Abstract

Background

There is a critical need to develop valid, non-invasive biomarkers for Parkinsonian syndromes. The current 17-site, international study assesses whether non-invasive diffusion MRI (dMRI) can distinguish between Parkinsonian syndromes.

Methods

We used dMRI from 1002 subjects, along with the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III (MDS-UPDRS III), to develop and validate disease-specific machine learning comparisons using 60 template regions and tracts of interest in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space between Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Atypical Parkinsonism (multiple system atrophy – MSA, progressive supranuclear palsy – PSP), as well as between MSA and PSP. For each comparison, models were developed on a training/validation cohort and evaluated in a test cohort by quantifying the area under the curve (AUC) of receiving operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Findings

In the test cohort for both disease-specific comparisons, AUCs were high in the dMRI + MDS-UPDRS (PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism: 0·962; MSA vs. PSP: 0·897) and dMRI Only (PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism: 0·955; MSA vs. PSP: 0·926) models, whereas the MDS-UPDRS III Only models had significantly lower AUCs (PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism: 0·775; MSA vs. PSP: 0·582).

Interpretations

This study provides an objective, validated, and generalizable imaging approach to distinguish different forms of Parkinsonian syndromes using multi-site dMRI cohorts. The dMRI method does not involve radioactive tracers, is completely automated, and can be collected in less than 12 minutes across 3T scanners worldwide. The use of this test could thus positively impact the clinical care of patients with Parkinson’s disease and Parkinsonism as well as reduce the number of misdiagnosed cases in clinical trials.

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD), multiple system atrophy (MSA), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) are neurodegenerative disorders that are challenging to differentiate because of shared and overlapping motor and non-motor features (1–3). Accordingly, misdiagnosis of PD, MSA, and PSP is high, especially early in disease. Diagnosis accuracy in early PD (<5 years duration) is approximately 58%, and 54% of misdiagnosed patients have MSA or PSP (3–7). Whereas dopamine transporter imaging can identify the nigrostriatal denervation that leads to dopaminergic deficiency, it cannot distinguish between the different forms of Parkinsonism since they all exhibit this characteristic (8). The lack of a clinically reliable non-invasive biomarker to distinguish different Parkinsonian syndromes is a major hindrance to improved diagnosis accuracy and therefore better categorization in clinical trials; however, diffusion MRI shows particular promise in addressing this shortfall.

Diffusion MRI (dMRI) is a promising technique because it facilitates in vivo quantification of brain microstructure associated with histology using a measure called fractional anisotropy (FA) (9). However, FA can be susceptible to partial volume effects, as there is both tissue and fluid contained in its calculation. Recent work using a single site cohort has shown that free-water imaging, a method which allows for the separation of the fluid (i.e., free-water (FW)) and tissue (FW-corrected FA (FAT)) components in dMRI can detect unique microstructural changes in different forms of Parkinsonism (10). Several studies have been performed in Parkinsonian patients showing elevated FW within the posterior substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease and in widespread, yet distinct, networks in MSA and PSP (10). While these studies show promise for detecting objective and unique diffusion measurements in Parkinsonism, they used manual region delineation, small cohorts, and dMRI data acquired from only one MRI scanner. Development of a fully automated, generalizable procedure that differentiates Parkinsonian syndromes by utilizing diffusion measurements from pathologically relevant regions is a critical need for the field.

The goal of this study was to create and validate an objective and generalizable biomarker to differentiate Parkinsonian syndromes. To accomplish this goal, we measured FW and FAT in 17 regions and 43 white matter tracts relevant to Parkinsonism in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space in an internationally derived dataset collected on 17 different 3T MRI scanners. At each site, the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III (MDS-UPDRS III) was also collected. We then developed rigorous disease-specific machine learning comparisons, including PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism, and MSA vs. PSP. Using these comparisons, we tested the ability of three different models (dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III, dMRI Only, MDS-UPDRS III Only) to differentiate forms of Parkinsonism in a test cohort. Importantly, all models were created without the inclusion of a site covariate so that the models are generalizable to sites not included in the present study. Comparisons were made between models to determine if dMRI outperformed the MDS-UPDRS III in the classification of disease state.

METHODS

Participants and Diffusion MRI Acquisition

This study used 1002 individuals obtained from 8 different cohorts using 17 different MRI scanners and included 278 healthy controls, 511 PD, 84 MSA, and 129 PSP subjects (Table I). Subjects with Parkinsonism were diagnosed by a movement disorder specialist at their respective site using standard diagnostic criteria (1, 2, 7, 11). There are multiple phenotypes of MSA, including Parkinsonian (MSAp) and cerebellar (MSAc). A majority (95·24%) of our MSA cohort had MSAp. All PSP subtypes were included, but we did not delineate subtypes. The controls reported no history of neuropsychiatric or neurological problems. Disease severity was assessed using the MDS-UPDRS III or the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). UPDRS scores were converted to MDS-UPDRS scores using established guidelines (12). Participants provided written consent for all procedures, which were approved by Institutional Review Boards.

TABLE I.

Demographic and Scanner Information for the 8 Cohorts used in this Study. Abbreviations: yrs, years; M, male; F, female; CON, control; PD, Parkinson’s disease; MSA, multiple system atrophy; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TR; repetition time; UF1, University of Florida cohort 1; UF2, University of Florida cohort 2; PSHMC, Penn State Hershey Medical Center; MUI, Medical University Innsbruck; NW, Northwestern University; UM, University of Michigan; PPMI, Parkinson’s Progression Marker’s Initiative; 4RTNI, 4 Repeat Tauopathy Neuroimaging Initiative Cohort. As the PPMI cohort had variable TR times, the median is reported. Data was obtained in 3 different countries. Data are represented as mean (standard deviation) where appropriate.

| Cohort | UF1 | UF2 | PSHMC | MUI | NW | UM | PPMI | 4RTNI | Total/Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | 169 | 100 | 104 | 180 | 55 | 206 | 150 | 38 | 1002 |

| Control/PD/MSA/PSP | 46/59/32/32 | 11/72/9/8 | 36/35/15/18 | 48/91/20/21 | 12/24/7/12 | 76/130/-/- | 49/100/1/- | -/-/-/38 | 278/511/84/129 |

| Age (yrs) | 65·24 (9·20) | 65·22 (7·92) | 70·68 (8·15) | 63·46 (10·57) | 67·25 (7·58) | 65·61 (9·34) | 59·96 (9·69) | 69·76 (7·60) | 65·05 (9·65) |

| Sex (M/F) | 98/71 | 58/42 | 68/36 | 106/74 | 30/25 | 130/76 | 99/51 | 19/19 | 608/394 |

| Start of Accrual Date (MM/DD/YY) | 01/31/12 | 04/13/17 | 11/24/09 | 07/27/11 | 11/16/17 | 12/09/08 | 10/27/10 | 06/21/11 | - |

| End of Accrual (MM/DD/YY) | 09/18/14 | 11/29/18 | 08/25/15 | 04/04/13 | 11/29/18 | 06/18/14 | 05/28/13 | 12/15/14 | - |

| Control Disease Duration (yrs) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| PD Disease Duration (yrs) | 3·22 (2·34) | 2·56 (2·39) | 3·37 (3·61) | 6·02 (4·27) | 4·05 (2·44) | 6·00 (4·21) | 0·60 (0·59) | - | 3·87 (3·84) |

| MSA Disease Duration (yrs) | 3·73 (3·05) | 2·17 (1·49) | 3·60 (3·27) | 2·03 (2·26) | 1·86 (1·85) | - | 0·20 | - | 2·94 (2·77) |

| PSP Disease Duration (yrs) | 3·15 (2·95) | 2·15 (1·59) | 2·83 (2·53) | 1·74 (1·22) | 3·60 (3·13) | - | - | 5·22 (3·88) | 3·45 (3·16) |

| Control MDS-UPDRS III | 3·07 (2·82) | 6·00 (3·10) | 6·08 (7·59) | 3·00 (7·17) | 2·92 (1·38) | 4·34 (4·96) | 0·35 (0·69) | - | 3·42 (5·26) |

| PD MDS-UPDRS III | 26·19 (10·98) | 30·72 (11·68) | 38·17 (28·42) | 36·75 (12·59) | 31·00 (13·13) | 32·60 (14·27) | 19·9 (8·92) | - | 30·15 (15·02) |

| MSA MDS-UPDRS III | 46·25 (16·88) | 64·22 (14·00) | 49·60 (19·54) | 52·48 (10·97) | 59·71 (21·87) | - | - | - | 51·13 (17·17) |

| PSP MDS-UPDRS III | 45·19 (18·56) | 55·63 (19·40) | 45·44 (24·20) | 34·02 (18·10) | 46·67 (15·75) | - | - | 33·16 (17·42) | 40·65 (19·79) |

| Sites | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 17 |

| MRI Strength and Vendor | 3T Philips | 3T Siemens | 3T Siemens | 3T Siemens | 3T Siemens | 3T Philips | 3T Siemens | 3T Siemens | - |

| Directions | 64 | 64 | 42 | 20 | 64 | 15 | 64 | 41 | - |

| B-values (s/mm2) | 0,1000 | 0,1000 | 0,1000 | 0,1000 | 0,1000 | 0,800 | 0,1000 | 0,1000 | - |

| Resolution (mm x mm x mm) | 2 × 2 × 2 | 2 × 2 × 2 | 2 × 2 × 2 | 2 × 2 × 3 | 2 × 2 × 2 | 1·75 × 1·75 × 1·75 | 2 × 2 × 2 | 2·7 × 2·7 × 2·7 | - |

| TE (ms) | 86 | 58 | 82 | 83 | 58 | 67 | 86 | 82 | - |

| TR (ms) | 7748 | 6400 | 8300 | 8200 | 6400 | 8044 | 2223 | 9200 | - |

Diffusion MRI Data Preprocessing

FMRIB Software Library (FSL, http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/) and custom UNIX shell scripts were used to preprocess the data (13). Data preprocessing using custom MATLAB scripts was conducted for all datasets to obtain FW and FAT images for each individual (14). Preprocessing was identical to prior work from our group (10). Quality control was performed by visually inspecting each individual FW and FAT map. Subjects in which the field of view did not encompass the whole brain and/or there were distortions were not included in this study (<1% of the total data). Since partial brains and distortions were excluded from our analysis, there was no need to impute missing values for any region or tract used in the analysis.

Diffusion MRI Data Normalization to MNI Space

In this study, we performed a literature review and analysis (Supplemental Appendix) that determined an optimal, automated normalization pipeline for dMRI data. We compared FW values obtained from hand-drawn ROIs to template-derived FW values in a subset of patients from the University of Florida (n=104, including controls, PD, MSA, and PSP) using four different normalization pipelines. We found that using the Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) software provided the highest intraclass correlation coefficients between hand-drawn and template-derived FW values. Thus, FW and FAT were normalized using this automated pipeline for all subsequent analyses (15).

Regions of Interest

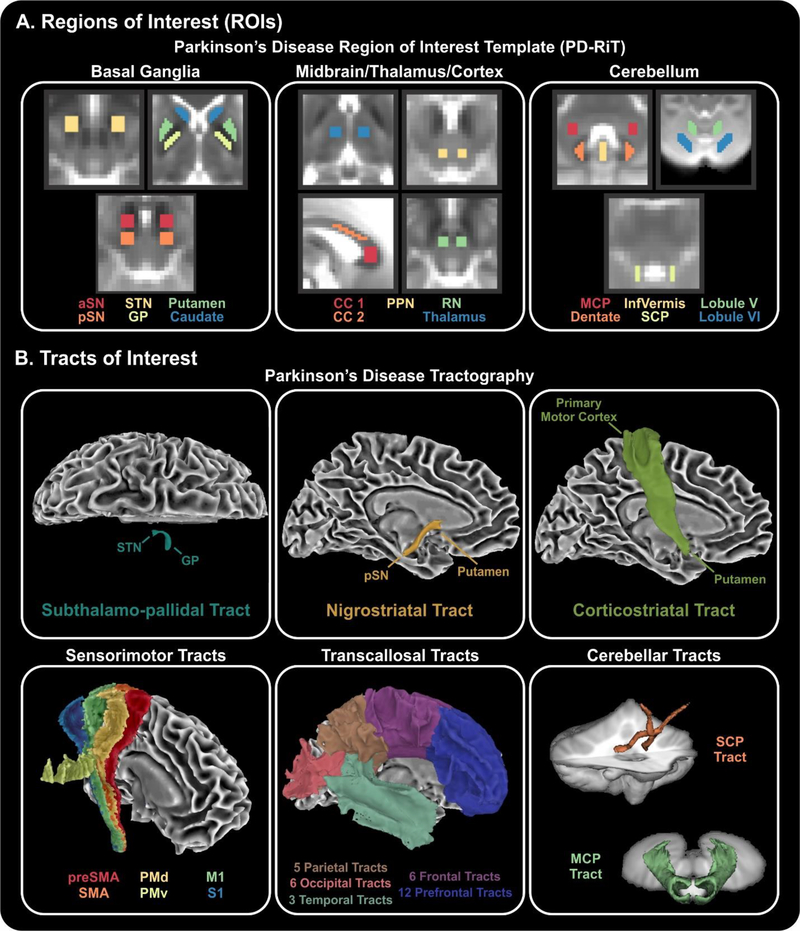

To perform this study, we created a Parkinson’s disease region of interest template in MNI space (Figure 1A), which includes 17 regions in the basal ganglia (anterior substantia nigra, posterior substantia nigra, subthalamic nucleus, globus pallidus, putamen, caudate nucleus), midbrain/thalamus/cortex (premotor corpus callosum, prefrontal corpus callosum, pedunculopontine nucleus, red nucleus, thalamus), and cerebellum (middle cerebellar peduncle, superior cerebellar peduncle, inferior vermis, dentate nucleus, cerebellar lobule V, cerebellar lobule VI).

Figure 1. Regions and tracts of interest.

(A) Regions of interest covered many areas of the basal ganglia (column 1), midbrain/thalamus/cortex (column 2), and cerebellum (column 3). (B) Tracts of interest included a subthalamo-pallidal tract, nigrostriatal tract, and corticostriatal tract, as well as 6 sensorimotor tracts from the S-MATT, 32 transcallosal tracts from the TCATT, and 2 cerebellar tracts. Abbreviations: aSN, anterior subtantia nigra; pSN, posterior subtantia nigra; STN, subthalamic nucleus; GP, globus pallidus; CC 1, prefrontal corpus callosum; CC 2, premotor corpus callosum; PPN, pedunculopontine nucleus; RN, red nucleus; MCP, middle cerebellar peduncle; InfVermis, inferior cerebellar vermis; SCP, superior cerebellar peduncle; preSMA, pre-supplemental motor area; SMA, supplemental motor area; PMd, dorsal premotor area; PMv, ventral premotor area; M1, primary motor cortex; S1, somatosensory cortex.

Tracts of Interest

A total of 43 white matter tracts were also used (Figure 1B). We conducted probabilistic tractography identically to our prior work using the Human Connectome Project dataset to characterize the subthalamo-pallidal, nigrostriatal, and corticostriatal tracts (16). We also incorporated several existing tractography templates, which include the sensorimotor area tract template (S-MATT) (16), the transcallosal tractography template (TCATT), and a cerebellar white matter atlas (17). The S-MATT includes 6 different sensorimotor tracts, including the tracts descending from the primary motor cortex, dorsal premotor cortex, ventral premotor cortex, supplemental motor area, pre-supplemental motor area, and somatosensory cortex. The TCATT includes 5 parietal, 6 occipital, 6 frontal, and 12 prefrontal commissural tracts (18). We also used the superior and middle cerebellar tracts from the cerebellar probabilistic white matter atlas (17). FW and FAT was calculated for each region and tract separately in each subject.

Machine Learning

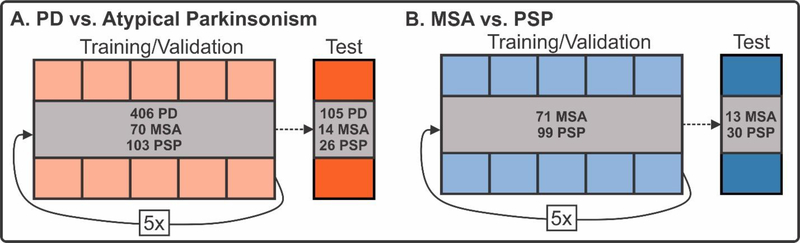

The variables available in this study include dMRI values (FW and FAT in 17 regions and 43 tracts), MDS-UPDRS III, sex, and age. Three different combinations of variables were created: (1) dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III, (2) dMRI Only, and (3) MDS-UPDRS III Only. Age and sex were included in all analyses as these are variables that would be readily available for input in regular practice. dMRI variables include FW and FAT values in each region and tract, resulting in a total of 60 FAT measurements and 60 FW measurements for each individual. Each combination of variables was used in the training and validation of a support vector machine (SVM) learning algorithm using a linear kernel in the scikit-learn package in Python (19). We chose the support vector machine (SVM) because it is a widely accepted and robust machine learning model for classification. Compared to recent deep learning methods such as convolutional neural networks (CNN) and conventional machine learning algorithms such as decision trees and random forests, SVM has the advantage of high performance at low computational cost. It also does not need a large amount of labeled data. SVM works by separating the data using a hyperplane in the feature space. A linear kernel indicates that the data points are represented using its original feature space, instead of being projected into a high-dimensional space for classification. We chose to use a linear kernel as it the data in this study was able to be linearly separated with good performance. Further, the development of SVM models using a linear kernel allowed us to extract the coefficient of each ROI and tract to determine its importance in the model. Other more complex kernels, such as polynomial and radial basis function kernels, increased the computational time required to train the models and did not provide additional accuracy. Disease-specific comparisons were made to predict diagnosis (PD vs. Atypical and MSA vs. PSP). Training/validation sets for each disease-specific comparison consisted of 80% of the total relevant data while the remaining 20% was reserved for a test dataset. Subjects were randomly assigned to the training/validation set or the test dataset using stratified sampling to ensure that the training/validation and test dataset group proportions were equal to the total dataset group proportions (Figure 2). In the training/validation cohort, the data was randomly split into 5 subgroups for 5 fold cross-validation. The purpose of the 5 fold cross-validation was to optimize the F1 score (i.e., the harmonic mean of the precision and recall) by optimizing the penalty parameter (C, a measure which directly represents the tolerance for error) across the 5 distinct folds. This penalty parameter was used to train the machine learning model using the training/validation dataset and the performance of this optimized model was evaluated on the test dataset.

Figure 2. Machine learning procedure.

The PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism (A) and MSA vs. PSP (B) comparisons were first split into training/validation (80%) and test (20%) cohorts using random sampling. Five-fold cross-validation was conducted independently for both comparisons to tune the hyperparameters in the support vector machine learning analysis. Following hyperparameter tuning, this model was applied to the test cohort to evaluate performance.

To evaluate the performance of the machine learning models in the training/validation cohort and the test cohort, we conducted receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses using the trained models. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for each model (dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III, dMRI Only, MDS-UPDRS III Only) for each comparison (PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism and MSA vs. PSP). The models were statistically evaluated using Delong’s test to compare AUCs between ROCs (20). We also calculated several measures from the confusion matrix, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. Further, we evaluated the pathophysiological relevance of the models by relating feature importance to the absolute value of the coefficients of the hyperplane that defines the optimized SVM model. To determine if between-site effects had an impact on the machine learning performance, we also conducted secondary machine learning analyses in which we harmonized the dMRI data using the ComBat batch-effect correction tool, as it has recently been shown to be effective in correcting multisite dMRI data (21).

AID-P Application: A Comparison of Imaging, Clinical, and Pathological Diagnosis

We obtained 5 patients (3 from UF; 2 from PSHMC) who had in vivo dMRI collection as well as post-mortem neuropathological examination. The dMRI data for these subjects was inputted into the AID-P (PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism, MSA vs. PSP) to determine group probabilities. These probabilities were used to classify patients and compared to neuropathological diagnosis.

Role of the Funding Source

The funders in this study (National Institutes of Health and Parkinson’s Foundation) had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Machine Learning Inputs

The averages and standard deviations for each machine learning input feature for each group (Control, PD, MSA, PSP) can be found in Supplemental Table III. Although we conducted machine learning on both unharmonized and harmonized dMRI data, the ROC curves were similar (Supplemental Figure 3).

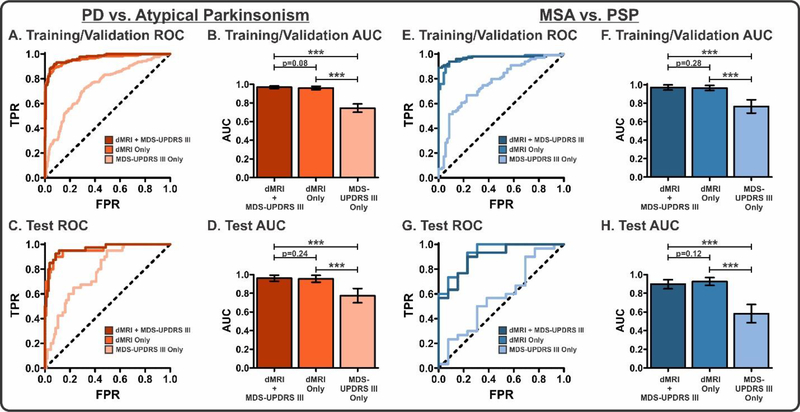

PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism

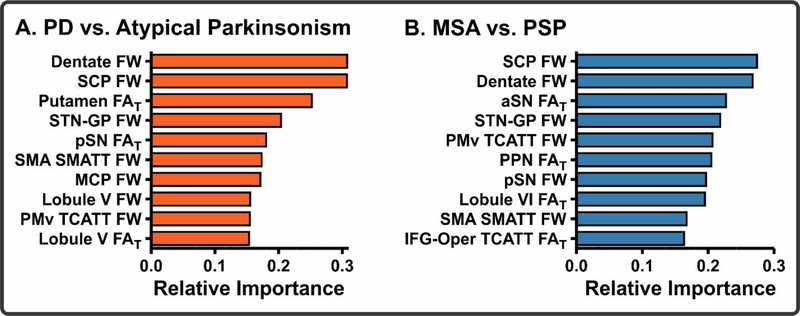

To evaluate the performance of the PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism machine learning models (dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III, dMRI Only, MDS-UPDRS III Only), we conducted ROC analyses in the training/validation (Figure 3A–B) and test cohorts (Figure 3C–D). The dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III model demonstrated high AUCs in both the training/validation (0·969) and test (0·962) cohorts. Similarly, the dMRI Only model showed high AUCs in the training/validation (0·961) and test (0·955) cohorts; however, the MDS-UPDRS III Only model had substantially lower AUCs (training/validation: 0·745; test: 0·775). In both the training/validation and test cohorts, there were significant differences between the dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III and MDS-UPDRS III Only models as well as between the dMRI Only and MDS-UPDRS III Only models (p<0·0001). There was no significant difference between the dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III and dMRI Only models. An analysis of variable contribution in the dMRI Only model revealed that the top 10 contributors to the model included many regions previously shown to pathologically involved in Parkinsonism (22) (Figure 4A). Additional machine learning performance metrics, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value, were calculated (Table II). An important consideration in this comparison is that one contributing cohort (UM) used a lower number of directions than the other cohorts, was the only center which had a b-value of 800 s/mm2, and did not have any MSA/PSP subjects; thus, it is possible that this cohort was skewing results in this analysis. For this reason, we removed this cohort and conducted an identical machine learning analysis. We found that even with the removal of this group we obtained comparable AUCs in the dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III (training/validation: 0·956; test: 0·926) dMRI Only (training/validation: 0·945; test: 0·899), and MDS-UPDRS Only (training/validation: 0·763; test: 0·666) models.

Figure 3. Machine learning performance.

ROC Analyses (A and C) and corresponding AUCs (B and D) for each model in the PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism comparison for the training/validation and test cohorts. ROC Analyses (E and G) and corresponding AUCs (F and H) for each model in the MSA vs. PSP comparison for the training/validation and test cohorts. For each comparison, Delong’s test was conducted to determine between-model differences. ***p<0·0001. Bars represent mean with 95% confidence interval error bars.

Figure 4. Machine learning pathophysiological relevance.

The top 10 predictors of the dMRI Only model for the PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism (A) and MSA vs. PSP (B) comparisons. Abbreviations: SCP, superior cerebellar peduncle; STN-GP, subthalamo-pallidal tract; pSN, posterior substantia nigra; SMA S-MATT, supplemental motor area descending motor tract; MCP, middle cerebellar peduncle; PMv TCATT, ventral premotor cortex transcallosal tract; aSN, anterior substantia nigra; PPN, pedunculopontine nucleus; IFG-Oper TCATT, inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis transcallosal tract.

TABLE II.

Support vector machine learning classification discriminative measures. Training/Validation measures represent the averages with 95% confidence intervals during 5-fold cross-validation. Test measures represent the performance in the test dataset. Sample sizes for each comparison for the Training/Valiation and Test phases of machine learning can be found in Figure 2. Abbreviations: dMRI, diffusion MRI; MDS-UPDRS III, Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; CON, control; PD, Parkinson’s disease; MSA, multiple system atrophy; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy.

| PD vs. Atypical | ||||||

| dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III | dMRI Only | MDS-UPDRS III Only | ||||

| Training/Validation | Test | Training/Validation | Test | Training/Validation | Test | |

| AUC | 0·969 [0·955, 0·982] | 0·962 | 0·961 [0·943, 0·979] | 0·955 | 0·745 [0·701, 0·789] | 0·775 |

| Accuracy (%) | 85·06 [82·57, 87·55] | 91·49 | 85·21 [83·43, 86·98] | 90·24 | 63·00 [59·32, 66·68] | 66·61 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 79·23 [74·16, 84·30] | 92·5 | 78·05 [74·65, 81·45] | 90·00 | 41·53 [32·90, 50·16] | 67·50 |

| Specificity (%) | 90·89 [88·38, 93·40] | 90·48 | 92·37 [89·28, 95·45] | 90·48 | 84·47 [78·46, 90·48] | 65·71 |

| PPV (%) | 89·79 [87·16, 92·14] | 90·67 | 91·29 [88·07, 94·51] | 90·43 | 73·47 [66·24, 80·70] | 66·32 |

| NPV (%) | 81·64 [77·92, 85·36] | 92·35 | 90·91 [88·55, 93·27] | 90·05 | 59·36 [56·13, 62·59] | 66·91 |

| MSA vs. PSP | ||||||

| dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III | dMRI Only | MDS-UPDRS III Only | ||||

| Training/Validation | Test | Training/Validation | Test | Training/Validation | Test | |

| AUC | 0·971 [0·943, 0·998] | 0·897 | 0·965 [0·937, 0·992] | 0·926 | 0·765 [0·693, 0·838] | 0·582 |

| Accuracy (%) | 87·99 [84·23, 91·74] | 80·13 | 84·85 [79·65, 90·05] | 81·79 | 69·97 [62·07, 77·87] | 50·90 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 85·89 [79·50, 92·28] | 83·33 | 83·89 [77·52, 90·26] | 86·67 | 66·79 [57·57, 76·01] | 63·33 |

| Specificity (%) | 90·10 [86·96, 93·24] | 76·92 | 85·81 [80·11, 91·51] | 76·92 | 73·14 [62·24, 84·04] | 38·46 |

| PPV (%) | 89·70 [86·65, 92·75] | 78·31 | 85·64 [80·18, 91·10] | 78·97 | 72·35 [62·10, 82·60] | 50·72 |

| NPV (%) | 86·83 [81·57, 92·09] | 82·19 | 84·41 [78·79, 90·03] | 85·23 | 68·96 [61·15, 76·77] | 51·19 |

Multiple System Atrophy vs. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Identical to the PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism models, the MSA vs. PSP models (Figure 3E–H) had high AUCs in both the dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III (training/validation: 0·971; test: 0·897) and dMRI Only models (training/validation: 0·965; test: 0·926), whereas the MDS-UPDRS III Only exhibited lower AUCs (training/validation: 0·765; test: 0·582). The models were compared using Delong’s test, in which there were significant differences between the dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III and MDS-UPDRS III Only as well as dMRI Only and MDS-UPDRS III Only models (p<0·0001). There were no significant differences between the dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III and dMRI Only models. An analysis of variable contribution in the dMRI model revealed that the top 10 contributors to the model included many regions shown to be pathologically involved in atypical Parkinsonism (22) (Figure 4B). Additional machine learning performance metrics, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value, were calculated (Table II).

Additional Disease-Specific Comparisons

Secondary disease-specific comparisons were also developed, including Control vs. Parkinsonism, MSA vs. PD/PSP, and PSP vs. PD/MSA (Supplemental Figure 2). Performance metrics for these machine learning comparisons can be found in Supplemental Table IV. Further, the Delong’s comparison of model performance (dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III, dMRI Only, MDS-UPDRS III Only) for each disease-specific model can be found in Supplemental Table V.

AID-P Application: A Comparison of Imaging, Clinical, and Pathological Diagnosis

The dMRI data in 5 patients who were followed to post-mortem were used to compare clinical, pathological, and machine learning (i.e., dMRI Only AID-P) ability to predict disease-state (Table III). In 4/5 patients, the clinical, pathological, and AID-P diagnosis matched. In 1 patient, the clinical diagnosis was MSA, but a pathological examination of this individual revealed a PSP diagnosis. The AID-P matched the pathological examination and predicted this patient to have a PSP diagnosis. Thus, the AID-P accurately predicted 5 out of 5 cases at pathology, but more subjects are needed to generalize these findings.

TABLE III.

Application of AID-P to pathological diagnosis in 5 patients.

| Patient | Clinical | Pathological | AID-P: PD vs. Atypical (Group Probability) | AID-P: MSA vs. PSP (Group Probability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | PSP | PSP | Atypical (0·962) | PSP (0·805) |

| B | PSP | PSP | Atypical (1·00) | PSP (0·685) |

| C | PSP | PSP | Atypical (0·955) | PSP (0·947) |

| D | MSA | PSP | Atypical (0·885) | PSP (0·927) |

| E | MSA | MSA | Atypical (0·602) | MSA (0·778) |

DISCUSSION

This study provides a completely automated, objective, validated, and generalizable imaging approach to distinguish different forms of Parkinsonian syndromes using geographically diverse dMRI cohorts. We utilized a large multisite dataset from 17 different MRI scanners aiming to determine if an automated dMRI pipeline with support vector machine learning was capable of differentiating between degenerative Parkinsonian syndromes. Imaging values were extracted from 17 region and 43 tract templates in MNI space. Age, sex, and the MDS-UPDRS III were also collected. All variables were used to develop rigorous disease-specific machine learning comparisons, including PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism and MSA vs. PSP. For each comparison, three models were developed: (1) dMRI + MDS-UPDRS III, (2) dMRI Only, (3) MDS-UPDRS III Only. Their performance was evaluated by creating ROC curves in a test cohort. The dMRI Only models had high accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity for distinguishing between forms of Parkinsonism. The strength of this approach was that it was effective across a range of MRI platforms using standard dMRI sequences, indicating the large impact it could have in clinical trials and clinical care for Parkinsonism.

A difficult problem confronting neurologists in Parkinsonism is the correct classification into idiopathic Parkinson’s disease or atypical Parkinsonism. Misclassification is common, particularly early in the disease (5), which can limit the efficacy of clinical trials that only want to recruit patients with PD. While pathological examination is required for final confirmation of a clinical diagnosis, this cannot be obtained in vivo, when subjects are being recruited and selected for clinical trials. The current study suggests that dMRI, specifically FW imaging, could be used as a marker for detecting structural deficits and is highly accurate in differentiating degenerative Parkinsonisms. Further, our results indicate that dMRI outperformed the MDS-UPDRS III in differentiating Parkinsonian syndromes. Our findings in this large multisite dataset were also capable of distinguishing degenerative Parkinsonian syndromes with high accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

Several prior machine learning studies have been conducted in a variety of neuroimaging modalities, and include structural T1, fluorine-18-labelled-flurodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET, and dMRI (23–26). Further, one study has conducted blood-based neurofilament light (NfL) chain analyses and successfully separated PD from Atypical Parkinsonism with fair accuracy, but this measure was unable to separate MSA and PSP (27). Our automated pipeline (the AID-P) builds upon these studies while incorporating several important and novel features. These include the largest cohort of patients to date, a procedure that is translatable across a large number of scanners using a single pipeline, a completely automated approach, and the inclusion of a distinct test cohort. In the test cohort, we obtained excellent classification of both PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism (AUC: 0·955) and MSA vs. PSP (AUC: 0·926) using only dMRI variables as input. Importantly, the performance in the test dataset was comparable to that of the training/validation dataset, suggesting that our cross-validation approach did not over fit the data and is generalizable to new datasets. Since site was not added as a covariate in the model, the data reported here may generalize to new cohorts on a patient-by-patient basis because the model would not need substantial data from a specific site to produce a predictive value. An important caveat is that the dMRI data collection parameters would need to be consistent with those in Table I, but these scanning parameters are available on most current 3T MRI scanners as a routine sequence.

A potential weakness of this study is that expert clinical diagnosis, not pathologic diagnosis, was used to define subject classifications; however, given that the Parkinsonism subjects had relatively advanced disease severity, misdiagnosis is less probable. Further, three cohorts (UM, PPMI, and 4RTNI) included radiotracer scans confirming that a dopaminergic deficit exists. Future evaluation of this method should involve patients with lower disease severity as well as other diseases which are often misdiagnosed as Parkinsonisms, including dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD)(3). A longitudinal assessment of the AID-P would be particularly useful in determining how well it predicts subsequent pathology in a large cohort. Moreover, the sample size of MSA and PSP patients will need to be larger in future machine learning models, which should further enhance accuracy of the method. The relative ease of obtaining dMRI data will facilitate these kinds of studies. In the interim, if the AID-P is used for subject classification in clinical research, the recommended approach would be to use it in conjunction with expert clinical evaluations.

In each machine learning model, a weight was given to each of the regions or tracts. The regions and tracts with the highest weights contribute the greatest in classifying subjects in the model. It is important to determine how the regions identified by the model may compare with prior neuropathological evidence in the literature. In the PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism model, we found that the most important features in the model included FW in the dentate nucleus, superior cerebellar peduncle, subthalamo-pallidal tract, and FAT in the putamen. In the MSA vs. PSP model, we found that the most important features in the model included FW in the superior cerebellar peduncle, dentate nucleus, and subthalamo-pallidal tract, and FAT in the anterior substantia nigra. These results largely agree with pathological reports in MSA and PSP (28, 29). In MSA, neuropathology is exhibited as glial cytoplasmic inclusions in the nigrostriatal and olivopontocerebellar pathways (29); whereas, neuropathology in PSP is exhibited as neurofibrillary tangles and/or atrophy in regions that include the basal ganglia, frontal cortex, midbrain, and the superior cerebellar peduncle(28). While we didn’t directly evaluate the neuropathological characteristics in all subjects in our cohort, we tested models created from a large dataset of parkinsonism subjects on 5 patients with post-mortem confirmed diagnosis. We found that the AID-P performed with 100% accuracy in these cases (Table III). Furthermore, in one patient, the AID-P agreed with the post-mortem diagnosis while the clinical diagnosis did not. This example illustrates the valuable utility of the AID-P in the clinical setting.

In summary, the AID-P provides an automated, objective, validated, and generalizable imaging approach to distinguishing different forms of Parkinsonian syndromes. Using dMRI datasets obtained from a total of 17 different MRI scanners and geographically diverse cohorts, in conjunction with 60 freely anatomical region/tract templates in MNI space, this study provides strong evidence that dMRI alone can assist in the diagnosis and differentiation of different forms of Parkinsonism. Future work is needed to assess the AID-P from other cohorts across the globe, and the creation of a software platform using cloud computing will facilitate international use of the AID-P. Furthermore, future studies could implement automated quality control steps which would eliminate the need to visually inspect each patient’s dMRI map in MNI space (30). This imaging method does not involve radioactive tracers, and the scan can be collected in less than 12 minutes on 3T scanners worldwide. The outcome of the current study suggests that the AID-P may function well using new data from new sites that have incorporated pulse sequences consistent with the MRI scanners used in this study.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

Parkinson’s disease (PD), multiple system atrophy (MSA), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) are neurodegenerative disorders which are challenging to differentiate in a clinical setting as they often share motor and non-motor symptoms. While dopamine transporter imaging can detect nigrostriatal denervation, it cannot distinguish between different forms of parkinsonism. Prior studies have shown some promise in using diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) to distinguish PD, MSA, and PSP, but these prior studies used small samples and most importantly were only tested at one imaging site. The main challenge in neuroimaging studies is in evaluating a procedure in multisite cohorts. Using dMRI as a method offers unique clinical importance because it can be performed on most 3T scanners world-wide, does not need a contrast drug, and the data can be acquired within a 12 minute scan.

Added value of this study

Here, we created an automated imaging analysis procedure which was tested in 1002 subjects across 17 MRI sites, making this the largest cohort of parkinsonism evaluated to date. The inputted regions were relevant to parkinsonism, and consisted of regions within the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and cortex. Using a fully automated approach, we found that dMRI is capable of differentiating PD from MSA/PSP, and MSA from PSP, with high accuracy across 17 MRI sites. The top regions identified were those previously shown to be pathologically involved in PD, MSA, and PSP. In a subset of 5 cases, the dMRI diagnosis matched pathological diagnosis. This study developed a region of interest template as well as three white matter tractography templates, all of which are available to the public which will expedite future studies in parkinsonism.

Implications of all the available evidence

This study provides an objective, validated, and generalizable imaging approach to distinguish different forms of Parkinsonian syndromes using geographically diverse dMRI cohorts. Our results are relevant in the clinical setting because they indicate that dMRI may provide a biomarker for physicians to use in considering a patient to have atypical parkinsonism or PD, and in distinguishing between MSA from PSP. The outcome of the current study suggests that the imaging and machine learning model may function well using new data from new sites.

Acknowledgments

Funding

National Institutes of Health (U01 NS102038, R01 NS052318) and Parkinson’s Foundation (PF-FBS-1778)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Litvan I, Agid Y, Calne D, Campbell G, Dubois B, Duvoisin RC, et al. Clinical research criteria for the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome): report of the NINDS-SPSP international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litvan I, Goetz CG, Jankovic J, Wenning GK, Booth V, Bartko JJ, et al. What is the accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of multiple system atrophy? A clinicopathologic study. Arch Neurol. 1997;54(8):937–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lees AJ. The accuracy of diagnosis of parkinsonian syndromes in a specialist movement disorder service. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 4):861–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beach TG, Adler CH. Importance of low diagnostic Accuracy for early Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2018;33(10):1551–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adler CH, Beach TG, Hentz JG, Shill HA, Caviness JN, Driver-Dunckley E, et al. Low clinical diagnostic accuracy of early vs advanced Parkinson disease: clinicopathologic study. Neurology. 2014;83(5):406–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jankovic J, Rajput AH, McDermott MP, Perl DP. The evolution of diagnosis in early Parkinson disease. Parkinson Study Group. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(3):369–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(3):181–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlmutter JS, Norris SA. Neuroimaging biomarkers for Parkinson disease: facts and fantasy. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(6):769–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basser PJ, Pierpaoli C. Microstructural and physiological features of tissues elucidated by quantitative-diffusion-tensor MRI. 1996. J Magn Reson. 2011;213(2):560–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Planetta PJ, Ofori E, Pasternak O, Burciu RG, Shukla P, DeSimone JC, et al. Free-water imaging in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 2):495–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, Brooks DJ, Mathias CJ, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008;71(9):670–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goetz CG, Stebbins GT, Tilley BC. Calibration of unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale scores to Movement Disorder Society-unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale scores. Mov Disord. 2012;27(10):1239–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. Neuroimage. 2012;62(2):782–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasternak O, Sochen N, Gur Y, Intrator N, Assaf Y. Free water elimination and mapping from diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(3):717–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein A, Andersson J, Ardekani BA, Ashburner J, Avants B, Chiang MC, et al. Evaluation of 14 nonlinear deformation algorithms applied to human brain MRI registration. Neuroimage. 2009;46(3):786–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Archer DB, Vaillancourt DE, Coombes SA. A Template and Probabilistic Atlas of the Human Sensorimotor Tracts using Diffusion MRI. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28(5):1685–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Baarsen KM, Kleinnijenhuis M, Jbabdi S, Sotiropoulos SN, Grotenhuis JA, van Cappellen van Walsum AM. A probabilistic atlas of the cerebellar white matter. Neuroimage. 2016;124(Pt A):724–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Archer DB, Coombes SA, McFarland NR, DeKosky ST, Vaillancourt DE. Development of a transcallosal tractography template and its application to dementia. Neuroimage. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res. 2011;12:2825–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortin JP, Parker D, Tunc B, Watanabe T, Elliott MA, Ruparel K, et al. Harmonization of multisite diffusion tensor imaging data. Neuroimage. 2017;161:149–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickson DW. Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism: neuropathology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scherfler C, Gobel G, Muller C, Nocker M, Wenning GK, Schocke M, et al. Diagnostic potential of automated subcortical volume segmentation in atypical parkinsonism. Neurology. 2016;86(13):1242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang CC, Poston KL, Eckert T, Feigin A, Frucht S, Gudesblatt M, et al. Differential diagnosis of parkinsonism: a metabolic imaging study using pattern analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(2):149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tripathi M, Tang CC, Feigin A, De Lucia I, Nazem A, Dhawan V, et al. Automated Differential Diagnosis of Early Parkinsonism Using Metabolic Brain Networks: A Validation Study. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(1):60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbagallo G, Sierra-Pena M, Nemmi F, Traon AP, Meissner WG, Rascol O, et al. Multimodal MRI assessment of nigro-striatal pathway in multiple system atrophy and Parkinson disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31(3):325–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansson O, Janelidze S, Hall S, Magdalinou N, Lees AJ, Andreasson U, et al. Blood-based NfL: A biomarker for differential diagnosis of parkinsonian disorder. Neurology. 2017;88(10):930–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickson DW, Rademakers R, Hutton ML. Progressive supranuclear palsy: pathology and genetics. Brain Pathol. 2007;17(1):74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koga S, Aoki N, Uitti RJ, van Gerpen JA, Cheshire WP, Josephs KA, et al. When DLB, PD, and PSP masquerade as MSA: an autopsy study of 134 patients. Neurology. 2015;85(5):404–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bastiani M, Cottaar M, Fitzgibbon SP, Suri S, Alfaro-Almagro F, Sotiropoulos SN, et al. Automated quality control for within and between studies diffusion MRI data using a non-parametric framework for movement and distortion correction. Neuroimage. 2019;184:801–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.