Highlights

-

•

Talaromyces marneffei infections are common in immunocompromised patients from East Asia.

-

•

Blastomyces and Histoplasma antigen tests have been shown to have cross reactivity between one another and other infections.

-

•

SIADH has been shown to be caused by certain opportunistic lung infections in the absence of CNS insults.

Keywords: Talaromyces, Blastomyces, Histoplasma, Cross-reactivity, HIV

Abstract

Talaromyces marneffei is a fungal opportunistic infection usually seen in immunocompromised patients from eastern countries. In the US when examining HIV-patients for suspected fungal infections, laboratory serological tests guide therapy until cultures are available. We present the case of a 35-year-old HIV patient originally from Thailand in which urine lab results were positive for Blastomyces and Histoplasma antigen, but biopsy showed T. marneffei. Concomitantly the patient presented with hyponatremia which was deemed to be from SIADH. We present the first case of a patient with T. marneffei cross reactivity with Blastomyces, Histoplasma and SIADH due to pulmonary disease.

Introduction

Endemic to Southeast Asia, East Asia and China, Talaromyces marneffei is a dimorphic fungus capable of causing systemic fungal infections in immunocompromised patients (Supparatpinyo et al., 1994). Since its discovery in the 1950s, the majority of cases have been documented in HIV patients with low CD4 counts. In northern Thailand, T. marneffei is the fourth most prevalent opportunistic infection in this population (Chariyalertsak et al., 2001). Clinical manifestations include fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, cough, and hepatosplenomegaly (Wu et al., 2008). While the frequency of T. marneffei infection has decreased with the advent of retroviral therapy, if left untreated the infection frequently leads to respiratory failure with a poor prognosis.

In the U.S. patients with HIV infection usually undergo testing for endemic fungal infections such as Blastomyces, Histoplasma, Coccidioides and Paracoccidioides. Indirect serological results help to make faster decisions given that cultures take several days or weeks to grow. Clinical and geographic context plays a particularly important role because some of these tests have been shown to have cross-reactivities. Pulmonary infection either by fungi, bacteria or virus has been observed to cause concomitant hyponatremia, with inappropriate levels of anti-diuretic hormone (SIADH) often found as the underlying etiology. The exact mechanism is not understood but hypoxemia and hypercapnia are thought to play an important role in the pathophysiology (Rose et al., 1984).

In the following, we describe a T. marneffei infection with unusual laboratory and clinical characteristics.

Case

The patient was a 35-year-old male from Thailand who presented with generalized weakness and fever. His past medical history was relevant for HIV infection (since age 21) on HAART (bictegravir, emtricitabine & tenofovir alafenamide). Two weeks prior to his admission, he had travelled to Chicago, Las Vegas and Utah. During this time, he developed a productive cough with blood-tinged sputum, subjective fever, chills, and anorexia with associated weight loss.

On physical exam, he was noted to have multiple erythematous, raised, scaly/crusted lesions on the face, neck and abdomen (Figure 1 ), as well as concomitant cervical lymphadenopathy. Initial laboratory studies revealed hyponatremia [Na 121 mmol/L] and hypochloremia [88 mmol/L] with normal creatinine [0.59 mg/dl]. Hepatic transaminases and alkaline phosphatase were elevated [AST 269 U/L, ALT 89U/L, Alk Phos 1209 U/L, Bili 0.9 mg/dl] and cell count was within normal limits [WBC 5.7 103/uL, RBC 4.5103/uL, Platelets 208 103/uL]. The patient had received normal saline in the emergency department without improvement in his sodium level. Subsequent tests showed increased urine osmolality [491 mOsm/Kg], decreased serum uric acid [5 mg/dl] and increased urine sodium [112 mEq/L] despite volume replacement and euvolemic clinical status.

Figure 1.

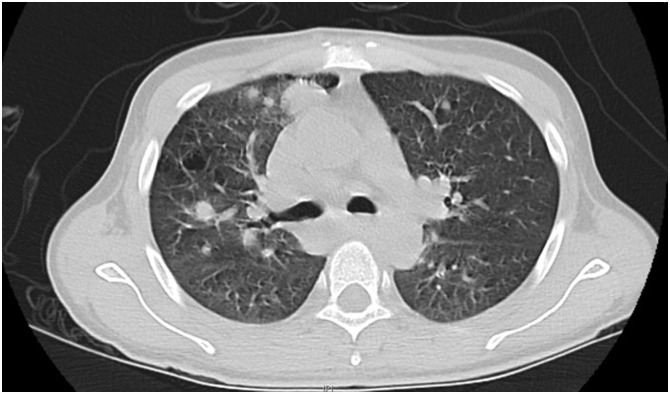

Computed Tomography showing multiple centimeter and sub-centimeter intraparenchymal nodules and perihiliar pulmonar lymphadenopathy.

HIV viral load was 3.12 * 106 copies/mL and CD4 count was 8 cells/μL. Right upper quadrant ultrasound revealed hepatomegaly and a chest x-ray reported bilateral peri-tracheal soft densities up to 3 cm in diameter, interstitial markings, and bilateral pulmonary nodules. Chest CT scan without contrast showed patchy pulmonary densities and multiple peri-hilar nodules (Figure 2 ). CT scan with contrast of the head and neck did not reveal acute intracranial abnormalities but did show cervical lymphadenopathy. Gram stain smear and culture of the sputum were negative. Respiratory viral panel including influenza, parainfluenza, coronavirus and RSV was negative. Legionella urine antigen was negative. Bacterial blood cultures and gram stain were negative. QuantiFERON gold and three sputum samples for AFB/culture were negative for tuberculosis. Serological testing for Cryptococci and Blastomyces were negative. However, urine antigen testing for both Blastomyces and Histoplasma were positive. Finally, a biopsy of one of the cutaneous lesions demonstrated dermal and subcutaneous neutrophil and histiocyte infiltrate with the presence of intracellular yeast, findings which were consistent with T. marneffei.

Figure 2.

Multiple facial erythematous papular lesions.

Discussion

T. marneffei infections typically manifest in severely immunocompromised patients. Current guidelines recommend that in HIV patients from endemic countries with a CD4 count <100 cells/μL, primary preventive therapy with itraconazole should be initiated (Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents, 2019). Clinical manifestations appear to vary depending on the severity and underlying etiology of immune compromise in the patient, differing between HIV vs. non-HIV causes such as malignancies or transplant patients. Fever, splenomegaly, anemia, transaminitis, and absence of leukocytosis seem to be more frequently found in HIV-positive patients (Kawila et al., 2013). In our case, clinical findings included fever, neck lymphadenopathy, and respiratory symptoms. Laboratory work demonstrated transaminitis along with a CD4 count of 8 cells/μL.

An initial laboratory test for endemic fungi can guide initial treatment towards early antifungal medication. However, cross-reactivity between antigens in various fungal infection detection tests is well-documented, and cross reactions between Histoplasma and Blastomyces antigens are the most common (Wheat et al., 1986). Others have been described, such as that of Histoplasma antigen in patients with sporotrichosis (Assi et al., 2011). In our case, urine antigen testing results for both Histoplasma and Blastomyces were positive, serum testing was negative.

It is of note that the sensitivities of the Blastomyces and Histoplasma antigen detection test in urine are approximately 80% and 89% respectively. Specificity is around 90% for both tests, usually having to rule out each other as the main confounder (Cunningham et al., 2015, Frost and Novicki, 2015). HIV status can affect tests based on antibody detection. Since the tests used to guide therapy are based on antigen detection, sensitivity is unlikely to be affected by HIV infection. These infections in their disseminated forms will receive amphotericin-B with itraconazole. However, differentiation is important given that blastomycosis is treated for a year versus talaromyces which is treated for 12 weeks (Sirisanthana et al., 1998, Saccente and Woods, 2010).

SIADH is an exclusion diagnosis that requires an extensive work up to rule out other etiologies including adrenal insufficiency, thyroid disease, and volume depletion (Shu et al., 2018). ADH is produced on the paraventricular thalamic nucleus and thus classically this syndrome is observed after neurological insults that cause an excess in ADH. Nevertheless, it has been observed that respiratory tract infections can cause inadequate ADH secretion and these are the most common infections in HIV patients. Increase in the A-a gradient and hypoxia/hypercapnia-induced ADH secretion are some of the non-osmotic mechanisms thought to trigger elevations in ADH in this population. It has been proposed that hypercapnic acidosis and hypoxemia induce central release of vasopressin through peripheral chemoreceptors and baroreceptors stimulation respectively (Rose et al., 1984, Dreyfuss et al., 1988). Tuberculosis, cryptosporidium, plasmodium infections and Pneumocystis pneumonia have been previously reported as pulmonary infections causing SIADH. It is of note that HIV by itself could contribute to SIADH. But the mechanism underlying this infection is usually mediated by HIV induced thyroid and adrenal insufficiency. In our case, the patient had increased urinary sodium, decreased serum osmolality, normal cortisol and TSH levels and absence of neurological affect, leaving the pulmonary fungal infection as one of the explanations for inadequate ADH secretion.

In conclusion, laboratory work up for endemic fungal infection can have false positive results with infections such as Talaromyces. This cross reactivity is especially important when assessing patients from endemic countries. Manifestations of T. marneffei infection are diverse, and disease description is limited due to the small number of cases. A novel manifestation observed in our patient was the presence of SIADH likely secondary to the respiratory Talaromyces infection. To our knowledge, this is the first case reporting systemic mycosis due to Talaromyces marneffei with associated hyponatremia secondary to SIADH and cross-reactivity with Blastomyces and Histoplasma in urine antigen testing.

Acknowledgements

Aknowledgement is given to Dr Saad, Peguy who proof read this manuscript.

Ethical approval

Consent was obtained from patient for the publication of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Consent was obtained from patient for the publication of this manuscript.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Corresponding Editor: Eskild Petersen, Aarhus, Denmark

References

- Assi Maha, Lakkis lass E., Wheat L. Joseph. Cross-reactivity in the Histoplasma antigen enzyme immunoassay caused by Sporotrichosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18(October (10)):1781–1782. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05017-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chariyalertsak S., Sirisanthana T., Saengwonloey O., Nelson K.E. Clinical presentation and risk behaviors of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Thailand, 1994–1998: regional variation and temporal trends. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(6):955. doi: 10.1086/319348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham L., Cook A., Hanzlicek A., Harkin K., Wheat J., Goad C. Sensitivity and specificity of Histoplasma antigen detection by enzyme immunoassay. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2015;51(September–October (5)):306–310. doi: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss D., Leviel F., Paillard M., Rahmani J., Coste F. Acute infectious pneumonia is accompanied by a latent vasopressin-dependent impairment of renal water excretion. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138(September (3)):583–589. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.3.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost Holly M., Novicki Thomas J. Blastomyces antigen detection for diagnosis and management of Blastomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(October (11)):3660–3662. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02352-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawila R., Chaiwarith R., Supparatpinyo K. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of Penicilliosis marneffei among patients with and without HIV infection in Northern Thailand: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:464. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf.

- Rose C.E., Jr., Anderson R.J., Carey R.M. Antidiuresis and vasopressin release with hypoxemia and hypercapnia in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol. 1984;247(July (1 Pt. 2)):R127–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.247.1.R127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccente M., Woods G.L. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(2):367–381. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00056-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Zhanjun, Tian Zimeng, Chen Jinglin, Ma Jianping, Abudureyimu Aihemaiti, Qian Qianqian. HIV/AIDS-related hyponatremia: an old but still serious problem. Renal Failure. 2018;40(1):68–74. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2017.1419975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirisanthana T., Supparatpinyo K., Perriens J., Nelson K.E. Amphotericin B and itraconazole for treatment of disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(May (5)):1107–1110. doi: 10.1086/520280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supparatpinyo K., Khamwan C., Baosoung V., Nelson K.E., Sirisanthana T. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in southeast Asia. Lancet. 1994;344:110. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheat J., French M.L., Kamel S., Tewari R.P. Evaluation of cross-reactions in Histoplasma capsulatum serologic tests. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23(3):493–499. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.3.493-499.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.C., Chan J.W., Ng C.K., Tsang D.N., Lee M.P., Li P.C. Clinical presentations and outcomes of Penicillium marneffei infections: a series from 1994 to 2004. Hong Kong Med J. 2008;14:103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]