Abstract

Background

The Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was first described in 2012 and attracted a great international attention due to multiple healthcare associated outbreaks. The disease carries a high case fatality rate of 34.5%, and there is no internationally or nationally recommended therapy.

Method

We searched MEDLINE, Science Direct, Embase and Scopus databases for relevant papers published till March 2019 describing in vitro, in vivo or human therapy of MERS.

Results

Initial search identified 62 articles: 52 articles were from Medline, 6 from Embase, and 4 from Science Direct. Based on the inclusions and exclusions criteria, 30 articles were included in the final review and comprised: 22 in vitro studies, 8 studies utilizing animal models, 13 studies in humans, and one study included both in vitro and animal model. There are a few promising therapeutic agents on the horizon. The combination of lopinavir/ritonavir and interferon-beta- 1b showed excellent results in common marmosets and currently is in a randomized control trial. Ribavirin and interferon were the most widely used combination and experience comes from a number of observational studies. Although, the data are heterogenous, this combination might be of potential benefit and deserve further investigation. There were no randomized clinical trials to recommend specific therapy for the treatment of MERS-CoV infection. Only one such study is planned for randomization and is pending completion. The study is based on a combination of lopinavir/ritonavir and interferon-beta- 1b. A fully human polyclonal IgG antibody (SAB-301) was safe and well tolerated in healthy individuals and this agent may deserve further testing for efficacy.

Conclusion

Despite multiple studies in humans there is no consensus on the optimal therapy for MERS-CoV. Randomized clinical trials are needed and potential therapies should be evaluated only in such clinical trials. In order to further enhance the therapeutic aroma for MERS-CoV infection, repurposing old drugs against MERS-CoV is an interesting strategy and deserves further consideration and use in clinical settings.

Keywords: MERS, Therapy, Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus

1. Introduction

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was first identified in 2012 and since then the disease has attracted an increasing international interest to resolve issues related to the epidemiology, clinical features, and therapy. This interest is further enhanced by the fact that MERS-CoV infection resulted in 2428 cases in 27 countries around the world as of June 23, 2019 [1] and most of the cases are linked to the Middle East [2]. So far there have been three patterns of the transmission of MERS-CoV virus mainly: sporadic cases [3], intra-familial transmissions [[4], [5], [6]] and healthcare-associated transmission [3,[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]]. The disease carries a high case fatality rate of 34.5% [1] and so far there has been no proven effective therapy and no approved therapies for MERS-CoV infection by international or national societies. Few therapeutic agents were reported in the literature but all were based on retrospective analysis. In this study, we review available literature on the current therapeutic options for the disease including in vitro, animal studies, and studies in human.

1.1. Search strategy

We searched four electronic databases: MEDLINE, Science Direct, Embase and Scopus for articles in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [27]. We used the following terms:

#1: “Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus” OR “MERS virus” OR “MERS Viruses” OR “MERS-CoV” OR “Novel Coronavirus” AND

#2: “Drug effect” OR “Drug Therapy” OR “Combination drug therapy” OR “Drug Ther*” OR “Combination drug ther*”

In addition, we reviewed the references of retrieved articles in order to identify additional studies or reports not retrieved by the initial search. The included studies were arranged as: in vitro studies, animal studies and human studies. We included studies conducted in the vitro, animal, or humans that measured the impact of drug therapy against MERS-CoV. We excluded studies that examined the impact of drug therapy against Coronaviruses other than MERS-CoV, any study that focused on drug synthesis and extractions, review articles, studies of supplemental therapy, and articles focused on the mechanism of action of medications.

2. Results

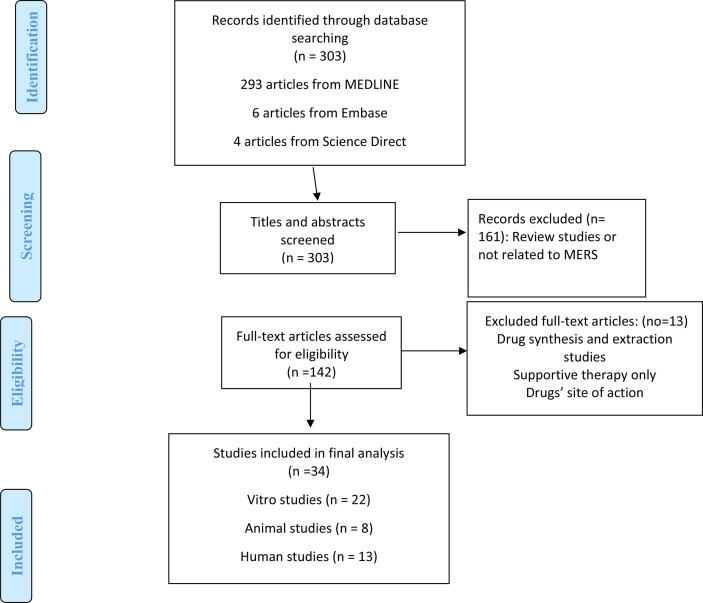

Initial search identified 62 articles: 52 articles were from Medline, 6 articles from Embase, and 4 articles from Science Direct. Of those, 32 studies were excluded: review studies (n = 16), drug synthesis and extraction (n = 3), supplemental therapy (n = 1), drug therapy in Coronavirus in general (n = 4), and site of action of different drugs modalities (n = 8). Based on the inclusions and exclusions criteria, only 30 articles were included in the final review: 13 studies were conducted in vitro, 8 studies were done in animal models, 8 studies were done in humans, and one study included both in vitro and animal model (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

A flow diagram of the search strategy according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [27].

2.1. In vitro studies

There were many in vitro studies evaluating various agents against MERS-CoV such as: interferon (INF), ribavirin, and HIV protease inhibitors (nelfinavir, ritonavir and lopinavir) as summarized in Table 1 . In vitro studies showed that IFN- β has a lower 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) for MERS-CoV compared with IFN-a2b [28]. In addition, IFN-β has a superior anti-MERS-CoV activity in the magnitude of 16-, 41-, 83- and 117-fold higher compared to IFN-α2b, IFN-γ, IFN-universal type 1 and IFN-α2a, respectively [28]. Pegylated Interferon-α (PEG-IFN-α) inhibited the effect of MERS-CoV at a dose of 1 ng/ml with complete inhibition of cytopathic effect (CPE) at doses of 3–1000 ng/ml in MERS-CoV infected Vero cells [29].

Table 1.

A summary of in Vitro Studies evaluating medications against MERS-CoV.

| Study type | Cell Type | Treatment | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [29] | In vitro Comparator study | MERS-CoV infected Vero cells and mock-infected Huh7 cells. | Cyclosporin 3 μg DMSO (a solvent control Control) |

No change in CPE |

| Cyclosporin 9 μg DMSO (a solvent control Control) |

CPE inhibited and no change on the cell viability on the infected Vero cells compared with mock-infected cells | |||

| MERS-CoV infected Huh7 cells and mock-infected Huh7 cells. | Cyclosporin 3.75 μg, 7.5 μg, and 15 μg | CPE reduced or inhibited by 7.5 μg and 15 μg Cyclosporine. | ||

| MERS-CoV infected Vero cells | PEG-INF-α2b at t = −4 h, t = 0 h, or t = 4 h of infection at doses range from 0 ng/ml to 1000 ng/ml | CPE reduced at 1 ng/ml and complete inhibition at doses 3, 10, 30, 100, 300, or 1000 ng/ml. | ||

| [30] | In vitro Comparator study | hCoV-EMC infected Vero cells | INF-α2b | IC50 = 58.08 U/ml, IC90 = 320.11 U/ml, and IC99 = 2061.89 U/ml CPE reduced at 250 U/ml and complete inhibition at ≥ 1000 U/ml Genome copies reduced by 0.53-log at 500 U/ml and highest reduction by 1.84-log at 5000 U/ml. Viral titer reduced by 0.57-log at 500 U/ml and highest reduction by 1.31-log at 5000 U/ml. |

| Ribavirin | IC50 = 41.45 μg/ml, IC90 = 92.15 μg/ml, and IC99 = 220.40 μg/ml CPE reduced at 100 μg/ml and complete inhibition at ≥ 200 μg/ml. Genome copies reduced by 0.82-log at 500 μg/ml and highest reduction by 2.04-log at 2000 μg/ml. Viral titer reduced by 1.24-log at 100 μg/ml and highest reduction by 4.05-log at 2000 μg/ml. |

|||

| INF-α2b + Ribavirin | CPE reduced at 12 μg/ml Ribavirin and 62 U/ml INF-α2b and complete inhibition at 25 μg/ml Ribavirin and 125 U/ml INF-α2b Ribavirin + INF-α2b at 1:5, Viral titer reduced by 0.4–2.16-log compared with INF-α2b alone. |

|||

| LLC-MK 2 infected cells | INF-α2b | IC50 = 13.26 U/ml, IC90 = 44.24 U/ml, and IC99 = 164.73 U/ml. Reduced viral protein level with increased dose starting at 250 U/ml. Viral titer reduced by 3.97-log at 2000 U/ml |

||

| Ribavirin | IC50 = 16.33 μ/ml, IC90 = 21.15 μg/ml, and IC99 = 28.02 μg/ml. Reduced viral protein level with dose 50 μg/ml (Not dose dependent) Viral titer reduced below the detection threshold of 13.7 TICD50/ml at 200 μg/ml |

|||

| INF-α2b + Ribavirin | Reduced viral protein level with dose INF-α2b 250U/ml and Ribavirin at 50 μg/ml. | |||

| [41] | In vitro Comparator study | Vero cells | Toremifene | EC50 = 12.9 μM with no virus reduction |

| Chlorpromazine | EC50 = 9.5 μM with no cytotoxicity Virus reduction by 3.1 log10 if dose >15 μM |

|||

| Chloroquine | No virus reduction | |||

| MDMs | Toremifene | Dose treated too low to determine EC50 with high cytotoxicity. Virus reduction by 1–1.5 log10 if dose >20 μM with increased in the toxicity. |

||

| Chlorpromazine | EC50 = 13.58 μM with high cytotoxicity CC50 = 25.64 μM, SI was 1.9 Virus reduction by 2 log10 with narrow therapeutic window and high toxicity |

|||

| Chloroquine | No antiviral activity and no cytotoxicity. | |||

| MDDCs | Toremifene | Virus reduction by 1–1.5 log10 if dose >20 μM with increased in the toxicity. | ||

| Chlorpromazine | Virus reduction by 2 log10 with narrow therapeutic window and high toxicity | |||

| Chloroquine | No antiviral activity and no cytotoxicity | |||

| [33] | In vitro Comparator study | Huh7 cells | Chloroquine Chlorpromazine Loperamide Lopinavir Pre-infection |

Chloroquine: dose-dependent, EC50 = 3.0 ± 1.1 μM and CC50 = 58.1 ± 1.1 μM, SI was 19.4 Chlorpromazine: Complete inhibition at 12 μM, EC50 = 4.9 ± 1.2 μM and CC50 = 21.3 ± 1.0 μM, SI was 4.3 Loperamide: Complete inhibition at 8 μM, EC50 = 4.8 ± 1.5 μM and CC50 = 15.5 ± 1.0 μM, SI was 3.2 Lopinavir: Complete inhibition at 12 μM, EC50 = 8 ± 1.5 μM and CC50 = 24.4 ± 1.0 μM, SI was 3.1 |

| [43] | In vitro Comparator study | Vero E6 MRC5 |

Imatinib in the first 4hrs of infection versus 5 h post infection | Iamtinib at time of infection is dose dependent. Viral level higher at post-infection compared to before infection (P < 0.05) Genomic RNA inhibited if drug added before infection (P < 0.05) but no effect if added post-infection CCF2 cleavage reduced by 80% (P < 0.001) |

| [49] | In vitro Comparator study | Pooled Plasma inoculated with MERS-CoV | Amotosalen and Ultraviolet A light | Viral titer reduced by 4.67 ± 0.25 log pfu/ml with no detection of the viable viruses. Viral genomic titer by RT-qPCR: no viral RNA had been detected on the treated cells |

| [44] | In vitro Comparator study | Huh-7 cells infected with MERS-CoV | Saracatinib | MERS-CoV infected cells: EC50 = 2.9 μM and CC50 > 50 μM, SI > 17, Dose 1 μM: viral titer reduced by > 50% (P < 0.05) with no effect on viral N protein after 24 h Dose 10 μM: reduced by 90% (P < 0.05) with complete depletion on the viral N protein after 24 h. Complete inhibition of viral genomic RNA and mRNA synthesis (P < 0.0001) Viral titer: Pretreatment: no difference At time of infection: marked reduction with significant a decrease of viral genomic RNA and mRNA synthesis. Post treatment (within 2 h): complete inhibition (P < 0.0001) Post treatment (after 4hrs): less effect (P < 0.05) |

| Huh-7 cells infected with rMERS-Cov. | Saracatinib | rMERS-CoV infected cells: EC50 = 9.3 μM | ||

| Huh-7 cells infected with rMERS-Cov-S2. | Saracatinib | rMERS-CoV-S2 infected cells: EC50 = 9.0 μM | ||

| Huh-7 cells infected with MERS-CoV | Gemcitabine | EC50 = 1.2 μM with complete viral depletion at dose ≥1 μM | ||

| Saracatinib + Gemcitabine | Synergistic effect at combination index of 0.529 Cytotoxicity: no difference compared with Saracatinib and less compared with Gemcitabine |

|||

| [45] | In vitro Comparator study | Vero E6 | Resveratrol | Reduced cell death at 125–250 μM (MTS assay P < 0.05, neutral red uptake assay P < 0.005) Less cytotoxicity even at higher concentration. Viral RNA level: At concentration 31.25–250 μM: after 48hr lower than after 24 h After 48 h at concentration 150 μM: lower (P < 0.05), at concentration 200 μM (P < 0.01), at concentration 250 μM (P < 0.001). If the drug added at time of infection: no difference in the cell proliferations and viral titers. After 24hr, the inhibition of N protein is dose dependent manner. At concentration 150 μM: limited decrease in the N protein At concentration 250 μM: elimination of N protein. Inhibited Caspase 3 cleavage: dose dependent manner. If drug administered consecutively at lower dose: Ever 24 h, dose ≤62.5 μM: the cell proliferation and cells viability were higher compared with untreated group (P < 0.001). The cytotoxicity and viral titer were lower (P < 0.001) |

| [46] | In vitro Comparator study | HAE infected with MERS-CoV | GS-441524 or Remdesivir (GS-5734) | GS-44152: EC50 = 0.86 μM Remdesivir: EC50 = 0.074 μM More reduction in viral titer if the drug were added 24–72 h post infection. |

| [47] | In vitro Comparator study | HAE infected with MERS-CoV | K22 | Significant reduction in the viral replication and dsRNA level. |

| [48] | In vitro Comparator study | MERS-CoV infected cells | Novel peptide (P9) | IC50 = 5 μg/ml >95% reduction at concentration > 25 μg/ml |

| [36] | In vitro Comparator study | Vero-TMPRSS2 infected cells | Camostat | At dose 10 μM, decreased viral entry by 15-fold |

| Vero-TMPRSS2- negative infected cells | Camostat | At dose 10 μM, no effect on the viral entry | ||

| Calu-3 cells | Camostat | At dose 10 μM, decreased viral entry by 10-fold Viral RNA suppressed by 90-fold Cell death delayed by 2 days post infection At dose 100 μM, Viral RNA suppressed by 270 folds 3 days post infection Cell death delayed by 5 days post infection |

||

| MRC-5 cells or WI-38 cells | Camostat | No effect on the viral RNA at 3 days post infection. At dose 10 μM, there was no effect on the cell death At dose 100 μM, the cell death partially suppressed. |

||

| Vero-TMPRSS2 infected cells | EST (an inhibitor of endosomal cathepsins) | At dose 10 μM, slight inhibition of viral entry | ||

| Vero-TMPRSS2- negative infected cells | EST (an inhibitor of endosomal cathepsins) | At dose 10 μM, inhibit viral entry | ||

| Calu-3 cells | EST (an inhibitor of endosomal cathepsins) | At dose 10 μM, slight inhibition of viral entry | ||

| Vero-TMPRSS2 infected cells | Camostat + EST (an inhibitor of endosomal cathepsins) | Decreased viral entry by 180-fold | ||

| Calu-3 cells MRC-5 cells WI-38 cells |

Camostat + EST + Leupeptin Single treatment + Leupeptin |

No significant difference in the viral entry | ||

| Vero-TMPRSS2- negative infected cells | Cathepsin L inhibitor Cathepsin K inhibitor |

Inhibit the viral entry by 40-fold | ||

| Vero-TMPRSS2- negative infected cells | Cathepsin B inhibitor Cathepsin S inhibitor |

No effect on the viral entry | ||

| Calu-3 cells | Leupeptin | Dose dependent effect Blocked viral entry at 10–100 μM |

||

| MRC-5 cells | Leupeptin | No effect on the viral entry | ||

| WI-38 cells | Leupeptin | No effect on the viral entry | ||

| [42] | In vitro Comparator study | Vero E6 cells infected with MERS-CoV | Chlorpromazine | EC50 = 9.51 μM with low toxicity |

| Triflupromazine | EC50 = 5.76 μM with low toxicity | |||

| Imatinib | EC50 = 14.69 μM with low toxicity | |||

| Dasatinib | EC50 = 5.47 μM with low toxicity | |||

| Nilotinib | No significant inhibition of MERS-CoV | |||

| Gemciatbine | EC50 = 1.22 μM with low toxicity | |||

| Toremifene | EC50 = 12.92 μM with low toxicity |

*CPE: cytopathic effect; PEG-INF: pegylated interferon; INF: interferon; IC50: inhibitory concentration of 50% of cells, IC90: inhibitory concentration of 90% of cells; IC99: inhibitory concentration of 99% of cells; EC50 and EC90: 50% and 90% maximal effective concentration; CC50: cytotoxicity concentration that kills 50% of cells; RT-qPCR: Real time Quantitative polymerase chain reaction;

Ribavirin, a nucleoside analog requiring activation by host kinases to a nucleotide, required high in vitro doses to inhibit MERS-CoV replications and these doses are too high to be achieved in vivo [30,31]. The combination of interferon-alfa 2b (INF-α2b) and ribavirin in Vero cells resulted in a an 8-fold reduction of the IFN-α2b dose and a 16-fold reduction in ribavirin dose [30].

The HIV protease inhibitors, Nelfinavir and lopinavir, were thoughts to inhibit MERS-CoV based on results from SARS [32]. Nelfinavir mesylate hydrate and lopinavir showed suboptimal 50% effective concentration (EC50) in the initial CPE inhibition assay and were not evaluated further [31]. In another study, the mean EC50 of lopinavir using Vero E6 and Huh7 cells was 8.0 μM [33].

MERS-CoV requires fusion to the host cells to replicate, thus MERS-CoV fusion inhibitors such as camostat and the Heptad Repeat 2 Peptide (HR2P) were evaluated in vitro [34,35]. Camostat inhibited viral entry into human bronchial submucosal gland-derived Calu-3 cells but not immature lung tissue [34]. HR2P was shown to inhibit MERS-CoV replication and the spike protein-mediated cell-cell fusion [35]. Camostat was effective in reducing viral entry by 15-folds in the Vero-TMPRSS2 cells infected with MERS-CoV [36].

Nitazoxanide, a broad-spectrum antiviral agent, and teicoplanin, an inhibitor of Cathepsin L in the Late Endosome/Lysosome cycle and a blocker of the entry of MERS-CoV, showed inhibitory effects of MERS-CoV in vitro [37,38].

The ability of recombinant receptor-binding domain (RBD-Fd) to inhibit MERS-CoV has been studied in DPP-4 expressing Huh-7 infected cells. The 50% inhibition dose (ID50) for RBD-Fd was 1.5 μg/ml compared with no inhibitory activity in untreated cells even at highest dose [39].

Cyclosporin affects the function of many cyclophilins that act as chaperones and facilitate protein folding [29,40]. In vitro, cyclosporine inhibited MERS-CoV replication [29,40]. Three days post infection, cytopathic effects (CPE) of MERS-CoV was inhibited by Cyclosporine Vero cells and mock-infected Huh7 cells [29].

Toremifene, Chlorpromazine, and Chloroquine were evaluated using Vero cells, human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) and immature dendritic cells (MDDCs) [41]. These drugs were transferred to cells 1 h prior to infection with MERS-CoV. After 48 h, viral replication was inhibited by Toremifene with 50% effective concentration (EC50) of 12.9 μM) but the MDMs dose was too low to have a calculated EC50. Chlorpromazine inhibited MERS-CoV in Vero cells with an EC50 of 9.5 μM and no cytotoxicity. In MDMs cells, the EC50 was 13.58 μM with high 50% cytotoxicity concentration (CC50) of 25.64 μM. Chloroquine showed no antiviral activity in the MDMs. Toremifene reduced virus by 1–1.5 log10 at a dose more than 20 μM. Chlorpromazine reduced MERS-CoV by 2 log10 and had a narrow therapeutic window and a high toxicity [41].

Chloroquine, Chloropromazine, and loperamide were tested on Huh7 cells [43]. The cells were treated 1-h prior to infection. Antiviral activity of chloroquine was dose-dependent. Chlorpomazine showed activity against MERS-CoV with EC50 of 4.9 ± 1.2 μM and CC50 of 21.3 ± 1.0 μM. Loperamide, an antidiarrheal drug, inhibited MERS-CoV and induced CPE. Two kinase signaling (ABL1) pathway inhibitors (Imatinib mesylate and Dasatinib) were active against MERS-CoV in vitro [42]. In Vero E6 and MRC5 cells imatinib had a dose dependent killing [43].

Saracatinib has a broad-spectrum antiviral activity against different strain of MERS-CoV. After 72 h of infection of Huh-7 cells, Saracatinib exhibited an EC50 of 2.9 μM and CC50 of more than 50 μM [44]. Whereas, gemcitabine was shown to be effective against MERS-CoV infected Huh-7 cells with an EC50 of 1.2 μM and a complete viral depletion at a dose of ≥1 μM [44]. Inhibitory effect of resveratrol against MERS-CoV was tested using infected Vero E6 cells. After 48 h, cell death was significantly reduced in the treatment group with resveratrol. The study showed that resveratrol inhibited MERS-CoV after entry in the cells and when resveratrol was added at same time of MERS-CoV, there was no difference in cell proliferations and viral titers compared with cells treated after infections [45].

The antiviral activity of GS-441524 and its pro-drug GS-5734 (Remdesivir) were tested on MERS-CoV infected human airway epithelial cell (HAE) [46]. GS-441524 has a mean EC50 of 0.86 μM and GS-5734 has a mean EC50 of 0.074 μM with more reduction in viral titer if the drug was added 24–72 h post infection [46].

Utilizing HAE cells infected with MERS-CoV, there was a significant reduction in viral replication and dsRNA level when cells were treated with K22 compound [47]. A novel peptide (P9) showed an in vitro activity against MERS-CoV at an IC50 of 5 μg/ml and more than 95% infection reduction at concentration higher than 25 μg/ml [48]. The two neurotransmitter antagonists (Chlorpromazine hydrochloride and triflupromazine hydrochloride) inhibit MERS-CoV infected Vero E6 cells [42]. The DNA synthesis and repair inhibitor, Gemcitabine Hydrochloride, and an Estrogen receptor I antagonist, Toremifene citrate, had antiviral activity against MERS-CoV [42]. An Estrogen receptor I antagonist, Toremifene citrate, had activity against MERS-CoV [42]. In addition, MERS-CoV is inactivated by amotosalen and ultraviolet light in fresh frozen plasma [49].

2.2. Animal studies

Monoclonal antibodies against MERS-CoV had been tested in animal models of MERS-CoV infection (Table 2 ). The monoclonal antibodies, 3B11–N and 4E10-N, were compared with no treatment in Rhesus Monkey model [50]. Antibodies, 3B11–N, were administered as a prophylaxis one-day prior to animal inoculation and showed significant reduction in lung disease radiographically. However, there was no significant difference when 3B11–N and 4E10-N were compared in term of lung pathology (P = 0.1122) [50].

Table 2.

A summary of the use of anti-viral agents for the treatment of MERS-CoV infection in animal model.

| Study type | Total # | Supportive therapy | Treatment plan | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [50] | Comparator trial | Rhesus monkey | No | 3B11–N antibody, 4E10-N antibody, or no treatment 1 day before inoculation (prophylaxis) | Less abnormal lung volume and less Lung pathology |

| [53] | Comparator trial | hDPP4-Tg mice | No | After 1 day of inoculation IV hMS-1 2 mg/kg versus Trastuzumab (Treatment) |

hMS-1 vs Tractuzumab:

|

| [54] | Comparator trial | Ad5-hCD26-transduced mice | No | Either 1d before or 1 d after inoculation IV mAb 4C2h (Prophylaxis and treatment) or no treatment |

Decreased Viral titer |

| [51] | Comparator trial | Rhesus macaques | No | Treatment group (#3): INF-α-2a SQ + Ribavirin IV No treatment group (#3) |

Decreased in oxygen saturation, increased white blood cells and neutrophils on day one more in no treatment Chest radiograph in the treated group showed light infiltration in a single lobe by day 2, and 3. Decrease viral load in treatment group. Untreated groups: increased in perivascular infiltrates. |

| [55] | Comparator trial | Ad5-hCD26-transduced mice | No | Treatment group: Intranasal peptide HR2P-M2 200mcg 6 h before inoculation (Prophylaxis) Control group (no treatment) |

Decreased viral titer |

| 1st gp: 200 mcg intranasal HR2P-M2 2nd gp: 2000 U intranasal INF-β 3rd gp: Combination 4th gp: no treatment 6 h before inoculation (prophylaxis) |

Decreased viral titer in all treated group compared with the control group with complete clearance in mice which received combination treatment. | ||||

| 1st gp: 200 mcg intranasal HR2P-M2 2nd gp: 2000 U intranasal INF-β 3rd gp: Combination 4th gp: no treatment 12 and 36 h after inoculation (treatment) |

Viral inhibition in all treated group with the greatest reduction in the combination group. greater reduction in viral titer in the HR2P-M2 alone vs INF-β alone. Reduced histopathologic change in INF- β and HR2P-M2 treated group with the greatest reduction in the combination group |

||||

| [56] | Comparator trial | hDPP-4 Tg mice | No | 1st gp: NbMS10-Fc single dose 2nd gp: Trastuzumab Before inoculation (prophylaxis) |

Better survival rate Steady weight compared with sharply decreased in the weight on the control group |

| 1st gp: NbMS10-Fc single dose 2nd gp: Trastuzumab 3d after inoculation (treatment) |

Better survival rate Less weight loss |

||||

| [52] | Comparator trial | 12 healthy common Marmosets | No | 1st gp: no treatment 2nd gp: Mycophenolate mofetil intraperitoneal after 8hr of inoculation 3rd gp: + Ritonavir PO at 6, 30, and 54 h after inoculation, 4th gp: INF- β-1b SQ at 8 and 56 h post inoculation. (Treatment) |

Lopinavir/Ritonavir and INF- β-1b have a better clinical score, less weight reduction, less radiological and pathological finding, and lower viral load in the lung and in the extrapulmonary The Mycophenolate has a higher viral load vs control group. The fatality rate was higher in untreated, and Mycophenolate vs treated groups |

| [57] | Comparator trial | Ad5-hDPP4-transduced mice | No | 1st gp: Intraperitoneal 100 or 500 mcg (5 or 25 mg/kg) of SAB-301 2nd gp: negative control Tc hIgG 500 mcg 3rd gp: no treatment 12 h before inoculation (prophylaxis) |

viral load was lower in SAB-301 vs Tc hIgG group at day 1 The viral titer was lowest in the 500mcg vs Tc hIgG and control |

| 1st gp: intraperitoneally single dose 500 mcg SAB-301 antibody, 2nd gp: intraperitoneally single dose Tc hIgG 3rd gp: no treatment 1–2 h of inoculation (Treatment) |

On day 1 and 2 post infection:

|

*mAb: monoclonal antibodies; INF: interferon; gp: group;

Interferon alfa-2a in conjunction with ribavirin were tested in rhesus macaques model of MERS-CoV infection. The animals were randomly assigned to either treatment or control groups and therapy was started 8 h post-infection. Necropsy showed a normal appearance of the lung in the treatment group compared with the control group. Virus replication was significantly reduced in the lung of treated animal. Serum interferon alfa was 37 times the level in untreated group by day 2. In addition, the treated group showed reduced systemic and local levels of pro-inflammatory markers such as interleukin-2, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, interleukin-2 receptor antagonist, interleukin-6, interleukin-15, and interferon-gamma [51].

Another study was conducted utilizing 12 healthy common marmosets inoculated with MERS-Cov and then assigned to four groups (control group; Mycophenolate mofetil intraperitoneally 8 h after inoculation; Lopinavir with Ritonavir at 6, 30, and 54 h after inoculation; or Interferon- Beta-1b subcutaneous at 8- and 56-h post inoculation) [52]. Lopinavir/Ritonavir and Interferon-beta- 1b treated groups had better clinical scores, less weight reduction, less pulmonary infiltrate, and lower viral load than the untreated group. The Mycophenolate group had a higher viral load with severe disease compared with the control group. The fatality rate was higher in untreated, and Mycophenolate treated groups (67%) than Lopinavir/Ritonavir treated and Interferon-Beta-1 b treated groups (0–33%) after 36 h of inoculation [52].

The human dipeptyl peptidase-4 (hDPP4) is a receptor for cell binding and entry of MERS-CoV. A transgenic mouse model with hDPP4 was utilized to test the effects of humanized mAb (hMS-1). In the model, a single dose of hMS-1 protected the transgenic mouse from MERS-CoV infection and all control mice died ten days post-infection [53].

The Humanized antibodies mAb 4C2h are mouse-derived neutralizing spike receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV (MERS-RBD) that were further humanized [54]. A single intravenous dose was injected one day pre and post MERS-CoV inoculation and showed that h-mAb-4C2h significantly decreased viral titer in the lungs in the mouse model (p < 0.05) [54].

Another study was done on adenoviruses expressing hDPP4 in mouse lungs (Ad5-hDPP4- Transduced mice) utilizing intranasal peptide derived from the heptad repeat (HR) 2 domain in S2 subunit known as HR2P analogue (HR2P-M2) [55]. The animals were either given intranasal HR2P-M2 6 h before infections or a control group with no treatment. The treated group showed decreased in the viral titer compared with the control group. The combination of HR2P-M2 with interferon β showed further reduction of infection [55].

The human-Fc-fused version of neutralizing nanobody (NbMS10-Fc) was tested using hDPP-4 transgenic mice model of MERS-CoV infection. The mice were injected with a single dose NbMS10-FC or Trastuzumab (control group) before a lethal dose of MESR-CoV. The treatment group had a 100% survival rate compared with 0% survival rate in the control group [56].

The impact of a trans-chromosomic (Tc) bovine, fully human polyclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies were tested on Ad5-hDPP4-transduced mice five days after transduction and 12 h before inoculated MERS-CoV. Animals received either intraperitoneal SAB-301 or control or Tc hIgG group. Viral load was lower in mice treated with SAB-301 at day 1 and 2 post-infection [57].

A recombinant trimeric receptor-binding protein (RBD-Fd) was tested on hDPP4 transgenic mice infected with MERS-CoV. The animals received RBD-Fd subcutaneously and were boosted at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, and 6 months. RBD-Fd induced S1-specific IgG antibodies against MERS-CoV and was maintained for at least 6 months. The survival rate in RBD-Fd immunized mice was 83% [39].

2.3. Human studies

A summary of the use of different therapeutic agents in human is shown in Table 3 . The first use of antiviral agents to treat MERS-CoV infection was observed in 5 patients in 2013 in Saudi Arabia [58]. All patients received ribavirin orally and subcutaneous interferon alfa-2b. Unfortunately, all patients died at 1–2 months due to respiratory and multi-organ failure and four patients experienced adverse drug reaction such as thrombocytopenia, anemia and pancreatitis [58].

Table 3.

A summary of human studies of the use of anti-viral therapy for the treatment of MERS-CoV infection.

| Study type | Total # | Supportive therapy | Treatment plan | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [60] | Retrospective cohort study Treatment group (n = 20) versus control group (n = 24) |

44 patients | Yes | SQ PEG-INF α-2a + PO Ribavirin for 8–10 days: |

Survival rate after 14 days was 70% versus 29% (P = 0.004) but no change after 28 days (30% versus 17%; P = 0.054) Decreased hemoglobin level as a side effect of ribavirin |

| [58] | Retrospective observational studies | Two patients | Yes | 1st patient: SQ PEG-INF α- 2b + PO Ribavirin | There was a drop in hemoglobin level The patient improved and discharge home |

| Yes | 2nd patient: SQ PEG-INF α- 2b 1 for 3 days + Ribavirin PO | After 14 days the patient recovered from MERS-CoV. Died after two months as a result of MDR and hospital-acquired infections |

|||

| [59] | Retrospective observational studies | 5 patients | Yes | Ribavirin for 5 days + SQ INF α-2b | Died from multi-organ failure |

| Yes | Ribavirin for 5 days + SQ INF α-2b for 2 doses. | Drop in platelet Died from multi-organ failure |

|||

| Yes | Ribavirin PO for 5 days + SQ INF α-2b. | Patient developed pancreatitis Died from multi-organ failure |

|||

| Yes | Ribavirin PO for 5 days + SQ INF α-2b for 2 doses. | hemoglobin dropped and bilirubin increased and dialysis was required Died from multi-organ failure |

|||

| Yes | Ribavirin PO for 5 days + SQ INF α-2b for 2 doses. | Increased lipase Died from multi-organ failure |

|||

| [63] | Case report | 1 patient | No | Lopinavir/Ritonavir PO + Ribavirin PO + PEG-INF α-2a SQ | Improved No fever after 2 days Discharge after 9 days Developed hemolytic anemia, electrolyte disturbance, and kidney and liver dysfunction. |

| [62] | Retrospective Cohort Study | 24 patients | Yes | 1st gp: 13 pts INF- α-2a SQ + PO Ribavirin 2nd gp: 11 pt INF-β-1a + PO Ribavirin |

The fatality rate was 85% in INF-α-2a vs 64% in INF-β-1a. |

| [65] | Case series | 2 patients | Yes | 1st patient as treatment and 2nd patient as prophylaxis SQ PEG-INF- α-2b: Ribavirin PO |

Complete recovery and discharge home. |

| [71] | case series | 11 | ribavirin and interferon-alfa 2a | Survival of all patients | |

| [70] | Randomized control trial | The enrollment began in Nov. 2016 | 100 mg Lopinavir/100 mg Ritonavir PO q12 h for 14 days + INF- β1b 0.25 mg/ml SQ on alternative days for 14 days. | Result is not yet published | |

| [66] | Case series | 23 | Interferon beta | 18/23 (78.3) | |

| [66] | Case series | 8 | Interferon alpha | 6/8 (75) | |

| [66] | Case series | 19 | Ribavirin | 13/19 (68.4) | |

| [66] | Case series | 8 | Mycophenolate mofetil | 8/8 (100) | |

| [72] | case report | 1 | ribavirin and interferon-alfa 2a day 12 from onset |

died | |

| [67] | case series | 6 | ribavirin and interferon-alfa 2b | 3/6 (50) | |

*PEG-INF: pegylated interferon; gp: group.

In 2015, two patients with MERS-Cov infection in Kuwait were treated with pegylated interferon alfa-2b subcutaneously and oral ribavirin [59]. One patient was discharged home after 42 days of starting antiviral therapy and ribavirin was stopped after one week of therapy due to anemia. The second patient recovered from MERS-CoV and he subsequently died two months later with multidrug-resistant organism [59].

A large retrospective cohort study included 44 adult patients. Of those patients, 24 patients (control group) did not receive antiviral treatment, and 20 patients received subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2a and oral ribavirin [60] per previously developed protocol [61]. The survival rate after 14 days from the date of diagnosis was statistically higher in the treatment group compared with the control group (70% versus 29%; P = 0.004). However, the survival rate did not differ in the two groups at 28 days (30% versus 17%; P = 0.054) [60].

In 2014, a retrospective cohort study was conducted on 24 confirmed MERS cases in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia and were started on day one of MERS-CoV confirmation [62]. Of those patients, 13 received interferon α-2a subcutaneous per week and 11 patients received interferon β-1a subcutaneous three times weekly. Both groups also received ribavirin orally. The case fatality rate was 85% in INF-α-2a versus 64% in INF-β-1a (p = 0.24). The fatality rate in patients using INF with positive MERS-CoV RT-PCR was 90% versus 44% in those with negative MERS-CoV RT-PCR test [62].

In 2015, pegylated interferon-α-2b and ribavirin was given to two confirmed cases in Riyadh. One patient was treated PEG-INF- α-2b and ribavirin and start to improve day 6 and had complete recovery at day 18. The second case was not a confirmed case and was started on these medication as a prophylaxis. On the fourth day, the patient started to improve and was discharged home after two weeks [63]. The combination therapy was also used in other case reports (Table 3), [64,65].

In a large cohort study of 51 patients, various combinations of interferon and ribavirin were used with different outcomes (Table 3) [66]. Another small study utilized ribavirin and interferon-alfa 2b in three patients who received therapy within 1–2 days of admission and were compared to three other patients who received therapy 12–19 days after admission [67]. The first group survived and the latter group died [67]. The use of interferon beta, interferon alpha, and ribavirin was associated with survival rates of 78.3%, 75%, and 68.4%, respectively [66].

Oral lopinavir and ritonavir were used for the treatment of a 64 years old Korean male with confirmed MERS-CoV infection. These medications were started on the fourth day of admission and the patient achieved full recovery after nine days of treatment [63]. One patient was treated with pegylated interferon, ribavirin and lopinavir/ritonavir and viremia was detected for two days following therapy with triple therapy [64]. In a case series, eight patients received mycophenolate mofetil and all survived [66].

A phase 1 randomized placebo-controlled study utilized a fully human polyclonal IgG antibody (SAB-301) and evaluated the safety and tolerability of this agent in 28 adults compared with 10 adults who received placebo [68]. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02788188. SAB-301 was well tolerated and the most reported adverse events were headache, elevated creatinine kinase, and albuminuria [68].

3. Discussion

Since the emergence of MERS-CoV infection there was a large interest in the development of an effective therapy for this disease. In this review, we summarized the available literature on possible therapeutic options including in vitro, animal and human studies. In vitro studies showed superiority of IFN-β compared to IFN-α2b, IFN-γ, IFN-universal type 1 and IFN-α2a [28] and PEG-IFN-α had excellent CPE inhibition [29]. Moreover, the combination of INF-α2b and ribavirin in Vero cells showed augmentation of action and facilitates the reduction of the doses of IFN-α2b and ribavirin to lower concentrations suggesting possible utility in clinical use [30]. Saracatinib with Gemcitabine had no difference in cytotoxicity compared with Saracatinib alone but was less cytotoxic compared with gemcitabine alone [44]. There were many drugs that were used in vitro and showed effectiveness, however, translating the findings from these studies into clinical trial remains of particular importance especially taking into consideration availability, pharmacokinetic properties, pharmacodynamic characteristics and possible side effects [69].

Avaialble clincial experience regarding the therapy for MERS-CoV relies on limited case reports and observational case-series. The most widely used combination is ribavirin and IFN and experience comes from limited case reports and a number of observational studies. These studies are non-homogeneous in nature and thus a common conclusion could not be obtained to make firm recommendations for the use of this combination in routine clinical practice outside of prospective clinical studies [69].

The combination of lopinavir/ritonavir and interferon-beta- 1b was used in common marmosets [52] and was used in two patients with good outcome [[63], [64], [65]]. This combination is being considered in a randomized control trial in Saudi Arabia. The enrollment for the study began in November 2016 and the results are not available yet [70]. The study was registered on 27 July 2016 at ClinicalTrials.gov, with an ID: NCT02845843. And this is the only currently ongoing clinical therapeutic trial for MERS-CoV therapy.

In conclusion, despite multiple studies in humans there is no consensus on the optimal therapy for MERS-CoV. Randomized clinical trials are needed and potential therapies should be evaluated only in such clinical trials. Thus, any such therapy should be used in conjunction with clinical trials. An interesting strategy is repurposing old drugs against MERS-CoV and this deserves further consideration and use in clinical setting.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Middle W.H.O. East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) - update: 2 DECEMBER 2013 2013. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_12_02/en/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Auwaerter P.G. Healthcare-associated infections: the hallmark of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) with review of the literature. J Hosp Infect. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Drivers of MERS-CoV transmission: what do we know? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2016;10:331–338. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2016.1150784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omrani A.S., Matin M.A., Haddad Q., Al-Nakhli D., Memish Z.A., Albarrak A.M. A family cluster of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections related to a likely unrecognized asymptomatic or mild case. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e668–e672. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Memish Z.A., Zumla A.I., Al-Hakeem R.F., Al-Rabeeah A a, Stephens G.M. Family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2487–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memish Z.A., Cotten M., Watson S.J., Kellam P., Zumla A., Alhakeem R.F. Community case clusters of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in hafr Al-batin, kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a descriptive genomic study. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;23:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.03.1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drosten C., Muth D., Corman V.M., Hussain R., Al Masri M., HajOmar W. An observational, laboratory-based study of outbreaks of middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Jeddah and Riyadh, kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;60:369–377. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu812. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Alhakeem R.F., Assiri A., Alharby K.D., Almahallawi M.S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus ( MERS-CoV ): a cluster analysis with implications for global management of suspected cases. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2015;13:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Bushra H.E., Abdalla M.N., Al Arbash H., Alshayeb Z., Al-Ali S., Latif Z.A.-A. An outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) due to coronavirus in Al-Ahssa region, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2015;22:468–475. 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balkhy H.H., Alenazi T.H., Alshamrani M.M., Baffoe-Bonnie H., Al-Abdely H.M., El-Saed A. Notes from the field: nosocomial outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in a large tertiary care hospital--Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;65:163–164. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506a5. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balkhy H.H., Alenazi T.H., Alshamrani M.M., Baffoe-Bonnie H., Arabi Y., Hijazi R. Description of a hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in a large tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1147–1155. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Assiri A.M., Biggs H.M., Abedi G.R., Lu X., Bin Saeed A., Abdalla O. Increase in Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus cases in Saudi Arabia linked to hospital outbreak with continued circulation of recombinant virus. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofw165. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw165. July 1-August 31, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nazer R.I. Outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus causes high fatality after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:e127–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.02.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assiri A., Abedi G.R., Bin Saeed A.A., Abdalla M.A., al-Masry M., Choudhry A.J. Multifacility outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in Taif, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:32–40. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter J.C., Nguyen D., Aden B., Al Bandar Z., Al Dhaheri W., Abu Elkheir K. Transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in healthcare settings, Abu dhabi. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:647–656. doi: 10.3201/eid2204.151615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cauchemez S., Van Kerkhove M.D., Riley S., Donnelly C.A., Fraser C., Ferguson N.M. Vol. 18. pii; 2013. Transmission scenarios for middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and how to tell them apart; p. 20503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cauchemez S., Fraser C., Van Kerkhove M.D., Donnelly C.A., Riley S., Rambaut A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: quantification of the extent of the epidemic, surveillance biases, and transmissibility. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:50–56. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M., Price C.S., Al Rabeeah A.A., Cummings D.A.T. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chowell G., Abdirizak F., Lee S., Lee J., Jung E., Nishiura H. Transmission characteristics of MERS and SARS in the healthcare setting: a comparative study. BMC Med. 2015;13:210. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0450-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Abdallat M.M., Payne D.C., Alqasrawi S., Rha B., Tohme R.A., Abedi G.R. Hospital-associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1225–1233. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hijawi B., Abdallat M., Sayaydeh A., Alqasrawi S., Haddadin A., Jaarour N. Novel coronavirus infections in Jordan, April 2012: epidemiological findings from a retrospective investigation. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19(Suppl 1):S12–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oboho I.K., Tomczyk S.M., Al-Asmari A.M., Banjar A.A., Al-Mugti H., Aloraini M.S. MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah--a link to health care facilities. N Engl J Med. 2014;372:846–854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408636. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alraddadi B., Bawareth N., Omar H., Alsalmi H., Alshukairi A., Qushmaq I. Patient characteristics infected with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in a tertiary hospital. Ann Thorac Med. 2016;11:128–131. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.180027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fagbo S.F., Skakni L., Chu D.K.W., Garbati M.A., Joseph M., Peiris M. Molecular epidemiology of hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;21 doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150944. 2015. 1981–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almekhlafi G.A., Albarrak M.M., Mandourah Y., Hassan S., Alwan A., Abudayah A. Presentation and outcome of Middle East respiratory syndrome in Saudi intensive care unit patients. Crit Care. 2016;20:123. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1303-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saad M., Omrani A.S., Baig K., Bahloul A., Elzein F., Matin M.A. Clinical aspects and outcomes of 70 patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a single-center experience in Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;29:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3:e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hart B.J., Dyall J., Postnikova E., Zhou H., Kindrachuk J., Johnson R.F. Interferon-β and mycophenolic acid are potent inhibitors of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in cell-based assays. J Gen Virol. 2014;95:571–577. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.061911-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Wilde A.H., Raj V.S., Oudshoorn D., Bestebroer T.M., van Nieuwkoop S., Limpens R.W.A.L. MERS-coronavirus replication induces severe in vitro cytopathology and is strongly inhibited by cyclosporin A or interferon-α treatment. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:1749–1760. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.052910-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falzarano D., de Wit E., Martellaro C., Callison J., Munster V.J., Feldmann H. Inhibition of novel β coronavirus replication by a combination of interferon-α2b and ribavirin. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1686. doi: 10.1038/srep01686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan J.F., Chan K.H., Kao R.Y., To K.K., Zheng B.J., Li C.P. Broad-spectrum antivirals for the emerging Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect. 2013;67:606–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu C.-Y., Jan J.-T., Ma S.-H., Kuo C.-J., Juan H.-F., Cheng Y.-S.E. Small molecules targeting severe acute respiratory syndrome human coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci Unit States Am. 2004;101:10012–10017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Wilde A.H., Jochmans D., Posthuma C.C., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J.C., van Nieuwkoop S., Bestebroer T.M. Screening of an FDA-approved compound library identifies four small-molecule inhibitors of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication in cell culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4875–4884. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03011-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shirato K., Kawase M., Matsuyama S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection mediated by the Transmembrane serine protease TMPRSS2. J Virol. 2013;87:12552–12561. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01890-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu L., Liu Q., Zhu Y., Chan K.-H., Qin L., Li Y. Structure-based discovery of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion inhibitor. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3067. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shirato K., Kawase M., Matsuyama S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection mediated by the Transmembrane serine protease TMPRSS2. J Virol. 2013;87:12552–12561. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01890-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nitazoxanide Rossignol J-F. A new drug candidate for the treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9:227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou N., Pan T., Zhang J., Li Q., Zhang X., Bai C. Glycopeptide Antibiotics potently inhibit Cathepsin L in the late Endosome/Lysosome and block the entry of Ebola virus, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) J Biol Chem. 2016;291:9218–9232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.716100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tai W., Zhao G., Sun S., Guo Y., Wang Y., Tao X. A recombinant receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV in trimeric form protects human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (hDPP4) transgenic mice from MERS-CoV infection. Virology. 2016;499:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Wilde A.H., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J.C., van der Meer Y., Thiel V., Narayanan K., Makino S. Cyclosporin A inhibits the replication of diverse coronaviruses. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:2542–2548. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.034983-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cong Y., Hart B.J., Gross R., Zhou H., Frieman M., Bollinger L. MERS-CoV pathogenesis and antiviral efficacy of licensed drugs in human monocyte-derived antigen-presenting cells. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dyall J., Coleman C.M., Hart B.J., Venkataraman T., Holbrook M.R., Kindrachuk J. Repurposing of clinically developed drugs for treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4885–4893. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03036-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coleman C.M., Sisk J.M., Mingo R.M., Nelson E.A., White J.M., Frieman M.B. Abelson kinase inhibitors are potent inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion. J Virol. 2016;90:8924–8933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01429-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shin J.S., Jung E., Kim M., Baric R.S., Go Y.Y. Saracatinib inhibits Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus replication in vitro. Viruses. 2018;10:283. doi: 10.3390/v10060283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin S.-C., Ho C.-T., Chuo W.-H., Li S., Wang T.T., Lin C.-C. Effective inhibition of MERS-CoV infection by resveratrol. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:144. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agostini M.L., Andres E.L., Sims A.C., Graham R.L., Sheahan T.P., Lu X. Coronavirus susceptibility to the antiviral Remdesivir (GS-5734) is mediated by the viral polymerase and the proofreading Exoribonuclease. mBio. 2018;9 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00221-18. pii: e00221-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lundin A., Dijkman R., Bergström T., Kann N., Adamiak B., Hannoun C. Targeting membrane-bound viral RNA synthesis reveals potent inhibition of diverse coronaviruses including the middle East respiratory syndrome virus. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao H., Zhou J., Zhang K., Chu H., Liu D., Poon V.K.-M. A novel peptide with potent and broad-spectrum antiviral activities against multiple respiratory viruses. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22008. doi: 10.1038/srep22008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hindawi S.I., Hashem A.M., Damanhouri G.A., El-Kafrawy S.A., Tolah A.M., Hassan A.M. Inactivation of Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus in human plasma using amotosalen and ultraviolet A light. Transfusion. 2018;58:52–59. doi: 10.1111/trf.14422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson R.F., Bagci U., Keith L., Tang X., Mollura D.J., Zeitlin L. 3B11-N, a monoclonal antibody against MERS-CoV, reduces lung pathology in rhesus monkeys following intratracheal inoculation of MERS-CoV Jordan-n3/2012. Virology. 2016;490:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Falzarano D., de Wit E., Rasmussen A.L., Feldmann F., Okumura A., Scott D.P. Treatment with interferon-α2b and ribavirin improves outcome in MERS-CoV-infected rhesus macaques. Nat Med. 2013;19:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/nm.3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan J.F.-W., Yao Y., Yeung M.-L., Deng W., Bao L., Jia L. Treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir or interferon-β1b improves outcome of MERS-CoV infection in a nonhuman primate model of common marmoset. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1904–1913. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qiu H., Sun S., Xiao H., Feng J., Guo Y., Tai W. Single-dose treatment with a humanized neutralizing antibody affords full protection of a human transgenic mouse model from lethal Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-coronavirus infection. Antivir Res. 2016;132:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Y., Wan Y., Liu P., Zhao J., Lu G., Qi J. A humanized neutralizing antibody against MERS-CoV targeting the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein. Cell Res. 2015;25:1237–1249. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Channappanavar R., Lu L., Xia S., Du L., Meyerholz D.K., Perlman S. Protective effect of intranasal Regimens containing peptidic Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion inhibitor against MERS-CoV infection. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1894–1903. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao G., He L., Sun S., Qiu H., Tai W., Chen J. A novel nanobody targeting Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) receptor-binding domain has potent cross-neutralizing activity and protective efficacy against MERS-CoV. J Virol. 2018;92 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00837-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luke T., Wu H., Zhao J., Channappanavar R., Coleman C.M., Jiao J.-A. Human polyclonal immunoglobulin G from transchromosomic bovines inhibits MERS-CoV in vivo. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:326ra21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tawalah H., Al-Qabandi S., Sadiq M., Chehadeh C., Al-Hujailan G., Al-Qaseer M. The most effective therapeutic regimen for patients with severe Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection. J Infect Dis Ther. 2015;03:1–5. doi: 10.4172/2332-0877.1000223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Momattin H., Dib J., Memish Z.A. Ribavirin and interferon therapy in patients infected with the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: an observational study. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;20:42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Omrani A.S., Saad M.M., Baig K., Bahloul A., Abdul-Matin M., Alaidaroos A.Y. Ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a for severe Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:1090–1095. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70920-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Momattin H., Mohammed K., Zumla A., Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfiq J.A. Therapeutic options for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)--possible lessons from a systematic review of SARS-CoV therapy. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e792–e798. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shalhoub S., Farahat F., Al-Jiffri A., Simhairi R., Shamma O., Siddiqi N. IFN-α2a or IFN-β1a in combination with ribavirin to treat Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus pneumonia: a retrospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2129–2132. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim U.J., Won E.-J., Kee S.-J., Jung S.-I., Jang H.-C. Combination therapy with lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin and interferon-alpha for Middle East respiratory syndrome: a case report. Antivir Ther. 2015 doi: 10.3851/IMP3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spanakis N., Tsiodras S., Haagmans B.L., Raj V.S., Pontikis K., Koutsoukou A. Virological and serological analysis of a recent Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection case on a triple combination antiviral regimen. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;44:528–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khalid M., Al Rabiah F., Khan B., Al Mobeireek A., Butt T.S., Al Mutairy E. Ribavirin and interferon-α2b as primary and preventive treatment for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a preliminary report of two cases. Antivir Ther. 2015;20:87–91. doi: 10.3851/IMP2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Al Ghamdi M., Alghamdi K.M., Ghandoora Y., Alzahrani A., Salah F., Alsulami A. Treatment outcomes for patients with middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV) infection at a coronavirus referral center in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:174. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1492-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khalid M., Khan B., Al Rabiah F., Alismaili R., Saleemi S., Rehan-Khaliq A.M. Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome corona virus (MERS CoV): case reports from a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2014;34:396–400. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2014.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beigel J.H., Voell J., Kumar P., Raviprakash K., Wu H., Jiao J.-A. Safety and tolerability of a novel, polyclonal human anti-MERS coronavirus antibody produced from transchromosomic cattle: a phase 1 randomised, double-blind, single-dose-escalation study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:410–418. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Update on therapeutic options for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2017;15:269–275. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2017.1271712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arabi Y.M., Alothman A., Balkhy H.H., Al-Dawood A., AlJohani S., Al Harbi S. Treatment of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome with a combination of lopinavir-ritonavir and interferon-β1b (MIRACLE trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:81. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Khalid I., Alraddadi B.M., Dairi Y., Khalid T.J., Kadri M., Alshukairi A.N. Acute management and Long-term survival Among subjects with severe Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus pneumonia and ARDS. Respir Care. 2016;61:340–348. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Malik A., El Masry K.M., Ravi M., Sayed F. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus during pregnancy, Abu dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;22 doi: 10.3201/eid2203.151049. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]