88.2 and 34.3% of normal, respectively) (Figures 4, 5). Thus, the difference in post-infection performance between these two animals correlates better with the extent of substance P-stained fibers than with counts of mitral cell profiles. However, that the animals were trained to different odorants may also interact in some fashion with the status of the bulb and epithelium to influence detection behavior.

Figure 4.

Substance P staining demonstrates differences in the extent of trigeminal fibers across the three behaviorally defined groups. In all three cases, the labeling is concentrated at the basal lamina. (A, B) The density of labeling is roughly equivalent in the normal and OBLV-inoculated, osmic mouse. The arrow in (A) indicates a fiber that ascends through the epithelium toward its apical surface. (C) Substance P-labeled fibers are much reduced in the OBLV-inoculated, anosmic mouse. Scale bar in (C) 50 μm, also applies to (A) and (B).

Discussion

The results presented here demonstrate that infection with an adapted strain of MHV, termed MHV OBLV, produces anosmia to the training odorants in a subset of intranasally inoculated mice. Thus, viral infection is one of the few experimental manipulations that can cause persistent anosmia. The others are complete surgical ablation of the olfactory bulb and irreversible destruction of the periphery by zinc sulfate in a limited subset of irrigated mice (Harding et al., 1978). In the case of direct damage to the periphery, it has been well established that odor detection or normal food finding behavior survives as long as a small population of sensory neurons is spared (Slotnick and Gutman, 1977; Harding et al., 1978; Hastings, 1990; Hastings et al., 1991). As little as 5% of the normal complement of sensory neurons in the epithelium can support normal or near normal threshold sensitivity (Youngentob et al., 1997). Likewise, animals with relatively small remnants of one olfactory bulb can perform a variety of detection and discrimination tasks (Slotnick et al., 1997; Lu and Slotnick, 1998). In contrast, the manipulation performed here leaves much of the bulb intact and destroys none of the olfactory epithelium permanently. Thus, the comparison of the anatomical and behavioral results after viral inoculation presents several paradoxes. First, as demonstrated fully in the companion paper (Schwob et al., 2001), the olfactory epithelium is not damaged to an extent that can explain the persistent anosmia, given the aforementioned observations on behavioral capacity following direct toxic lesions of the epithelium (Slotnick and Gutman, 1977; Youngentob et al., 1997). Rather, the changes in the epithelium are largely a consequence of, and vary with, the severity of damage to the bulb. Nonetheless, a large population of OMP-positive neurons is maintained even in the anosmic animals and the proportion of mature to immature neurons is greater than is observed in the epithelium of bulbectomized animals (Monti Graziadei, 1983; Schwob et al., 1992). Second, on the order of 25% or more of mitral cells persist in the anosmic animals, which also appears inconsistent with the studies cited that utilize partial bulb ablation. Third, the number of mitral cells in osmic animals overlaps the range of cell number observed in anosmic animals.

The paradoxes may exist because there are more subtle difference(s) in the structure of the bulb between mice anosmic to their training odorants and mice capable of detecting their training odorants that cannot be appreciated at the level of analysis presented here. For example, anosmia may be due to complete or near complete disconnection of the surviving mitral cells from the olfactory epithelium. Conversely, odorant detection by previously inoculated mice may reflect the preservation of synaptic input from olfactory axons onto some of the remaining mitral cells. Other data suggest that few if any mitral cells retain dendrites that extend into the glomerular layer after infection and damage under the inoculation conditions used here (Schwob et al., 2001). However, we cannot currently conclude that all surviving mitral cells are disconnected from the epithelium in the anosmic animals because the extent of disconnection from the periphery could not be precisely quantified in these experiments. Because the existing data suggest that any differences in mitral cell connectivity between anosmic and osmic animals may be small, it is likely that experimental variability would make it difficult if not impossible to test the hypothesis that differences in number of connected mitral and tufted cells are responsible for the behavioral differences between osmic and anosmic animals, in the light of the published demonstrations that function is preserved with very small fragments of the bulb (Slotnick et al., 1997; Lu and Slotnick, 1998). As a consequence, we cannot discount the possibility that differential sparing of inputs from sensory neurons onto mitral cells in osmic versus anosmic animals, whereby the inputs are insufficient to subserve detection in the anosmic mice, may be responsible for the observed variation in behavioral capacity.

Alternatively, intranasal stimulation of the trigeminal system may support the capacity to detect odorant stimuli in the osmic animals either in part or in total and the reduction in magnitude of the substance P innervation of the mucosa in the anosmic animals may explain their behavioral deficit. The current data are insufficient to assign the anatomical locus for the sensory deficiency in the anosmic animals with assurance. However, the comparisons of individual osmic versus anosmic animals, specifically the greater depletion of substance P-labeled fibers in the anosmic animals and the roughly equivalent number of mitral cells, suggest that the extent of damage to the trigeminal system may be the factor determining whether odorant detection is preserved, despite the massive reduction in the number of mitral cells and the apparent disconnection of many of the rest.

Conclusion

The functional manifestation of olfactory disease induced by a given virus likely depends on a number of factors: its ability to infect specific populations of cells within the olfactory system, its affect on other chemosensory structures and the transport of the virus to more central structures. The OBLV model provides a potential means of assessing the functional consequences (and thus its potential involvement in human disease) of infection with a virus that may destroy parts of the chemosensory apparatus beyond the olfactory epithelium, including CNS tissue, such as the olfactory bulb and piriform cortex, and the trigeminal ganglion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Michael Buchmeier for his kind gift of the MHV-OBLV viral stock. This work was supported by NIH grants P01 DC 00220 (J.E.S. and S.L.Y.) and R01 DC03904 (S.L.Y.).

References

- Barthold, S.W. (1988) Olfactory neural pathway in mouse hepatitis virus nasoencephalitis Acta Neuropathol., 76,502 -506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd, G.D. (1993) Morphological study of the effects of intranasal zinc sulfate irrigation on the mouse olfactory epithelium and olfactory bulb Microsc. Res. Technol.,24 , 195-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty, R.L. (1975) Intranasal trigeminal detection of chemical vapors by humans Physiol. Behav.,14 , 855-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty, R.L., Brugger, W.E., Jurs, P.C., Orndorff, M.A., Snyder, P.J. and Lowery, L.D. (1978) Intranasal trigeminal stimulation from odorous volatiles: psychometric responses from anosmic and normal humans Physiol. Behav., 20,175 -185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, A.S. and Kaslow, R.A. (1997)Viral Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control , 4th edn. Plenum Publishing, New York, NY.

- Finger, T.E., St Jeor, V.L., Kinnamon, J.C. and Silver, W.L. (1990) Ultrastructure of substance P and CGRP-immunoreactive nerve fibers in the nasal epithelium of rodentsJ. Comp. Neurol. , 294,293 -305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, T.M., Escarmis, C. and Buchmeier, M.J. (1991) Alteration of the pH dependence of coronavirus-induced cell fusion: effect of mutations in the spike glycoprotein J. Virol., 65,1916 -1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, J.W., Getchell, T.V. and Margolis, F.L. (1978) Denervation of the primary olfactory pathway in mice. V. Long-term effect of intranasal ZnSO4 irrigation on behavior, biochemistry and morphology Brain Res.,140 , 271-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, L. (1990) Sensory neurotoxicology: use of the olfactory system in the assessment of toxicity Neurotoxicol. Teratol.,12 , 455-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, L., Miller, M.L., Minnema, D.J., Evans, J. and Radike, M. (1991) Effects of methyl bromide on the rat olfactory system Chem. Senses, 16,43 -55. [Google Scholar]

- Henton W.W., Smith J.C. and Tucker D. (1966) Odor discrimination in pigeonsScience , 153,1138 -1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henton W.W., Smith J.C. and Tucker D. (1969) Odor discrimination in pigeons following section of the olfactory nerves Comp. Physiol. Psychol.,69 , 317-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, D.E., Kurtz, D.B. and Youngentob, S.L. (1994) Can anosmic patients separate trigeminal and non-trigeminal stimulants? In Kurihara, K., Sukuki, N. and Ogawa H. (eds), Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium of Olfaction and Taste. Springer-Verlag, Tokyo, p.635 .

- Hurtt, M.E., Thomas, D.A., Working, P.K., Monticello, T.M. and Morgan, K.T. (1988) Degeneration and regeneration of the olfactory epithelium following inhalation exposure to methyl bromide: pathology, cell kinetics, and olfactory function Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 94,311 -328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, D., White, T.L., Hornung, D.E. and Belknap, E. (1999) What a tangled web we weave: discriminating between malingering and anosmia Chem. Senses,24 , 697-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, H.E., Reed, S.E. and Tyrrell, D.A. (1980) Isolation of rhinoviruses and coronaviruses from 38 colds in adults J. Med. Virol., 5,221 -229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.-C.M. and Slotnick, B.M. (1998) Olfaction in rats with extensive lesions of the olfactory bulbs: implications for odor coding Neuroscience,84 , 849-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matulionis, D.H. (1975) Ultrastructural study of mouse olfactory epithelium following destruction by ZnSO4 and its subsequent regeneration Am. J. Anat.,142 , 67-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matulionis, D.H. (1976) Light and electron microscopic study of the degeneration and early regeneration of olfactory epithelium in the mouse Am. J. Anat.,145 , 79-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti Graziadei, G.A. (1983) Experimental studies on the olfactory marker protein. III. The olfactory marker protein in the olfactory neuro-epithelium lacking connections with the forebrainBrain Res. , 262,303 -8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, D.T., Jafek, B.W., Eller, P.M. and Rowley, J.C. (1992) Ultrastructural histopathology of human olfactory dysfunction Microsc. Res. Technol.,23 , 103-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott, A.E. and Leopold, D.A. (1991) Disorders in taste and smell Med. Clin. North Am.,75 , 1321-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman, S., Jacobsen, G. and Afifi, A. (1989) Spread of a neurotropic murine coronavirus into the CNS via the trigeminal and olfactory nerves Virology,170 , 556-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, E.F., Snyder, E.Y. and Cepko, C.L. (1990) Establishment and characterization of multipotent neural cell lines using retrovirus vector-mediated oncogene transferJ. Neurobiol. , 21,356 -375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob, J.E. and Price, J.L. (1984) The development of axonal connections in the central olfactory system of rats J. Comp. Neurol., 223,177 -202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob, J.E., Mieleszkow Szumowski, K.E. and Stasky, A. (1992) Olfactory sensory neurons are trophically dependent on the olfactory bulb for their prolonged survival J. Neurosci., 12,3896 -3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob, J.E., Youngentob, S.L. and Mezza, R.C. (1995) The reconstitution of the olfactory epithelium after methyl bromide induced lesions J. Comp. Neurol.,359 , 15-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob, J.E., Saha, S., Youngentob, S.L. and Jubelt, B. (2001) Intranasal inoculation with the olfactory bulb line variant of mouse hepatitis virus causes extensive destruction of the olfactory bulb and accelerated turnover of neurons in the olfactory epithelium of mice Chem. Senses, 26, (accompanying paper TF8-99). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver, W.L. and Moulton, D.G. (1982) Chemosensitivity of the rat nasal trugeminal receptorsPhysiol. Behav. , 28,927 -931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick, B. (1984) Olfactory stimulus control in the rat Chem. Senses,9 , 157-165. [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick, B.M. and Gutman, L.A. (1977) Evaluation of intranasal zinc sulfate treatment on olfactory discrimination in rats J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol.,91 , 942-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick, B.M., Bell, G.A., Panhuber, H. and Laing, D.G. (1997) Detection and discrimination of propionic acid after removal of its 2-DG identified major focus in the olfactory bulb: a psychophysical analysis Brain Res.,762 , 89-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop, W.G. (1995) Viruses and the olfactory system In Doty, R.L. (ed.), Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY, pp.367 -393.

- Valenti, W.M. (1984) Nosocomial viral infections In Bellshe, R.B. (ed.), Textbook of Human Virology. PSG Publishing, Littleton, MA, pp.231 -266.

- Yamagishi, M., Hasegawa, S. and Nakano, Y. (1988) Examination and classification of human olfactory mucosa in patients with clinical olfactory disturbances Arch. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 245,316 -320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi, M., Nakamura, H., Suzuki, S., Hasegawa, S. and Nakano, Y. (1990) Immunohistochemical examination of olfactory mucosa in patients with olfactory disturbance Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 99,205 -210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi, M., Fujiwara, M. and Nakamura, H. (1994) Olfactory mucosal findings and clinical course in patients with olfactory disorders following upper respiratory viral infection Rhinology, 32,113 -118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngentob, S.L. and Margolis, F.L. (1999) OMP gene deletion causes an elevation in behavioral threshold sensitivity NeuroReport,10 , 15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngentob, S.L., Markert, L.M., Mozell, M.M. and Hornung, D.E. (1990) A method for establishing a five odorant identification confusion matrix in rats Physiol. Behav., 47,1053 -1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngentob, S.L., Hornung, D.E. and Mozell, M.M. (1991) Determination of carbon dioxide detection thresholds in trained rats Physiol. Behav.,49 , 21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngentob, S.L., Markert, L.M., Hill, T.W., Matyas, E.P. and Mozell, M.M. (1991) Odorant identification in rats: an update Physiol. Behav.,49 , 1293-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngentob, S.L., Schwob, J.E., Sheehe, P.R. and Youngentob, L.M. (1997) Odorant threshold following methyl bromide-induced lesions of the olfactory epitheliumPhysiol. Behav. , 62,1241 -1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]