Abstract

Background

Since the initial description of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), we adopted a systematic process of screening patients admitted with community acquired pneumonia. Here, we report the result of the surveillance activity in a general hospital in Saudi Arabia over a four year period.

Materials and methods

All admitted patients with community acquired pneumonia from 2012 to 2016 were tested for MERS-CoV. In addition, testing for influenza viruses was carried out starting April 2015.

Results

During the study period, a total of 2657 patients were screened for MERS-CoV and only 20 (0.74%) tested positive. From January 2015 to December 2016, a total of 1644 patients were tested for both MERS-CoV and influenza. None of the patients tested positive for MERS-CoV and 271 (16.4%) were positive for influenza. The detected influenza viruses were Influenza A (107, 6.5%), pandemic 2009 H1N1 (n = 120, 7.3%), and Influenza B (n = 44, 2.7%). Pandemic H1N1 was the most common influenza in 2015 with a peak in peaked October to December and influenza A other than H1N1 was more common in 2016 with a peak in August and then October to December.

Conclusions

MERS-CoV was a rare cause of community acquired pneumonia and other viral causes including influenza were much more common. Thus, admitted patients are potentially manageable with Oseltamivir or Zanamivir therapy.

Keywords: MERS-CoV, Surveillance, Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Influenza, Community acquired pneumonia, CAP

1. Introduction

The emergence of the Middle East respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in September 2012 had attracted international attention. The virus was initially isolated from a patient with a fatal community acquired pneumonia (CAP) in Saudi Arabia [1]. Since then, multiple hospital outbreaks occurred within [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7] and outside Saudi Arabia [8], [9], [10], [11]. As of May 1st, 2017, the World Health Organization reported 1952 laboratory-confirmed cases worldwide and at least 693 related deaths [12]. A wide-spectrum of MERS-CoV infection was described and ranges from mild to severe and fulminant infections leading to severe acute respiratory disease [2], [13], [14], [15]. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the number of MERS-CoV cases was 1601 as of May 6th, 2017 [16]. Since most of the cases of MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia occurred due to intra- and inter-hospital transmissions, there was an increased amplification of the transmission [2], [3], [4], [9], [10], [11], [17]. Early detection and isolation of patients with MERS-CoV infection remains an important factor for the control of MERS-CoV transmission [18], [19]. One of the goals of the surveillance of emerging respiratory viruses is the rapid and early identification and placement of control measures [20]. Following the initial description of the disease [1], the ministry of health in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia put in place a surveillance and screening program for patients admitted with respiratory illness [21]. Similarly, we adopted universal screening of admitted patients with community acquired pneumonia. Here, we report the result of the surveillance activity in a general hospital in Saudi Arabia over a four year period.

2. Materials and methods

The study was conducted at a 350-bed general hospital, which also accepts referred patients. The hospital provides medical care for about 160,000 individuals eligible for medical care. The hospital has 5 intensive care units (cardiac, medical, surgical, pediatric, and neonatal) [22]. All admitted patients with community acquired pneumonia from 2012 to 2016 were tested for MERS-CoV. The case definition of suspected MERS-CoV was an acute febrile respiratory illness (fever, cough, or dyspnea) with radiographic evidence of pneumonia [22]. We collected data for all suspected patients using a standard Microsoft Excel data collection sheet. Both electronic and paper medical records were reviewed. We recorded the age and the date of admission and the MERS-CoV and influenza results. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2.1. MERS-CoV and influenza testing

Suspected patients had either Dacron-flocked nasopharyngeal swabs, or sputum testing for MERS-CoV. The testing was done at the Saudi Ministry of Health MERS-CoV laboratory and at the main hospital. Clinical samples were screened with real-time reverse-transcriptase (RT)—PCR as described previously [23]. The test amplified both the upstream E protein (upE gene) and ORF1a for MERS-CoV and if both assays were positive then the diagnosis of MERS-CoV was made, as described previously [14]. The influenza test was carried out at the Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare Centre, Dhahran, using the Cepheid® Xpert Flu assay multiplex real-time PCR. The tested influenza viruses were pandemic 2009 H1N1, Influenza A (other than H1N1), and Influenza B. The test was systematically carried out starting April 2015.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using Excel and descriptive analyses were done for demographic, results of the tests and the monthly number of cases. Minitab® (Minitab Inc. Version 17, PA16801, USA; 2017) was used to calculate the mean age (±SD) of patients with influenza.

3. Results

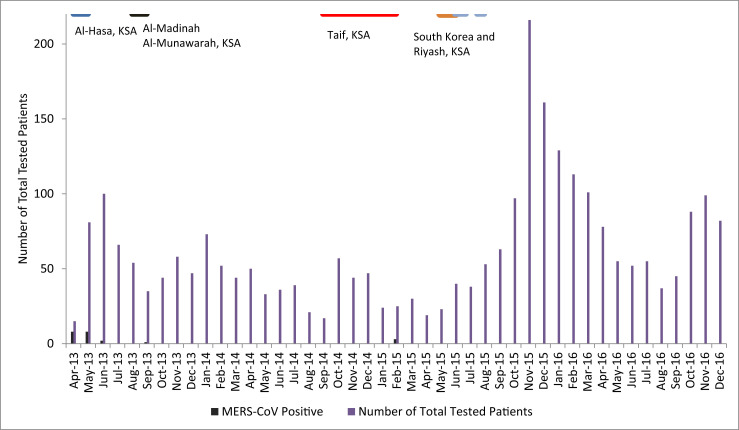

During the study period from 2013 to 2016, a total of 2657 patients were screened for MERS-CoV and only 20 (0.74%) tested positive. During the first two years (April 2013–March 2015), a total of 1013 patients were screened for MERS-CoV. Only 1.8% of them were positive for MERS-CoV (Table 1 ) and unfortunately these were not systematically screened for influenza. There was an increased number of tests in November 2015–March 2016 (Fig. 1 ).

Table 1.

Number of positive tests for influenza and MERS-CoV in relation to the study period.

| Study Period | MERS-CoV | Influenza A | H1N1 | Influenza B | Grand Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4/2013–3/2015 | 20 (1.8) | ND | ND | ND | 1092 |

| 4/2015–12/2016 | 0 (0) | 107 (6.5) | 120 (7.2) | 44 (2.6) | 1644 |

| Overall | 20 (0.74) | 2736 |

Fig. 1.

Monthly number of patients who were tested for MERS-CoV and the time of occurrence of major outbreaks.

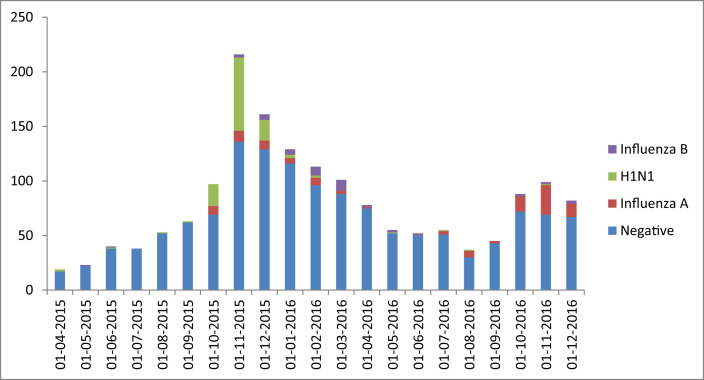

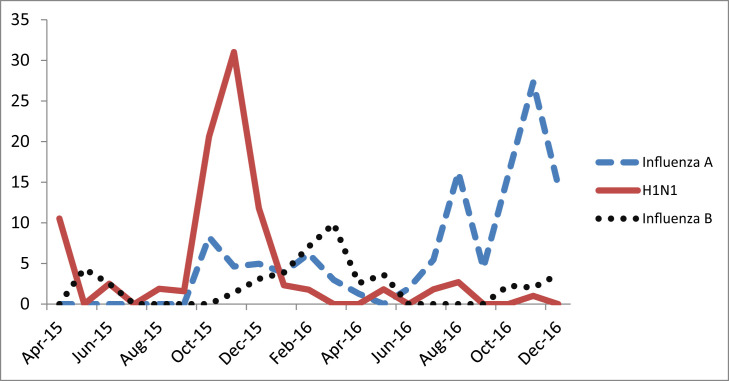

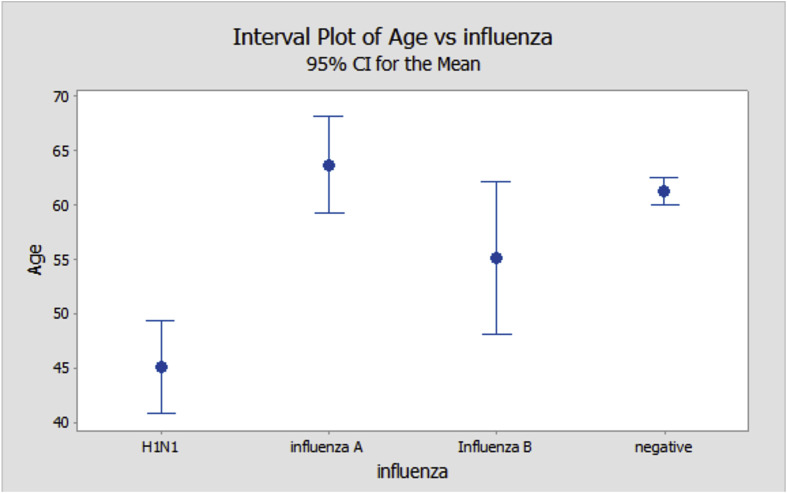

From April 2015 to December 2016, a total of 1644 patients were tested for both MERS-CoV and influenza. None of the patients tested positive for MERS-CoV and 271 (16.4%) were positive for influenza. The detected influenza viruses were Influenza A (107, 6.5%), pandemic 2009 H1N1 (n = 120, 7.3%), and Influenza B (n = 44, 2.7%) (Table 1 and Fig. 2 ). It is interesting to note the pattern of the influenza in 2015 and 2016 (Fig. 3 ). Pandemic H1N1 was the most common influenza in 2015 and influenza A other than H1N1 was more common in 2016. The 2015 influenza season peaked October to December and the 2016 season had a peak in August and then October to December (Fig. 3). There was a significant difference in the mean age (±SD; 95% CI) of patients with H1N1 and other influenza (Fig. 4 ). The mean age (±SD; 95% CI) was 45.09 (±24.32; 40.85, 49.33) for H1N1, 63.70 (±20.34; 59.21, 68.19) for influenza A, 55.11 (±25.27; 48.11, 62.12) for Influenza B, and 61.28 (±23.82; 60.03, 62.54) for influenza negative patients (P < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

Monthly influenza type from April 2015 to December 2016.

Fig. 3.

A Line graph showing the monthly number of isolated influenza by type.

Fig. 4.

Interval plot of age and 95% confidence interval of age among influenza patients.

4. Discussion

In this study, we presented the surveillance data on MERS-CoV over a four year period and the surveillance for influenza over a two year period. MERS-CoV was only detected in 20 (0.75%) from a total of 2657 patients as detailed in previous publication [22], [24]. The earliest surveillance study from Saudi Arabia was done from 1 October 2012 to 30 September 2013 and tested a total of 5065 samples [21]. In that study, the MERS positivity rate was 2% [21]. A second surveillance of MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia was conducted from April 1, 2015 to February 1, 2016 and included a total of 57,363 suspected MERS cases [25]. The study showed only 384 (0.7%) MERS-CoV positive cases [25]. In a study in the United States, two (0.4%) imported cases were detected among 490 patients-under investigation in 2013–2014 [26]. In a surveillance study of 1586 unique persons from the United Arab Emirates between January 1, 2013and April 17, 2014, 41 (3%) tested positive for MERS-CoV infection [27]. In the South Korea outbreak, 184 (1%) had MERS among 16,752 suspected cases [28]. In a small study from Saudi Arabia, MERS-CoV was not detected in 182 cases tested November 2013 and January 2014 (winter time) [29]. Thus, the overall positivity of MERS-CoV among a large cohort remains low. There is a need for a better tool to identify patients with high probability of MERS-CoV. However, a case control study and a large cohort study did not reveal significant predictor of MERS-CoV infection [22], [30].

The monthly frequency of suspected MERS cases that were tested showed variation with an apparent increase in the tested number during November 2015–March 2016. This apparent increase likely represented an increased activity of influenza during that time. There was no relation to the Hajj season as it occurred during September 21–26, 2015 (Fig. 1). In addition at that time, there were no known outbreaks in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to account for such an increase in the testing. The 2015 outbreaks occurred in Al-Hasa in May 2015 [31] and in Riyadh in August 2015 [7], [32], [33]. Previous studies had shown increased testing of patients for MERS-CoV during outbreaks [4]. In the current study, the 2015 season was predominated by 2009 pandemic H1N1 whereas influenza A was more common during 2016. Similarly, in the United States the 2014–2015 season was predominated by pandemic H1N1 and H3N2 was more common during the 2016–2017 season [34], [35].We found that influenza rather than MERS-CoV was more common among the tested patients. The findings are also consistent with other studies among travelers and pilgrims where influenza far exceeded MERS [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]. Similarly, in a small study in Saudi Arabia, influenza viruses were detected in 16% of 182 patients [29]. Similarly, among a small study of 52 suspected MERS cases in the United States of America, Influenza was the most commonly (35%) identified respiratory agent [41] and another study found influenza A and B in 11% of 296 investigated patients [26]. Thus, it is important to test for common respiratory pathogens such as influenza viruses and it should be noted that identification of a respiratory pathogen should not exclude MERS-CoV testing [42]. One report indicated co-infection with influenza and MERS in four patients [43]. However, epidemiologic differences between different countries should remain as an important predictor of the existence of MERS-CoV infection.

The mean age of patients with H1N1 was younger than the other influenza patients of at least 10 years (45.09 vs. 63.70 for influenza A, 55.11 for Influenza B, and 61.28 for influenza negative patients (P < 0.0001). The inital cases of pandemic 2009 H1N1 were also younger than the influenza negative patients [44]. In a small study of 196 patients, influenza B patients were younger than other influenza [45] and in another study the mean age was lower for patients with influenza B (16.4 yr) than (H1N1) pdm09 influenza infection. However, these studies included children and thus are not comparable with the present study [46].

Similar results were obtained in travelers returning from the Middle East. These studies showed the lack of MERS-CoV among travelers and that influenza was more common among French travelers [47], [48], Austrian returning pilgrims [40], British travelers [49], German travelers [50], and travelers to California, United States [41]. The presence of influenza infection among those travelrs stress the need for influenza vaccination in travelers, notably tfor those going for the Hajj and Umrah in Saudi Arabia.

In conclusion, MERS-CoV was a rare cause of community acquired pneumonia (CAP) and other viral causes including influenza are much more common. The epidemiology of influenza mirrored the epidemiology of influenza worldwide. The study highlights the importance of the surveillance system to elucidate the epidemiology of respiratory infections in order to formulate appropriate control measures. Inter-hospital and intra-hospital transmission of MERS-CoV infection is an important element of the transmission of this virus and it is imperative to continue to have early recognition of cases and constant application of infection control measures to abort the hospital transmissions of the virus [18], [19].

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Financial support

All authors have no funding.

References

- 1.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Fouchier R.A.M. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M., Price C.S., Al Rabeeah A.A., Cummings D.A.T. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oboho I.K., Tomczyk S.M., Al-Asmari A.M., Banjar A.A., Al-Mugti H., Aloraini M.S. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah–a link to health care facilities. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:846–854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drosten C., Muth D., Corman V.M., Hussain R., Al Masri M., HajOmar W. An observational, laboratory-based study of outbreaks of middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Jeddah and Riyadh, kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:369–377. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagbo S.F., Skakni L., Chu D.K.W., Garbati M.A., Joseph M., Peiris M. Molecular epidemiology of hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1981–1988. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almekhlafi G.A., Albarrak M.M., Mandourah Y., Hassan S., Alwan A., Abudayah A. Presentation and outcome of Middle East respiratory syndrome in Saudi intensive care unit patients. Crit Care. 2016;20:123. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1303-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balkhy H.H., Alenazi T.H., Alshamrani M.M., Baffoe-Bonnie H., Al-Abdely H.M., El-Saed A. Notes from the field: nosocomial outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in a large tertiary care hospital–Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:163–164. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Drivers of MERS-CoV transmission: what do we know? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2016;10:331–338. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2016.1150784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hijawi B., Abdallat M., Sayaydeh A., Alqasrawi S., Haddadin A., Jaarour N. Novel coronavirus infections in Jordan, April 2012: epidemiological findings from a retrospective investigation. East Mediterr Heal J. 2013;19(Suppl 1):S12–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim Y., Lee S., Chu C., Choe S., Hong S., Shin Y. The characteristics of middle eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus transmission dynamics in South Korea. Osong Public Heal Res Perspect. 2016;7:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowling B.J., Park M., Fang V.J., Wu P., Leung G.M., Wu J.T. Preliminary epidemiologic assessment of MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea, May–June 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.25.21163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; 2017. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Memish Z a, Zumla A.I., Al-Hakeem R.F., Al-Rabeeah A a, Stephens G.M. Family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2487–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Al-Rabiah F.A., Al-Hajjar S., Al-Barrak A. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albarrak A.M., Stephens G.M., Hewson R., Memish Z.A. Recovery from severe novel coronavirus infection. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:1265–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saudi Ministry of Health C and CC. MERS-CoV Statistics n.d. http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/ccc/pressreleases/pages/default.aspx.

- 17.Al-Abdallat M.M., Payne D.C., Alqasrawi S., Rha B., Tohme R.A., Abedi G.R. Hospital-Associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1225–1233. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Perl T.M. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in healthcare settings. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2015;28:392–396. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfiq J.A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection control: the missing piece? Am J Infect Control. 2014;42 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Zumla A., Gautret P., Gray G.C., Hui D.S., Al-Rabeeah A.A. Surveillance for emerging respiratory viruses. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70840-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Makhdoom H.Q., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Assiri A., Alhakeem R.F. Screening for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in hospital patients and their healthcare worker and family contacts: a prospective descriptive study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:469–474. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Hinedi K., Ghandour J., Khairalla H., Musleh S., Ujayli A. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (MERS-CoV): a case-controlstudy of hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:160–165. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corman V.M., Müller M.A., Costabel U., Timm J., Binger T., Meyer B. Assays for laboratory confirmation of novel human coronavirus (hCoV-EMC) infections. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:49. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.49.20334-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Hinedi K., Abbasi S., Babiker M., Sunji A., Eltigani M. Hematologic, hepatic, and renal function changes in hospitalized patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Int J Lab Hematol. 2017;39:272–278. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bin Saeed A.A., Abedi G.R., Alzahrani A.G., Salameh I., Abdirizak F., Alhakeem R. Surveillance and testing for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Saudi Arabia, April 2015–february 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:682–685. doi: 10.3201/eid2304.161793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider E., Chommanard C., Rudd J., Whitaker B., Lowe L., Gerber S.I. Evaluation of patients under investigation for MERS-CoV infection, United States, January 2013-October 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1220–1223. doi: 10.3201/eid2107.141888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al Hosani F.I., Pringle K., Al Mulla M., Kim L., Pham H., Alami N.N. Response to emergence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Abu dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1162–1168. doi: 10.3201/eid2207.160040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim K.H., Tandi T.E., Choi J.W., Moon J.M., Kim M.S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak in South Korea, 2015: epidemiology, characteristics and public health implications. J Hosp Infect. 2017;95:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdulhaq A.A., Basode V.K., Hashem A.M., Alshrari A.S., Badroon N.A., Hassan A.M. Patterns of human respiratory viruses and lack of MERS-coronavirus in patients with acute upper respiratory tract infections in southwestern province of Saudi Arabia. Adv Virol. 2017;2017:4247853. doi: 10.1155/2017/4247853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohd H.A., Memish Z.A., Alfaraj S.H., McClish D., Altuwaijri T., Alanazi M.S. Predictors of MERS-CoV infection: a large case control study of patients presenting with ILI at a MERS-CoV referral hospital in Saudi Arabia. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El Bushra H.E., Abdalla M.N., Al Arbash H., Alshayeb Z., Al-Ali S., Latif Z.A.-A. An outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) due to coronavirus in Al-Ahssa Region, Saudi Arabia, 2015. East Mediterr Health J. 2016;22:468–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balkhy H.H., Alenazi T.H., Alshamrani M.M., Baffoe-Bonnie H., Arabi Y., Hijazi R. Description of a hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in a large tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1147–1155. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Dorzi H.M., Aldawood A.S., Khan R., Baharoon S., Alchin J.D., Matroud A.A. The critical care response to a hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection: an observational study. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:101. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0203-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davlin S.L., Blanton L., Kniss K., Mustaquim D., Smith S., Kramer N. Influenza activity - United States, 2015-16 season and composition of the 2016-17 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:567–575. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6522a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.CDC. 2016-2017 Influenza Season n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/pdf/External_F1716.pdf (accessed April 30, 2017).

- 36.Refaey S., Amin M.M., Roguski K., Azziz-Baumgartner E., Uyeki T.M., Labib M. Cross-Sectional survey and surveillance for influenza viruses and MERS-CoV among egyptian pilgrims returning from Hajj during 2012-2015. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2016 doi: 10.1111/irv.12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atabani S.F., Wilson S., Overton-Lewis C., Workman J., Kidd I.M., Petersen E. Active screening and surveillance in the United Kingdom for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in returning travellers and pilgrims from the Middle East: a prospective descriptive study for the period 2013–2015. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koul P.A., Mir H., Saha S., Chadha M.S., Potdar V., Widdowson M.-A. Influenza not MERS CoV among returning Hajj and Umrah pilgrims with respiratory illness, Kashmir, north India, 2014–15. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2017;15:45–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gautret P., Benkouiten S., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Hajj-associated viral respiratory infections: a systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:92–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aberle J.H., Popow-Kraupp T., Kreidl P., Laferl H., Heinz F.X., Aberle S.W. Influenza A and B viruses but not MERS-CoV in Hajj pilgrims, Austria, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:726–727. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shahkarami M., Yen C., Glaser C., Xia D., Watt J., Wadford D.A. Laboratory testing for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, California, USA, 2013-2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1664–1666. doi: 10.3201/eid2109.150476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.CDC. Interim Guidelines for Clinical Specimens from PUI | CDC n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html (accessed May 7, 2017).

- 43.Alfaraj S.H., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Alzahrani N.A., Altwaijri T.A., Memish Z.A. The impact of co-infection of influenza A virus on the severity of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J Infect. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Abed M., Saadeh B.M., Ghandour J., Shaltaf M., Babiker M.M. Pandemic influenza A (2009 H1N1) in hospitalized patients in a Saudi Arabian hospital: epidemiology and clinical comparison with H1N1-negative patients. J Infect Public Health. 2011;4 doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaji M., Watanabe A., Aizawa H. Differences in clinical features between influenza A H1N1, A H3N2, and B in adult patients. Respirology. 2003;8:231–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Purakayastha D.R., Gupta V., Broor S., Sullender W., Fowler K., Widdowson M.-A. Clinical differences between influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 & influenza B infections identified through active community surveillance in North India. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:962–968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gautret P., Charrel R., Benkouiten S., Belhouchat K., Nougairede A., Drali T. Lack of MERS coronavirus but prevalence of influenza virus in French pilgrims after 2013 Hajj. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:728–730. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griffiths K., Charrel R., Lagier J.-C., Nougairede A., Simon F., Parola P. Infections in symptomatic travelers returning from the Arabian peninsula to France: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:414–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas H.L., Zhao H., Green H.K., Boddington N.L., Carvalho C.F.A., Osman H.K. Enhanced MERS coronavirus surveillance of travelers from the Middle East to England. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1562–1564. doi: 10.3201/eid2009.140817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.German M., Olsha R., Kristjanson E., Marchand-Austin A., Peci A., Winter A.-L. Acute respiratory infections in travelers returning from MERS-CoV-affected areas. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1654–1656. doi: 10.3201/eid2109.150472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]