Highlights

-

•

Feline vesivirus RNA was detected and sequenced in seven samples from diarrheic cats.

-

•

One sample was characterized as a feline norovirus (FeNoV) by phylogenetic analysis.

-

•

Norovirus genogroup IV (GIV) detection and quantification was performed using quantitative one step RT-PCR.

-

•

FeNoV GIV was detected at 5.98 × 105 genome copies per gram of stool sample.

-

•

This is the first report of enteric feline calicivirus (FCV) and FeNoV in diarrheic cats in South America.

Keywords: Calicivirus, Norovirus, Cat, Sequence analysis, Real-time PCR

Abstract

Feline caliciviruses (FCVs) have occasionally been described in cats in association with enteric disease, but an etiological role for these viruses in acute gastroenteritis is still unclear. In this study, molecular characterization of FCV and feline norovirus (FNoV) was undertaken using real-time PCR (RT-PCR) and sequence analysis of the ORF1 region in fecal specimens from 29 diarrheic cats. The specimens were also screened for parvovirus, coronavirus, astrovirus and group A rotavirus. A quantitative one step RT-PCR was also performed to detect and quantitate NoV genogroup IV and the role of these animal caliciviruses in feline gastroenteritis was investigated. This is the first description of enteric FCV and FNoV in South America.

The Caliciviridae family consists of five well-defined genera: Norovirus (NoV), Sapovirus, Lagovirus, Nebovirus, and Vesivirus. Only Sapovirus and Norovirus are known to infect humans and most of the calicivirus isolates detected in dogs and cats belong to the genus Vesivirus (Radford et al., 2007).

Feline calicivirus (FCV) is a common pathogen of domestic cats. The virus is associated with a variety of clinical presentations, from subclinical infections to upper respiratory disease and/or signs of oral ulceration, acute and chronic stomatitis, acute arthritis, febrile limping syndrome and hemorrhagic-like fever, also known as FCV-associated virulent systemic disease (FCV-VSD). Some FCV strains have the ability to actively replicate in the enteric tract and have been occasionally detected in fecal specimens of cats (Radford et al., 2007). Recently, NoV strains have been identified in the feces of cats in the USA and Japan, but their role as enteric pathogens has not been elucidated (Pinto et al, 2012, Soma et al, 2015).

From December 2010 to June 2012, a total of 29 diarrheic fecal specimens from kittens up to 10 months of age were collected from four rescue shelters in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The kittens were housed with adult dogs and cats of different origins. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Animal Research (PROPP/ UFF-CEPA/ NAL, Protocol 0223/12).

For FCV detection, nucleic acids were extracted from 10% fecal suspensions in 0.01 M Tris/HCl/Ca2+ using the PureLink Spin column-based kit (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed on extracted RNA using random primers (Invitrogen) and the Superscript III enzyme (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Initially, all 29 specimens were screened with primers p289H, position 4663–4684 (TGACGATTTCATCATCACCATA)/p290H, position 4354–4376 (GATTACTCCAGGTGGGACTCCAC), targeting a 300 nt fragment of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) region at the 3′ end of ORF-1b (Farkas et al., 2004). For detection of NoV RNA, all specimens were screened by one step real-time PCR (RT-PCR) with primers FNoV-F9, position 4655–4677 (GCCCACTGGATWTACACCCTCTC) and FNoV-R15, position 4970–4993 (CTGATGGTTGGGTCCTCTGGTCCA), targeting a 550 nt fragment of the 3′ end of the NoV GIV RdRp encoding region (Pinto et al., 2012).

The 29 specimens were also submitted for NoV GIV detection and quantification with a TaqMan-based approach, using the RNA UltraSense one-step quantitative RT-PCR system (Life Technologies). The primers and probe targeted a highly conserved region of the open reading frame (ORF1–ORF2) junction of the genome with primer pair Mon 4F, position 718–743 (TTTGAGTCYATGTACAAGTGGATGC) Mon 4R, position 815-794 (TCGACGCCATCTTCATTCACA) and probe Ring 4, position 763 (FAM-TGGGAGGGGGATCGCGATCT-BHQ; Trujillo et al., 2006). A 10-fold serial dilution of plasmid DNA containing the target NoV GIV sequence was used to generate a standard curve between the logarithm of the standard concentrations (106–101 copies per reaction) and the cycle threshold (Ct) value for virus quantification. Amplification data were collected and analyzed using commercially available software (Applied Biosystems 7500 Software v2.0).

Modeltest software 3.7 was used to test for the statistically justified model of DNA substitution that best fit our data set. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using a matrix of genetic distances established under the Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano plus I model (MEGA 6.0 suite). Additionally, specimens were screened for the presence of feline parvovirus (FPV), feline coronavirus (FCoV), feline astrovirus and group A rotavirus, either by PCR or RT-PCR (Buonavoglia et al, 2001, Pratelli et al, 2001, Chu et al, 2008, Gómez et al, 2011 Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Feline caliciviruses (feline enteric calicivirus and feline norovirus) and other virus associated with gastroenteritis (feline parvovirus, feline coronavirus, rotavirus group A) identified by PCR and RT-PCR in feral cats with diarrhea.

| Viruses | Positive specimens n (%) |

|---|---|

| FPV | 5 (17.2%) |

| FCoV | 1 (3.4%) |

| FCV | 7 (24%) |

| RV-A | 1 (3.4%) |

| FeAst | 2 (6.8%) |

| FCV/FPV | 3 (10.3%) |

| FCV/FCoV | 1 (3.4%) |

| FPV/FeAstV | 1 (3.4%) |

| FNoV/FCoV/FPV | 1 (3.4%) |

FPV, feline parvovirus; FCoV, feline coronavirus; RV-A, group A rotavirus; FCV, feline calicivirus; FNoV, feline norovirus; FeAst, feline astrovirus.

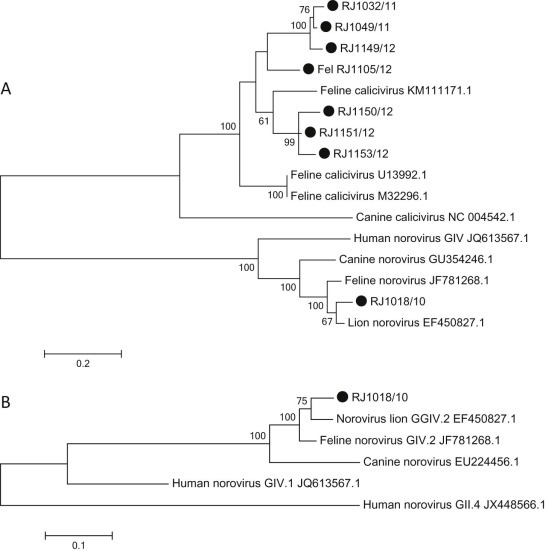

FCV RNA was detected in 8/29 (27.6%) specimens. Based on nucleotide (nt) analysis of the RdRp gene, seven FCV sequences shared 60.9–80.2% nt identity with sequences from the Vesivirus genus, as compared to the feline (42.7–45.6% nt identity) and human NoVs (45.1–49.5% nt identity). The Brazilian viruses clustered together with FCV (Fig. 1A ).

Fig. 1.

(A) Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano plus I phylogenetic tree based on a 300 bp region of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase region of feline coronavirus (FCV) strains (300 bp). Brazilian FCV sequences (GenBank accession number KM505126- KM505132) and the Brazilian feline norovirus sequences (GenBank accession number KM505133) are shown as filled circles. (B) Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano plus I phylogenetic tree based on the partial gene sequence (550 bp) of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of norovirus strains. The Brazilian feline norovirus sequence is highlighted (GenBank accession number KM505133). Bootstrap values based on 2000 generated trees are displayed at the nodes (values > 50% are shown). The branch lengths are proportional to the evolutionary distance between sequences and the distance scale in nucleotide substitutions per position is shown.

Surprisingly, an analysis comparing the sequence of RJ1018/10 with sequences available in the GenBank database, using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST),1 indicated that the 300-base pair (bp) fragment displayed 91.3% nt identity with feline NoV (FNoV; strain CU081210E, accession number JF781268; Fig. 1A). This specimen (RJ1018/10) tested positive using a specific primer pair for NoV GIV RdRp (RJ1018/10). Nucleotide analysis of the 550-bp fragment showed that the NoV GIV strain was closely related to other cat, dog and lion GIV NoV strains (93.2–93.9% nt identity; Fig. 1B). Using the qPCR, NoV GIV RNA was detected in the same specimen (RJ1018/10) at a cycle threshold of 31.8, corresponding to 5.98 × 105 genome copies/g feces.

Single calicivirus infections were detected in five cats and mixed infections in another three cats. There was one cat with FCV/FCoV and one cat with FNoV/FCoV/ FPV (RJ1018/10) (Table 1).

Few studies have investigated FCV-associated outbreaks of gastroenteritis in cats (Pinto et al., 2012). In this study, we detected only FCV infection, using RT-PCR in six of seven kittens with clinical evidence of gastroenteritis.

Descriptions of NoV GIV infections in pets have recently been reported. Canine NoVs were described for the first time in 2008 in Italy (Martella et al., 2008). FNoV GIV was first described in the USA in 2010, and around that time it was also detected in other carnivores (lions and dogs), suggesting interspecies circulation of NoV GIV (Pinto et al., 2012).

This study was conducted to identify the viral agents associated with diarrhea in cats and there was no attempt to determine the primary etiology of the diarrhea. We report here for the first time the detection of caliciviruses (FCV and FNoV) in diarrhea in domestic cats in South America. The FNoV reported in this study is phylogenetically similar to human GIV.1 NoVs. Further studies should be conducted in domestic animals to determine the prevalence of FNoV and to monitor the circulation of these viruses and their impact on feline populations. Our results indicate that cats with acute gastroenteritis should be screened for FCV as well as established pathogens such as FPV and FCoV.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors of this paper has a financial or personal relationship with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper.

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by the Carlos Chagas Filho Foundation for Research Support of the State of Rio de Janeiro (grant number E-26/110.909/2013), the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (grant number 023/2011), the Fluminense Federal University Office of Research and Graduate Studies, and the Oswaldo Cruz Institute.

Footnotes

See: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed 19 June 2015).

References

- Buonavoglia C., Martella V., Pratelli A., Tempesta M., Cavalli A., Greco G., Buonavoglia D. Evidence for evolution of canine parvovirus type 2 in Italy. Journal of General Virology. 2001;82:3021–3025. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-12-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D.K.W., Poon L.L.M., Guan Y., Peiris J.S.M. Novel astroviruses in insectivorous bats. Journal of Virology. 2008;82:9107–9114. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00857-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas T., Zong W.M., Jing Y., Huang P.W., Espinoza S.M., Martinez N. Genetic diversity among sapoviruses. Archives of Virology. 2004;149:1309–1323. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez M., Mendonca M., Volotão E.M., Tort L.F., Silva M.F.M., Cristina J., Leite J.P.G. Rotavirus A genotype P[4]G2: Genetic diversity and reassortment events among strains circulating in Brazil between 2005 and 2009. Journal of Medical Virology. 2011;83:1093–1106. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martella V.E., Lorusso N., Decaro G., Elia A., Radogna M., D'Abramo C., Desario A., Cavalli M., Corrente M., Camero C.A. Detection and molecular characterization of a canine norovirus. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2008;14:1306–1308. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.080062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto P., Wang Q., Chen N., Dubovi E.J., Daniels J.B., Millward L.M., Buonavoglia C., Martella V., Saif L.J. Discovery and genomic characterization of noroviruses from a gastroenteritis outbreak in domestic cats in the US. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratelli A., Buonavoglia D., Martella V., Tempesta M., Lavazza A., Bounavoglia C. Diagnosis of canine coronavirus infection using nested-PCR. Journal of Virological Methods. 2001;84:91–94. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(99)00134-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford A.D., Coyne K.P., Dawson S., Porter C.J., Gaskell R.M. Feline calicivirus. Veterinary Research. 2007;38:319–335. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soma T., Nakagomi O., Nakagomi T., Mochizuki M. Detection of Norovirus and Sapovirus from diarrheic dogs and cats in Japan. Microbiology and Immunology. 2015;59:123–128. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo A.A., McCaustland K.A., Zheng D.P., Hadley L.A., Vaughn G., Adams S.M., Ando T., Glass R.I., Monroe S.S. Use of TaqMan real-time reverse transcription-PCR for rapid detection, quantification, and typing of norovirus. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44:1405–1412. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1405-1412.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]