Abstract

The aim of this study was to report two cases of Clostridium perfringens type A and Clostridium difficile co-infection in adult dogs. Both animals were positive for A/B toxin. Toxigenic C. difficile and C. perfringens type A positive for NetE and NetF-encoding genes were isolated. This report reinforces the necessity of studying a possible synergism of C. difficile and C. perfringens in enteric disorders.

Keywords: Necrotic enteritis, Zoonosis, Bloody diarrhea

Clostridium perfringens type A and Clostridium difficile are commonly described as enteropathogens in dogs. However, the role of both agents remains incompletely characterized, and diagnoses of these infections are still a challenge. Regarding C. perfringens type A, the high prevalence of enterotoxin-encoding gene cpe in diarrheic dogs led to a suspicion that this additional virulence factor was responsible for the pathogenesis of canine C. perfringens-associated diarrhea. However, several studies have failed to confirm this hypothesis [11]. Recently, three pore-forming toxins (NetE, NetF and NetG) that are always present in C. perfringens type A cpe + strains were described in association with fatal canine hemorrhagic gastroenteritis [2]. Until now, the study by Gohari was the only study in the literature on this topic. Thus, the predisposing factors and occurrence of this disease remain unclear.

The role of C. difficile in canine diarrhea is also incompletely characterized. Nonetheless, there are reports of chronic and acute diarrhea caused by A/B toxins of C. difficile. However, it remains unclear whether C. difficile is the primary or secondary agent that causes diarrhea in dogs [17], [7]. In addition, several studies showed a high similarity between C. difficile isolates from humans and animals, suggesting a possible zoonotic transmission [3].

Despite the known importance of both enteropathogens, there are no descriptions of co-infection of these two Clostridium species in dogs. Thus, the aim of this study was to report two cases of C. perfringens and C. difficile co-infection in adult dogs.

An 18-month-old male German Shepherd (dog 1) was presented to the Veterinary Hospital of Federal University of Minas Gerais (Belo Horizonte city, Brazil) with a history of bloody diarrhea for two days. The dog was fed a regular commercial diet, had no history of other diseases in the past few months and was up-to-date on vaccinations and deworming. During the clinical examination, a stool sample was collected directly from the rectum for a differential diagnosis of the most common enteropathogens in dogs. The animal was treated with trimethoprim/sulfadiazine, omeprazole and fluid therapy. On the second day after admission, there was no blood in the feces, but the animal was still diarrheic. The consistency of the fecal material gradually returned to solid with a normal odor. The animal was discharged from the Veterinary Hospital five days after admission.

The second dog (dog 2) was a 12-year-old, mixed breed female. Similar to dog 1, this animal was also fed a regular commercial diet, had no history of other diseases and was up-to-date on vaccinations and deworming. The owner reported a history of bloody diarrhea for two days. During the clinical examination, the animal was apathetic and severely dehydrated. The dog died a few minutes after admission while receiving fluid therapy. During the post mortem examination, the intestinal contents from the small intestine were collected. Fragments of this organ were sampled in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. After fixation, specimens were routinely processed for histopathology, sectioned to 4 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

The stool sample of dog 1 and the intestinal contents of dog 2 were submitted to the following laboratory exams: rotavirus detection by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by silver staining [4]; parvovirus, rotavirus, coronavirus and Giardia lamblia detection by a chromatographic immunoassay (Ecodiagnostica, Brazil); isolation and genotyping of C. difficile [15] and C. perfringens [12], [2], [19]; C. perfringens enterotoxin detection by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (EIA) kit (RIDASCREEN® C. perfringens Enterotoxin - R-Biopharm, Germany); C. difficile A/B toxin detection by ELISA (C. difficile Tox A/B II - Techlab Inc., USA); culture for Salmonella spp. in Hektoen Enteric Agar and XLT4 agar (Biobrás®, Prodimol Biotechnology); isolation of Escherichia coli in MacConkey agar (Biobrás®, Prodimol Biotechnology), followed by a previously described PCR method [8] to investigate the following virulence factor genes: eae, stx1, stx2, ehxA, aggR, ipaH, eltA, etlB, est, and stap.

Both dogs had positive C. perfringens and C. difficile isolations and A/B toxins detection. However, they were negative for C. perfringens enterotoxin by the EIA. E. coli was also isolated, but all strains were negative for virulence factors by PCR. All other exams were negative. Therefore, the involvement of Giardia spp., Salmonella spp., rotavirus, coronavirus and parvovirus was ruled out.

C. perfringens strains were genotyped as type A and positive for cpe, netE and netF in both cases. Interestingly, the C. perfringens isolate from dog 1 was also positive for netG. Both C. difficile isolates were positive for toxin A- and toxin B-encoding genes (tcdA and tcdB) but negative for binary toxin gene (cdtB). PCR ribotyping was conducted as previously described [5]. Both strains were identified as 014/020. Table 1 summarizes the laboratory findings from both dogs.

Table 1.

Details of the two adult dogs with Clostridium perfringens type A and Clostridium difficile co-infection.

| Dog | Age |

Clostridium perfringens |

Clostridium difficile |

Outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotypinga | EIA (CPE) | Isolation | Ribotyping | EIA (A/B) | |||

| 1 | 1.5 years | cpe+netE+netF+netG+ | – | A+B+CDT- | 014/020 | + | Recovered |

| 2 | 12 years | cpe+netE+netF+ | – | A+B+CDT- | 014/020 | + | Death |

Both C. perfringens isolates were also negative for netB, tpeL and cpb2.

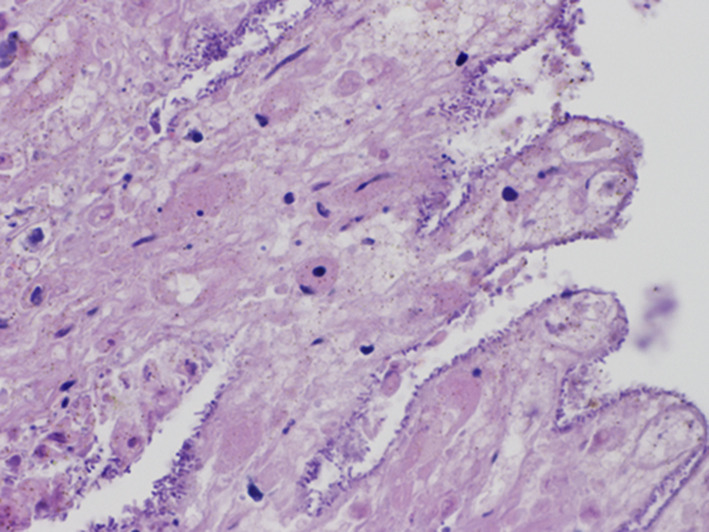

During the post mortem examination of dog 2, the small intestine was distended by a hemorrhagic fluid and gas content, with markedly reddish serosa (congestion). The mucosal surface was diffusely red and covered with reddish and viscous material. The microscopic evaluation was limited by autolysis of the organ. However, evidence of necrosis of the villi and hemorrhage in the lamina propria and intestinal lumen were observed. Numerous Gram positive rods were attached to the luminal surface of the denuded villi (Fig. 1 ). The lamina propria and submucosa were mildly expanded by edema, and the blood vessels of the submucosa were markedly congested.

Fig. 1.

Dog 2 – Duodenum. Large numbers of clostridia-like bacilli attached to the necrotic villi.

To clarify whether dog 1 was permanently colonized by a C. perfringens cpe + netE + netF + netG + strain, a new stool sample was collected approximately eight months after the diarrhea episode. This second stool sample was positive for C. perfringens type A, but the isolated strain was negative for cpe, netE, netF and netG.

Gohari et al. [2] described an association of these three new C. perfringens pore forming toxins (NetE, NetF and NetG) in fatal cases of canine hemorrhagic diarrhea. Both dogs in the present report presented at a Veterinary Hospital with bloody diarrhea, but dog 1 recovered completely after a 3-day treatment. Despite the bloody diarrhea, this animal was clinically healthy and not severely dehydrated during the clinical examination. In contrast to the previous report by [2]; our findings suggest that a C. perfringens infection might be involved in less dramatic cases of hemorrhagic enteritis.

In contrast, the acute clinical evolution experienced by dog 2 and the post mortem findings corroborate the observations described in acute canine C. perfringens type A-associated diarrhea [17], [7], [9]. Regardless, comparisons of clinical evolution are still limited. This is only the second study on C. perfringens netE positivity in dogs. In the first description of this condition, the authors did not provide clinical details of the affected animals [2]. Some studies suggest that changes in feed is an important predisposing factor to trigger a C. perfringens type A infection in dogs and other species [7], [11]. According to the owners, both dogs in the present case report were only fed a commercial diet. The absence of a known diet alteration or any other relevant predisposing factor corroborates the only study available thus far on C. perfringens netE positivity in dogs [2] and highlights the need for additional studies on this matter.

Both dogs were also positive for A/B toxins, and toxigenic strains were isolated, which suggested the involvement of C. difficile. Both strains were identified with PCR as ribotype 014/020, which is recognized as one of the most common causes of C. difficile infection (CDI) in the European community. It also has been previously described in dogs in several countries [6], [18]. In Brazil, ribotype 014/020 was previously reported in several animal species, including domestic and wild animals, and also in humans with confirmed CDI [1], [10], [13], [14].

C. perfringens infection in adult dogs is commonly linked to food or environmental changes, but no marked changes were reported by the owners in both cases described here. Specifically for C. difficile, antibiotic therapy is well known as the most common predisposing factor for CDI. However, in the present report, neither dog received any antibiotics before being sampled [16]. described five cases of C. perfringens type C and C. difficile co-infection in foals. Similar to the two cases described here, none of the affected foals were on antibiotic therapy. In light of this, the authors suggested that the C. perfringens infection may have acted as a predisposing factor for C. difficile or vice versa. Anyway, Together, these two reports reinforce the need to study a possible synergism of C. perfringens and C. difficile in enteric disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from Fapemig, Capes, CNPq and PRPq-UFMG. Juan Josue Puño-Sarmiento and Prof. Gerson Nakazato are acknowledged for contribution with the E. coli controls. M. Rupnik laboratory (NLZOH, Maribor) is acknowledged for confirmation of C. difficile ribotype.

References

- 1.Balassiano I.T., Miranda K.R., Boente R.F., Pauer H., Oliveira I.C., Santos-Filho J., Amorim E.L., Caniné G.A., Souza C.F., Gomes M.Z., Ferreira E.O., Brazier J.S., Domingues R.M. Characterization of Clostridium difficile strains isolated from immunosuppressed inpatients in a hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Anaerobe. 2009 Jun;15(3):61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gohari I.M., Parreira V.R., Nowell V.J., Nicholson V.M., Oliphant K., Prescott J.F. A Novel pore-forming toxin in type A Clostridium perfringens is associated with both fatal canine hemorrhagic gastroenteritis and fatal foal Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Pone. 2015:1–27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hensgens M.P., Keessen E.C., Squire M.M., Riley T.V., Koene M.G., de Boer E., Lipman L.J., Kuijper E.J. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Study Group for Clostridium difficile (ESGCD). Clostridium difficile infection in the community: a zoonotic disease? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012 Jul;18(7):635–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herring A.J., Inglis N.F., Ojeh C.K., Snodgrass D.R., Menzies J.D. Rapid diagnosis of rotavirus infection by direct detection of viral nucleic acid in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1982;16:473–477. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.3.473-477.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janezic S., Rupnik M. Molecular typing methods for Clostridium difficile: pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and PCR ribotyping. In: Mullany P., Roberts A., editors. Walker JM, Series Ed. vol. 646. Humana Press; 2010. pp. 55–66. (Clostridium difficile, Methods and Protocols; Springer Protocols – Methods in Molecular Biology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koene M.G., Mevius D., Wagenaar J.A., Harmanus C., Hensgens M.P., Meetsma A.M., Putirulan F.F., van Bergen M.A., Kuijper E.J. Clostridium difficile in Dutch animals: their presence, characteristics and similarities with human isolates. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012 Aug;18(8):778–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marks S.L., Rankin S.C., Byrne B.A., Weese J.S. Enteropathogenic bacteria in dogs and cats: diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment, and control. J. Vet. Intern Med. 2011 Nov-Dec;25(6):1195–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puño-Sarmiento J., Medeiros L., Chiconi C., Martins F., Pelayo J., Rocha S., Blanco J., Blanco M., Zanutto M., Kobayashi R., Nakazato G. Detection of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from dogs and cats in Brazil. Vet. Microbiol. 2013 Oct 25;166(3–4):676–680. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.07.007. Epub 2013 Jul 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlegel B.J., Van Dreumel T., Slavić D., Prescott J.F. Clostridium perfringens type A fatal acute hemorrhagic gastroenteritis in a dog. Can. Vet. J. 2012 May;53(5):555–557. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Secco D.A., Balassiano I.T., Boente R.F., Miranda K.R., Brazier J., Hall V., dos Santos-Filho J., Lobo L.A., Nouér S.A., Domingues R.M. Clostridium difficile infection among immunocompromised patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and detection of moxifloxacin resistance in a ribotype 014 strain. Anaerobe. 2014 Aug;28:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva R.O., Lobato F.C. Clostridium perfringens: a review of enteric diseases in dogs, cats and wild animals. Anaerobe. 2015 Jun;33:14–17. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva R.O., Ribeiro M.G., Palhares M.S., Borges A.S., Maranhão R.P., Silva M.X., Lucas T.M., Olivo G., Lobato F.C. Detection of A/B toxin and isolation of Clostridium difficile and Clostridium perfringens from foals. Equine Vet. J. 2013 Nov;45(6):671–675. doi: 10.1111/evj.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva R.O., Rupnik M., Diniz A.N., Vilela E.G., Lobato F.C. Clostridium difficile ribotypes in humans and animals in Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2015 Dec;110(8):1062–1065. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760150294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva R.O.S., Almeida L.R., Oliveira Junior C.A., Soares D.F.M., Pereira P.L.L., Kocuvan A., Rupnik M., Lobato F.C.F. Carriage of Clostridium difficile in free-living South American coati (Nasua nasua) in Brazil. Anaerobe. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva R.O.S., Salvarani F.M., Cruz Júnior E.C.C., Pires P.S., Santos R.L.R., Assis R.A., Guedes R.M.C., Lobato F.C.F. Detection of enterotoxin A and cytotoxin B, and isolation of Clostridium difficile in piglets in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Ciência Rural. 2011;41:1130–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uzal F.A., Diab S.S., Blanchard P., Moore J., Anthenill L., Shahriar F., Garcia J.P., Songer J.G. Clostridium perfringens type C and Clostridium difficile co-infection in foals. Vet. Microbiol. 2012 May 4;156(3–4):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.11.023. Epub 2011 Dec 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weese J.S. Bacterial enteritis in dogs and cats: diagnosis, therapy, and zoonotic potential. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2011;41:287–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wetterwik K.J., Trowald-Wigh G., Fernström L.L., Krovacek K. Clostridium difficile in faeces from healthy dogs and dogs with diarrhea. Acta Vet. Scand. 2013;55(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-55-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keyburn A.L., Boyce J.D., Vaz P., Bannam T.L., Ford M.E., Parker D., Di Rubbo A., Rood J.I., Moore R.J. NetB, a new toxin that is associated with avian necrotic enteritis caused by Clostridium perfringens. PLoS Pathog. 2008 Feb 8;4(2):e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]