Abstract

Research regarding intimacy within Black relationships is often deficiency-focused, reinforcing negative stereotypes about Black people’s capacity to relate in sexual and romantic relationships. Utilizing social exchange theory and social learning theory as a combined framework, we examined intimacy-related narratives of 18 Black college students during their first and last sexual encounters. A thematic analysis constructed five themes: (a) limited knowledge of intimacy, (b) internal barriers to non-sexual intimacy, (c) external barriers to non-sexual intimacy, (d) seeking an emotional connection, and (e) experiencing intimacy. Findings suggest varying perspectives and experiences related to intimacy. Intimacy barriers and facilitators are discussed.

Keywords: Intimacy, Black individuals, qualitative, sexual experiences, college students

Intimacy related to Black people, individuals of African-descent throughout the Black diaspora, is an under-researched phenomenon. Since Black sexuality has been viewed in contrast to Whiteness (Benard, 2016; Collins, 2004), numerous studies have framed Black relationships and sexuality from a perspective of negativity and deficiency (Sobo, 1993; Williams et al., 2008). The misrepresentations of Black people as unable or unwilling to build intimacy may be used to explain the decline in relationship stability among Black individuals, particularly those considered to be emerging adults (Kogan, Yu, & Brown, 2016). However, it is important to challenge this assumption with inquiry. Previous research has yet to conduct a thorough analysis examining how factors such as attitudes and beliefs, cultural messages, and pressures from larger society impact the ways in which Black individuals experience intimacy in their lives.

Acknowledging these gaps in current psychological literature, this qualitative study examines how Black college students experience intimacy during their first and last sexual encounters. This analysis suggests intimacy is experienced differently depending on participants’ intersecting racial, sexual, and gender identities. Additionally, by offering a balanced view of Black intimacy, this paper adds a strengths-focused perspective to the current body of literature focused on Black relationships and sexuality.

Literature Review

Types of Intimacy

Moss and Schwebel (1993) proposed a working definition of intimacy as “the level of commitment and positive affective, cognitive, and physical closeness one experiences with a partner in a reciprocal (although not necessarily symmetrical) relationship” (p. 33). Within this overarching definition, components of intimacy can be realized in various ways. Emotional intimacy includes exchanging feelings with another person, which is deeply rooted in the value of self-disclosure (Lewis, 1978). Cognitive intimacy includes exchanging thoughts and sharing ideas with another person (Blieszner & De Vries, 2001). Sexual intimacy is being attracted to another person and choosing to share one’s body in the forms of physical contact, affection, and sexual activities (Weinstein & Rosenhaft, 1991). Lastly, although not a part of Moss and Schwebel’s working definition, spiritual intimacy is characterized by shared thoughts and feelings regarding religion, existentialism, and morality (Bagarozzi, 2014), which we believe is culturally salient for many Black people in addition to the other components. For the purposes of this study, the authors define intimacy as a level of closeness with a partner comprised at least one of four aspects: emotional, mental, sexual, and spiritual components. Fostering intimacy requires intention, communication, vulnerability, and familiarity developed over time. We propose combining multiple components of intimacy (e.g., sexual and emotional) can enhance closeness between partners (Laurenceau, Feldman, Barrett, & Rovine, 2005).

Existing literature suggests intimacy is a key factor in relationship sustainment. Intimacy can function similarly to social support as an intrinsic need to buffer loneliness in interpersonal relationships (Hook, Gerstein, Detterich, & Gridley, 2003; Reis & Shaver, 1988). Mehta et al. (2016) asserted greater feelings of intimacy were associated with greater positive affect. In addition, intimacy has been found to have a positive association with overall mental health, specifically with lower rates of depression (Yoo, Bartle-Haring, Day, & Gangamma, 2014). For our college-aged sample, building intimacy in dating and sexual relationships can reduce mental health concerns and promote overall well-being (Braithwaite, Delevi, & Fincham, 2010). Further, from a developmental perspective, intimate experiences during adolescence are linked to identity development and relationship formation, forecasting stability in future relationships such as marriage and parenthood (Beyers & Seiffge-Krenke, 2010).

Although there is an extensive amount of literature related to intimacy and relationship stability (Braithwaite, Delevi, & Fincham, 2010; Mehta et al., 2016; Reis & Shaver, 1988, Yoo, Bartle-Haring, Day, & Gangamma, 2014), there is a dearth of research examining intimacy within Black populations (Awosan & Opara, 2016). Researchers and clinicians have acknowledged several threats to intimacy for Black persons, such as racism and discrimination, negative stereotypes, gender ratio imbalance, poverty, and media and technology (Helm & Carlson, 2013); however, exploring how Black individuals experience intimacy within the context of their sexual encounters can expand our current understanding of intimacy to capture both positive and negative aspects. The processes by which intimacy occurs and what influences intimacy need further exploration.

Intimacy as an Interpersonal Exchange

We integrate two theories to explain how intimacy occurs at a dyadic level: social exchange theory and social learning theory. First, to foster and maintain intimacy, partners have to attend to each other’s needs. Research reveals some partners tend to place a greater emphasis on emotional intimacy whereas other partners view sexual intimacy as more important (Sedikides, Oliver, & Campbell, 1994). In a study examining intimacy among emerging adults, some women prioritized emotional intimacy and some men emphasized sexual intimacy (Shrier & Blood, 2016). These goal-driven behaviors can create imbalance if partners are not willing to communicate and tend to each other’s desires through mutual exchange.

The social exchange framework can be applied to sexuality and relationships from the perspective of negotiating resources to fulfill a need (Sprecher, 1998). Intimacy can be exchanged for sex, love, affirming emotions, time, money and gifts (Lewis, 1978; Sprecher, 1998). Viewing intimacy as a transactional process suggests that the relationship consists of an input of investments, output of rewards, and reciprocity. If one individual is investing more intimacy than the other party, then benefits may not be reciprocal. Additionally, if the type of investment differs, parties may perceive unequal benefits without communication and understanding. Based upon stereotypical gender differences in relationship motives, the experience of intimacy can vary. For example, women may pursue relationships for the benefits of emotional communication and self-growth. Men, on the other hand, may view sexual gratification as a benefit to relationships (Sedikides, Oliver, & Campbell, 1994). However, this research offers a narrow, stereotypical view on the exchange of intimacy between men and women, without accounting for external influences such as patriarchy, culture, and race that complicate the process (Randolph, 2018). The painting of men with no desire for emotional intimacy and women without a desire for sexual intimacy should be challenged, as it perpetuates an unfinished story of men and women’s wants and needs from each other.

Intimacy as a Learned Behavior

Intimacy can also be understood through the lens of social learning theory, which posits we learn through observing others (Bandura, 1977). Behavior both influences and is influenced by our personal characteristics and social worlds, coined as triadic reciprocal determinism (Bandura, 1978). Our understanding of intimacy is heavily influenced by factors of our social environment such as family and peers, cultural norms, and media sources, and personal factors, such as attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding intimacy and behaviors exemplified through relationship scripts. An accumulation of the aforementioned factors impact how Black individuals learn, model, and experience intimacy in their relationships.

Family systems.

Emerging adults are strongly influenced by the relationship between their parents (Allen & Mitchell, 2015). Family members communicate their emotional processes, attitudes, values, and beliefs over generations (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). A study by Grange, Brubaker, and Corneille (2011) exploring family messages demonstrated Black emerging adult women receive most sexual socialization from older female family members, but also from male family members, which informed their views on sex and relationships. Older women emphasized receiving economic support from men, whereas same-aged women discussed the importance of emotional intimacy with male partners. What’s more, messages from male family members warned Black women about men’s relationship behaviors focused on sex and mistreatment, with limited insight into what should be expected of male partners. In general, Black women encounter messages about sex and relationships that seemingly contradict.

Compared to their female counterparts, literature regarding Black men’s sex and relationship socialization is scarce. However, it is hypothesized Black men’s experiences with their family of origin directly correlate to their attitudes and beliefs about relationships as well (Perry, 2013). Experiences of harsh and emotionally unsupportive parenting during mid-adolescence has been shown to affect relationship behaviors later in emerging adulthood (Kogan, Yu, & Brown, 2016). Additionally, Black men have highlighted seeing their fathers engage in promiscuous behaviors influenced their regard and respect for women and served as a model for them to also engage in sexually promiscuous behaviors (Willis & Clark, 2009). However, men whose families provided examples of healthy relationships were guided with rules and expectations about how to respect their partners and relationships (Perry, 2013).

A study by Kane (2000) exploring Black family dynamics demonstrated participants experienced their families as warm and expressive but less trusting in nature. Consequently, research on gender relations between Black men and women also indicates a sense of mistrust between the two groups, serving as a barrier to experiencing emotional intimacy (Franklin, 2001). There are limited examples of positive Black healthy and functional relationships, as many individuals do not grow up with these models in their households (Western & Wildeman, 2009). Therefore, some Black men and women may have been socialized to be distrustful of each other in relationships due to family and cultural messages (Awosan & Opara, 2016), which can prevent the development and ability to sustain intimacy, whereas others who have had intimacy modeled are better able to articulate and meet intimacy needs.

Relationship scripts.

Research has highlighted a discrepancy in how Black men and women internalize relationship scripts, and thus how such scripts inform their desires for intimacy (Bowleg, Lucas, and Tschann, 2004; Lima, Davis, Hilyard, Jeffries, & Muilenburg, 2018; McLellan-Lemal et al., 2013). Utley (2010) argues intimacy between Black couples has been dominated by an overconsumption of Black sexual content. Gender and sex roles influence the discussion of intimacy during sexual experiences. Bowleg, Lucas, and Tschann (2004) indicate Black women in their study had three intimate relationship scripts: 1) men control relationships, 2) women are responsible for maintaining relationships and 3) infidelity is normal, and two sexual scripts: 1) men control sex and 2) women desire condom use, but men control condom use. Scripts related to control speak to the potential imbalance in social exchange, as it relates to various components of intimacy; however, these scripts only represent Black women’s perspective in research.

McLellan-Lemal et al. (2013) conducted a qualitative study where Black women detailed how their romantic desires as well as life circumstances posed relationship challenges which hindered intimacy building. Although Black women in this study wanted more intimate and monogamous relationships, they reported difficulties combating social norms that promote non-monogamy. As suggested by this study, some Black women have learned to integrate the possibility of infidelity and abusive relationship behaviors into their relational scripts. Thus, in order to fulfill some level of intimacy, women may use sex as a function of currency in exchange for emotional intimacy from their partners.

Similarly, research on Black men’s relationships scripts is conflictual, such that men experience competing desires for emotional and sexual intimacy in their dating and first sexual encounters with women (Seal & Ehrhardt, 2003). The sexual pursuit and conquest of women tends to represent both heterosexuality and masculinity for men in emerging adulthood (Randolph, 2018). However, men also view emotional intimacy as a primary goal, and having sex as a secondary goal, of their dating behaviors (Seal & Ehrhardt, 2003). For some, if sex occurs too early, it can be an impediment to developing emotional intimacy (Seal & Ehrhardt, 2003). Some men also described emotionally intimate relationships as scary and sexually limiting. Therefore, seeking sexual intimacy with a casual partner and emotional intimacy with non-sexual partners may be a manifestation of internalized conflictual messages about masculinity and male gender roles (Charleston, 2014; Seal & Ehrhardt, 2003).

Media influences.

A study found 80% of its sample of college students believe media influences their relationships, even more so than parental influences (Trotter, 2010). As emerging adults experience many transitions (e.g. graduating high school, completing college, changing jobs, moving) at this stage in their lives, media has a strong influence on how they explore, construct, and express their identity (Coyne & Padilla-Walker, 2013). Unfortunately, anti-black narratives, stereotypes and messages transmitted through media also have a profound impact on the ways in which Black individuals perceive and interact with each other (Kelly & Floyd, 2001). Despite initiatives to display Black relationships in a positive light with shows like The Cosby Show and Blackish (Stamps, 2017), Stephens (2012) asserts hip-hop culture has influenced the quality and stability of Black relationships through negative images and stereotypes. Moreover, hip-hop encourages emotional closeness and intimacy between men at the expense of relationships with women (Randolph, 2018). Hence, music further perpetuates barriers between the two genders through the lens of sexual objectification and stereotypes (Cole & Guy, 2009).

Considering the context, media depicts Blacks as hypersexual beings without allowing them opportunity to define, enjoy, or appreciate intimacy (Bowleg et al., 2011). As such, there are few portrayals of Black partners in movies or TV shows that focus on emotional, spiritual, or mental intimacy (Johnson & Loscocco, 2015). Based on our definition of intimacy, the media primarily depicts Black partners to engage solely in sex and sexual intimacy. However, having non-committal sex does not mean a person is incapable of experiencing the other three components of intimacy identified above.

As evidenced by our literature review, Black relationships are presented through a deficit-focused perspective, whereby Black individuals are not seen as capable of having the necessary tools to foster intimacy. Conflicting familial and cultural messages, media and technology, and societal gender norms prevent access to such tools (Awosan & Opara, 2016; Kelly & Floyd, 2001; Lima, Davis, Hilyard, Jeffries, & Muilenburg, 2018; Western & Wildeman, 2009). Further, for Black emerging adults, experiences of noncommittal relationships may be characteristic of their developmental processes. However, this fact does not negate the need for various types of intimacy in their romantic lives. Littlejohn-Blake and Darling (1993) argue Black men and women need to increase their understanding of intimacy to learn how to have positively impactful relationships. Additionally, Awosan & Hardy (2017) asserts more research is needed to explore attitudes, beliefs, and emotional processes that impede development of intimacy among Black men and women. The premise of these calls to action is that Black people do not already have the capacity to relate intimately. Therefore, this analysis seeks to fill this gap in literature and present a more comprehensive view of Black intimacy among college students.

The Current Study

The current study explores the experiences of intimacy for Black college students within the context of their sexual encounters. The research question was, “what are the experiences of intimacy during sexual encounters of Black college students?” First, we reviewed relevant literature regarding the construct of intimacy and the facilitators and barriers of intimacy in relationships. Next, we combined social exchange and social learning theories (Bandura, 1978; Sprecher, 1998) to provide a framework for viewing intimacy as an interpersonal exchange process situated in the context of social learning from external stimuli. This combined framework allowed us to examine the factors that influence participants’ learning about intimacy, as well as to explore how participants negotiate exchange of intimacy in their sexual encounters. After describing the methods of this study, we detail the findings from this study and discuss them with the understanding of an established, positive association between emotional intimacy and sexual intimacy (Yoo, Bartle-Haring, Day, & Gangamma, 2014). Finally, we offer limitations of our study and directions for future research on Black intimacy.

Methods

Sample Description

The sample for this study included eighteen Black college students (nine males and nine females). Participants were recruited from a large public university located in the southeastern United States through the use of flyers, online posts via message boards and listservs, and snowball sampling. To participate in this study, participants had to self-identify as Black, be at least eighteen years old, and be willing to discuss their sexual encounters. After being screened for eligibility, participants were interviewed using a semi-structured protocol about their first and last sexual encounters. All participants identified as Black; however, three participants also identified as biracial and two identified as having African descent from Nigeria and Zimbabwe. Regarding sexual identities, two participants self-identified as a part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) identity-one as gay and the other as pansexual. Pansexuality refers to a romantic, emotional, and sexual attraction to people of all genders (Rice, 2015). The participant who identified as pansexual stated she “can fall in love with anybody” regardless of a person’s gender or sexual identity. In the interviews, the gay-identified participant reported a same-sex partner in his first and last sexual encounter. The remaining participants identified as heterosexual, with two straight-identified participants disclosing same-sex attraction or experiences.

Data Collection Procedures

Participants completed the study interview in a secure, private office, after reviewing and accepting the informed consent. Participants were informed during the consent process that they could skip any interview questions they did not want to answer. Relevant to the current paper, participants were asked about their first-and last-time sexual encounters and how they would describe the experiences based on intimacy. Additionally, participants were asked about the interview experience as it related to race, gender, and sexual identity similarities and differences. For example, interviewers asked, “What is it like talking to me about this?” and “Is there anything that I didn’t ask that you think I should know?” It was not overlooked that participants’ race, gender, and sexual identities would influence the interviewing process. Therefore, interviewers offered space for participants to discuss any concerns that were salient to their identity without asking leading questions. All participants answered all of the interview questions posed. The interviews lasted an hour on average and were audio-recorded and transcribed by the research team. This study was IRB approved.

Data Analysis

This study employed thematic analysis of existing data (Terry, Hatfield, Clarke & Braun, 2017). Transcripts were coded by a team, where all members familiarized themselves with the data, initially coded transcripts line-by-line, and then verbally processed their findings with other teammates (Berends & Johnston, 2005; Nowell, Norris, White & Moules, 2017). Research members were also required to keep memos of their reactions and questions while reading and analyzing the data (Birks, Chapman, & Francis, 2008). During the coding process, research members were first asked to read the transcript without note-taking. Then members were required to read each transcript again and conduct line-by-line coding using descriptive gerunds. When generating codes, researchers could also list semantic or latent codes (Terry, Hatfield, Clarke & Braun, 2017). Semantic codes are descriptive and seek to summarize the content of the data, whereas latent codes are based upon interpretations by researchers. Typically, the researchers asked follow-up questions about what was said to explore underlying messages which may have not been verbally articulated during the individual interviews. Lastly, it was requested that research members read transcripts for a third time for patterns or underlying themes as participants shared their stores.

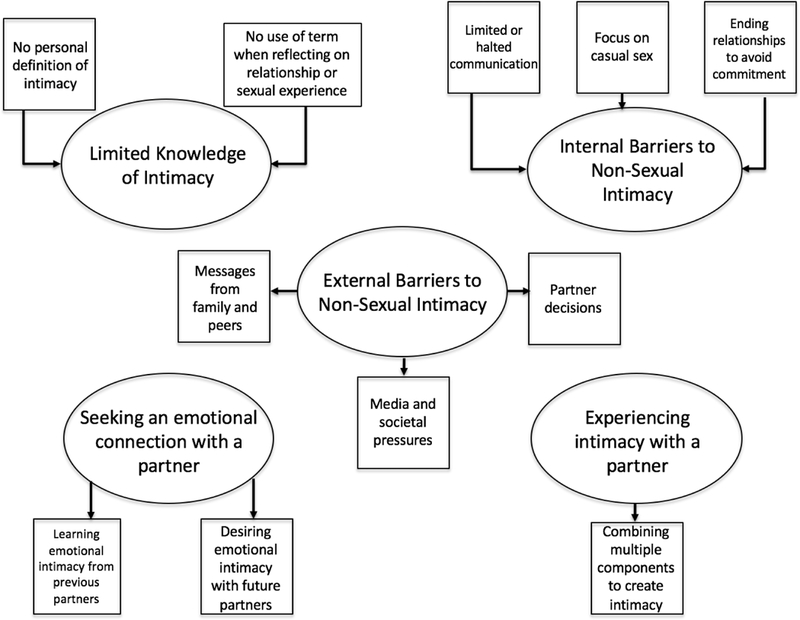

Following the three stages of coding, the first author developed preliminary themes for team members to review. In subsequent team meetings, members were asked to re-read their transcripts, review their codes, and write down the codes that would align with the assigned theme. Each team member reviewed each code to determine best fit under the preliminary themes. Categories of codes were reviewed to consider if additional categories were overlooked and needed to be added. Thus, overlapping codes were condensed into one category. Lastly, each team member read their assigned transcripts once more to select quotes that best represented each theme, using their codes as a reference point. Through group consensus, final quotations and themes were selected to be published in the paper. A thematic map was created to illustrate themes from the data (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Thematic Map

Researcher Subjectivities

The research team consisted of a diverse group of students and their faculty advisor. Interviewers from the larger parent study (Hargons et al., 2018) included seven team members – two Black females (including the faculty advisor), four White females, and one White male. Four of the interviewers identified as straight, two as queer, and one as polyamorous. All research members were trained on Black sexuality and qualitative research methods by the faculty advisor.

The research team who reanalyzed the data and are authors of this paper included three Black females (including the faculty advisor), two Black males, and one White female, all enrolled in a counseling psychology program. Five team members identified as heterosexual and one identified as queer. Given the interest in research regarding relationship experiences of Black individuals such as love and intimacy, the research team was invited to collaborate on this study with the first author.

The researchers of this paper sought to understand experiences of Black intimacy, as it is a topic not widely represented in extant research. Since all research team members are in the faculty advisor’s research lab on sexuality, conversations related to sexual pleasure, relationships, and identity intersectionality occurred throughout the data re-analysis and manuscript writing process. Specifically, every week, research members discussed their definitions of intimacy, relationship experiences, and thoughts and feelings about the current status of Black relationships. These conversations were important to facilitate consciousness of how our own lived experiences and biases could influence the re-analysis and interpretations of participants’ narratives.

Results

Through secondary data analysis, this study sought to explore experiences of intimacy in the context of first and last sexual encounters of Black college students. Five themes were found to be salient in the data: 1) limited knowledge of intimacy, 2) internal barriers to non-sexual intimacy, 3) external barriers to non-sexual intimacy, 4) seeking an emotional connection with a partner, and 5) experiencing intimacy with a partner. Themes are depicted in a visual map (see Figure 1) to represent the different components of intimacy and the knowledge and experiences of intimacy during sexual encounters.

Theme One: Limited Knowledge of Intimacy

Some participants struggled to offer their definition of intimacy; they may also have reflected on an experience or relationship without using the specific term. This could have been due to a limited understanding of intimacy. A few participants requested clarification when invited to discuss any intimacy they experienced. For instance, Binda responded by asking the interviewer, “What do you mean by intimate? Cause people think about it in different ways. What do you think intimate is?” Additionally, in referencing his first sexual encounter, Devin acknowledged that he had a limited understanding of intimacy by stating: “I didn’t understand the role of intimacy in sex cause like I never saw it in the porn I was watching, so the whole role of intimacy was definitely not there the first couple of times.”

Other participants described their experiences of emotional or mental intimacy without necessarily labeling the experience as intimate. For example, Kevin explained his knowledge of intimacy by comparing his first and last sexual experiences. He shared, “I feel like it’s [sex] either meant for like fun or like loving. Like there’s two different types of sex…like the loving, the meaningful, passionate sex and the other one where you just like to do it to fulfill your needs and stuff like that.” In summary, limited knowledge about intimacy often constrained the way participants discussed it in the interview, even when they noted awareness of the construct and components of intimacy. Almost exclusively, components of emotional and sexual intimacy, rather than mental and spiritual intimacy, were discussed.

Theme Two: Internal Barriers to Non-Sexual Intimacy

Participants described a number of barriers that kept them from fully experiencing intimacy in their first and most recent sexual encounters. The barriers participants described were both internal and external. These barriers have been divided into two themes, because internal and external barriers served different purposes and led to different experiences for participants.

The second theme focused on participants’ experiences of internal, or self-imposed, barriers to their intimacy. Participants described taking active steps to decrease their experience of non-sexual intimacy or avoid non-sexual intimacy altogether within their relationships. These barriers were sometimes put into place out of fear or mistrust, and therefore served a protective role. Common self-imposed barriers included halting or limited communication, ending relationships prematurely to avoid commitment, and emphasizing casual sex over non-sexual intimacy. Olivia noted, “a boy can pour their heart to me, but I really won’t care because I have brothers. I see what they do. I’m really knowledgeable of the game,” highlighting how she learned from her brothers to view men suspiciously in relationships. For Olivia, avoidance of non-sexual intimacy sought to protect her from getting hurt as men engage in “the game.”

Some participants emphasized creating self-imposed barriers from their desire to keep their partners from getting hurt. As Devin emphasized, “I’m still having issues trying to either be explicitly clear about all the things I want and not and having them not catch as many feelings.” Some participants emphasized sexual aspects of the relationship and worried about partners “catching feelings,” or developing the desire for emotional intimacy.

Many of the participants interviewed did not express a desire to be in a long-lasting romantic relationship. They were comfortable keeping sex casual and focused on sexual intimacy. As Que explained:

Yeah, I think if you sleep over after you have a thing [sex], you’re attached or something like that…I explained and talked to her about it the next day about feelings and stuff, because I don’t like anybody getting the wrong idea. I’m not that type of person to play with someone’s emotions. That’s messed up.

For Que, his concerns about hurting his partner emotionally were expressed along with a desire to keep things focused on physical intimacy. For him, making sure his partner did not spend the night was a self-imposed barrier that helped him to prevent himself, and hopefully his partner, from sharing emotional intimacy. Spending the night, for Que, may indicate his partner may request more commitment than having casual, non-committal sex. Later in his interview, Que articulated if his sexual partner would like to engage in sexual activity only, then he could resume a relationship with her; however, if she wanted a relationship that required an emotionally intimate connection, going beyond what he is willing to give, he would not continue their sexual relationship.

Theme Three: External Barriers to Non-Sexual Intimacy

Whereas many participants explained ways they actively distanced themselves from experiences of non-sexual intimacy, other participants described external factors that kept them from non-sexual intimate experiences. External barriers to intimacy often came in the form of participants’ partners not wanting an emotionally intimate connection while the participant did. This dynamic led to experiences of unfulfilling intimacy and relationships where participants were settling for the sexual intimacy present in the relationships, even though it might not be the ideal degree or type of intimacy they desired.

For example, Ralph recalled a situation where his partner left him, saying, “That night I told him that I liked him, and that I was getting comfortable with him and that I hoped to see him again. And what do men do when you tell them that? They disappear.” Similarly, Isabelle suggested she and her ex-partner never discussed emotional intimacy when she stated, “We never really had a serious talk about feelings. Ever. If I brought something up, he would brush it off.” In both of these situations, Ralph and Isabelle wanted more emotional intimacy with their partners but were ultimately unfulfilled in this desire, due to lack of communication about their emotional needs.

Binda described her relationship with her unborn child’s father. Their commitment had ended, but she became pregnant after post-relationship sex. She described how he had given her mixed messages about whether or not he wanted a relationship with her, both before and after she learned she was pregnant. Binda described her conflicted feelings towards the relationship:

…I still love him even though he did what he did, but I don’t know why I still do…It’s not hard because (tearful) I guess cause I’m still in love. But I wanna break it off, but it’s like why do that because it’s just gonna be harder on me, honestly not for him.

Although she noted the feelings of love she holds towards her partner, Binda realized she did not experience the same investment of emotional intimacy from him. Because of this disconnect in the types of intimacy between partners, Binda grappled with the conflict between her unrequited feelings of love for her partner, while maintaining some form of relationship with him as she is pregnant with their child.

Other external barriers to non-sexual intimacy often revolved around messages participants received from others. For example, some individuals had been socialized by peers, family, and the media to believe their intimacy input would not equal the desired intimacy output, making the investment seemingly worthless. For example, Jack explained:

My parents would tell me it’s not worth it to have sex just because you could have babies, STDs, and stuff like that, so they were just like you should wait until you find somebody that you know you’re going to be with, potentially be married to you know…I respected it, but it was like man, all these other sources were like “just have sex”. Friends, you know. I grew up when Facebook and everything else was going on, all the pictures, videos, and stuff like that…social media is hypersexual. Some of it’s not even suggestive, it’s just like explicit. Music is always talking about sex and stuff like that. So, there’s really no escaping it. It just makes you want to do it (laughs).

In his interview, Jack underscored conflicting messages he received between his family and other influences, such as social media and music. Conflicting messages presented a barrier to non-sexual intimacy, because of the overemphasis on sexual intimacy.

Theme Four: Seeking an Emotional Connection with Partner

Despite internal and external barriers, some participants still sought emotional and mental intimacy. Devin indicated, “I have yet to have sex with someone I am in love with, so I’m still looking for that.” Further, Jack discussed how he desired emotional intimacy with his ex-partner. He shared,

Me and her, our emotional intimacy is kinda like crazy just because like I’m a big talker, and she’s the opposite. She’s not a big talker. You can get her to talk but you have to get her to talk. So it’s like another job almost. So, our intimacy is like we can be around each other, but we won’t really be like doing stuff together besides sex. Part of the reason why we broke up.

Lastly, Aaliyah stated she is seeking emotional intimacy with future partners by stating:

Once sex comes into the picture, it changes the dynamics of everything. Well, especially if there’s an emotional connection. I think you can have sex with somebody and couldn’t care less about them… But, I think emotional connection is important to have and maintain.

Contrary to messages about casual sex with “no strings attached,” some participants, expressed desire to cultivate emotional and mental intimacy with their sexual partners.

Theme Five: Experiencing Intimacy

Many participants narrated a meaningful experience of closeness and reciprocal care with their sexual partners, which often involved emotional and physical connection, resulting in combined emotional and sexual intimacy. For instance, Devin expressed his enjoyment of deeper sexual intimacy in his first sexual encounter. He described the experience as, “a lot more intimate. Um, I actually felt her vagina. Uh, a lot more kissing. Our bodies were a whole lot closer.” In addition, Harry focused on the sexual and emotional intimacy he experiences in his current relationship. He shared,

I feel the need to embrace her more, and I like to look in her eyes and stuff like that. I like to watch her face and the expressions she makes… it’s just a much more intimate experience cuz, like there was none of that my first time, so it just means more for me now.

Harry was socialized by his grandparents to have sex with a “special” person with whom he had an emotional connection. This participant was able to voice his desire to develop a deeper connection with her both physically and emotionally.

Other participants recalled experiences where they felt connected to their partners. For example, Lorna reminisced about an sexually and emotionally intimate experience she shared with a woman, “I do believe that it [sex] was good – like once again that intimacy and it was just, it was good to be around somebody else. She understood me. I understood her.” Eve also noted emotional exchange between her and a previous partner when she shared:

“He’s my type and because there’s so much love, it wasn’t just a quickie. It was intimate, and we cuddled, and we watched movies, and I fell asleep on his chest, and it was good.”

Lastly, Ralph summarized his thoughts about experiences of non-sexual intimacy after a sexual encounter:

How good the experience of sex is like more so…what happens after sex, rather than during. Because you could have had amazing sex, but then after if you just rolled over on your phone, you’re gonna think about that rather than the sex. My first experience, the sex itself wasn’t good, but because after he was dope to chill with, I would still say it was a good experience, even if it was bad sex.”

Ralph was able to experience emotional intimacy despite having unsatisfying sex. The emotional and mental intimacy made the sexual encounter worth it to him.

Discussion

The present study uniquely contributes to literature regarding Black individuals and their experiences of intimacy in sexual relationships. A combination of social exchange theory and social learning theory contributed to a framework of intimacy, featuring emotional, and physical components, in this study. Thematic analysis identified and examined recurring patterns of intimacy among participants (Terry, Hatfield, Clarke, & Braun, 2017). These themes seek to explain the developing processes of intimacy building, from having a limited self-awareness and understanding of the various components of intimacy to fully experiencing emotional intimacy with a sexual partner.

Some participants exhibited difficulty voicing what intimacy means for them without using the specific term. Sexual stereotypes of prowess and promiscuity have been imposed on Black individuals (Bowleg et al., 2011), limiting their ability to explore their sexual needs and wants in a healthy way. Additionally, research supports the idea of slavery and colonization as significant elements in the lack of emotionality and vulnerability, often used to establish and maintain intimate bonds, between Black persons (Lawrence-Webb, Littlefield, & Okundaye, 2004). Thus, through a generational lens, we hypothesize that language surrounding intimacy, emotions, and sexual satisfaction may have been absent in the socialization of some Black individuals. This fact impacts intimate relationships of Black people who may seek connection but are unable to articulate or express such needs. Randolph (2018) posits Black individuals can collectively challenge existing relationship scripts by offering spaces where individuals, specifically men, can be vulnerable expressing their romantic feelings towards a partner. An avenue to do this work is through hip-hop music, which has historically embodied Black male-female relationship dysfunction (Randolph, 2018).

Unachieved emotional intimacy expectations, from internal and external barriers, stifled the experiences of participants who sought more from the relationship than mere sexual intimacy. Participants’ emotionally distancing behaviors from partners may align with previously mentioned internalized relationship scripts. (Bowleg, Lucas, & Tschann, 2004). Further, the culturally-specific messages Black men and women are taught through their social environments contribute to the expectations they deem as appropriate and acceptable regarding intimacy. If Black individuals have learned they should have sexual prowess and be dominant in the bedroom, then this may leave little room for supporting the emotional, mental, or spiritual needs of a sexual partner for intimacy, causing them to distance themselves from these responsibilities (Bowleg et al., 2011). It may also be the case that some participants did not share mutual emotional connection with their partners, but still wanted to continue a sexual relationship as a way to meet their own needs. Therefore, emotional intimacy requires a negotiation of benefits and costs between partners as mentioned in social exchange theory.

Cultivating any type of intimacy requires partners to agree on what to exchange with each other (e.g., sex, money, emotional support, trust, and communication) (Laurenceau & Kleinman, 2006). In his interview, Que discloses how he communicated the terms he wanted from his partner. Whereas his partner would like more investment from him, Que only expects a sexual connection. To Que, he may view the different aspects of intimacy as isolated, seeking only sexual intimacy in exchange for sexual intimacy with his partner and separating sexual intimacy from other forms. On the contrary, his partner may view emotional intimacy more holistically, seeking an emotional investment from him in addition to sex. Therefore, she may view the exchange as unequal due to her wanting more than sexual intimacy. Recent literature underscores individuals who have a greater desire for casual sex are more likely to perceive a similar sexual intent in their partners (Lenton, Bryan, Hassle, & Fischer, 2007), which is reflected in Que’s interview.

There is a requirement to find a balance between the ideals and the realities of intimacy. As we notice with Binda, some participants sacrificed their desires for non-sexual intimacy and settled for whatever investment they could receive from their sexual partners as a way to partially meet their non-sexual needs. Participants protected themselves by maintaining a false sense of hope that a sexual relationship would result in a more emotionally or mentally intimate connection. Since some Black women may believe their sexual partners control relationships and sex (Bowleg et al., 2004), they may barter sex for emotional intimacy. Contrarily, some Black tend to avoid emotional intimacy by having sex with casual partners with whom they may or may not express their emotional needs. Moreover, men in the emerging adulthood stage may seek casual dating experiences and sexual gratification instead of emotionally intimate relationships with women (Seal & Ehrhardt, 2003). These results presented both confirmatory and contradicting narratives related to these gendered scripts. However, if just one partner is unwilling to make a similar emotional investment, then emotional intimacy will undeniably become harder to foster, regardless of the person’s gender.

A lack of emotional intimacy in relationships may allude to the absence of healthy and sustainable relationship behaviors. Some participants emphasized sexual intimacy with internal barriers to non-sexual intimacy during their interviews. They avoided emotional risk-taking during casual sex, which is a requirement for emotional intimacy building (Reis & Shaver, 1988). Cultural shifts have provided a gateway for casual hookups to occur (Garcia, Reiber, Massey, & Merriweather, 2012). For some, casual sex can be intimate; a person does not have to be in a committed relationship to experience sexual intimacy. Although there may be a desire for a romantic relationship with many of the participants, people interested in casual sex may still engage in affectionate behaviors such as cuddling, foreplay, and spending the night after sex (Garcia, Gesselman, Massey, Seibold-Simpson, & Merriweather, 2018). Usual parameters of monogamy suggest all intimate needs, regardless of type, must be fulfilled by a sole partner. It may also be assumed vulnerability and self-disclosure can only occur with one partner. However, one relationship may not meet all of a person’s intimacy needs and expectations (Schaefer & Olson, 1981). A person’s needs could be fulfilled by multiple relationships. In this case, intimacy exchange would involve more than one other partner.

Though hookups require a mutual exchange of uncommitted sex, they may function as a way to achieve emotional intimacy without formally recognizing and committing to a relationship (Garcia, Reiber, Massey, & Merriweather, 2012). Eventually, parties have to acknowledge the non-sexual intimacy needs of their partner, and then come to an agreement as to whether to continue sexual encounters without emotional intimacy or end the sexual relationship as several participants such as Jack, Que, Aaliyah and Ralph did. Even if Black individuals have no intentions to form a committed relationship, there are several benefits to physical and mental wellbeing that emerge through emotional intimacy and effective communication (Yoo, Bartle-Haring, Day, & Gangamma, 2014).

While some participants were not interested in emotional intimacy with their sexual partner, others actively sought experiences where they were able to foster emotional and mental intimacy. Participants like Ralph and Harry wanted this type of intimacy to be modeled in future sexual encounters. Participants looked for emotional responsiveness from partners and reliability in their sexual partners’ intentions and behaviors as ways to build emotional intimacy. According to social learning theory, participants observed the benefits of emotional intimacy from previous partners. Further, social exchange theory supports that participants seeking an emotional connection were also searching for partners whom were willing to reciprocate the investment (Sprecher, 1998). Participants did not discuss spiritual intimacy to the same degree as sexual, emotional, and mental intimacy. We hypothesize spiritual intimacy was overlooked because it is often linked to marriage (Holland, Lee, Marshak, & Martin, 2016), which did not seem to be a current goal of participants. This finding aligns with Moss and Schwebel’s (1993) early definition of intimacy, which contains only mental, emotional, and sexual components.

Duncombe and Marsden (1993) argue women tend to do more “emotion work” in their relationships compared to men, who focus more on developing sexual intimacy (p. 234). As mentioned earlier, Black men are socialized through multiple avenues to be emotionally detached in order to appear cool (Hooks, 2004). Other literature has offered an alternative explanation: trauma stifles one’s ability to express emotions during sexual encounters and in their interpersonal relationships (Goff et al., 2006). In general, Black men have been viewed as emotionally unavailable and unwilling to foster a connection with a partner (Abrams, Maxwell, & Belgrave, 2018); however, our study findings reveal otherwise. Some male participants did not refrain from expressing their desires for emotional intimacy with a sexual partner. Furthermore, most female participants were able to articulate their own sense of agency regarding sexual intimacy and relationship needs.

Contrary to social messages and media portrayals, Black individuals can experience fulfilling intimate experiences in their sexual encounters, whether they are in a romantic relationship or not. When participants experienced emotional and sexual intimacy with their partners, this led to them being able to provide their own understanding and definition of intimacy, which included an additive effect of an emotional connection to their sexual experience. Our findings suggest as emotional intimacy increased, sex represented more than a physical act for our participants through sensuality, pleasure, and fulfillment (Seal and Ehrhardt, 2003). Overall, these findings demonstrate Black intimacy is more complex than extant research has depicted it. Rose (2003) asserts we can reframe dehumanizing stories about Black people and their intimacy, sexuality, and relationships by providing an opportunity to retell their own stories orally and in research. This study presents a new way of narrating experiences of intimacy for Black individuals that are different from the typical messages broadcasted about Black sexuality and relationships.

Limitations

There are a few limitations in this study that warrant mentioning. Although secondary data analysis has been found to be a valid approach in re-analyzing qualitative data (Irwin, 2013), participants were not specifically asked about their definitions of intimacy. Since the interview questions related to intimacy were confined to participants’ first and last sexual encounters, the understanding and experiences of intimacy presented in this paper may be limited in scope. However, we believe we were able to answer our research question using data from a specific question in the interview protocol. Second, the participants in this study were college students in emerging adult developmental stages. Therefore, we recognize the types of intimacy could look differently for Black adults of varying ages and socioeconomic class. Lastly, the majority of our participants experienced heterosexual encounters. Our paper focuses primarily on male-female interactions, along with the barriers and facilitators to promoting intimacy between these groups. The experiences of sexual and emotional intimacy could potentially look different for same-gender-loving and polyamorous relationships. Black same-gender-loving people may experience barriers posed (e.g., sexual identity discrimination) on their relationships that influence their experience of intimacy differently compared to heterosexual couples. Polyamorous relationships may incorporate exchanging aspects of sexual, emotional, and mental intimacy with multiple partners instead of one partner. Future research should include a more diverse sample of Black participants, including those who represent older ages, different socioeconomic classes, gender expressions, and sexual identities.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to describe experiences of intimacy, or a lack thereof, in the lives of Black individuals through the combined frameworks of social exchange and social learning theories. Additionally, this paper sought to illuminate such narratives with a more holistic lens of factors influencing these experiences. In support of extant research, our findings demonstrate the idea of sexual exploration and relationship instability as somewhat typical in the emerging adult developmental stage. However, this paper distinguishes itself from existing literature that contributes to Black individuals’ sexuality and relationships from a deficit, hypersexual perspective (Sobo, 1993; Williams et al., 2008). Our results highlight Black emerging adults also desire emotional and sexual intimacy in their casual sexual encounters, and both committed and non-committed relationships. On a micro level, the willingness to place an investment of vulnerability, emotions, and communication in a relationship through reciprocation facilitates intimacy. Moreover, on a macro level, the capability to counter messages from larger society about Black sexuality and relationships contribute to intimacy-related experiences for this population.

Author Acknowledgments:

We appreciate the participants who shared their stories with us. Declarations of Interest: This research was supported by the University of Kentucky and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) [T32-DA035200]. The funding agency had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, or preparation and submission of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Jardin Dogan, M.Ed., Ed.S, is a second-year doctoral student in Counseling Psychology at the University of Kentucky. Her research interests connect to race-related trauma, and drug and sexual health-related disparities. Jardin hopes to explore coping strategies to combat the impact of racism, substance abuse, and incarceration on the functioning of Black couples and families.

Candice Hargons, Ph.D., is an assistant-professor in the Department of Educational, School, and Counseling Psychology at the University of Kentucky. Her research focuses on sex, social justice, and leadership – all with a love ethic.

Carolyn Meiller, M.S., is a third-year doctoral student in Counseling Psychology at the University of Kentucky. Her research interests include sexual experiences and pleasure. Carolyn is seeking to explore sexual pleasure among curvy, queer women for her dissertation.

Joseph Oluokun, B.A., is a second-year master’s student in Counseling Psychology at the University of Kentucky. Joseph’s research interests include racial microaggressions and their effect on minorities, specifically African Americans.

Chesmore Montique, M.A., is a first-year doctoral student in Counseling Psychology at the University of Kentucky. His research interests explore the mental health of Black women as impacted by their lived experiences with intersectional identities.

Natalie Malone, B.A., is a first-year doctoral student in Counseling Psychology at the University of Kentucky. Natalie is interested in exploring how intersections of identity create unique experiences for African Americans.

References

- Abrams JA, Maxwell ML, & Belgrave FZ (2018). Circumstances beyond their control: Black women’s perceptions of black manhood. Sex Roles, 79(3–4), 151–162. doi: 10.1007/s11199-017-0870-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen K, & Mitchell S (2015). Perceptions of parental intimate relationships and their effects on the experience of romantic relationship development among African American emerging adults. Marriage & Family Review, 51(6), 516–543. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2015.1038409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Awosan CI, & Opara I (2016). Socioemotional factor: A missing gap in theorizing and studying Black heterosexual coupling processes and relationships. Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships, 3(2), 25–51. doi: 10.1353/bsr.2016.002729201951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Awosan CI, & Hardy KV (2017). Coupling processes and experiences of never married heterosexual Black men and women: A phenomenological study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(3), 463–481. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagarozzi DA (2014). Enhancing intimacy in marriage: A clinician’s guide. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1978). The self-system in reciprocal determinism, American Psychologist, 33, 344–358. [Google Scholar]

- Benard AA (2016). Colonizing Black female bodies within patriarchal capitalism: Feminist and human rights perspectives. Sexualization, Media, & Society, 2(4). doi: 10.1177/2374623816680622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berends L, & Johnston J (2005). Using multiple coders to enhance qualitative analysis: The case of interviews with consumers of drug treatment. Addiction Research & Theory, 13(4), 373–381. doi: 10.1080/16066350500102237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beyers W, & Seiffge-Krenke I (2010). Does identity precede intimacy? Testing Erikson’s theory on romantic development in emerging adults of the 21st century. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25(3), 387–415. doi: 10.1177/0743558410361370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birks M, Chapman Y, & Francis K (2008). Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. Journal of Research in Nursing, 13(1), 68–75. doi: 10.1177/1744987107081254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R, & De Vries B (2001). Introduction perspectives on intimacy. Generations, 25(2), 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite SR, Delevi R, & Fincham FD (2010). Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students. Personal Relationships, 17(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01248.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Lucas KJ, & Tschann JM (2004). “The ball was always in his court”: An exploratory analysis of relationship scripts, sexual scripts, and condom use among African American women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28(1), 70–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00124.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Teti M, Massie JS, Patel A, Malebranche DJ, & Tschann JM (2011). “What Does it Take to be a Man? What is a Real Man?”: Ideologies of masculinity and HIV sexual risk among Black heterosexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 13(5), 545–559. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.556201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charleston K (2014). Act like a lady, think like a patriarch: Black masculine identity formation within the context of romantic relationships. Journal of Black Studies, 45(7), 660–678. doi: 10.1177/0021934714549461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JB, & Guy-Sheftall B (2009). Gender talk: The struggle for women’s equality in African American communities. New York: The Random House Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (2004). Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. New York: Routledge. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne SM, Padilla-Walker LM, & Howard E (2013). Emerging in a digital world: A decade review of media use, effects, and gratifications in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 1(2), 125–137. doi: 10.1177/2167696813479782 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duncombe J, & Marsden D (1993). Love and Intimacy: The gender division of emotion and ‘emotion work’ a neglected aspect of sociological discussion of heterosexual relationships. Sociology, 27(2), 221–241. doi: 10.1177/0038038593027002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin D (2001). What’s love got to do with it?: Understanding and healing the rift between black men and women. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JR, Reiber C, Massey SG, & Merriwether AM (2012). Sexual hookup culture: A review. Review of General Psychology, 16(2), 161–176. doi: 10.1037/a0027911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JR, Gesselman AN, Massey SG, Seibold-Simpson SM, & Merriwether AM (2018). Intimacy through casual sex: Relational context of sexual activity and affectionate behaviours. Journal of Relationships Research, 9. doi: 10.1017/jrr.2018.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goff B, Reisbig A, Bole A, Scheer T, Hayes E, Archuleta K, Henry S, Hoheisel C, Nye B, Osby J, Sanders-Hahs E, Schwerdtfeger K, & Smith D (2006). The effects of trauma on intimate relationships: A qualitative study with clinical couples. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(4), 451–460. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grange CM, Brubaker SJ, & Corneille MA (2011). Direct and indirect messages African American women receive from their familial networks about intimate relationships and sex: The intersecting influence of race, gender, and class. Journal of Family Issues, 32(5), 605–628. doi: 10.1177/0192513X10395360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hargons CN, Mosley DV, Meiller C, Stuck J, Kirkpatrick B, Adams C, & Angyal B (2018). “It Feels So Good”: Pleasure in Last Sexual Encounter Narratives of Black University Students. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(2), 103–127. doi: 10.1177/0095798417749400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helm KM, & Carlson J (Eds.). (2013). Love, intimacy, and the African American couple. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holland KJ, Lee JW, Marshak HH, & Martin LR (2016). Spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and physical/psychological well-being: Spiritual meaning as a mediator. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 8(3), 218. doi: 10.1037/rel0000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooks B (2004). We real cool: Black men and masculinity. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hook MK, Gerstein LH, Detterich L, & Gridley B (2003). How close are we? Measuring intimacy and examining gender differences. Journal of Counseling & Development, 81(4), 462–472. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2003.tb00273.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin S (2013). Qualitative secondary data analysis: Ethics, epistemology and context. Progress in Development Studies, 13(4), 295–306. doi: 10.1177/1464993413490479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR, & Loscocco K (2015). Black marriage through the prism of gender, race, and class. Journal of Black Studies, 46(2), 142–171. doi: 10.1177/0021934714562644 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kane CM (2000). African American family dynamics as perceived by family members. Journal of Black Studies, 30(5), 691–702. 10.1177/002193470003000504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S, & Floyd FJ (2001). The effects of negative racial stereotypes and Afrocentricity on Black couple relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(1), 110. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr ME, & Bowen M (1988). Family evaluation: The role of the family as an emotional unit that governs individual behavior and development. Markham, Ontario: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Yu T, & Brown GL (2016). Romantic relationship commitment behavior among emerging adult African American men. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(4), 996–1012. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, Barrett LF, & Rovine MJ (2005). The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: A daily-diary and multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 314. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, & Kleinman BM (2006). Intimacy in Personal Relationships In Vangelisti AL & Perlman D (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 637–653). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511606632.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence-Webb C, Littlefield M, & Okundaye JN (2004). African American intergender relationships a theoretical exploration of roles, patriarchy, and love. Journal of Black Studies, 34(5), 623–639. doi: 10.1177/0021934703259014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenton AP, Bryan A, Hastie R, & Fischer O (2007). We want the same thing: Projection in judgments of sexual intent. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(7), 975–988. doi: 10.1177/0146167207301019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RA (1978). Emotional intimacy among men. Journal of Social Issues, 34(1), 108–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1978.tb02543.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lima AC, Davis TL, Hilyard K, Jeffries WL, & Muilenburg JL (2018). Individual, interpersonal, and sociostructural factors influencing partner nonmonogamy acceptance among young African American women. Sex Roles, 78(7–8), 467–481. doi: 10.1007/s11199-017-0811-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn-Blake SM, & Darling CA (1993). Understanding the strengths of African American families. Journal of Black Studies, 23(4), 460–471. doi: 10.1177/002193479302300402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan-Lemal E, Toledo L, O’Daniels C, Villar-Loubet O, Simpson C, Adimora AA, & Marks G (2013). “A man’s gonna do what a man wants to do”: African American and Hispanic women’s perceptions about heterosexual relationships: a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health, 13(1), 27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta CM, Walls C, Scherer EA, Feldman HA, & Shrier LA (2016). Daily affect and intimacy in emerging adult couples. Journal of Adult Development, 23(2), 101–110. doi: 10.1007/s10804-016-9226-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moss BF, & Schwebel AI (1993). Defining intimacy in romantic relationships. Family Relations, 31–37. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/584918 [Google Scholar]

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, & Moules NJ (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry AR (2013). African American men’s attitudes toward marriage. Journal of Black Studies, 44(2), 182–202. doi: 10.1177/0021934712472506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph A (2018). When men give birth to intimacy: The case of Jay-Z’s “4:44”. Journal of African American Studies. 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12111-018-9418-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, & Shaver P (1988). Intimacy as an interpersonal process In Duck S, Hay DF, Hobfoll SE, Ickes W, & Montgomery BM (Eds.), Handbook of personal relationships: Theory, research and interventions (pp. 367–389). Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Rice K (2015). Pansexuality. The International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality, 861–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Rose T (2003). Longing to tell: Black women’s stories of sexuality and intimacy. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer MT, & Olson DH (1981). Assessing intimacy: The PAIR inventory. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 7(1), 47–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1981.tb01351.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seal DW, & Ehrhardt AA (2003). Masculinity and urban men: Perceived scripts for courtship, romantic, and sexual interactions with women. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 5(4), 295–319. doi: 10.1080/136910501171698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C, Oliver MB, & Campbell WK (1994). Perceived benefits and costs of romantic relationships for women and men: Implications for exchange theory. Personal Relationships, 1(1), 5–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1994.tb00052.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA & Blood EA (2016). Momentary desire for sexual intercourse and momentary emotional intimacy associated with perceived relationship quality and physical intimacy in heterosexual emerging adult couples. Journal of Sex Research, 53(8), 968–978. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2015.1092104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobo E (1993). Inner-city women and AIDS: The psychosocial benefits of unsafe sex. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 17(4), 455–485. doi: 10.1007/BF01379310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S (1998). Social exchange theories and sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 35(1), 32–43. doi: 10.1080/00224499809551915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stamps D (2017). The social construction of the African American family on broadcast television: A comparative analysis of The Cosby Show and Blackish. Howard Journal of Communications, 28(4), 405–420. doi: 10.1080/10646175.2017.1315688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens DP (2012). The influence of mainstream Hip Hop’s female sexual scripts on African American women’s dating relationship experiences In Paludi M (Ed.) The Psychology of Love, (pp. 69–83). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Terry G, Hayfield N, Clarke V and Braun V (2017) Thematic analysis In: Willig C and Stainton Rogers W, (Eds.) The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2nd. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter PB (2010). The influence of parental romantic relationships on college students’ attitudes about romantic relationships. College Student Journal, 44(1). [Google Scholar]

- Utley EA (2010). “I Used to Love Him”: Exploring the miseducation about Black love and sex. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 27(3), 291–308. doi: 10.1080/15295030903583531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein E, & Rosen E (1991). The development of adolescent sexual intimacy: Implications for counseling. Adolescence, 26(102), 331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Western B, & Wildeman C (2009). The Black family and mass incarceration. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621, 221–242. doi: 10.1177/0002716208324850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, Bowen A, Ross M, Timpson S, Pallonen U, & Amos C (2008). An investigation of a personal norm of condom-use responsibility among African American crack cocaine smokers. AIDS Care, 20(2), 225–234. doi: 10.1080/09540120701561288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis LA, & Clark LF (2009). Papa was a rolling stone and I am too: Paternal caregiving and its influence on the sexual behavior of low-income African American men. Journal of Black Studies, 39(4), 548–569. doi: 10.1177/0021934707299635 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo H, Bartle-Haring S, Day RD, & Gangamma R (2014). Couple communication, emotional and sexual intimacy, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40(4), 275–293. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2012.751072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]