Abstract

Several bacteria and viruses remodel cellular membranes to form compartments specialised for replication. Bacteria replicate within inclusions which recruit membrane vesicles from the secretory pathway to provide nutrients for microbial growth and division. Viruses generate densely packed membrane vesicles called viroplasm which provide a platform to recruit host and viral proteins necessary for replication. This review describes examples where both intracellular bacteria (Salmonella, Chlamydia and Legionella) and viruses (picornaviruses and hepatitis C) recruit membrane vesicles to sites of replication by modulating proteins that control the secretory pathway. In many cases this involves modulation of Rab and Arf GTPases.

Keywords: Sites of virus replication, Replication in bacterial inclusions, RAb and Arf GTPAses, Secretory pathway

1. Introduction

Many intracellular pathogens replicate in specialised compartments in cells. For bacteria these are generally described as vacuoles or inclusions, and for viruses they are called virus factories or viroplasm (Fig. 1 ). The formation of replication sites can involve extensive modification of membrane compartments. Early changes probably reflect the mobilisation of cellular defences against infection such as phagocytosis and autophagy [1], [2] while later stages indicate the steps taken by the pathogen to avoid cellular defences and generate a compartment specialised for replication. Intracellular bacteria remain within membrane-bound vacuoles to avoid delivery to lysosomes and then recruit vesicles from the secretory pathway to provide nutrients necessary for microbial growth and cell division. Many viruses generate densely packed membrane vesicles to shield them from recognition by cellular defence pathways that recognise double-stranded RNA, and at the same time the membranes provide a platform to recruit viral and host proteins required for replication [3], [4], [5]. This review describes how recent work on intracellular bacteria such as Salmonella, Chlamydia and Leigionella draws parallels with studies on (+) strand RNA viruses where microbial proteins recruit membranes by modulating proteins that control the secretory pathway. In many cases this involves modulation of Rab and Arf GTPases.

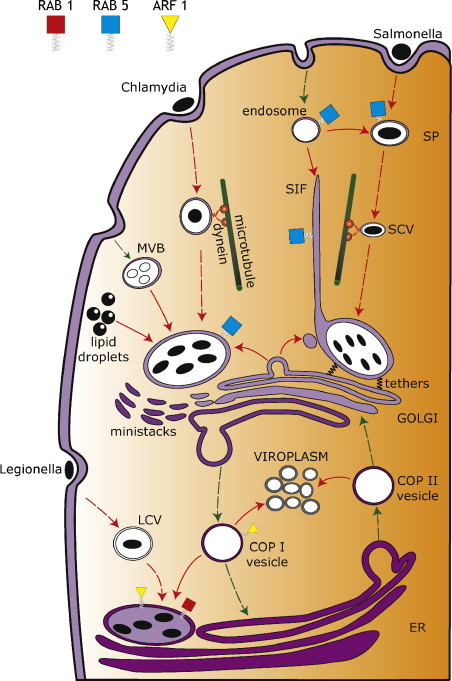

Fig. 1.

Replication compartments formed by bacteria and viruses. Salmonella-containing vacuoles interact with the endocytic pathway while migrating along microtubules. After reaching a peri-Golgi position, the vacuoles generate long membrane filaments (Sifs) and initiate replication. Legionella and Chlamydia escape interaction with the endosomal/lysosomal pathway. Chlamydia inclusions migrate along microtubules and replicate next to a fragmented Golgi. Legionella-containing vacuoles attach to ER and Golgi-derived vesicles and replication begins following fusion of vacuoles with the ER. Picornaviruses and hepatitis C replicate within perinuclear arrays of densely packed membrane vesicles called viroplasm. ER: endoplasmic reticulum; MVB: multivesicular bodies; SCVs: Salmonella-containing vacuoles; SIF: Salmonellainduced filaments; SP: spacious phagosome; LCV: Legionella-containing vacuole.

1.1. Small GTPases regulate formation of vesicles in the secretory pathway

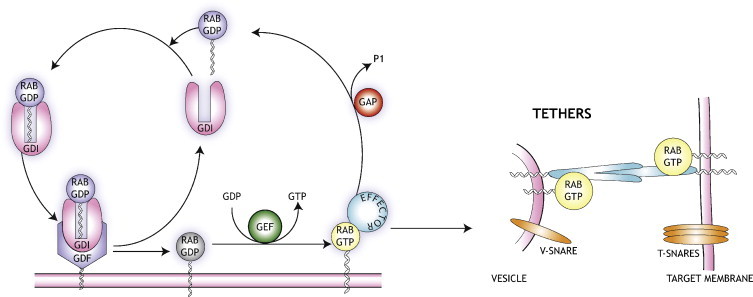

The Rab and Arf families of small GTPases act as molecular switches which regulate the formation, docking and fusion of membrane vesicles that carry cargo from one membrane compartment to another (Fig. 2 ). Vectorial transport through the secretory pathway is maintained because different organelles recruit different GTPases and specific tethering proteins able to direct interactions between transport vesicles and acceptor membranes. Vesicle fusion is consolidated by pairing between SNARE proteins [6], [7]. The Arf1 GTPase regulates the formation of COPI coated vesicles which form at Golgi membranes to carry cargo back to the ER. COPII coated vesicles assemble at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and carry proteins and lipids to the ERGIC and Golgi where docking and fusion are controlled by Rab1 and Golgi tethering proteins such as p115, GM130 and Golgin-84. The functions of other Rab proteins are described when they appear in the text.

Fig. 2.

Role of Rab and Arf proteins in directing vesicle transport. The small GTPases are held in the cytosol as inactive GDP-forms by GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI) proteins. Translocation to membranes requires membrane-bound GDI displacement factors (GDFs) which release the GTPase and expose a C-terminal lipid group for membrane binding. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) exchange GDP for GTP and allow the activated GTPase to bind effector proteins which facilitate vesicle budding and fusion. The cycle is completed by GTP-hydrolysis, which requires GTPase activating proteins (GAPs), followed by extraction of the GDP-bound enzyme from the membrane by GDI.

2. Bacteria replicate within membrane-bound inclusions and vacuoles

2.1. Role of Rab GTPases during Golgi positioning of Salmonella-containing vacuoles

Salmonella enterica enters the cell within a membrane compartment known as the spacious phagosome (SP), which then shrinks to enclose one or two bacteria within Salmonella-containing vacuoles (SCVs) [8], [9], [10]. Early SP and SCV maturation result in recruitment of Rab 5 and several Rab5 effector proteins which normally control endocytosis. Sorting nexins may facilitate shrinkage of the SP [11] during formation of the SCV, while Rab5 effectors such as early endosome antigen 1 prime the SCV for progress along the endocytic pathway. SCV lose Rab5 and accumulate Rab7, LAMP1 and acidify. Rab7 recruits Rab7-interacting lysosomal protein (RILP) which links the SCV to the dynein motor protein allowing movement to the Golgi and MTOC [12]. This, coupled with acidification of the vacuole, activates secretion of bacterial Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2) proteins which are needed for continued Golgi positioning and replication. The Pip2B and SifA proteins recruit host kinesin interacting protein SKIP to the SCV to displace kinesin and inhibit outward movement [13], [14]. SifA may also impair the Rab7-RILP interaction to release dynein [12]. SseF and SseG locate to the surface of the vacuole where they may tether the vacuoles to the Golgi [15], [16]. Golgi positioning may also involve SipA and SifA proteins, actin [17], and recruitment of myosin II [18].

Golgi positioning appears to be crucial for replication [19] and is thought to facilitate the supply of nutrients from Golgi-derived vesicles. The exact pathway followed by the vesicles remains to be determined. Vacuoles recruit 18 different RabGTPases during maturation [20] showing complex interaction with the secretory pathway. Vesicles leaving the trans-Golgi network (TGN) accumulate next to the SCV, but do not appear to fuse [21], making it unclear whether they deliver nutrients. Interestingly, long thin tubules of membrane called Salmonella induced filaments (Sifs) containing endosomal and lysosomal markers extend from the SCVs soon after positioning at the Golgi. Sifs require secretion of SPI-2 proteins, SseF and SseG, and extend towards the cell periphery along microubules where they recruit Rab9 and Rab11 and take up fluid phase endocytic markers [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. Sifs may provide nutrients to bacteria from outside the cell by fusing with vesicles trafficking between late endosomes and the Golgi.

2.2. Bacterial effector proteins recruit of Rab GTPases and SNARE proteins to Chlamydia inclusions

Chlamydia invades the cell as an infectious, but replication defective, elementary body (EB) and differentiates into a replicative form called the reticulate body (RB), within a membrane compartment called an “inclusion”. Chlamydia does not interact with the endosomal/lysosomal pathway [25] but, as seen for Salmonella, the inclusions recruit dynein and migrate along microtubules to a peri-Golgi position [26], and again peri-Golgi positioning at the MTOC is required for replication. Inclusions receive sphingomyelin and cholesterol from exocytic vesicles that would normally deliver lipids from the TGN to the plasma membrane [27], [28], [29], [30] and can also gain lipids directly from lipid storage organelles called lipid droplets. This involves the bacterial Lda3 protein which may link lipid droplets to the outer surface of the inclusion [31]. Chlamydia infection also results in proteolysis of tethering protein Golgin 84 by caspases leading to fragmentation of the Golgi into ministacks. Inhibition of Golgi fragmentation reduces replication and also prevents the delivery of lipids to the inclusion suggesting that fragmented Golgi ministacks provide vesicles able to fuse with the vacuole [32]. Non-lipid nutrients can also be delivered to Chlamydia inclusion by endocytosis and fusion with multivesicular bodies (MVB) [33].

Chlamydia effector proteins called ‘integral inclusion membrane’ (Inc) proteins recruit several RabGTPases to the inclusions [34]. Mature inclusions recruit Rab4 and Rab11 [35], [36], which are generally present in recycling endosomes and could interact with incoming MVBs. Inclusions recruit Rab1, which may activate tethering and subsequent fusion with Golgi-derived vesicles or ministacks. Rab6 and Rab10, which are involved in Golgi trafficking, are associated with inclusions in a species-dependent manner [35]. Rab recruitment requires the GTP-bound form suggesting that the Inc proteins act as Rab effector proteins. Inc protein Cpn0585, has coiled coil domains that share sequence similarity with Rab effectors such as the tethering proteins Golgin 84 and Golgi matrix protein GM130, and interacts with Rab1, Rab10 and Rab11 [37]. Whether Cpn0585 plays a role in Golgi fragmentation seen during infection has not been tested. IncA proteins such as CT813 have SNARE motifs and interact directly with host SNAREs that facilitate vesicle fusion [38]. The glutamate residue in the SNARE-like motif of IncA suggests similarity with Q-SNAREs that would interact with R-SNAREs. This is consistent with co-precipitation of Vamp3, Vamp7 and VAMP8 with IncA, and location of Vamp8 in the inclusion membrane. The precise role the SNARE homologues play in inclusion formation is not known. They interact with SNAREs involved in endosome trafficking and may aid recruitment of MVBs to the inclusion.

2.3. Bacterial effector proteins modulate Rab1 and Arf1 during maturation and fusion of Legionella-containing vacuoles with endoplasmic reticulum

Legionella pneunomophila is an intracellular bacterium of amoeba but can infect humans following inhalation of aerosols from contaminated water and air cooling systems. Inhaled bacteria infect alveolar macrophages and become surrounded by a membrane compartment called the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV), which avoids interactions with the endosomal/lysosomal pathway [39]. The LCVs quickly recruit Arf1 and Rab1 GTPases, and associate with vesicles containing ER and ERGIC markers, suggesting recruitment of vesicles trafficking between ER and Golgi compartments. Membrane vesicles remain associated with the LCV for several hours during which time the LCVs lose Rab1 and Arf1 [40], [41]. The vesicles tethered to the LCV [42] eventually fuse with the vacuole and deliver ER markers, and this is coincident with the onset of replication. Delivery is inhibited by Brefeldin-A, and a dominant negative Sar1[H79G] GTPase slows bacterial replication, suggesting involvement of COPI and COPII transport vesicles [42].

Rabs are recruited to the LCV by bacterial effector proteins DrrA (also called SidM) and LepB [43]. DrrA first acts as a Rab1-specific GDF recruiting Rab1 onto the cytosolic face of the LCV membrane [44], [45]. DrrA then acts as a Rab-GEF protein promoting GDP-GTP exchange to preserve Rab1 in its active form [43], [46]. The LepB protein binds the LCV at later times and is also present on mature LCVs that have acquired ER markers. LepB binds activated Rab1-GTP and acts as GAP [44] leading to release of Rab1 from the vacuole and this is coincident with fusion of the vacuole with ER-derived vesicles. DrrA and LepB show exclusive binding to Rab1, but Dot/Icm effector LidA binds Rab1, Rab6 and Rab8 [43]. LidA does not have GAP or GEF activity and cannot affect GTP hydrolysis, but works with DrrA/SidM to recruit Rab1 to vacuoles [43].

The presence of Arf1 and Rab1 could facilitate fusion with both ER and Golgi-derived membranes. Rab1 may interact with effector proteins such as p115 or the GM130/Grasp65 complex would normally tether COPI and COPII vesicles to the cis-Golgi. Silencing experiments suggest that the TRAPP1 tethering complex, which facilitates docking of COPII vesicles to ERGIC and Golgi membranes, and Sec22b, which is a v-SNARE found in ER to Golgi transport vesicles are both required for replication [47], [48], [49]. These results suggest that COPII vesicles deliver the host factors required to sustain microbial growth and cell division within the ER-derived vacuole.

3. Viruses generate densely packed membranes for replication

The (+) strand RNA viruses produce replicase proteins with RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and helicase activity which are targeted to the cytoplasmic face of the ER by non-structural proteins with membrane binding motifs. This invariably results in the generation of densely packed membrane vesicles called viroplasm. Work in this area has concentrated on understanding how these vesicles are formed, and how their use as replication sites impacts on the secretory pathway. Multiple interactions between replicase proteins probably induce the membrane curvature required to generate vesicles in a way that parallels virus budding from membranes [4], [50]. Virus replication can, however, slow secretion suggesting that the formation of viroplasm may divert vesicles normally involved transport between the ER and Golgi into the replication complex. As described above for bacteria, this can involve modulation of small GTPases.

3.1. Role of Arf1 and Arf-GEF proteins in modulating membrane traffic during picornavirus replication

A search for a link between virus replication and membrane trafficking proteins was stimulated by the observation that BFA blocks replication of enteroviruses such as poliovirus and coxsackieviruses [51]. BFA inhibits Arf-GTP exchange proteins (Arf-GEFS) and reduces the Arf1-GTP needed to generate COPI coats in the Golgi. Inhibition of replication by BFA has led to a model where viral activation of Arf-GEFs would recruit Arf1, and Arf effector proteins, needed to recruit membranes into replication compartments [52]. This is supported by genome-wide interference screens where COPI proteins are important for replication of both animal and plant picornaviruses [53], [54], and is consistent with the increase in Arf-GTP levels seen in cells following poliovirus infection. Moreover, Arf-1 and Arf-GEF proteins GBF1 and BIG1/2 are recruited into replication complexes [55], [56], and poliovirus replication is inhibited by siRNA for GBF1 [57]. Sequestration of Arf-1 into the replication complex would also explain the block in secretion seen in infected cells [58].

For poliovirus, secretion is blocked by the 3A protein which tethers the replicase to ER membranes. 3A does not have intrinsic Arf-GEF activity but the 3A protein recruits Arf-GEFs such as GBF1 and BIG1/2 to membranes, and 3A activates Arf-GEF activity ‘in vitro’ [56]. This provides an explanation for inhibition of poliovirus replication by BFA, and how the sequestration of Arf1 and Arf-Gefs into replication sites, could block secretion. Evidence that this generates densely packed vesicles is less clear. 3A alone cannot generate the vesicles, and recruitment of Arf-GEFs by 3A is not essential for replication [57]. Moreover, BFA does not prevent formation of densely packed vesicles by poliovirus, so vesicle formation does not require activated Arf-GEF proteins [57].

An alternative mechanism of action for 3A is provided from coxsackievirus, which is also a BFA-sensitive enterovirus. The coxsackievirus 3A protein inhibits Arf-GEF activity, and reduces Arf-GTP [59], [60], [61] and may inhibit ER to Golgi transport by stabilizing ARF1-GDP-GBF1 complexes which would in turn reduce the supply of Arf1-GTP for COPI coats. 3A may also slow secretion by inactivating LIS1, a component of the dynein–dynactin motor complex [62] and contribute to microtubule-dependent disruption of the Golgi apparatus seen during poliovirus infection [63]. These experiments explain how 3A would slow secretion, but again do not provide a mechanism for generation of the densely packed vesicles, or paradoxically, explain why the virus would be sensitive to BFA.

Several picornaviruses families are resistant to BFA, and their 3A proteins do not slow ER to Golgi transport [60], [64], [65]. For these viruses COPII coated vesicles may provide membranes for replication [66], [67], [68], [69] while other studies implicate a role for autophagosomes [70]. In the case of Foot-and-Mouth Disease virus, secretion is blocked by the ER-tethered 2BC protein [65], [71], rather than 3A, and although less well studied, the 2B and 2BC of enteroviruses also slow secretion when expressed alone in cells [58], [72]. These proteins can therefore affect membrane traffic and for 2C this may involve binding to ER membrane protein reticulon 3, which is involved in ER to Golgi trafficking and is required for replication [73].

3.2. Recruitment of membrane trafficking proteins to membrane webs formed from the endoplasmic reticulum during replication of hepatitis C virus

Hepatitis C virus replication occurs within a web of ER membranes. The NS5A protein is anchored to the cytoplasmic face of the web and recruits the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, NS5B. Both NS5A and NS5B bind VAMP associated proteins (VAPs) [74], [75]. NS5B binds to a coiled coil domain (CCD) in VAP that resembles the CCD of SNARE proteins. Silencing VAP-B reduces the stability of NS5B, and depletion of VAP-B from cell free assays reduces RNA replication. Current models suggest that a VAPA/B heterodimer forms a scaffold that supports the replication complex. VAP proteins also bind to SNAREs involved in ER to Golgi transport, making it is possible that the VAP scaffold also facilitates membrane fusion to generate the membrane web from the ER. This may be true for other (+) strand RNA viruses such as Norwalk virus where membrane-bound nsp48 also binds VAP-A [76].

NS5A also binds TBC1D20, a Rab1-GAP protein, and both TBC1D20 and NS5A co-localise with ER markers. TBC1D20 activates Rab1 GTP hydrolysis, and since depletion of TBC1D20 and Rab1 greatly reduce HepC replication [77], [78] it is likely that activation of Rab1-GTP is in some way involved in virus infection. Local blockade of Rab1 could, for example direct transport vesicles to make membrane webs. Rab5 is also recruited to the replication complex [79] by binding to NS4B, and virus-induced membranes recruit Rab5 effectors EEA1, rabaptin 5 and Rab4 suggesting the web may fuse with endosomes. A functional role for Rab5 in viral genome replication is suggested because dominant negative Rab5 reduces replication of replicons, and partial silencing of Rab5 reduces synthesis of viral RNA.

4. Conclusions

The studies described above set the stage or further work where it will be important to analyse interactions between host and microbial proteins at a structural level, and see how these interactions contribute to virulence and/or immune evasion. The work also provides a precedent for studies on other pathogens that use membrane compartments for replication. Brucella for example, traffic through lysosomes before fusing with the ER [80], and Coxiella replicate in a spaceous parasitophorous vacuole formed from secondary lysosomes [81]. Recent work on coronaviruses draws parallels with poliovirus where SARS-CoV replicates within densely packed membranes [82], and mouse hepatitis virus shows sensitivity to BFA and requires GBF1 mediated Arf1 activation [83], [84]. Disruption or use of the Golgi is not restricted to the (+) strand RNA viruses. The negative strand RNA Bunyaviruses replicate in the Golgi apparatus where they form tubes that contain replicase proteins [85]. The large DNA viruses such as Fowlpox encode homologues of SNAP proteins involved in SNARE pairing [86], while African Swine Fever virus replicates at the MTOC, slows secretion, and causes Golgi fragmentation and microtubule-dependent loss of the TGN [87]. ASFV also encodes a multigene family of proteins with C-terminal KEDL sequences able to interfere with KDEL-receptor mediated ER to Golgi trafficking and redistribute ER proteins to the ERGIC [88]. In all these cases the consequences of modulating the early secretory pathway in the context of virus survival and/or pathogenesis remain to be discovered.

References

- 1.Kirkegaard K., Taylor M.P., Jackson W.T. Cellular autophagy: surrender, avoidance and subversion by microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:301–314. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wileman T. Aggresomes and autophagy generate sites for virus replication. Science. 2006;312:875–878. doi: 10.1126/science.1126766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Netherton C., Moffat K., Brooks E., Wileman T. A guide to viral inclusions, membrane rearrangements, factories, and viroplasm produced during virus replication. Adv Virus Res. 2007;70:101–186. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(07)70004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller S., Krijnse-Locker J. Modification of intracellular membrane structures for virus replication. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:363–374. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenzie J. Wrapping things up about virus replication. Traffic. 2005;6:967–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grosshans B.L., Oritz D., Novick P. Rabs and their effectors: achieving specificity in membrane traffic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11821–11827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai H., Reinisch K., Ferro-Novick S. Coats, tethers, Rabs, and SNAREs work together to mediate the intracellular destination of a transport vesicle. Dev Cell. 2007;12:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramsden A.E., Holden D.W., Mota L.J. Membrane dynamics and spatial distribution of salmonella-containing vacuoles. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakowski M.A., Braun V., Brumell J.H. Salmonella-containing vacuoles: directing traffic and nesting to grow. Traffic. 2008;9:2022–2031. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steele-Mortimer O. The Salmonella-containing vacuole: moving with the times. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bujny M.V., Ewels P.A., Humphrey S., Attar N., Jepson M.A., Cullen P.J. Sorting nexin-1 defines an early phase of Salmonella-containing vacuole-remodelling during Salmonella infection. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2027–2036. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison R.E., Brumell J.H., Khandani A., Bucci C., Scott C.C., Jiang X. Salmonella impairs RILP recruitment to Rab7 during maturation of invasion vacuoles. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3146–3154. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boucrot E., Henry T., Borg J.P., Gorvel J.P., Méresse S. The intracellular fate of Salmonella depends on the recruitment of kinesin. Science. 2005;308:1174–1178. doi: 10.1126/science.1110225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henry T., Couillault C., Rockenfeller P., Boucrot E., Dumont A., Schroeder N. The Salmonella effector protein PipB2 is a linker for kinesin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13497–13502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605443103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrahams G.L., Müller P., Hensel P. Functional dissection of SseF, a type III effector protein involved in positioning the salmonella-containing vacuole. Traffic. 2006;7:950–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramsden A.E., Mota L.J., Münter S., Shorte S.L., Holden D.W. The SPI-2 type III secretion system restricts motility of Salmonella-containing vacuoles. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2517–2529. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brawn L.C., Hayward R.D., Koronakis V. Salmonella SPI1 effector SipA persists after entry and cooperates with SPI2 effector to regulate phagosome maturation and intracellular replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasylnka J.A., Bakowski M.A., Szeto J., Ohlson M.B., Trimble W.S., Miller S.I. Role for myosin II in regulating positioning of Salmonella-containing vacuoles and intracellular replication. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2722–2735. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00152-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salcedo S.P., Holden D.W. SseG, a virulence protein that targets Salmonella to the Golgi network. EMBO J. 2003;22:5003–5014. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith A.C., Heo W.D., Braun V., Jiang X., Macrae C., Casanova J.E. A network of Rab GTPases controls phagosome maturation and is modulated by Salmonella enteritica serovar Typhimurium. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:263–268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhle V., Abrahams G.L., Hensel M. Intracellular Salmonella enterica redirect exocytic transport processes in a Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-dependent manner. Traffic. 2006;7:716–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drecktrah D., Knodler L.A., Howe D., Steele-Mortimer O. Salmonella trafficking is defined by continuous dynamic interactions with the endolysosome system. Traffic. 2007;8:212–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drecktrah D., Levine-Wilkinson S., Dam T., Winfree S., Knodler L.A., Schroder T.A. Dynamic behaviour of Salmonella-induced membrane tubules in epithelial cells. Traffic. 2008;9:2117–2129. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00830.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajashekar R., Liebl D., Seitz A., Hensel M. Dynamic remodelling of the endosomal system during formation of Salmonella-induced filaments by intracellular Salmonella enterica. Traffic. 2008;9:2100–2116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scidmore M.A., Fischer E.R., Hackstadt T. Restricted fusion of Chlamydia trachomatis vesicles with endocytic compartments during the initial stages of infection. Infect Immun. 2003;71:973–984. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.973-984.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grieshaber S.S., Grieshaber N.A., Hackstadt T. Chlamydia trachomatis uses host cell dynein to traffic to the microtubule-organizing center in a p50 dynamitin-independent process. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3793–3802. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hackstadt T., Scidmore M.A., Rockey D.D. Lipid metabolism in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected cells: directed trafficking of Golgi-derived sphingolipids to the chlamydial inclusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4877–4881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fields K.A., Hackstadt T. The chlamydial inclusion: escape from the endocytic pathway. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:221–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.012502.105845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carabeo R.A., Mead D.J., Hackstadt T. Golgi-dependent transport of cholesterol to the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6771–6776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131289100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore E.R., Fischer E.R., Mead D.J., Hackstadt T. The chlamydial inclusion preferentially intercepts basolaterally directed sphingomyelin-containing exocytic vacuoles. Traffic. 2008;9:2130–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00828.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cocchiaro J.L., Kumar Y., Fischer E.R., Hackstadt T., Valdivia R.H. Cytoplsmic lipid droplets are translocated into the lumen of the Chlamydia trachomatis parisitophorous vacuole. PNAS. 2008;105:9379–9384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712241105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heuer D, Lipinski AR, Machuy N, Karlas A, Wehrens A, Siedler F, et al. Chlamydia causes fragmentation of the Golgi compartmenmt to ensure reproduction. Nature 2008;2009;457:731–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Beatty W.L. Trafficking from CD63-positive late endocytic multivesicular bodies is essential for intracellular development of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:350–359. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valdivia R.H. Chlamydia effector proteins and new insights into chlamydial cellular microbiology. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rzomp K.A., Scholtes L.D., Briggs B.J., Whittaker G.R., Scidmore M.A. Rab GTPases are recruited to chlamydial inclusions in both a species-dependent and species-independent manner. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5855–5870. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5855-5870.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rzomp K.A., Moorhead A.R., Scidmore M.A. The GTPase Rab4 interacts with Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane protein CT229. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5362–5373. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00539-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cortes C., Rzomp K.A., Tvinnereim A., Scidmore M.A., Wizel B. Chlamydia pneumoniae inclusion membrane protein Cpn0585 interacts with multiple Rab GTPases. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5586–5596. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01020-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delevoye C., Nilges M., Dehoux P., Paumet F., Perrinet S., Dautry-Varsat A. SNARE protein mimicry by an intracellular bacterium. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000022. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy C.R., Berger K.H., Isberg R.R. Legionella pneumophila DotA protein is required for early phagosome trafficking decisions that occur within minutes of bacterial uptake. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:663–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kagan J.C., Roy C.R. Legionella phagosomes intercept vesicular traffic from endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:945–954. doi: 10.1038/ncb883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagai H., Kagan J.C., Zhu X., Kahn R.A., Roy C.R. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science. 2008;295:679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.1067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson C.G., Roy C.R. Attachment and fusion of endoplasmic reticulum with vacuoles containing leigonella pneumophila. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:793–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Machner M.P., Isberg R.R. Targeting of host Rab GTPase function by the intravacuolar pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Dev Cell. 2006;11:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ingmundson A., Delprato A., Lambright D.G., Roy C.R. Legionella pneumophila proteins that regulate Rab1 membrane cycling. Nature. 2007;450:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nature06336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machner M.P., Isberg R.R. A bifunctional bacterial protein links GDI displacement to Rab1 activation. Science. 2007;318:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1149121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murata T., Delprato A., Ingmundson A., Toomre D.K., Lambright D.G., Roy C.R. The Legionella pneumophila effector protein DrrA is a Rab1 guanine nucleotide-exchange factor. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:971–977. doi: 10.1038/ncb1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kagan J.C., Stein M.P., Pypaert M., Roy C.R. Legionella subvert the functions of Rab1 and Sec22b to create a replicative organelle. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1201–1211. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dorer M.S., Kirton D., Bader J.S., Isberg R.R. RNA interference analysis of Legionella in Drosophila cells: exploitation of early secretory apparatus dynamics. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e34. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Derré I., Isberg R.R. Legionella pneumophila replication vacuole formation involves rapid recruitment of proteins of the early secretory system. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3048–3053. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.3048-3053.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahlquist P. Parallels among positive strand RNA viruses, reverse transcribing viruses and double strand RNA viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:371–382. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maynell L.A., Kirkegaard K., Klymkowsky M.W. Inhibition of poliovirus RNA synthesis by brefeldin A. J Virol. 1992;66:1985–1994. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.1985-1994.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Belov G.A., Ehrenfeld E. Involvement of cellular membrane traffic proteins in poliovirus replication. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:36–38. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.1.3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cherry S., Kunte A., Wang H., Coyne C., Rawson R.B., Perrimon N. COPI activity coupled with fatty acid biosynthesis is required for viral replication. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang Y., Serviene E., Gal J., Panavas T., Nagy P.D. Identification of essential host factors affecting tombusvirus RNA replication based on the yeast Tet promoters Hughes collection. J Virol. 2006;80:7394–7404. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02686-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Belov G.A., Fogg M.H., Ehrenfeld E. Poliovirus proteins induce membrane association of GTPase ADP ribosylation factor. J Virol. 2005;79:7207–7216. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.7207-7216.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Belov G.A., Altan-Bonnet N., Kovtunovych G., Jackson C.L., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Ehrenfeld E. Hijacking components of the cellular secretory pathway for replication of poliovirus RNA. J Virol. 2007;81:558–567. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01820-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belov G.A., Feng Q., Nikovics K., Jackson C.L., Ehrenfeld E. A critical role of a cellular membrane traffic protein in poliovirus RNA replication. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000216. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doedens J.R., Kirkegaard K. Inhibition of cellular protein secretion by poliovirus proteins 2B and 3A. EMBO J. 1995;14:894–897. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wessels E., Duijsings D., Niu T.K., Neumann S., Oorschot V.M., de Lange F. A viral protein that blocks Arf-1 mediated COP-I assembly by inhibiting the guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. Dev Cell. 2006;11:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wessels E., Duijsings D., Lanke K.H.W., van Dooren S.H.J., Jackson C.L., Melchers W.J.G. Effects of picornavirus 3A proteins on protein transport and GBFI-dependent COP-I recruitment. J Virol. 2006;80:11852–11860. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01225-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wessels E., Duijsings D., Lanke K.H., Melchers W.J., Jackson C.L., Kuppeveld F.J. Molecular determinants of the interaction between coxsackievirus protein 3A and guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. J Virol. 2007;81:5238–5245. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02680-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kondratova A.A., Neznanov N., Kondratov R.V., Gudkov A.V. Poliovirus protein 3A binds and inactivates LIS1, causing block of membrane protein trafficking and deregulation of cell division. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1403–1410. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.10.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beske O., Reichelt M., Taylor M.P., Kirkegaard K., Andino R. Poliovirus infection blocks ERGIC-to-Golgi trafficking and induces microtubule-dependent disruption of the Golgi complex. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3207–3218. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choe S.S., Dodd D.A., Kirkegaard K. Inhibition of cellular protein secretion by picornaviral 3A proteins. Virol. 2005;337:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moffat K., Howell G., Knox C., Belsham G.J., Monaghan P., Ryan M.D. Effects of foot-and-mouth disease virus nonstructural proteins on the structure and function of the early secretory pathway: 2BC but not 3A blocks endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi transport. J Virol. 2005;79:4382–4395. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4382-4395.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gazina E.V., Mackenzie J.M., Gorell R.J., Anderson D.A. Differential requirements for COPI coats in formation of replication complexes among three genera of Picornaviridae. J Virol. 2002;76:11113–11122. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.11113-11122.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rust R.C., Landmann L., Gosert R., Tang B.L., Hong W., Hauri H.P. Cellular COPII proteins are involved in production of the vesicles that form the poliovirus replication complex. J Virol. 2001;75:9808–9818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9808-9818.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Egger D., Bienz K. Intracellular location and translocation of silent and active poliovirus replication complexes. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:707–718. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wei T., Wang A. Biogenesis of cytoplasmic membranous vesicles for plant potyvirus replication occurs at endoplasmic reticulum exit sites in a COPI- and COPII-dependent manner. J Virol. 2008;82(24):12252–12264. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01329-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jackson W.T., Giddings T.H, Jr., Taylor M.P., Mulinyawe S., Rabinovitch M., Kopito R.R. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. Plosbiology. 2005;3:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moffat K., Knox C., Howell G., Clark S.J., Yanh H., Belsham G.J. Inhibition of the secretory pathways by foot-and-mouth disease virus 2BC protein is reproduced by coexpression of 2B with 2C, and the site of inhibition is determined by the subcellular localisation of 2C. J Virol. 2007;81:1129–1139. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00393-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cornell C.T., Kiosses W.B., Harkins S., Whitton J.L. Inhibition of protein trafficking by coxsackievirus b3: multiple viral proteins target a single organelle. J Virol. 2006;80:6637–6647. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02572-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tang W.F., Yang S.Y., Wu B.W., Jeng J.R., Chen Y.L., Shih C.H. Reticulon 3 binds the 2C protein of enterovirus 71 and is required for viral replication. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5888–5898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tu H., Gao L., Shi S.T., Taylor D.R., Yang T., Mircheff A.K. Hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase and NS5A complex with a SNARE-like protein. Virology. 1999;263:30–41. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamamoto I., Nishimura Y., Okamoto T., Aizaki H., Liu M., Mori Y. Human VAP-B is involved in hepatitis C virus replication through interaction with NS5A and NS5B. J Virol. 2005;79:13473–13482. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13473-13482.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ettayebi K., Hardy M.E. Norwalk virus nonstructural protein p48 forms a complex with the SNARE regulator VAP-A and prevents cell surface expression of vesicular stomatitis virus G protein. J Virol. 2003;77(21):11790–11797. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11790-11797.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sklan E.H., Serrano R.L., Einav S., Pfeffer S.R., Lambright D.G., Glenn J.S. TBC1D20 is a Rab1 GTPase-activating protein that mediates hepatitis C virus replication. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(50):36354–36361. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sklan E.H., Staschke K., Oakes T.M., Elazar M., Winters M., Aroeti B. A Rab-GAP TBC domain protein binds Hepatitis C virus NS5A and mediates virus replication. J Virol. 2007;81:11096–11105. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01249-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stone M., Jia S., Heo W.D., Meyer T., Konan K.V. Participation of Rab5, an early endosome protein, in hepatitis C virus RNA replication machinery. J Virol. 2007;81:4551–4563. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01366-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Starr T., Ng T.W., Wehrly T.D., Knodler L.A., Celli J. Brucella intracellular replication requires trafficking through the late endosomal/lysosomal compartment. Traffic. 2008;9(5):678–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Voth D.E., Heinzen R.A. Lounging in a lysosome: the intracellular lifestyle of Coxiella burnetii. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:829–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Knoops K., Kikkert M., Worm S.H., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J.C., van der Meer Y., Koster A.J. SARS-coronavirus replication is supported by a reticulovesicular network of modified endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Verheije M.H., Raaben M., Mari M., Te Lintelo E.G., Reggiori F., van Kuppeveld F.J. Mouse hepatitis coronavirus RNA replication depends on GBF1-mediated ARF1 activation. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000088. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oostra M., te Lintelo E.G., Deijs M., Verheije M.H., Rottier P.J., de Haan C.A. Localization and membrane topology of coronavirus nonstructural protein 4: involvement of the early secretory pathway in replication. J Virol. 2007;81(22):12323–12336. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01506-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fontana J., López-Montero N., Elliott R.M., Fernández J.J., Risco C. The unique architecture of Bunyamwera virus factories around the Golgi complex. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10(10):2012–2028. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Laidlaw S.M., Anwar M.A., Thomas W., Green P., Shaw K., Skinner M.A. Fowlpox virus encodes nonessential homologs of cellular alpha-SNAP, PC-1, and an orphan human homolog of a secreted nematode protein. J Virol. 1998;72:6742–6751. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6742-6751.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Netherton C.L., McCrossan M., Denyer M., Ponnambalam S., Armstrong J., Takamatsu H.H. African Swine Fever virus causes microtubule-dependent dispersal of the trans-Golgi network and slows delivery of membrane protein to the plasma membrane. J Virol. 2006;80:11385–11392. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00439-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Netherton C., Rouiller I., Wileman T. The subcellular distribution of multigene family 110 proteins of African Swine Fever virus is determined by differences in C-terminal KDEL endoplasmic reticulum retention motifs. J Virol. 2004;78:3710–3721. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3710-3721.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]