Short abstract

Objective

We aimed to investigate the influence of depression and self-esteem on oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) in students.

Methods

Among the 67 included participants, we measured self-esteem using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, severity of depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), personality dimensions with the Neuroticism–Extraversion–Openness Five-Factor Inventory, and OHRQoL using the Oral Health Impact Profile 49 (OHIP-49).

Results

Among all participants, 7.5% (n = 5) had the dominant personality trait openness to experience, 11.9% (n = 8) presented a neurotic personality type, and 64.% (n = 11) had an extraverted personality type. The most frequent was conscientious personality type, accounting for 64.2% (n = 43) of participants. Our results showed a significant correlation between increased PHQ-9 scores and OHIP scores (Spearman’s r = 0.280); thus, participants with poorer oral health tended to have more severe depression. An increase in depression severity was significantly and positively correlated with increased scores across the other two OHIP subcategories, physical pain (Spearman’s r = 0.314) and physical disability (Spearman’s r = 0.290).

Conclusion

The presence and severity of depression influences OHRQoL. An important factor in the presence of depression and level of self-esteem is the personality type, especially the neuroticism dimension.

Keywords: Personality traits, psychosocial aspects, dentistry, oral health impact profile, depression, self-esteem, quality of life

Introduction

Previous studies have revealed that the association between objective measures of dental disease (such as the presence of dental caries or periodontal attachment loss) and patients’ opinions of oral status is weak and objective measures do not accurately reflect patients’ perceptions. The limitations of the “biomedical” paradigm of health have been recognized, especially because this model deals only with disease. The psychiatrist George L. Engel proposed a holistic alternative in formulating the biopsychosocial model, which states that only by combining biological, psychological, and social factors can the concept of health be better explained.1

The biological component of the biopsychosocial model is best described as the cause of illness. Different psychological factors such as lack of self-control, low self-esteem, emotional disturbance, and negative thinking as potential causes of health problems are explained by the psychological component of the biopsychosocial model. The social component of the biopsychosocial model investigates the impact of different social factors on health, such as socioeconomic status, poverty, culture, technology, and religion.2

Until recently, the psychosocial consequences of oral health conditions have received little attention, as these are rarely life threatening. Historically, the oral cavity has been dissociated from the rest of the body when considering general health status. Recent research has highlighted that oral disorders have emotional and psychosocial consequences that are as serious as other disorders. Studies have indicated that approximately 160 million work hours per year are lost owing to oral disorders.3

Many measures have been introduced to assess and describe oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). There is evidence that oral health influences the mental health of patients, changing their self-esteem, mood, and satisfaction with health services and even influencing their social life and life quality.4 However, self-esteem and disturbed mood can also be expected to influence oral health: for example, the presence of depression has been associated with smoking,5,6 drinking,6–8 and a lack of regular physical exercise,9,10 which influences how a person perceives their OHRQoL. Thus, there is a complex circular relationship between psychological factors (i.e., self-esteem, disturbed mood) and OHRQoL.

Because personality traits and self-esteem directly influence each other11 and personality traits are important to OHRQoL,12 we introduced this psychological dimension in this study. Self-esteem has been found to be correlated with each of the “Big Five” factors.11,12 Recent studies have demonstrated that psychological factors such as personality traits and self-esteem are significantly associated with quality of life rating. Moreover, there is evidence of an important relationship between some psychological profiles and satisfaction with dental status, dental treatment, and orthodontic needs. These findings suggest that some personality traits such as neuroticism, extroversion, and openness could act as independent predictors of a patient’s OHRQoL.11–13

Personality variables are also correlated with disposition and mood, and some personality disorders predispose affected individuals to the development of affective disorders. In this study, we analyzed the influence of self-esteem and the presence/severity of depression on OHROQoL, by first defining groups according to Big Five personality structures.13,14 The five-factor model (Big Five) is the most widely researched structural model of personality and was developed using a lexical approach.13

A reliable way to quantify OHRQoL is with use of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP), which estimates a person’s perception about the impact of oral disorders on well-being.15 The aim of the present study was to investigate the influence of depression and self-esteem on OHRQoL as measured with the OHIP.

Methods

Study design and patients

The study design and consent forms were approved by the Ethics Committee of the “Pius Branzeu” Emergency County Hospital, Timisoara (no. 154/15.02.2019). All participants were informed about the research aims, and informed consent was obtained before the beginning of the study. This research was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for research regarding the safety of human subjects.

The participants included in the study were students attending medical school at a university in Timisoara, Romania. The inclusion criterion was students who were willing to participate in the study. We excluded participants who did not complete all questions on the questionnaire. The included participants completed a three-part questionnaire comprising the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Neuroticism–Extraversion–Openness Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), and the Romanian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile-49 (OHIP-49).

The impact of oral discomfort on OHRQoL was measured using the Romanian version of the OHIP-49.16 This questionnaire is based on the conceptual dimensions of OHRQoL and is used to assess patients’ experience related to functional limitation, physical discomfort, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap. The 49 questions of the OHIP include a subset of 9 questions addressing functional limitation, 14 questions addressing physical pain, 20 questions on physical disability, and 6 questions addressing handicap. Each question is scored using a five-point Likert-type scale as follows: very often (4), fairly often (3), occasionally (2), hardly ever (1), and never (0). The final score for each domain is computed by summing all the answers.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale is a self-report questionnaire scored using a 10-item Likert scale. Every item is rated on a four-point scale, from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Scores range from 0 to 30, with scores between 15 and 25 considered within normal range; scores below 15 suggest low self-esteem. The higher the score, the higher the self-esteem.17,18

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a self-report questionnaire used to evaluate the presence and severity of depression. The nine items of the scale are based on the nine diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Each item is rated on a four-point scale from “Not at all” (0) to “Nearly every day” (3). A higher PHQ-9 score is associated with more severe depression. Based on this score, the severity of depression may be divided into three groups: minimal or mild (PHQ-9 score <10), moderate (PHQ-9 score 10–19), and severe (PHQ-9 score >19).19

The Romanian version of the NEO-FFI20 is a shortened version of the revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI) developed by McCrae and Costa in 1989.21 The scale assesses openness to experience, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability (neuroticism), the five major dimensions of personality. The self-report questionnaire consists in 60 items, 12 items for each personality dimension. Every item is rated by respondents on a five-point Likert-type scale from “strong disagreement” (1) to “strong agreement” (5). Personality dimension scores are calculated by summing the item scores that correspond to the related subscale. The highest score on the subscale corresponding to one of the five dimensions indicates the dominant personality trait.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to both collect and analyze the data in the present study. Results for categorical variables are presented as number of individuals and percentage of the sub-group total; variables with nonparametric distribution are presented as median [interquartile range], minimum and maximum, whereas numerical values with Gaussian distribution are presented as average value ± standard deviation. To assess the relationship between OHIP scores and character type, the cohort was divided according to the dominant personality trait: extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness to experience, or neuroticism. Consequently, an analysis was conducted of these groups to assess the differences in OHIP scores.

The unpaired Student t-test (for two groups) and analysis of variance test (for more than two groups) were used to compare differences in the average values. Assessment regarding significance of the variance recorded for median values was done using the Mann–Whitney U test (for two medians) and Kruskal–Wallis test (for more than two medians). The strength of the association between two numerical values was assessed by calculating the Spearman’s rho value. A stronger correlation between variables is indicated with a value close to −1 or 1 whereas a value closer to 0 indicates a weak correlation.

The Kolmogorov–Smirnoff test was used to evaluate the significance of differences between the hypothetical Gaussian distribution and that of the observed variables. A nonparametric distribution was indicated with a p-value <0.05 in this test. Levene’s test was used for heteroscedasticity testing of the variable’s distribution in two groups. A p-value <0.05 obtained in Levene’s test led to an assumption of heteroscedastic variance between groups. In this study, a p-value lower <0.05 was regarded as the threshold for statistical significance

Results

Participant characteristics

Initially, 87 participants took part in the study; however, after excluding those with incomplete questionnaire responses, only 67 participants were enrolled in the present study. Participants’ median age was 25 years, and 41.8% were male (n = 28). Of the total, 7.5% (n = 5) were in the group whose dominant personality trait was openness to experience, 11.9% (n = 8) were in the neurotic personality group, and 16.4% (n = 11) had an extraverted personality type. The most frequently encountered personality type was conscientious, accounting for 64.2% (n = 43) of participants. The characteristics of the included students are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Studied parameter | Result |

|---|---|

| Male sexa | 28 (41.8%) |

| Female sexa | 39 (58.2%) |

| Age (years)b | 24 |

| Personality traita | |

| Neuroticism | 8 (11.9%) |

| Extraversion | 11 (16.4%) |

| Openness to experience | 5 (7.5%) |

| Conscientiousness | 43 (64.2%) |

aResults for categorical variables are presented as frequency (percentage) of the total.

bResults for numerical variables with nonparametric distribution are presented as median [interquartile range].

PHQ-9 score distribution

In the study group, PHQ-9 scores showed a distribution skewed to the right (skewness 0.765 ± 0.293), with the most values in the lower score range (0–8 points). The distribution of PHQ-9 scores is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score distribution.

Based on these values, we concluded that no study participants had manifestations of severe depression and most had symptomatology of mild depression (49.3%), with PHQ-9 scores between 5 and 9 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of depression severity in the study group.

| Depression severity | Number | Percentage [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|

| None–minimal | 24 | 35.8% [25.4 to 47.8] |

| Mild | 33 | 49.3% [37.7 to 60.9] |

| Moderate | 8 | 11.9% [6.2 to 21.8] |

| Moderately severe | 2 | 3.0% [0.8 to 10.3] |

| Severe | 0 | 0% [0 to 5.4] |

CI, confidence interval.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale scores

Rosenberg scale scores recorded in our study sample had a normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk p = 0.194). Values of the Rosenberg score were slightly negative skewed; more individuals had higher self-esteem than significantly decreased self-esteem (Rosenberg skewness −0.308; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale score distribution.

According to the classification of self-esteem based on the Rosenberg score, most students in our cohort had normal self-esteem (65.7%) in contrast to those with low self-esteem (9.0%); 25.4% of participants reported higher values than expected. Students’ classification with respect to Rosenberg score is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Self-esteem scores in the study sample.

| Rosenberg scale score | Number | Percentage [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|

| Low self-esteem (<15) | 6 | 9.0% [4.2 to 18.2] |

| Normal self-esteem (15–25) | 44 | 65.7% [53.7 to 75.9] |

| High self-esteem (>25) | 17 | 25.4% [16.5 to 36.9] |

CI, confidence interval.

Relationships between oral health, depression, and self-esteem and character type

Our study results indicated that the character type exhibited by individuals impacted depression severity assessed using the PHQ-9 (p = 0.04, Kruskal–Wallis test for unequal variances). The highest score was achieved by those with a dominant personality trait of openness to experience, with a median score of 9; this was closely followed by those with a neurotic personality type, with a median score of 8. The lowest scores were among those with dominant traits of conscientiousness and extraversion, with median scores of 5 and 6, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores in relation to dominant personality trait.

Furthermore, the character type impacted participants’ self-esteem, as assessed using the Rosenberg scale (p = 0.033, Kruskal–Wallis test for unequal variances). Whereas scores for all character types were in the normal range, their actual values differed, with a median score of 17 in students with a dominant neurotic type to a median score of 23 in those with a dominant conscientious type (Figure 4). Details regarding the influence of character type on PHQ-9 depression score and Rosenberg self-esteem score are given in Table 4.

Figure 4.

Self-esteem in relation to dominant personality trait.

Table 4.

PHQ-9 and Rosenberg scores in relation to main personality type.

| Personality trait | PHQ-9 score | Rosenberg scale score |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | 17 [13 to 20] | 8 [5 to 13] |

| Extraversion | 22 [21 to 26] | 6 [5 to 7] |

| Experience | 21 [20 to 23] | 9 [5 to 11] |

| Conscientiousness | 23 [20 to 26] | 5 [1 to 6] |

| p-value | 0.04 | 0.033 |

Results for variables with nonparametric distribution are presented as median [interquartile range].

p-values calculated using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

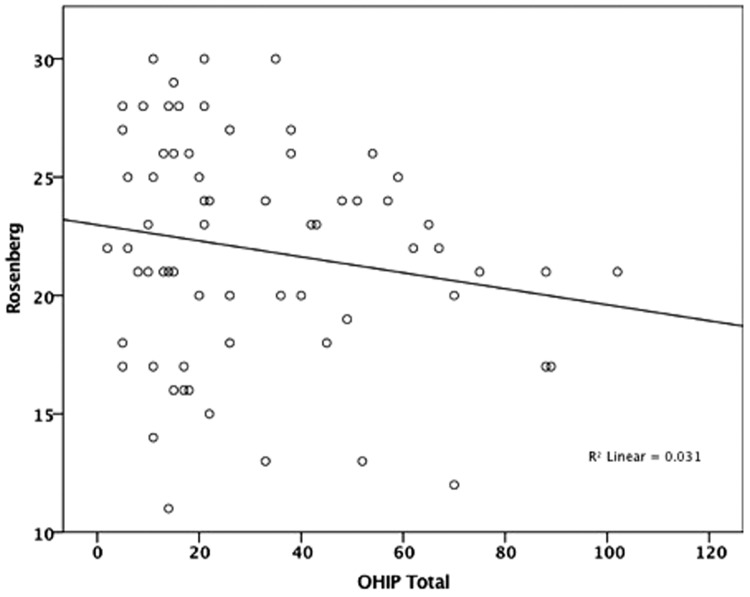

The present results showed a positive and significant correlation between increased PHQ-9 scores and OHIP total scores (Spearman’s r = 0.280, p<0.05), implying that individuals with poorer oral health tended to have more severe depression symptomatology (Figure 5). In contrast, there was no statistically significant correlation between Rosenberg scores and OHIP total outcomes (Spearman’s r = −0.153), indicating that oral health had no significant impact on participants’ self-esteem (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Correlations between the Oral Health Impact Profile and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores.

Figure 6.

Correlations between the Oral Health Impact Profile and Rosenberg scores.

Although results of the PHQ-9 did not correlate with OHIP functional limitation scores (Spearman’s r = 0.132) nor OHIP handicap scores, we found that an increase in depression severity was significantly and positively correlated with increased scores across the other two OHIP subcategories as follows: OHIP physical pain (Spearman’s r = 0.314, p = 0.01) and OHIP physical disability (Spearman’s r = 0.290, p = 0.017).

Discussion

The results of the present study indicated a positive and significant correlation between increased PHQ-9 scores and increased OHIP total scores as well as the OHIP subcategories of physical pain and physical disability.

Within the selected group, the level of self-esteem and severity of depression varied significantly according to the dominant personality trait. In terms of self-esteem, participants with neuroticism as their dominant personality trait had significantly lower self-esteem than those in the other three subgroups.

Defined as a personal perception of an individual’s worthiness in connection with a person’s social world, self-esteem is derived from the reflected appraisal of others and can have both positive and negative effects. Whereas an individual with low self-esteem feels helpless and inadequate, an individual with high self-esteem feels able to cope with adversity and sufficiently competent to achieve success.22

Self-esteem and personality are likely to share common developmental roots. Until now, most studies have reported correlations among the big five dimensions and self-esteem.11,23–26 In most studies, self-esteem has been found to correlate negatively with neuroticism and positively with extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness.26,27

The results of the present study are consistent with those of the studies mentioned above because the lowest self-esteem was found among neurotic participants. This can be reasonably expected as people with these characteristics have a tendency to experience negative and unpleasant emotions, vulnerability to stress, a lack of confidence, and they are easily frustrated and prone to guilt, moodiness, anger, insecurities in relationships, and have difficulty managing stress.

Good oral hygiene behaviors have been correlated with high self-esteem. Studies by Honkala et al. and Dumitrescu et al.28,29 showed that people with high self-esteem had good oral hygiene behaviors.

We observed that depression severity was lowest in participants who had a dominant personality trait of conscientiousness or extraversion; those with a dominant personality of openness to experience or neuroticism had higher levels of depression.

The results of this study are consistent with those of a meta-analysis of Kotov et al.,30 which showed that patients with depression scored higher than non-clinical patients for neuroticism and lower for extraversion and conscientiousness. Similarly, a later study by Jourdy and Petot found a high positive correlation between neuroticism and severity of depression, and a medium negative correlation with extraversion and conscientiousness.31 Thus, because neurotic individuals have lower self-esteem and higher levels of depression than conscientious and extraverted participants, the neurotic personality trait likely has a negative impact on oral hygiene.

Severe depression has been associated with poorer oral and dental health, characterized by increased levels of untreated tooth decay, gingivitis and periodontal disease, poor oral hygiene, soft tissue lesions and disease, tooth loss at an early age, and an increased risk of oral cancer owing to the use of tobacco and alcohol. A study by Hugo et al.32 showed that depressive symptoms may act as determinants of caries and might directly influence the evolution of untreated caries, proving to be a powerful predictor of the disease. Previous findings have showed that adults with depressive symptoms tend to more frequently rate their oral health as poor and have less favorable dental behaviors.33

Depression has also been correlated with modified behaviors related to maintaining proper oral hygiene.34 In our study, the intensity of depression showed a significant positive correlation with OHIP total scores and the OHIP subscales of physical pain and physical disability. The higher the severity of depression, the lower the quality of life in terms of oral health, as well as physical pain and physical disability. This is understandable especially owing to the impact of depression on oral health, as previously mentioned.

For these reasons, it is critical to promote changes in behaviors and habits to achieve good oral health in patients with depression. Considering the impact of depression on the cognitive and volitional level of the patient, as mentioned by Friedlander,35 dentists should be supportive and have patience with depressed individuals, sending clear and well-structured messages about oral health hygiene and undergoing regular dental check-ups. Our results can be explained by the participants being medical students who were likely better educated with respect to maintaining good oral hygiene. In addition, interpretation of the OHIP scale is not expected to be the same in our study population as in the general adult population. Dental problems among older adults are more complex than those among younger people; thus, our findings cannot be extrapolated to individuals that do not have complete dentition.

Interestingly, we did not find any significant correlation between the level of self-esteem as assessed using the Rosenberg scale and OHRQoL as assessed with total OHIP scores. This is interesting within the context that self-esteem is considered an important psychological factor in the biopsychological model formulated by psychiatrist George L. Engel. In addition, the studies mentioned above reported a beneficial impact of increased self-esteem on the perception of oral health. The influence of self-esteem was found to be significant in a study by Ozhayat, in which low self-esteem and high negative affectivity were associated with worse OHRQoL in patients with partial tooth loss.36 Further, in a group of children receiving orthodontic treatment, Agou et al.37 postulated the mediator role of self-esteem when evaluating OHRQoL.

Limitations

The small population size is a limitation of this study. In addition, the enrolled participants were selected from among university students; therefore, the results cannot be generalized to the entire population.

Conclusion

The presence and severity of depression influences OHRQoL, as opposed to self-esteem. An important factor in the presence of depression and level of self-esteem of patients is the dominant personality trait, especially the neurotic dimension. Thus, in anticipating the subsequent evolution of oral health in a patient, it is important to also analyze psychological factors, at least in terms of the existence of depression and the personality traits lying behind it.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD

Bogdan Timar https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0993-6206

References

- 1.Engel G. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry 1980; 137: 535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandran T, Ravindranath NS, Raju Ret al. Psychological determinants of oral health– a review. Int J Oral Health Med Res 2016; 3: 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomson WM, Caspi A, Poulton Ret al. Personality and oral health. Eur J Oral Sci 2011; 119: 366–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkan A, Cakmak O, Yilmaz Set al. Relationship between psychological factors and oral health status and behaviours. Oral Health Prev Dent 2015; 13: 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall SM, Munoz RF, Reus VIet al. Nicotine, negative affect, and depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1993; 61: 761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green CA, Pope CR. Depressive symptoms, health promotion, and health risk behaviors. Am J Health Promot 2000; 15: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simantov E, Schoen C, Klein JD. Health-compromising behaviors: Why do adolescents smoke or drink? Identifying underlying risk and protective factors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000; 154: 1025–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poikolainen K, Lindeman S, Aro H. Cigarette smoking, alcohol intoxication and major depressive episode in a representative population sample. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001; 55: 573–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allgover A, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Depressive symptoms, social support, and personal health behaviors in young men and women. Health Psychol 2001; 20: 223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kivela SL, Pahkala K. Relationships between health behaviour and depression in the aged. Aging 1991; 3: 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robins RW, Tracy JL, Trzesniewski Ket al. Personality correlates of self-esteem. J Res Pers 2001; 35: 463–482. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagaland T, Kadanakuppe S, Raju R. Is there an association of self-esteem and negative affectivity with oral health related quality of life in patients with tooth loss?: a hospital based study. Int J Oral Health Med Res 2016; 3: 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg LR, Rosolack TK. The Big Five factor structure as an integrative framework: An empirical comparison with Eysenck’s P-E-N model In: Halverson CF. Jr, Kohnstamm GA, Martin RP. (eds) The developing structure of temperament and personality from infancy to adulthood. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, 1994, pp.7–35. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr. The five-factor theory of personality In: John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA. (eds) Handbook of personality: theory and research. 3rd ed New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2008, pp.159–181. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dental Health 1994; 11: 3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grecu AG, Dudea D, Balazsi Ret al. Romanian version of the oral health impact profile-49 questionnaire: validation and preliminary assessment of the psychometrical properties. Clujul Medical 2015; 88: 530–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crandal R. The measurement of self-esteem and related constructs In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR. (eds) Measures of social psychological attitudes. Revised edition Ann Arbor: ISR, 1973, pp.80–82. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Patient Health Questionnaire Study Group. Validity and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA 1999; 282: 1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. NEO PI-R. Manual tehnic: Inventarul de Personalitate NEO, Revizuit (NEO PI-R) & Inventarul NEO-FFI, Revizuit (NEO-FFI), Ed. Cluj Napoca: Sinapsis, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCrae RR, Costa PT. The structure of interpersonal traits: Wiggins’s circumplex and the five-factor model. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989; 56: 586–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macgregor DM, Balding JW. Self-esteem as a predictor of toothbrushing behaviour in young adolescents. J Clin Periodontol 1991; 18: 312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller T. Images of the familiar: individual differences and implicit leadership theories. Leadership Quarterly 1999; 10: 589–607. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pullmann H, Allik J. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: its dimensionality, stability and personality correlates in Estonian. Pers Indiv Differ 2000; 28: 701–715. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robins RW, Hendin HM, Trzesniewski KH. Measuring global self-esteem: construct validation of a single item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2001; 27: 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amirazodi F, Amirazodi M. Personality traits and self-esteem. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2011; 29: 713–716. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson D, Suls J, Haig J. Global self-esteem in relation to structural models of personality and affectivity. J Pers Soc Psychology 2002; 83: 185–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honkala S, Honkala E, Al-Sahli N. Do life or school satisfaction and self-esteem indicators explain the oral hygiene habits of schoolchildren? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2007; 35: 337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dumitrescu AL, Zetu L, Teslaru S. Instability of self-esteem, self-confidence, self-liking, self-control, self-competence and perfectionism: associations with oral health status and oral health-related behaviours. J Contemp Dent Pract 2012; 12: 136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt Fet al. Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2010; 136: 768–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jourdy J, Petot JM. Relationships between personality traits and depression in the light of the “Big Five” and their different facets. L’Évolution Psychiatrique 2017; 82: e27–e37. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hugo FN, Hilgert JB, de Sousa LRet al. Depressive symptoms and untreated dental caries in older independently living South Brazilians. Caries Res 2012; 46: 376–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anttila S, Knuuttila M, Ylostalo Pet al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in relation to dental health behavior and self-perceived dental treatment need. Eur J Oral Sci 2006; 114: 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park SJ, Ko KD, Shin SIet al. Association of oral health behaviors and status with depression: results from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2010. J Public Health Dent 2014; 74: 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedlander AH, Norman DC. Late-life depression: psychopathology, medical interventions, and dental implications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002; 94: 404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozhayat EB. Influence of self-esteem and negative affectivity on oral health related quality of life in patients with partial tooth loss. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2013; 41: 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agou S, Locker D, Streiner DLet al. Impact of self-esteem on the oral-health-related quality of life of children with malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008; 134: 484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.