Abstract

New strategies to prevent and treat influenza virus infections are urgently needed. A recently discovered class of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) neutralizing an unprecedented spectrum of influenza virus subtypes may have the potential for future use in humans. Here, we assess the efficacies of CR6261, which is representative of this novel class of mAbs, and oseltamivir in mice. We show that a single injection with 15 mg/kg CR6261 outperforms a 5-day course of treatment with oseltamivir (10 mg/kg/day) with respect to both prophylaxis and treatment of lethal H5N1 and H1N1 infections. These results justify further preclinical evaluation of broadly neutralizing mAbs against influenza virus for the prevention and treatment of influenza virus infections

Influenza viruses continue to cause significant morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. Although vaccination is the primary means of influenza control, vaccines have suboptimal efficacy in the highest risk groups—young children, elderly persons, and immunocompromised individuals [2]. Furthermore, because of the rapid evolution of influenza viruses, influenza vaccines are typically effective only against strains closely related to the one(s) on which they are based. This fact, together with the unpredictable nature of the next pandemic strain, means that it is unlikely that an effective vaccine will be available in the early stages of a pandemic

For the treatment and/or prophylaxis of influenza virus infections, only 2 classes of drugs are currently available: the adamantanes and the neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors. The adamantanes (amantadine and rimantadine) are associated with toxicity and with the rapid emergence of drug-resistant strains [3]. Compared with the adamantanes, the 2 licensed NA inhibitors—zanamivir (Relenza) and oseltamivir (Tamiflu)—are associated with little toxicity and are less prone to select for resistant viruses [3]. Nevertheless, the emergence of resistance after oseltamivir treatment has been reported ([4] and references therein). Furthermore, oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 viruses are now circulating on all major continents [5]. Although at present these viruses are susceptible to zanamivir, the resulting increased use of zanamivir monotherapy may well lead to the development of resistance [6]

Consequently, there is an urgent need for the development of new treatments, both prophylactic and therapeutic. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are attractive biologic drugs given their exquisite specificity and low toxicity. The development of mAbs for prophylaxis and treatment of influenza has been inhibited by the lack of candidates with broad neutralizing activity resulting from the virus’s tolerance for genetic changes in its immunodominant epitopes. However, a recently discovered class of mAbs that are able to neutralize an unprecedented spectrum of influenza virus subtypes by binding to a highly conserved region of the membrane-proximal stem of the viral hemagglutinin holds promise as a future intervention for both seasonal and pandemic influenza [7, 8]

Here, we compare the prophylactic and therapeutic efficacies of the mAb CR6261, which represents this novel class of anti–influenza virus mAbs, with those of the leading antiviral drug, oseltamivir, in mouse models of lethal H5N1 and H1N1 infection

MethodsThe human mAb CR6261 has been described elsewhere [8]. An irrelevant isotype-matched antibody, CR3014 [9], was used as a control. Both antibodies were produced in PER.C6 cells (Crucell Holland). Oseltamivir (Tamiflu; Hoffmann-La Roche) was obtained from a local pharmacy

The H5N1 strain A/HongKong/156/97 was originally isolated from a 3-year-old child with respiratory disease [10]. The virus was passaged twice in MDCK cells. The stock (8.1 log10 median tissue culture infective dose [TCID50]/mL) used to infect mice was propagated once in embryonated eggs. The H1N1 strain A/WSN/33 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (VR-219). The stock (8.5 log10 TCID50/mL) used to infect mice was propagated once in embryonated eggs

All experiments were approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Central Veterinary Institute before commencement, in accordance with Dutch law. Female, 7-week-old, specific pathogen–free BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories) were inoculated intranasally with 25 times the median lethal dose of A/HongKong/156/97 (4.5 log10 TCID50) or A/WSN/33 (6.6 log10 TCID50), and survival, weight loss, and clinical signs were monitored until 21 days after infection. Clinical signs were scored with a scoring system (0, no clinical signs; 1, rough coat; 2, rough coat, less reactive, and passive during handling; 3, rough coat, rolled up, labored breathing, and passive during handling; 4, rough coat, rolled up, labored breathing, and unresponsive). Animals with a score of 4 were euthanized. In the prophylactic experiments, 15 mg/kg CR6261 was administered intravenously 1 day before challenge, and 10 mg/kg oseltamivir was administered per os daily for 5 days starting 1 day before challenge. In the therapeutic experiments, CR6261 and oseltamivir were administered as described above on day 4 and for 5 days starting on day 4 after infection, respectively

Survival times after viral challenge were analyzed using the log-rank test, and survival proportions were analyzed using the Fisher exact test. Change in body weight was analyzed using an area under the curve (AUC) analysis in which the last observed body weight was carried forward if a mouse died or was euthanized during the experiment. The weight per mouse on day 0 was used as baseline, and weight change was determined relative to baseline. The net AUCs were compared by 1-way analysis of variance. Comparisons to the control group were performed by post-hoc testing with Dunnett’s adjustment for multiple comparisons. Clinical scores were analyzed using the GENMOD procedure (SAS software) to fit a model to repeated measures, with mice as the subject and the data measured on an ordinal scale. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1; SAS Institute) and SPSS (version 15.0; SPSS) software. The statistical significance level was set at α=.05

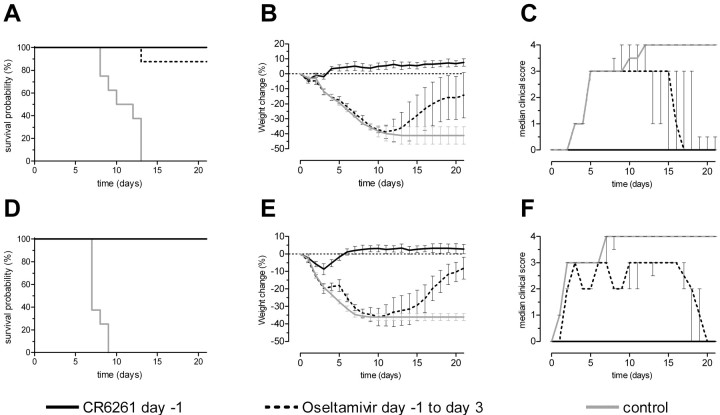

Results Figure 1 shows the prophylactic efficacies of the mAb CR6261 and oseltamivir against lethal challenge with A/HongKong/156/97(H5N1) and A/WSN/33(H1N1). All animals that received CR6261 survived challenge with both viruses without showing any signs of disease, except for a decline in body weight of ∼9% during the first 3 days after challenge with A/WSN/33 (Figure 1E). In contrast, all control animals rapidly showed signs of disease, lost weight, and either died of the infection or were euthanized within 2 weeks after either challenge. All but one of the oseltamivir-treated mice survived challenge with A/HongKong/156/97 (Figure 1A). However, in contrast to the CR6261-treated mice, these animals lost weight comparable to the control group until 11 days after infection, when they started to regain weight (P<.001) (Figure 1B). Furthermore, all oseltamivir-treated mice showed signs of illness beginning on day 5 after infection and started to recover on day 15 (Figure 1C). Similarly, treatment with oseltamivir prevented death but not weight loss and signs of disease on challenge with A/WSN/33. Mice treated with oseltamivir lost weight similarly to the control group during the first 10 days after challenge, after which they started to regain weight (Figure 1E), and this loss was greater than that of the group treated with CR6261 (P<.001). Signs of disease were observed in individual animals between days 2 and 19 after challenge, and median clinical scores differed significantly from those of the CR6261-treated group between days 2 and 17 (P⩽.032) (Figure 1F). The alternating median clinical scores (between 2 and 3) of this group is likely explained by subjectivity in the assessment of clinical scores by different observers. Taken together, these data indicate that prophylactic administration of a single intravenous injection with 15 mg/kg CR6261 is more effective against lethal H5N1 and H1N1 challenge than a 5-day course of treatment with oseltamivir at 10 mg/kg/day

Figure 1.

Prophylactic efficacy of the monoclonal antibody CR6261 and oseltamivir against lethal challenge with 25 times the median lethal dose of either A/HongKong/156/97 (top panels) or A/WSN/33 (bottom panels). Groups of 8 mice received either a single intravenous injection of 15 mg/kg CR6261 one day before challenge or 10 mg/kg oseltamivir per os for 5 days starting 1 day before challenge. As controls, groups of 8 mice received an irrelevant isotype-matched control monoclonal antibody (15 mg/kg). Mice were monitored for 21 days or until death. A and D, Kaplan-Meier survival probability curves. B and E, Mean change in body weight per group, expressed as the percentage of baseline body weight. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. C and F, Median clinical scores per group, with interquartile ranges

Figure 2 shows the therapeutic efficacies of mAb CR6261 and oseltamivir against lethal challenge with A/HongKong/156/97(H5N1) and A/WSN/33(H1N1). Treatment with CR6261 four days after challenge with A/HongKong/156/97 did not prevent initial weight loss and signs of disease. However, it did completely prevent mortality, and animals had regained their initial body weight by the end of the experiment (Figure 2A and 2B). Accordingly, these mice started to recover on day 12, and none showed any signs of disease from day 19 onward. In contrast to the 100% survival in the group treated with CR6261, only 25% of the mice treated with oseltamivir survived infection with A/HongKong/156/97 (P=.007). These mice lost significantly more weight than did those in the group treated with CR6261 (P=.001), and median clinical scores were significantly higher from day 9 until the end of the study on day 21 (P⩽.037). The 2 survivors showed respiratory distress until days 19 and 21 and had not regained their initial body weight at the end of the study (−2.4% and −24.9%)

Figure 2.

Therapeutic efficacy of the monoclonal antibody CR6261 and oseltamivir against lethal challenge with 25 times the median lethal dose of either A/HongKong/156/97 (top panels) or A/WSN/33 (bottom panels). Groups of 8 mice received either a single intravenous injection of 15 mg/kg CR6261 on day 4 after infection or 10 mg/kg oseltamivir per os for 5 days from day 4 after infection onward. Mice were monitored for 21 days or until death. A and D, Kaplan-Meier survival probability curves. B and E, Mean change in body weight per group, expressed as the percentage of baseline body weight. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. C and F, Median clinical scores per group, with interquartile ranges

Although prophylactic administration of CR6261 fully protected mice against lethality from A/WSN/33 challenge, only 3 of 8 animals survived when CR6261 was given 4 days after challenge (Figure 2D). Nevertheless, survival time in this group was significantly longer than that in the group treated with oseltamivir, in which all animals died within 10 days after challenge (P=.031). However, there was no significant difference in relative weight loss between both groups (P=.592), and clinical scores differed significantly only on days 1 and 10 (P=.021 and P=.034, respectively) (Figure 2E and 2F)

DiscussionWe have demonstrated that a single intravenous injection with 15 mg/kg CR6261 outperforms a 5-day course of treatment with oseltamivir at 10 mg/kg/day with respect to both prophylaxis against and treatment of lethal H5N1 and H1N1 infections in mice. These encouraging results in these highly stringent models justify further preclinical evaluation of CR6261 as alternative strategy for the control of influenza. The 15 mg/kg dose of CR6261 used in this study was based on previous experiments in mice [8], but further studies are needed to assess the minimal plasma concentrations of this mAb necessary for effective prophylaxis and treatment. A 5-day course of treatment with oseltamivir at 5 mg/kg/day has previously been shown to be protective against lethal challenge of mice with A/WSN/33 [11], whereas treatments with doses as low as 1 mg/kg/day (and even 0.1 mg/kg/day) have been shown to protect mice against lethal challenge with A/HongKong/156/97 [12, 13]. In these latter studies, oseltamivir was administered in a twice-a-day regimen, whereas we used a once-a-day regimen. However, when comparing the efficacy of 1 daily administration of 10 mg/kg oseltamivir with that of 2 daily administrations of 5 mg/kg against lethal A/HongKong/156/97 infection, we found no difference (data not shown). This result is in line with previously reported data showing no significant difference in the efficacy of oseltamivir at 5 mg/kg/day against lethal A/WSN/33 infection of mice when given as a single dose or in 2 doses 12 h apart [11]

Although therapeutic administration of CR6261 completely prevented death due to A/HongKong/156/97, it only partially prevented mortality due to A/WSN/33. This difference is likely explained by the fact that onset of disease and progression to death were more rapid after challenge with the latter virus. The median clinical scores at the moment of antibody administration (4 days after challenge) were 1 and 3 for the groups of mice challenged with A/HongKong/156 and A/WSN/33, respectively. Accordingly, the median survival time in the control group challenged with A/WSN/33 was shorter than that in the control group challenged with A/HongKong/156/97 (7 vs 10 days; P=.003). However, the fact that administration of CR6261 to mice that had already lost 24.1% of their initial body weight and that showed severe respiratory distress still partially prevented death demonstrates the fast mode of action. This feature, combined with the relatively long half-life (2–3 weeks) in humans of mAbs produced in PER.C6 cells [14], make human mAb–based passive immunotherapy a viable option for both treatment and prophylaxis of disease due to influenza virus infection, provided that comparable efficacies can be obtained in humans with economically feasible doses of antibody

Acknowledgment

We thank Els de Boer-Luijtze for excellent technical assistance

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: W.K., M.H.K., J.P.J.B, G.J.W., R.H.E.F., and J.G. are employees of Crucell Holland BV. L.A.H.M.C reports no potential conflicts

Presented in part: World Vaccine Congress 2009, Washington, 20–23 April 2009

Financial support: Crucell Holland BV

PER.C6 is a registered trademark owned by Crucell Holland BV

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Fact sheet 211: influenza. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 55:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moscona A. Medical management of influenza infection. Annu Rev Med. 59:397–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.061506.213121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephenson I, Democratis J, Lackenby A, et al. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance after oseltamivir treatment of acute influenza A and B in children. Clin Infect Dis. 48:389-96. doi: 10.1086/596311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Influenza A(H1N1) virus resistance to oseltamivir—2008/2009 influenza season. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 6.Poland GA, Jacobson RM, Ovsyannikova IG. Influenza virus resistance to antiviral agents: a plea for rational use. Clin Infect Dis. 48:1254–6. doi: 10.1086/598989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekiert DC, Bhabha G, Elsliger MA, et al. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science. 324:246–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1171491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Throsby M, van den Brink E, Jongeneelen M, et al. Heterosubtypic neutralizing monoclonal antibodies cross-protective against H5N1 and H1N1 recovered from human IgM+ memory B cells. PLoS ONE. 3:e3942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ter Meulen J, Bakker AB, van den Brink EN, et al. Human monoclonal antibody as prophylaxis for SARS coronavirus infection in ferrets. Lancet. 363:2139–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16506-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subbarao K, Klimov A, Katz J, et al. Characterization of an avian influenza A (H5N1) virus isolated from a child with a fatal respiratory illness. Science. 279:393–6. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sidwell RW, Bailey KW, Bemis PA, Wong MH, Eisenberg EJ. Influence of treatment schedule and viral challenge dose on the in vivo influenza virus-inhibitory effects of the orally administered neuraminidase inhibitor GS 4104. Antivir Chem Chemother. 10:187–93. doi: 10.1177/095632029901000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govorkova EA, Leneva IA, Goloubeva OG, Bush K, Webster RG. Comparison of efficacies of RWJ-270201, zanamivir, and oseltamivir against H5N1, H9N2, and other avian influenza viruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 45:2723–32. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.10.2723-2732.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leneva IA, Roberts N, Govorkova EA, Goloubeva OG, Webster RG. The neuraminidase inhibitor GS4104 (oseltamivir phosphate) is efficacious against A/Hong Kong/156/97 (H5N1) and A/Hong Kong/1074/99 (H9N2) influenza viruses. Antiviral Res. 48:101–15. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(00)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakker AB, Python C, Kissling CJ, et al. First administration to humans of a monoclonal antibody cocktail against rabies virus: safety, tolerability, and neutralizing activity. Vaccine. 26:5922–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]