Highlights

-

•

As of July 14, 2015, the South Korean outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection has involved 185 secondary infections belonging to three overlapping generations of cases who have contracted the virus almost exclusively in the healthcare environment.

-

•

Fomite transmission may explain a significant proportion of the infections occurring in the absence of direct contact with infected cases.

-

•

The analysis of publicly available data collected from multiple sources, including the media, is useful for describing the epidemic history of an infectious disease outbreak.

Keywords: MERS, Coronavirus, Infectious diseases outbreaks, Epidemiology

Summary

Background

In May 2015, South Korea reported its first case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in a 68-year-old man with a history of travel in the Middle East. In the presence of secondary infections, an understanding of the transmission dynamics of the virus is crucial. The aim of this study was to characterize the transmission chains of MERS-CoV infection in the current South Korean outbreak.

Methods

Individual-level data from multiple sources were collected and used for epidemiological analyses.

Results

As of July 14, 2015, 185 confirmed cases of MERS have been reported in the Korean outbreak. Three generations of secondary infection, with over half belonging to the second generation, could be delineated. Hospital infection was found to be the most important cause of virus transmission, affecting largely non-healthcare workers (154/184). Healthcare switching has probably accounted for the emergence of multiple generations of secondary infection. Fomite transmission may explain a significant proportion of the infections occurring in the absence of direct contact with infected cases.

Conclusions

Publicly available data from multiple sources, including the media, are useful to describe the epidemic history of an outbreak. The effective control of MERS-CoV hinges on the upholding of infection control standards and an understanding of health-seeking behaviours in the community.

1. Introduction

Since its discovery in Saudi Arabia in mid-2012, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) has continued to be reported following exposure to infected camels and human contact in the healthcare setting, almost exclusively in Middle Eastern countries. There have, however, been subsequent reports of virus transmission outside the Arabian Peninsula in the 3 years since (Iran, Tunisia, UK, France, Italy, and USA).1 Globally, since September 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been notified of 1368 laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection, including at least 490 related deaths.2

On May 20, 2015, South Korea reported its first confirmed case of MERS-CoV infection in a 68-year-old man who had a history of travel in the Middle East,3 which was followed by chains of secondary infection. As of July 14, 2015, a total of 186 MERS-CoV cases, including 36 deaths, have been reported to the WHO.2 MERS-CoV infection is of particular concern worldwide, not just because of its similarity to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) that hit Hong Kong and other countries in 2003, but also the importance of translating former lessons to improve infectious disease control. As tertiary, quaternary, and quinary spread of MERS-CoV have been described in outbreaks in the Middle East,4 an understanding of the transmission dynamics of MERS-CoV in the current outbreak would contribute to the epidemiological knowledgebase for future reference.

The aim of this study was to characterize the transmission chains of MERS-CoV infection in the current South Korean outbreak, using publicly available data.

2. Methods

Individual-level data on infected patients from multiple sources were collected, matched, and collated to develop epidemiological analyses. These open access data sources included the following: World Health Organization updates (http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/en/), ProMED-mail (http://www.promedmail.org/), Centre for Health Protection updates (http://www.chp.gov.hk), and FluTrackers (https://flutrackers.com).

3. Results

As of July 14, 2015, 185 confirmed cases of MERS (mean age 54.6 years, male to female ratio 1.6:1) have been reported in South Korea (excluding one diagnosed in China). Secondary cases were classified as first-generation infections if there was a history of direct contact with the index patient (through visiting or the provision of care), or exposure in the same healthcare environment where the index patient was clinically managed. Similarly, second-generation infections refer to those with exposure to first-generation patients.

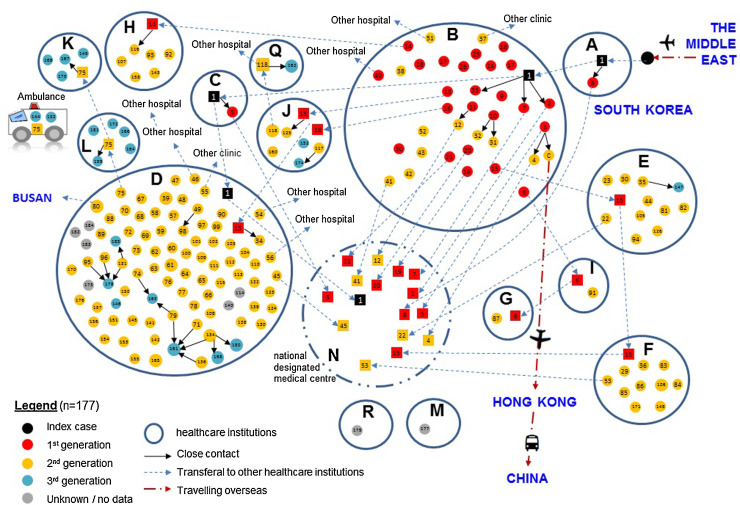

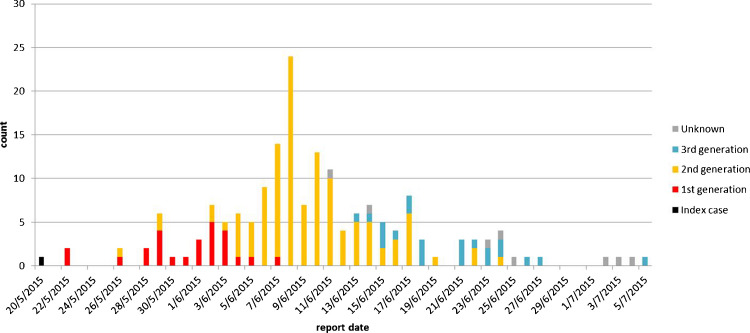

Of the 86 healthcare institutions that have taken in MERS-CoV-infected patients, local transmission has occurred in 13 (plus an ambulance), as shown in Figure 1 . A majority of the transmitted infections have been reported from two hospitals, accounting for 19.5% (n = 36) and 48.4% (n = 89) of all cases. Of note, 99 patients could not give a definitive history of direct contact with any infected persons, but had been staying in the same clinical environment with known case(s). Three generations of secondary infection could be delineated over time: first-generation (n = 26), second-generation (n = 120), and third-generation (n = 22); eight patients could not be classified. Three overlapping waves of transmission could be seen on the epidemic curve (Figure 2 ).

Figure 1.

Chain transmission of reported MERS-CoV cases in South Korea as differentiated by the respective generations of secondary infection (as of July 14, 2015) and location, i.e. the healthcare institutions, with solid circles (● in different colours) representing incident cases who contracted the virus from source patients (■ solid squares in different colours) who were infected before transfer to the implicated institution. Letters A to I denote hospitals, while the numbers (1–177) are codes given to each case, after excluding 9 unclassified ones. The National Designated Medical Centre ‘N’ was set up by the Government to take in confirmed MERS cases.

Figure 2.

Epidemic curve showing the reported numbers of cases by generation (n = 177, excluding unclassified cases) against time, as of July 14, 2015.

Mapping highlighted a number of characteristics of the outbreak. Firstly, infection within households was distinctly uncommon, accounting for only one first-generation case (wife of the index patient). Hospital infection was found to be the most important cause of the outbreak, but affected largely non-healthcare workers (154/184 from the collected data); there has been no reported community spread. Secondly, the transmissions appear to have been multifocal as a result of infected patients attending more than one institution during the course of their illness. Two cases, including the index case, were reported to have visited four healthcare institutions, while three had visited three. This can be explained by the phenomenon of healthcare switching, a practice that is common in South Korea, where many adult patients may use hospital performance information to choose the service providers.5, 6 This practice, coupled with the courtesy of visiting relatives in hospitals, appears to have fuelled the rapid dissemination of the virus. Thirdly, while MERS-CoV is known to spread by droplet transmission upon prolonged exposure to and within a short distance of source patients, direct contact could only be inferred in about 10% of the cases. It was found that the majority occurred instead in people who had shared the same healthcare environment. Fomite transmission is a possibility, as MERS-CoV has been shown to remain viable on inanimate surfaces, even after an extended interval of 48 h.7 Similarly SARS-CoV RNA has been collected from hospital surfaces days after their deposition by infected patients, although the viability of this virus could not be confirmed.8 Fomite transmission was the probable explanation for the transmission of SARS-CoV to passengers not in physical proximity to the source patient on an aircraft,9 an observation that could be extrapolated to MERS-CoV in visitors to hospitals in South Korea.

4. Discussion

Data collected from different publicly available sources, including the media, are useful to describe the epidemic history of the Korean MERS-CoV outbreak, which has affected multiple healthcare institutions. The analysis could be conducted readily without relying on the lengthy process of consulting official surveillance reports. A similar approach has also enabled another research group to report their preliminary assessment of the outbreak, an effort that would not have been possible before the internet era.10 There is, inevitably, the limitation of the validity of the epidemiological characteristics of each reported case, although much effort was made to verify the data in the course of the study. In fact the demographic profile of cases in the present study is similar to that subsequently released by the South Korean Ministry of Health (in Korean, machine translated, edited: http://www.mw.go.kr/front_new/al/sal0301ls.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403). Overall, the present results suggest that effective control of MERS-CoV hinges on the upholding of infection control standards to minimize the emergence of new generations of the virus and on advising the avoidance of healthcare switching when there is a suspected infection.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms Mandy Li for the skilful collation of the MERS data. Li Ka Shing Institute of Health Sciences is acknowledged for the technical support rendered to the development of the epidemiological analyses.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by the authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of The Chinese University of Hong Kong with which the authors are affiliated.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. The study was not supported by any funding grant.

Corresponding Editor: Eskild Petersen, Aarhus, Denmark

References

- 1.Zumla A., Hui D.S., Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60454-8. Epub 2015 June 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; Geneva: May 24 2015. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—Republic of Korea. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/don/14-july-2015-mers-korea/en/ (accessed July 15, 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hui D.S., Perlman S., Zumla A. Spread of MERS to South Korea and China. Lancet Respir Med. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00238-6. Epub 2015 June 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishiura H., Miyamatsu Y., Chowell G., Saitoh M. Assessing the risk of observing multiple generations of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) cases given an imported case. Euro Surveill. 2015;20 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.27.21181. pii: 21181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin J.Y., Choi N.K., Jung S.Y., Kim Y.J., Seong J.M., Park B.J. Overlapping medication associated with healthcare switching among Korean elderly diabetic patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:1461–1468. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.11.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang H.Y., Kim S.J., Cho W., Lee S. Consumer use of publicly released hospital performance information: assessment of the National Hospital Evaluation Program in Korea. Health Policy. 2009;89:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Munster V.J. Stability of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under different environmental conditions. Euro Surveill. 2013;18 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.38.20590. pii: 20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowell S.F., Simmerman J.M., Erdman D.D., Wu J.S., Chaovavanich A., Javadi M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus on hospital surfaces. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:652–657. doi: 10.1086/422652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen S.J., Chang H.L., Cheung T.Y., Tang A.F., Fisk T.L., Ooi S.P. Transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome on aircraft. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2416–2422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowling B.J., Park M., Fang V.J., Wu P., Leung G.M., Wu J.T. Preliminary epidemiological assessment of MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea, May to June 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.25.21163. pii: 21163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]