Abstract

Recent studies showed that the circulating stress hormones, epinephrine and corticosterone/cortisol, are involved in mediating ozone-induced pulmonary effects through the activation of the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axes. Hence, we examined the role of adrenergic and glucocorticoid receptor inhibition in ozone-induced pulmonary injury and inflammation. Male 12-week old Wistar-Kyoto rats were pretreated daily for 7 days with propranolol (PROP; a non-selective β adrenergic receptor [AR] antagonist, 10 mg/kg, i.p.), mifepristone (MIFE; a glucocorticoid receptor [GR] antagonist, 30 mg/kg, s.c.), both drugs (PROP+MIFE), or vehicle controls, and then exposed to air or ozone (0.8 ppm), 4 h/d for 1 or 2 consecutive days while continuing drug treatment. Ozone exposure alone led to increased peak expiratory flow rates and enhanced pause (Penh); with greater increases by day 2. Receptors blockade minimally affected ventilation in either air- or ozone-exposed rats. Ozone exposure alone was also associated with marked increases in pulmonary vascular leakage, macrophage activation, neutrophilic inflammation and lymphopenia. Notably, PROP, MIFE and PROP+MIFE pretreatments significantly reduced ozone-induced pulmonary vascular leakage; whereas PROP or PROP+MIFE reduced neutrophilic inflammation. PROP also reduced ozone-induced increases in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) IL-6 and TNF-α proteins and/or lung Il6 and Tnfα mRNA. MIFE and PROP+MIFE pretreatments reduced ozone-induced increases in BALF N-acetyl glucosaminidase activity, and lymphopenia. We conclude that stress hormones released after ozone exposure modulate pulmonary injury and inflammatory effects through AR and GR in a receptor-specific manner. Individuals with pulmonary diseases receiving AR and GR-related therapy might experience changed sensitivity to air pollution.

Keywords: Stress response, glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, adrenergic receptor antagonist, ozone, lung injury, lung inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Ozone is a reactive secondary pollutant which oxidizes biomolecules in the respiratory tract upon inhalation (Bromberg, 2016). The accepted paradigm of ozone-induced lung injury and inflammation involves its direct interaction with lung lining components and generation of oxidized lipid and protein byproducts (Auerbach and Hernandez, 2012), which are responsible for activation of the inflammatory signaling cascade and mediating downstream effects such as lung function decrement, increased vascular permeability, and neutrophilic inflammation. These ozone-induced effects are reversible even if daily exposure continues over several days suggesting tolerance or adaptation (Miller et al., 2016a). The oxidatively-modified reactive byproducts generated locally within the lung are believed to promote local cellular effects, such as stimulating the release of cytokines and chemokines to promote recruitment of neutrophils and activation of NRF2 and NFκB pathways in the lung (Hollingsworth et al., 2007). These reactive byproducts are also thought to promote systemic effects through their release from the lung to circulation. The identity of circulating bioactive molecules and how they influence lung effects of air pollutants remains an area of interest.

Acute ozone exposure has also been shown to induce pulmonary sensory irritation and C-fiber activation. Upstream events that are involved in this response include neuron firing of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) (Gackiere et al., 2011), increases in circulating adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (Thomson et al., 2013), and cardiac changes through autonomic reflex mechanisms (Arjomandi et al., 2015; Gordon et al., 2014). These events suggest that ozone inhalation is capable of triggering a centrally-mediated neuroendocrine stress response which results in increased release of stress hormones into the systemic circulation (Kodavanti, 2016; Snow et al., 2017). Indeed, we have recently shown that circulating stress hormones such as epinephrine and cortisol/corticosterone rise rapidly after acute ozone exposure in both rodents (Bass et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2015, 2016b) and humans (Miller et al., 2016c). Subsequent ozone-induced lung global gene expression changes mimic those induced by downstream events promoted by β2 adrenergic and glucocorticoid receptor activation, further suggesting that circulating stress hormones might play a key role as mediators of pulmonary responses (Henriquez et al., 2017). The role of circulating adrenal gland-derived stress hormones in ozone-induced lung injury and inflammation in rats was further confirmed by the evidence that bilateral adrenalectomy diminished these ozone effects (Miller et al., 2016b) and associated global lung transcriptional changes (Henriquez et al., 2017).

Circulating adrenal-derived stress hormones, epinephrine and corticosterone mediate their tissue effects through adrenergic (AR; α and β) and glucocorticoid (GR) receptors. AR are widely distributed throughout the body and although epinephrine is a prototypical agonist for all types of AR, the selective activation of specific AR subtypes determines the physiological organ-specific response. β1AR are mainly expressed in the cardiac tissue and are central in maintaining cardiac output and contractility of cardiac muscle (Kurz et al., 1991), hence βAR blockers are widely used to reduce blood pressure. On the other hand, β2AR are primarily distributed in the smooth muscles of bronchi and blood vessels (Molinoff, 1984). Airway smooth muscle relaxation by β2AR agonists is a common pharmacological intervention used for bronchodilation in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Cazzola et al., 2013). Propranolol (PROP) is a non-selective βAR antagonist capable of blocking both β1AR and β2AR and, unlike epinephrine, it readily crosses the blood brain barrier (Olesen et al., 1978).

Circulating cortisol/corticosterone binds to GR that are present in virtually all cells in the body. Nuclear translocation of these receptors up-regulates a variety of genes involved in homeostatic response(s) (Oakley and Cidlowski, 2013). Non-genomic actions of glucocorticoids on GR have also been identified (Duque and Munhoz, 2016). Although the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive actions of glucocorticoids are not completely understood, potent GR agonists are commonly used to treat inflammatory conditions (Petta et al., 2016). By contrast, other studies have shown pro-inflammatory actions of GR activation (Cruz-Topete and Cidlowski, 2015). Mifepristone (MIFE) is a GR antagonist used to examine cellular effects of GR (Kakade and Kulkarni, 2014).

Based on the previous observation that circulating stress hormones are likely involved in mediating pulmonary effects of ozone (Miller et al., 2016b), the goal of this study was to examine the role of stress hormone receptors, βAR and GR in ozone-induced local lung injury and inflammation using a pharmacological approach. PROP, a non-selective βAR antagonist, was used to antagonize the activity of epinephrine while MIFE, a GR antagonist, was used to antagonize the activity of corticosterone. We hypothesized that the blocking of βAR and/or GR would produce selective inhibition of lung injury and/or inflammation and associated signaling events caused by exposure to ozone in rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats (10 weeks of age), purchased from Charles River Laboratory (Raleigh, NC) were housed in pairs in polycarbonate cages containing beta chip bedding under controlled conditions (21°C, 50–65% relative humidity and 12h light/dark cycle). Rats were provided with standard Purina (5001) rat chow (Brentwood, MO) and water ad libitum, and housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) approved animal facility. Animal procedures were approved by the US Environmental Protection Agency, National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Because we previously determined that 5–10% of male WKY rats develop spontaneous cardiac hypertrophy (Shannahan et al., 2010), all animals were evaluated for evidence of cardiac hypertrophy relative to body weights at necropsy. Those with 20% or greater increases in the heart to body weight ratio were removed from further data analysis.

Drug pretreatments and ozone exposures

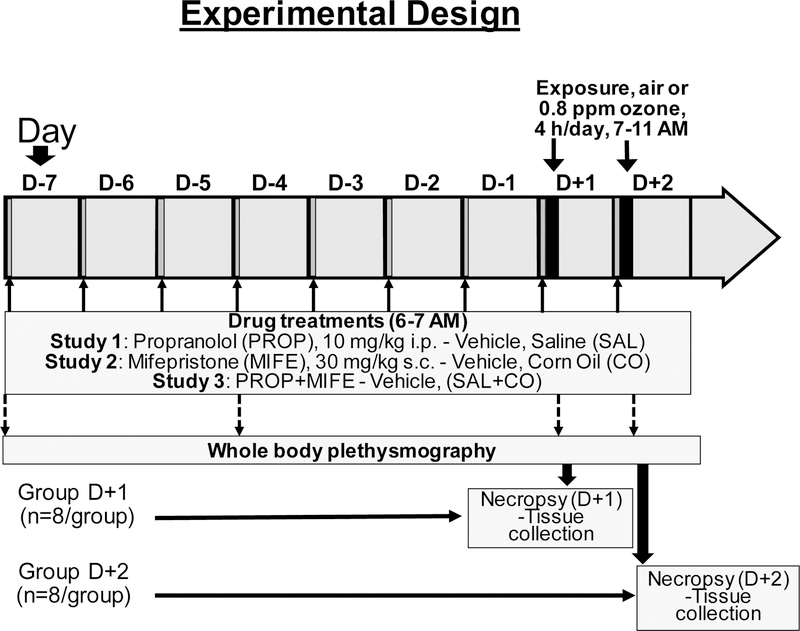

Three studies were conducted for each protocol involving PROP, MIFE, and PROP followed by MIFE (PROP+MIFE) pretreatments (Fig. 1). For each study, rats were randomized by body weight into four groups (vehicle/air, drug/air, vehicle/ozone, drug/ozone) and time point (one day, D+1; or two days, D+2) (n=8/group). In the first study, rats were injected i.p. with sterile saline (1 mL/kg) or propranolol hydrochloride (PROP, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO; 10 mg/kg in saline). In the second study, rats were injected s.c. with pharmaceutical grade corn oil (1 mL/kg) or mifepristone (MIFE, Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI; 30 mg/kg in corn oil). In the third study, control rats were injected with saline (1 mL/kg, i.p.) followed by corn oil (1 mL/kg, s.c.) while the drug-treated group was injected with PROP (10 mg/kg, i.p.) followed by MIFE (30 mg/kg, s.c.) (PROP+MIFE). For all three studies, the vehicle/drug pretreatments began seven days prior to the start of air or ozone exposure (from Day-7 to Day-1 in the morning) and continued each day of air or ozone exposure (D+1 and D+2) (Fig.1). The drug concentrations, the route of administration and the treatment durations were based on literature review of previously published papers examining the roles of AR and GR in mediation of cellular responses (Bible et al., 2015; Mohr et al., 2011; Sharrett-Field et al., 2013; Pitman et al., 2011). The dose levels we used for propranolol and mifepristone in rats were higher than what are used for humans. The maximum therapeutic dose for mifepristone in Cushing’s syndrome patients is 20 mg/kg/day (https://reference.medscape.com/drug/mifeprex-korlym-mifepristone-343130), and for propranolol is ~9 mg/kg/day (https://reference.medscape.com/drug/inderal-inderal-la-propranolol-342364). However, generally higher doses of these drugs are used in research papers involving rodent studies. Rats were exposed to either filtered air or ozone (0.8 ppm) for 4h during D+1 and/or D+2 in individual wire-mesh cages placed in exposure chambers. The D+1 and D+2 exposure protocol allowed us to determine immediate effects of ozone on each day while achieving maximum injury/inflammation response on second day. We have noted that changes in inflammatory gene expression and glucose intolerance is readily apparent immediately post 4-hour ozone exposure, however, the inflammatory changes following exposure peaks at ~12–20 hours when some of the acute effects of ozone might be reversible if exposure is not repeated (Kodavanti et al., 2015, Miller et al., 2015, Miller et al. 2016a). Using one- or two-day exposure protocol, we were able to assess acute gene expression and hormone changes in D+1 animals exposed to ozone for 1-day, while obtaining peak inflammation and injury at D+2.

Figure 1: Schema of the experimental design.

For all three studies, the timing for drug pretreatments and the information on air or ozone exposure, plethysmography and necropsies are indicated by corresponding arrows. Animals assigned to 1 day (4 hr) air or ozone exposure are referred as group D+1 and those assigned to 2 consecutive days of exposure are referred as group D+2. Animals assigned to group D+2 were subjected to plethysmography prior to the start of drug pretreatment, after 3 days of drug pretreatment (D-4) and immediately after each day of air/ozone exposure. Necropsy and tissue collection were performed immediately after exposure (D+1) or after exposure and plethysmography (D+2) (within 1–2 hours of exposure). Vehicles: SAL, saline; CO, corn oil; drugs: PROP, propranolol; MIFE, mifepristone.

Ozone was generated using a silent arc discharge generator (OREC, Phoenix, AZ) and delivered to 1000 L Hinners-type chambers using mass flow controllers. O3 concentration was recorded continuously by photometric analyzers (API Model 400, Teledyne, San Diego, CA). Chamber temperature (average °F) and relative humidity (RH: average %) were measured continuously and recorded hourly. The mean ozone chamber concentration was 0.803±0.002 ppm (Mean ± standard deviation). The RH for control chamber was 49±4 and ozone chamber was 46±3. The temperature of control chamber was 72.8±0.3 °F and ozone chamber was 74.2±0.4 °F. The control chamber flow was maintained at 256±24 while ozone chamber flow at 261±3 liters per minute).

Whole body plethysmography

In rats assigned to the D+2 group, ventilatory parameters were measured in unrestrained animals using whole body plethysmography (WBP) prior to drug treatments, during drug treatments and immediately after each day of air or ozone exposure. Briefly, rats were placed in pre-calibrated WBP chambers (Model PLY3213; Buxco Electronics, Inc., Wilmington, NC). During the first two minutes, the rats were allowed to acclimate. Then data were averaged for a total time of 5 minutes using EMKA iox 2 software (SCIREQ, Montreal, Canada). Ventilatory parameters included breathing frequency, tidal volume (TV), minute volume (MV), peak inspiratory flow (PIF), peak expiratory flow (PEF), inspiratory time (IT), expiratory time (ET), and enhanced pause (Penh), an index of air flow limitation (Hamelmann et al., 1997).

Necropsy and collection of samples

Immediately after exposure on day 1 (D+1), and after exposure and plethysmography on day 2 (D+2), rats were necropsied during the course of 1–2 hours. The rats were euthanized with an overdose of Fatal Plus (sodium pentobarbital, Virbac AH, Inc., Fort Worth, TX; >200 mg/kg, i.p.). Blood samples were collected from the abdominal aorta directly in vacutainer tubes. EDTA containing blood samples were used to perform complete blood count on a Beckman-Coulter AcT blood analyzer (Beckman-Coulter Inc., Fullerton, California). Additionally, blood smears were prepared and stained with Wright-Giemsa (Fisher Scientific) using a Hema-Tek 2000 slide stainer (Miles, Inc., Elkhart, IN, USA). Because this hematology analyzer provided data for only total white blood cells and lymphocytes, additional blood smear slides were used to verify the number of lymphocytes and to evaluate relative numbers of monocytes and neutrophils for the D+1 animals based on 100 white blood cells per slide.

The right lung was lavaged with Ca2+ and Mg2+ free PBS, pH 7.4, at 37 °C. The lavage volume was calculated based on 28 mL/kg body weight total lung capacity, and the right lung weight being 60% of total lung weight (Bass et al., 2013). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was used to determine total cell count (Z1 Coulter Counter, Coulter, Inc., Miami, FL) and cell differentials by preparing Cytospin slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). These slides were stained with Diff-Quik (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cell differentials were performed under light microscopy (300 cells/slide). Cell-free BALF (supernatant from whole BALF centrifuged at 1500xg) was used to measure total protein (Coomassie plus Protein Assay Kit, Pierce, Rockford, IL), albumin (DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN), and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) activity (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis IN) using commercially available kits adapted for use on a Konelab Arena 30 clinical analyzer (Thermo Chemical Lab Systems, Espoo, Finland). Following lavage, the right caudal lobe was removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for RNA extraction.

Lung RNA Isolation and real time-quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from a uniform portion (10–20 mg) of the right caudal lung lobe using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA was quantified using a Qubit 2.0 fluorimeter (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and reverse transcribed using Qscript cDNA Supermix (Quanta Biosciences, Beverly, MA). Primers were designed using sequences annotated in NCBI and obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc (Coralville, IA) including: β-Actin (Actb): f-CAACTGGGACGATATGGAGAAG, r-GTTGGCCTTAGGGTTCAGAG; tumor necrosis factor (tnf) f-ACCTTATCTACTCCCAGGTTCT, r-GGCTGACTTTCTCCTGGTATG; Interleukin 6 (Il6) f-CTTCACAAGTCGGAGGCTTAAT, r-GCATCATCGCTGTTCATACAATC; Chemokine (C-X-C motif) -ligand 2 (Cxcl2 or Mip2) f- GCCTCGCTGTCTGAGTTTATC, r- GAGCTGGCCAATGCATATCT; Metallothionein-2 (Mt2a) f- CAGCGATCTCTCGTTGATCTC, r- GGAGGTGCATTTGCATTGTT; TSC22 domain family protein 3 (Tsc22d3 or Gilz) f- CCGAATCATGAACACCGAAATG, r- GCAGAGAAGAGAAGAAGGAGATG. Quantitative PCR was performed for each gene using SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) on the Applied Biosystems 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Foster City, CA). Relative mRNA expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method following initial normalization to the housekeeping gene (Actb) and then with the respective vehicle-air control group. The determination of lung mRNA expression was performed only for D+1 samples since it has been shown that ozone-induced increases in mRNA expression precedes the release of associated proteins and inflammation (Hollingsworth et al., 2007; Kodavanti et al., 2015).

Cytokine quantification

Serum and BALF cytokine concentrations were quantified using the V-PLEX proinflammatory panel 2 (rat) kit per manufacturer’s protocol (Mesoscale Discovery Inc., Rockville, MD). The electrochemiluminescence signals for each protein were detected using Meso Scale Discovery® platform (Mesoscale Discovery Inc., Rockville, MD). In control animals in which the levels of some cytokines in BALF were below the assay detection limit, the values were substituted with the lowest quantified value for the given cytokine in the group. Measurement of BALF and plasma cytokines was restricted only to D+2 samples since it has been noted that ozone-induced inflammation is maximal at this time point (Ward et al., 2015).

Statistics

For all endpoints, data were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). PROP, MIFE and MIFE+PROP studies were treated as independent experiments. D+1 and D+2 exposure groups were also treated as independent experiments. The two independent variables were exposure (air or 0.8 ppm ozone) and pretreatment (vehicle or drug). The Holm-Sidak post-hoc test was used to correct for all multiple comparisons and significant differences were considered when a P-value of ≤ 0.05 was achieved. All data (n=6–8 animals/group) are expressed as mean ± SEM and GraphPad prism 6.07 software was used for statistical analysis. For pulmonary gene expression analysis only, outliers were identified based on the false discovery rate and discarded using the ROUT method (robust regression and outlier removal (Motulsky and Brown, 2006).

RESULTS

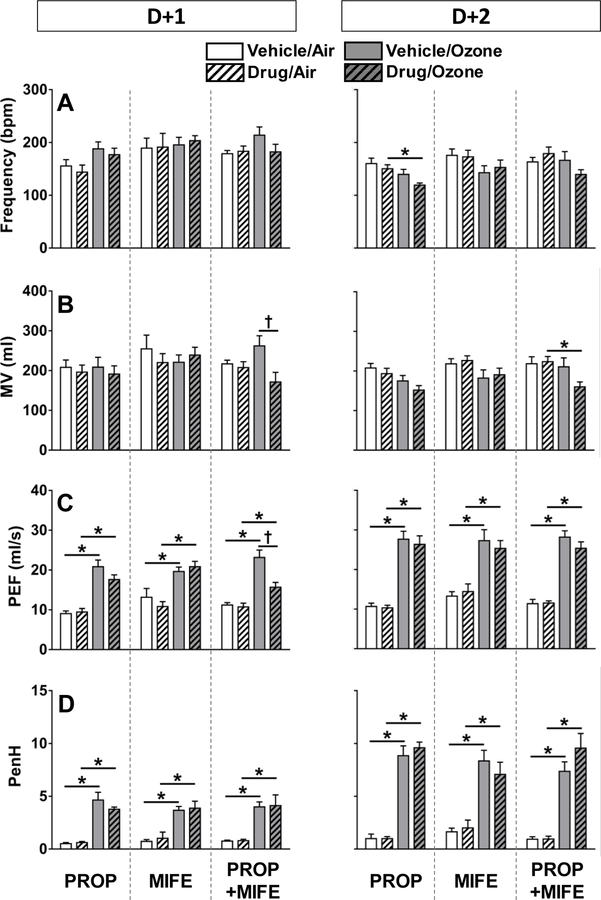

Ozone-induced changes in ventilatory parameters are not impacted by PROP, MIFE and PROP+MIFE pretreatment

Post-exposure WBP was performed to determine potential impact of drug-treatments and ozone on breathing parameters. In air-exposed rats, drug pretreatments did not affect any of the ventilatory parameters at D+1 or D+2 (Fig. 2). In ozone-exposed vehicle-treated rats, PEF and corresponding PenH values were consistently increased, both on D+1 and D+2, indicative of labored breathing. In ozone-exposed rats, PROP pretreatment was without effect on D+1, however, on D+2, this combination led to significantly reduced frequency of breathing (Fig. 2A). In ozone exposed MIFE-pretreated rats, results were similar to the ozone-only group. Finally, in the ozone-exposed PROP+MIFE pretreated rats, MV was significantly reduced at D+2 (Fig. 2B). Notably, immediately after the second day of exposure, PenH values were further increased in all ozone-exposed rats on D+2 (D+2>D+1), and no drug-related influences were apparent (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2: Ventilatory parameters in vehicle- or drug-pretreated rats after each day of air or ozone.

Ventilatory parameters determined after the first (D+1) and second (D+2) day of air or 0.8 ppm ozone exposure are shown (pre-air or -ozone exposure data are not shown). The breathing parameters indicate mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) of n=6–8 animals/group. Significant differences between groups (P ≤ 0.05) are indicated by * for ozone effect and by † for drug pretreatment effect. A) Breathing frequency, B) minute volume (MV), C) peak expiratory flow (PEF), D) enhanced pause (PenH).

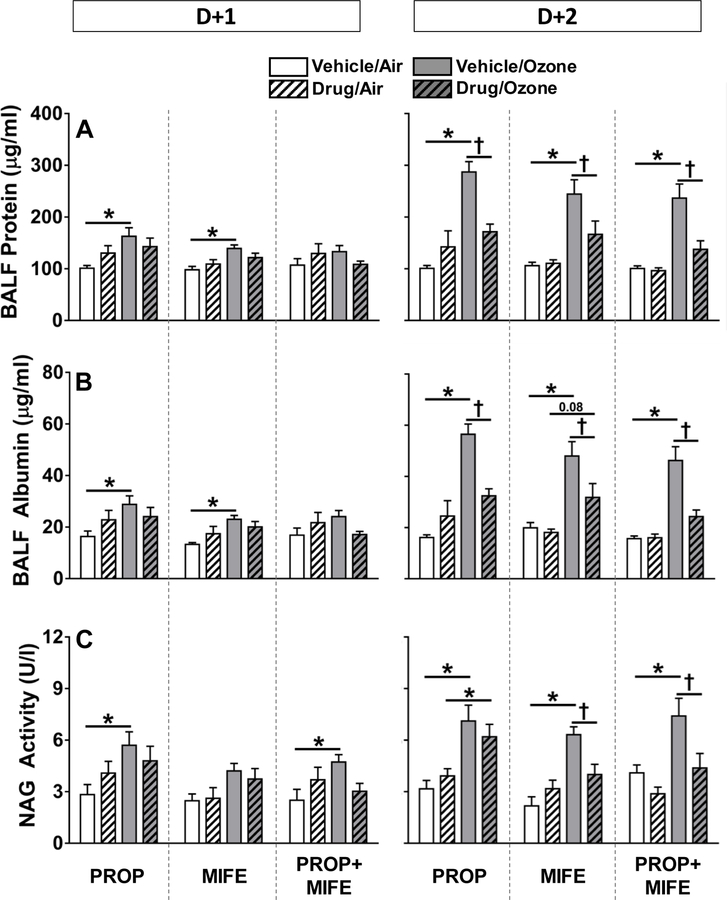

Ozone-induced pulmonary injury and inflammation are reduced by PROP, MIFE and/or PROP+MIFE pretreatments

Drug pretreatment in air-exposed rats did not influence any of the measures of lung injury and inflammation. Pulmonary vascular leakage, as measured by protein and albumin content in BALF, is a key event occurring after ozone exposure. Ozone-induced BALF protein (Fig. 3A) and albumin (Fig. 3B) tended to increase in all vehicle-pretreated rats at D+1. On D+2 all vehicle-pretreated ozone-exposed rats demonstrated marked increases in BALF protein and albumin that were diminished with all drug pretreatments. NAG activity in BALF, a marker of macrophage activation, was increased after both days of ozone exposure in vehicle-pretreated animals (D+2>D+1) (Fig. 3C). Ozone-induced increases in NAG activity on D+2 were attenuated by MIFE and MIFE+PROP but not PROP (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3: The influence of drug pretreatments on ozone-induced BALF protein leakage and N-acetyl glucosaminidase (NAG) activity.

Protein (A), albumin (B), and NAG activity (C) were determined in BALF collected immediately following exposure to air or 0.8 ppm ozone, 4 hr/day for 1 day (D+1) or 2 days (D+2). Values indicate mean ± SE of n=6–8 animals/group. Significant differences between groups (P ≤ 0.05) are indicated by * for ozone effect in matching pretreatment groups, and by † for drug effect in matching exposure groups.

To determine the extent of ozone-induced inflammation in the lungs and effects of drug pretreatments, BALF total cells, neutrophils and lymphocytes were counted. Total cells in BALF were not changed by any of the drug pretreatments or ozone exposure except for a non-significant reduction in all ozone exposed rats in the PROP study at D+1 (Fig. 4A). Ozone exposure on D+1 did not increase BALF neutrophil influx substantially in any of the vehicle or drug-pretreated groups except for a small but significant increase in saline-pretreated rats in the PROP study. The ozone-induced lung neutrophilia was significant in all vehicle-pretreated rats on D+2. This ozone-induced neutrophilia was prevented by PROP and PROP+MIFE but not MIFE alone (Fig. 4B). Ozone exposure resulted in reduced number of lymphocytes in BALF on D+1 and D+2 in all vehicle-treated rats. There was no effect of any drug pretreatment on ozone-induced reduction in BALF lymphocytes (Fig. 4 C).

Figure 4: The influence of drug pretreatments on ozone-induced changes in lung inflammation as determined by BALF cell count.

Total cells (A), neutrophils (B) and lymphocytes (C) were determined in BALF collected immediately following exposure to air or ozone (0.8 ppm), 4 hr/day for 1 day (D+1) or 2 consecutive days (D+2). Values indicate mean ± SE of n=6–8 animals/group. Significant differences between groups (P ≤ 0.05) are indicated by * for ozone effect in matching pretreatment groups, and by † for drug effect in matching exposure groups.

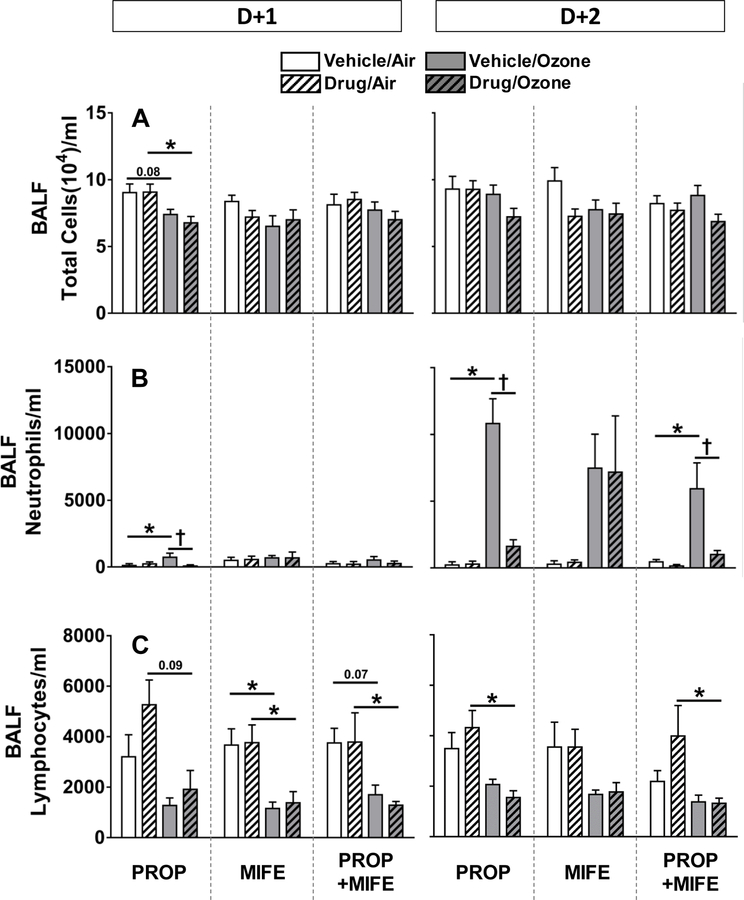

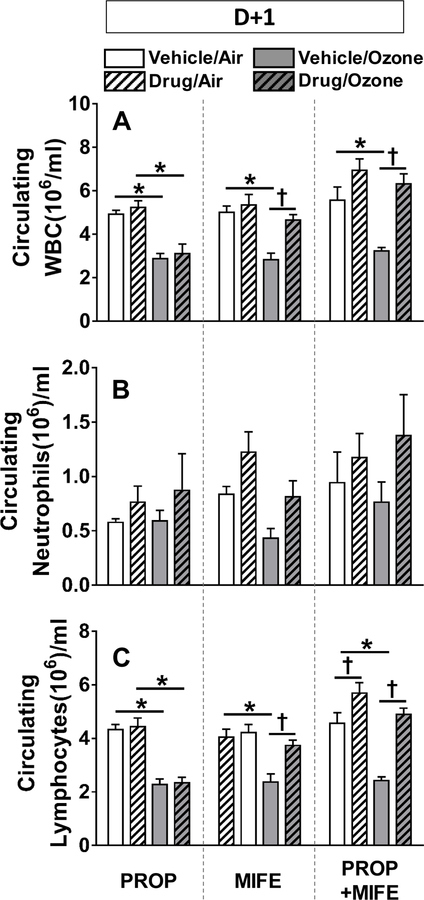

Ozone-induced decreases in circulating white blood cells (WBC) and lymphocytes were reversed by MIFE pretreatment

To determine the relationship between levels of immune cells in the lung and in the circulation, complete blood count and cell differentials were performed. Circulating total WBC were reduced to nearly half in all vehicle pretreated rats exposed to ozone (Fig. 5A). This ozone-induced decrease was prevented in rats pretreated with MIFE or PROP+MIFE but not PROP alone. This pattern was not replicated in circulating neutrophils as no specific exposure- or pretreatment-related changes were noted in the D+1 group (Fig. 5B). Since nearly 70–90% of circulating WBC (Cameron and Watson, 1949) in this strain of rats are lymphocytes, the changes in circulating lymphocytes reflected the changes observed in WBC after ozone exposure and drug-pretreatments (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5: The effects of drug pretreatments on ozone-induced changes in circulating white blood cells (WBC) in rats.

Circulating total white blood cells (A), neutrophils (B) and lymphocytes (C) were determined in rats immediately after exposure to air or 0.8 ppm ozone, 4 hr/day for 1 day (D+1). Values indicate mean ± SE of n=6–8 animals/group. Significant differences between groups (P ≤ 0.05) are indicated by * for ozone effect in matching pretreatment groups, and by † for drug effect in matching exposure groups.

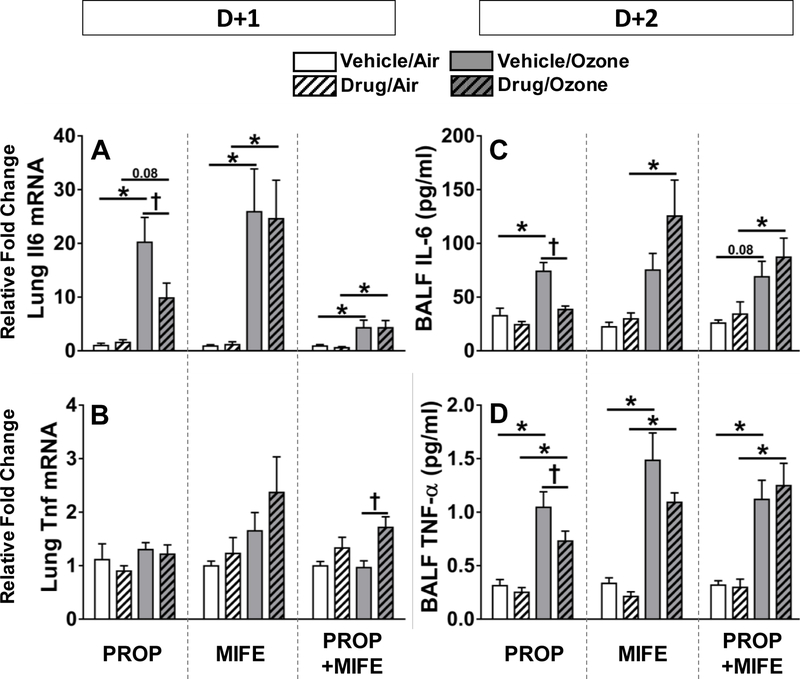

Ozone-induced increases in expression of pro-inflammatory mediators in the lung are diminished by PROP pretreatment

Lung mRNA (D+1) and BALF protein levels (D+2) of IL-6 and TNF-α were assessed to determine if the influence of PROP and MIFE on ozone-induced inflammatory changes occur at the transcriptional and signaling levels. Ozone exposure was associated with increases in Il6 lung mRNA and BALF protein in all vehicle pretreated rats. Ozone’s effect on Il6 mRNA and BALF protein was significantly reduced in animals pretreated with PROP but not MIFE or PROP+MIFE (Fig. 6A, 6C). Although no consistent ozone exposure or drug pretreatment-related changes were apparent on Tnfα mRNA expression as determined on D+1, marked increases in BALF TNF-α protein were noted in all ozone-exposed vehicle-pretreated rats at D+2 (Fig. 6B, 6D). This ozone effect on TNF -α was slightly reduced in rats pretreated with PROP, however, there was no significant effect of MIFE or PROP+MIFE (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6: Ozone-induced changes in Tnfα and Il6 lung mRNA and BALF proteins in rats pretreated with βAR and GR antagonists.

Lung mRNA expression of Il6 (A) and Tnfα (B) were determined in D+1 groups while BALF protein levels of IL-6 (C) and TNF-α (D) were assessed in D+2 groups. Values indicate mean ± SE of n=6–8 animals/group. Significant differences between groups (P ≤ 0.05) are indicated by * for ozone effect in matching pretreatment groups, and by † for drug effect in matching exposure groups.

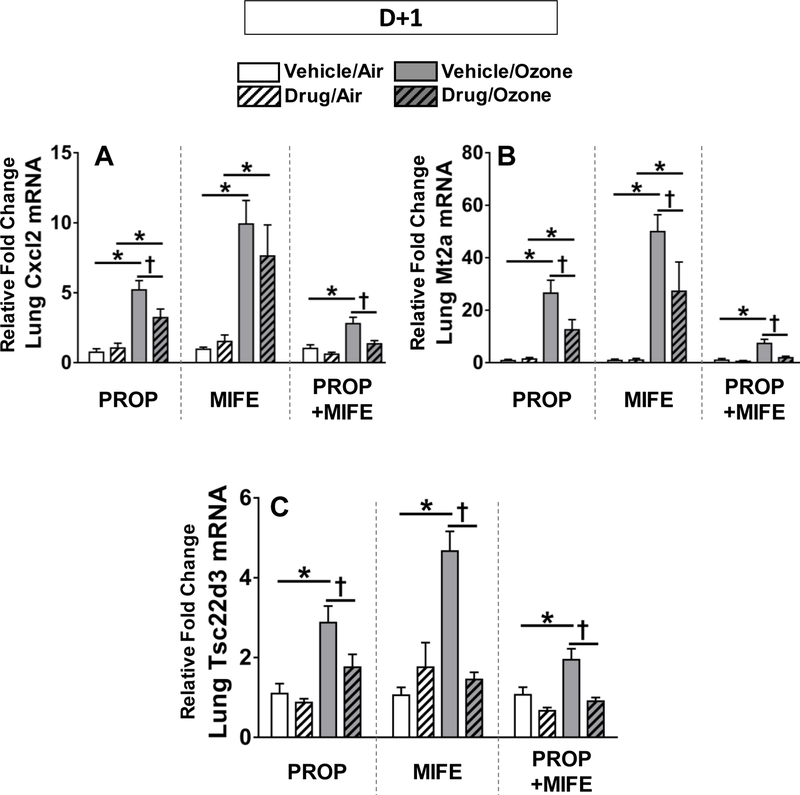

In addition to the above mentioned inflammatory cytokines, we also determined the effect of PROP and MIFE pretreatments at the D+1 time point on two lung transcripts known to be upregulated after ozone exposure: Cxcl2 (also known as Mip2, a neutrophil chemoattractant) and Mt2a (metallothionein 2a, an acute phase reactant (Henriquez et al., 2017; Ward et al., 2015). Ozone exposure increased expression of Cxcl2 and Mt2a in vehicle pretreated rats (Fig. 7A, 7B). The ozone-induced up-regulation of Cxcl2 was significantly decreased only by PROP and PROP+MIFE pretreatments whereas MIFE alone did not have any effect (Fig. 7A). Ozone-induced upregulation of Mt2a, a free radical scavenger released in inflammatory conditions (Inoue et al., 2008), was significantly reduced by all drug pretreatments (Fig. 7B). The expression of the glucocorticoid responsive gene Tsc22d3 was also markedly increased after ozone exposure in all vehicle-pretreated rats. That ozone-induced increase was diminished by PROP, MIFE and PROP+MIFE (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7: The effect of drug pretreatments on ozone-induced increases in pulmonary Cxcl2, Mt2a and Tsc22d3 mRNA expression.

Relative lung mRNA expression was determined in D+1 groups for Cxcl2 (also known as Mip2; A), Mt2a (B) and Tsc22d3 (C). Values indicate mean ± SE of n=6–8 animals/group. Significant differences between groups (P ≤ 0.05) are indicated by * for ozone effect in matching pretreatment groups, and by † for drug effect in matching exposure groups.

DISCUSSION

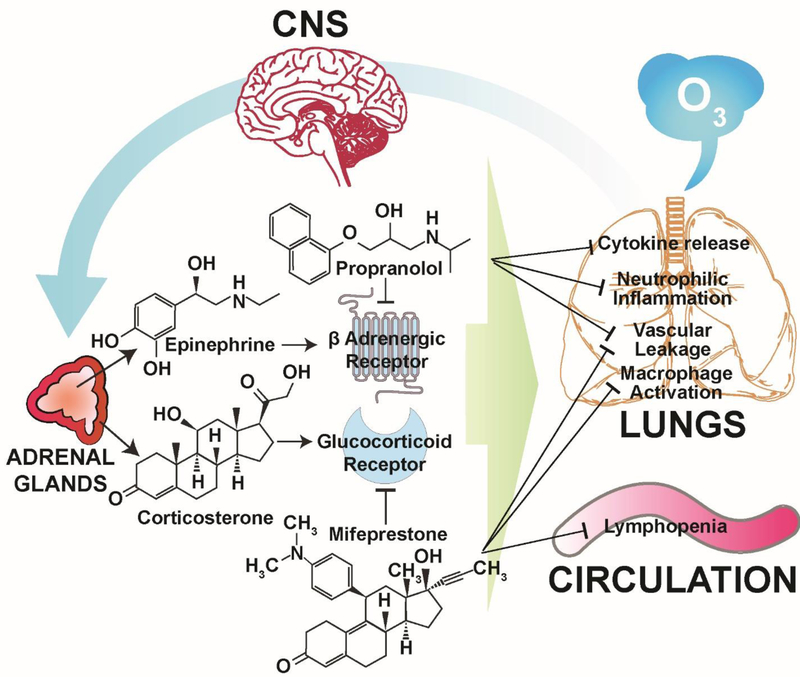

In this study, we blocked the activity of stress hormone receptors βAR and GR, individually or together, to better understand and define the role of stress hormones in ozone-induced pulmonary effects. The experimental design was developed to separately account for the effects likely to be mediated via epinephrine, corticosterone, or both, by pretreating rats with PROP, MIFE or PROP+MIFE, respectively (Fig. 8). We hypothesized that βAR and GR blockade would prevent ozone-mediated activation of these receptors by stress hormones, and also downstream signaling events in the lung, leading to reduction in ozone-induced pulmonary effects. Since only PROP+MIFE but not other individual pretreatments reduced minute volume and PEF in ozone-exposed rats, the degree of ozone-induced lung edema or neutrophilic inflammation in the PROP and/or MIFE-pretreated rats were likely not influenced by the possibility of reduction in lung ozone dose. Nevertheless, PROP, MIFE or PROP+MIFE (inhibition of βAR and/or GR) were sufficient to attenuate ozone-induced pulmonary protein leakage; however, only PROP and PROP+MIFE (inhibition of βAR or βAR+GR) reduced ozone-induced lung neutrophilic inflammation, and pro-inflammatory cytokine increases. On the other hand, only MIFE (inhibition of GR) pretreatment reversed ozone-induced lymphopenia and increases in BALF NAG activity which reflects macrophage activation (Fig.8). These data suggest that βAR and GR have distinct roles in mediating inflammatory cell-specific responses induced by ozone. It is noteworthy that the pretreatment of animals with PROP, MIFE or PROP+MIFE themselves, had very little if any pulmonary and systemic effect in air-exposed animals, highlighting the role of βAR and GR as specific modulators of ozone–induced pulmonary vascular leakage and innate immune responses. Since βAR and GR have been widely manipulated in cardiopulmonary diseases, those receiving βAR and GR-related treatments might have altered susceptibility to high levels of ozone or other pulmonary irritants.

Figure 8: Proposed mechanism by which βAR and GR antagonists reduce ozone-induced pulmonary protein leakage, cytokine expression, neutrophilic inflammation and lymphopenia.

This schematic is based on our earlier studies that ozone-induced lung injury and inflammation are mediated through neuroendocrine activation of stress response and involves the release of adrenal-derived stress hormones, epinephrine and corticosterone (Kodavanti, 2016). Ozone-induced effects are inhibited by pretreatment of rats with PROP and/or MIFE.

Ambient levels of 0.2 ppm ozone were recorded during a recent 2017 weather event in Texas, United States (EPA, 2017). This concentration or even higher levels have been used in several human clinical studies during intermittent exercise (Miller et al., 2016c). Although ozone concentration of 0.8 ppm used in this study is high relative to those used in human clinical studies, it has been shown that 0.2 ppm ozone exposure during intermittent exercise can result in a dose that is 4–5 times higher than the dose encountered by resting rodent during inactivity period (Hatch et al., 2013).

We selected PROP and MIFE to evaluate the role of βAR and GR activation in ozone-induced pulmonary injury/inflammation since these drugs have been validated for their receptor specificity (Alamo et al., 2017; Kubo et al., 2004). PROP, a non-selective βAR antagonist, blocks activity of both β1 and β2 AR. Although epinephrine is a potent agonist of virtually all AR (Molinoff et al., 1984), in this study we focused only on the role of βAR activity since these receptors are enriched in cardiopulmonary tissues and have a major role in autonomic regulation and innate immune homeostatic balance (Bible et al., 2015; Folwarczna et al., 2011; Hegstrand and Eichelman, 1983; Kolmus et al., 2015; Sato et al., 2010). MIFE, a GR antagonist, has been widely used to antagonize the GR in psychiatric disorders (Howland, 2013) and adrenal hyper-production of cortisol (Morgan and Laufgraben, 2013). Several experimental studies have validated its anti-GR activity in animal models (Navarro-Zaragoza, et al., 2017; Sharrett-Field, et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). Although these pharmacological agents have shown efficacy for both sexes, we focused on male WKY rats for this ozone study since the males of spontaneously hypertensive rats, which are derived from WKY, are more susceptible than females to pulmonary inflammation induced by another inhaled pollutant - tobacco smoke (Shen et al., 2017).

Due to the fact that the tissue dose of ozone might influence the degree of vascular permeability and inflammation, we assessed breathing parameters to estimate the potential impact of ozone dose (Dye et al., 2015; Snow et al., 2016). It is noteworthy that no drug pretreatments affected ventilatory parameters in air-exposed rats. As we have observed in previous studies (Dye et al., 2015), all ozone-exposed rats regardless of drug pretreatment demonstrated increases in PenH and PEF, measures of labored breathing, but had no effect on minute volume, except for a small decrease only in PROP+MIFE rats. Since the manipulation of both AR and GR has been shown to change breathing parameters in humans (Antonelli-Incalzi and Pedone, 2007; Hirst and Lee, 1998), the observed small changes in MV only in PROP+MIFE group may be due to the combined βAR+GR blockade. Since only this group, but not PROP or MIFE alone, showed any reduction in minute volume after ozone exposure, it is not likely that the lung injury and inflammation changes are impacted by the differential ozone dose with different pretreatments.

There are a number of potential mechanisms by which lung vascular permeability might be increased by ozone. An imbalance between peripheral sympathetic influence due to increased epinephrine and acute parasympathetic dominance on the heart can shift the blood flow from high resistant peripheral vasculature to low resistant pulmonary vasculature, leading to pulmonary microvascular leakage (Li and Pauluhn, 2017). Our previous work has shown that ozone increases circulating epinephrine with no change in norepinephrine (Miller et al., 2015, 2016b). Thus, lung permeability changes are likely influenced by epinephrine’s effect on β2AR, which caused dilation of pulmonary vasculature, an effect that could be prevented by PROP antagonism of these receptors (Pourageaud et al., 2005). Since PROP and MIFE, each prevented ozone-induced lung microvascular leakage, it is possible that AR and GR effects are inter-related and/or centrally-mediated. Both drugs are known to cross the blood brain barrier and regulate expression of stress responses through their effects on the hypothalamus (Check et al., 2014; Neil-Dwyer et al., 1981). Interestingly, GR activation can also mediate effects of norepinephrine to regulate blood pressure (Shi et al., 2016).

Ozone-induced innate inflammatory responses in the lung involve neutrophil extravasation through enhanced trans-endothelial migration (Krishna et al., 1997). Catecholamines and glucocorticoids, which are increased by ozone inhalation (Bass et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2015, 2016a, 2016b) play a central role in initiating a dynamic process of egress of innate immune cells from their site of depot to the circulation and then migration to the site of inflammation, in this case the lung. It has been shown that increased circulating epinephrine and corticosterone can induce the innate neutrophil immune response (Dhabhar et al., 2012). We have shown that increases in pulmonary neutrophil extravasation is associated with ozone-induced increases in stress hormones and that adrenal demedullation and/or total adrenalectomy diminishes this inflammatory effect of ozone (Miller et al., 2016b). Here we observed that inhibiting βAR with PROP and both βAR+GR with PROP+MIFE, mimicking systemic impacts of adrenal demedullation and total adrenalectomy, respectively, nearly inhibited ozone-induced neutrophil increases in the lung in its entirety. However, inhibition of only GR using MIFE was ineffective in reversing lung neutrophilic inflammation, suggesting that βAR activation might be central in neutrophil extravasation to the lung after ozone exposure. This is further supported by studies demonstrating that PROP pretreatment prevents cigarette smoke-induced lung damage (Zhou et al., 2014a), and improves survival in a sepsis model (Wilson et al., 2013).

The effects of AR and GR manipulation on ozone-induced responses are immune cell specific. The lack of ozone-induced lymphopenia in MIFE- but not PROP-pretreated rats highlights the role of GR in modulating the migration, redistribution and proliferation of lymphoid cells in the circulation (Dhabhar et al., 2012). This effect of MIFE was not recapitulated in the number of BALF lymphocytes, suggesting that ozone-induced changes in circulating lymphocytes are likely influenced by GR-mediated egress from their storage site but not extravasation into the lung. The acute stress response fine-tunes immune function depending on the timing and magnitude of the stressor by enhancing innate and adaptive immune responses (Dhabhar, 2014). MIFE pretreatment has been shown to reestablish lymphocyte mediated immune responses in immunosuppressed mice (Rearte et al., 2010). Further, a MIFE-mediated reduction in glucocorticoid-induced lymphocyte apoptosis may also explain these results (Smith and Cidlowski, 2010) since glucocorticoids inhibit the release of lymphocytes into the circulation and induce apoptosis (Baschant and Tuckermann, 2010; Laakko and Fraker, 2002; Viegas et al., 2008).

A marked inhibition of ozone-induced increase in BALF NAG activity by MIFE might indicate a role for GR in modulating the macrophage response. It is possible that the initiation of a stress response by epinephrine might modulate the lung innate immune response and subsequent systemic corticosterone immune effects (Johnson et al., 2005; Vida et al. 2011; Zhou et al., 2014b). This assumption is supported by the observation that PROP markedly diminished ozone-induced inflammatory cytokine increases and neutrophilic inflammation in the lung, supporting a major contribution of βAR in local pulmonary modulation of the immune responses. Although the activation of the sympathetic arm of the stress axis (epinephrine and norepinephrine) has been shown to inhibit innate immune responses in humans (Kox et al., 2014), it is known that β2AR, which are abundant in the lung, can modulate nuclear factor kappa-beta-mediated inflammatory processes. Previous studies have shown that PROP blocked the stress-induced elevation of circulating IL-6 levels (van Gool et al., 1990) and reduced air pollution-induced increases in IL-6 in mice (Chiarella et al., 2014). Since in vivo pulmonary effects of ozone can be blocked by inhibiting βAR and GR receptors, and ozone can increase circulating epinephrine and corticosterone through the activation of SAM and HPA axes, it is likely that when encountered by the lung, ozone acts upstream to increase βAR and GR activity systemically, and can also have direct lung cellular effects downstream of βAR and GR receptor activation to interrupt cell signaling.

Mt2a, known to be upregulated by ozone (Inoue et al., 2008), was also increased in vehicle-pretreated rats exposed to ozone, however, this effect was markedly reduced by both PROP and MIFE, suggesting that the neuroendocrine response is linked to ozone-induced acute phase protein expression. In humans, Mt2a gene transcription is activated by GR activation (Sato et al., 2013) and in a murine restrained stress model, Mt2a expression correlated with increased corticosterone levels (Jacob et al., 1999). This observation is in agreement with previous work from our lab showing that the removal of adrenal glands – which is the source of both epinephrine and corticosterone – reduced the ozone-induced up-regulation of Mt2a and many other acute phase response genes (Henriquez et al., 2017). The increased expression of the glucocorticoid-responsive gene Tsc22d3 after ozone exposure supports the corticosterone-mediated activation of GR in the lungs.

In conclusion, by blocking βAR and GR activity using PROP and MIFE pretreatments, respectively, we selectively minimized ozone-induced lung protein leakage, macrophage activation, neutrophilic inflammation, lymphopenia, and pulmonary inflammatory cytokine expression in rats (Fig. 8). These findings suggest a significant mechanistic role of ozone-induced increases in circulating stress hormones, the activation of βAR and GR, and the possible downstream effects on cell signaling through these receptors that result in lung injury and inflammation. Moreover, since βAR and GR agonists are commonly used in the treatment of chronic inflammatory conditions of the lung, including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, those receiving such treatments may show differential susceptibility to air pollution-induced lung effects.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Drs. Aimen Farraj, Stephen Gavett, Wayne Cascio and Ian Gilmour of the US EPA for their critical review of the manuscript, and Ms. Cynthia Fisher for her help in the mRNA PCR experiment. We acknowledge the help of Dr. Mark Higuchi for performing inhalation exposures and Mr. Abdul Malek Khan in finalizing ozone exposure parameters. This work was supported in part by Fulbright (Becas Chile, CONICYT; IIE-15120279) to A.H. and the EPA-UNC Center for Environmental Medicine, Asthma and Lung Biology Cooperative Agreement (CR-83515201) as well as EPA-UNC Cooperative Training Agreement (CR-83578501).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The research described in this article has been reviewed by the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Agency, nor does the mention of trade names of commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

REFERENCES

- Alamo IG, Kannan KB, Bible LE, Loftus TJ, Ramos H, Efron PA, Mohr AM. 2017. Daily propranolol administration reduces persistent injury-associated anemia after severe trauma and chronic stress. J. Trauma Acute Care. Surg. 82(4), 714–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli-Incalzi R, Pedone C. 2007. Respiratory effects of beta-adrenergic receptor blockers. Curr. Med. Chem. 14(10), 1121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arjomandi M, Wong H, Donde A, Frelinger J, Dalton S, Ching W, Power K, Balmes JR. 2015. Exposure to medium and high ambient levels of ozone causes adverse systemic inflammatory and cardiac autonomic effects. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 308(12), H1499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A, Hernandez ML. The effect of environmental oxidative stress on airway inflammation. 2012. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 12, 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baschant U, Tuckermann J. 2010. The role of the glucocorticoid receptor in inflammation and immunity. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 120(2–3), 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass V, Gordon CJ, Jarema KA, MacPhail RC, Cascio WE, Phillips PM, Ledbetter AD, Schladweiler MC, Andrews D, Miller D, et al. 2013. Ozone induces glucose intolerance and systemic metabolic effects in young and aged Brown Norway rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 273, 551–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bible LE, Pasupuleti LV, Gore AV, Sifri ZC, Kannan KB, Mohr AM. 2015. Daily propranolol prevents prolonged mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in a rat model of lung contusion, hemorrhagic shock, and chronic stress. Surgery. 158(3), 595–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg PA. 2016. Mechanisms of the acute effects of inhaled ozone in humans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1860 12, 2771–2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DG, Watson GM. 1949. The blood counts of the adult albino rat. Blood. 4, 816–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzola M, Page CP, Rogliani P, Matera MG. 2013. β2-agonist therapy in lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 187(7), 690–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Check JH, Wilson C, Cohen R, Sarumi M. 2014. Evidence that Mifepristone, a progesterone receptor antagonist, can cross the blood brain barrier and provide palliative benefits for glioblastoma multiforme grade IV. Anticancer Res. 34(5), 2385–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarella SE, Soberanesm S, Urich D, Morales-Nebreda L, Nigdelioglu R, Green D, Young JB, Gonzalez A, Rosario C, et al. 2014β₂-Adrenergic agonists augment air pollution-induced IL-6 release and thrombosis. J. Clin. Invest. 124(7), 2935–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Topete D, Cidlowski JA. 2015. One hormone, two actions: anti- and pro-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Neuroimmunomodulation. 22(1–2), 20–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar FS, Malarkey WB, Neri E, McEwen BS. 2012. Stress-induced redistribution of immune cells--from barracks to boulevards to battlefields: a tale of three hormones--Curt Richter Award winner. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 37(9), 1345–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar FS. 2014. Effects of stress on immune function: the good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunol. Res. 58: 193–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duque EA, Munhoz CD. 2016. The Pro-inflammatory Effects of Glucocorticoids in the Brain. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 7, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye JA, Ledbetter AD, Schladweiler MC, Costa DL, Kodavanti UP. 2015. Whole body plethysmography reveals differential ventilatory responses to ozone in rat models of cardiovascular disease. Inhal. Toxicol. 27 Suppl 1, 14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA, 2007 Airnow.gov (2017. September 7). Retrieved from https://airnow.gov/index.cfm?action=airnow.mapsarchivedetail&domainid=29&mapdate=20170831&tab=2.

- Folwarczna J, Pytlik M, Sliwiński L, Cegieła U, Nowińska B, Rajda M. 2011. Effects of propranolol on the development of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in male rats. Pharmacol. Rep. 63(4), 1040–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gackière F, Saliba L, Baude A, Bosler O, Strube C. 2011. Ozone inhalation activates stress-responsive regions of the CNS. J. Neurochem. 117, 961–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CJ, Johnstone AF, Aydin C, Phillips PM, MacPhail RC, Kodavanti UP, Ledbetter AD, Jarema KA. 2014. Episodic ozone exposure in adult and senescent Brown Norway rats: acute and delayed effect on heart rate, core temperature and motor activity. Inhal. Toxicol. 26, 380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch GE, McKee J, Brown J, McDonnell W, Seal E, Soukup J, Slade R, Crissman K, Devlin R. 2013. Biomarkers of Dose and Effect of Inhaled Ozone in Resting versus Exercising Human Subjects: Comparison with Resting Rats. Biomark Insights. 8, 53–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelmann E, Schwarze J, Takeda K, Oshiba A, Larsen GL, Irvin CG, Gelfand EW. 1997Noninvasive measurement of airway responsiveness in allergic mice using barometric plethysmography. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156(3), 766–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegstrand LR, Eichelman B. 1983. Increased shock-induced fighting with supersensitive β-adrenergic receptors. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 19(2), 313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriquez A, House J, Miller DB, Snow SJ, Fisher A, Hongzu R, Schladweiler MC, Ledbetter AD, Wright F, Kodavanti UP. 2017. Adrenal-derived stress hormones modulate ozone-induced lung injury and inflammation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 329, 249–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst SJ, Lee TH. 1998. Airway smooth muscle as a target of glucocorticoid action in the treatment of asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 158(5 Pt 3), S201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth JW, Kleeberger SR, Foster WM. 2007. Ozone and pulmonary innate immunity. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 4(3), 240–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland RH. 2013. Mifepristone as a therapeutic agent in psychiatry. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health. Serv. 51(6), 11–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Takano H, Kaewamatawong T, Shimada A, Suzuki J, Yanagisawa R, Tasaka S, Ishizaka A, Satoh M. 2008. Role of metallothionein in lung inflammation induced by ozone exposure in mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45(12), 1714–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob ST, Ghoshal K, Sheridan JF. 1999. Induction of metallothionein by stress and its molecular mechanisms. Gene Expr. 7(4–6), 301–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, Campisi J, Sharkey CM, Kennedy SL, Nickerson M, Greenwood BN, Fleshner M. 2005. Catecholamines mediate stress-induced increases in peripheral and central inflammatory cytokines. Neuroscience. 135(4), 1295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakade AS, Kulkarni YS. 2014. Mifepristone: current knowledge and emerging prospects. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 112(1), 36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodavanti UP, Ledbetter AD, Thomas RF, Richards JE, Ward WO, Schladweiler MC, Costa DL. 2015. Variability in ozone-induced pulmonary injury and inflammation in healthy and cardiovascular-compromised rat models. Inhal. Toxicol. 27 Suppl. 1, 39–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodavanti UP. 2016. Stretching the stress boundary: Linking air pollution health effects to a neurohormonal stress response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1860 12, 2880–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmus K, Tavernier J, Gerlo S. 2015. β2-Adrenergic receptors in immunity and inflammation: stressing NF-κB. Brain Behav. Immun. 45, 297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kox M, van Eijk LT, Zwaag J, van den Wildenberg J, Sweep FC, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P. 2014. Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111(20), 7379–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna MT, Blomberg A, Biscione GL, Kelly F, Sandstrom T, Frew A, Holgate S. 1997. Short-term ozone exposure upregulates P-selectin in normal human airways. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 155(5), 1798–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo K, Kita T, Tsujimura T, Nakashima T. 2004. Effect of nicotine-induced corticosterone elevation on nitric oxide production in the passive skin arthus reaction in rats. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 94(1), 31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz T, Yamada KA, DaTorre SD, Corr PB. 1991. Alpha 1-adrenergic system and arrhythmias in ischaemic heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 12 Suppl. F, 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakko T, Fraker P. 2002. Rapid changes in the lymphopoietic and granulopoietic compartments of the marrow caused by stress levels of corticosterone. Immunology. 105(1), 111–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Pauluhn J. 2017. Phosgene-induced acute lung injury (ALI): differences from chlorine-induced ALI and attempts to translate toxicology to clinical medicine. Clin. Transl. Med. 6(1), 19, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB, Karoly ED, Jones JC, Ward WO, Vallanat BD, Andrews DL, Schladweiler MC, Snow SJ, Bass VL, Richards JE, et al. 2015. Inhaled ozone (O3)-induces changes in serum metabolomic and liver transcriptomic profiles in rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 286, 65–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB, Snow SJ, Henriquez A, Schladweiler MC, Ledbetter AD, Richards JE, Andrews DL, Kodavanti UP. 2016a. Systemic metabolic derangement, pulmonary effects, and insulin insufficiency following subchronic ozone exposure in rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 306, 47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB, Snow SJ, Schladweiler MC, Richards JE, Ghio AJ, Ledbetter AD, Kodavanti UP. 2016b. Acute ozone-induced pulmonary and systemic metabolic effects are diminished in adrenalectomized rats. Toxicol. Sci. 150 (2), 312–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB, Ghio AJ, Karoly ED, Bell LN, Snow SJ, Madden MC, Soukup J, Cascio WE, Gilmour MI, Kodavanti UP. 2016c. Ozone exposure increases circulating stress hormones and lipid metabolites in humans. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 193 (12), 1382–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr AM, ElHassan IO, Hannoush EJ, Sifri ZC, Offin MD, Alzate WD, Rameshwar P, Livingston DH. 2011. Does beta blockade post injury prevent bone marrow suppression? J Trauma. 70(5),1043–9, discussion 1049–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinoff PB. 1984. Alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes properties, distribution and regulation. Drugs. 28 Suppl. 2, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan FH, Laufgraben MJ. 2013. Mifepristone for management of Cushing’s syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 33(3), 319–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky HJ, Brown RE. 2006. Detecting outliers when fitting data with nonlinear regression – a new method based on robust nonlinear regression and the false discovery rate. BMC. Bioinformatics. 7,123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Zaragoza J, Laorden ML, Milanés MV. 2017. Glucocorticoid receptor but not mineralocorticoid receptor mediates the activation of ERK pathway and CREB during morphine withdrawal. Addict. Biol. 22(2), 342–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil-Dwyer G, Bartlett J, McAinsh J, Cruickshank JM. 1981. Beta-adrenoceptor blockers and the blood-brian barrier. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 11(6), 549–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley RH, Cidlowski JA. 2013. The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 132(5), 1033–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen J, Hougård K, Hertz M. 1978. Isoproterenol and propranolol: ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and effects on cerebral circulation in man. Stroke. 9(4), 344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petta I, Dejager L, Ballegeer M, Lievens S, Tavernier J, De Bosscher K, Libert C. 2016. The Interactome of the Glucocorticoid Receptor and Its Influence on the Actions of Glucocorticoids in Combatting Inflammatory and Infectious Diseases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80(2), 495–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman RK, Milad MR, Igoe SA, Vangel MG, Orr SP, Tsareva A, Gamache K, Nader K. 2011. Systemic mifepristone blocks reconsolidation of cue-conditioned fear; propranolol prevents this effect. Behav Neurosci. 125(4), 632–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourageaud F, Leblais V, Bellance N, Marthan R, Muller B. 2005. Role of beta2-adrenoceptors (beta-AR), but not beta1-, beta3-AR and endothelial nitric oxide, in beta-AR-mediated relaxation of rat intrapulmonary artery. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol. 372(1), 14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rearte B, Maglioco A, Balboa L, Bruzzo J, Landoni VI, Laborde EA, Chiarella P, Ruggiero RA, Fernández GC, Isturiz MA. 2010. Mifepristone (RU486) restores humoral and T cell-mediated immune response in endotoxin immunosuppressed mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 162(3), 568–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Shirakawa H, Tomita S, Tohkin M, Gonzalez FJ, Komai M. 2013. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor and glucocorticoid receptor interact to activate human metallothionein 2A. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 273(1), 90–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Arai M, Goto S, Togari A. 2010. Effects of propranolol on bone metabolism in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 334(1), 99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannahan JH, Schladweiler MC, Richards JH, Ledbetter AD, Ghio AJ, Kodavanti UP. 2010. Pulmonary oxidative stress, inflammation, and dysregulated iron homeostasis in rat models of cardiovascular disease. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. A. 73(10), 641–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrett-Field L, Butler TR, Berry JN, Reynolds AR, Prendergast MA. 2013. Mifepristone Pretreatment Reduces Ethanol Withdrawal Severity In Vivo. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 37(8), 1417–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen YH, Pham AK, Davis B, Smiley-Jewell S, Wang L, Kodavanti UP, Takeuchi M, Tancredi DJ, Pinkerton KE. 2016. Sex and strain-based inflammatory response to repeated tobacco smoke exposure in spontaneously hypertensive and Wistar Kyoto rats. Inhal. Toxicol. 28(14), 677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi WL, Zhang T, Zhou JR, Huang YH, Jiang CL. 2016. Rapid permissive action of dexamethasone on the regulation of blood pressure in a rat model of septic shock. Biomed. Pharmacother. 84, 1119–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LK, Cidlowski JA. 2010. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of healthy and malignant lymphocytes. Prog. Brain. Res. 182, 1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow SJ, Gordon CJ, Bass VL, Schladweiler MC, Ledbetter AD, Jarema KA, Phillips PM, Johnstone AF, Kodavanti UP. 2016. Age-related differences in pulmonary effects of acute and subchronic episodic ozone exposures in Brown Norway rats. Inhal. Toxicol. 28(7), 313–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow SJ, McGee MA, Henriquez A, Richards JE, Schladweiler MC, Ledbetter AD, Kodavanti UP. 2017. Respiratory Effects and Systemic Stress Response Following Acute Acrolein Inhalation in Rats. Toxicol. Sci. 158 (2), 454–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson EM, Vladisavljevic D, Mohottalage S, Kumarathasan P, Vincent R. 2013. Mapping acute systemic effects of inhaled particulate matter and ozone: multiorgan gene expression and glucocorticoid activity. Toxicol Sci 135, 169–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gool J, van Vugt H, Helle M, Aarden LA. 1990. The relation among stress, adrenalin, interleukin 6 and acute phase proteins in the rat. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 57(2), 200–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vida G, Peña G, Kanashiro A, Thompson-Bonilla M. del R, Palange D, Deitch EA, Ulloa L. 2011. β2-Adrenoreceptors of regulatory lymphocytes are essential for vagal neuromodulation of the innate immune system. FASEB J. (12), 4476–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas LR, Hoijman E, Beato M, Pecci A. 2008. Mechanisms involved in tissue-specific apopotosis regulated by glucocorticoids. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 109(3–5), 273–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang H, Su C, Chen J, Zhu B, Zhang H, Xiao H, Zhang J. 2014. Dexamethasone ameliorates H2S-induced acute lung injury by alleviating matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 expression. PLoS One. 9(4), e94701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward WO, Ledbetter AD, Schladweiler MC, Kodavanti UP. 2015. Lung transcriptional profiling: insights into the mechanisms of ozone-induced pulmonary injury in Wistar Kyoto rats. Inhal. Toxicol. 27 Suppl. 1, 80–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J, Higgins D, Hutting H, Serkova N, Baird C, Khailova L, Queensland K, Vu Tran Z, Weitzel L, Wischmeyer PE. 2013. Early propranolol treatment induces lung heme-oxygenase-1, attenuates metabolic dysfunction, and improves survival following experimental sepsis. Crit. Care. 17(5), R195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Xu M, Zhang Y, Guo Y, Zhang Y, He B. 2014a. Effects of long-term application of metoprolol and propranolol in a rat model of smoking. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 41(9), 708–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Yan J, Liang H, Jiang J. 2014b. Epinephrine enhances the response of macrophages under LPS stimulation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 254686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]