Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a lung disease with limited therapeutic options that is characterized by pathological fibroblast activation and aberrant lung remodeling with scar formation. YAP (Yes-associated protein) is a transcriptional coactivator that mediates mechanical and biochemical signals controlling fibroblast activation. In this study, we developed a high-throughput small-molecule screen for YAP inhibitors in primary human lung fibroblasts. Multiple HMG-CoA (hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A) reductase inhibitors (statins) were found to inhibit YAP nuclear localization via induction of YAP phosphorylation, cytoplasmic retention, and degradation. We further show that the mevalonate pathway regulates YAP activation, and that simvastatin treatment reduces fibrosis markers in activated human lung fibroblasts and in the bleomycin mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis. Finally, we show that simvastatin modulates YAP in vivo in mouse lung fibroblasts. Our results highlight the potential of small-molecule screens for YAP inhibitors and provide a mechanism for the antifibrotic activity of statins in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Keywords: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Hippo pathway, drug screening, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, fibroblast

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is an incurable disease that leads to progressive respiratory decline with high morbidity and mortality (1). Although two drugs, nintedanib (2) and pirfenidone (3), are now approved for IPF treatment, they only slow disease progression, and there are no available treatments that stop or reverse the development of lung fibrosis.

Aberrant or overexuberant wound-healing responses to repetitive injury are believed to underlie the pathogenesis of IPF (4). Fibroblasts are the principal effector cells in IPF, being responsible for the synthesis of excess extracellular matrix components (5). A key feature of IPF fibroblasts is their differentiation into myofibroblasts, characterized by a contractile phenotype typified by the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and increased collagen production (6). Myofibroblast differentiation is directed by both biochemical and biomechanical signals, such as TGF-β (transforming growth factor-β) (7) and stiffening of the extracellular matrix in fibrosis (8). Given their central role in fibrogenesis, blocking fibroblast activation and differentiation is a promising therapeutic strategy for fibrotic diseases (9).

YAP (Yes-associated protein) and TAZ (transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif) are transcriptional coactivators that when active translocate to the nucleus and induce the expression of a wide range of genes, controlling cell proliferation, survival, and migration (10). YAP/TAZ are major mediators of mechanical signals in fibroblasts and have been shown to mediate pivotal fibrotic pathways such as WNT and TGF-β (11–13). Fibroblasts in human IPF lungs have increased YAP/TAZ localization in their nuclei, and YAP/TAZ knockdown attenuates profibrotic fibroblast functions in vitro (14). In addition, activation of YAP or TAZ in fibroblasts was found to be sufficient to drive lung fibrosis in a murine adoptive cell transfer model (14). In murine kidney and liver models, inhibition of YAP/TAZ was shown to prevent fibroblast or hepatic stellate cell activation and to reduce fibrogenesis (15, 16). Recently, DRD1 (dopamine receptor 1) agonism was shown to selectively inhibit YAP/TAZ in fibroblasts, effectively reversing fibroblast activation and decreasing lung and liver fibrosis markers in mouse models (17). In sum, YAP/TAZ inhibition has been shown to block profibrotic lung fibroblast activity and therefore may be an attractive antifibrotic therapeutic strategy.

In this study, we developed a high-throughput small-molecule screen for YAP inhibitors in human lung fibroblasts (HLFs) with the purpose of identifying new therapies for IPF. Our primary screening identified multiple small-molecule families that inhibit YAP, including the HMG-CoA (hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A) reductase inhibitors (statins). Statins target the sterol biosynthetic pathway and are widely used to lower blood cholesterol levels and prevent heart disease and strokes (18). Previous studies in other cell systems showed that statins regulate YAP through the mevalonate pathway (19–21), but did not assess this mechanism in fibrosis. Interestingly, clinical data from patients with interstitial lung disease and a retrospective analysis of IPF clinical trials showed better outcomes and reduced mortality among statin users (22–24). Here, we investigated the mechanisms by which statins inhibit YAP in primary HLFs, including induction of YAP phosphorylation, degradation, and nuclear exclusion. We further show that statins inhibit YAP independently of Hippo signaling through targeting of the mevalonate pathway, and prevent profibrotic fibroblast differentiation in vitro. Finally, we show for the first time that simvastatin modulates YAP localization in mouse lung fibroblasts in vivo and attenuates established lung fibrosis in the bleomycin mouse model of IPF. These results confirm the effectiveness of our screening to identify novel YAP inhibitors for the treatment of lung fibrosis, and provide mechanistic proof of concept for future studies examining the effectiveness of statins for treatment of IPF.

Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (25).

Methods

HLF Culture

Primary HLFs were collected through the MGH Fibrosis Translational Research program from deidentified discarded excess tissue from clinically indicated surgical lung resections or lung transplant explants. Cells from subjects with IPF or healthy control donors were expanded and frozen at passage 3. Cells from a healthy control donor (699) were plated at passage 5 for the compound screen. Unless otherwise stated, experiments were conducted using fibroblasts from donor 699. Cells were routinely grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Lonza) supplemented with 10% FBS (Lonza), 2 mM L-glutamine (Lonza), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Lonza) in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

High-Throughput Drug Screening

The small-molecule screen and subsequent high-throughput validation experiments were conducted at the ICCB-Longwood Screening Facility at Harvard Medical School. HLFs were seeded on 384-well, clear-bottom, black microplates (3764; Corning) at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2 using a Multidrop Combi Reagent Dispenser (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 2 days in culture, the wells were washed twice with serum-free medium, leaving a residual 10 μl medium each time, and filled to a final volume of 30 μl. Then, 100-nl compounds diluted in DMSO were added to each well by pin transfer using a Seiko Compound Transfer Robot (V&P Scientific). Negative (DMSO) and positive (cytochalasin D) controls were added using a multichannel pipette. Plates were reincubated overnight (16–18 h) and then fixed and stained for YAP detection and subcellular quantification (see the data supplement). Plates were monitored for cell density, percentage of nuclear YAP+ cells in control wells, and z-scores (26), and rescreened if deemed necessary. Hits were defined as compounds with a score higher than 21.26, corresponding to a 1% false-discovery rate.

A total of 13,232 small molecules from the ICCB Known Bioactives and Academic collections were screened in duplicate. Most libraries screened were plated at 10 mM, for a final screening concentration of 33 μM. Specific library information and compound concentrations can be found on the ICCB website (https://iccb.med.harvard.edu/compound-libraries).

Additional Methods

Additional experimental details and methods are provided in the data supplement.

Results

High-Throughput Small-Molecule Screen for YAP Inhibitors Identifies Statins

We designed a high-throughput compound screen for YAP inhibitors in fibroblasts (Figure 1A). We measured YAP activity by immunostaining the endogenous protein and quantifying its nucleocytoplasmic ratio, as active YAP is found in the nucleus and is inactivated by cytoplasmic translocation (27). Low-passage primary HLFs were grown for 2 days on plastic 384-well plates in the presence of 10% FBS in subconfluent conditions. Under these conditions, HLFs display a predominantly nuclear YAP expression (Figure 1B). We used an automated custom nucleocytoplasmic translocation analysis module to detect YAP activation. The actin polymerization inhibitor cytochalasin D served as a positive control, as this drug alters cell morphology by disrupting the cytoskeleton and rapidly displaces YAP from the nucleus (Figure 1B). Importantly, this effect is fully reversible and not due to toxicity, as HLFs quickly recover their shape when the drug is washed out, accompanied by the regaining of nuclear YAP.

Figure 1.

Several statins were identified in a high-throughput screen for YAP (Yes-associated protein) inhibitors in primary human lung fibroblasts (HLFs). (A) Schematic representation of the high-throughput, small-molecule screen. (B) HLFs were stained with YAP (top, green) and phalloidin and DAPI (bottom, red and blue, respectively) to label actin and the nucleus. YAP is nuclear in subconfluent cultures treated with vehicle (DMSO) and is rapidly displaced by cytochalasin D treatment (2 μM, 2 h), used here as control, which disrupts the actin cytoskeleton and decreases cell size. These effects are reversible by washing out the drug, which restores cell morphology and returns YAP to the nucleus after 4 hours. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Scoring of a screen library plate. The percentage of cells displaying nuclear YAP was calculated for each well and the two replicate values were plotted. All compounds (green) were diluted in DMSO, which was added as a negative control (blue). Cytochalasin D was used as a positive control (red) and decreased the percentage of nuclear YAP+ cells. A “score” for each compound was calculated by measuring the distance between each dot and the 75th percentile of the plate, and penalizing replicate variability and low cell number. (D) Screen results by library plate, depicting statins identified as hits. The yellow line marks the 1% false-discovery rate threshold (score = 21.26). (E) Distribution of the main activities of annotated hits (corresponding to 86.4% of unique compounds) in two levels of granularity, including the major target classes and their respective ratio within the hit set (left) and the percentage of the target subclasses for each major class (right). GPCR = G protein–coupled receptor.

Using this system, we screened 13,232 compounds from the Known Bioactives collection and the academic collection at the ICCB-Longwood Screening Facility at Harvard Medical School. Duplicate plates with HLFs were treated overnight (16–18 h) with each drug at 33 μM in serum-free media. Lower concentrations were used for specific library plates containing compounds known to induce toxicity at high concentrations. Although a short incubation time might optimally identify direct YAP modulators, we chose a longer incubation period to identify nontoxic compounds that result in prolonged YAP inhibition, a more attractive profile for antifibrotic therapy. Cells with a nuclear/cytoplasmic YAP ratio > 1 were considered “nuclear YAP+ cells.” The percentage of nuclear YAP+ cells was high in negative control (DMSO) and low in positive control (cytochalasin D) wells (Figure 1C). We observed a good correlation between the two replicates for each library plate (mean correlation of 0.84 with an SD of 0.06) and good separation between experimental wells and controls.

We developed a scoring method to consolidate a compound’s effect into a single standardized value. This value can be compared across plates, so a drug that elicits equal YAP translocation into the cytoplasm in both replicates with minimum toxicity will have a high score. Using this scoring system, 2,099 of the 13,232 compounds screened had a score higher than 21.26, corresponding to a 1% false-discovery rate (Figure 1D). Analysis of chemical structures revealed that the 2,099 hits mapped into 1,522 unique compounds. Using the ChEMBL 25 database, we were able to annotate >86% of the compounds and stratify them according to their main activity (Figure 1E). Almost half of the annotated hit targets were enzymes, 66.9% of which were kinases. Class A G protein–coupled receptors comprised the second largest target group, being targeted by almost 30% of the compounds. Among the hits we identified seven statins: simvastatin, cerivastatin, mevastatin, lovastatin, fluvastatin, pitavastatin, and atorvastatin (Figure 1D). Notably, these seven statins were identified as hits multiple times independently because of library redundancy.

We confirmed our primary screen findings by testing statins on primary HLFs derived from multiple donors. We performed dose–response experiments with simvastatin and mevastatin on five HLF lines derived from patients with IPF and seven HLF lines from healthy donors (including the one used in the screen, N 699) (Figure 2). Overall, both statins elicited a concentration-dependent decrease of nuclear YAP, with simvastatin being more potent in some cell lines (Figure 2A). Both IPF and normal HLF lines responded to statin treatment similarly. Simvastatin at the highest concentration (33 μM) decreased cell numbers, so all subsequent treatments were performed at a maximum of 10 μM to avoid this effect. We observed that at this concentration, the effects of simvastatin treatment on YAP localization were reversible, as YAP staining was again predominantly nuclear 2 hours after the drug was washed out (Figure E1 in the data supplement).

Figure 2.

Statins induce YAP nuclear exclusion in HLFs from multiple normal donors and patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in a dose-dependent manner. Dose–response curves of two statins identified in the primary screening: simvastatin (Sim) (pink, circles) and mevastatin (Mev) (blue, triangles). Primary HLFs from different donors were treated overnight (16–18 h) with statins in serum-free medium. (A and B) The nuclear/cytoplasmic YAP ratio (A) and cell number (B) were calculated for three wells per concentration. Approximately 1,000–2,000 cells were automatically scored per well; data points represent averages from individual wells. HLFs from different donors are labeled “N” for normal and “F” for IPF-derived.

Statins Inhibit YAP by Inducing Its Nuclear Exclusion, Phosphorylation, and Degradation Independently of Hippo Signaling

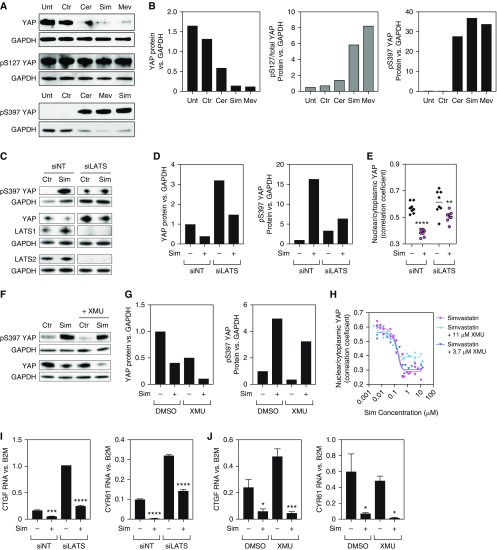

Next, we investigated YAP protein levels and phosphorylation status upon statin treatment. We observed decreased YAP levels in HLFs treated with simvastatin, mevastatin, or cerivastatin (Figures 3A and 3B). We detected no differences in gene expression (Figure E2A), suggesting that YAP levels are post-translationally regulated by statins. Accordingly, statins induced a marked increase in the phosphorylation of serine 397 (pS397) (Figures 3A and 3B), which marks YAP for proteasomal degradation (28). Levels of serine 127 (S127) phosphorylation remained constant, whereas total YAP decreased, resulting in an increased pS127/total YAP ratio (Figures 3A and 3B). Phosphorylation of S127 promotes binding of YAP to 14-3-3 proteins and leads to cytoplasmic sequestration (29). Overall, these data indicate that statins promote YAP phosphorylation, resulting in its cytoplasmic sequestration and degradation, which together lead to YAP exclusion from the nucleus. We also investigated the effects of statin treatment on the YAP paralogue, TAZ. Similar to what was observed with YAP, TAZ mRNA levels were not significantly altered by statin treatment (Figure E2A). Treatment of HLFs with simvastatin reduced TAZ protein levels and increased the ratio of serine 89 phosphorylation (equivalent to S127 in YAP), consistent with TAZ cytoplasmic sequestration (Figures E2B and E2C). These results suggest that statins may similarly regulate YAP and TAZ.

Figure 3.

Statins inhibit YAP by inducing its nuclear exclusion, phosphorylation, and degradation independently of the Hippo pathway. (A and B) Representative Western blots (A) for total and phosphorylated YAP and the respective quantifications (B). Overnight treatment with cerivastatin (Cer), Sim, or Mev elicited a decrease in total YAP levels and induced S397 phosphorylation, which targets YAP for proteasomal degradation. Phosphorylation of S127 promotes YAP cytoplasmic sequestration. Levels of p127-YAP were not altered by statin treatment, resulting in a higher ratio of phosphorylated/total protein, consistent with YAP nuclear exclusion. (C–E) Knockdown of the Hippo pathway effector kinases LATS1/2 by siRNA (siLATS) does not fully prevent the effects of Sim in YAP phosphorylation and degradation (C and D) and intracellular localization (E). siNT = nontargeting siRNA control. Approximately 30–100 cells were automatically scored per well. **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001 for Sim compared with controls. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. Data represent averages from individual wells + median. (F and G) Pharmacological inhibition of Hippo signaling with the MST1/2 inhibitor XMU-MP-1 does not prevent the effects of Sim in YAP phosphorylation and degradation. (H) Dose–response curves of HLFs treated with Sim alone (pink, circles) or in combination with 3.7 μM (purple, inverted triangles) or 11 μM (blue, triangles) of the MST1/2 inhibitor XMU-MP-1. The nuclear/cytoplasmic YAP ratio was calculated for three wells per concentration. Approximately 400–1,600 cells were automatically scored per well. Data points represent averages from individual wells. (I and J) Sim decreases expression of direct YAP targets CTGF and CYR61 independently of the Hippo pathway. Neither siRNA-mediated LATS1/2 knockdown (I) nor pharmacological MST1/2 inhibition with XMU-MP-1 (J) prevented the reduction in YAP target gene expression in HLFs treated with Sim. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 for Sim compared with controls. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. CTGF = connective tissue growth factor; CYR61 = cysteine rich angiogenic inducer 61; Ctr = control; MST1/2 = mammalian Ste20-like kinases 1/2; Unt = untreated; XMU = XMU-MP-1.

The canonical YAP regulators from the Hippo pathway are MST1/2 (mammalian Ste20-like kinases 1/2) and LATS1/2 (large tumor suppressor 1/2) (10). When the Hippo pathway is activated, MST1/2 phosphorylate LATS1/2, which inactivate YAP by phosphorylating it on five serine residues, including S127 and S397 (29). To investigate whether the Hippo pathway is required for YAP phosphorylation and inactivation downstream of statins, we treated HLFs with siRNAs against LATS1 and LATS2. We observed increased YAP protein levels in HLFs treated with siRNA against LATS1/2, consistent with repression of Hippo signaling, but we still detected a decrease in YAP protein with simvastatin treatment (Figures 3C and 3D). Simvastatin was also able to increase the ratio of YAP S397 phosphorylation (Figures 3C and 3D) and to decrease the nuclear/cytoplasmic YAP ratio (Figure 3D), even after LATS1/2 knockdown.

Similarly, treatment of HLFs with the MST1/2 inhibitor XMU-MP-1 did not prevent YAP phosphorylation and degradation upon simvastatin treatment (Figures 3F and 3G). Dose–response curves of HLFs cotreated with simvastatin and XMU-MP-1 show that inhibiting the Hippo pathway did not fully prevent the decrease in the nuclear/cytoplasmic YAP ratio elicited by simvastatin (Figure 3H). In addition, simvastatin decreased the expression of YAP target genes CTGF (connective tissue growth factor) and CYR61 (cysteine rich angiogenic inducer 61) (Figures 3I and 3J), which could not be prevented by LATS1/2 knockdown (Figure 3I) or MST1/2 inhibition (Figure 3J). Together, these data indicate that statin modulation of YAP phosphorylation and localization in HLFs does not require MST1/2 or LATS1/2 activity and is independent of the Hippo pathway.

The Mevalonate Pathway Controls YAP Localization and Activity

Statins are best known for their cholesterol-lowering effects through targeting of HMGCR (HMG-CoA reductase) (30). This enzyme catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the mevalonate pathway, which is responsible for the synthesis of cholesterol and other terpenoids (31). We investigated whether knocking down other proteins in the mevalonate pathway leads to YAP inactivation (Figure 4A). We observed a marked exclusion of YAP from the nucleus of HLFs transfected with siRNAs against HMGCS1 (HMG-CoA Synthase 1), the enzyme that synthesizes HMG-CoA (Figures 4B and 4C). Similar results were observed upon silencing of the downstream effectors in the mevalonate pathway, FDPS (Farnesyl Diphosphate Synthase) and GGPS1 (Geranylgeranyl Diphosphate Synthase 1), which regulate protein prenylation (Figures 4B and 4C). We further measured effects on the RNA expression of two YAP targets, CTGF and CYR61. In HLFs treated with two individual siRNA duplexes targeting HMGCS1, we observed a decrease in the CTGF and CYR61 RNA levels, comparable to levels observed with YAP silencing (Figure 4D). Taken together, these data indicate that the mevalonate pathway controls YAP activity in HLFs.

Figure 4.

The mevalonate pathway controls YAP localization and activity. (A) Simplified schematic of the mevalonate pathway, including the rate-limiting step inhibited by statins. The dotted arrow represents different steps involving multiple intermediates. Enzymes targeted in this study are depicted in red. (B) Representative images of HLFs treated for 72 hours with siRNAs against different enzymes in the mevalonate pathway and stained with DAPI (blue) and antibodies for YAP (green). Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Quantification of the nuclear/cytoplasmic YAP ratio (represented in log2 values) shows significant YAP nuclear exclusion in HLFs treated with siRNAs against HMGCS1, FDPS, and GGPS1. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with siNT using a two-tailed t test. Approximately 1,200–2,100 cells were automatically scored per well. Data points represent averages from individual wells. Data represent mean ± SD. (D) Quantitative PCR analysis of the levels of two YAP target genes, CTGF and CYR61. HLFs treated with siRNAs against YAP or with two distinct siRNA duplexes targeting HMGCS1 show decreased levels of CTGF and CYR61. ****P < 0.0001 compared with siNT using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Data represent mean ± SD. FDPS = farnesyl diphosphate synthase; GGPP = geranylgeranyl-pyrophosphate; GGPS1 = geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase 1; HMGCR = HMG-CoA reductase; HMGCS1 = HMG-CoA Synthase 1.

Protein Prenylation with Geranylgeranyl Pyrophosphate Is Essential for Actin Fiber Formation and YAP Activation

The mevalonate pathway has been shown to control YAP in other cell types through GGPP (Geranylgeranyl Pyrophosphate)-mediated RhoA activation and actin fiber polymerization (19–21) (Figure 5A). Consistent with this, we observed that disruption of the actin cytoskeleton in HLFs by cytochalasin D displaced YAP from the nucleus (Figures 1B and 1C), and that knockdown of FDPS or GGPPS1, two enzymes responsible for GGPP generation, reduced nuclear YAP in HLFs (Figures 4B and 4C). We thus investigated whether YAP inactivation by statins could be reversed by addition of GGPP to the culture media. We treated HLFs with cerivastatin, simvastatin, or mevastatin for 2 days and supplemented the medium with GGPP or vehicle control (ethanol). These experiments were conducted in the presence of the profibrotic cytokine TGF-β (7), which promotes actin fiber formation, to test statins in fibrosis-relevant activated fibroblasts and to better display differences in actin fiber dynamics (Figure 5). Statin treatment was associated with decreased cell numbers (Figure E3A), probably due to inhibition of proproliferative YAP/TAZ signaling (27). All three statins significantly decreased actin intensity and the number of actin fibers per cell (Figures 5B and 5C). We observed similar results in the absence of TGF-β (Figure E3). In addition, statin treatment significantly prevented α-SMA fiber formation, a hallmark of profibrotic myofibroblast differentiation (6) (Figure 5C). Of note, mevastatin was less potent than simvastatin or cerivastatin at reducing both actin fiber formation and YAP nuclear localization, which supports the interdependency of both phenotypes. GGPP supplementation completely abrogated the effects of statins on the cytoskeleton and YAP localization (Figures 5B and 5C). Furthermore, GGPP supplementation prevented the decrease in CTGF and CYR61 expression elicited by simvastatin (Figure 5D). The expression of these YAP targets was similarly reduced by treating HLFs with GGTI-298, an inhibitor of GGTase-I, which catalyzes the transference of GGPP to target proteins such as RhoA (Figures 5A and 5D) (32, 33). In contrast, we observed no differences in HLFs treated with an inhibitor of FTase, which prenylates other proteins by transferring Farnesyl-PP (data not shown). We next tested the antifibrotic potential of statins in more detail. In addition to decreasing CTGF and CYR61 expression (Figure 5D), we observed that simvastatin effectively reduced the expression of the profibrotic genes ACTA2 and COL1A1 in TGF-β–treated HLFs (Figure E4).

Figure 5.

Statins modulate YAP localization and activity through the GGPP/Rho/actin signaling axis. (A) Schematic depicting the proposed regulation of YAP through the mevalonate pathway (box). The dotted arrow represents different steps involving multiple intermediates. Enzymes are depicted in red. Statins target the mevalonate pathway by inhibiting the rate-limiting enzyme HMGCR. The mevalonate pathway produces GGPP, which is transferred to Rho proteins by the prenyltransferase GGTase-I. This step can be pharmacologically blocked by GGTI-298. Prenylated RhoA associates with the cell membrane and becomes activated, promoting actin fiber formation. Filamentous actin inhibits YAP phosphorylation, preventing its cytoplasmic sequestration (S127-pYAP) and degradation (S397-pYAP). These effects can be reverted by reducing GGPP formation (e.g., by adding statins or knocking down enzymes in the pathway) or blocking GGPP attachment to Rho proteins (e.g., by adding GGTI-298). TF = transcription factor. (B and C) HLFs were treated with profibrotic TGF-β, statins, 5 μM GGPP, and vehicle controls in serum-free media for 48 hours, fixed, and stained for YAP, actin, or α-SMA (α-smooth muscle actin) fluorescent imaging. (B) Representative images of YAP (top) and actin (bottom) staining. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Quantification of different imaging parameters. The percentage of nuclear YAP+ cells decreased with statin treatment and was rescued by GGPP supplementation (striped bars). Actin fluorescence intensity and actin and α-SMA fiber numbers were significantly reduced by statin treatment, but not in wells supplemented with GGPP. **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001 compared with the respective controls: Unt (black) for Cer (blue), and DMSO (Ctr, gray) for Sim (green) and Mev (orange); one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Approximately 300–1,500 cells were automatically scored per well. Data represent mean ± SD of the averages of eight independent wells. (D) HLFs were treated with profibrotic TGF-β and different drug combinations in serum-free media for 24 hours (Sim, 1 μM GGPP or 10 μM GGTI-298). Both Sim and GGTI-298 treatment decreased the expression of YAP target genes CTGF and CYR61. GGPP supplementation reversed the effects of Sim, suggesting that statins modulate YAP activity through GGPP/Rho signaling. ****P < 0.0001 compared with control; one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. GGTI = GGTI-298; ns = not significant; TGF-β = transforming growth factor-β.

Taken together, these data indicate that statins are able to inactivate YAP in HLFs undergoing fibrotic differentiation through modulation of the mevalonate pathway, reduction of GGPP synthesis and GGPP-mediated RhoA activation, and inhibition of actin fiber formation.

Simvastatin Reduces Lung Collagen Deposition in a Bleomycin Mouse Model of Pulmonary Fibrosis

We tested the effects of simvastatin in vivo using the bleomycin mouse model of IPF. Prior studies have demonstrated that different statins successfully prevent fibrosis development in this model when given concurrently with bleomycin administration (34–37). In the bleomycin model, the first 7 days after injury are characterized by an acute inflammatory phase, with a fibrotic phase primarily occurring after day 7 (38). Fibrogenesis is accompanied by the recruitment of fibroblasts to the sites of lung injury, where they differentiate into myofibroblasts and secrete extracellular matrix components and other profibrotic factors, establishing fibrosis around Day 14 (38–40). Thus, the reported benefits of statins given at the time of initial injury in prior studies could be due to their antiinflammatory properties, rather than antifibrotic inactivation of fibroblasts (41). To determine whether statins could inhibit fibroblast activity and ameliorate fibrosis in established disease, we used a therapeutic regimen, starting simvastatin treatment after fibrosis was established at Day 14 after bleomycin treatment (Figure 6A). Bleomycin treatment effectively induced fibrotic lesions and promoted lung collagen deposition, as measured by Masson’s trichrome staining and the hydroxyproline assay (Figures 6B and 6C). Notably, mice treated daily with simvastatin for 2 weeks starting on Day 14 after bleomycin treatment displayed reduced fibrotic lung remodeling and a significant decrease in lung collagen content compared with mice that received vehicle control solution (Figure 6B). These results indicate that statins were able to attenuate established lung fibrosis in this model.

Figure 6.

Sim attenuates established fibrosis in the bleomycin mouse model. (A) Diagram of the in vivo therapeutic experiment. Mice were injected intratracheally with 1 U/kg bleomycin to induce lung fibrosis, or with PBS (vehicle) control. After 2 weeks, when fibrosis was established, the mice were treated daily with Sim (20 mg/kg/d) or vehicle control. The mice were killed after 2 weeks and the whole lung was collected for collagen quantification or immunohistochemistry staining. (B) Representative 5× mouse lung sections stained with Masson’s trichrome, showing decreased fibrotic lesions and collagen fibers after Sim treatment. (C) Total lung collagen content was quantified with the hydroxyproline assay. Compared with PBS (sham), bleomycin-treated mice displayed an increase in hydroxyproline content per lung, which was significantly reduced by simvastatin treatment. Data were pooled from three independent experiments. **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001 compared with control bleomycin using one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. Data represent mean ± SD.

YAP Is Modulated by Simvastatin In Vivo

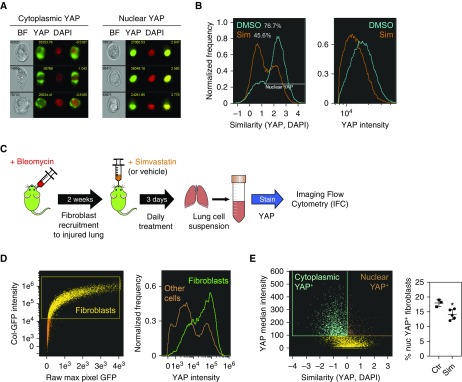

We showed that statins effectively modulated YAP in fibroblasts in vitro and were able to reduce collagen content in the lungs of mice after the onset of fibrosis. However, it was unclear whether statins could target fibroblasts in vivo. To address this issue, we used imaging flow cytometry (IFC) to quantify intracellular nucleocytoplasmic translocation events in immunophenotypically defined cell populations (42, 43). We first assessed the detection of YAP translocation in HLF cultures by IFC. Multiple events of “nuclear” or “cytoplasmic” YAP staining could be detected in HLFs costained for YAP and nuclei (with DAPI) (Figure 7A). To quantify the relative localization of YAP within the cell (nucleus or cytoplasm), we used the similarity score, which compares the fluorescence profiles of the protein of interest (YAP) and the nuclear dye DAPI (44). If YAP is nuclear, the similarity score is high, whereas if YAP is in the cytoplasm, the similarity is low. HLFs treated with simvastatin displayed a marked shift in the similarity score, with only 45.6% of cells displaying a predominantly “nuclear” YAP staining pattern, compared with 76.7% in the control group (Figure 7B). This is consistent with our previous observations using conventional imaging (Figures 2A and 5B). Moreover, we detected a decrease in YAP intensity in cells treated with simvastatin (Figure 7B), consistent with our previous observation that statins promote YAP degradation (Figure 3A).

Figure 7.

YAP localization is modulated by Sim in vitro and in vivo. (A) Representative imaging flow cytometry (IFC) images of HLFs stained with YAP (green) and DAPI (red) exhibiting cytoplasmic or nuclear YAP localization. BF = brightfield. (B) IFC analysis of HLFs treated overnight with Sim (orange) or vehicle control (DMSO, blue). Sim treatment elicited a shift from nuclear to cytoplasmic YAP staining, measured by similarity (left) and a decrease in YAP intensity (right). (C) Diagram of the experiment to measure YAP localization in fibroblasts in vivo. Mice were injected intratracheally with 1 U/kg bleomycin to induce lung injury and fibroblast recruitment. After 2 weeks, they were treated with Sim (20 mg/kg/d) or vehicle control for 3 days, and then killed. Lungs were digested to generate single-cell suspensions, fixed, and stained for YAP and DAPI IFC analysis. (D) IFC analysis of Col-GFP (Col1A1-GFP) reporter mouse lung cells. A population of cells expressing high levels of Col-GFP was defined as “fibroblasts” (left). Fibroblasts (right panel, green) were found to express high levels of YAP compared with other lung cells (right panel, brown). (E) The percentage of nuclear YAP+ cells within the fibroblast population defined in D was calculated by plotting the YAP median pixel intensity against similarity (YAP, DAPI) (left). YAP-expressing fibroblasts were classified as “cytoplasmic YAP+” (blue) or “nuclear YAP+” (brown) based on similarity (YAP and DAPI) levels. Within the YAP-expressing population, the proportion of nuclear YAP+ fibroblasts was significantly decreased by Sim treatment (right). *P < 0.05 using a two-tailed t test.

Next, we looked at YAP expression in vivo. Because of the lack of broad fibroblast markers (45), we focused on lung cells expressing high levels of collagen, as this population is highly enriched in fibroblasts (46). We used Col-GFP (Col1A1-GFP) reporter mice to identify tissue-resident fibroblasts, as previously described (46–48). We confirmed that lung immune cells (CD45+), epithelial cells (CD45−, Epcam+, and CD31−) and endothelial cells (CD45−, Epcam−, and CD31+) expressed very low GFP levels (Figure E5). We treated Col-GFP mice with bleomycin, waited 2 weeks for fibroblasts to proliferate and migrate to sites of injury in the lung, and then treated the mice with simvastatin (Figure 7C). After 3 days of daily simvastatin or vehicle control treatment, we collected and digested the lungs to generate single-cell suspensions, which we stained for IFC. We observed that YAP intensity was high within the fibroblast population compared with other cell types (Figure 7D). We then examined the distribution of nuclear/cytoplasmic YAP in fibroblasts, focusing on the YAP-expressing population (Figure 7F). Notably, we detected a decrease in the percentage of nuclear YAP+ fibroblasts in the lungs of mice treated with simvastatin. These data support a direct effect of statins on fibroblasts through YAP inhibition in vivo.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and validated a high-throughput, small-molecule screen for YAP modulators in HLFs and identified statins as potent inhibitors. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest small-molecule screen for YAP inhibitors reported to date, comprising >13,000 molecules. Using a luciferase-based assay of TEAD (TEA domain) transcription factor activity, a previous study identified the YAP inhibitor verteporfin in a screen of >3,300 drugs in HEK293 cells (49). This is a straightforward strategy to measure YAP activity, as TEAD transcription factors are major YAP binding partners (50). However, YAP also binds other transcription factors, including p73, RUNXs, SMADs, EGR1, and TBX5, which would not be detected in that assay (51). As an alternative, YAP/TAZ inhibitors have been identified in a small-scale siRNA screen measuring expression of the YAP/TAZ target gene CTGF (52). Although this approach is effective, it is also nonspecific, as many YAP target genes are also regulated by other transcriptional coactivators, such as MRTF (Myocardin-Related Transcription Factor) (53). In our screen, we stained endogenous YAP and quantified nucleo-cytoplasmic translocation. Therefore, our assay directly measures YAP modulation and is not limited to binding to specific transcription factors. A possible caveat is that we are unable to detect the effects of post-translational modifications regulating YAP activity in the nucleus. Two smaller scale-screens have employed a similar strategy to ours and identified statins as YAP/TAZ inhibitors in breast cancer epithelial cells (19, 54).

Statins inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, an enzyme that catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the mevalonate pathway. Here, we show that the mevalonate pathway is a central regulator of YAP activity in HLFs. Knockdown of HMGCS1, which catalyzes the formation of HMG-CoA, induced translocation of YAP into the cytoplasm and a decrease in the expression of YAP target genes CTGF and CYR61. Statins have been shown to regulate YAP in epithelial breast cancer and mesothelioma cell lines by preventing GGPP-mediated RhoA activation and actin fiber formation (20, 21). Consistent with this, we observed a decrease in the nuclear/cytoplasmic YAP ratio upon knockdown of FDPS or GGPS1, which catalyze the formation of GGPP. We also observed decreased actin fiber numbers in the presence of statins and decreased YAP activity. Importantly, these effects could be reversed by GGPP supplementation. We further showed that YAP activity is dependent on geranylgeranylation mediated by GGTase-I, the enzyme that prenylates RhoA using GGPP (32, 33).

Mechanistically, YAP localization and activity can be regulated by phosphorylation in different amino-acid residues. Cerivastatin and simvastatin have been shown to induce S127-YAP phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (19, 20), but not in human pancreatic cancer cells (55). We observed constant levels of S127-phosphorylated YAP in HLFs treated with simvastatin, cerivastatin, or mevastatin. Although we detected an increase in the ratio of S127-phosphorylated to total YAP, this effect was mainly driven by a decrease in total YAP levels. Instead, we observed increased S397 phosphorylation, which marks YAP for degradation through the proteasome (28). Previous studies did not investigate YAP S397 phosphorylation in the presence of statins, but they did not observe reduced YAP levels as we did (19, 20, 55). In agreement with those studies, our data suggest that modulation of YAP phosphorylation, localization, and activity by statins is independent of MST1/2 and LATS1/2 activity.

In our investigation of the antifibrotic potential of statins, we also found that statins prevented HLF activation by TGF-β, reducing the expression of profibrotic genes (CTGF, CYR61, ACTA2, and COL1A1) and preventing actin and α-SMA stress fiber formation. This is consistent with previous research showing that statins reduce profibrotic fibroblast differentiation in the presence of TGF-β (56–60). Prior evidence from mouse models has demonstrated that statins prevent lung fibrosis (34–37, 61). However, these studies did not investigate the ability of statins to reduce established fibrosis, which is a more therapeutically relevant approach for IPF. Indeed, the vast majority of studies in the bleomycin model use a preventive regimen, which does not distinguish between drugs that interfere with the inflammatory response to lung injury and fibrosis (62). Because statins have antiinflammatory properties (41), we designed our animal experiments so that statin treatment only started after the inflammatory phase, so that we could investigate their antifibrotic potential. We initiated simvastatin treatment 14 days after bleomycin challenge, and the mice showed decreased collagen deposition and fibrotic lung remodeling after 2 weeks of daily administration. Our data indicate that, regardless of potential antiinflammatory benefits, simvastatin is effective at reducing established fibrosis in the bleomycin mouse model.

Having established the antifibrotic potential of statins in vivo, we sought to investigate whether this effect involves YAP modulation in fibroblasts, as statins could prevent fibrosis through their cholesterol-lowering properties or by affecting other cell types. To address this issue, we analyzed YAP expression and localization in the lungs of mice treated with bleomycin and simvastatin by IFC. In agreement with our in vitro data, we detected a decrease in the percentage of nuclear YAP+ cells within the fibroblast population in simvastatin-treated mice. This decrease was smaller in magnitude than what we observed in our in vitro experiments. This could be due to differences in drug delivery in vivo or to the fact that not all fibroblasts are equally activated in vivo, even in a fibrotic lung. Recently, YAP/TAZ deletion in Gli+ fibroblasts was shown to reverse fibrosis development in the mouse kidney (63), and fibroblast-selective YAP/TAZ inhibition through DRD1 agonism was able to reverse lung fibrosis and reduce liver fibrosis in mouse models (17). Several other publications have linked the protective effects of different treatments in fibrosis models to YAP/TAZ inhibition (15, 64–69). Here, we present the novel finding that the antifibrotic effects of statins in the lung are mediated at least in part through YAP modulation in lung fibroblasts. Whether statins modulate YAP activity in other in vivo fibrosis models in different organs remains to be investigated.

Statins are commonly prescribed and safe clinical agents, which makes them an attractive treatment option for fibrosis. Indeed, a considerable proportion of patients with IPF are also prescribed statins for comorbidities (70). Some small initial studies found no effect or suggested a detrimental effect of statin use in interstitial lung disease (71–74). However, recent studies using clinical data from patients with interstitial lung disease and a retrospective analysis of IPF clinical trials showed better outcomes and reduced mortality among statin users (22–24). Although these results are promising, prospective studies are needed to definitely assess the effects of statin therapy in IPF. There is also evidence that statins reduce liver fibrosis progression (75, 76). Our work provides a likely antifibrotic mechanism for statins in IPF, contributing to the body of evidence that warrants further studies into the clinical potential of statins in IPF and other fibrotic diseases.

In conclusion, we have developed an effective screening platform for YAP inhibitors in HLFs and validated statins as antifibrotic agents. We are currently testing other hits identified in the screen for their antifibrotic potential.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

This work is dedicated to Andrew Tager, a brilliant scientist, enthusiastic mentor, and true inspiration to all who met him. The authors thank the staff at the ICCB-Longwood Screening Facility and Image and Data Analysis Core at Harvard Medical School for their help with the small-molecule screen and the development of an image analysis custom module, respectively. We also thank the members of the Tager and Medoff labs at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Cedrickx Godbout and Thorsten Schweikardt at Boehringer Ingelheim for medicinal chemistry and compound annotation support.

Footnotes

Supported by Boehringer Ingelheim as part of a collaboration with the Harvard Fibrosis Network (D.M.S, L.P., G.P., P.G., C.K.P., and B.D.M.). B.D.M. is supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL133153.

Author Contributions: D.M.S. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript. L.P. developed the screen analysis and scoring system, analyzed screen data, and generated figures. G.P., P.G., C.K.P., and R.N. performed experiments. K.E.B. and J.J.S. collected and banked the human lung fibroblasts. L.P.H. performed histopathological analysis. Y.L. analyzed screen data and generated a figure. M.B. characterized the screen hit set. P.S., P.N., and D.W. conceived the project and provided intellectual input. A.M.T. conceived the project, provided intellectual input, and supervised the study. B.D.M. provided intellectual input, supervised the study, and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0296OC on January 16, 2020

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, Oster G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:810–816. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, et al. INPULSIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2071–2082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, Fagan EA, Glaspole I, Glassberg MK, et al. ASCEND Study Group. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selman M, King TE, Pardo A American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society; American College of Chest Physicians. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:136–151. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendall RT, Feghali-Bostwick CA. Fibroblasts in fibrosis: novel roles and mediators. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:123. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Prunotto M, Desmoulière A, Varga J, et al. Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: paradigms for connective tissue remodeling. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:1340–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morikawa M, Derynck R, Miyazono K. TGF-β and the TGF-β family: context-dependent roles in cell and tissue physiology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8:a021873. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Booth AJ, Hadley R, Cornett AM, Dreffs AA, Matthes SA, Tsui JL, et al. Acellular normal and fibrotic human lung matrices as a culture system for in vitro investigation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:866–876. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yazdani S, Bansal R, Prakash J. Drug targeting to myofibroblasts: implications for fibrosis and cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;121:101–116. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng Z, Moroishi T, Guan KL. Mechanisms of Hippo pathway regulation. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1–17. doi: 10.1101/gad.274027.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474:179–183. doi: 10.1038/nature10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Totaro A, Panciera T, Piccolo S. YAP/TAZ upstream signals and downstream responses. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:888–899. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0142-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piersma B, Bank RA, Boersema M. Signaling in fibrosis: TGF-β, WNT, and YAP/TAZ converge. Front Med (Lausanne) 2015;2:59. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2015.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu F, Lagares D, Choi KM, Stopfer L, Marinković A, Vrbanac V, et al. Mechanosignaling through YAP and TAZ drives fibroblast activation and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L344–L357. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00300.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szeto SG, Narimatsu M, Lu M, He X, Sidiqi AM, Tolosa MF, et al. YAP/TAZ are mechanoregulators of TGF-β-SMAD signaling and renal fibrogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3117–3128. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mannaerts I, Leite SB, Verhulst S, Claerhout S, Eysackers N, Thoen LF, et al. The Hippo pathway effector YAP controls mouse hepatic stellate cell activation. J Hepatol. 2015;63:679–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haak AJ, Kostallari E, Sicard D, Ligresti G, Choi KM, Caporarello N, et al. Selective YAP/TAZ inhibition in fibroblasts via dopamine receptor D1 agonism reverses fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaau6296. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sirtori CR. The pharmacology of statins. Pharmacol Res. 2014;88:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorrentino G, Ruggeri N, Specchia V, Cordenonsi M, Mano M, Dupont S, et al. Metabolic control of YAP and TAZ by the mevalonate pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:357–366. doi: 10.1038/ncb2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Wu Y, Wang H, Zhang Y, Mei L, Fang X, et al. Interplay of mevalonate and Hippo pathways regulates RHAMM transcription via YAP to modulate breast cancer cell motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E89–E98. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319190110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka K, Osada H, Murakami-Tonami Y, Horio Y, Hida T, Sekido Y. Statin suppresses Hippo pathway-inactivated malignant mesothelioma cells and blocks the YAP/CD44 growth stimulatory axis. Cancer Lett. 2017;385:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreuter M, Bonella F, Maher TM, Costabel U, Spagnolo P, Weycker D, et al. Effect of statins on disease-related outcomes in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2017;72:148–153. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreuter M, Costabel U, Richeldi L, Cottin V, Wijsenbeek M, Bonella F, et al. Statin therapy and outcomes in trials of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiration. 2018;95:317–326. doi: 10.1159/000486286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vedel-Krogh S, Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG. Statin use is associated with reduced mortality in patients with interstitial lung disease. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos DM, Pantano L, Pronzati G, Grasberger P, Probst CK, Black KE, et al. A high-throughput small molecule screen for YAP inhibitors identifies statins as inhibitors of fibroblast activation and pulmonary fibrosis [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A5878. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piccolo S, Dupont S, Cordenonsi M. The biology of YAP/TAZ: Hippo signaling and beyond. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:1287–1312. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao B, Li L, Tumaneng K, Wang CY, Guan KL. A coordinated phosphorylation by Lats and CK1 regulates YAP stability through SCF(beta-TRCP) Genes Dev. 2010;24:72–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.1843810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao B, Wei X, Li W, Udan RS, Yang Q, Kim J, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2747–2761. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Istvan ES, Deisenhofer J. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. Science. 2001;292:1160–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.1059344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friesen JA, Rodwell VW. The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A (HMG-CoA) reductases. Genome Biol. 2004;5:248. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-11-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts PJ, Mitin N, Keller PJ, Chenette EJ, Madigan JP, Currin RO, et al. Rho Family GTPase modification and dependence on CAAX motif-signaled posttranslational modification. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25150–25163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800882200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeda N, Kondo M, Ito S, Ito Y, Shimokata K, Kume H. Role of RhoA inactivation in reduced cell proliferation of human airway smooth muscle by simvastatin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:722–729. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0034OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JW, Rhee CK, Kim TJ, Kim YH, Lee SH, Yoon HK, et al. Effect of pravastatin on bleomycin-induced acute lung injury and pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37:1055–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2010.05431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamblin MJ, Eberlein M, Black K, Hallowell R, Collins S, Chan-Li Y, et al. Lovastatin inhibits low molecular weight hyaluronan induced chemokine expression via LFA-1 and decreases bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Biomed Sci. 2014;10:146–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ou XM, Feng YL, Wen FQ, Huang XY, Xiao J, Wang K, et al. Simvastatin attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Chin Med J (Engl) 2008;121:1821–1829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monceau V, Pasinetti N, Schupp C, Pouzoulet F, Opolon P, Vozenin MC. Modulation of the Rho/ROCK pathway in heart and lung after thorax irradiation reveals targets to improve normal tissue toxicity. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:1395–1404. doi: 10.2174/1389450111009011395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenkins RG, Moore BB, Chambers RC, Eickelberg O, Königshoff M, Kolb M, et al. ATS Assembly on Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: use of animal models for the preclinical assessment of potential therapies for pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56:667–679. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0096ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang K, Rekhter MD, Gordon D, Phan SH. Myofibroblasts and their role in lung collagen gene expression during pulmonary fibrosis: a combined immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization study. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:114–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scotton CJ, Chambers RC. Molecular targets in pulmonary fibrosis: the myofibroblast in focus. Chest. 2007;132:1311–1321. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jain MK, Ridker PM. Anti-inflammatory effects of statins: clinical evidence and basic mechanisms. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:977–987. doi: 10.1038/nrd1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maguire O, Collins C, O’Loughlin K, Miecznikowski J, Minderman H. Quantifying nuclear p65 as a parameter for NF-κB activation: correlation between ImageStream cytometry, microscopy, and Western blot. Cytometry A. 2011;79:461–469. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hritzo MK, Courneya JP, Golding A. Imaging flow cytometry: a method for examining dynamic native FOXO1 localization in human lymphocytes. J Immunol Methods. 2018;454:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.George TC, Fanning SL, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Medeiros RB, Highfill S, Shimizu Y, et al. Quantitative measurement of nuclear translocation events using similarity analysis of multispectral cellular images obtained in flow J Immunol Methods 2006311117–129.[Published erratum appears in J Immunol Methods 344:85.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peyser R, MacDonnell S, Gao Y, Cheng L, Kim Y, Kaplan T, et al. Defining the activated fibroblast population in lung fibrosis using single-cell sequencing. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019;61:74–85. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0313OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hung C, Linn G, Chow YH, Kobayashi A, Mittelsteadt K, Altemeier WA, et al. Role of lung pericytes and resident fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:820–830. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2297OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krempen K, Grotkopp D, Hall K, Bache A, Gillan A, Rippe RA, et al. Far upstream regulatory elements enhance position-independent and uterus-specific expression of the murine alpha1(I) collagen promoter in transgenic mice. Gene Expr. 1999;8:151–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swonger JM, Liu JS, Ivey MJ, Tallquist MD. Genetic tools for identifying and manipulating fibroblasts in the mouse. Differentiation. 2016;92:66–83. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu-Chittenden Y, Huang B, Shim JS, Chen Q, Lee SJ, Anders RA, et al. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1300–1305. doi: 10.1101/gad.192856.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao B, Ye X, Yu J, Li L, Li W, Li S, et al. TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1962–1971. doi: 10.1101/gad.1664408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim MK, Jang JW, Bae SC. DNA binding partners of YAP/TAZ. BMB Rep. 2018;51:126–133. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2018.51.3.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aragona M, Panciera T, Manfrin A, Giulitti S, Michielin F, Elvassore N, et al. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell. 2013;154:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Foster CT, Gualdrini F, Treisman R. Mutual dependence of the MRTF-SRF and YAP-TEAD pathways in cancer-associated fibroblasts is indirect and mediated by cytoskeletal dynamics. Genes Dev. 2017;31:2361–2375. doi: 10.1101/gad.304501.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oku Y, Nishiya N, Shito T, Yamamoto R, Yamamoto Y, Oyama C, et al. Small molecules inhibiting the nuclear localization of YAP/TAZ for chemotherapeutics and chemosensitizers against breast cancers. FEBS Open Bio. 2015;5:542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hao F, Xu Q, Wang J, Yu S, Chang HH, Sinnett-Smith J, et al. Lipophilic statins inhibit YAP nuclear localization, co-activator activity and colony formation in pancreatic cancer cells and prevent the initial stages of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in KrasG12D mice. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watts KL, Sampson EM, Schultz GS, Spiteri MA. Simvastatin inhibits growth factor expression and modulates profibrogenic markers in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:290–300. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0127OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oka H, Ishii H, Iwata A, Kushima H, Toba S, Hashinaga K, et al. Inhibitory effects of pitavastatin on fibrogenic mediator production by human lung fibroblasts. Life Sci. 2013;93:968–974. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watts KL, Spiteri MA. Connective tissue growth factor expression and induction by transforming growth factor-beta is abrogated by simvastatin via a Rho signaling mechanism. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L1323–L1332. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00447.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schaafsma D, McNeill KD, Mutawe MM, Ghavami S, Unruh H, Jacques E, et al. Simvastatin inhibits TGFβ1-induced fibronectin in human airway fibroblasts. Respir Res. 2011;12:113. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Michalik M, Soczek E, Kosińska M, Rak M, Wójcik KA, Lasota S, et al. Lovastatin-induced decrease of intracellular cholesterol level attenuates fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition in bronchial fibroblasts derived from asthmatic patients. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;704:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu B, Ma AQ, Yang L, Dang XM. Atorvastatin attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via suppressing iNOS expression and the CTGF (CCN2)/ERK signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:24476–24491. doi: 10.3390/ijms141224476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moeller A, Ask K, Warburton D, Gauldie J, Kolb M. The bleomycin animal model: a useful tool to investigate treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:362–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liang M, Yu M, Xia R, Song K, Wang J, Luo J, et al. YAP/TAZ deletion in Gli+ cell-derived myofibroblasts attenuates fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3278–3290. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015121354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jin H, Lian N, Zhang F, Bian M, Chen X, Zhang C, et al. Inhibition of YAP signaling contributes to senescence of hepatic stellate cells induced by tetramethylpyrazine. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;96:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toyama T, Looney AP, Baker BM, Stawski L, Haines P, Simms R, et al. Therapeutic targeting of TAZ and YAP by dimethyl fumarate in systemic sclerosis fibrosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao X, Sun J, Su W, Shan H, Zhang B, Wang Y, et al. Melatonin protects against lung fibrosis by regulating the Hippo/YAP pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E1118. doi: 10.3390/ijms19041118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gui Y, Li J, Lu Q, Feng Y, Wang M, He W, et al. Yap/Taz mediates mTORC2-stimulated fibroblast activation and kidney fibrosis. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:16364–16375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu P, Liu Z, Zhao T, Xia F, Gong L, Zheng Z, et al. Lovastatin attenuates angiotensin II induced cardiovascular fibrosis through the suppression of YAP/TAZ signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;512:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.03.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zmajkovicova K, Menyhart K, Bauer Y, Studer R, Renault B, Schnoebelen M, et al. The antifibrotic activity of prostacyclin receptor agonism is mediated through inhibition of YAP/TAZ. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019;60:578–591. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0142OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wuyts WA, Dahlqvist C, Slabbynck H, Schlesser M, Gusbin N, Compere C, et al. Baseline clinical characteristics, comorbidities and prescribed medication in a real-world population of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the PROOF registry. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2018;5:e000331. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2018-000331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nadrous HF, Ryu JH, Douglas WW, Decker PA, Olson EJ. Impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and statins on survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2004;126:438–446. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saad N, Camus P, Suissa S, Ernst P. Statins and the risk of interstitial lung disease: a cohort study. Thorax. 2013;68:361–364. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fernández AB, Karas RH, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Thompson PD. Statins and interstitial lung disease: a systematic review of the literature and of Food and Drug Administration adverse event reports. Chest. 2008;134:824–830. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu JF, Washko GR, Nakahira K, Hatabu H, Patel AS, Fernandez IE, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Statins and pulmonary fibrosis: the potential role of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:547–556. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1574OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Janicko M, Drazilova S, Pella D, Fedacko J, Jarcuska P. Pleiotropic effects of statins in the diseases of the liver. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6201–6213. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i27.6201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Simon TG, King LY, Zheng H, Chung RT. Statin use is associated with a reduced risk of fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2015;62:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.