Abstract

A 2-day-old goat died suddenly after the onset of severe diarrhea. No specific gross lesions were observed except for a remarkably thin intestinal wall and watery intestinal contents. Histopathological analysis revealed large numbers of Gram-positive bacilli layered upon the intestinal epithelia of the small intestine. Heavy growth of only Clostridium perfringens type E, and no detection of the other enteric pathogens in the small intestine, suggests that C. perfringens type E contributed to the death of this kid. To our knowledge, this is the first isolation of C. perfringens type E from a goat with diarrhea.

Keywords: Clostridium perfringens type E, Diarrhea, Goat

1. Introduction

Clostridium perfringens is an important enteric pathogen in domestic animals. It is classified into 5 toxinotypes, designated A, B, C, D, and E, depending upon the ability of the bacteria to express four major toxins, namely alpha, beta, epsilon, and iota [1], [2], [3]. Each C. perfringens type is associated with certain human or animal diseases.

C. perfringens type E infection has rarely been reported in domestic animals with the exception of a few reports of rabbits with enterotoxemia, lambs with dysentery and neonatal calves with hemorrhagic enteritis and sudden death [2], [3], [4], [5]. C. perfringens type E strains are distinguished from other toxinotypes by their simultaneous production of alpha and iota toxin. C. perfringens iota toxin is a binary toxin consisting of two independent polypeptide chains: an enzymatic component (Ia) ADP-ribosylates skeletal muscle and nonmuscle actin and leads to cell rounding and death, and a binding component (Ib), which binds to the cell surface and translocates Ia into the cytosol [6]. Iota toxin has known biological consequences, such as lethality, dermonecrosis, and cytotoxicity, but C. perfringens type E infection has been generally considered a disease with rare occurrences in domestic animals [1], [2], [3], [4], [6]. There has been no prior report of this type of infection in goats. Here, we report the first isolation of C. perfringens type E from a neonatal goat with a history of diarrhea and sudden death.

2. Case report

In August 2010, a goat farm experienced sudden death of neonatal kids affected with severe diarrhea. Among the diseased kids, a 2-day-old kid was referred to the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency where necropsy was performed on the following day the kid died. Tissue samples of cerebrum, cerebellum, brain stem, heart, lung, liver, spleen, kidney, stomach, and small and large intestines were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histopathology. The fixed tissues were processed routinely and 4 μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Intestinal sections were also Gram stained. The intestinal contents were aseptically collected and then inoculated onto sheep blood agar (Asan Pharmaceutical, Republic of Korea) and MacConkey agar (Difco, U.S.A.). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Five anaerobic isolates demonstrating characteristic dual hemolytic zones were identified as C. perfringens by use of a microbial identification system (VITEK® 2 compact, BioMérieux, France). To distinguish toxinotype, multiplex PCR targeting the four major toxin genes was performed [7]. Also, the enterotoxin gene was investigated with PCR as described previously [8]. To detect enterotoxin production by the isolate, we used a reversed passive latex agglutination kit (PET-RPLA, DENKA SEIKEN CO., LTD., Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To determine the possibility of parasitic infection, a standard flotation method was carried out to detect parasite eggs. Additional PCR was performed to detect major caprine viral enteric pathogens, including rotavirus, coronavirus, border disease virus (BDV), and bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) [9], [10], [11].

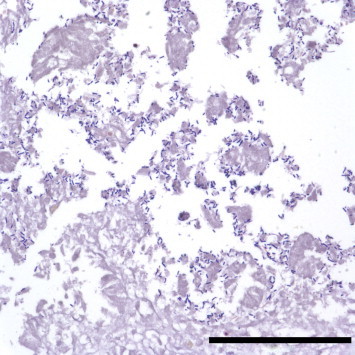

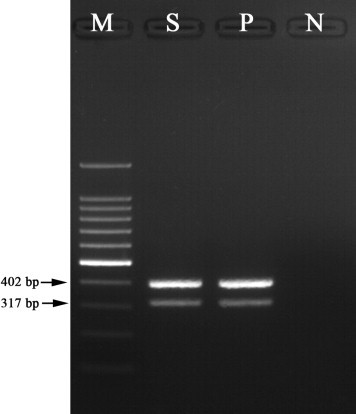

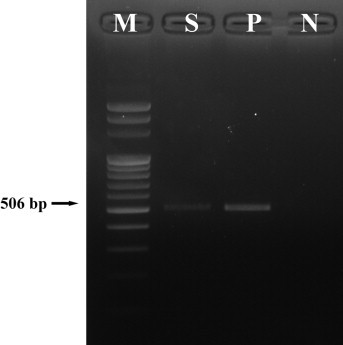

Grossly, the small intestine (jejunum and ileum) was distended with gas and watery yellowish intestinal contents. There were no specific lesions of the major organs except for a remarkably thin intestinal wall. Histopathologically, the intestinal epithelium was exfoliated and the lumen of the small intestine was filled with multifocal necrotic cell debris. A large number of Gram-positive bacilli were attached to the mucosal layer of the small intestine (Fig. 1 ). There was no histological change other than small intestine. Heavy growth of C. perfringens was observed in anaerobic culture of intestinal contents. All isolates were determined by PCR to be toxinotype E (Fig. 2 ). The gene for enterotoxin was also detected (Fig. 3 ), but production of enterotoxin was not detected by PET-RPLA. No other aerobic or anaerobic pathogens were detected. No parasitic eggs were found in the intestinal contents. PCR results were also negative for rotavirus, coronavirus, BDV, and BVDV.

Fig. 1.

Small intestine of the goat kid. Gram-positive bacilli are observed in the mucosal layer. Gram stain. Bar = 100 μm.

Fig. 2.

Result of Clostridium perfringens PCR analysis using isolate from the small intestine. The product sizes are 402 bp for alpha toxin and 317 bp for iota toxin; lane M, 100 bp marker; lane S, DNA from the isolate; lane P, Clostridium perfringens type E as a positive control; lane N, distilled water as a negative control.

Fig. 3.

PCR result of Clostridium perfringens isolate from the small intestine. The product size is 506 bp for enterotoxin; lane M, 100 bp marker; lane S, DNA from the isolate; lane P, enterotoxin producing Clostridium perfringens type A as a positive control; lane N, distilled water as a negative control.

3. Discussion

C. perfringens type E infection has rarely been reported in domestic animals [2], [3], [4]. In goats, enterotoxemia by C. perfringens type D has been well described, with resultant hemorrhagic diarrhea and fibrinous hemorrhagic colitis [2], [3]. However, C. perfringens type E infection in goats has not been reported prior, and information on C. perfringens types A, B, and C infection in goats is also limited [2], [3]. From 2010 to 2011, we surveyed 249 fecal samples of goats to determine the prevalence of C. perfringens toxinotypes: 20 type A (8.0%), 14 type D (5.6%), and 1 type E (0.4%) were isolated (unpublished data). These data are in agreement with previous reports that C. perfringens type E infection is rare in goats [1], [2], [3], [4]. However, other reports demonstrated that C. perfringens type E strains are present at a rate of approximately 4%–10% in neonatal calves with hemorrhagic enteritis and sudden death [3], [4]. These authors hold that type E strains are not rare in neonatal calves with these clinical signs and suggest that more rigorous epidemiologic and diagnostic pursuit of similar cases is needed [4].

C. perfringens is a normal inhabitant of the intestines of animals and humans, but bacterial proliferation and toxin production are usually associated with sudden changes in diet or other factors, including accidental overdose of netobimin, cold weather stress, a concomitant infestation with coccidia, and heavy worm infection [2], [3]. In the present case, no antihelmintic drugs were administered and no parasitic eggs were observed by fecal testing. Cold weather stress should not have been a factor in the current case due to the time of the year. The source of infection in the present case was suspected to be its dam or an undetermined environmental exposure. C. perfringens may have proliferated and produced toxins in the intestine of the kid as the normal flora was not yet completely established.

The C. perfringens isolated in this case was confirmed to be type E by multiplex PCR. The genotyping of C. perfringens has become simplified for routine diagnosis by multiplex PCR detecting major toxins [7], [8]. This method enables testing of larger numbers of samples with greater accuracy than previous methods, such as mouse neutralization test or ELISA. Even though detection of iota toxin is still desirable for diagnosis, mouse test is time-consuming, expensive, lack of precision, and unavoidable use of live animals [12]. Commercial ELISA kits that detect alpha, beta, epsilon, and enterotoxin have been extensively used, but there are no commercial systems for detection of iota toxin [3].

Enterotoxin is the best understood virulence factor of C. perfringens and is responsible for the disintegration of tight junctions between endothelial cells in the gut of dogs, pigs, horses, and human beings [1], [2]. The enterotoxin gene was amplified from the type E isolate, but production of enterotoxin was not detected. This finding is consistent with previous C. perfringens type E cases where the isolates carried the enterotoxin gene but production of enterotoxin was not detected [4], [13]. This finding is not surprising as Billington and others suggested that highly conserved, silent enterotoxin gene sequences, located adjacent to the iota toxin genes on episomal DNA, are present in most type E isolates [13]. However, novel type E strains carrying a variant functional enterotoxin gene and iota toxin gene were identified recently. Thus, type E strains may be more common than previously appreciated [14].

The affected kid demonstrated severe diarrhea in the present study. Heavy growth of only C. perfringens was obtained from intestinal contents, and alpha and iota toxin genes were detected from the isolates, while other pathogens were absent. To the authors' knowledge, this is the first isolation of C. perfringens type E from a goat with diarrhea. This finding suggests that more consideration should be given to type E-associated disease when considering the health care of goat kids with neonatal diarrhea and sudden death, as there are no currently available commercial vaccines to protect against type E infection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants (B-AD21-2010-11-03) from National Veterinary Research and Development Foundation from the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Songer J.G. Clostridial enteric diseases of domestic animals. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:216–234. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uzal F.A. Diagnosis of Clostridium perfringens intestinal infections in sheep and goats. Anaerobe. 2004;10:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uzal F.A., Songer J.G. Diagnosis of Clostridium perfringens intestinal infections in sheep and goats. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008;20:253–265. doi: 10.1177/104063870802000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Songer J.G., Miskimmins D.W. Clostridium perfringens type E enteritis in calves: two cases and a brief review of the literature. Anaerobe. 2004;10:239–242. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baskerville M., Wood M., Seamer J.H. Clostridium perfringens type E enterotoxaemia in rabbits. Vet Rec. 1980;107:18–19. doi: 10.1136/vr.107.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakurai J., Nagahama M., Oda M., Tsuge H., Kobayashi K. Clostridium perfringens iota-toxin: structure and function. Toxins (Basel) 2009;1:208–228. doi: 10.3390/toxins1020208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoo H.S., Lee S.U., Park K.Y., Park Y.H. Molecular typing and epidemiological survey of prevalence of Clostridium perfringens types by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:228–232. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.228-232.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baums C.G., Schotte U., Amtsberg G., Goethe R. Diagnostic multiplex PCR for toxin genotyping of Clostridium perfringens isolates. Vet Microbiol. 2004;100:11–16. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(03)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vilcek S., Herring A.J., Herring J.A., Nettleton P.F., Lowings J.P., Paton D.J. Pestiviruses isolated from pigs, cattle and sheep can be allocated into at least three genogroups using polymerase chain reaction and restriction endonuclease analysis. Arch Virol. 1994;136:309–323. doi: 10.1007/BF01321060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong J.H., Kim G.Y., Yoon S.S., Park S.J., Kim Y.J., Sung C.M. Molecular analysis of S gene of spike glycoprotein of winter dysentery bovine coronavirus circulated in Korea during 2002-2003. Virus Res. 2005;108:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda M., Kuga K., Miyazaki A., Suzuki T., Tasei K., Aita T. Development and application of one-step multiplex reverse transcription PCR for simultaneous detection of five diarrheal viruses in adult cattle. Arch Virol. 2012;157:1063–1069. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1271-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uzal F.A., Plumb J.J., Blackall L.L., Kelly W.R. PCR detection of Clostridium perfringens producing different toxins in faeces of goats. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;25:339–344. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billington S.J., Wieckowski E.U., Sarker M.R., Bueschel D., Songer J.G., McClane B.A. Clostridium perfringens type E animal enteritis isolates with highly conserved, silent enterotoxin gene sequences. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4531–4536. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4531-4536.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14.Miyamoto K., Yumine N., Mimura K., Nagahama M., Li J., McClane B.A. Identification of novel Clostridium perfringens type E strains that carry an iota toxin plasmid with a functional enterotoxin gene. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]