Abstract

The aim of this study was to quantify and compare interferon-γ (IFN-γ) concentrations in the serum of clinically normal cats infected with feline coronavirus (FCoV) with its concentration in the sera and effusions of cats with feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), a disease associated with infection with a mutated form of FCoV.

Clinically normal FCoV-infected cats living in catteries with a high prevalence of FIP had the highest serum IFN-γ concentrations. The serum concentration of IFN-γ was not significantly different in cats with FIP compared with clinically normal FCoV-infected animals living in catteries with a low prevalence of the disease. Moreover, the concentration of IFN-γ was significantly higher in the effusions than in the serum of cats with FIP, probably due to IFN-γ production within lesions. These findings support the hypothesis that there is a strong, ‘systemic’ cell mediated immune response in clinically normal, FCoV-infected cats and that a similar process, albeit at a tissue level, is involved in the pathogenesis of FIP.

Keywords: Feline coronavirus (FCoV), Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), Interferon-γ (IFN-γ), ELISA, Cell mediated immunity

Both the humoral and cellular components of the feline immune system influence the development of feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), the disease caused by a mutated form of feline coronavirus (FCoV). Humoral immunity is thought to contribute to the development of effusions within body cavities, while cats with strong cell mediated immunity (CMI) either do not become infected with FCoV or develop the non-effusive form of FIP (Pedersen, 1987).

The cytokine interferon-γ (IFN-γ) is an important modulator of CMI. The expression of IFN-γ mRNA by leucocytes in the circulation or in tissues has been investigated in many studies using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and immunohistochemistry, respectively (Gunn-Moore et al., 1998, Dean et al., 2003, Kiss et al., 2004, Berg et al., 2005, Gelain et al., 2006). A recent study in our laboratory (Gelain et al., 2006) and previous studies (Gunn-Moore et al., 1998, Kiss et al., 2004) found high IFN-γ mRNA expression in the peripheral blood leucocytes (PBLs) of clinically normal cats with FCoV infection, but low expression in cats with FIP. In contrast, IFN-γ mRNA is abundant within FIP lesions (Berg et al., 2005).

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the patterns of IFN-γ production in the earlier experimental studies were replicated in cats naturally infected with FCoV and with naturally occurring FIP. We analysed 79 sera and 48 effusions collected from 101 cats during a 5 year period (2000–2005).

The cats were divided into two basic groups: animals with clinical FIP (group A, n = 81) and FCoV-infected, clinically normal animals (group B, n = 20). Group A was further divided into two subgroups: cats with non-effusive FIP (subgroup A1, n = 9) and cats with effusive FIP (subgroup A2, n = 72). From subgroup A2, samples of both sera and effusion were available from 26 cats in addition to samples of effusions only from a further 22 animals and serum samples only from 24 cats. Group B was further divided into subgroups B1 (consisting of 13 animals from catteries with a high prevalence of FIP of >2 cases/year) and B2 (consisting of seven animals from catteries with a low prevalence of FIP of one case in the past 5 years).

The clinical diagnosis of FIP in the group A cats was confirmed at necropsy following histopathological and immunohistochemical examination in the case of 59 animals and in the case of 22 cats by immunofluorescence on cytocentrifuged effusions (Paltrinieri et al., 1999). Group B cats were clinically normal and did not exhibit haematological or blood biochemical evidence of FIP. All cats in this group remain clinically normal some 3–5 years later. These cats were classified as infected with FCoV based on repeated serological screening or on the detection of the virus by PCR in the faeces or on both of these detection methods. These examinations revealed high FCoV antibody titres of between 1:200 and 1:1600 and the frequent shedding of FCoV by subgroup B1 cats and persistently low FCoV antibody titres of <1:200 and occasional faecal shedding in subgroup B2 animals.

Serum IFN-γ concentration was determined using a specific ELISA for feline IFN-γ (R&D Systems). The within- and between-run variability of the test was 7.4 ± 6.3% and 8.9 ± 6.1%, respectively.

Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistica software (Statsoft Inc.). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare data from groups A and B and from subgroups B1 and B2. A Wilcoxon paired test was used to compare serum and effusion IFN-γ levels in the same cat.

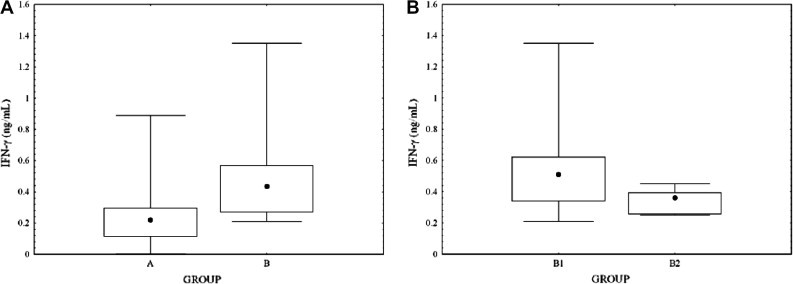

The serum concentration of IFN-γ (ng/mL) was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in group B (0.51 ± 0.32) than in group A (0.25 ± 0.18) animals (Fig. 1 A). Subgroup B1 cats had significantly higher (P < 0.05) IFN-γ concentrations (0.60 ± 0.36) than did those in subgroup B2 (0.34 ± 0.08) (Fig. 1B). No significant difference in serum IFN-γ concentration was found between cats with effusive (0.24 ± 0.17) and non-effusive FIP (0.29 ± 0.24). The concentration of IFN-γ was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in the effusion (11.29 ± 19.95) than in the serum (0.26 ± 0.18) of cats with FIP.

Fig. 1.

(A) Serum concentration of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in cats with FIP (group A) and in FCoV-infected, clinically normal animals (group B). (B) Serum concentration of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in cats living in catteries with a high (group B1) and low (group B2) prevalence of FIP. Boxes indicate I–III interquartile intervals. Horizontal bars indicate minimum and maximum values. Black dots represent the median value for each group.

To the authors’ knowledge, normal reference values for feline serum IFN-γ concentrations are not available to allow comparisons with the data generated in this study. However, although not strictly controls, subgroup B2 cats could be considered ‘controls’ for comparative purposes in the context of this study, as although FCoV-infected, as are the majority of cats from multi-cat households (Pedersen, 1995), these animals were clinically and haematologically normal.

The serum IFN-γ concentration of cats with FIP (group A) was not significantly different from that of subgroup B2 cats, while subgroup B1 cats had significantly higher median serum concentrations. Frequent FCoV cross-infection and FCoV mutation are likely in catteries with a high prevalence of FIP. Although the time of such ‘field’ infection cannot be determined precisely, cats such as those in subgroup B1 are thought to experience continuous re-infection according to the infection model proposed by Foley et al. (1997). Cats from such catteries are likely to be resistant to developing FIP. In the present study, subgroup B1 cats did not have evidence of FIP, and their higher serum IFN-γ concentrations compared with subgroup B2 animals may be linked to their continuous re-infection with FCoV. Increased expression of this cytokine by PBLs (Gunn-Moore et al., 1998, Kiss et al., 2004) or increased numbers of IFN-γ-producing lymphocytes in blood and lymph nodes, as reported in cats living in FCoV-endemic catteries may explain the higher serum IFN-γ concentrations in this group (Kipar et al., 2001, Paltrinieri et al., 2003, De Groot-Mijnes et al., 2005).

In contrast, the fact that cats with FIP do not have increased serum IFN-γ concentrations suggests low IFN-γ expression by PBLs (Gelain et al., 2006) or depleted numbers of lymphocytes in the blood or lymph nodes (Kipar et al., 2001, Paltrinieri et al., 2003, De Groot-Mijnes et al., 2005). Although the authors were unable to find published data concerning IFN-γ levels in the effusions of cats with which to compare, IFN-γ concentrations in the effusions of cats with FIP were 40-fold higher than the serum concentrations of this cytokine in the same animals. This suggests that the IFN-γ present in the effusions is produced by cells within FIP lesions, as reported by Berg et al. (2005).

The results suggest that although cats resistant to FCoV infection have strong CMI as measured by serum IFN-γ production, CMI is also likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of FIP, albeit at a tissue level, as evidenced by the high IFN-γ concentration of the FIP effusions. These findings may form the basis of further studies into the mechanisms through which IFN-γ production prevents the onset of FIP in some instances and potentially contributes to the development of this disease in others.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors of this paper has a financial or personal relationship with other people or organisations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper.

Acknowledgements

This study was co-funded by Grants from The Italian Government (PRIN2005) and from The University of Milan (FIRST 2006). The authors are grateful to Drs. Maria Elena Gelain and Serena Tagliabue for technical support.

References

- Berg A.-L., Ekman K., Bela´k S., Berg M. Cellular composition and interferon-γ expression of the local inflammatory response in feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) Veterinary Microbiology. 2005;111:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot-Mijnes J.D.F., Van Dun J.M., Van Der Most R.G., De Groot R.J. Natural history of a recurrent feline coronavirus infection and the role of cellular immunity in survival and disease. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:1036–1044. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1036-1044.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean G.A., Olivry T., Stanton C., Pedersen N.C. In vivo cytokine response to experimental feline infectious peritonitis virus infection. Veterinary Microbiology. 2003;97:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley J.E., Poland A., Carlson J., Pedersen N.C. Patterns of feline coronavirus infection and fecal shedding from cats in multiple cat environments. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1997;210:1307–1312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelain M.E., Meli M., Paltrinieri S. Whole blood cytokine profiles in cats infected by feline coronavirus and healthy non-FCoV infected specific pathogen-free cats. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2006;8:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn-Moore D.A., Caney S.M.A., Gruffydd-Jones T.J., Helps C.R., Harbour D.A. Antibody and cytokine responses in kittens during the development of feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 1998;65:221–242. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(98)00156-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipar A., Kohler K., Leukert W., Reinacher M. A comparison of lymphatic tissues from cats with spontaneous feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), cats with FIP virus infection but no FIP, and cats with no infection. Journal of Comparative Pathology. 2001;125:182–191. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2001.0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss I., Poland A.M., Pedersen N.C. Disease outcome and cytokine responses in cats immunized with an avirulent feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV)-UCD1 and challenge-exposed with virulent FIPV-UCD8. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2004;6:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paltrinieri S., Parodi M. Cammarata, Cammarata G. In vivo diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis by comparison of protein content, cytology and direct immunofluorescence test performed on peritoneal and pleural effusions. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 1999;11:358–361. doi: 10.1177/104063879901100411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paltrinieri S., Ponti W., Comazzi S., Giordano A., Poli G. Shifts in circulating lymphocyte subsets in cats with feline infectious peritonitis (FIP): pathogenic role and diagnostic relevance. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2003;96:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(03)00156-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C. Virologic and immunologic aspects of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1987;218:529–550. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-1280-2_69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C. An overview of feline enteric coronavirus and infectious peritonitis virus infections. Feline Practice. 1995;23:7–20. [Google Scholar]