Abstract

Infections by Clostridium perfringens type A are perhaps the most common causes of clostridial hemorrhagic enteritis in neonatal ruminants. Affected calves exhibit tympany, hemorrhagic abomasitis, and abomasal ulceration. Gram-positive bacilli are often found on affected mucosa and in submucosa. Aspects of etiology beyond the infecting organism are little understood, but probably include dietary issues, perhaps relating to overfeeding, feeding of barely thawed or contaminated colostrum, or conditions which effect decreased gut motility. Fatal hemorrhagic enteritis in a cloned gaur calf is illustrative of the syndrome. The calf developed pasty yellow and bloody diarrhea, and the abdomen became distended and painful. In spite of intensive therapy, the calf died ∼48 h after birth. At necropsy, the distended abomasum contained clotted milk and bloody fluid, and the abomasal and omasal walls were thickened and hemorrhagic. The proximal duodenum was hemorrhagic and emphysematous, and microscopic examination revealed Gram-positive rods in association with acute, necrotizing, hemorrhagic mucosal inflammation. Isolates of C. perfringens from this calf were PCR positive for cpb2, the gene encoding beta2 toxin. This finding is of unknown significance; only 14.3% (8/56) of isolates from other calves with the syndrome have been cpb2 positive, and only 50% of cpb2 positive bovine isolates express CPB2. The most prominent needs to further our understanding of this problem are consistent experimental reproduction of the disease, elucidation of virulence attributes, and development and application of prevention and control strategies.

Keywords: Abomasitis, Clostridium perfringens type A, Gaur

1. Introduction

Clostridial infections of the gastrointestinal tract of calves remain a common problem [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], in spite of the widespread availability of effective immunoprophylactic products [6]. Neonatal infection by Clostridium perfringens type C (Table 1 ) is widely recognized [7], and, like other infections by toxin types of C. perfringens, type C may colonize rapidly in the absence of established normal flora [6]. Robust, hearty calves, usually less than 10 days of age, develop hemorrhagic, necrotic enteritis and enterotoxemia, often with abdominal pain [8], [9] and nervous signs. Death may be peracute, or following a clinical course of several days.

Table 1.

Diseases caused by toxin types of C. perfringens

| Toxin type | Diseases | Major toxins |

|---|---|---|

| A | Myonecrosis, food poisoning, necrotic enteritis in fowl, enterotoxemia in cattle and lambs, necrotizing enterocolitis in piglets; possibly equine colitis, canine hemorrhagic gastroenteritis | Alpha |

| B | Dysentery in newborn lambs, chronic enteritis in older lambs (“pine”), hemorrhagic enteritis in neonatal calves and foals, hemorrhagic enterotoxemia in adult sheep | Alpha, beta, epsilon |

| C | Enteritis necroticans (pigbel) in humans, necrotic enteritis in fowl, hemorrhagic or necrotic enterotoxemia in neonatal pigs, lambs, calves, goats, foals, acute enterotoxemia (“struck”) in adult sheep | Alpha, beta |

| D | Enterotoxemia in lambs (“pulpy kidney”) and calves, enterocolitis in neonatal and adult goats, possibly enterotoxemia in adult cattle | Alpha, epsilon |

| E | Enterotoxemia likely in calves and lambs, enteritis in rabbits; host range and disease type unclear | Alpha, iota |

Beta toxin is the prime player in pathogenesis of type C infections. Damage to micro-villi, mitochondria, and terminal capillaries precedes adherence of the organism to the jejunal mucosa [10], [11], [12], [13]. Widespread and progressive mucosal necrosis follows, and large numbers of Gram-positive bacilli can be demonstrated across vast areas of the mucosa [14]. Death is due, ultimately, to beta toxemia [14], [15], [16]. The disease cannot be reproduced with toxin alone [16], [17], [18], but protection is primarily antitoxic.

C. septicum also causes enteric infections in ruminants [19], [20], most notably as braxy, in which the organism establishes in the abomasum and produces a fatal bacteremia [2], [5], [21]. The pathogenetic mechanism may involve ingestion of frozen feed [5], [20], which impairs mucosal function, allowing dissemination of the organism and production of bacteremia [22]. The organism produces numerous potentially or putatively toxic products, but foremost among these is alpha toxin [23], [24]; immunity is primarily antitoxic.

C. perfringens type A has been associated with lamb enterotoxemia [25], [26] and is widely recognized as the cause of fowl necrotic enteritis [23] and necrotizing enteritis in neonatal pigs [27], [28], [29]. Diagnostic studies now suggest that it is the most common bacterial finding in cases of clostridial enteritis in neonatal calves [30], [31], [32], [33]. Affected calves often exhibit tympany, hemorrhagic abomasitis, and abomasal ulceration. Gram-positive bacilli are often found on the mucosa and in the submucosa [1], [34], [35]. The occurrence of type A organisms as normal flora in virtually all warm-blooded animals has complicated its assignment as an etiologic agent of enteric disease [6]. However, the disease can be reproduced experimentally with cultures of type A ([35], our unpublished data).

2. Case report

A normal male Asian gaur calf resulted from in vitro fertilization and embryo implantation into a domestic crossbred heifer. It weighed 88 lb (40 kg) when delivered by Caesarean section, and was given 6 pints of colostrum over the first 12 h. After 36 h, the calf developed pasty-yellow diarrhea, which soon became bloody. The abdomen became distended and painful, and in spite of intravenous fluid therapy and administration of C. perfringens type C and D antitoxin (intravenous and subcutaneous), antibiotics (penicillin and ceftiofur), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, the calf died ∼48 h after birth.

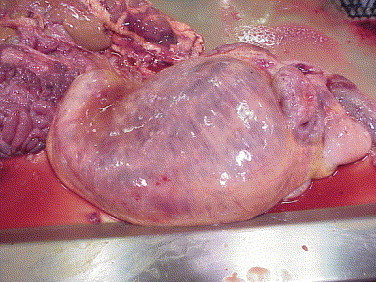

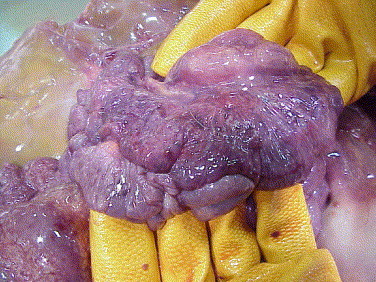

At necropsy, the calf had a distended rumen and abomasum, and the contents were a mixture of clotted milk and bloody fluid (Fig. 1 ). The abomasal and omasal walls were thickened and hemorrhagic. The duodenum 15 cm distal to the pyloris was hemorrhagic and emphysematous (Fig. 2 ), and the intestine contained blood-tinged fluid (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 1.

Subserosal edema along lesser curvature of rumen, with serosal ecchymoses and congestion in rumen wall.

Fig. 2.

Hemorrhage and emphysema in duodenum, with serosal ecchymoses.

Fig. 3.

Subserosal emphysema in spiral colon, with congestion and mucosal hemorrhage.

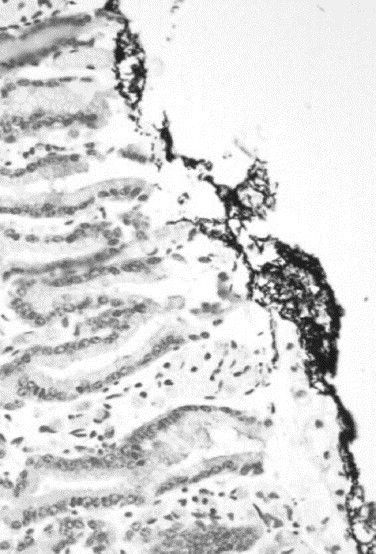

Microscopic examination of abomasum, rumen, and omasum revealed acute necrotizing hemorrhagic inflammation of the mucosa, with emphysema of the stomach wall. Duodenal lesions included acute necrotizing enteritis with hemorrhage, emphysema, and edema. Many large bacterial rods, which were morphologically compatible with clostridia, were found in the gut lumen and associated with the mucosal surface (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Gram-positive rods associated with the duodenal mucosal surface.

Direct fecal smears were negative for cryptosporidia, as were fluorescent antibody tests and electron microscopic examination for rotavirus and bovine coronavirus. Bacteriologic examination yielded heavy growth of C. perfringens from abomasal wall, abomasal content, and duodenal wall, and PCR genotyping revealed that these isolates were type A. Other bacterial pathogens associated with enteritis were not isolated.

3. Discussion

Taken together, these findings suggest a diagnosis of clostridial abomasitis. Signs and lesions are in keeping with those described by others [3], [4], [35], [36], observed in numerous natural cases in calves, and reproduced experimentally ([35], our unpublished findings). Bacteriologic culture and genotyping ruled out C. perfringens type C infection, as well as infection by other bacteria known to cause neonatal enteritis in calves.

Relatively little is known about the etiology of these cases, beyond the experimentally confirmed participation of C. perfringens type A ([35], our unpublished observations). However, dietary issues, such as overfeeding, feeding of barely thawed or contaminated colostrum, or conditions which effect decreased gut motility, probably contribute to occurrence of disease. This is supported by the elevated risk of type A hemorrhagic enteritis and sudden death in veal calves at specific times during the feeding period (our unpublished observations, Marie Archambault, personal communication).

Strains of type A are found normally in the intestine, even in neonates, and some contend that isolation of these organisms from calves with enteritis should not be given etiologic significance. However, it is useful to view this from the perspective that types B–E are defined by production of beta, epsilon, and iota toxins, while type A is a repository for all those strains which do not produce these toxins. Insufficient attention has been given to the possible action of alpha toxin in the gut. Furthermore, production of other potential virulence factors might set apart groups of isolates associated with specific syndromes which are now considered to be idiopathic. It is also possible that strains normally resident in the gut produce the observed infections, when anarchic multiplication follows nutrient spillover into upper small intestine.

There is little concrete information on the pathogenesis of type A enteric infections in calves. Disease is sometimes compatible with the action of a hemolytic toxin in the circulation, causing intravascular hemolysis and capillary damage, inflammation, platelet aggregation, shock, and sometimes-fatal cardiac effects [6], [37]. Alpha toxin can sometimes be found in the intestinal contents of animals with naturally occurring enteric disease, and is an important factor in pathogenesis of myonecrosis [30]. Little is known of the permeability of the intestine to alpha toxin, but it may be a virulence factor in cases of presumed enterotoxemia [1], [34]. The recently described beta2 toxin [38] may participate in pathogenesis of bovine enteric infections [39]. However, our findings suggest that only 14.3% (8/56) of isolates from calves with a similar syndrome were cpb2 positive, and only 50% of these express CPB2 (our unpublished results).

The case presented here is illustrative, in part, of the extraordinary versatility of C. perfringens as a pathogen. C. perfringens-induced disease manifests itself in multiple organ systems in multiple species, whether by virtue of virulence attributes specific for each situation or expression of attributes present in most, if not all, strains. Bovine neonatal hemorrhagic abomasitis and enteritis occurs in the face of vaccination against infections by types C and D, and, beyond alpha toxin, type A strains present few targets for immunoprophylaxis. The most prominent needs at present are consistent reproduction of the disease, elucidation of virulence attributes, and development and application of prevention and control strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Connie Gates, Jane Christopher-Hennings, and Dawn M. Bueschel. Supported in part by funds from Boehringer-Ingelheim Vetmedica and USDA-Hatch.

References

- 1.Daube G., Simon P., Limbourg B., Renier K., Kaeckenbeeck A. Molecular typing of Clostridium perfringens. Ann Med Vet. 1994;138:183–191. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jubb K.V.F., Kennedy P.C., Palmer N. 4th edn. vol. 2. Academic Press; London: 1993. (Pathology of domestic animals). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills K.W., Johnson J.L., Jensen R.L., Woodard L.F., Doster A.R. Laboratory findings associated with abomasal ulcers/tympany in range calves. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1990;2:208–212. doi: 10.1177/104063879000200310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roeder B.L., Chengappa M.M., Nagaraja T.G., Avery T.B., Kennedy G.A. Isolation of Clostridium perfringens from neonatal calves with ruminal and abomasal tympany abomasitis and abomasal ulceration. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1987;190:1550–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders G. Diagnosing braxy in calves and lambs. Vet Med. 1986;81:1050–1052. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timoney J.F., Gillespie J.H., Scott F.W., Barlough J.E. Comstock Publishing Associates; Ithaca NY: 1988. Hagan and Bruner's microbiology and infectious diseases of domestic animals. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackinnon J.D. Enterotoxaemia caused by Clostridium perfringens type C. Pig Vet J. 1989;22:119–125. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakabayashi D., Ogino H., Watanabe T., Nabeya M., Murayama J., Ishikawa M. Serological survey of Clostridium perfringens type A infection in cattle using an indirect haemagglutination test. J Vet Med Japan. 1990;43:593–597. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tominaga K., Takeya G., Okada K. A first case report in Yamaguchi prefecture of the outbreak of haemorrhagic enteritis necroticans of dairy cattle caused by Clostridium perfringens type A. Yamaguchi J Vet Med. 1984;11:71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arbuckle J.B.R. The attachment of Clostridium welchii (Cl. perfringens) type C to intestinal villi of pigs. J Pathol. 1972;106:65–72. doi: 10.1002/path.1711060202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johannsen U., Menger S., Erwerth W., Köhler B. Clostridium perfringens type C enterotoxemia (necrotizing enteritis) of suckling piglets. 3. Light and electron microscopic investigations on the pathology and pathogenesis of experimental Clostridium perfringens type C infection. Arch Exp Veterinarmed. 1986;40:895–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johannsen U., Menger S., Erwerth W., Köhler B. Clostridium perfringens type C enterotoxemia (necrotizing enteritis) of suckling piglets. 2. Light and electron microscopic studies on the pathology and pathogenesis of experimental Clostridium perfringens type C intoxication. Arch Exp Veterinarmed. 1986;40:881–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johannsen U., Erwerth W., Kunz G., Köhler B. Clostridium perfringens type C enterotoxemia (necrotizing enteritis) of suckling piglets. 1. Attempts at experimental induction of disease by Clostridium perfringens type C intoxication and infection. Arch Exp Veterinarmed. 1986;40:811–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubo M., Watase H. Electron microscopy of Clostridium perfringens in the intestine of neonatal pigs with necrotic enteritis. Jpn J Vet Sci. 1985;47:497–501. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.47.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks M.E., Sterne M., Warrack G.H. A reassessment of the criteria used for type differentiation of Clostridium perfringens. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1957;74:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niilo L. Clostridium perfringens type C enterotoxemia. Can Vet J. 1988;29:658–664. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergeland M.E. Clostridial infections. In: Leman A.D., Glock R.D., Mengeling R.W., Penny R.H.C., Scholl E., Straw B., editors. Diseases of swine. 5th edn. ISU Press; Ames, IA: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niilo L. Experimental production of hemorrhagic enterotoxemia by Clostridium perfringens type C in maturing lambs. Can J Vet Res. 1986;50:32–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffin J.F.T. Acute bacterial infections in farmed deer. Ir Vet J. 1987;41:328–331. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schamber G.J., Berg I.E., Molesworth J.R. Braxy or bradsot-like abomasitis caused by Clostridium septicum in a calf. Can Vet J. 1986;27:194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith L. The pathogenic anaerobic bacteria. 2nd edn. C.C. Thomas; Springfield, IL: 1975. Clostridium perfringens; pp. 115–176. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis T.M., Rowe J.B., Lloyd J.M. Acute abomasitis due to Clostridium septicum infection in experimental sheep. Aust Vet J. 1983;60:308–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1983.tb02817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballard J., Bryant A., Stevens D., Tweten R.K. Purification and characterization of the lethal toxin (alpha-toxin) of Clostridium septicum. Infect Immun. 1992;60:784–790. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.784-790.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballard J., Sokolov Y., Yuan W.L., Kagan B.L., Tweten R.K. Activation and mechanism of Clostridium septicum alpha toxin. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:627–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleming S. Enterotoxemia in neonatal calves. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 1985;1:509–514. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0720(15)31299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGowan G., Moulton J.E., Rood S.E. Lamb losses associated with Clostridium perfringens type A. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1958;133:219–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johannsen U., Arnold P., Köhler B., Selbitz H.J. Studies into experimental Clostridium perfringens type A enterotoxaemia of suckled piglets: experimental provocation of the disease by Clostridium perfringens type A intoxication and infection. Monatsh für Veterinaermed. 1993;48:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johannsen U., Menger S., Arnold P., Köhler B., Selbitz H.J. Experimental Clostridium perfringens type A enterotoxaemia in unweaned piglets. II. Light- and electron-microscopic investigations on the pathology and pathogenesis of experimental C. perfringens type A infection. Monatsh für Veterinarmed. 1993;48:299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johannsen U., Menger S., Arnold P., Köhler B., Selbitz H.J. Experimental Clostridium perfringens type A enterotoxaemia in unweaned piglets. Monatsh für Veterinarmed. 1993;48:267–273. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Awad M.M., Bryant A.E., Stevens D.L., Rood J.I. Virulence studies on chromosomal alpha-toxin and theta-toxin mutants constructed by allelic exchange provide genetic evidence for the essential role of alpha-toxin in Clostridium perfringens-mediated gas gangrene. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:191–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginter A, Williamson ED, Dessy F, Coppe P, Fearn A, Titball RW. Comparison of the a-toxin produced by bovine enteric and gas gangrene strains of C. perfringens. International conference on the molecular genetics and pathogenesis of the clostridia, 1995. Abstract A17. p. 19.

- 32.Rose A.L., Edgar O. Enterotoxaemic jaundice of cattle and sheep. A preliminary report on the aetiology of the disease. Aust Vet J. 1936;12:212–220. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoo H.S., Lee S.U., Park K.Y., Park Y.H. Molecular typing and epidemiological survey of prevalence of Clostridium perfringens types by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:228–232. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.228-232.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daube G., China B., Simon P., Hvala K., Mainil J. Typing of Clostridium perfringens by in vitro amplification of toxin genes. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;77:650–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb02815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roeder B.L., Changappa M.M., Nagaraja T.G., Avery T.B., Kennedy G.A. Experimental induction of abomasal tympany, abomasitis, and abomasal ulceration by intraruminal inoculation of Clostridium perfringens type A in neonatal calves. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:201–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lulov R., Angelov R.K. Enterotoxemia in newborn calves due to Cl. perfringens types A, C and D. Vet Med Nauki. 1986;23:20–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens D.L., Troyer B.E., Merrick D.T., Mitten T.E., Olson R.D. Lethal effects and cardiovascular effects of purified alpha and theta toxins. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:272–279. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibert M., Jolivet-Reynaud C., Popoff M.R., Jolivet-Renaud C. Beta2 toxin, a novel toxin produced by Clostridium perfringens. Gene. 1977;203:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00493-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manteca C., Daube G., Pirson V., Limbourg B., Kaeckenbeeck A., Mainil J.G. Bacterial intestinal flora associated with enterotoxaemia in Belgian Blue calves. Vet Microbiol. 2001;81:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(01)00329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]