Abstract

Viral respiratory infections (VRIs) are frequent after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and constitute a potential cause of mortality. We analyzed the incidence, risk factors, and prognosis of VRIs in a cohort of transplanted patients. More frequent viruses were human coronavirus and human rhinovirus followed by flu-like viruses and adenovirus. Risk factors for death were lymphocytopenia and high steroid dosage.

Key Words: Respiratory viral infections, Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Introduction

Common viral respiratory infections (VRIs) are an important cause of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HSCT) [1]. VRIs include respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza virus, parainfluenza virus (PIV), human adenovirus (AdV), human rhinovirus (HRV), and, more recently, metapneumovirus (MPV) and coronavirus (HCoV), which are prospectively and routinely sought in our center. Incidences range from 1% to 30% depending on the type of virus, detection method, and time from transplantation 1, 2, 3. In the present single-center study, we report on the incidence, clinical features, and outcome of VRIs during a 4-year period in transplanted patients.

Methods

Patients who underwent a first allogeneic HSCT in our center from December 2006 to August 2010 and were regularly followed in our center were eligible to be included in this study. Clinical and biological data were extracted from our local database completed by chart review. During the study period (December 2006 to June 2011), patients with respiratory symptoms possibly related to a respiratory virus had nasopharyngeal aspirates for PCR multiplex viral analysis [4] designed to detect RSV types A and B; AdV; HRV; human MPV; HCoV 229E, OC43, and NL63; PIV-1 to -4; influenza virus types A and B; and 4 different bacteria (Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Bordetella pertussis). Bacterial and fungal infections were documented by usual methods including bronchoalveolar lavage in patients with a suspicion of pneumonia.

Viruses were divided into 3 groups. HRV and HCoV share a more benign symptomatology of the common cold and low direct mortality rates and were thus compiled in one group [5]. Given their worse and on occasion fatal outcomes in the post-transplant setting, RSV, MPV, PIV, and influenza virus infections were gathered into a second flu-like group 1, 6, 7. AdV was allocated to a separate third group because it can disseminate [8].

Patients were analyzed based on their first episode of VRI according to the virus species or group. Death was considered as a competing event for VRI. Cumulative incidence of VRI was estimated using usual methodology for the first VRI of any virus and then for the first VRI by each of the 3 groups of viruses. The association of baseline characteristics with the risk of VRI was analyzed using Cox proportional cause-specific hazards model. For models involving all VRIs by different virus groups for a patient (whether at the same time or not), a robust sandwich estimator of the variance of the parameters was used to account for potential correlation at the patient level. Given patients' follow-up, all time-to-event data were censored at 36 months after transplant. Analyses were performed using the R statistical software version 2.15.2.

Results

With a median follow-up of 23 months, 166 VRIs were diagnosed in 131 of 378 patients in a median of 4 months after HSCT; among these patients, 119 were diagnosed in outpatients. The 166 VRIs were distributed as follow: 16 AdV, 84 HCoV/HRV, and 66 flu-like, including 14 influenza virus, 23 PIV, 17 RSV, and 12 human MPV. Characteristics of patients and VRIs are shown in Table 1 . Clinical presentations of VRIs did not differ between the different virus types. Copathogens were present in 45% of cases.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Cohort of Transplanted Patients and Patients with VRIs per Groups: (1) AdV, (2) HCoV/HRV, and Influenza, PIVs, Human MPV, and RSV (Flu-Like)

| Characteristics | Whole Cohort | All VRI | AdV | HCoV/HRV | Flu-Like |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 378 | 166 | 16 | 84 | 66 |

| Age at transplant, yr (range) | 43 (5-68) | 39 (9-66) | 28 (15-59) | 41 (9-66) | 40 (14-66) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 140 (37) | 63 (38) | 5 (31) | 37 (44) | 21 (32) |

| Male | 238 (63) | 103 (62) | 11 (69) | 47 (56) | 45 (68) |

| Hematological disease, n (%) | |||||

| Malignancy | 326 (86.2) | 158 (95) | 16 (100) | 80 (95.2) | 62 (94) |

| Nonmalignancy | 52 (13.8) | 8 (5) | 0 | 4 (4.8) | 4 (6) |

| Stem cell source, n (%) | |||||

| Bone marrow | 82 (21.7) | 15 (9) | 1 (6) | 7 (8) | 7 (11) |

| Peripheral stem cells | 257 (68) | 141 (85) | 14 (88) | 71 (85) | 56 (85) |

| Cord blood | 39 (10.3) | 10 (6) | 1 (6) | 6 (7) | 3 (5) |

| Donor type, n (%) | |||||

| HLA-identical sibling | 181 (47.9) | 73 (44) | 6 (38) | 35 (52) | 32 (49) |

| HLA-matched unrelated | 128 (33.9) | 64 (39) | 7 (44) | 34 (40) | 23 (35) |

| HLA-mismatched unrelated | 69 (18.3) | 28 (17) | 3 (19) | 15 (18) | 10 (15) |

| Myeloablative conditioning regimen | 151 (39.9) | 37 (22) | 4 (25) | 21 (25) | 12 (18) |

| Median months from transplant to VRI (interquartile range) | 4 (2-7) | 4 (2-11) | 3 (1-5) | 4 (2-8) | |

| At time of VRI | |||||

| Active GVHD∗ | 38 (23) | 5 (31) | 21 (25) | 12 (18) | |

| Steroid dose ≥ 1 mg/kg/day | 37 (22) | 5 (31) | 18 (21) | 14 (21) | |

| Neutropenia <.5 g/L | 23 (14) | 6 (38) | 9 (11) | 8 (12) | |

| Lymphopenia <.5 g/L | 62 (38) | 9 (56) | 29 (35) | 24 (37) | |

| Pneumonia† | 55 (33) | 7 (44) | 26 (31) | 22 (33) | |

| Nosocomial VRI | 47 (28) | 7 (44) | 25 (30) | 15 (23) | |

| Copathogen‡ | 74 (45) | 12 (75) | 32 (38) | 30 (45) | |

| VRI outcome | |||||

| Hospitalization, n (%) | 51 (31) | 5 (31) | 22 (27) | 24 (36) | |

| Hypoxemia, n (%) | 17 (10) | 4 (25) | 5 (6) | 8 (12) | |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 3 (2) | 1 (6) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | |

| Death within 3 mo, n (%) | 16 (10) | 3 (19) | 6 (7) | 7 (11) |

Active GVHD was defined as GVHD not in partial or complete remission.

Pneumonia was defined as new pulmonary infiltrates on imagery.

Copathogen was defined as a second infection including opportunistic (cytomegalovirus), bacterial, or fungal infection.

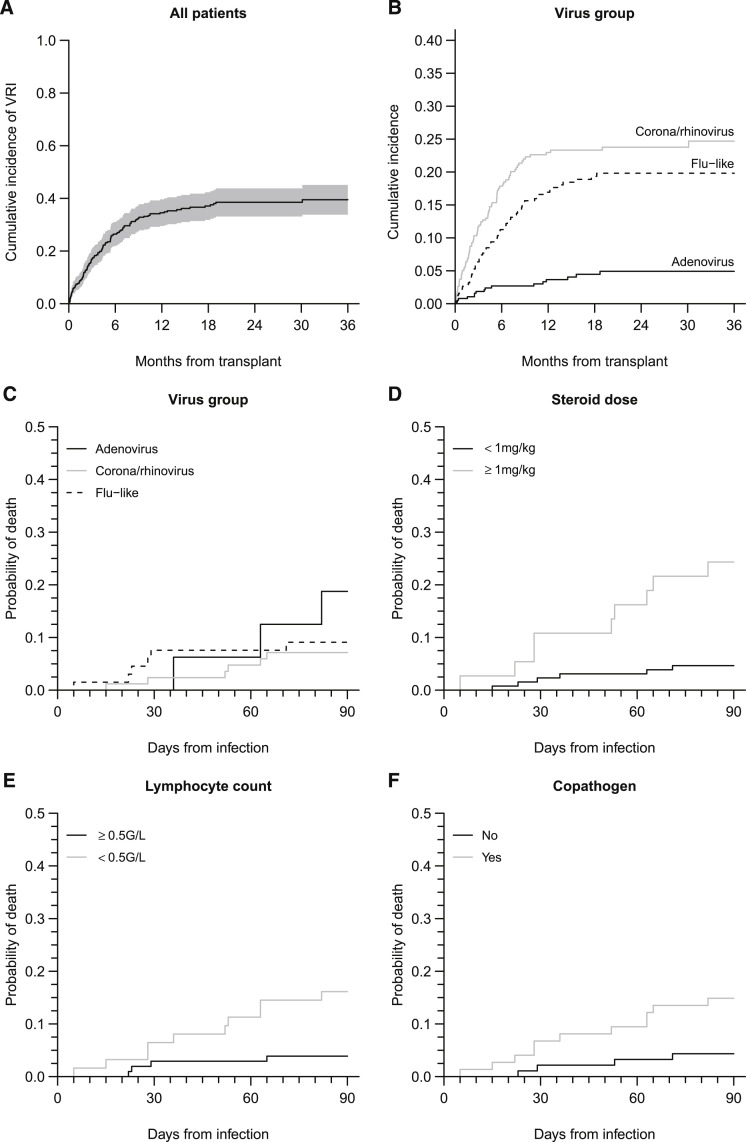

Three-year cumulative incidence of VRIs was estimated at 40% (95% confidence interval [CI], 34% to 45) (Figure 1 ). The hazard of infection by AdV was markedly lower than for the 2 other virus groups (both P < .0001), whereas infection by HCoV or HRV was more frequent than infection by flu-like viruses (P = .053).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of VRI and mortality within 3 months after VRI. (A) Cumulative incidence of first VRI from any virus, the shaded region represents the pointwise 95% confidence interval. (B) Cumulative incidence of first VRI by each of 3 virus categories. (C) Mortality incidence according to virus group: AdV, HCoR and HRV, and flu-like. (D) Mortality incidence according to steroid dose. (E) Mortality incidence according to lymphocyte count. (F) Mortality incidence according to copathogen presence. Infections with different viruses found at the same time or at different times in a same patient were all analyzed, although only the first virus of each group was considered. Because this yields to clustering, data were analyzed using generalized estimating equations with a robust variance estimator.

The only risk factor identified in univariable analysis for a first VRI or HCoV/HRV infection was a history of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) (hazard ratio [HR], 1.54; 95% CI, 1.05 to 2.27; P = .027) or chronic GVHD (HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.11 to 2.91; P = .018). In contrast, high-risk disease (NE, P = .0002), cord blood as the stem cell source (HR, 5.50; 95% CI, 1.37 to 22.1; P), and donor–recipient HLA mismatch (HR, 3.60; 95% CI, 1.30 to 10; P = .014) were risk factors for AdV; malignancies, cord blood as the stem cell source (HR, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.07 to 5.97; P = .034), and GVHD (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.93; P = .045) were risk factors for flu-like viruses.

Of 131 patients infected with VRIs, 16 died within 3 months. Among these deaths, 8 patients died of viral pneumonia in concomitance with another cause of death: bacterial and/or fungal pneumonia (RSV n = 1, AdV n = 1), uncontrolled GVHD (AdV + HRV n = 1, RSV n = 1, HCoV n = 1), graft rejection and bacterial/fungal pneumonia (RSV n = 1, AdV n = 1), or post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (HCov n = 1). Univariable analysis of risk factors for death at 3 months, identified active GVHD (odds ratio [OR], 2.99; 95% CI, 1 to 8.88; P = .049), ongoing steroid therapy at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight or higher (OR, 7.59; 95% CI, 2.61 to 22.1; P = .0002), a lymphocyte count lower than .5 g/L (OR, 5.34; 95% CI, 1.54 to 18.5; P = .008), pneumonia at the time of diagnosis (OR, 8.65; 95% CI, 1.07 to 70; P = .043), and the presence of a copathogen (OR, 4.26; 95% CI, 1.28 to 14.2; P = .018). Interestingly, the virus group and the time from HSCT had no impact on mortality. Multivariate analyses showed that 2 factors remained associated with increased overall mortality: steroid dose over 1 mg/kg body weight (OR, 8.29; 95% CI, 2.56 to 26.8; P = .0004) and a lymphocyte count lower than .5 g/L (OR, 4.73; 95% CI, 1.25 to 17.9; P = .022) (Figure 1).

Discussion

Overall incidence of VRIs in our study was consistent with the incidences reported by other teams using PCR to detect viral infection (ie, higher than that of immunofluorescence or viral culture) [9]. A higher incidence of HCoV/HRV as compared with other VRIs confirms the findings of Milano et al. [5]. However, unlike the systematic sampling in the Milano study, our samples were only collected in patients with respiratory symptoms. Patients only presenting mild symptoms probably did not seek medical attention as often as those with more severe infection. This selection bias can explain (1) that all patients with VRIs in our study seem to have similar clinical presentation, including similar pneumonia prevalence, and (2) an underestimation of general VRI incidence. Our study includes patients followed up to 3 years after transplantation showing that VRIs continue to occur at a high frequency in the late post-transplant phase. Overall, the long-term data on VRIs after allogeneic HSCT is limited. Martino et al. [2] reported a 2-year incidence of VRIs detected by immunofluorescence or viral culture close to our results (29% at 2 years versus 40% at 3 years in our study). Virus repartition differed from ours with a lower frequency of HRV, which can be attributed to the lower sensitivity of their detection method [2].

Previous acute and chronic GVHD or recipient–donor HLA mismatch can be considered as surrogate markers of immunity and increased the probability of VRI diagnosis, suggesting that some patients are more susceptible to VRIs. Both have been previously described as predisposing factors of viral infection 2, 8, 10.

Finally, the mortality rate attributable to VRIs was not as high as expected and was not associated with a particular virus. In this study, the cause of death could not clearly be concluded to be from VRIs: the patients who died from viral pneumonia all had other significant and potentially fatal comorbidities. We observed that risk factors for mortality in VRI patients were steroid dose and lymphopenia, as reported in other studies, although we cannot discriminate if these risk factors are specific for patients with VRIs or common to all transplanted patients 1, 6, 10, 11. Indeed, steroid and lymphopenia reflect a poor general condition of the patient, severe GVHD, and/or delayed immune reconstitution. Because VRI was not a risk factor for overall mortality in this cohort, one can argue that the immune status might have more of an impact than the infection itself (data not shown). It is noteworthy that in this long-term study, the time from transplantation to VRI had no effect on the prognosis, probably because the general status of the patients has a higher impact on the outcome.

Finally, although the direct mortality rate appears to be low, we have to keep in mind that fatal VRIs can occur in severely immunocompromised patients. Furthermore, we cannot exclude that later complications indirectly caused by VRIs can increase late mortality such as noninfectious respiratory disease or secondary organ failure. To conclude, we estimate that nasopharyngeal aspirates to identify VRIs in patients with respiratory symptoms can be restricted to patients with a profound immune defect or those with lower respiratory tract involvement who could benefit from careful clinical monitoring until recovery.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Authorship statement: G.S. and M.R. contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: See Acknowledgments on page 1241.

References

- 1.Ljungman P., Ward K.N., Crooks B.N. Respiratory virus infections after stem cell transplantation: a prospective study from the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:479–484. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martino R., Porras R.P., Rabella N. Prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and outcome of symptomatic upper and lower respiratory tract infections by respiratory viruses in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants for hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:781–796. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Champlin R.E., Whimbey E. Community respiratory virus infections in bone marrow transplant recipients: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7(Suppl):8S–10S. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11777103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reijans M., Dingemans G., Klaassen C.H. RespiFinder: a new multiparameter test to differentially identify fifteen respiratory viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1232–1240. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02294-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milano F., Campbell A.P., Guthrie K.A. Human rhinovirus and coronavirus detection among allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Blood. 2010;115:2088–2094. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-244152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nichols W.G., Corey L., Gooley T. Parainfluenza virus infections after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: risk factors, response to antiviral therapy, and effect on transplant outcome. Blood. 2001;98:573–578. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peck A.J., Englund J.A., Kuypers J. Respiratory virus infection among hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: evidence for asymptomatic parainfluenza virus infection. Blood. 2007;110:1681–1688. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-060343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robin M., Marque-Juillet S., Scieux C. Disseminated adenovirus infections after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Haematologica. 2007;92:1254–1257. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuypers J., Campbell A.P., Cent A. Comparison of conventional and molecular detection of respiratory viruses in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009;11:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2009.00400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ljungman P., de la Camara R., Perez-Bercoff L. Outcome of pandemic H1N1 infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Haematologica. 2011;96:1231–1235. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.041913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Fontbrune F.S., Robin M., Porcher R. Palivizumab treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1019–1024. doi: 10.1086/521912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]