Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) has become a global public health emergency. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of SARS-induced cytopathic effects (CPEs) is a rational approach for the prevention of SARS, and an understanding of the cellular stress responses induced by viral infection is important for understanding the CPEs. Polyclonal antibodies, which recognized nucleocapsid (N) and membrane (M) proteins, detected viral N and M proteins in virus-infected Vero E6 cells at least 6 and 12 h post-infection (h.p.i.), respectively. Furthermore, detection of DNA ladder and cleaved caspase-3 in the virus-infected cells at 24 h.p.i. indicated that SARS-CoV infection induced apoptotic cell death. Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was significantly up-regulated at 18 h.p.i. in SARS-CoV-infected cells. The downstream targets of p38 MAPK, MAPKAPK-2, HSP-27, CREB, and eIF4E were phosphorylated in virus-infected cells. The p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580, inhibited effectively phosphorylation of HSP-27, CREB, and eIF4E in SARS-CoV-infected cells. However, viral protein synthesis was not affected by treatment of SB203580.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) is the etiological agent responsible for the outbreak of SARS, an extremely severe disease that has spread to many countries throughout the world. In the period from February to June 2003, 32 countries were affected by SARS. SARS-CoV is a positive-strand RNA virus, and its genome is composed of about 29,700 nucleotides. The genomic organization of SARS-CoV is that of a typical coronavirus, and sequentially contains genes encoding polymerase (and polymerase-related proteins), spike, envelope, membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins. Three groups of coronaviruses were known prior to SARS, while phylogenic analysis indicated SARS-CoV to be a member of a fourth group [1], [2]. A vaccine is currently under development and there is no efficacious therapy for SARS.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are signal transducers that respond to extracellular stimulation by cytokines, growth factors, viral infection, and stress, and in turn regulate cell differentiation, proliferation, survival, and apoptosis [3], [4], [5], [6]. In particular, p38 MAPK is strongly activated by stress and inflammatory cytokines. In the case of mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), a prototype coronavirus, virus-infected cells showed induction of p38 MAPK [7]. The SARS-CoV N protein has been reported to be involved in the regulation of cellular signaling pathways [8]. The levels of transcription factors binding to promoter sequences of c-Fos, ATF-2, CREB-1, and Fos B, which are related to AP-1, were increased by expression of N protein. However, there have been no previous reports regarding activation of signaling pathways by infection with SARS-CoV. In addition, no information is available regarding the molecular mechanisms of the cytopathic effects of SARS-CoV-infection. In the present study, we demonstrated that infection of Vero E6 cells by SARS-CoV induced apoptotic cell death and that p38 MAPK and its downstream targets were phosphorylated during viral replication. Understanding the mechanisms of p38 MAPK activation may lead to successful strategies for targeting these molecules in the therapy of SARS.

Materials and methods

Cells and virus. Vero E6 cells were routinely subcultured in 75-cm3 flasks in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 0.2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), and maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. For use in the experiments, the cells were split once they reached 90% confluence and seeded onto 6-well or 24-well tissue culture plate inserts. The culture medium was changed to 2% FBS containing DMEM prior to virus infection. In this study, we used SARS-CoV [9], which was isolated as Frankfurt 1 [10] and kindly provided by Dr. J. Ziebuhr. The seed virus was passaged at least seven times, including one passage in our laboratory. Infection was usually performed with a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 5. The cells were stained with 0.05% crystal violet after fixing with 10% formaldehyde.

Anti-SARS-CoV antibodies. Two peptides, RYRIGNYKLNTD (GenBank Accession No. AAP13571; residues 197–208) and RRVRGGDGKMKE (GenBank Accession No. AAP13814; residues 93–194), corresponding to fragments of the amino acid sequences of membrane (M) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins of SARS-CoV, respectively, were synthesized (Sigma Genosys, Ishikari, Japan). Rabbits were injected with the mixture of peptides (New Drug Development Research Center, Iwamizawa, Japan), and the polyclonal rabbit antisera were used for Western blotting analysis.

Western blotting. After viral infection at an m.o.i. of 5, whole-cell extracts were electrophoresed in 10% and 10–20% gradient polyacrylamide gels, and transferred onto PVDF membrane sheets (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). In this study, we applied two sets of samples to polyacrylamide gels, and the membranes were divided into two sheets after blotting. The following antibodies, obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA), were used in this study at a dilution of 1:1000: rabbit anti-phospho p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), rabbit anti-p38, rabbit anti-phospho MAPKAPK-2 (Thr334), anti-MAPKAPK-2, rabbit anti-phospho HSP-27 (Ser82), mouse anti-HSP-27, mouse anti-phospho CREB (Ser133), rabbit anti-CREB, anti-phospho eIF4E (Ser209), and anti-rabbit eIF4E. Rabbit anti-actin (H-196) (diluted 1:200) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). After 15-h incubation, the membranes were washed with 0.1% TBS–Tween and specific proteins were detected with a ProtoBlot II AP system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), as described previously [11].

DNA fragmentation. A MEBCYTO Apoptosis ladder detection kit (Medical and Biological Laboratories, Nagoya, Japan) was used for detection of DNA fragmentation. After viral infection, cells were lysed with lysis buffer. The cellular DNA was precipitated with ethanol, dried, and resuspended in Tris–EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) containing 100 μg/ml RNase A. The DNA solutions were incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. The DNA was analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and then stained with ethidium bromide.

Results and discussion

Detection of SARS-CoV-specific proteins in virus-infected cells

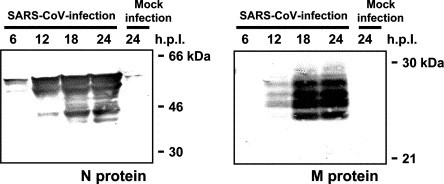

Vero E6 cells were infected with SARS-CoV at an m.o.i. of 5, and Western blotting analysis was performed using polyclonal rabbit serum (see Materials and methods) and cellular extracts obtained at 6, 12, 18, and 24 h.p.i. Nucleocapsid (N) and membrane (M) proteins of SARS-CoV were detected after 6 and 12 h.p.i., respectively (Fig. 1 ). Multiple bands appeared on the Western blots, because the M proteins of coronavirus are glycosylated and the N proteins are phosphorylated in the virally infected cells. These bands were not observed in extracts from cells that were not infected by SARS-CoV, indicating that the polyclonal rabbit sera specifically detected SARS-CoV proteins.

Fig. 1.

Detection of SARS-CoV-specific proteins and activation of caspase-3 in virus-infected cells. Vero E6 cells were infected with SARS-CoV at an m.o.i. of 5, and Western blotting was then performed using proteins obtained at 6, 12, 18, and 24 h.p.i. Polyclonal antibodies against synthetic peptides based on membrane (M) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins were used.

SARS-CoV induces apoptosis in virus-infected cells

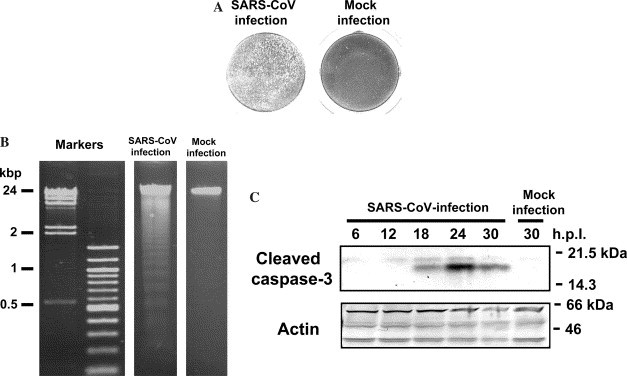

The cytopathic effect (CPE) caused by SARS-CoV is focal with cell rounding [12], and we were clearly able to observe such CPEs at 24 h.p.i. (Fig. 2A ), while mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), a prototype of coronavirus, causes cell-fusion after infection, and MHV infection induces apoptotic cell death in murine 17Cl-1 cells [13]. To confirm whether SARS-CoV-infection induces apoptosis in Vero E6 cells, cellular DNA was extracted from SARS-CoV-infected cells. At 24 h.p.i., DNA fragmentation typical of apoptosis was observed (Fig. 2B). Avian coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) also induces apoptosis in infected Vero cells. Caspase-3, which is one of the main effector caspases and is activated in response to both intracellular and extracellular death signals, was activated by IBV infection [14]. To confirm whether caspase-3 is activated by SARS-CoV-infection, Western blotting analysis was performed using anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody. During apoptosis, caspase precursors are cleaved at Asp-X sites generating a large and a small subunit, which together constitute the active protease; the anti-caspase-3 antibody used in this study can specifically recognize the large fragment of cleaved caspase-3. As shown in Fig. 2C, the cleaved caspase-3 was detected in SARS-CoV-infected Vero E6 cells as a peak at 24 h.p.i. These results indicated that SARS-CoV induces apoptosis in the infected cells.

Fig. 2.

Induction of apoptosis by SARS-CoV-infection. (A) Vero E6 cells were infected with SARS-CoV at an m.o.i. of 5 and stained with 0.05% crystal violet at 24 h.p.i. (B) DNA ladder fragmentation was detected at 24 h.p.i. (C) Western blotting analysis was performed using anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody from 6, 12, 24, and 30 h.p.i. (C).

Activation of p38 MAPK in SARS-CoV-infected cells

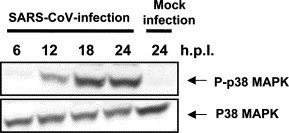

Fig. 1, Fig. 2 indicated that viral-specific proteins were synthesized at least 6 h.p.i., and the signaling pathway in response to stress should be activated from at least 6 to 24 h.p.i. by SARS-CoV-infection. Synthetic dsRNA poly(I)–poly(C) activates p38 MAPK and JNK/SAPK pathways in fibroblasts [15]: hence, double-stranded RNA intermediates of SARS-CoV that accumulate in infected cells may also trigger the p38 MAPK activation pathway. It was reported that p38 MAPK was activated in MHV-infected cells, and MHV replication has been shown to be necessary for p38 MAPK activation [7]. Therefore, the kinetics of p38 MAPK activation in SARS-CoV-infected Vero E6 cells were analyzed. Vero E6 cells were infected with SARS-CoV at an m.o.i. of 5, and cell extracts were prepared at various times p.i. Western blotting analysis indicated an increase in the amount of phosphorylated p38 MAPK in the cells (Fig. 3 ). The p38 MAPK phosphorylation was not transient and reached the maximal level at 18 h.p.i. The role of p38 MAPK signaling pathway in cellular responses is diverse, depending on the cell type and stimulation. Thus, the p38 MAPK signaling pathway promotes both cell death and survival [16], [17], [18]. Therefore, investigation of the p38 MAPK-downstream targets is important to understand the mechanisms of cell death induced by SARS-CoV-infection.

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in SARS-CoV-infected Vero E6 cells. Phosphorylated and unphosphorylated p38 MAPK were detected by Western blotting analysis using proteins isolated from SARS-CoV-infected Vero E6 cells at 6, 12, 18, and 24 h.p.i.

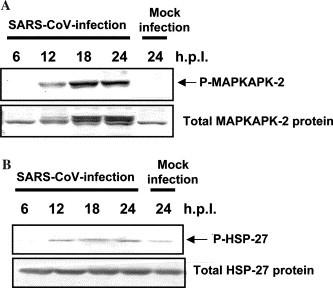

MAPKAPK-2 and HSP-27 phosphorylation by SARS-CoV-infection

One of the downstream effectors of p38 MAPK is MAPK-activated protein kinase (MAPKAPK)-2, which is activated in response to stress and growth factors [19], [20]. We examined whether SARS-CoV-infection results in activation of this MAPKAPK-2 in Vero E6 cells. As shown in Fig. 4A , MAPKAPK-2 was phosphorylated in SARS-CoV-infected Vero E6 cells. To determine whether the substrates of MAPKAPK-2 are phosphorylated in the virus-infected cells, Western blotting analysis was performed using anti-phospho heat shock protein (HSP)-27. As shown in Fig. 4B, Hsp-27 was phosphorylated in SARS-CoV-infected cells at 12 h.p.i. A previous study showed that Hsp-27 has anti-apoptotic activity by inhibiting apoptosome formation [21].

Fig. 4.

Phosphorylation of MAPKAPK-2 and HSP-27 in virus-infected cells. (A) Phosphorylated and unphosphorylated MAPKAPK-2 were detected by Western blotting analysis. (B) Phosphorylated and unphosphorylated HSP-27 were detected by Western blotting analysis.

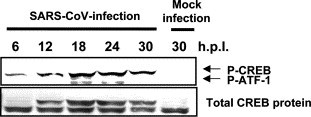

Phosphorylation of transcription factors CREB and ATF-1

We next examined whether cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), which is a substrate of mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase (MSK)-1, was phosphorylated in infected cells. MSK-1 is thought to be a substrate of p38 MAPK and/or extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK)1/2. CREB was identified as an activator that responds to the cAMP-dependent signaling pathway and is also known to mediate an important survival signal under various conditions [22], [23], [24]. For example, the anti-apoptotic genes Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL are activated transcriptionally by phosphorylation of CREB in response to insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I stimulation in PC-12 cells [25], [26]. Immunoblot analysis (Fig. 5 ) indicated that the level of phosphorylated CREB was increased by SARS-CoV-infection. The anti-phospho CREB antibody used in this study also recognizes activation transcription factor (ATF)-1, which is a transcription factor. ATF-1 is a member of the CREB/ATF family that is phosphorylated by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) [27]. ATF-1 and CREB act as survival factors [28]. This result suggested that phosphorylation of CREB and ATF-1 induces an anti-apoptotic environment in SARS-CoV-infected cells.

Fig. 5.

Phosphorylation of CREB and ATF-1 in virus-infected cells. Phosphorylated and unphosphorylated CREB were detected by Western blotting analysis. Phosphorylated ATF-1 was also detected using anti-phospho CREB antibody.

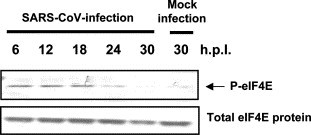

Phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF4E

The translation initiation factor, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), is phosphorylated by p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 [29], [30], and eIF4E enhances translation rates of cap-containing mRNAs [31]. In the case of mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), eIF4E phosphorylation is utilized to promote virus-specific protein synthesis. Western blotting analysis was performed using anti-phospho eIF4E antibody. As shown in Fig. 6 , the level of phosphorylated eIF4E was increased by SARS-CoV-infection.

Fig. 6.

Phosphorylation of eIF4E in virus-infected cells. Phosphorylated and unphosphorylated eIF4E were detected by Western blotting analysis.

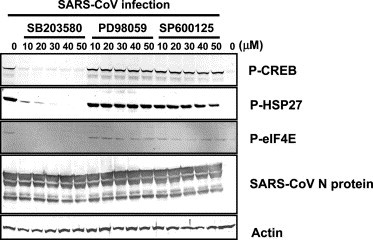

Specific effective doses of p38 MAPK inhibitor

To confirm that the phosphorylation of downstream targets of p38 MAPK was specifically mediated by p38 MAPK, SB203580 (p38 MAPK-specific inhibitor), PD98059 (ERK1/2-specific inhibitor), and SP600125 (JNK-specific inhibitor) were used for inhibition of those function. Fifty percent confluency of Vero E6 cells were treated with 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 μM inhibitors in DMSO for 24, 48, and 72 h, and then cell viability was assayed using WST-1 system (Roche Diagnostics). Treating cells with up to 50 μM all inhibitors had little effect on cell viability (data not shown). Next, we examined the determination of specific inhibitory doses of p38 MAPK inhibitor in SARS-CoV-infected Vero E6 cells. SARS-CoV were infected to Vero E6 cells for 1 h, and then, three kinds of inhibitors were added to the cells. Proteins were harvested at 18 h.p.i. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-phospho CREB, HSP-27, and eIF4E antibodies (Fig. 7 ). The result shows that the eIF4E was effectively inhibited to be of phosphorylated type by p38 inhibitor between 10 and 50 μM. The effective dose for inhibition of CREB phosphorylation was more than 20 μM, and phosphorylated HSP-27 was not detected at 40 and 50 μM. Thus, this result indicated that CREB, HSP-27, and eIF4E were specifically phosphorylated by p38 MAPK, because both the ERK1/2 and JNK inhibitors did not inhibit those of phosphorylation between 10 and 50 μM. The 20 μM SB203580 was used in the study of MHV [7] and this concentration is known to efficiently block p38 MAPK activity in vivo [32]. Therefore, we used 20 and 30 μM SB 203580 in subsequent experiments.

Fig. 7.

Effective doses of p38 MAPK inhibitor. SARS-CoV-infected Vero E6 cells were treated with SB203580 (p38 MAPK-specific inhibitor), PD98059 (ERK1/2-specific inhibitor), and SP600125 (JNK-specific inhibitor) for 18 h. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-phosphorylated HSP-27, CREB eIF4E antibodies. SARS-CoV N protein was also detected.

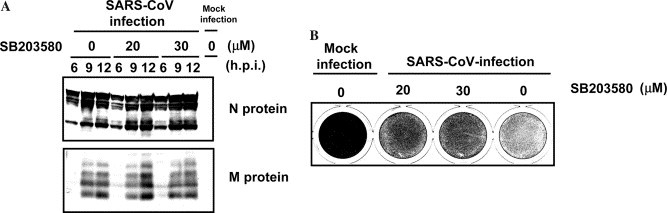

No requirement for p38 MAPK phosphorylation of SARS-CoV replication

The p38 MAPK-dependent increase in eIF4E phosphorylation to promote virus-specific protein synthesis and subsequent progeny virus production were found in MHV [7]. Activated p38 MAPK and the downstream target, eIF4E, increased translation of MHV-specific proteins. We also found that eIF4E was activated in SARS-CoV-infection at 18 h.p.i. (Fig. 7). At that time of p.i., there was no significant difference in the amount of N protein of SARS-CoV among three inhibitor-treated cells and untreated cells. Kinetic study of N protein synthesis (Fig. 1A) showed that N protein seems to be the maximum amount in viral infected cells between 12 and 18 h.p.i. To investigate whether enhancement of virus-specific protein synthesis through virus-induced eIF4E activation occurs in SARS-CoV-infected cells, we tested the effect of p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580, on SARS-CoV-specific protein synthesis at early time p.i. Ten m.o.i. of SARS-CoV was inoculated in Vero E6 cells for 1 h, and then, the cells were washed two times. These cells were treated with 20 and 30 μM SB203580 for 6, 9, and 12 h.p.i. Western blot analysis showed that kinetics of SARS-CoV-specific protein accumulation in infected Vero E6 cells in the presence and absence of SB 203580 were similar (Fig. 8A ). The phosphorylated eIF4E was detected at least 6 h.p.i. (Fig. 7) in SARS-CoV-infected cells. Taken together, SARS-CoV does not utilize activated eIF4E for its viral protein synthesis in Vero E6 cells. In addition, the CPEs caused by SARS-CoV-infection were slightly inhibited by SB203580 at late time p.i. (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Kinetics of N and M proteins synthesis in the presence of SB203580. After viral adsorption for 1 h, 20 and 30 μM of SB203580 was added to the cells. (A) Western blot analysis was performed at 6, 9, and 12 h.p.i. for detection of SARS-CoV N and M proteins. (B) Vero E6 cells were stained with 0.05% crystal violet at 41 h.p.i.

In this study, we determined the cellular mechanisms by which SARS-CoV causes the activation of physiological intracellular signaling cascades that lead to the phosphorylation and activation of downstream molecules. We showed that SARS-CoV-infection of permissive cells induced the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. As p38 MAPK is able to promote both cell death and survival [33], the substrates examined in this study and the other substrates of p38 MAPK may also induce cell death. Further studies are needed to determine which target molecules of p38 MAPK have inductive and preventative effects on apoptosis. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of activation of signaling transduction due to SARS-CoV-infection.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. F. Taguchi (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan) for useful suggestions. We also thank Ms. M. Ogata (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan) for her assistance. This work is partly supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and Japan Health Science Foundation, Tokyo, Japan.

References

- 1.Rota P.A, Oberste M.S, Monroe S.S, Nix W.A, Campagnoli R, Icenogle J.P, Penaranda S, Bankamp B, Maher K, Chen M.H, Tong S, Tamin A, Lowe L, Frace M, DeRisi J.L, Chen Q, Wang D, Erdman D.D, Peret T.C, Burns C, Ksiazek T.G, Rollin P.E, Sanchez A, Liffick S, Holloway B, Limor J, McCaustland K, Olsen-Rasmussen M, Fouchier R, Gunther S, Osterhaus A.D, Drosten C, Pallansch M.A, Anderson L.J, Bellini W.J. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300(5624):1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marra M.A, Jones S.J, Astell C.R, Holt R.A, Brooks-Wilson A, Butterfield Y.S, Khattra J, Asano J.K, Barber S.A, Chan S.Y, Cloutier A, Coughlin S.M, Freeman D, Girn N, Griffith O.L, Leach S.R, Mayo M, McDonald H, Montgomery S.B, Pandoh P.K, Petrescu A.S, Robertson A.G, Schein J.E, Siddiqui A, Smailus D.E, Stott J.M, Yang G.S, Plummer F, Andonov A, Artsob H, Bastien N, Bernard K, Booth T.F, Bowness D, Czub M, Drebot M, Fernando L, Flick R, Garbutt M, Gray M, Grolla A, Jones S, Feldmann H, Meyers A, Kabani A, Li Y, Normand S, Stroher U, Tipples G.A, Tyler S, Vogrig R, Ward D, Watson B, Brunham R.C, Krajden M, Petric M, Skowronski D.M, Upton C, Roper R.L. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300(5624):1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrington T.P, Johnson G.L. Organization and regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 1999;11:211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitmarsh A.J, Davis R.J. A central control for cell growth. Nature. 2000;403:255–256. doi: 10.1038/35002220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410(6824):37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyriakis J.M, Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee S, Narayanan K, Mizutani T, Makino S. Murine coronavirus replication-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation promotes interleukin-6 production and virus replication in cultured cells. J. Virol. 2002;76:5937–5948. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.5937-5948.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He R, Leeson A, Andonov A, Li Y, Bastien N, Cao J, Osiowy C, Dobie F, Cutts T, Ballantine M, Li X. Activation of AP-1 signal transduction pathway by SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;311:870–876. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drosten C, Gunther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt H.R, Becker S, Rabenau H, Panning M, Kolesnikova L, Fouchier R.A, Berger A, Burguiere A.M, Cinatl J, Eickmann M, Escriou N, Grywna K, Kramme S, Manuguerra J.C, Muller S, Rickerts V, Sturmer M, Vieth S, Klenk H.D, Osterhaus A.D, Schmitz H, Doerr W. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(20):1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thiel V, Ivanov K.A, Putics A, Hertzig T, Schelle B, Bayer S, Weissbrich B, Snijder E.J, Rabenau H, Doerr H.W, Gorbalenya A.E, Ziebuhr J. Mechanisms and enzymes involved in SARS coronavirus genome expression. J. Gen. Virol. 2003;84:2305–2315. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizutani T, Kobayashi M, Eshita Y, Shirato K, Kimura T, Ako Y, Miyoshi H, Takasaki T, Kurane T, Kariwa H, Umemura T, Takashima I. Involvement of the JNK-like protein of the Aedes albopictus mosquito cell line, C6/36, in phagocytosis, endocytosis and infection of West Nile virus. Insect Mol. Biol. 2003;12:491–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ksiazek T.G, Erdman D, Goldsmith C.S, Zaki S.R, Peret T, Emery S, Tong S, Urbani C, Comer J.A, Lim W, Rollin P.E, Dowell S.F, Ling A.E, Humphrey C.D, Shieh W.J, Guarner J, Paddock C.D, Rota P, Fields B, DeRisi J, Yang J.Y, Cox N, Hughes J.M, LeDuc J.W, Bellini W.J, Anderson L.J. SARS working group. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(20):1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C.J, Makino S. Murine coronavirus-induced apoptosis in 17Cl-1 cells involves a mitochondria-mediated pathway and its downstream caspase-8 activation and bid cleavage. Virology. 2002;302:321–332. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu C, Xu H.Y, Liu D.X. Induction of caspase-dependent apoptosis in cultured cells by the avian coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. J. Virol. 2001;75:6402–6409. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6402-6409.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iordanov M.S, Paranjape J.M, Zhou A, Wong J, Williams B.R, Meurs E.F, Silverman R.H, Magun B.E. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase by double-stranded RNA and encephalomyocarditis virus: involvement of RNase L, protein kinase R, and alternative pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:617–627. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.617-627.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juretic N, Santibanez J.F, Hurtado C, Martinez J. ERK 1,2 and p38 pathways are involved in the proliferative stimuli mediated by urokinase in osteoblastic SaOS-2 cell line. J. Cell. Biochem. 2001;83:92–98. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu B, Fang M, Lu Y, Mills G.B, Fan Z. Involvement of JNK-mediated pathway in EGF-mediated protection against paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in SiHa human cervical cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer. 2001;85:303–311. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yosimichi G, Nakanishi T, Nishida T, Hattori T, Takano-Yamamoto T, Takigawa M. CTGF/Hcs24 induces chondrocyte differentiation through a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38MAPK), and proliferation through a p44/42 MAPK/extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK) Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:6058–6065. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foltz I.N, Lee J.C, Young P.R, Schrader J.W. Hemopoietic growth factors with the exception of interleukin-4 activate the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:3296–3301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freshney N.W, Rawlinson L, Guesdon F, Jones E, Cowley S, Hsuan J, Saklatvala J. Interleukin-1 activates a novel protein kinase cascade that results in the phosphorylation of Hsp27. Cell. 1994;78:1039–1049. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrido C, Schmitt E, Cande C, Vahsen N, Parcellier A, Kroemer G. HSP27 and HSP70: potentially oncogenic apoptosis inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:579–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan Y, Rouse J, Zhang A, Cariati S, Cohen P, Comb M.J. FGF and stress regulate CREB and ATF-1 via a pathway involving p38 MAP kinase and MAPKAP kinase-2. EMBO J. 1996;15:4629–4642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ginty D.D, Bonni A, Greenberg M.E. Nerve growth factor activates a Ras-dependent protein kinase that stimulates c-fos transcription via phosphorylation of CREB. Cell. 1994;77:713–725. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Knethen A, Lotero A, Brune B. Etoposide and cisplatin induced apoptosis in activated RAW 264.7 macrophages is attenuated by cAMP-induced gene expression. Oncogene. 1998;17:387–394. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pugazhenthi S, Boras T, O’Connor D, Meintzer M.K, Heidenreich K.A, Reusch J.E. Insulin-like growth factor I-mediated activation of the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein in PC12 cells. Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:2829–2837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parrizas M, LeRoith D. Specific inhibition of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity and biological function by tyrphostins. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1355–1358. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.4.5092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee K.A, Masson N. Transcriptional regulation by CREB and its relatives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1174:221–233. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90191-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jean D, Harbison M, McConkey D.J, Ronai Z, Bar-Eli M. CREB and its associated proteins act as survival factors for human melanoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:24884–24890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morley S.J, McKendrick L. Involvement of stress-activated protein kinase and p38/RK mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways in the enhanced phosphorylation of initiation factor 4E in NIH 3T3 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:17887–17893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pyronnet S, Imataka H, Gingras A.C, Fukunaga R, Hunter T, Sonenberg N. Human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) recruits mnk1 to phosphorylate eIF4E. EMBO J. 1999;18:270–279. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gingras A.C, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuenda A, Alessi D.R. Use of kinase inhibitors to dissect signaling pathways. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;99:161–175. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-054-3:161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dent P, Yacoub A, Fisher P.B, Hagan P.M.P, Grant S. MAPK pathways in radiation responses. Oncogene. 2003;22:5885–5896. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]