Abstract

Dysregulation of airway nerves leads to airway hyperreactivity, a hallmark of asthma. Although changes to nerve density and phenotype have been described in asthma, the relevance of these changes to nerve function has not been investigated due to anatomical limitations where afferent and efferent nerves run in the same nerve trunk, making it difficult to assess their independent contributions. We developed a unique and accessible system to activate specific airway nerves to investigate their function in mouse models of airway disease. We describe a method to specifically activate cholinergic neurons using light, resulting in immediate, measurable increases in airway inflation pressure and decreases in heart rate. Expression of light-activated channelrhodopsin 2 in these neurons is governed by Cre expression under the endogenous choline acetyltransferase promoter, and we describe a method to decrease variability in channelrhodopsin expression in future experiments. Optogenetic activation of specific subsets of airway neurons will be useful for studying the functional relevance of other observed changes, such as changes to nerve morphology and protein expression, across many airway diseases, and may be used to study the function of subpopulations of autonomic neurons in lungs and other organs.

Keywords: optogenetics, parasympathetic, cre, peripheral nervous system, electrophysiology

Airway nerves are dysfunctional in asthma (1). In the lungs, parasympathetic nerves provide the dominant autonomic control of airway tone and mediate bronchoconstriction (2). They are also part of a reflex arc that is triggered by sensory nerves and relayed via the central nervous system. We have shown that epithelial sensory nerve density is increased in asthma (3), while blocking parasympathetic nerves reduces airway tone and blocks vagally-mediated and reflex-mediated bronchoconstriction. Studies in animals have shown that airway hyperreactivity is mediated by parasympathetic nerves after antigen sensitization and challenge, infection with parainfluenza, exposure to ozone or organophosphate pesticides, and obesity (4–8). Gi-coupled M2 muscarinic receptors on postganglionic parasympathetic nerves normally limit acetylcholine release in healthy airways, but in animal models of airway hyperreactivity, and in humans with allergic asthma, M2 receptors decrease their inhibition of acetylcholine release, resulting in increased bronchoconstriction (1, 9–11).

Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve is the most common method for studying its function in vivo, but results obtained with this method are complicated by the many different types of neurons in the vagus, including multiple types of both sensory and autonomic neurons, and by regulatory effects of vagal activation on sympathetic outflow (12). Current methods rely on pharmacological blockade, neurodestruction with capsaicin, or tight control of electrical stimulation parameters, but there is always a concern about specificity of action even with these controls. Therefore, there is a need for better tools to study nerves in the peripheral nervous system and, given the important role that nerves play in asthma, in airways in particular.

In this article, we have used optogenetics (13), or light activation of neurons, to specifically activate cholinergic nerves in vivo. Simultaneously, we recorded bronchoconstriction caused by the specific activation of these cholinergic neurons. Our method can additionally be adapted to target other nerve populations. This new technique will allow us to evaluate the contribution of cholinergic parasympathetic neurons, as well as other nerve populations, to airway responses in asthma and other airway diseases.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures complied with Oregon Health & Science University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Transgenic mice expressing a floxed stop codon before channelrhodopsin 2 (CH2) fused to enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP; CH2–EYFP mice, #024109; Jackson Laboratory) and mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by the choline acetyltransferase (CHAT) promoter (CHAT-Cre mice, #028861; Jackson Laboratory) were bred to create mice with CH2 expressed in cholinergic neurons (CHAT-CH2 mice). Heterozygous mice were crossed with one another to form a homozygous CHAT-CH2 line. All mice were on a C57BL/6 background. Male and female mice 12 weeks of age and older were used for experiments.

Tissue Optical Clearing and Imaging of Airway Nerves

Mice were perfused with PBS and airways were excised and left at 4°C in Zamboni fixative (Newcomer Supply) overnight. Tracheas were blocked overnight with 4% normal goat serum, 1% Triton X-100, and 5% powdered milk, and then incubated overnight with antibodies to EYFP (anti-GFP chicken IgY, 1:500; Invitrogen) and panneuronal marker protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5, rabbit IgG, 1:500; Millipore) on a shaker at 4°C. Tissues were washed and incubated overnight in secondary antibodies (Alexa goat anti-rabbit 647, 1:1,000; Invitrogen; Alexa goat anti-chicken 488, 1:1,000; Invitrogen) before optical clearing for 12 hours in N-methylacetamide/Histodenz (Ce3D) (14). Tracheas were mounted in Ce3D on slides in silicon imaging wells and imaged using an LSM 880 confocal microscope. Samples were illuminated with 488 nm and 633 nm light, and images were acquired as z-stacks and converted to maximum intensity projections. Tiled images were obtained of each trachea, extending from the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle to the carina. All PGP9.5-positive and EYFP-positive nerve cell bodies within the area were quantified (see Figure E1 in the data supplement). All EYFP-positive cell bodies were PGP9.5 positive.

Ventilation and Physiological Measurements

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg i.p.), tracheotomized, and ventilated as previously described (15). A 21-gauge catheter was inserted into the cricothyroid membrane to the level of the second cartilage ring. Mice were mechanically ventilated with 100% oxygen at 120 breaths/min with a tidal volume of 150 μl and a positive end-expiratory pressure of 2 cm H2O. Mice were paralyzed with succinylcholine (0.05 mg in 0.05 ml i.p.) to eliminate respiratory effort. Some mice were injected with the cholinesterase inhibitor, physostigmine (0.5 mg/kg i.p.), and/or the muscarinic antagonist atropine (3 mg/kg i.p.). Body temperature was maintained at 37°C with a heat lamp, homeothermic blanket, and rectal probe. Heart rate and rhythm were measured by electrocardiogram recorded with three needle electrodes placed subcutaneously on the right hindpaw, left forepaw, and left shoulder. Airway pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, tidal volume, body temperature, and flow were all measured using LabChart Pro acquisition software (ADInstruments).

Optogenetic Activation of Nerves In Vivo

A midline skin incision was made extending 1 cm caudally from the base of the neck over the thorax. Soft tissue and muscle were retracted to expose the sternum to the level of the first two ribs, and this section of sternum was removed without lacerating the major blood vessels. If the thymus was visible, a 2-mm section from the proximal end was removed to allow a clear light path to the trachea. Muscle around the trachea was resected, and tissue was held to each side with clamps. Damp gauze was placed over the exposed trachea between light stimulations to prevent desiccation.

A high-power 454-nm light-emitting diode (LED) light source (Prizmatix) coupled to an optic fiber with a 500-μm core diameter was attached to a collimator (numerical aperture = 0.63) to create a 1-cm circle of light with 8.9-mW/mm2 intensity. A 555-nm LED light source was also used as a control. The light was positioned immediately ventral to the exposed trachea, centered midway between the larynx and carina. Light activation, frequency, pulse width, and pulse number were controlled by a Master-8 system pulse stimulator (A.M.P.I.).

Quantitative PCR of Lung Tissue and Submandibular Glands

Sections of lung tissue and submandibular gland were surgically excised. RNA was extracted by Qiagen RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), and reverse transcribed with SuperScript III (Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified using QuantiTect SYBR Green on the Veriti 96-well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems). Primers specific for EYFP, PGP9.5, and Cre recombinase were synthesized (Table E2; Integrated DNA Technologies), and the cycle thresholds (CT values) for PCR products were measured with 7,500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

Electrophysiology Recording of Parasympathetic Neurons

Tracheas were removed from anesthetized mice and were submerged in room temperature Krebs buffer containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 21.4 NaHCO3, 11.1 D-glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, ∼305 mOsm, and incubated in 0.02 mg/ml Liberase (Thermolysin Medium; Roche) for 30 minutes. Tracheas were then washed in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) for another 20 minutes while being saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Recordings were obtained at near-physiological temperature (32–34°C) from slices superfused with oxygenated aCSF.

Electrophysiology Data Acquisition

Borosilicate pipettes (2.5–3 MΩ; Sutter Instruments) were filled with potassium gluconate-based internal solution (in mM): 110 potassium gluconate, 10 KCl, 15 NaCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 1 EGTA, 2 Na2ATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, 7.8 phosphocreatine; pH 7.35–7.40; ∼280 mOsm. Tracheal parasympathetic ganglionic neurons were identified by morphology and by their expression of EYFP. Optically evoked inward currents were recorded in whole-cell voltage-clamp mode at −70 mV holding potential. Optically evoked depolarizations were recorded in whole-cell current clamp mode.

All recordings were acquired using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Molecular Devices), digitized at 20 kHz (Instrutech ITC-16), and recorded (Axograph X software). Optically evoked currents were elicited by LED illumination through the microscope objective (Olympus, BX51W with 60×, 1.0 numerical aperture water immersion objective. For LED stimulation a transistor to transistor logic (TTL)-controlled LED driver and 470 nm LED (Thorlabs) were used to illuminate the slice directly over the recorded cell generally with approximately 1 mW of power for 1 ms.

Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test was used for airway pressure and heart rate data. Linear regressions were used for assessment of CH2 expression in both imaging and quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software).

Results

Optogenetic Activation of Thoracic Cholinergic Nerves Leads to Bronchoconstriction and Heart Rate Reduction

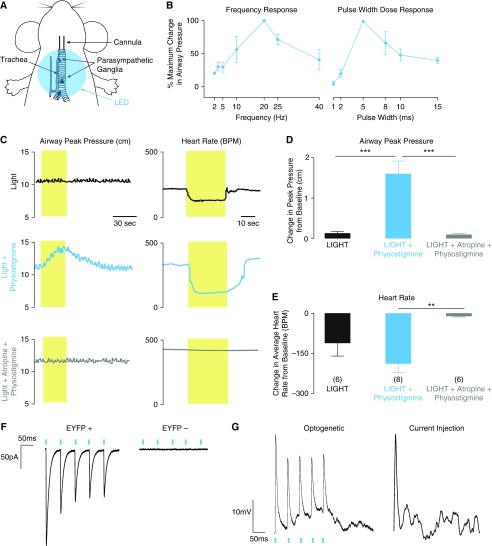

Bronchoconstriction and bradycardia were measured during 30 seconds of light at increasing pulse frequencies (2–40 Hz) and pulse widths (1–15 ms) in the presence of physostigmine. Light of 20-Hz frequency and 5-ms pulse width caused the largest increase in airway pressure (Figure 1B), and was used in subsequent experiments. Each CHAT-CH2 mouse was exposed to three pulse trains of light over 20 minutes: an initial pulse train (light), a pulse train given 15 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 mg/ml physostigmine to block degradation of acetylcholine by cholinesterase (light + physostigmine), and a pulse train given 5 minutes after a further intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg/ml atropine to block muscarinic receptors (light + physostigmine + atropine). Without pharmacological intervention, light caused small increases in airway pressure. Physostigmine dramatically increased the response to light (Figures 1C–1E). In both the absence and presence of physostigmine, light-induced bronchoconstriction and bradycardia reversed rapidly upon cessation of light stimulation. In addition, both bronchoconstriction and bradycardia were blocked by atropine, confirming these effects were mediated by release of acetylcholine onto muscarinic receptors. Wild-type animals had no airway pressure or heart rate response when exposed to light, even after giving physostigmine, and CHAT-CH2 mice had no response when the 454-nm LED light was replaced with light in the red spectrum (555 nm; Figure E2).

Figure 1.

Optogenetic activation of airway cholinergic neurons leads to bronchoconstriction: (A) Diagram of ventilated mouse showing area of light-emitting diode (LED) illumination. (B) Increase in peak pressure during light activation at different frequencies and pulse widths, reported as a percentage of the maximum peak airway pressure increase for each mouse. Maximum increases in airway pressure were achieved using 20-Hz light with a pulse width of 5 ms. (C) Representative traces of airway peak pressure and heart rate effects after optogenetic activation. Airway peak pressures increased substantially in the presence of physostigmine. This effect was blocked by atropine. (D and E) Maximum peak airway pressure increases (D) and heart rate decreases (E) over the 30-second period of light activation (n = 6–8 as indicated; mean ± SEM; **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001). (F) Whole-cell patch clamp of enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)-positive cells showed light-induced inward currents, which were absent in neurons not expressing channelrhodopsin 2 (CH2)-EYFP. (G) Optogenetic activation of airway neurons and current injection led to similar levels of depolarization in EYFP-positive cells. BPM = beats per minute.

Electrophysiologic Recordings Confirm Light Response of CH2-Expressing Parasympathetic Neurons

To verify CH2 effect in parasympathetic neurons, we performed whole cell patch-clamp recording of parasympathetic neurons in homozygous mice (CH2+/+ CHAT+/+). We observed inward currents (Figure 1F) and cell depolarization equivalent to that obtained with current injection (Figure 1G) in response to 1-ms pulses of 470-nm light in neurons expressing CH2-EYFP, as indicated by fluorescence with 488-nm light. Light did not elicit either inward currents or depolarization in neurons that did not express CH2-EYFP within the same animals.

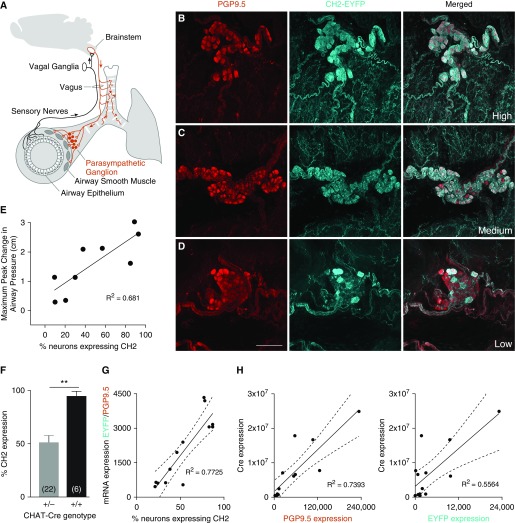

Whole-Mount Fluorescence Microscopy of Tracheal Parasympathetic Nerves Reveals Variable Expression of CH2 in Heterozygous CHAT-CH2 Mice

Overlap of fluorescent labeling for EYFP and PGP9.5 confirmed that CH2 was expressed within parasympathetic neurons. However, high variability in the proportion of postganglionic parasympathetic neurons expressing CH2 was observed between breeding pairs and even within litters (Figures 2B–2D, Table E1). A linear relationship (R2 = 0.681, P < 0.001) was found between the percentage of nerves expressing CH2 and the maximum light-induced increase in airway peak pressure (Figure 2E). This relationship demonstrates that observed increases in airway pressure are the direct result of activation of CH2-expressing airway parasympathetic neurons.

Figure 2.

Light-induced bronchoconstriction is proportional to airway CH2 expression. (A) Diagram of airway innervation showing pathway of reflex bronchoconstriction. (B–D) Parasympathetic ganglia from mice expressing CH2 in 96% (B), 84% (C), and 16% (D) of postganglionic parasympathetic airway neurons. Scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Linear relationship between the percentage of CH2 expression in airway postganglionic parasympathetic neurons and the maximum increase in airway peak pressure with 30 seconds of light in the presence of physostigmine (P = 0.0062). (F) Mice with two copies of Cre driven by the choline acetyltransferase (CHAT) promoter had higher CH2 expression in the airways (sample size in parentheses; t test, **P = 0.0006). (G) PCR analysis of mRNA expression in lung homogenates represents an alternative method of assessing CH2 expression that is proportional to imaging (P < 0.0001, dashed lines represent 95% confidence interval). (H) PCR analysis of Cre expression in lung homogenates shows a closer relationship to PGP9.5 expression than EYFP expression, indicating that variability in the efficiency of Cre protein rather than variability in expression may be more responsible for CH2 variability overall. PGP9.5 = protein gene product 9.5.

qPCR of Lung Tissue Is a Fast and Reliable Method of Determining CH2 Expression

Although reliable, immunohistochemistry and imaging of every mouse trachea is both an expensive and time-intensive process. To quantify CH2 expression without imaging we extracted RNA from lung tissue in heterozygous mice with variable CH2 expression. Quantification of RNA showed that the ratio of expression of EYFP to the neuronal marker, PGP9.5, in lung tissue correlated well with the percentage of CH2-positive neurons in the tracheas (Figure 2G). Because the submandibular gland is also supplied by parasympathetic innervation, we took samples of this tissue to test whether the level of CH2 expression might be assessed in a nonlethal tissue biopsy. However, the ratio of EYFP to PGP9.5 in these qPCR reactions did not correlate as well to CH2 expression from imaging (Figure E3). To assess whether variability in CH2 expression was due more to a lack of Cre efficiency or Cre expression, we correlated PCR results of Cre RNA expression to PGP9.5 and EYFP expression in lung homogenates (Figure 2H). Cre expression was aligned more closely with PGP9.5 compared with EYFP, indicating that Cre is consistently expressed in nerves, but variably efficient at facilitating CH2-EYFP transcription.

Mice Homozygous for CHAT-Cre Have Higher and Less Variable CH2 Expression

In an effort to produce animals with less variability in CH2 expression, heterozygous mice (genotype CH2+/−CHAT+/−) were bred together, resulting in some mice that were homozygous for both genes (CH2+/+ CHAT+/+). These mice had two copies of the CHAT-Cre gene as well as two copies of floxed CH2. CH2 expression was quantified using imaging, and homozygous mice were found to have a higher percentage of CH2-expressing nerves in parasympathetic ganglia (95 ± 4.4%) than heterozygotes (53 ± 4.8%), P = 0.0006; Figure 2F).

Discussion

Here, we show that it is possible to express CH2 in airway nerves and use these channels to specifically stimulate a single nerve population, in this case parasympathetic nerves, which are anatomically tangled with sensory nerves within the vagus. The method presented in this article is a novel and readily accessible technique for studying the function of airway neurons. Light activation of airway nerves may be achieved through the use of an intense, collimated LED light source after surgical exposure of the trachea. Furthermore, functional effects of that nerve activation can be measured using basic mouse ventilator parameters. Pharmacological enhancement, such as the administration of physostigmine, may be necessary to see the full effects of nerve activation. Expression of endogenous opsins that cause muscle relaxation in response to 430-nm light has been previously demonstrated in airway smooth muscle (16). We did not observe bronchodilation in response to 454-nm light in these experiments, likely because our light source was focused on the trachea, and primarily activated the light-sensitive channels in airway nerves to cause peripheral airway smooth muscle contraction.

Although variability in the effectiveness of Cre within cells is a well-reported phenomenon, we had not anticipated that variability of CH2 expression in CHAT-positive neurons would impact physiological measurements. Many mechanisms may underlie expression variability in Cre-lox systems (17). The likeliest explanation in our system, given that the expression of Cre mRNA was proportional to panneuronal marker PGP9.5 mRNA in lung tissue, is that Cre was being produced in cells, but was unable to efficiently cut the lox sites. Given that variable expression had physiological impact, it will be important to assess expression in animals before using this or any other technique that requires a new Cre-lox mouse line. This will be extremely important to assess in model systems of disease, where changes in transcriptional regulation may affect expression in experimental animals differently than controls. Our finding, that homozygosity for Cre produced higher and less variable expression of CH2, suggests that homozygous mice should be preferentially used in future experiments. If heterozygous mice are used, results from these mice must always be interpreted in the context of expression level, and treatment groups should be large enough to account for a wide range of natural variability. PCR analysis of EYFP/PGP9.5 expression in lungs, as shown in Figure 2F, may be performed to eliminate mice with the lowest expression from analysis.

Studies of airway nerve physiology have described many distinct subpopulations of airway neurons (18, 19), the functions of which are difficult to study using traditional nerve activation techniques. A subset of sensory neurons that produce the neuropeptide substance P has long been implicated in asthma pathophysiology (3, 20), and neurons with receptors for P2X3 have more recently been linked to chronic cough (21, 22). For many of these nerves, mouse lines are already available in which Cre is expressed under the relevant promoter, which means research using our method could advance rapidly. Although our study used only one light-activated protein channel, CH2, it is possible to use multiple channels responding to different wavelengths of light within the same mouse (23). Inhibition of nerves through light-activated chloride channels (such as halorhodopsin) (24) is a variation of this technique that may prove useful. It is also worth noting that robust heart rate decreases were seen in addition to airway pressure increases in response to light. Indeed, the heart rate responses were more sensitive than changes in airway pressure, with no physostigmine necessary to elicit a measurable decrease. Parasympathetic nerves are important regulators of physiologic function for many organs, including the highly complex gastrointestinal system, and continuing to develop techniques to study parasympathetic nerves will advance our ability to interrogate these other systems and increase our understanding of disease beyond the airways.

Work from our laboratory and others has consistently demonstrated changes to nerve architecture (3), neurotransmitter expression (25), and excitability (26) in humans with asthma and in animal models of airway disease. The relevance of these morphological and molecular changes to airway function in vivo has been difficult to assess, as traditional methods, such as vagal nerve stimulation, can nonspecifically activate many different nerve fibers within a nerve bundle. Although this technique of nerve activation would be challenging to apply directly to humans for therapeutic purposes, results from studying the activation of specific nerve subtypes in animal models will give us more precise knowledge of the function of these nerves, and may reveal targets for future pharmacological treatments. We hope this method will prove useful for elucidating the relevant nerve contributions to airway hyperreactivity in many animal models of asthma and airway hyperreactivity, including allergen challenge, viral infection, ozone exposure, organophosphate exposure, and obesity (4–8, 11).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Drs. Matthew Drake, Jane Nie, Brenda Marsh, Becky Proskocil, Quinn Roth-Carter, Stefanie Kaech-Petrie, John Williams, and Will Birdsong for their insights and discussions. Drs. Matthew Drake, Jane Nie, Brenda Marsh, Becky Proskocil, John Williams, Stefanie Kaech-Petrie, and the Advanced Light Microscopy Core (Oregon Health & Science University), Dr. Quinn Roth-Carter (Northwestern University), and Dr. Will Birdsong (University of Michigan) for their many insights and discussions.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01HL124165, R01HL144008, R01HL131525, F30HL145906, and T32HL083808, as well as National Institute of Drug Abuse grants R01DA004523, R01DA008163, R01DA042779, and R21DA048136.

Author Contributions: A.B.P., A.D.F., and D.B.J. designed the study. A.B.P. and S.A. performed the electrophysiology experiments. A.B.P. performed the other experiments. A.B.P. and S.A. analyzed the data. A.B.P. prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. K.M.L. contributed to initial ideas and methods development. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0378MA on January 3, 2020

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Minette PA, Lammers JW, Dixon CM, McCusker MT, Barnes PJ. A muscarinic agonist inhibits reflex bronchoconstriction in normal but not in asthmatic subjects. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1989;67:2461–2465. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.6.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadel JA, Barnes PJ. Autonomic regulation of the airways. Annu Rev Med. 1984;35:451–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.35.020184.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drake MG, Scott GD, Blum ED, Lebold KM, Nie Z, Lee JJ, et al. Eosinophils increase airway sensory nerve density in mice and in human asthma. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaar8477. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aar8477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamko DJ, Yost BL, Gleich GJ, Fryer AD, Jacoby DB. Ovalbumin sensitization changes the inflammatory response to subsequent parainfluenza infection: eosinophils mediate airway hyperresponsiveness, m(2) muscarinic receptor dysfunction, and antiviral effects. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1465–1478. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fryer AD, Jacoby DB. Parainfluenza virus infection damages inhibitory M2 muscarinic receptors on pulmonary parasympathetic nerves in the Guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;102:267–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhein KC, Salituro FG, Ledeboer MW, Fryer AD, Jacoby DB. Dual p38/JNK mitogen activated protein kinase inhibitors prevent ozone-induced airway hyperreactivity in guinea pigs. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fryer AD, Lein PJ, Howard AS, Yost BL, Beckles RA, Jett DA. Mechanisms of organophosphate insecticide–induced airway hyperreactivity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L963–L969. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00343.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nie Z, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD. Hyperinsulinemia potentiates airway responsiveness to parasympathetic nerve stimulation in obese rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51:251–261. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0452OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans CM, Fryer AD, Jacoby DB, Gleich GJ, Costello RW. Pretreatment with antibody to eosinophil major basic protein prevents hyperresponsiveness by protecting neuronal M2 muscarinic receptors in antigen-challenged guinea pigs. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2254–2262. doi: 10.1172/JCI119763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fryer AD, Jacoby DB. Function of pulmonary M2 muscarinic receptors in antigen-challenged guinea pigs is restored by heparin and poly-L-glutamate. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:2292–2298. doi: 10.1172/JCI116116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fryer AD, Wills-Karp M. Dysfunction of M2-muscarinic receptors in pulmonary parasympathetic nerves after antigen challenge. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1991;71:2255–2261. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.6.2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajendran PS, Challis RC, Fowlkes CC, Hanna P, Tompkins JD, Jordan MC, et al. Identification of peripheral neural circuits that regulate heart rate using optogenetic and viral vector strategies. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1944. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09770-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W, Germain RN, Gerner MY. Multiplex, quantitative cellular analysis in large tissue volumes with clearing-enhanced 3D microscopy (Ce3D) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E7321–E7330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708981114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown RH, Walters DM, Greenberg RS, Mitzner W. A method of endotracheal intubation and pulmonary functional assessment for repeated studies in mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1999;87:2362–2365. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yim PD, Gallos G, Perez-Zoghbi JF, Zhang Y, Xu D, Wu A, et al. Airway smooth muscle photorelaxation via opsin receptor activation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2019;316:L82–L93. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00135.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turlo KA, Gallaher SD, Vora R, Laski FA, Iruela-Arispe ML. When Cre-mediated recombination in mice does not result in protein loss. Genetics. 2010;186:959–967. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.121608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang RB, Strochlic DE, Williams EK, Umans BD, Liberles SD. Vagal sensory neuron subtypes that differentially control breathing. Cell. 2015;161:622–633. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tränkner D, Hahne N, Sugino K, Hoon MA, Zuker C. Population of sensory neurons essential for asthmatic hyperreactivity of inflamed airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:11515–11520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411032111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ollerenshaw SL, Jarvis D, Sullivan CE, Woolcock AJ. Substance P immunoreactive nerves in airways from asthmatics and nonasthmatics. Eur Respir J. 1991;4:673–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdulqawi R, Dockry R, Holt K, Layton G, McCarthy BG, Ford AP, et al. P2X3 receptor antagonist (AF-219) in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2015;385:1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morice AH, Kitt MM, Ford AP, Tershakovec AM, Wu W-C, Brindle K, et al. The effect of gefapixant, a P2X3 antagonist, on cough reflex sensitivity: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Eur Respir J. 2019;54:1900439. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00439-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang F, Prigge M, Beyrière F, Tsunoda SP, Mattis J, Yizhar O, et al. Red-shifted optogenetic excitation: a tool for fast neural control derived from Volvox carteri. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:631–633. doi: 10.1038/nn.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang F, Wang LP, Brauner M, Liewald JF, Kay K, Watzke N, et al. Multimodal fast optical interrogation of neural circuitry. Nature. 2007;446:633–639. doi: 10.1038/nature05744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Vries A, Engels F, Henricks PAJ, Leusink-Muis T, McGregor GP, Braun A, et al. Airway hyper-responsiveness in allergic asthma in guinea-pigs is mediated by nerve growth factor via the induction of substance P: a potential role for trkA. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:1192–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lötvall J., Inman M., O’Byrne P. Measurement of airway hyperresponsiveness: new considerations. Throax. 1998;53:419–424. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.5.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.