Abstract

Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are at increased risk for alcohol use disorder (AUD), in part due to the use of alcohol as a coping strategy. High quality romantic relationships can buffer individuals against risk for psychopathology; however, no studies have evaluated romantic relationship quality in risk for PTSD-AUD in non-clinical samples. The current study examined the main and interactive effects of PTSD symptoms and romantic relationship quality on alcohol consumption (i.e., past 30-day alcohol use quantity, frequency, and binge frequency) and alcohol-related consequences in a sample of 101 college students (78.2% women) with a history of interpersonal trauma (i.e., physical/sexual assault, excluding intimate partner violence) who reported being in a romantic relationship. Relationship quality significantly moderated the association between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol use quantity (B = −0.972, p = .016) and alcohol-related consequences (B = −0.973, p = .009), such that greater PTSD symptoms were associated with greater alcohol use quantity and consequences among those low, but not high, in relationship quality. The interaction between PTSD symptom severity and relationship quality in relation to binge drinking was marginally significant (B = −0.762, p = .063), and relationship quality did not significantly moderate the association between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol use frequency. The main effect of PTSD symptom severity was significantly associated with alcohol-related consequences, but no other alcohol outcomes; the main effect of relationship quality was not associated with alcohol use outcomes or consequences. High quality romantic relationships may serve as a buffer for young adults at risk for alcohol problems.

Keywords: College students, Trauma, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Relationship quality, Alcohol use

1. Introduction

Young adulthood is a developmentally sensitive time for developing alcohol use disorder (AUD) symptomology (Hingson, Heeren, & Winter, 2006; Jackson & Sartor, 2016; Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005; Li, Hewitt, & Grant, 2004). This pattern of emergence can be largely attributed to the high prevalence of risky drinking behaviors, such as heavy episodic (binge) drinking and heavy alcohol use during this developmental period (Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Jackson & Sartor, 2016; Mahalik et al., 2013). Indeed, recent data from the National Epidemiologic Survey for Alcohol and Related Conditions indicate that the mean age of onset for any AUD is 26.2 years, with severe AUD presenting even earlier (Mage = 23.9 years; Grant et al., 2015). Furthermore, young adults enrolled in college are at even greater risk for developing alcohol use problems and AUD (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, Schulenberg, & Miech, 2014; O’Malley & Johnston, 2002; Slutske, 2005; Slutske et al., 2004), as compared to their non-enrolled, same-age peers. Therefore, studies of risk and protective factors for risky alcohol use in college populations are particularly useful.

One identified risk marker for alcohol misuse and AUD in college-aged young adults is interpersonal trauma. Exposure to interpersonal potentially traumatic events (e.g., physical and sexual assault/abuse) is associated with increased risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995), elevated alcohol use (i.e., frequency and quantity; Berenz, Cho et al., 2016; Overstreet, Berenz, Kendler, Dick, & Amstadter, 2017), and alcohol use problems (Rice et al., 2001; Volpicelli, Balaraman, Hahn, Wallace, & Bux, 1999). Risky alcohol use may result from the motivation to use alcohol as a means to cope with negative affect and trauma-related memories (O’Hare & Sherrer, 2011; Waldrop, Back, Verduin, & Brady, 2007). Increases in alcohol use following interpersonal trauma exposure are particularly concerning, given available evidence that alcohol use problems, in turn, convey increased risk for revictimization (Messman-Moore & Long, 2003). Research evaluating risk and protective factors for alcohol use problems is needed in this high-risk population, for the purposes of informing etiological and clinical models of PTSD-AUD comorbidity

Social support demonstrates stress buffering effects on both physiological and psychological health (Cohen, 2004; Cohen & Hoberman, 1983; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Ditzen & Heinrichs, 2014; Umberson, Crosnoe, & Reczek, 2010) and decreases risk for PTSD and related psychopathology post-trauma exposure (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Gros et al., 2016;Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003;Schumm, Briggs-Phillips, & Hobfoll, 2006). In young adulthood, a time where many form their first significant romantic relationship, romantic relationships are an increasingly important source of social support (Arnett, 2004; Shulman & Connolly, 2013). Involvement in romantic relationships is associated with reductions in stress (Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017; Ozer et al., 2003; Williams & Umberson, 2004) and alcohol use and problems (Bachman, O’Malley, & Johnston, 1984; Fleming, White, & Catalano, 2010; Kendler, Lönn, Salvatore, Sundquist, & Sundquist, 2016; Leonard & Rothbard, 1999; Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007). This underscores the potentially important role of romantic relationships in qualifying the association between PTSD and AUD.

Importantly, relationships are not uniformly protective, and the salutary effects of relationships depend, in part, on their quality (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Marshal, 2003; Marshall & Kuijer, 2017; Umberson et al., 2010). Satisfying relationships are typically associated with higher levels of partner support, which can protect against stress by promoting positive coping skills and healthy behaviors (Uchino, 2006; Umberson & Montez, 2010). Notably, higher relationship satisfaction may also motivate changes in heavy drinking habits (Khaddouma et al., 2016), and reduce drinking urges in women (Owens et al., 2013). In contrast, low quality romantic relationships may increase one’s risk for alcohol problems (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Marshal, 2003; Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007). Individuals who are dissatisfied with their intimate partnerships exhibit up to four times increased risk of developing alcohol use problems (Epstein & McCrady, 1998; Leonard & Eiden, 2007; Whisman, Weinstock, & Tolejko, 2006). Likewise, dissatisfying relationships are less likely to provide stress-buffering effects (Marshal, 2003), which may in turn exacerbate the vulnerability to alcohol misuse associated with PTSD.

Although there is reason to believe that high quality romantic relationships may mitigate the alcohol-related risks associated with PTSD symptoms, no studies to our knowledge have examined this possibility. Available research on the role of romantic relationships in the context of PTSD, more broadly, has focused on the negative impact of potentially traumatic events and PTSD on romantic relationship processes (Lambert, Engh, Hasbun, & Holzer, 2012; Marshall & kuijer, 2017; Wagner, Monson, & Hart, 2016), or on how relationship status may impact PTSD and AUD treatment-outcomes (Sripada, Pfeiffer, Rauch, & Bohnert, 2015; Wagner et al., 2016). This research is almost exclusively conducted in male, Veteran samples with current diagnoses of PTSD and/or AUD (Brewin et al., 2000; Lambert et al., 2012). Research on the role of romantic relationship quality on associations between PTSD symptoms and risky drinking patterns from an etiological perspective, particularly in high-risk young-adult populations, would provide novel insights into theoretical and clinical models of PTSD and AUD.

The primary aim of the current study was to examine the main and interactive effects of PTSD symptoms and romantic relationship quality on patterns of alcohol consumption (i.e., past 30-day alcohol use quantity, frequency, and binge frequency) and alcohol-related consequences (i.e., alcohol-related consequences subscale [items 4–10] of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test [AUDIT]; Babor, de la Fuente, Saunders, & Grant, 1992) in college students with a history of interpersonal trauma (excluding intimate partner violence), above and beyond the covariates of sex (given established sex differences in PTSD (Breslau, Davis, Andreski, Peterson, & Schulz, 1997; Breslau et al., 1998; Kessler et al., 1995) and AUD risk (Grant, Stinson, Dawson, Chou, Dufour, Compton, & Kaplan, 2004; Kessler et al., 1994)), number of lifetime traumatic events (to ensure that associations between PTSD and alcohol use outcome are not better accounted for by trauma history), and relationship duration (to account for potential differences in findings as a function of relationship stage). We hypothesized that greater levels of PTSD symptoms would be associated with greater levels of alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences, and that greater romantic relationship quality would be associated with decreased alcohol use outcomes. We also hypothesized that romantic relationship quality would moderate the association between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol use outcomes, such that PTSD symptoms would be associated with worse alcohol use outcomes for those low, but not high, in romantic relationship quality.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and procedures

Participants were 101 undergraduate students (78.2% women; 53.8% 1st year students, 19.2% 2nd year students, 26.9% 3rd year students) participating in a university-wide study of environmental and genetic risk for various health behaviors conducted at a large, urban, public university in the Mid-Atlantic region (Dick et al., 2014). Individuals were recruited to complete additional assessments of trauma and alcohol constructs if they screened positive for probable trauma exposure and current alcohol use in the parent study assessment battery (see Berenz, Kevorkian et al., 2016 for additional detail). Participants were selected for current study analyses if they reported being in a current monogamous relationship (i.e., an exclusive relationship of three months or longer), endorsed a history of sexual or physical assault (excluding intimate partner violence), and reported past 30-day alcohol use at the parent study timepoint closest to the trauma and alcohol assessment.

The parent study represents a college-wide effort to evaluate college students’ health throughout their undergraduate careers. The study relies on web-based assessments of health behaviors, beginning during freshman fall semester, and continuing every spring semester until attrition or graduation. Detailed study procedures are published elsewhere (Dick et al., 2014). Upon enrolling in the parent study, participants may be contacted based on their initial responses to complete further assessments for secondary studies. The current project utilizes secondary, cross-sectional survey data collected on the first three cohorts of the parent study. Detailed secondary study procedures are previously published (Berenz, Kevorkian et al., 2016). All survey data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Harris et al., 2009), a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. The university Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

2.2. Measures

The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany et al., 2000) is a 23-item self-report questionnaire assessing the occurrence of a range of potentially traumatic events (PTEs; e.g., natural disaster, assault). The TLEQ records detailed information about lifetime PTE history, including types and frequencies of trauma, as well as the participants’ subjective assessment of which trauma type was the “most bothersome.” The TLEQ was administered in the secondary study. Prior studies have established good psychometric properties of the TLEQ (Kubany et al., 2000).

Past 30-day PTSD symptoms were screened in the secondary study using the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013) based on the participants’ events they identified in the TLEQ as being the “most bothersome.” The PCL-5, which is based on DSM-5 PTSD criteria (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), asks that participants rate item severity from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The total score of the PCL-5 was used as a measure PTSD symptom severity, and a cut-off score of 33 indicated a positive PTSD screen (Bovin et al., 2016). Prior research supports the use of the PCL-5 in college populations (Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, 2015). This measure showed high internal consistency (α = 88).

Relationship quality was assessed in the primary study with three questions from the Hendrick Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Hendrick, 1988), including: general relationship satisfaction, how well the partner meets one’s needs, and how good the relationship is compared to most. Individuals rated their responses on a sliding scale that ranged from 0 (Not at all) to 100 (A Lot/Very Much). Responses were averaged and transformed to range from 1 to 7 to be consistent with the original scale (M = 6.21; SD = 0.83). RAS scores from the primary study timepoint closest to the trauma and alcohol assessment were used in study analyses. This measure showed high internal consistency (α = 93).

Past 30-day alcohol use was assessed in the secondary study using multiple items adapted from the Timeline Follow Back Assessment (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992). These items measured alcohol use quantity (“On the days that you drank during the past 30 days, how many drinks did you usually have each day?”), frequency (“During the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink one or more drinks of an alcoholic beverage?”), and binge frequency (“In the past 30 days, on how many days did you have 5 or more drinks (for men)/4 or more drinks (for women) in a single sitting (considered about a 2 h period)?”).

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al., 1992) is a widely used screening tool for assessing alcohol use problems. Psychometric research on the AUDIT supports a cut-off score of 8, such that > = 8 classifies individuals as having “moderate” or greater alcohol use problems, with higher scores being consistent with greater problem severity (Babor et al., 1992). The AUDIT was administered in the secondary study, and the current study utilized total scores on the alcohol-related consequences subscale of the AUDIT (i.e., alcohol dependence and harmful alcohol use; items 4–10) to measure past-year alcohol-related consequences (Doyle, Donovan, & Kivlahan, 2007). This subscale showed good internal consistency (α = 0.70).

2.3. Data analytic plan

Analyses were conducted using IBM-SPSS 24. Four hierarchical linear regressions were run to test the study hypotheses with respect to alcohol use quantity, alcohol use frequency, alcohol binge frequency, and alcohol-related consequences. Step one: sex (1 = male, 2 = female), cumulative trauma load (TLEQ), and relationship duration. Step two: PCL-5 total score and Relationship Quality. Step three: PCL-5 total score × Relationship Quality. Significant interactions were graphed to evaluate the nature of effects (Cohen & Cohen, 1983), and simple slope analyses were conducted to evaluate significant interactions statistically (i.e., evaluating whether the slope is significantly different from 0 at each level of the moderator; Holmbeck, 2002).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics and zero-order (bivariate) correlations

Evaluation of descriptive statistics (Table 1) indicates substantial diversity of the sample with respect to demographic characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity, sex, PTE endorsement) and endorsement of PTSD symptoms and alcohol use problems. Participants endorsed relatively new relationships and high relationship satisfaction. Square root or reflected square root transformations were applied to correct for positive and negative skewness as indicated, resulting in normally distributed variables for alcohol use frequency (Skew = 0.73, Kurt = −0.09), alcohol use quantity (Skew = 0.62, Kurt = 0.61), binge drinking frequency (Skew = 0.58, Kurt = −0.36), alcohol-related consequences (Skew = 0.56 Kurt = 0.15), and relationship quality (Skew = 1.08, Kurt = 0.68). No transformations were applied to the PCL-5 total score variable (Skew = 0.73, Kurt = −0.23).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

| Variable | Mean (SD) or % | Observed range |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (% Women) | 78.2% | |

| Year in School | ||

| First Year | 53.8% | |

| Second Year | 19.2% | |

| Third Year | 26.9% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 5.9% | |

| Black/African American | 10.8% | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4.9% | |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 1.0% | |

| Biracial | 5.9% | |

| White | 70.6% | |

| Chose not to answer | 1.0% | |

| Interpersonal PTEs (% endorsed) | ||

| Armed robbery | 8.8% | |

| Physical assault by stranger | 4.0% | |

| Witnessed physical assault by stranger | 11.8% | |

| Threatened death or serious injury | 33.3% | |

| Physical abuse growing up | 16.2% | |

| Witnessed family violence growing up | 28.7% | |

| Childhood sexual assault before age 13 | 24.5% | |

| Childhood sexual assault ages 13–17 | 17.0% | |

| Sexual assault as adult (18 or older) | 15.7% | |

| Accidental PTEs (% endorsed) | ||

| Natural disaster | 66.7% | |

| Motor vehicle accident | 14.7% | |

| Other accident | 13.0% | |

| Unexpected death of loved one | 69.6% | |

| Loved one survived life-threating illness/accident | 56.6% | |

| Life-threatening illness (self) | 13.7% | |

| Number of lifetime PTE types | 5.26 (2.41) | 1–12 |

| PCL-5 total score | 22.02 (17.52) | 0–69 |

| Positive PTSD screen | 24.0% | |

| Average relationship quality | 6.21(0.83) | 2.86–7 |

| Average relationship duration (months) | 10.80(3.33) | |

| Alcohol use quantity (past 30 days) | 3.71 (2.64) | 1–17 |

| Alcohol use frequency (past 30 days) | 6.38 (5.63) | 1–28 |

| Alcohol binge frequency (past 30 days) | 2.88 (4.14) | 0–22 |

| Alcohol-related consequences (past year) | 2.96 (3.91) | 0–22 |

| Positive Screen for Moderate Alcohol Problems | 45.1% |

Note. PTE = potentially traumatic event (assessed via Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire; Kubany et al., 2000); PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Weathers et al., 2013); Positive PTSD Screen = PCL-5 > 33; Alcohol-related consequences = Items 4–10 of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Babor et al., 1992); Positive Screen for Moderate Alcohol Problems = AUDIT total score > 8.

Correlations were run for key study variables (Table 2). Men endorsed greater alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences, while women endorsed greater PTSD symptom severity. Greater cumulative trauma was associated with greater PTSD symptoms and greater alcohol use frequency, and greater PTSD symptoms were associated with greater alcohol use frequency, binge frequency, and alcohol-related consequences. Relationship duration was inversely associated with alcohol use quantity, binge frequency, and alcohol-related consequences, and relationship quality was inversely associated with alcohol-related consequences. All alcohol variables were significantly inter-related.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex (1 = male, 2 = female) | – | |||||||

| 2. # of lifetime PTE types | 0.05 | – | ||||||

| 3. Relationship duration | −0.02 | −0.01 | – | |||||

| 4. PCL-5 total score | 0.11* | 0.34** | −0.12 | – | ||||

| 5. Relationship quality | −0.02 | −0.63 | 0.15 | −0.12 | – | |||

| 6. Alcohol use frequency | −0.18** | 0.16** | −0.06 | 0.21** | −0.02 | – | ||

| 7. Alcohol use quantity | −0.23** | 0.05 | −0.17* | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.24** | – | |

| 8. Alcohol binge frequency | −0.19** | 0.10 | −0.19* | 0.23** | −0.05 | 0.75** | 0.51** | – |

| 9. Alcohol consequences | −0.13* | 0.10 | −0.32** | 0.40** | −0.21* | 0.50** | 0.36** | 0.57** |

Note. PTE = potentially traumatic event (assessed via Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire; Kubany et al., 2000); PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Weathers et al., 2013); Alcohol consequences = alcohol-related consequences subscale (i.e., items 4–10) of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Babor et al., 1992). Square root transformations were applied to correct for positive skewness for alcohol use frequency, alcohol use quantity, binge drinking frequency and alcohol-related consequences variables. Reflected square root transformations were applied to correct for negative skewness of the relationship quality variable.

p < .05.

p < .01.

3.2. PTSD symptoms, relationship quality, and alcohol use quantity

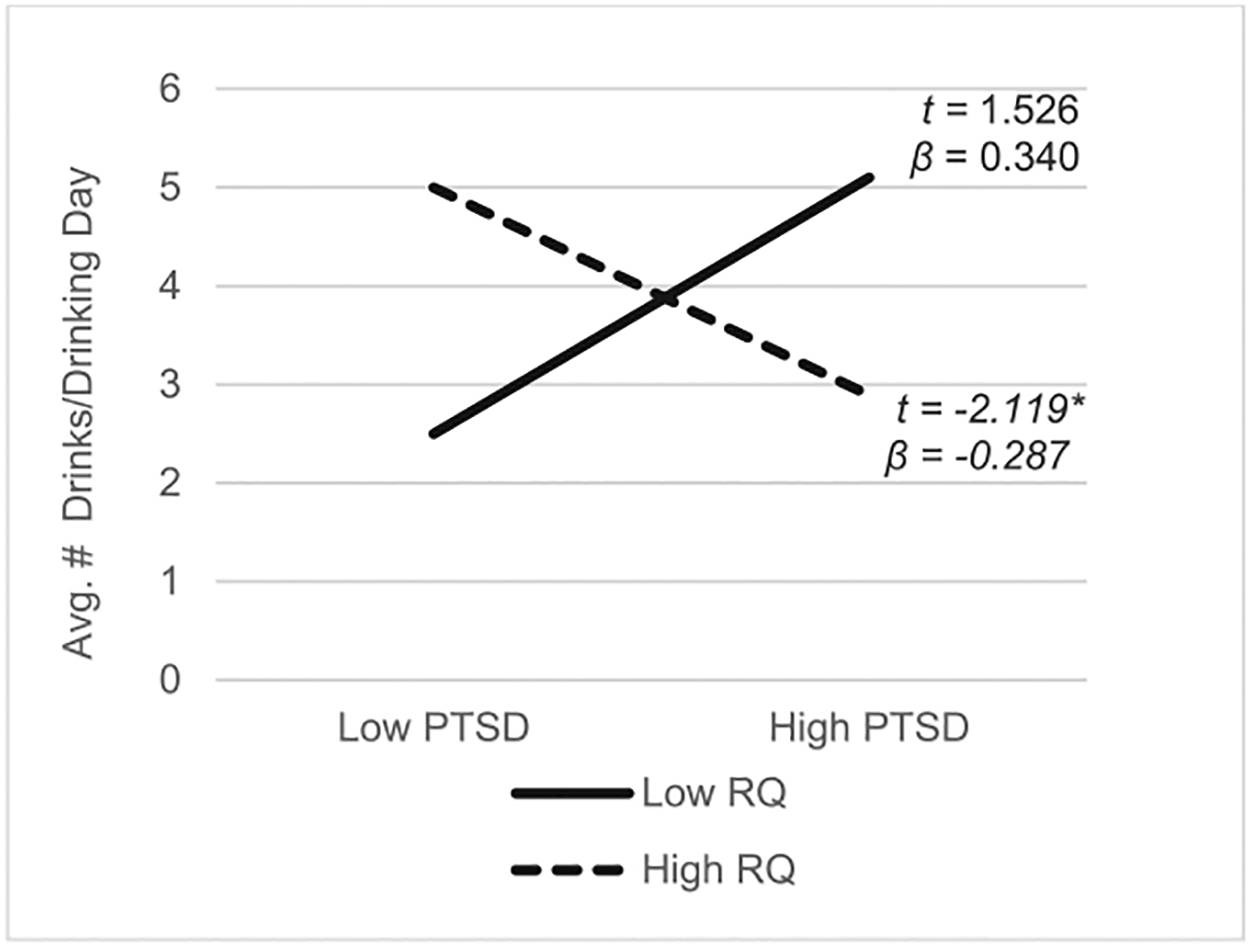

See Table 3. The model accounted for a significant 21.4% of variance in alcohol use quantity (F(6,101) = 4.30, p = .001). Step one of the model accounted for 14.0% of variance, with men and individuals in shorter relationships reporting greater average drinks per episode. The main effects of PTSD symptom severity and relationship quality (step two) were not significantly associated with alcohol use quantity above and beyond the covariates. The interaction term at step three of the model was significantly associated with alcohol use quantity, accounting for an additional 5.0% of variance. The visual form of the interaction was supported by simple slope analyses (Fig. 1). For participants in high quality relationships, higher PTSD symptom severity was associated with reduced alcohol use quantity (t = −2.119, β = −0.287, p = .038). In contrast, for participants in low quality relationships, alcohol use quantity did not vary as a function of PTSD symptom severity (t = 1.526, β = 0.340, p = .133).

Table 3.

Associations Among Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Symptoms, Relationship Quality, and Alcohol Use and Problems.

| ΔR2 | t | β | sr2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion variable: Alcohol use quantity | |||||

| Step 1 | 0.140 | 0.002 | |||

| Sex | −3.229 | −0.304 | 0.092 | 0.002 | |

| Number of Lifetime PTEs | 0.403 | 0.038 | 0.001 | 0.688 | |

| Relationship duration | −2.318 | −0.217 | 0.047 | 0.023 | |

| Step 2 | 0.024 | 0.252 | |||

| PCL-5 | −1.515 | −0.154 | 0.020 | 0.133 | |

| Relationship quality | 0.482 | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.631 | |

| Step 3 | 0.050 | 0.016 | |||

| Interaction term | −2.448 | −0.972 | 0.050 | 0.016 | |

| Criterion variable: Alcohol use frequency | |||||

| Step 1 | 0.109 | 0.010 | |||

| Sex | −3.235 | −0.309 | 0.095 | 0.002 | |

| Number of Lifetime PTEs | 0.825 | 0.079 | 0.006 | 0.411 | |

| Relationship duration | −0.686 | −0.065 | 0.004 | 0.494 | |

| Step 2 | 0.003 | 0.850 | |||

| PCL-5 | 0.497 | 0.052 | 0.002 | 0.621 | |

| Relationship quality | −0.204 | −0.021 | 0.000 | 0.839 | |

| Step 3 | 0.020 | 0.147 | |||

| Interaction term | −1.462 | −0.610 | 0.020 | 0.147 | |

| Criterion variable: Alcohol binge frequency | |||||

| Step 1 | 0.148 | 0.001 | |||

| Sex | −3.396 | −0.319 | 0.101 | 0.001 | |

| Number of Lifetime PTEs | 0.257 | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.798 | |

| Relationship duration | −2.342 | −0.220 | 0.048 | 0.021 | |

| Step 2 | 0.000 | 0.998 | |||

| PCL-5 | 0.069 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.945 | |

| Relationship quality | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.989 | |

| Step 3 | 0.031 | 0.063 | |||

| Interaction term | −1.878 | −0.762 | 0.031 | 0.063 | |

| Criterion variable: Alcohol-related consequences | |||||

| Step 1 | 0.218 | 0.000 | |||

| Sex | −2.647 | −0.238 | 0.060 | 0.009 | |

| Number of Lifetime PTEs | 1.762 | 0.159 | 0.025 | 0.081 | |

| Relationship duration | −3.975 | −0.357 | 0.127 | < 0.001 | |

| Step 2 | 0.079 | 0.006 | |||

| PCL-5 | 2.810 | 0.262 | 0.059 | 0.006 | |

| Relationship quality | −1.260 | −0.113 | 0.012 | 0.211 | |

| Step 3 | 0.050 | 0.009 | |||

| Interaction term | −2.688 | −0.973 | 0.050 | 0.009 | |

Note. PTE = potentially traumatic event (assessed via Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire; Kubany et al., 2000); PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Weathers et al., 2013); Alcohol-related consequences = alcohol-related consequences subscale (i.e., items 4–10) of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Babor et al., 1992).

Fig. 1.

Association between PTSD Symptoms and Alcohol Use Quantity at Low and High Levels of Romantic Relationship Quality. Note. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and alcohol use quantity at low and high levels of romantic relationship quality. “Low” = [1/2] SD below sample mean; “High” = [1/2] SD above sample mean; Alcohol use quantity = past 30 days; PTSD = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013); RQ = relationship quality, measured with the Hendrick Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Hendrick, 1988). *p < .05.

Note. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and alcohol use quantity at low and high levels of romantic relationship quality. “Low” = [1/2] SD below sample mean; “High” = [1/2] SD above sample mean; Alcohol use quantity = past 30 days; PTSD = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013); RQ = relationship quality, measured with the Hendrick Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Hendrick, 1988). * p < .05

3.3. PTSD symptoms, relationship quality, and alcohol use frequency

The model accounted for a significant 13.2% of variance in alcohol use frequency (F(6,101) = 2.41, p = .030). The covariates at step one of the model accounted for 10.9% of variance, with male sex being associated with more frequent alcohol use. Neither the main effects of PTSD symptom severity and relationship quality at step two of the model nor the interaction term at step three of the model were significantly associated with alcohol use frequency.

3.4. PTSD symptoms, relationship quality, and binge drinking frequency

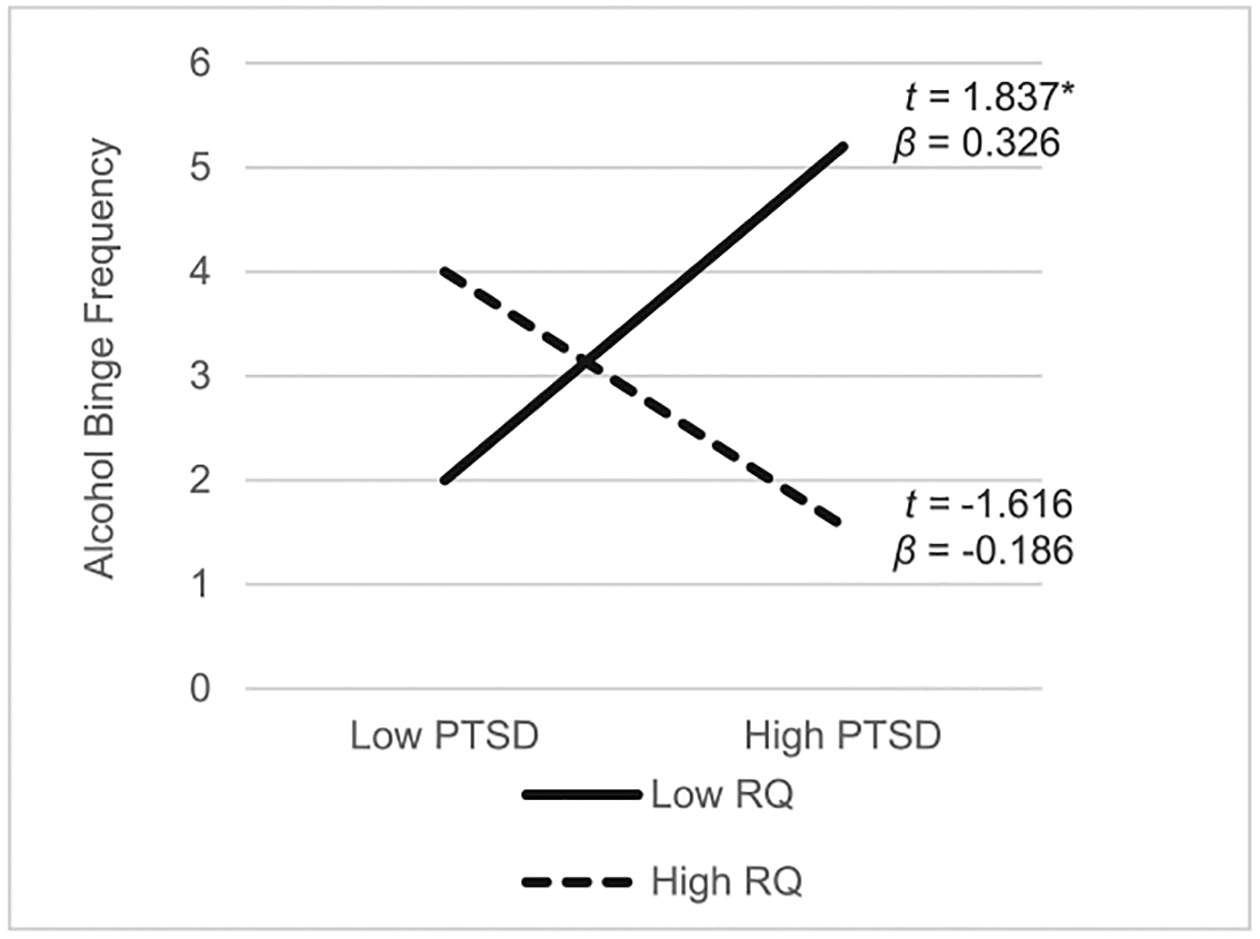

The model accounted for a significant 17.9% of variance in binge drinking frequency (F(6,100) = 3.41, p = .004). Step one of the model accounted for 14.8% of variance, with men and individuals in shorter relationships reporting more binge drinking episodes. Although the main effects of PTSD symptom severity and relationship quality were not significantly associated with binge drinking frequency, the interaction of PTSD and relationship quality was nominally significant, accounting for a unique 3.1% of variance (see Fig. 2). For participants in low quality relationships, the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and binge drinking frequency trended towards statistical significance (t = 1.837, β = 0.326, p = .070), with greater PTSD symptom severity being associated with higher binge drinking frequency. Conversely, for participants in high quality relationships, binge drinking frequency did not vary as a function of PTSD symptom severity (t = −1.616, β = −0.186, p = .110).

Fig. 2.

Association between PTSD Symptoms and Alcohol Binge Frequency at Low and High Levels of Romantic Relationship Quality. Note. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and binge drinking frequency at low and high levels of romantic relationship quality. “Low” = [1/2] SD below sample mean; “High” = [1/2] SD above sample mean; Alcohol binge frequency = past 30 days; PTSD = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013); RQ = relationship quality, measured with the Hendrick Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Hendrick, 1988). * p < .10.

Note. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and binge drinking frequency at low and high levels of romantic relationship quality. “Low” = [1/2] SD below sample mean; “High” = [1/2] SD above sample mean; Alcohol binge frequency = past 30 days; PTSD = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013); RQ = relationship quality, measured with the Hendrick Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Hendrick, 1988). *p< .10

3.5. PTSD symptoms, relationship quality, and alcohol-related consequences

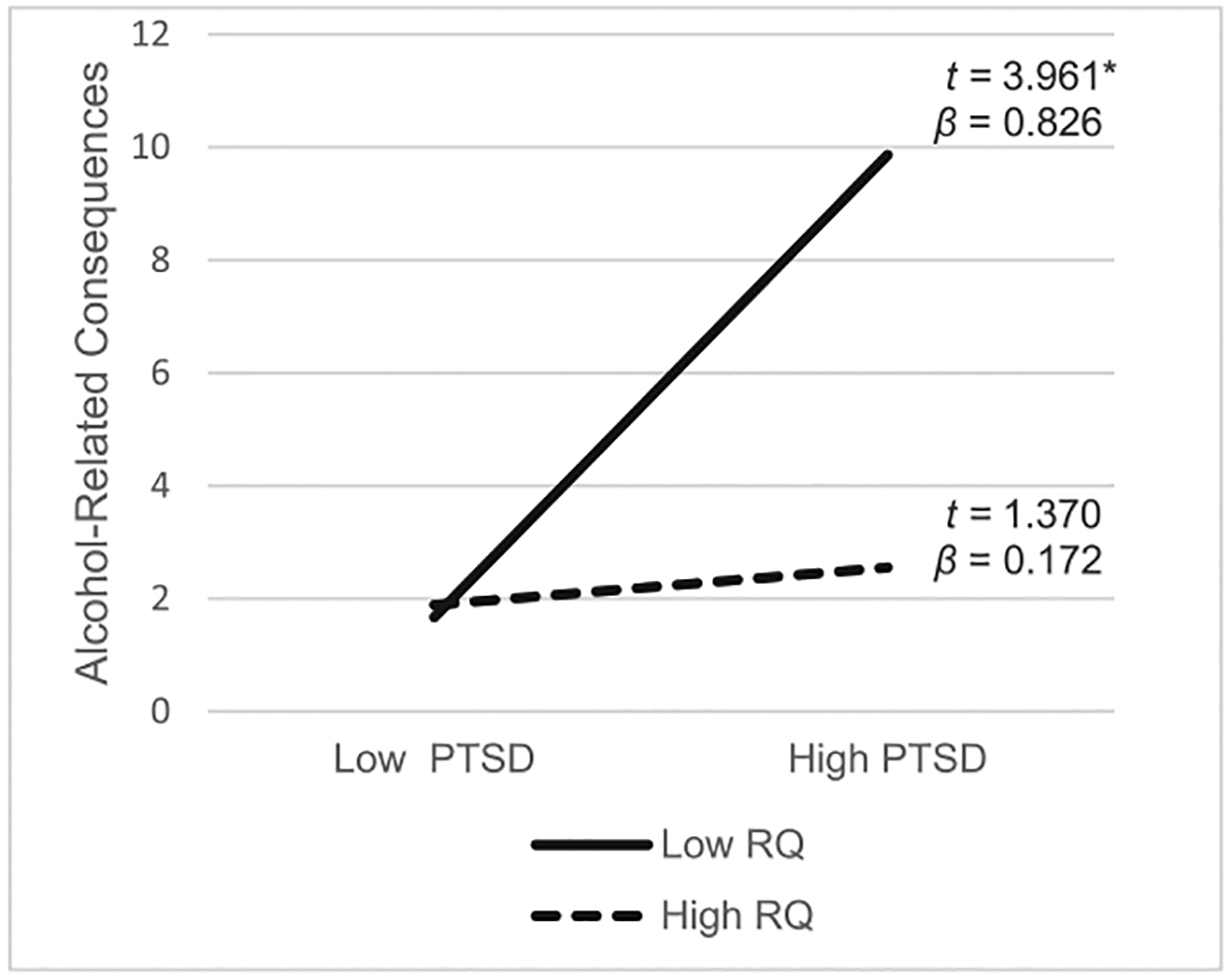

The model accounted for a significant 34.7% of variance in AUDIT alcohol-related consequences total score (F(6,100) = 7.06, p < .001). The covariates at step one of the model accounted for a significant 21.8% of variance, with men and individuals in shorter relationships reporter greater alcohol-related consequences. Step 2 of the model accounted for a unique 7.9% of variance, with the main effect of PTSD symptom severity, but not relationship quality, being significantly positively associated with alcohol-related consequences. The interaction of PTSD and relationship quality at Step 3 was also significant, accounting for an additional 5.0% of variance. Greater PTSD symptom severity was associated with greater alcohol-related consequences for those reporting low, but not high, relationship quality, and simple slope analyses supported the visual form of this interaction (see Fig. 3). For participants in low quality relationships, higher PTSD symptom severity was associated with more alcohol-related consequences (t = 3.961, β = 0.826, p < .001). For participants in high quality relationships, alcohol-related consequences did not vary as a function of PTSD symptom severity (t = 1.370, β = 0.172, p = .176).

Fig. 3.

Association between PTSD Symptoms and Alcohol-Related Consequences at Low and High Levels of Romantic Relationship Quality. Note. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and alcohol-related consequences at low and high levels of romantic relationship quality. “Low” = [1/2] SD below sample mean; “High” = [1/2] SD above sample mean; Alcohol-related consequences = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) alcohol-related consequences subscale (i.e., items 4–10; Babor et al., 1992); PTSD = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013); RQ = relationship quality, measured with the Hendrick Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Hendrick, 1988). * p < .05.

Note. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and alcohol-related consequences at low and high levels of romantic relationship quality. “Low” = [1/2] SD below sample mean; “High” = [1/2] SD above sample mean; Alcohol-related consequences = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) alcohol-related consequences subscale (i.e., items 4–10; Babor, de la Fuente, Saunders, & Grant, 1992); PTSD = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013); RQ = relationship quality, measured with the Hendrick Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Hendrick, 1988). * p < .05

4. Discussion

The current study examined the main and interactive effects of PTSD symptoms and romantic relationship quality on patterns of alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences in college students with interpersonal trauma exposure. We found distinct patterns of effects across different dimensions of alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences, which we interpret in turn. First, there existed a significant main effect of PTSD symptom severity on alcohol-related consequences, such that greater PTSD symptom severity was associated with greater alcohol-related consequences. This finding is consistent with prior research in college samples (Read, Wardell, & Colder, 2013; Tripp, McDevitt-Murphy, Avery, & Bracken, 2015).

Additionally, romantic relationship quality moderated the association between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol use quantity, but not alcohol use frequency. This suggests that romantic relationship quality primarily modifies the association between PTSD symptomatology and how much one drinks, rather than how often. As expected, those with more severe PTSD symptoms who were in high quality relationships used less alcohol compared to those who were in low quality relationships. These findings are consistent with previous literature suggesting that satisfying, high quality romantic relationships can buffer against the deleterious effects of stress (Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017; Ozer et al., 2003; Williams & Umberson, 2004), promote positive coping skills, and encourage engagement in healthier behaviors (Uchino, 2006; Umberson & Montez, 2010; Khaddouma et al., 2016). Unexpectedly, we found that for those in low quality relationships, alcohol use quantity did not vary as a function of PTSD symptom severity. Although we are cautious about interpreting a null effect, it may be that the social nature of college provides increased opportunity for social support relative to other non-college drinking contexts, thereby buffering individuals from the impact of a lower quality relationship on the PTSD-alcohol use association. Future research examining the potential influence of PTSD symptoms and relationship quality on drinking motives may clarify the nature of the association.

Romantic relationship quality also moderated the association between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol-related consequences. For those in low quality relationships, greater PTSD symptom severity was associated with more alcohol-related consequences. In contrast, there was no relationship between PTSD symptoms and alcohol-related consequences for those in high quality relationships. These findings complement our alcohol use quantity findings to demonstrate that high quality relationships have stress-buffering effects (Marshal, 2003). The pattern of findings with respect to binge frequency complemented that for alcohol-related consequences; however, the interaction only trended towards statistical significance. Replication of the current study would be useful for clarifying the role of romantic relationship quality in the association between PTSD symptoms and binge drinking behavior.

The current study findings have important theoretical and clinical implications. There is a robust literature demonstrating that high social support reduces risk for PTSD symptoms following trauma exposure (Brewin et al., 2000; Coker et al., 2002; Haden, Scarpa, Jones, & Ollendick, 2007; Vranceanu, Hobfoll, & Johnson, 2007). However, the current results are novel in that they suggest potential for a high-quality romantic relationship to buffer individuals suffering from PTSD symptoms against problematic alcohol consumption, even for young adults in relatively new relationships. If relationship quality plays a causal role in PTSD-alcohol associations, then a romantic partner may have the potential to serve as a buffer for young adults at risk for alcohol problems, similar to the utility of a supportive, prosocial marriage partner in reducing desistance in adult populations (Craig & Foster, 2013; Kendler et al., 2016; Lee, Chassin, & MacKinnon, 2015). Longitudinal and human laboratory studies would have a better ability to clarify whether causal explanations fit the observed findings. If causal explanations do indeed fit these findings, college counseling centers may benefit from assessing whether students’ romantic partners are potential barriers or sources of support in the context of alcohol use problems. Individuals in low quality relationships may also benefit from learning ways to improve their romantic relationships, which may reduce symptoms and problematic alcohol use.

The present results should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. First, the present study utilizes a self-selecting college sample, which may not be representative of all young adults. Second, we focused on an individual’s self-report of their relationship, alcohol use, and PTSD symptoms. Future studies should include partner reports of similar constructs, especially relationship quality. Third, to avoid a potential confound in study analyses, we excluded participants endorsing intimate partner violence in the context of traumatic event exposure. Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of measures to characterize violence within relationships to meaningfully study similarities and differences in the associations studied under conditions of intimate partner violence. Similarly, there are a number of potential additional factors that could influence the observed associations and which are largely understudied in this field, such as family history of AUD, other sources of social support, and other factors related to differences across college environments (e.g., school size, rates of participation in Greek life, etc.). Future studies could benefit from further study of these domains. Fourth, our study also cannot determine causation or temporal associations among key variables due to the cross-sectional approach. Future studies would benefit from assessing the timing of these constructs using a longitudinal design. Finally, given the relatively small sample size for evaluating interaction effects, it is possible that the observed significant interactions are a result of Type I error. Replication of these results is needed.

Social support quality during times of distress can significantly help or hinder individuals’ ability to manage symptoms and setbacks. During young adulthood, romantic relationships gain in importance for well-being (Arnett, 2000; Schulenberg, Bryant, & O’Malley, 2004; Seiffge-Krenke, 2003); a high-quality romantic relationship may protect trauma-exposed young adults from developing additional clinical complications, such as alcohol use problems.

HIGHLIGHTS.

PTSD interacts with relationship quality to influence alcohol use outcomes.

Greater PTSD and worse relationship quality is associated with elevated consumption.

Greater PTSD and worse relationship quality is associated with greater consequences.

PTSD and relationship quality did not interact to influence alcohol use frequency.

Acknowledgements

Spit for Science has been supported by Virginia Commonwealth University, P20 AA017828, R37AA011408, K02AA018755, and P50 AA022537 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and UL1RR031990 from the National Center for Research Resources and National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research. This study also was supported by a NIAAA grant awarded to Dr. Berenz (1K99AA022385). We would like to thank the Spit for Science participants for making this study a success, as well as the many University faculty, students, and staff who contributed to the design and implementation of the project.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106216.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2004). Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, & Grant M (1992). AUDIT: The alcohol use disorders identification test Guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, & Johnston LD (1984). Drug use among young adults: The impacts of role status and social environment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(3), 629–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenz EC, Cho SB, Overstreet C, Kendler K, Amstadter AB, & Dick DM (2016). Longitudinal investigation of interpersonal trauma exposure and alcohol use trajectories. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenz EC, Kevorkian S, Chowdhury N, Dick DM, Kendler KS, & Amstadter AB (2016). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, anxiety sensitivity, and alcohol use motives in college students with a history of interpersonal trauma. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors : Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 30(7), 755–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, & Domino JL (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin M, Marx B, Weather FW, Gallagher M, Rodriguez P, Schnurr P, & Keane TM (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson EL, & Schultz LR (1997). Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54(11), 1044–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, & Andreski P (1998). Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit area survey of trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55(7), 626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, & Valentine JD (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 748–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, & Jacobson KC (2012). Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(2), 154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, & Cohen P (1983). Applied Multiple regression/correlation analysis for behavioral sciences. NJ Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Hoberman HM (1983). Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13(2), 99–125. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59(8), 676–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, & Davis KE (2002). Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-based Medicine, 11(5), 465–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig J, & Foster H (2013). Desistance in the transition to adulthood: The roles of marriage, military, and gender. Deviant Behavior, 34(3), 208–223. [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Nasim A, Edwards AC, Salvatore JE, Cho SB, Adkins A, … Kendler KS (2014). Spit for Science: Launching a longitudinal study of genetic and environmental influences on substance use and emotional health at a large US university. Frontiers in Genetics, 5(47), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzen B, & Heinrichs M (2014). Psychobiology of social support: The social dimension of stress buffering. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 32(1), 149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle SR, Donovan DM, & Kivlahan DR (2007). The factor structure of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(3), 474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EE, & McCrady BS (1998). Behavioral couples treatment of alcohol and drug use disorders: Current status and innovations. Clinical Psychology Review, 18(6), 689–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, & Catalano RF (2010). Romantic relationships and substance use in early adulthood: An examination of the influences of relationship type, partner substance use, and relationship quality. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(2), 153–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Patricia Chou S, Jung J, Zhang H, … Hasin DS (2015). Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 72(8), 757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, … Kaplan K (2004, August). Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, Flanagan JC, Korte KJ, Mills AC, Brady KT, & Back SE (2016). Relations between social support, PTSD symptoms, and substance use in veterans. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(7), 764–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haden SC, Scarpa A, Jones RT, & Ollendick TH (2007). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and injury: The moderating role of perceived social support and coping for young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(7), 1187–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick SS (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family, 50, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, & Winter MR (2006). Age of alcohol-dependence onset: Associations with severity of dependence and seeking treatment. Pediatrics, 118, E755–E763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN (2002). Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Special Issue on Methodology and Design, 27(1), 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, & Sartor CE (2016). The natural course of substance use and dependence In Sher KJ (Author), The Oxford handbook of substance use and substance use disorders (Vol. 1, pp. 67–131). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE & Miech RA (2014). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2013: Volume 2, College students and adults ages 19–55. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BRK, & Bradbury TN (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 3–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Lönn SL, Salvatore J, Sundquist J, & Sundquist K (2016). Effect of marriage on risk for onset of Alcohol Use Disorder: A longitudinal and co-relative analysis in a Swedish national sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(9), 911–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005, June). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, … Kendler KS (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51(1), 8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, & Nelson CB (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(12), 1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, & Wilson SJ (2017). Lovesick: How couples’ relationships influence health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13(1), 421–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaddouma A, Shorey RC, Brasfield H, Febres J, Zapor H, Elmquist J, & Stuart GL (2016). Drinking and dating: Examining the link among relationship satisfaction, hazardous drinking, and readiness-to-change in college dating relationships. Journal of College Student Development, 57(1), 32–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Haynes SN, Leisen MB, Owens JA, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, & Burns K (2000). Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 12(2), 210–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JE, Engh R, Hasbun A, & Holzer J (2012). Impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on the relationship quality and psychological distress of intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(5), 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MR, Chassin L, & MacKinnon DP (2015). Role transitions and young adult maturing out of heavy drinking: Evidence for larger effects of marriage among more severe premarriage problem drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(6), 1064–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, & Eiden RD (2007). Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3(1), 285–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, & Rothbard JC (1999). Alcohol and the marriage effect. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, s13, 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Hewitt BG, & Grant BF (2004). Alcohol use disorders and mood disorders: A National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 56(10), 718–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Coley RL, Lombardi CM, Lynch AD, Markowitz AJ, & Jaffee SR (2013). Changes in health risk behaviors for males and females from early adolescence through early adulthood. Health Psychology, 32(6), 685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP (2003). For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(7), 959–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall EM, & Kuijer RG (2017). Weathering the storm? The impact of trauma on romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, & Long PJ (2003). The role of childhood sexual abuse sequelae in the sexual revictimization of women: An empirical review and theoretical reformulation. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(4), 537–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, & Johnston LD (2002). Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, (S14), 23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare T, & Sherrer M (2011). Drinking motives as mediators between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol consumption in persons with severe mental illnesses. Addictive Behaviors, 36(5), 465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet C, Berenz EC, Kendler KS, Dick DM, & Amstadter AB (2017). Predictors and mental health outcomes of potentially traumatic event exposure. Psychiatry Research, 247, 296–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MD, Hallgren KA, Ladd BO, Rynes K, McCrady BS, & Epstein E (2013). Associations between relationship satisfaction and drinking urges for women in alcohol behavioral couples and individual therapy. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 31, 415–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, & Weiss DS (2003). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 52–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wardell JD, & Colder CR (2013). Reciprocal associations between PTSD symptoms and alcohol involvement in college: A three-year trait-state-error analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(4), 984–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C, Mohr CD, Del Boca FK, Mattson ME, Young L, Brady K, & Nickless C (2001). Self-reports of physical, sexual and emotional abuse in an alcoholism treatment sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62(1), 114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhule-Louie DM, & McMahon RJ (2007). Problem behavior and romantic relationships: Assortative mating, behavior contagion, and desistance. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 10(1), 53–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Bryant AL, & O’Malley PM (2004). Taking hold of some kind of life: How developmental tasks relate to trajectories of well-being during the transition to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 1119–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, Briggs-Phillips M, & Hobfoll SE (2006). Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among inner-city women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(6), 825–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I (2003). Testing theories of romantic development from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence of a developmental sequence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27(6), 519–531. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S, & Connolly J (2013). The challenge of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Hunt-Carter EE, Nabors-Oberg RE, Sher KJ, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, … Heath AC (2004). Do college students drink more than their non-college-attending peers? Evidence from a population-based longitudinal female twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(4), 530–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS (2005). Alcohol use disorders among US college students and their non-college-attending peers. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB (1992). Timeline Followback: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption In Allen J, & Litten RZ (Eds.). Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychological and biological methods (pp. 41–72). Totowa, NJ: Humans Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sripada RK, Pfeiffer PN, Rauch SAM, & Bohnert K (2015). Social support and mental health service use among individuals with PTSD in a nationally-representative survey. Psychiatric Services, 66(1), 65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp JC, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Avery ML, & Bracken KL (2015). PTSD symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and alcohol-related consequences among college students with a trauma history. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 11(2), 107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Crosnoe R, & Reczek C (2010). Social relationships and health behavior across life course. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 139–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, & Montez JK (2010). Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(Suppl), S54–S66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli J, Balaraman G, Hahn J, Wallace H, & Bux D (1999). The role of uncontrollable trauma in the development of PTSD and alcohol addiction. Alcohol Research & Health: The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 23(4), 256–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranceanu AM, Hobfoll SE, & Johnson RJ (2007). Child multi-type maltreatment and associated depression and PTSD symptoms: The role of social support and stress. Child abuse & neglect, 31(1), 71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AC, Monson CM, & Hart TL (2016). Understanding social factors in the context of trauma: Implications for measurement and intervention. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 25(8), 831–853. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop AE, Back SE, Verduin ML, & Brady KT (2007). Triggers for cocaine and alcohol use in the presence and absence of posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 32(3), 634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, & Schnurr PP (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) Scale available from the National. Center for PTSD. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Weinstock LM, & Tolejko N (2006). Marriage and depression In Keyes CLM, & Goodman SH (Eds.). Women and depression: A handbook for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences (pp. 219–240). Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, & Umberson D (2004). Marital status, marital transitions, and health: A gendered life course perspective. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 45(1), 81–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]