Abstract

Objective

Knowledge about the etiology of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is essential for adequate management. Presently, few studies about CAP are available from Southeast Asia. This study aimed to investigate the etiology, severity, and outcome of CAP in the most populous Southeast Asia country, Indonesia.

Methods

From October 2007 to April 2009, adult patients admitted with CAP to two hospitals in Semarang, Indonesia, were included to detect the etiology of CAP using a full range of diagnostic methods. The severity of disease was classified according to the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI). The outcome was assessed as 30-day mortality.

Results

In total, 148 consecutive patients with CAP were included. Influenza virus (18%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (14%), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (13%) were the most common agents identified. Other Gram-negative bacilli, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Chlamydia pneumoniae each accounted for 5%. The bacteria presented wild type antibiotic susceptibility profiles. Forty-four percent of subjects were high-risk patients (PSI class IV-V). The mortality rate (30%) was significantly associated with disease severity score (P<0.001), and with failure to establish an etiological diagnosis (P=0.027). No associations were found between etiology and underlying diseases, PSI class, nor mortality.

Conclusions

Viruses and Gram-negative bacilli are dominant causes of CAP in this region, more so than S. pneumoniae. Most of the bacteria have wild type susceptibility to antimicrobial agents. Patients with severe disease and those with unknown etiology have a higher mortality risk.

Keywords: Etiology, Community-aquired pneumonia, Asia, Virus, Gram-negative bacilli, Tuberculosis

1. Introduction

Knowledge about the etiology of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is essential for patient management.1 However, only few studies on CAP are available from Southeast Asia. Many countries in Southeast Asia have no published or peer reviewed studies on CAP, including Indonesia, Brunei, Myanmar, Cambodia, East Timor, Laos, Vietnam, and most published studies used limited or unstandardized microbiological methods.2, 3, 4, 5 The etiology of CAP has been reported to differ in different geography and demography settings, thus, the management should not directly be adopted from other countries. Local data should be provided using a systematic and standardized method. This study aimed to describe the current etiology of CAP using a full range of diagnostic methods. Antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial pathogens, underlying diseases, severity and outcome of these CAP patients were analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

A prospective cohort study was performed in Dr. Kariadi Hospital (an 850-bed academic hospital) and in Semarang Municipal Hospital (a 130-bed secondary hospital).

2.2. Subjects

From October 2007 until April 2009 hospitalised patients >13 years were included if CAP was diagnosed within 24 hours of admission. CAP was defined as radiological evidence of an infiltrate on chest X-ray and ≥2 of 6 criteria (cough, purulent sputum, temperature >38.50C, abnormal chest auscultation, white blood cell count >10 or <4 ×109/l, positive culture of blood or pleural fluid). Subjects were excluded if they had received parenteral antibiotic before inclusion, had been hospitalised within four weeks of admission, were severely immunocompromised (HIV infection, chemotherapy, neutropenia <1000/uL, steroid treatment >20 mg/day for more than two weeks), had terminal stage of malignancy, or evidence of other causes of abnormalities on the X-ray.

2.3. Data collection

All patients were assessed upon admission, followed up daily during hospitalisation, and on day-30 according to a standardised protocol. Age, gender, cigarette and alcohol use, and clinical presentations were recorded. The admission chest X-rays were assessed by a radiologist in-charge, and later re-assessed to develop standardised X-ray descriptions. Complete blood cell-count, blood chemistry, and blood-gas analysis were performed on admission. Underlying diseases were assessed from clinical, laboratory and radiology data. Severity score was determined using the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI).6 The outcome was assessed as 30-day mortality. Management of patients was left to the discretion of the physicians in charge.

2.4. The microbiological evaluation

Sputum, throat swab, blood, paired sera with a 4-week interval, and urine were sent to the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of Dr. Kariadi Hospital, Semarang. Gram-stained smears were evaluated to assess sputum quality and to help culture interpretation. Ziehl–Neelsen staining was done to screen for acid fast bacilli. Blood was cultured by inoculating four BACTEC bottles [Becton-Dickinson, Rochester, UK] per patient, and sputum samples were inoculated on blood agar, chocolate agar, chocolate agar with gentamicin 5 mg/L, and MacConkey agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). Crystal violet colistin broth (CVCB) and Ashdown agar7 were used for Burkholderia pseudomallei isolation. Bacteria isolated from the initial cultures, sputa, throat swabs, sera, and urine were stored at -80oC, and transported to Rotterdam, for further analyses.

Streptococcus pneumoniae was identified with optochin disk (Oxoid) and, in case of doubt, DNA probe (Accuprobe, San Diego, USA). Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) were identified using the Vitek-2 system (bioMérieux, l’Etoile, France). Acinetobacter baumannii was identified using PCR (bla OXA-51-like).8 Moraxella catarrhalis was confirmed using tributyrin test (Rosco Diagnostics-Taastrup, Denmark). X-V factors (Becton, Dickinson and Company - Sparks, USA) were used for Haemophilus influenzae identification. Slidex Staph Plus latex agglutination (bioMérieux) and Vitek-2 were used for Staphylococcus aureus identification. Ziehl-Neelsen positive sputa were cultured on MGIT media (Becton-Dickinson, Rochester, UK) and confirmed by PCR. Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed with disk diffusions (for S. pneumoniae), Vitek-2 (for S. aureus and GNB), and E-test (for M. catarrhalis). When extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-production was suspected, isolates were further analyzed with cefotaxime-clavulanate or ceftazidime-clavulanate E-test (bioMérieux). Reference strains from ATCC were used as controls and CLSI guidelines were applied.

Serology tests were performed with ELISA for Chlamydia pneumoniae (Medac Diagnostika, Germany), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Virion\Serion, Würzburg, Germany), and Legionella pneumophila (Wampole Laboratories, Princeton, USA). Leptospira serology was performed using microscopic agglutination test (MAT) and ELISA9 in the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Amsterdam, the Netherlands, if the patient had a clinical syndrome compatible with leptospirosis. ELISA for respiratory viruses (Virion\Serion) was performed in the Laboratory of Viroscience, Erasmus MC. Real-time PCRs (RT-PCRs) were done on sputum and on throat swabs for C. pneumoniae and L. pneumophila as described elsewhere.10 RT-PCR for M. pneumoniae, rhinovirus, human corona virus (HcoV) 229E, OC43, and NL63, influenza A and B virus, human metapneumovirus (hMPV), RSV A and B, parainfluenza 1- 4 virus, adenovirus, and bocavirus were performed on throat swabs. Validation of PCR procedures11, 12 and PCR for Leptospira and for Chlamydia psittaci 13, 14 were done as described elsewhere. PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was performed in Erasmus MC. Urinary antigen tests (BinaxNOW, Portland, USA) were performed to detect S. pneumoniae and L. pneumophila serogroup-1 antigen.

2.5. Diagnostic criteria for microbial etiological agents

Sputum cultures were considered positive if sputum quality was good (leukocytes: epithelial-cells ratio was >2.5: 1, leukocyte count was >10/low power field (LPF), epithelial-cell count was <10/LPF), and bacteria growing predominantly on agar were compatible with sputum microscopy. Blood cultures were considered positive if bacteria presented in ≥1 bottle for established pathogens or ≥2 bottles for other species.

Serology was considered positive if there was a four-fold titer increase of any immunoglobulin class. For influenza A and B, since re-infection in one year is unlikely, single sera with positive IgA and negative IgG during the first week of illness were also considered positive. Immunoglobulin classes measured were IgM, IgA, and IgG for C. pneumoniae; total immunoglobulin for L. pneumophila; IgA and IgG for respiratory viruses; IgM and IgG for M. pneumoniae; IgM and total immunogloblin for Leptospira.

RT-PCR were considered positive if the CT value was <50 for M. pneumoniae, ≤35 for Leptospira, and <40 for other pathogens. A positive influenza A PCR was followed with another PCR to distinguish H5N1 from other influenza A viruses. Any visible reaction of the urinary antigen tests was considered positive as instructed by the manufacturer.

For each patient a comprehensive review of the clinical, radiological, and laboratory data was performed by a panel involving a pulmonologist, infectious disease specialists, radiologists, and clinical microbiologists to draw the final conclusions on the etiology of CAP. Etiology was considered established if microbiology test results were compatible with the clinical presentation and radiology.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Chi-Square or Fisher's exact test where appropriate was performed using SPSS 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). The Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test were used to perform survival analysis. P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

2.7. Ethics

The study was approved by The Ethical Committee of Faculty of Medicine Diponegoro University- Dr. Kariadi Hospital (36EC/FK/RSDK/2007). A written informed consent was obtained from each patient or guardian.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

Of the 156 patients enrolled; 135 were hospitalised in Dr. Kariadi hospital and 21 in Semarang Municipal hospital. Eight patients were excluded because of non-confirmed CAP diagnosis (acute respiratory distress syndrome (3 patients), urosepsis (2 patients), no infiltrate on the X-ray on re-assessment (2 patients)), or preceding parenteral antibiotics (1 patient)). Patients’ ages ranged 14–88 years, with 32% aged >60 years. Most patients (52%) had underlying diseases, with 19% having two or more underlying diseases. Severe pneumonia (PSI IV-V) was found in 44% patients. Most (70%) of the chest X-rays showed bronchopneumonia (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with community-acquired pneumonia in Semarang, Indonesia

| Characteristic | Number of Patients (Total N = 148) |

|---|---|

| Age years, median; Inter quartile range (IQR) | 58 (45-69) |

| Male/female | 73 / 75 |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) days | 6 (4-8) |

| 30-day mortality (%) | 44 (30) |

| Underlying diseases (%) | |

| Hypertension | 25 (17) |

| Congestive heart disease | 16 (11) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (10) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 12 (8) |

| Stroke | 27 (18) |

| Asthma | 3 (2) |

| Malignancy | 5 (3) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (3) |

| Pneumonia Severity Index/ PSI (%)* | |

| Class I | 6 (4) |

| Class II | 45 (30) |

| Class III | 32 (22) |

| Class IV | 45 (30) |

| Class V | 20 (14) |

| Chest X-ray (%) | |

| Bronchopneumonia | 103 (70) |

| Alveolar pneumonia | 32 (21) |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 13 (9) |

| Specimens obtained (%) | |

| Sputum, total/good quality** | 103 (70) / 57 (39) |

| Blood culture | 148 (100) |

| Paired sera/single sera | 83 (56) / 64 (43) |

| Throat swabs | 148 (100) |

| Urine | 145 (98) |

according to Fine et al., 19976.

sputum was considered of good quality if the leukocytes: epithelial cells ratio was >2.5, and the leukocyte count was ≥10/LPF and the epithelial cell count <10/LPF.

Only 15% of patients had not received oral antibiotics prior to hospital admission, while 50% were unsure whether they had received antibiotics or not. Thirty eight (26%) patients had a complete set of test specimens (Table 1). No data were missing for underlying diseases, severity, and 30-day mortality.

3.2. Microbiological results

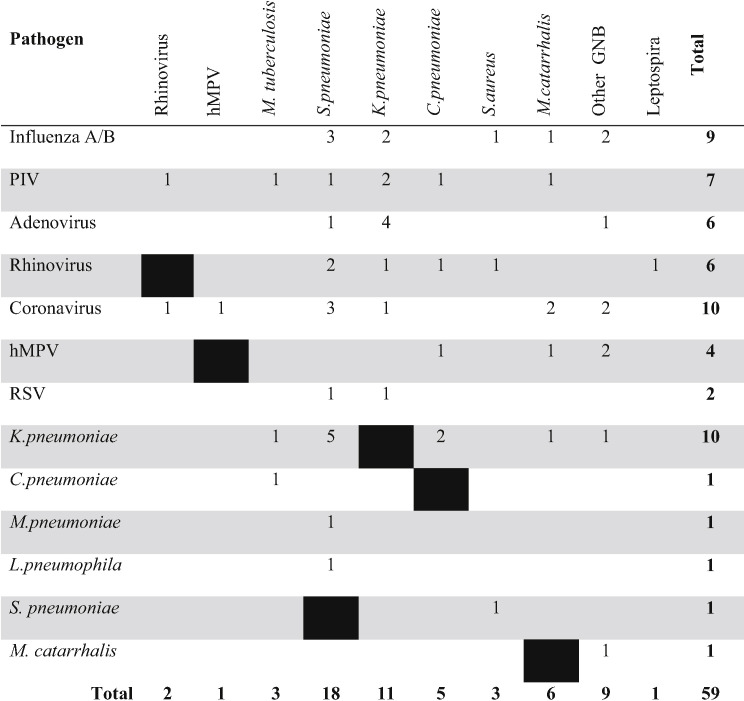

One-hundred and fifty respiratory pathogens were identified from 100 (68%) patients. The microbiological methods by which pathogens were identified are described in Table 2 . Final conclusions regarding the CAP etiology are summarised in Table 3, Table 4 .

Table 2.

Pathogens isolated from laboratory specimens obtained from patients with community-acquired pneumonia in Semarang, Indonesia

| Pathogens | Blood Culture | Sputum Culture | Urinary Antigen Test | Blood and Sputum Culture | Sputum Culture + UAT | Blood and Sputum Culture + UAT | Serology | PCR | Serology + PCR | Culture + PCR | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viruses | |||||||||||

| Influenza A virus | 4 | 10 | 6 | 20 | |||||||

| Influenza B virus | 2 | 4 | 6 | ||||||||

| Rhinovirus | 13 | 13 | |||||||||

| PIV 1-4 | 2 | 9 | 11 | ||||||||

| HcoV OC43 | 8 | 8 | |||||||||

| Adenovirus | 2 | 4 | 6 | ||||||||

| hMPV | 4 | 4 | |||||||||

| RSV | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Total Viruses | 11 | 53 | 6 | 70 | |||||||

| Bacteria | |||||||||||

| S. pneumoniae | 1 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 20 | ||||||

| S. aureus | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||

| K. pneumoniae | 20 | 1 | 21 | ||||||||

| Other GNB | 1 | 6 | 7 | ||||||||

| M. catarrhalis | 5 | 5 | |||||||||

| C. pneumoniae | 8 | 8 | |||||||||

| M. pneumoniae | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| L. pneumophila | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| M. tuberculosis | 1 | 7 | 8 | ||||||||

| Leptospira | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||||||

| Total bacteria | 1 | 36 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 80 |

| Total pathogens | 150 | ||||||||||

UAT = urinary antigen test, PIV = parainfluenza virus, HcoV = human coronavirus, hMPV = human metapneumovirus, RSV = respiratory syncytial virus.

Other GNB = Other Gram-negative bacilli, i.e. E. cloacae, S. maltophilia, A. xylosoxidans, B. cepacia.

Table 3.

Final etiological diagnosis in patients presenting with community-acquired pneumonia in Semarang, Indonesia

| Etiology | Patients (N = 148) Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Single pathogen | 58 (39) |

| virus | |

| Influenza A/B virus | 12 (8) / 5 (3) |

| Rhinovirus | 6 (4) |

| Parainfluenza virus | 5 (3) |

| Adenovirus | 2 (1) |

| Respiratory Syncytial virus | 1 (1) |

| Coronavirus OC43 | 1 (1) |

| human Metapneumovirus | 1 (1) |

| Subtotal | 33 (22) |

| bacteria | |

| K. pneumoniae | 5 (3) |

| S. pneumoniae | 5 (3) |

| M. tuberculosis | 5 (3) |

| Leptospira spp | 4 (3) |

| C. pneumoniae | 2 (1) |

| S. aureus | 2 (1) |

| M. catarrhalis | 1 (1) |

| B. cepacia | 1 (1) |

| Subtotal | 25 (17) |

| More than one pathogen* | |

| Viral infection with superimposed bacterial infection | 24 (16) |

| Tuberculosis with superimposed infection | 3 (2) |

| Other mixed infections | 15 (10) |

| Subtotal | 42 (28) |

| Unknown etiology (no pathogen detected) | 48 (32) |

for further details, see Table 4.

Table 4.

Combinations of respiratory pathogens observed among patients with community-acquired pneumonia

PIV = parainfluenza virus.

Note: 42 patients with multiple infection, of which 35 had two pathogens, 6 had three pathogens (Rhinovirus + S. pneumoniae + S. aureus, Adenovirus + K. pneumoniae + S. pneumoniae, Adenovirus + K. pneumoniae + other GNB*, Coronavirus + K. pneumoniae + M. catarrhalis, RSV type A + K. pneumoniae + S. pneumoniae, Parainfluenza + K. pneumoniae + S. pneumoniae) and one patient had 4 pathogens (Coronavirus + h-Metapneumovirus + K. oxytoca + M. catarrhalis).

A single causative agent was found in 58 (39%) patients, of which 33 (22%) were viruses and 25 (17%) were bacteria. Polymicrobial infection was found in 42 (28%) patients, including viral infections with superimposed bacterial infection, tuberculosis with superimposed secondary infection, and other mixed-infections (multiple viruses, multiple bacteria, and combinations of virus(es) and bacteria) (Table 3).

Seventy viruses were identified in 67 (45%) patients, with influenza A as commonest, identified in 20 (13.5%) patients. PCR detected 16 (80%) cases, while serology detected 10 (50%) cases (Table 2). All influenza A viruses were H3N2. In 12 patients it was the single pathogen found (Table 3); in eight patients other pathogens were also involved (Table 4). Together, influenza A and B viruses caused 26 (18%) cases of CAP in our cohort either as single or as co-pathogen.

The second commonest virus was rhinovirus, which in all 13 (9%) cases were detected by PCR. In six patients this virus was the single pathogen; in seven it was a co-pathogen. Parainfluenza virus was the third commonest virus, detected in 11 (7%) patients, mostly by PCR; five episodes as single pathogen and six as co-pathogen. Other viruses found were HcoV OC43, adenovirus, hMPV, and RSV; most were as co-pathogens, and detected by PCR.

Eighty bacteria were found in 65 (44%) patients, with Klebsiella pneumoniae and S. pneumoniae as the most frequently diagnosed. K. pneumoniae was isolated from 21 (14%) patients; most (95%) from sputum cultures, and 5% from both blood and sputum cultures. S. pneumoniae was diagnosed in 20 (13%) patients, mostly (75%) by urinary antigen tests (Table 2). C. pneumoniae and M. tuberculosis were the third commonest bacterial species identified; each was diagnosed in 5% of patients. Other GNB (Enterobacter cloacae, Klebsiella oxytoca, Achromobacter xylosoxidans, and Burkholderia cepacia) were identified in 7 (5%) patients; most were isolated from sputum cultures. Burkholderia pseudomallei was not found. Blood cultures were positive only in 4 (2%) patients.

Combinations of pathogens in 42 patients are presented in Table 4. Frequent combinations of pathogens were K. pneumoniae + S. pneumoniae (n=5), adenovirus + K. pneumoniae (n=4), and influenza or coronavirus + S. pneumoniae (n=3 each).

The etiology of CAP could not be elucidated in 48 (32%) patients. Pathogen detection was, predictably, related to the availability of diagnostic specimens. Out of 48 cases with unknown etiology, only one patient had complete laboratory specimens from which all tests results were negative. The other 47 had incomplete laboratory specimens; 46 of them had no positive results, and one had so many positive serology results that no conclusion could be drawn. Patients with severe disease (PSI class IV–V) were less likely to receive an etiological diagnosis compared to those with non-severe disease (PSI class I-III, P=0.01).

One isolate of K. pneumoniae was an ESBL-producer, while the others were susceptible to antibiotics except to piperacillin (81% resistant) and nitrofurantoin (76% resistant). Of four regrowable S. pneumoniae, all were susceptible to penicillin, erythromycin, and vancomycin; one was intermediately resistant to co-trimoxazol, and three were resistant to tetracyclin.

3.3. Clinical outcome

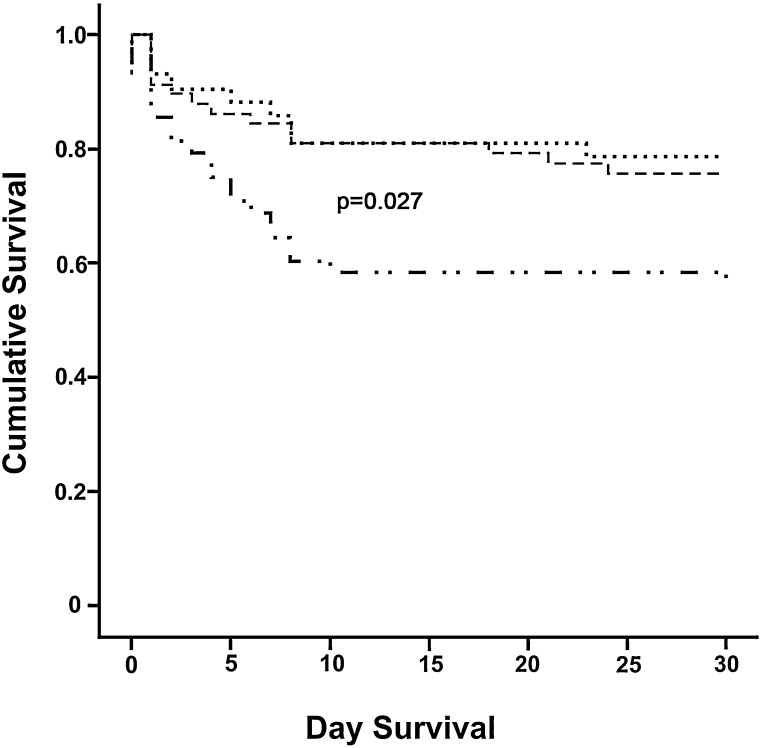

There was no significant difference in underlying diseases, PSI class, length of stay, and mortality among patients with single viral, single bacterial, and mixed viral-bacterial infections (P>0.05). Patients with mixed-viral and mixed-bacterial infections were not analysed due to small numbers. The overall 30-day mortality rate was high (30%) and significantly associated with severity of disease (P<0.001). The mortality rate ranged from 17% in PSI class I patients to 80% in PSI class V patients. Interestingly, survival analysis showed a significantly lower survival rate in CAP patients with unknown etiology (Figure 1 ). Early death (≤48 hours of hospitalization) happened in 18 patients (41% mortality), and was associated with respiratory failure or irreversible septic shock; most of the early deceased patients (14 subjects) had delayed or no access to ICU care because of limited availability of the service. Late death (>48 hours of hospitalization) occurred in 14 patients (32% of mortality), and was associated with worsening conditions from CAP (7 patients) or with their underlying diseases (7 patients). Despite clinical improvement, 12 patients (27% of mortality) died after discharge from hospital for in-home recovery within 30 days of admission. The circumstance of these latter death remained unknown.

Figure 1.

Survival of patients with Community-acquired pneumonia according to diagnostic yield

………. Patients with more than one pathogen

-------- Patients with single pathogen

_. . _. . Patients with no pathogen detected

4. Discussion

This is the first CAP etiology study conducted in Indonesia applying a full range of microbiology tests. Influenza viruses, K. pneumoniae, and S. pneumoniae were the commonest agents of CAP in this region of the world.

Viral infections were surprisingly common, either as single or combined etiology. PCR was instrumental in detecting most respiratory viruses. A recent report from Thailand found viruses in 9% of hospitalised adult CAP patients in Northern Thailand2 and in 25% of adult CAP patients admitted from a pneumonia surveillance in two other provinces.15 Incidence of influenza A infection was 7.4% in hospitalised CAP15 and 7% in severe CAP.5 The use of PCR may, thus, enhance the appropriate use of antimicrobial agents.16 No other CAP studies in Southeast Asia so far have attempted to diagnose viruses.

K. pneumoniae and other GNB were frequently observed in our study, similar to reports from other Southeast Asian countries,2, 3, 17 but different from those from Europe, North America, or Australia.1, 18, 19 The high prevalence of K. pneumoniae and other GNB might, in part, be explained by the common carriage of these bacterial species in the nasopharynx of healthy individuals in the same area.20 The tropical climate with higher temperature and humidity in Semarang may increase the incidence of GNB infection, as those conditions promote the growth and virulence of GNB.21, 22

S. pneumoniae infection was detected in only 13% of the patients, mostly by urinary antigen tests. Cultures frequently failed to grow this species, possibly due to the common use of antibiotics in the community, underlining the importance of alternative methods to detect pneumococci, as by PCR3 or urinary antigen test.23 However, a positive finding with the latter test should be interpreted carefully particularly in patients with COPD.23 Previous studies in Southeast Asia reported various numbers for the relative contribution of S. pneumoniae, from 2%17 through 52%24 depending on the study population and the laboratory methods, while studies from Europe, North America, and Australia consistently reported it as the most common cause of CAP.1, 18, 19

Aside from the climate, the differences between the CAP etiology reported in our study and that in previous reports might also relate to differences in patients age, underlying diseases, and radiological type of pneumonia. Our patients were relatively young, had more often cerebrovascular underlying diseases, and had often bronchopneumonia instead of lobar or alveolar pneumonia. The wide spread use of influenza vaccination in other parts of the world may help explain the differences in the incidence of influenza in CAP. Taken together, these differences imply that a guideline of CAP management construed and implemented in Europe, North America, and Australia might not be directly applicable in Indonesia.

Most CAP studies distinguished definite from probable etiology based on microbiology results. We did not use this distinction, instead, we interpreted microbiological, clinical and radiological findings in a multidisciplinary discussion to make a final diagnosis, since in our opinion, clinical data cannot be omitted in doing so.

Extending the range of laboratory diagnostics applied to include viral as well as bacterial and fungal pathogen will, predictably increase the number of pathogens detected, and, thereby, increase the chance of finding polymicrobial infections.4, 25 We found mixed infection in a sizable proportion of the cohort of patients included in the study. Some of these mixed infections are common, e.g. viral infection with superimposed bacterial infection26 and tuberculosis with superimposed infection. Other mixed infections, e.g. by multiple bacteria or multiple viruses, are more difficult to understand and pose the problem of discriminating between infection and carriage.

Most bacteria causing CAP in our study were susceptible to early generation antibiotics. These findings are consistent with other observation from Indonesia.27, 28 Hence, the choice of antibiotics for the initial empirical treatment of CAP should not include the later generation of antibiotics, including a third generation cephalosporin which is recommended by the local guideline.29 A more appropriate choice to consider would be amoxicillin-clavulanic acid or ampicillin-sulbactam.

The crude mortality rate was high, and related to severity of the disease. However, even in low risk patients, the mortality in our study was still quite high, not only compared to that in North-America and Europe, but also to other studies from Southeast Asian countries.2, 5 The high mortality observed in our study suggests problems in the patient care process, which needs further analysis. Determinants of poor outcome may at least in part, include delay in presenting to the hospital, inappropriate initial treatment, limited access to mechanical ventilators, inappropriate antibiotic therapy, underlying diseases, and the severity of the disease on admission (to be published elsewhere). Interestingly, mortality was significantly higher among patients with unknown etiology. This finding may be explained by limitations in acquiring appropriate laboratory samples due to the severity of the disease at the time the patients were admitted. This is rather unfortunate, since these patients are those who need most to be managed based on an established etiology. This finding implies the need to perform all diagnostic procedures early, without delay, especially in patients with severe disease, so that the etiology of CAP in this group is established early, at a time its management can still be optimised.

Since this study was performed in one urban area in Indonesia, involving only two hospitals, our findings might not be representative for the whole of Indonesia. A similar, multicenter study of the etiology of CAP in Indonesia would be needed to confirm the peculiar spectrum of etiology of CAP in Indonesia suggested by this study.

5. Conclusions

Multicenter CAP studies which include viral etiologies, should be carried out in Indonesia and other countries in this region to delineate the full spectrum of etiological agents in CAP patients and to generate local guidelines for the management of CAP.

Bacteria causing CAP in this area of the world continue to present wild type antibiotic susceptibility profiles so that early generation antibiotics can be used as initial empiric treatment, thereby avoiding the expense and selection pressure exerted by newer generations of antibiotics, especially third generation cephalosporins and carbapenems. The frequent incidence of GNB infection requires initial therapy to cover GNB in addition to the Pneumococcus. Rapid bacteriological diagnostics are required to be able to adapt initial therapy, including alternative tests for detecting S. pneumoniae. Performing diagnostic procedures early, without delay, should be prioritized since establishing an etiological diagnosis is likely to improve clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Bambang Isbandrio (Department of Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine Diponegoro University/Dr. Kariadi Hospital), Roy Hardjalukita (Department of Internal Medicine, Semarang Municipal Hospital), Matthias F.C. Beersma and Gerard J.J. van Doornum (Department of Viroscience Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands), Edou R. Heddema (Orbis Medisch Centrum, Sittard-Geleen, the Netherlands), Marga G.A. Goris and Ahmed A.A. Ahmed (KIT (Royal Tropical Institute), Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Peter W.M. Hermans (Nijmegen Institute for Infection, Inflammation, and Immunity (N4i), and Laboratory of Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands), Stephanie Natsch (Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands), Residents of Department of Internal Medicine and Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine Diponegoro University, microbiology technicians from Dr. Kariadi Hospital and Erasmus MC, and virology technicians from Erasmus MC, for kind help and support of this study.

Funding: The study was funded by the Royal Netherlands Academy for Arts and Sciences (KNAW) – Science Program Indonesia-the Netherlands (SPIN) through the KNAW Postdoc Programme no. 06-PD-17, and by the Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and the Department of Viroscience, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam. HF received a scholarship from the Ministry of National Edication and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia. MHG received postdoctoral grant from KNAW, the Netherlands.

Potential conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflict of interest

Corresponding Editor: Eskild Petersen, Aarhus, Denmark

References

- 1.Charles P.G.P., Whitby M., Fuller A.J., Stirling R., Wright A.A., Korman T.M. The etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in Australia: Why penicillin plus doxycycline or a macrolide is the most appropriate therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1513–1521. doi: 10.1086/586749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hara K., Yahara K., Gotoh K., Nakazono Y., Kashiwagi T., Imamura Y. Clinical study concerning the relationship between community-acquired pneumonia and viral infection in northern Thailand. Intern Med. 2011;50:991–998. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mustafa M.I.A., Al-Marzooq F., How S.H., Kuan Y.C., Ng T.H. The use of multiplex real-time PCR improves the detection of the bacterial etiology of community acquired pneumonia. Tropical Biomedicine. 2011;28:531–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song J.-H., Oh W.S., Kang C.-I., Chung D.R., Peck K.R., Ko K.S. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of community-acquired pneumonia in adult patients in Asian countries: a prospective study by the Asian network for surveillance of resistant pathogens. Intl J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apisarnthanarak A., Puthavathana P., Mundy L.M. Risk factors and outcomes of influenza A (H3N2) pneumonia in an area where avian influenza (H5N1) is endemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:479–482. doi: 10.1086/513724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fine M.J., Auble T.E., Yealy D.M., Hanusa B.H., Weissfeld L.A., Singer D.E. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl JMed. 1997;336:243–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashdown L., Clark S. Evaluation of culture techniques for isolation of Pseudomonas pseudomallei from soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992:4011–4015. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.4011-4015.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turton J.F., Woodford N., Glover J., Yarde S., Kaufmann M.E., Pitt T.L. Identification of Acinetobacter baumannii by detection of the bla OXA-51-like carbapenemase gene intrinsic to this species. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2974–2976. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01021-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goris M.G.A., Leeflang M.M.G., Boer K.R., Goeijenbier M., Gorp ECMv, Wagenaar J.F.P. Establishment of valid laboratory case definition for human leptospirosis. Bacteriol Parasitol. 2012:3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Templeton K.E., Scheltinga S.A., Eeden WCJFMvd, Graffelman A.W., van den Broek P.J., Claas E.C.J. Improved diagnosis of the etiology of community-acquired pneumonia with real-time polymerase chain reaction. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:345–351. doi: 10.1086/431588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stadhouders R., Pas S.D., Anber J., Voermans J., Ted H.M. Mes, Schutten M. The effect of primer-template mismatches on the detection and quantification of nucleic acids using the 5′ nuclease assay. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12:109–117. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoek R.A.S., Paats M.S., Pas S.D., Bakker M., Hoogsteden H.C., Boucher C.A.B. Incidence of viral respiratory pathogens causing exacerbations in adult cystic fibrosis patients. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;45:65–69. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.708942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed A.A., Engelberts M.F.M., Boer K.R., Ahmed N., Hartskeerl R. Development and validation of a real-time PCR for detection of pathogenic Leptospira species in clinical materials. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heddema E.R., Hannen EJv, Duim B., Jongh BMd, Kaan J.A., Kessel Rv An outbreak of psittacosis due to Chlamydophila psittaci genotype A in a veterinary teaching hospital. J Med Microbiol. 2006:55. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46692-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen S.J., Thamthitiwat S., Chantra S., Chittaganpitch M., Fry A.M., Simmerman J.M. Incidence of respiratory pathogens in persons hospitalized with pneumonia in two provinces in Thailand. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1811–1822. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaydos C.A. What is the role of newer molecular tests in the management of CAP? Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27:49–69. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdullah S., Darus Z., Hashim C.W.A. The outcome of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia in Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia. Intl Med J. 2011;18:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reissig A., Mempel C., Schumacher U., Copetti R., Gross F., Aliberti S. Microbiological diagnosis and antibiotic therapy in patients with community-acquired pneumonia and acute COPD exacerbation in daily clinical practice: Comparison to current guidelines. Lung. 2013:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9460-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, Fakhran S, Balk R, Trabue C, Bramley AM, Anderson EJ, Courtney M, Ampofo K, Arnold SR, Williams DJ, Erdman D, Winchell JM, Carvalho MdG, Lindstrom S, Chappell JD, Qi C, Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, Schneider E, Hicks LA, McCullers JA. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia among hospitalized adults in the United States: Preliminary data from the CDC etiology of pneumonia in the community (EPIC) study.ID Week 2012, San Diego, CA; 2012.

- 20.Farida H., Severin J.A., Gasem M.H., Keuter M., Broek Pvd, Hermans P.W.M. Nasopharyngeal carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Gram-negative bacilli in pneumonia-prone age groups in Semarang, Indonesia. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:1614–1616. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00589-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eber M.R., Shardell M., Schweizer M.L., Laxminarayan R., Perencevich E.N. Seasonal and temperature-associated increases in Gram-negative bacterial bloodstream infections among hospitalized patients. PloS one. 2011;6:e25298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raetz C.R.H., Reynolds C.M., Trent M.S., Bishop R.E. Lipid a modification systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:295–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzeng D.H., Lee Y.L., Lin Y.H., Tsai C.A., Shi Z.Y. Diagnostic value of the Binax NOW assay for identifying a pneumococcal etiology in patients with respiratory tract infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2006;39:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reechaipichitkul W., Lulitanond V., Sawanyawisuth K., Lulitanond A., Limpawattana P. Etiologies and treatment outcomes for out-patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) at Srinagarind Hospital, Khon Kaen, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36:1261–1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansson N., Kalin M., Annika T.L., Giske C.G., Hedlund J. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia: Increased microbiological yield with new diagnostic methods. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:202–209. doi: 10.1086/648678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavia A.T. What is the role of respiratory viruses in community-acquired pneumonia? What is the best therapy for influenza and other viral causes of community-acquired pneumonia? Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27:157–175. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lestari E.S., Severin J.A., Filius P.M.G., Kuntaman K., Duerink D.O., Hadi U. Antimicrobial resistance among commensal isolates of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus in the Indonesian population inside and outside hospitals. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0396-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Severin J.A., Lestari E.S., Kloezen W., Toom NL-d, Mertaniasih N.M., Kuntaman K. Faecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among humans in Java, Indonesia, in 2001–2002. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:455–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perhimpunan Dokter Paru Indonesia. Pneumonia komuniti: Pedoman diagnosis & penatalaksanaan di Indonesia. Jakarta; 2003.