Abstract

Background

The pilgrimage to Mecca and Karbala bring many Muslims to a confined area. Respiratory tract infections are the most common diseases transmitted during mass gatherings in Hajj, Umrah and Karbala. The aim of this study was to determine and compare the prevalence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and influenza virus infections among Iranian general population and pilgrims with severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) returning from Mecca and Karbala during 2013–2016.

Methods

During 2013–2016, a total of 42351 throat swabs were examined for presence of influenza viruses and MERS-CoV in Iranian general population and pilgrims returning from Mecca and Karbala with SARI by using one step RT-PCR kit.

Results

None of the patients had MERS-CoV but influenza viruses were detected in 12.7% with high circulation of influenza A/H1N1 (47.1%).

Conclusion

This study showed the prevalence of influenza infections among Iranian pilgrims and general population and suggests continuing surveillance, infection control and appropriate vaccination especially nowadays that the risk of influenza pandemic threatens the world, meanwhile accurate screening for MERS-CoV is also recommended.

Keywords: MERS coronavirus, Influenza virus, Pilgrims, General population, Iran

1. Introduction

The Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was first identified in a patient from Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) in June 2012 [1]. According to World Health Organization (WHO) report, until 21 September 2017, the number of laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV was 2081, with 722 deaths. Most of the cases originated from or had a history of travel to Middle-East. Mecca and Karbala are places in the Middle-East which are visited by Muslims especially during Hajj, Umrah and Arbaeen.

KSA hosts about 2.5 million Muslim pilgrims from more than 180 countries during the Hajj pilgrimage annually. Hajj is one of the largest mass gatherings of its kind in the world. Umrah is a visit to the holy sites in KSA the same as Hajj but it can be occurred at any time during the year. During the Hajj, respiratory tract infections are the leading cause of hospitalization in KSA [2], [3].

Karbala is a holly place in Iraq which Muslims visit there during the year especially Arbaeen. Arbaeen is a Shia Muslim ritual that occurs forty days after the day of Ashura (10th day of the month of Muharram). It celebrates the death of Hussein ibn Ali, the grandson of Prophet Mohammad, who was killed on the day of Ashura. Arbaeen is the world largest annual pilgrimage as more than 20 millions of Shia Muslims gather in the city of Karbala in Iraq.

Mass gathering of people in a confined area specially Hajj and Arbaeen increases the risk of respiratory tract infections which are very common and responsible for most of the hospital admissions. After June 2012 global concern was about the potential for MERS-CoV spreading by travelers returning from the pilgrimage. For early detection of emerging respiratory viruses, the International Health Regulations Emerging Committee established a program for all countries (especially those with returning pilgrims) to strengthen their surveillance to detect and report any new cases.

However KSA has been reported the majority of MERS-CoV cases (>80%) since 2012, but in the 6.5 million pilgrims in Hajj 2012 and 2013 no MERS-CoV cases were reported [4].

Influenza viruses are important human respiratory pathogens with high morbidity and mortality that cause both seasonal and endemic infections. Nowadays emergence of H5N1 and H7N7 is the concern for influenza pandemic. Different studies have shown a high incidence of influenza virus infection during the Muslim Hajj pilgrimage [5], [6] but there is no published data about the prevalence of respiratory virus infections during Arbaeen.

Among Hajj pilgrims, influenza is the most common vaccine preventable virus infection, but its epidemiology is poorly understood in mass gatherings [7]. Beside detection of MERS-CoV, we designed this study to investigate about the importance of influenza vaccination in general population and pilgrims.

In Iran, the influenza season starts in late November and lasts until late April, peaking in January and February. The National Influenza Center (NIC) in Iran, located at Virology Department, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, examines clinical samples from patients with severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) for influenza virus surveillance throughout the year in general population and/or pilgrims.

After MERS detection in 2012, all suspected cases were tested in NIC and the first MERS case, a 52 year old woman with a history of hypertension, was confirmed in May 2014, Iran [8]. With continues surveillance totally six MERS cases were identified in Iran which the last one was in March 2015.

The study's primary aim was screening the Iranian pilgrims and general population with SARI for detection of MERS-CoV during 2013–2016. The second aim was to assess the prevalence of influenza virus infections in these patients and the final aim was to comparison of influenza and MERS-CoV circulation between general population and pilgrims.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Respiratory specimens

Throat swab specimens according to Ministry of Health protocol were collected from a total of 42351 patients with SARIs. Of them, 38511 specimens were collected from general population and 3840 specimens were taken from arriving pilgrims at Emam Khomeini Airport in Tehran, 2013–2016. Throat swabs were collected in viral transport media and immediately transported to NIC, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

2.2. Molecular diagnosis

Total nucleic acids were purified from a 200 μl sample using High Pure Viral Nucleic Acid kit (Roche, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each sample was tested independently in a 25 μl reaction for influenza A/B and MERS-CoV using QuantiFast Probe RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen, Germany). MERS-CoV was tested with targeting the upstream region of the E gene (UpE) for screening and the open reading frame 1b for confirmation [9].

3. Results

In total 42351 patients with SARIs were included in this study which 3840 were returning Iranian pilgrims from Mecca and Karbala and 38511 were patients with SARI who admitted to local hospitals. Iranian pilgrims had symptoms upon arrival or a week later, thereby indicating that the respiratory infections were acquired during the pilgrimage.

Of 3840 pilgrims, 499 (13%) were positive for influenza viruses. Influenza A/H1N1, B and A/H3N2 accounted for 51.7% (258/499), 27% (135/499) and 20% (100/499) of the virus positive samples, respectively.

Of 38511 patients in general population, 4868 (12.6%) were positive for influenza viruses. Influenza A/H1N1, B and A/H3N2 accounted for 46.7% (2272/4868), 20.1% (981/4868) and 32.7% (1594/4868) of the virus positive samples. MERS-CoV was not detected in these patients.

During the years of study in all patients, circulating influenza strains differed but the pattern was similar in both pilgrims and general population.

In January 2013, A/H1N1 viruses predominated while since February influenza B viruses were the most common strains until April 2013. At the end of the year, during November and December 2013, A/H3N2 viruses became predominant until February 2014, but in March and April 2014 influenza B viruses were dominated. In May 2014 besides influenza B, A/H1N1 had a rise and during June and July both influenza A/H1N1 and B viruses had similar circulation.

The last month of the year 2014, showed similar circulation of three strains until May 2015, but in January 2015 A/H1N1and in March and April influenza B viruses were predominant strains with co-circulation of the other viruses. In October 2015, influenza A/H1N1 and A/H3N2 viruses had similar circulation but in November and December 2015, A/H1N1 became predominant strain.

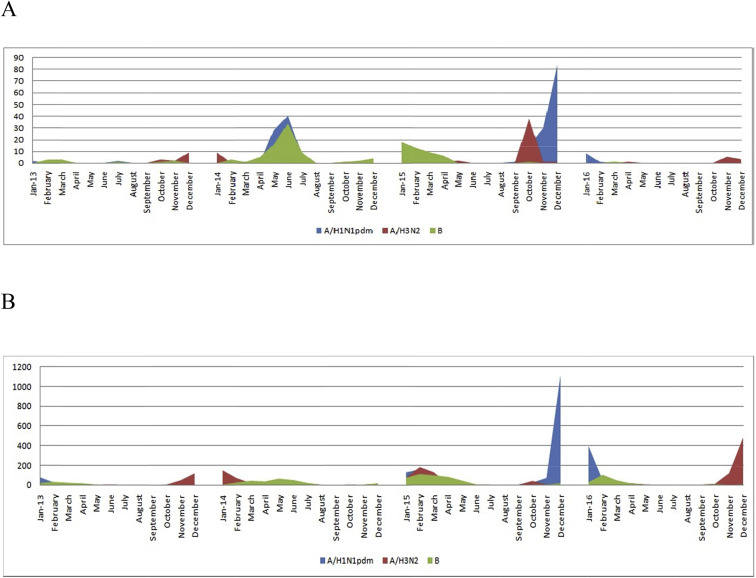

In January 2016, A/H1N1 was common with co-circulation of A/H3N2 and B viruses. In February there was a decrease in A/H1N1 circulation with a slight increase in A/H3N2 and a sharp rise in B viruses. In March 2016 influenza B viruses were common but in April and October A/H3N2 and B viruses had similar circulation while in November and December 2016, A/H3N2 virus was predominant. Fig. 1 shows the prevalence of different influenza strains during the months of the years (2013–2016).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of influenza virus strains in general population (A) and returning Iranian pilgrims (B) during the months of the years (2013–2016).

In 2014 dual infections of influenza A/H1N1and B viruses were detected in three pilgrims returning from Karbala in May and one pilgrim arriving from Karbala in June. Four dual infections of influenza A/H1N1 and B viruses were detected in June and July in non-pilgrim patients.

During 2015 six dual infections of influenza A/H3N2 and B viruses were detected which two were in pilgrims returning from Umrah in February and Hajj in October and four were detected in February, March, June and October in non-pilgrim patients.

Six dual infections of influenza A/H1N1 and B viruses were identified in general population in February, November and December 2015. Since January until March 2015, four dual infections of influenza A/H1N1 and A/H3N2 were detected.

In 2016 just in non-pilgrim patients three dual infections of influenza A/H1N1 and A/H3N2 viruses were detected in November.

During the years of this study from 3840 Iranian pilgrims, 46.1% (1773/3840) returned from Karbala, 35.2% (1355/3840) came from Umrah and 18.7% arrived from Hajj. We did not have any pilgrims returning from Mecca in 2016 but just 4.8% (185/3840) came from Karbala.

More information about the prevalence of different influenza strains in Hajj, Umrah, Karbala and general population are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Prevalence of influenza virus strains in general population (GP) and returning Iranian pilgrims from Hajj, Umrah and Karbala during 2013–2016.

| 2013, Total no = 9274 |

2014, Total no = 7611 |

2015, Total no = 16174 |

2016, Total no = 9292 |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hajj | Umrah | Karbala | GP | Hajj | Umrah | Karbala | GP | Hajj | Umrah | Karbala | GP | Karbala | GP | |

| Total patients | 544 | 141 | 268 | 8321 | 87 | 366 | 528 | 6630 | 724 | 205 | 792 | 14453 | 185 | 9107 |

| Influenza positive | 3 | 6 | 21 | 392 | 2 | 137 | 34 | 653 | 54 | 49 | 168 | 2430 | 19 | 1372 |

| A/H1N1 | – | 1 | 5 | 116 | – | 73 | 6 | 125 | 15 | 16 | 133 | 1577 | 9 | 454 |

| A/H3N2 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 173 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 272 | 38 | 5 | 15 | 432 | 9 | 717 |

| B | 2 | 2 | 6 | 103 | 1 | 56 | 18 | 256 | 1 | 28 | 20 | 421 | 1 | 201 |

4. Discussion

This paper showed the results of study of MERS-CoV and influenza virus infections among pilgrims and non-pilgrim patients with SARI during 2013–2016.

Each year more than 5 million Muslims travel from all over the world to participate in Hajj and Umrah. Approximately more than one million pilgrims travel from Iran to KSA annually. In recent years more than 10 million Iranian pilgrims have been gathering during Arbaeen in Karbala. In this study 46.1% (1773/3840) of pilgrims returned from Karbala which 13.6% were influenza positive with A/H1N1 predominance. In a study on 177 Iranian pilgrims to Karbala who admitted to Iraqi hospitals, 3.39% suffered from respiratory infections [10]. In another study from a total of 26574 pilgrims admitted to Iranian clinics in Iraq, the main cause was acute respiratory infections (48%) [11].

Generally performing the pilgrimage in a confined area is associated with an increased occurrence of respiratory infections in the pilgrims. Transmission of different infectious diseases during mass gatherings in holly places has a global effect when pilgrims return to their country. In 1989 a meningococcal disease outbreak and its global spread during the Hajj lead to this fact that meningococcal vaccine became a mandatory vaccine for all pilgrims [12]. According to the vaccination protocol in Iran, all pilgrims had received meningococcal vaccination, but influenza vaccination is not mandatory and we do not have data about its vaccination in this group. However in a review by Gautret et al. no remarkable effect of influenza vaccination on the influenza infection of pilgrims was found. Apparently this lake of efficiency of influenza vaccine might be the result of mismatch between circulating influenza viruses with vaccine strains [2].

Influenza viruses are common respiratory viruses with high mortality and morbidity especially in young children and elderly. In Iran influenza viruses are circulating throughout the year with a big peak during cold months. Since 2012 besides influenza virus screening NIC examines clinical samples for MERS-CoV detection from suspected patients throughout the year in general population and/or pilgrims.

We previously reported that a cluster of MERS-CoV was detected in Kerman/Iran in 2014 among nonpilgrims [8]. Current study showed that among the population screened, no cases were positive for MERS-CoV. These results were in accordance with previous studies which have performed among pilgrims of different countries. A cohort of 5235 pilgrims attending the 2013 Hajj showed the lack of MERS-CoV in nasal carriage [13]. In a study on 154 French Hajj pilgrims in 2012, in spite of high rate of respiratory infections, MERS-CoV was not detected [14]. These findings suggest that MERS-CoV in its current form has poor interhuman transmission and may not have the pandemic potential as seen in influenza A/H1N1 in 2009. However investigation about a highly fatal human coronavirus is necessary as it is a challenge and little is known about its importance, epidemiology and zoonotic transmission.

In pilgrims of this study influenza B accounted for 27% (135/499) and influenza A for 71.7% (358/499) of positive influenza results in contrast to findings by Balkhy et al., in 2003, that 90% of pilgrims had influenza B and 10% had influenza A [15].

The results of a UK study with paired serum samples collected before and after the Hajj using hemagglutination inhibition test, showed that 38% of UK pilgrims had influenza infection during the Hajj 2003 [16]. In another study during Hajj 2005, 14% of UK pilgrims with respiratory infections had influenza virus [17].

Rashid et al., in 2008 performed a comparative study in symptomatic UK and Saudi pilgrims which found infections in 25% and 13% of their pilgrims respectively. Rhinoviruses were detected in half of UK pilgrims, followed by influenza virus but in Saudi pilgrims 78.5% had influenza virus infection [18].

In 2009, Alborzi et al. reported that 9.8% of Iranian Hajj pilgrims with respiratory infections had influenza [19]. In 2012, 305 Iranian pilgrims with respiratory infections returning from Hajj were assessed for detection of A/H1N1pdm which just five patients (1.69%) were positive [20]. In a survey on serum samples of 338 Iranian pilgrims before and after Hajj with ELISA, 3.6% were influenza positive [21].

In another Iranian study on serum samples of Hajj pilgrims in 2004–2005, before departure and two weeks after respiratory infections, there was a 21.5% seroconversion for influenza viruses. While virus culture on their sputum was 13.3% influenza positive [22]. In a study on 275 symptomatic Iranian Hajj pilgrims, 25 (9.1%) were influenza positive by virus culture whereas 33 (12%) had influenza with RT-PCR test [23].

The findings of this research showed that influenza virus infection was the cause of respiratory infections in 499 of 3840 (13%) of Iranian pilgrims. In a similar study in Kashmir, north India during 2014–15 among returning Hajj and Umrah pilgrims with respiratory illness, none of the 300 participants tested positive for MERS-CoV; however, 33 (11%) tested positive for influenza viruses [24].

In general population, of 38511 SARI patients, 4868 (12.6%) were influenza positive during the years of this study with different circulation of the subtypes as seen in other studies:

Timmermans et al. performed a study on 586 outpatients with influenza-like-illness in western Cambodia between May 2010 and December 2012. Influenza was found in 168 cases (29%). Dominant influenza subtypes were A/H1N1 in 2010, influenza B in 2011 and influenza A/H3N2 in 2012 [25].

In a study by Mancinelli et al. a total of 133 respiratory specimens positive for the influenza A and B viruses were subtyped during the 2012–2013 influenza season in Italy. Influenza B was slightly more prevalent (53.38%) than influenza A (46.62%) and the most common subtype was A/H1N1 (87.1%) while only 12.9% were A/H3N2 [26].

In a ten year (2004–2014) study of influenza surveillance in northern Italy, the same as our study influenza A/H3N2 was prominent during 2013–2014 [27].

The results of this study showed similar pattern of virus circulation in pilgrims and non-pilgrims SARI patients. As influenza has high morbidity and mortality, its vaccination is recommended for general population especially for high risk groups and pilgrims before going to pilgrimage.

Finally accurate screening and testing for MERS-CoV and other respiratory viruses including influenza, is necessary for early diagnosis to prevent virus transmission and to do effective treatment. As a final point lack of demographic and clinical data was the most important limitation of this study.

Author contributions

Jila Yavarian performed the analyses of the data and wrote the paper. Nazanin Zahra Shafiei Jandaghi reviewed the paper critically, and comments were included. Maryam Naseri performed the tests. Peyman Hemmati, Mohammadnasr Dadras were responsible for epidemiological investigation and data collection. Mohammad Mehdi Gouya and Talat Mokhtari Azad were responsible for study design.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank all staff in National Influenza Center, Virology Department, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gautret P., Benkouiten S., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Hajj-associated viral respiratory infections: a systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:92–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Ghamdi S.M., Akbar H.O., Qari Y.A., Fathaldin O.A., Al-Rashed R.S. Pattern of admission to hospitals during Muslim pilgrimage (Hajj) Saudi Med J. 2003;24(10):1073–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Memish Z.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A. Public health management of mass gatherings: the Saudi Arabian experience with MERS-CoV. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91 doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.132266. 899–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balkhy H.H., Memish Z.A., Bafaqeer S., Almuneef M.A. Influenza a common viral infection among Hajj pilgrims: time for routine surveillance and vaccination. J Travel Med. 2004;11:82–86. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.17027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shafi S, Rashid H, Ali K, Sheikh A. Enhanced surveillance of influenza and Other respiratory viruses among UK pilgrims to Hajj 2005. Annual Conference, September 2005. Warwick, UK. (abstract available from: URL: http://www.iccuk.org/media/articles/misc/study_of_influenza.htm).

- 7.Rashid H., Haworth E., Shafi S., Memish Z.A., Booy R. Pandemic influenza: mass gatherings and mass infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:526–527. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70186-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yavarian J., Rezaei F., Shadab A., Soroush M., Gooya M.M., Mokhtari Azad T. Cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in Iran, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(2):362–364. doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corman V.M., Eckerle I., Bleicker T., Zaki A., Landt O., Eschbach-Bludau M. Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. EuroSurveill. 2012;17(39):pii=20288. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.39.20285-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadeghi S., Heidari A., Fazli H., Rezaei M., Sheikhzadeh J. The most frequent causes of hospitalization of Iranian pilgrims in Iraq during a 5-month period in 2012, and their outcome. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17(11):e12862. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.12862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mousavi J., Jafari F. Prevalence of diseases in pilgrims referring to Iranian clinics in Iraq. Int J Travel Med Glob Health. 2016;4(1):31–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Memish Z.A., Venkatesh S., Ahmed Q.A. Travel epidemiology: the Saudi perspective. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:96–101. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Memish Z.A., Assiri A., Almasri M., Alhakeem R.F., Turkestani A., Al Rabeeah A.A. Prevalence of MERS-CoV nasal carriage and compliance with the Saudi Health recommendations among pilgrims attending the 2013 Hajj. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(7):1067–1072. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gautret P., Charrel R., Belhouchat K., Drali T., Benkouiten S., Nougairede A. Lack of nasal carriage of novel corona virus (HCoV-EMC) in French Hajj pilgrims returning from the Hajj 2012, despite a high rate of respiratory symptoms. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:315–317. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balkhy H.H., Memish Z.A., Bafaqeer S., Almuneef M.A. Influenza a common viral infection among Hajj pilgrims: time for routine surveillance and vaccination. J Travel Med. 2004;11:82–86. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.17027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bashir H El., Haworth E., Zambon M., Shafi S., Zuckerman J., Booy R. Influenza among UK pilgrims to Hajj. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;2004(10):882–883. doi: 10.3201/eid1010.040151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rashid H., Shafi S., Booy R., El Bashir H., Ali K., Zambon M.C. Influenza and respiratory syncytial Virus infections in British Hajj pilgrims. Emerg Health Threats J. 2008;1:e2. doi: 10.3134/ehtj.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rashid H., Shafi S., Haworth E., Bashir H El., Memish Z.A., Sudhanva M. Viral respiratory infections at the Hajj:comparison between UK and Saudi pilgrims. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(6):569–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alborzi A., Aelami M.H., Ziyaeyan M., Jamalidoust M., Moeini M., Pourabbas B. Viral etiology of acute respiratory infections among Iranian Hajj pilgrims. J Travel Med. 2009;16(4):239–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ziyaeyan M., Alborzi A., Jamalidoust M., Moeini M., Pouladfar G.R., Pourabbas B. Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection among 2009 Hajj Pilgrims from Southern Iran: a real-time RT-PCR-based study. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:e80–e84. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imani R., Karimi A., Habibian R. Acute respiratory viral infections among Tamattu' Hajj pilgrims in Iran. Life Sci J. 2013;10:449–453. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razavi S.M., Ziaee H., Mokhtari-Azad T., Hamkar R., Doroodi T., Mirsalehian A. Surveying respiratory infections among Iranian Hajj pilgrims. Iran J Clin Infect Dis. 2007;2(2):67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moattari A., Emami A., Moghadami M., Honarvar B. Influenza viral infections among the Iranian Hajj pilgrims returning to Shiraz, Fars province. Iran Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:77–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koul P.A., Mir H., Saha S., Chadha M.S., Potdar V., Widdowson M.-A. Influenza not MERS CoV among returning Hajj and Umrah pilgrims with respiratory illness, Kashmir, north India, 2014-15. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2017;15:45–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Timmermans A., Melendrez M.C., Se Y., Chuang I., Samon N., Uthaimongko N. Human sentinel surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viral pathogens in border areas of Western Cambodia. Plos One. 2016;11(3):e0152529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mancinelli L., Onori M., Concato C., Sorge R., Chiavelli S., Coltella L. Clinical features of children hospitalized with influenza A and B infections during the 2012–2013 influenza season in Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:6. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1333-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosnier A., Caini S., Daviaud I., Bensoussan J.L., Stoll-Keller F., Bui T.T. Ten influenza seasons in France: distribution and timing of influenza A and B circulation, 2003–2013. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:357. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1056-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]