Abstract

Background

Viral respiratory tract infections are known to be common in Hajj pilgrims while the role of bacteria is less studied.

Methods

Clinical follow-up, adherence to preventive measures and PCR-based pharyngeal bacterial carriage pre- and post-Hajj, were assessed in a cohort of 119 French Hajj pilgrims.

Results

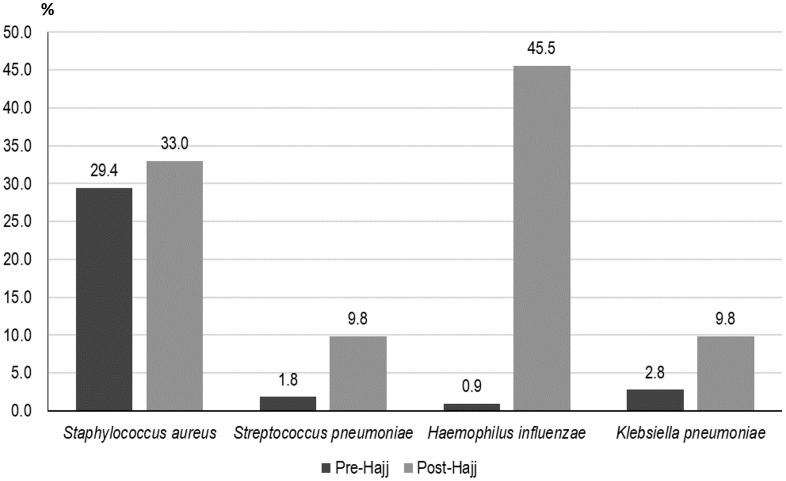

55% had an indication for pneumococcal vaccination. Occurrence of respiratory symptoms was 76.5%, with cough (70.6%) and sore throat (44.5%) being the most frequent; fever was reported by 38.7% pilgrims and 42.0% took antibiotics. Respiratory symptoms, fever and antibiotic intake were significantly more frequent in pilgrims with indication for vaccination against pneumococcal infection. The prevalence of S. pneumoniae carriage (1.8% pre-, 9.8% post-Hajj), H. influenzae carriage (0.9%, 45.4%) and K. pneumoniae (2.8%, 9.8%) significantly increased post-Hajj. Pilgrims vaccinated with conjugate pneumococcal vaccine were seven time less likely to present S. pneumoniae carriage post-Hajj compared to those not vaccinated (3.2% vs. 18.0%, OR = 0.15; 95% CI [0.03–0.74], p = 0.02).

Conclusions

Pilgrims at risk for pneumococcal disease are more likely to suffer from febrile respiratory symptoms at the Hajj despite being immunized against pneumococcal disease and despite lowered S. pneumoniae carriage and should be targeted for reinforced prevention against respiratory infections.

Keywords: Hajj, Respiratory infections, Prevention, Pneumococcal vaccine, Bacteria

1. Introduction

The Hajj is one of the largest annual religious mass gatherings in the world. Each year, Saudi Arabia attracts over 2 million pilgrims from more than 180 countries including about 2000 from Marseille, France [1]. The Hajj presents major challenges in public health and infection control and the crowding conditions favor the acquisition, dissemination and transmission of pathogenic microorganisms [2]. Respiratory diseases are particularly common during the pilgrimage, representing a significant cause of morbidity and a major cause of hospitalization with community-acquired pneumonia being a leading cause of serious illness among pilgrims [3]. The etiology of respiratory tract infection is multifactorial and complex. Whereas viruses are likely responsible for mild upper respiratory tract infections [4], some studies have identified Streptococcus pneumoniae as one of the main etiologic agents associated with severe respiratory infections in Hajj pilgrims [5]. Predisposing factors for pneumococcal infections at the Hajj include older age, chronic diseases, overcrowding conditions and environmental pollution [6]. The natural route of pneumococcal infection is initiated by nasopharyngeal colonization and may progress towards an invasive disease, especially if natural immunological barriers are crossed [7]. The reported rates of S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal carriage depend on age, geographical area, genetic heritage and socio-economic conditions [7]. This nasopharyngeal carriage is considered as the principal source of person-to-person transmission of S. pneumoniae [7]. In addition to S. pneumoniae other bacterial pathogens such as Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus were frequently isolated from Hajj pilgrims suffering from pneumonia [[8], [9], [10]]. However, available data about the carriage of S. pneumoniae and other respiratory bacteria in the overall population of Hajj pilgrims is limited [3,5].

The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence of pharyngeal carriage of respiratory bacteria including S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, K. pneumoniae and S. aureus in French pilgrims, before and after the Hajj in 2015.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and study design

Pilgrims participating in the 2015 Hajj (from September 21st to 26th, 2015) were recruited in August 2015, at a private specialized travel agency in Marseille, France, which organizes trips to Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Potential adult participants were asked to participate in the study on a voluntary basis. They were included and followed up before departing from France and immediately before leaving Saudi Arabia by a medical bilingual (Arabic and French) doctor who traveled with the group. Upon inclusion (August 23rd to 30th, 2015), the participants were interviewed using a standardized pre-Hajj questionnaire that collected information on demographics, immunization status and medical history. Based on French recommendations [12,13], pilgrims with risk factors for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) such as age superior or equal to 60 years, diabetes mellitus, chronic respiratory disease, chronic heart disease, chronic kidney disease and immunodeficiency, were vaccinated with the 13-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-13) unless they received the vaccine in the past 5 years. A post-Hajj questionnaire that collected clinical data and information on compliance with face masks use as well as hand washing, use of disinfectant hand gel and disposable handkerchiefs, was completed during a face-to-face interview, 2 days before the pilgrims’ return to France. Pharyngeal swabs were collected upon inclusion on August 30th (pre-Hajj specimens) and 2 days prior to the return of the pilgrims on September 30th, 2015 (post-Hajj specimens). Influenza-like illness (ILI) was defined as the presence of cough, sore throat and subjective fever [14]. The protocol was approved by the Aix-Marseille University institutional review board (July 23rd, 2013; reference no. 2013-A00961-44). The study was performed in accordance with the good clinical practices recommended by the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. All participants provided written consent.

Respiratory specimen. Pharyngeal swabs were collected from each participant, transferred to Sigma-Virocult® medium and stored at −80 °C.

Identification of respiratory bacteria. The DNA extractions were concurrently performed using the EZ1 Advanced XL (Qiagen, German) with the DNA Kit v2.0 (Qiagen). Real-time PCR amplifications were carried out by using LightCycler® 480 Probes Master kit (Roche diagnostics, France) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. All real-time PCR reactions were performed using a C1000 Touch™ Thermal Cycle (Bio-Rad, USA). Positive results of bacteria amplification were defined as those with a cycle threshold (CT) value ≤ 35. The SDD gene of H. influenzae, phoE gene of K. pneumoniae, nucA gene of S. aureus and lytA gene of S. pneumoniae were amplified with internal DNA extraction controls TISS, as previously described [15].

2.2. Statistical analysis

Differences in the proportions were tested by Pearson's chi-square or Fisher's exact tests when appropriate. To evaluate the potential acquisition of respiratory pathogens in Saudi Arabia, we used the McNemar's Test to compare their prevalence before leaving France and in Saudi Arabia (during and after the Hajj). Percentages and odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) estimations and comparisons were carried out using STATA 11.1 (Copyright 2009 StataCorp LP, https://www.stata.com/). A p value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of study participants

A total of 119 persons of the 131 pilgrims who traveled with the travel agency (90.8%) agreed to participate and answered the pre- and post-travel questionnaires; 12 pilgrims were excluded because they joined the group in Saudi Arabia one week after the main group arrived. 62 pilgrims were male (52.1%) and 57 female (47.9%) with a gender ratio of 1:1. The median age was 61 years of age (ranging from 24 to 81 years). Fifty-nine (50.9%) of the 119 participants were over 60 years of age. Sixty-five pilgrims (54.6%) had an indication for vaccination against IPD according to French recommendation at the time of inclusion. Diabetes was the most common comorbidity (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics and comorbidities of 119 pilgrims according to vaccination status against invasive pneumococcal disease.

| Socio-demographic characteristics and comorbidities | Total N = 119 |

Vaccinated pilgrims n = 62 |

Unvaccinated pilgrims n = 57 |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Male | 62 (52.1) | 30 (48.4) | 32 (56.1) |

| Female | 57 (47.9) | 32 (51.6) | 25 (43.9) |

| Median age [IQR]a (years) | 61 [52; 66] | 65 [63; 69] | 52.5 [34; 58] |

| Age ≥ 60 yearsb | 59 (50.9) | 57 (91.9) | 2 (3.7) |

| previous Hajj | 13 (10.9) | 9 (14.5) | 4 (7.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 39 (32.8) | 36 (58.1) | 3 (5.3) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 12 (10.1) | 12 (19.4) | 0 (0) |

| Chronic heart disease | 8 (6.7) | 7 (11.3) | 1 (1.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) |

| Immunodeficiency | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Indication for vaccination against invasive pneumococcal diseasec | 65 (54.6) | 62 (100) | 3d (5.3) |

Interquartile range.

Data based on 116 individuals, data from three participants were missing.

Age of 60 years or over, diabetes mellitus, chronic respiratory disease, chronic heart disease, chronic kidney disease and immunodeficiency.

Refused vaccination.

Regarding preventive measures, 4.2% (5/119) of pilgrims reported pneumococcal vaccination (PCV-13) in the past 5 years and 57 were vaccinated upon inclusion (three refused), so 62/119 (52.1%) of them were immunized. Ninety-eight pilgrims (82.4%) reported using face masks during the Hajj, including 68.1% (81/119) who reported using masks sometimes and 14.3% frequently (17/119). 47.1% (56/119) declared washing their hands during the Hajj more often than usual, 37.0% (44/119) used hand gel and 41.2% (49/119) used disposable handkerchiefs during their stay in Saudi Arabia.

3.2. Clinical features

During the three weeks of their stay in Saudi Arabia, 91 (76.5%) pilgrims reported at least one respiratory symptom with cough being the most frequent (70.6%, 84/119), followed by sore throat (44.5%, 53/119), rhinitis (37.0%, 44/119), voice failure (15.1%, 18/119) and dyspnea (6.7%, 8/119). 38.7% (46/119) reported fever and 20.2% (24/119) ILI. A proportion of 42.0% (50/119) received antibiotics for respiratory tract infection symptoms. The highest antibiotic consumption was β-lactams (42/50, 84.0%), followed by macrolides (5/50, 10.0%). None of the pilgrims suffered from pneumonia or other invasive pneumococcal diseases and none was hospitalized.

Overall, respiratory symptoms, ILI and antibiotic intake were more frequent in pilgrims vaccinated against IPD compared to those who were unvaccinated (Table 2 ). These differences were statistically significant for cough, sore throat and antibiotic intake. Prevalence of cough, fever and antibiotic intake was higher among those who reported using face masks.

Table 2.

Prevalence of symptoms and antibiotic intake during Hajj according to preventive measures.

| Preventive measures | Cough | Dyspnea | Sore throat | Voice failure | Rhinitis | Fever | ILI | ATB | ||||||||||

| n (%) | OR [CI 95%] p | n (%) | OR [CI 95%] p | n (%) | OR [CI 95%] p | n (%) | OR [CI 95%] p | n (%) | OR [CI 95%] p | n (%) | OR [CI 95%] p | n (%) | OR [CI 95%] p | n (%) | OR [CI 95%] p | |||

| Vaccination against IPD | Yes | 50 (80.6) | 2.82 [1.24–6.42] p = 0.01 | 7 (11.3) | 7.12 [0.85–59.85] p = 0.07 | 33 (53.2) | 2.1 [1.01–4.4] p = 0.05 | 11 (11.7) | 1.54 [0.55–4.29] p = 0.41 | 26 (41.9) | 1.56 [0.74–3.32] p = 0.24 | 29 (46.8) | 2.07 [0.97–4.4] p = 0.06 | 16 (13.4) | 2.13 [0.83–5.45] p = 0.12 | 32 (51.6) | 2.31 [1.09–4.88] p = 0.03 | |

| No | 34 (59.7) | 1 (1.8) | 20 (35.1) | 7 (12.3) | 18 (31.6) | 17 (29.8) | 8 (6.7) | 18 (31.6) | ||||||||||

| Mask | Yes | 73 (74.5) | 2.65 [1.01–7.00] p = 0.05 | 6 (6.1) | 0.62 [0.12–3.31] p = 0.58 | 46 (46.9) | 1.77 [0.66–4.76] p = 0.26 | 16 (16.3) | 1.85 [0.39–8.75] p = 0.44 | 38 (38.8) | 1.58 [0.56–4.44] p = 0.38 | 42 (42.9) | 3.19 [1.00–10.17] p = 0.05 | 23 (23.5) | 6.13 [0.78–48.22] p = 0.08 | 46 (46.9) | 3.76 [1.18–11.98] p = 0.02 | |

| No | 11 (52.4) | 2 (9.5) | 7 (33.3) | 2 (9.5) | 6 (28.6) | 4 (19.0) | 1 (0.8) | 4 (19.0) | ||||||||||

| Hand washing | More often than usual | 38 (67.9) | 0.78 [0.35–1.72] p = 0.54 | 5 (8.9) | 1.96 [0.45–8.61] p = 0.37 | 23 (41.1) | 0.77 [0.37–1.58] p = 0.47 | 11 (19.6) | 1.96 [0.7–5.45] p = 0.2 | 22 (34.9) | 1.2 [0.57–2.54] p = 0.62 | 20 (35.7) | 0.79 [0.38–1.66] p = 0.54 | 8 (6.7) | 0.49 [0.19–1.25] p = 0.14 | 24 (42.9) | 1.07 [0.51–2.21] p = 0.86 | |

| As usual | 46 (73.0) | 3 (4.8) | 30 (47.6) | 7 (11.1) | 22 (39.3) | 26 (41.3) | 16 (13.4) | 26 (41.3) | ||||||||||

| Disinfectant gel | Yes | 32 (72.7) | 1.18 [0.52–2.69] p = 0.7 | 0 (0) | NA p = 0.02 | 22 (50.0) | 1.42 [0.67–3] p = 0.36 | 7 (15.9) | 1.1 [0.39–3.08] p = 0.86 | 17 (38.6) | 1.12 [0.52–2.41] p = 0.77 | 14 (31.8) | 0.63 [0.29–1.37] p = 0.24 | 9 (7.6) | 1.03 [0.41–2.6] p = 0.95 | 18 (40.9) | 0.93 [0.44–1.98] p = 0.85 | |

| No | 52 (69.3) | 8 (10.8) | 31 (41.3) | 11 (14.7) | 27 (36.0) | 32 (42.7) | 15 (12.6) | 32 (42.7) | ||||||||||

| Disposable handkerchiefs | Yes | 36 (73.5) | 1.27 [0.56–2.85] p = 0.56 | 2 (4.1) | 0.45 [0.09–2.35] p = 0.35 | 21 (42.7) | 0.89 [0.43–1.86] p = 0.76 | 7 (14.3) | 0.89 [0.32–2.5] p = 0.83 | 20 (40.8) | 1.32 [0.62–2.81] p = 0.47 | 23 (46.9) | 1.81 [0.85–3.83] p = 0.12 | 10 (8.4) | 1.02 [0.41–2.54] p = 0.96 | 22 (44.9) | 1.22 [0.58–2.56] p = 0.59 | |

| No | 48 (68.6) | 6 (8.6) | 32 (45.7) | 11 (15.7) | 24 (34.3) | 23 (32.9) | 14 (11.8) | 28 (40.0) | ||||||||||

NA: not applicable.

IPD: invasive pneumococcal disease, OR: Odds ratio, CI 95%: 95% confidence interval; ILI: influenza like illness, ATB: Antibiotic treatment.

3.3. Detection of respiratory bacteria

Pre- and post-Hajj specimens were collected from 109 (91.6%) and 112 (94.1%) participants, respectively. The prevalence of bacterial carriage significantly increased after participation in Hajj, compared to pre-Hajj status. S. pneumoniae carriage increased from 1.8% pre-Hajj to 9.8% post-Hajj (p = 0.01). The prevalence of H. influenzae carriage increased from 0.9% pre-Hajj to 45.4% post-Hajj (p < 0.0001). The prevalence of K. pneumoniae increased from 2.8% pre-Hajj to 9.8% post-Hajj (p = 0.02). S. aureus carriage increased from 29.4% in pre-Hajj samples to 33.0% in post-Hajj samples but the difference was not statistically significant with p = 0.46 (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of bacterial carriage in pre- and post-Hajj pharyngeal samples.

Pilgrims vaccinated against IPD were seven time less likely to harbor S. pneumoniae after the Hajj compared to unvaccinated pilgrims (3.2% vs. 18.0%, OR = 0.15; 95% CI [0.03–0.74], p = 0.02). Using disinfectant gel was significantly associated with an increased S. aureus carriage after the Hajj. Pilgrims using disposable handkerchiefs were 3 times less likely to be positive for H. influenzae in post-Hajj samples. Antibiotic intake was significantly associated with increased carriage of K. pneumoniae in post-Hajj samples (Table 3 ). We also compared the carriage rate of the four respiratory bacteria in pre-Hajj samples according to adherence to preventive measures during the Hajj for potential confounding factors and found no significant difference (data not shown). When analyzing the relationship between the carriage of the four respiratory bacteria in post-Hajj samples and the prevalence of clinical symptoms, no significant differences were observed.

Table 3.

Bacterial carriage in post-Hajj pharyngeal samples according to preventive measures and antibiotic intake.

| Preventive measures |

Staphylococcus aureus |

Streptococcus pneumoniae |

Haemophilus influenzae |

Klebsiella pneumoniae |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR CI 95% | p | n (%) | OR CI 95% | p | n (%) | OR CI 95% | p | n (%) | OR CI 95% | p | ||

| Vaccination against IPD | Yes | 18 (29.0) | 0.67 [0.30–1.47] | 0.32 | 2 (3.2) | 0.15 [0.03–0.74] | 0.02 | 26 (41.9) | 0.72 [0.34–1.53] | 0.40 | 7 (11.3) | 1.46 [0.40–5.31] | 0.56 |

| No |

19 (38.0) |

9 (18) |

25 (50.0) |

4 (8.0) |

|||||||||

| Mask | Yes | 35 (36.1) | 3.67 [0.78–17.21] | 0.10 | 8 (8.2) | 0.36 [0.08–1.54] | 0.17 | 45 (46.4) | 1.30 [0.43–3.93] | 0.64 | 9 (9.3) | 0.66 [0.13–3.42] | 0.62 |

| No |

2 (13.3) |

3 (20.0) |

6 (40.0) |

2 (13.3) |

|||||||||

| Hand washing | Much more | 20 (35.7) | 1.27 [0.58–2.81] | 0.55 | 6 (10.7) | 1.22 [0.35–4.27] | 0.75 | 27 (48.2) | 1.24 [0.59–2.61] | 0.57 | 7 (12.5) | 1.86 [0.51–6.74] | 0.94 |

| As usual |

17 (30.4) |

5 (8.9) |

24 (42.9) |

4 (7.1) |

|||||||||

| Disinfectant gel | Yes | 19 (44.2) | 2.24 [1.01–5.03] | 0.05 | 7 (16.3) | 3.16 [0.87–11.53] | 0.08 | 17 (39.5) | 0.67 [0.31–1.46] | 0.32 | 6 (14.0) | 2.08 [0.59–7.27] | 0.25 |

| No |

18 (26.1) |

4 (5.8) |

34 (49.3) |

5 (7.2) |

|||||||||

| Disposable handkerchiefs | Yes | 12 (24.5) | 0.49 [0.22–1.12] | 0.09 | 3 (6.1) | 0.45 [0.11–1.79] | 0.26 | 16 (32.6) | 0.39 [0.18–0.84] | 0.02 | 6 (12.2) | 1.62 [0.46–5.65] | 0.45 |

| No |

25 (39.7) |

8 (12.7) |

35 (55.6) |

5 (7.9) |

|||||||||

| Antibiotic treatment | Yes | 18 (36.0) | 1.27 [0.58–2.81] | 0.55 | 4 (8.0) | 0.68 [0.19–2.48] | 0.56 | 22 (44.0) | 0.89 [0.42–1.89] | 0.77 | 9 (18.0) | 6.58 [1.35–32.06] | 0.02 |

| No | 19 (30.6) | 7 (11.3) | 29 (46.8) | 2 (3.2) | |||||||||

IPD: invasive pneumococcal disease, OR: Odds ratio, CI 95%: 95% confidence interval.

4. Discussion

We confirm here that upper respiratory tract symptoms are very frequent in French Hajj pilgrims, leading to an excessive consumption of antibiotics [16]. On the other hand, our study showed a significantly increased carriage of S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae and K. pneumoniae following participation in Hajj, confirming previous results obtained from cohort studies conducted among French pilgrims [17,18] and from a large cohort study enrolling pilgrims from 13 countries [15]. Such bacterial acquisition is worrying since these pathogens are frequently responsible for Hajj-associated pneumonia [[8], [9], [10]] or may be responsible for acute rhinosinusitis [11].

We demonstrate here that vaccination against IPD with a conjugate vaccine had a significant protective effect against pneumococcal carriage following participation in the Hajj. Additionally, none of the pilgrims in our cohort suffered from pneumonia. The impact of vaccination against IPD on the reduction of the acquisition of S. pneumoniae respiratory carriage and on the prevention of pneumococcal disease in adults is well-described in the literature, especially in at-risk patients, including those with bronchial asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic heart failure, splenectomy or immunodeficiency [19]. Consistent local or national official recommendations on the use of pneumococcal vaccine for Hajj pilgrims are lacking [6,[20], [21], [22]]. The recent recommendations of the Saudi Thoracic Society for pneumococcal vaccination before the Hajj season are to vaccinate all persons aged 50 years and over with combined pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 13 and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23 [23]. 54.6% of the participants in our study had chronic diseases, making them at risk for IPD, or were aged 60 years and over, which is the age cut-off for recommended pneumococcal vaccination in Hajj pilgrims according to French medical authorities [12]. If the Saudi recommendation were to be applied, this proportion would have been 73.3%. In our study, 32.8% of the participants were diabetic. A similar proportion was found in a study conducted in patients hospitalized for severe pneumonia during the 2013 Hajj with a 34.8% prevalence of diabetes mellitus [9]. Respiratory symptoms and antibiotic consumption were more frequent in pilgrims with indication for vaccination against IPD in our survey. This apparently paradoxical result is likely due to the fact that pilgrims with indication for vaccination against IPD were older, more likely to present with chronic respiratory disease, diabetes or other chronic conditions making them at higher risk for respiratory infections due to S. pneumoniae for which they were protected by vaccination or due other respiratory pathogens for which they were not protected. This finding indicates that criteria used to identify pilgrims at risk for IPD could indeed qualify for pre-screening of pilgrims at higher risk for any respiratory infection and help targeting them for reinforced measures against pulmonary communicable diseases including vaccination against influenza, reinforced hand hygiene practice and use of face masks.

When looking at non-pharmaceutical preventive measures against respiratory infections, our results showed that while a majority of pilgrims used face-masks at least sometimes during their stay in Saudi Arabia, only 14.3% used masks frequently and less than half reported compliance with frequent hand washing, use of disinfectant hand-gel and disposable handkerchiefs. Wearing masks especially when in crowded places, frequent hand washing with soap and water or disinfectant, especially after coughing and sneezing, and the use of disposable handkerchiefs are recommended by the Saudi Ministry of Health [24]. Only 8.4% of the Hajj pilgrims wore masks during the H1N1 outbreak in 2009 and less than 1% wore masks during the MERS-CoV epidemic in 2013 [5]. In our survey, cough, fever and antibiotic consumption were significantly more frequent in individuals using face masks, which likely accounts for the high willingness of pilgrims suffering from febrile cough to wear a face mask, with the aim of avoiding spreading diseases. We have no explanation for the positive association between the use of hand gel and the prevalence of S. aureus carriage in post-Hajj throat samples. The negative association between the use of disposable handkerchief and H. influenzae carriage in post-Hajj throat samples may possibly reflect an increased removal of organisms by cleaning of the nasopharynx. The 6-fold increase in K. pneumoniae carriage in post-Hajj samples in individuals who consumed antibiotics during their stay in Saudi Arabia compared to those who did not may possibly be indicative of the high capacity of K. pneumoniae to acquire antibiotic resistance genes under antibiotic selective pressure [25].

Our study had several limitations. The sample size was small and only limited numbers of patients infected with bacteria were recruited. The study was conducted in French pilgrims only and our results cannot be extrapolated to all pilgrims. Information regarding observance of prevention measures was self-reported and subjective. Also, qPCR does not distinguish between living and dead microorganisms and does not allow assessing antibiotic susceptibility. Finally, we did not investigate vaccine pneumococcal serotypes.

5. Conclusions

Hajj pilgrims acquire bacterial pathogens during Hajj, which is a risk for disease especially among the significant population of at-risk individuals among pilgrims. Vaccination with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine appears to reduce the carriage rate of S. pneumoniae among the vaccinated. Further studies based on larger numbers of pilgrims are needed in order to confirm our preliminary findings.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French Government under the « Investissements d’avenir » (Investments for the Future) program managed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR, fr: National Agency for Research), (reference: Méditerranée Infection 10-IAHU-03).

References

- 1.Gautret P., Gaillard C., Soula G., Delmont J., Brouqui P., Parola P. Pilgrims from Marseille, France, to Mecca: demographics and vaccination status. J Trav Med. 2007;14:132–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Memish Z.A., Zumla A., Alhakeem R.F., Assiri A., Turkestani A., Al Harby K.D. Hajj: infectious disease surveillance and control. Lancet. 2014;383:2073–2082. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60381-0. https://doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60381-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Gautret P., Benkouiten S., Memish Z.A. Mass gatherings and the spread of respiratory infections. Lessons from the Hajj. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:759–765. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-772FR. https://doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-772FR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gautret P., Benkouiten S., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Hajj-associated viral respiratory infections: a systematic review. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:92–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.12.008. https://doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Prevention of pneumococcal infections during mass gathering. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12:326–330. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1058456. https://doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1058456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridda I., King C., Rashid H. Pneumococcal infections at Hajj: current knowledge gaps. Infect Disord - Drug Targets. 2014;14:177–184. doi: 10.2174/1871526514666141014150323. https://doi:10.2174/1871526514666141014150323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogaert D., Veenhoven R.H., Sluijter M., Sanders E.A., de Groot R., Hermans P.W. Colony blot assay: a useful method to detect multiple pneumococcal serotypes within clinical specimens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;41:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandourah Y., Al-Radi A., Ocheltree A.H., Ocheltree S.R., Fowler R.A. Clinical and temporal patterns of severe pneumonia causing critical illness during Hajj. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-117. https://doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirah B.H., Zafar S.H., Alferaidi O.A., Sabir A.M.M. Mass gathering medicine (Hajj Pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia): the clinical pattern of pneumonia among pilgrims during Hajj. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.04.016. https://doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Memish Z.A., Almasri M., Turkestani A., Al-Shangiti A.M., Yezli S. Etiology of severe community-acquired pneumonia during the 2013 Hajj-part of the MERS-CoV surveillance program. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;25:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.06.003. https://doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marglani O.A., Alherabi A.Z., Herzallah I.R., Saati F.A., Tantawy E.A., Alandejani T.A. Acute rhinosinusitis during Hajj season 2014: prevalence of bacterial infection and patterns of antimicrobial susceptibility. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:583–587. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haut Conseil de la santé publique. Bull Epidemiol Hebdo. Recommandations sanitaires pour les voyageurs. 2015. https://invs.santepubliquefrance.fr/beh/2015/reco/pdf/2015_reco.pdf

- 13.Direction Générale de la Santé Ministère des Affaires sociales, de la Santé et des Droits des femmes. Paris. Calendrier des vaccinations et recommandations vaccinales. 2015. http://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Calendrier_vaccinal_2015.pdf 2015.

- 14.Rashid H., Shaf S., El Bashir H., Haworth E., Memish Z.A., Ali K.A. Influenza and the Hajj: defining influenza-like illness clinically. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:102–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Memish Z.A., Assiri A., Turkestani A., Yezli S., Al Masri M., Charrel R. Mass gathering and globalization of respiratory pathogens during the 2013 Hajj. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.008. https://doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.008 571.e1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gautret P., Benkouiten S., Griffiths K., Sridhar S. The inevitable Hajj cough: surveillance data in French pilgrims, 2012-2014. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2015;13:485–489. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.09.008. https://doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benkouiten S., Charrel R., Belhouchat K., Drali T., Nougairede A., Salez N. Respiratory viruses and bacteria among pilgrims during the 2013 Hajj. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1821–1827. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140600. https://doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benkouiten S., Gautret P., Belhouchat K., Drali T., Salez N., Memish Z.A. Acquisition of Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage in pilgrims during the 2012 Hajj. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:e106–e109. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit749. https://doi: 10.1093/cid/cit749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonten M.J., Huijts S.M., Bolkenbaas M., Webber C., Patterson S., Gault S. Polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1114–1125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408544. https://doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rashid H., Abdul Muttalif A.R., Mohamed Dahlan Z.B., Djauzi S., Iqbal Z., Karim H.M. The potential for pneumococcal vaccination in Hajj pilgrims: expert opinion. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2013;11:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.06.001. https://doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Gautret P., Memish Z.A. Expected immunizations and health protection for Hajj and Umrah 2018 - an overview. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2017;19:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.10.005. https://doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel D. The Hajj and umrah: health protection matters. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2017;19:1. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.10.013. https://doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alharbi N.S., Al-Barrak A.M., Al-Moamary M.S., Zeitouni M.O., Idrees M.M., Al-Ghobain M.O. The Saudi Thoracic Society pneumococcal vaccination guidelines-2016. Ann Thorac Med. 2016;11:93–102. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.177470. https://doi:10.4103/1817-1737.177470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health Health requirements and recommendations for travelers to Saudi Arabia for Hajj and umrah – 2018/1439H. 2018. http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/hajj/pages/healthregulations.aspx

- 25.Navon-Venezia S., Kondratyeva K., Carattoli A. Klebsiella pneumoniae: a major worldwide source and shuttle for antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2017;41:252–275. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux013. http://doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]