ABSTRACT

This document gathers the opinion of a multidisciplinary forum of experts on different aspects of the diagnosis and treatment of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) in Spain. It has been structured around a series of questions that the attendees considered relevant and in which a consensus opinion was reached. The main messages were as follows:

CDI should be suspected in patients older than 2 years of age in the presence of diarrhea, paralytic ileus and unexplained leukocytosis, even in the absence of classical risk factors. With a few exceptions, a single stool sample is sufficient for diagnosis, which can be sent to the laboratory with or without transportation media for enteropathogenic bacteria. In the absence of diarrhoea, rectal swabs may be valid. The microbiology laboratory should include C. difficile among the pathogens routinely searched in patients with diarrhoea.

Laboratory tests in different order and sequence schemes include GDH detection, presence of toxins, molecular tests and toxigenic culture. Immediate determination of sensitivity to drugs such as vancomycin, metronidazole or fidaxomycin is not required. The evolution of toxin persistence is not a suitable test for follow up. Laboratory diagnosis of CDI should be rapid and results reported and interpreted to clinicians immediately.

In addition to the basic support of all diarrheic episodes, CDI treatment requires the suppression of antiperistaltic agents, proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics, where possible. Oral vancomycin and fidaxomycin are the antibacterials of choice in treatment, intravenous metronidazole being restricted for patients in whom the presence of the above drugs in the intestinal lumen cannot be assured. Fecal material transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with multiple recurrences but uncertainties persist regarding its standardization and safety. Bezlotoxumab is a monoclonal antibody to C. difficile toxin B that should be administered to patients at high risk of recurrence. Surgery is becoming less and less necessary and prevention with vaccines is under research. Probiotics have so far not been shown to be therapeutically or preventively effective. The therapeutic strategy should be based, rather than on the number of episodes, on the severity of the episodes and on their potential to recur. Some data point to the efficacy of oral vancomycin prophylaxis in patients who reccur CDI when systemic antibiotics are required again.

Key-words: Clostridiodes difficile, Clostridium difficile, Diarrhoea associated to C. difficile, Vancomycin, Metronidazole, Fidaxomicin, Fecal Material Transplantation (FMT), Bezlotoxumab, Vaccines, Probiotics, Monoclonal antibodies

RESUMEN

El presente documento recoge la opinión de un foro multidisciplinar de expertos sobre distintos aspectos del diangóstico y tratamiento de la infección por Clostridioides difficile (CDI) en España. Se ha estructurado alrededor de una serie de preguntas que los asistentes consideraron pertinentes y en las que se llegó a una opinón de consenso. Los principales mensajes fueron los siguientes:

CDI debe sospecharse en pacientes mayores de 2 años de edad ante la presencia de diarrea, ileo paralítico y leucocitosis inexplicada, aún en ausencia de los factores de riesgo clásicos. Salvo excepciones, es suficiente con una sola muestra de heces para su diagnóstico que pueden ser enviadas al laboratorio con o sin medio de transporte para bacterias enteropatógenas. En ausencia de diarrea, pueden ser válidos los isopados rectales. El laboratorio de microbiología debe incluir a C. difficile entre los patógenos buscados de rutina en pacientes con diarrea.

Las pruebas de laboratorio en diferentes esquemas de orden y secuencia incluyen la detección de GDH, la presencia de toxinas, las pruebas moleculares y el cultivo toxigénico. No se precisa la determinación inmediata de sensibilidad frente a fármacos como vancomicina, metronidazol o fidaxomicina. La evolución de la persistencia de toxina no es un test adecuado para el seguimiento del proceso. El diagnóstico de laboratorio de CDI debe ser rápido y los resultados informados e interpretados a los clínicos con carácter inmediato.

Además del soporte básico de toda diarrea, el tratamiento de CDI requiere la supresión de los agentes antiperistálticos, de los inhibidores de la bomba de protones y de los antibióticos, cuando sea posible. Vancomicina oral y fidaxomicina son los antibacterianos de elección en el tratamiento, restringiéndose metronidazol intravenoso para enfermos en los que no se pueda asegurar la presencia en la luz intestinal de los fármacos anteriores. El trasplante de materia fecal es el tratamiento de elección para pacientes con múltiples recurrencias pero persisten incertidumbres sobre su estandarización y seguridad. Bezlotoxumab es un anticuerpo monoclonal frente a la toxina B de C. difficile que debe administrarse a pacientes con alto riesgo de recurrencias. La cirugía es un procedimiento cada vez menos necesario y la prevención mediante vacunas se encuentra en fase de investigación. Los probióticos no han demostrado, hasta el momento, eficacia terapéutica ni preventiva. La estrategia terapéutica debe basarse, más que en el número de episodios, en la gravedad de los mismos y en la potencialidad de recurrir. Algunos datos apuntan a la eficacia de la profilaxis con vancomicina oral en pacientes que recurren cuando vuelven a precisar antibióticos sistémicos.

Palabras clave: Clostridiodes difficile, Clostridium difficile, diarrea asociada a C. difficile, vancomicina, metronidazol, fidaxomicina, Trasplante de materia fecal, bezlotoxumab, vacunas, probióticos, anticuerpos monoclonales

INTRODUCTION

Clostridiodes difficile (CD) is the leading cause of infectious diarrhea in adults in contact with the health-care setting [1, 2], but also an increasing proportion of C. difficile infections (CDI) are either community-acquired or of community onset [3-7]. In Spain, the estimated incidence of CDI acquired in relationship with HealthCare Facilities is 6,5 episodes per 10,000 patientdays of admission and 22.3 episodes per 100.000 inhabitants [8], but many episodes remain undetected. The underdiagnosis was evaluated in three different Nationwide studies in Spain. The results across these studies showed a decrease in missed diagnoses from 76% to 50% between 2008 and 2013 [8-11]. The underdiagnosis, in Spain, is due to the lack of clinical suspicion or to the use of insensitive diagnostic tests. In the European EUCLID study, that followed the methodogy of the Spanish Studies, the mean number of CDI episodes was of 7 episodes of CDI per 10,000 patient-bed days and it was estimated that 23% of the cases were missed [12]. Most cases described in Spain have mild or moderate severity, are health care-associated, and have a recurrence frequency ranging from 12% to 18% [6, 11, 13].

Recurrent CDI (rCDI) represents an incremental morbidity and cost for patients and institutions. It falls not just on the length-of stay, which has the highest weight, but also on re-hospitalisation, serious complications, laboratory tests and medications [14, 15]. In addition to the economic burden, an important factor that needs to be taken into account in patients suffering from rCDI is the impact on the quality of life (QoL) of this disease [16, 17].

Accurate diagnosis of CDI is suboptimal and laboratory methods to diagnose the disease can be misleading due to the development in the last years of multiple tests with different sensitivities, specificities and targets (bacterium, toxins, cell membrane enzyme, toxin genes) [8, 10, 18, 19].

Finally, current recommendations for treatment vary according to the country issued and the clinical definition, and have been linked mainly to the number of episodes of the patient and the severity of CDI. However, treatment of patients with CDI recurrences and those with severe complicated forms is not so clear and is based on limited clinical evidence, and new treatments or strategies are needed [2, 20, 21]. Several recently completed prospective, randomized, double blind clinical trials have showed that fidaxomicin can be as effective as vancomycin in achieving clinical cure and superior in preventing recurrence [22, 23]. New published evidence has demonstrated that patients receiving bezlotoxumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody especific against the toxin B of CD, plus antibiotic treatment against CDI had a 40% of relative reduction of rCDI at 12 weeks [24].

However, the administration of antimicrobial agents to treat rCDI has been put into perspective with another therapeutic and preventive alternative: Fecal Material Transplantation (FMT) [25-27]. FMT is effective in reducing the incidence of multiple recurrences, however, the technique is cumbersome, not available in the majority of institutions and raises concerns related to the best way, the best dose and the potential transmission of currently unknown microorganisms [28-37]. Also, in the near future, there might be the possibility of prevention with vaccination [38, 39] or with antibiotics.

Aware of the problem of CDI, a panel of experts were convened to develop an opinion document with recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of CDI, based on the best available evidence for achieving the greatest clinical efficacy adapted to the situation in Spain. The present document is structured in several questions, agreed among the participants, about controversial issues in the diagnosis and treatment of CD in our country. Every answer has a review of the evidence supporting or refuting the issues raised. Finally, the recommendations based on this review are issued.

QUESTION 1. When should CDI be suspected in patients older than 2 years?

Traditional risk factors for acquision of CDI are antimicrobial treatment within the previous 6-8 weeks, advanced age and prolonged hospital stay [6, 40-48]. However, recent studies have shown that a significant proportion of CDI episodes affect patients without any of these risk factors, thus outlining the need for a greater awareness of this disease. In 2008, a study performed in more than 100 Spanish hospitals showed that most patients unsuspected to have CDI did not have traditional risk factors for CDI such as advanced age or hospitalization [10]. A two-point prevalence study performed in Spain and other European countries in January and July 2013 showed similar results [8, 12]. CDI is also relatively common in nonhospitalized patients both with prior contact with the health care system or without [6]. When compared with patients with hospital-acquired CDI (HA-CDI), those with community-acquired CDI (CA-CDI) were younger, more likely to be female, had lower comorbidity scores, and were less likely to have severe infection or have been exposed to antibiotics [6, 49]. One North-American population-based study performed in the period 2004-2007 also showed a high incidence rate for CA-CDI and almost a third of these episodes were from patients that had not received antimicrobials in the six months prior to the diagnosis, and 17% did not have any traditional risk factors for CDI [50]. Another study by Naggie et al, showed that 40% of the patients with CA-CDI had not received antimicrobials prior to diagnosis [51]. In a recent study published by Spanish authors, the use of rifaximin in cirrhotic patients was associated with breakthrough CDI [52]. This evidence supports that common risk factors for CDI may not be present in all patients, therefore each probable case has to be evaluated in an individualized manner and in the presence of a diarrheic episode all patients should be suspected of CDI until proven otherwise.

Some people become carriers of CD or develop a mild, selflimited diarrhea while others develop severe colitis and may have multiple relapses of the disease [53, 54]. Patients with CD intestinal disease usually have mild or severe diarrhea and abdominal pain, low-grade to high-grade fever, and leukocytosis; they may have hypovolemia, shock, and hypoalbuminemia. Some patients develop fulminant colitis associated with a colonic ileus, in which case the patient may not have diarrhea. Physicians rarely suspect CD disease in the absence of diarrhea. A colonoscopy to look for pseudomembranes and to obtain a stool sample is not necessary to make or confirm the diagnosis in the majority of the episodes and may even be associated with adverse events. A computed tomography scan may be diagnostic of CD colitis, provided physicians think of this disease in the absence of diarrhea. Patients with acute toxic megacolon may have abdominal pain, fever, leukocytosis [55], and hypoalbuminemia, but they may not have diarrhea. Many clinicians would suspect ischemic colitis, rather than CD colitis. This form of CD disease has a very high mortality rate and a poor response to vancomycin and metronidazole [56, 57].

One of the most uncertain points of CDI diagnosis is the clinical significance of the detection of a toxigenic CD strain in a diarrheic patient aged less than 2 years. The low number of toxin receptors in the intestinal lumen in patients aged less than 2 years and the high frequency of viral pathogens producing diarrheic episodes indicate the doubtful role of CD in the diarrheical diasease in this age group. In a study performed in a Madrid hospital, all diarrheic stool samples received from children younger than 2 years old were screened for CD. Positive (cases) and negative (controls) children were compared and also cases receiving or not specific anti CDI treatment. No differences in clinical behaviour were detected and all the patients, including CD cases, independently of the administration of metronidazole, were cured of the diarrheic episode [58]. A group of experts recently found a lack of evidence of an unmet need to treat CDI infections in infants under 2 years of age [59].

In conclusion, data in the literature supports that CDI should be suspected in diarrhoeic episodes in patients of any age except for those younger than 2 years even in patients with or without traditional risk factors for CDI. Some patients may not have diarrhea, such is the case of colonic ileus or “unexplained” leukocytosis, making the clinical diagnosis more difficult and sometimes resulting in fulminant colitis

QUESTION 2. Which is the optimal number of stool specimens that should be sent to the Microbiology laboratory for the diagnosis of CDI?

The positivity rate of subsequent specimens from patients with a first negative sample is very low and, therefore, testing a second specimen from a negative patient is more likely to be a false-positive [60-62].

International guidelines of three of the most important societies, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM) recommend to test only one stool specimen per patient for the diagnosis of CDI [20, 63]. The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) does not recommend repeated sample submission during the same episode in a endemic situation although it may be useful in a epidemic situation [64].

In conclusion, data in the literature supports that the best cost-effective number of stool specimens needed for the diagnosis of CDI is one stool specimen and, only exceptionally, two or more stool samples.

QUESTION 3. Which transportation media can be used to send specimens to the laboratory for CDI diagnosis?

Although CD is an anaerobic pathogen, the ability of this microorganism to form spores allows the transportation of specimens for the diagnosis of CDI in aerobiated containers without any media to maintain viability of the microorganism [65-68]. Guidelines performed by IDSA and SHEA societies recommend transporting stool specimens in clean, watertight containers, without transport medium to diagnose CDI [63]. However, in a great number of laboratories, stool samples with a clinical request for aerobic enteropathogens like Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., or Campylobacter spp. are sent to the Microbiology laboratory preserved in transport media. One of the most common media used is Cary-Blair medium, that prevents overgrowth of most Enterobacteriaceae and is effective in the preservation for long periods of common enteropathogens. Additionally, this medium does not affect the performance of four different diagnostic methods used to diagnose CDI (glutamate dehydrogenase immnunoassay, toxins A and B immunoassay, cell culture cytotoxicity assay and real-time PCR targeting the toxin B gene) [69-71] Samples transported in sporicidal medium like formaldehyde for parasites must be rejected. Samples must be sent as soon as possible to the microbiology laboratory. In general, it is recommended to preserve samples at 2-8ºC the first 48-72 hours or frozen at -60 to -80ºC if samples will not be processed within the following 72 hours [19].

In conclusion, data in the literature supports that both, samples without any transport medium and samples with transport medium for aerobic enteropathogens, such as Cary-Blair, are suitable for the diagnosis of CDI.

QUESTION 4. Should stool specimens without a C. difficile request be processed for C. difficile diagnosis?

As previously recommended, clinicians should suspect CDI in any patient suffering diarrhea with or without traditional risk factors for this disease, including outpatients. However, clinicians are not always aware of the presence of common or uncommon risk factors for this illness and, even if it is the case, clinicians sometimes do not remember to include the request for CDI diagnosis in samples sent to the Microbiology laboratory. Clinical misdiagnosis can occur even in patients with traditional risk factors like hospitalized patients. Even in the best scenario for CDI recognition, as is the case of nosocomial diarrhea, the clinical suspicion of CDI is far from optimal, where about 30% of nosocomial CDI episodes are missed due to a lack of processing specimens for CDI [9, 55].

In conclusion, it seems clear that the microbiology laboratory has an important role in improving the diagnosis of CDI. Since the degree of suspicion of physicians may be insufficient, the microbiologist should consider, with the available information, to perform diagnostic techniques for C. difficile in samples of unformed faeces regardless of what was requested

QUESTION 5. Should specimens other than diarrheic stool specimens be processed for CDI?

There is a general consensus in all international guidelines that watery or loose stools are the only specimens that should be collected to diagnose CDI in diarrheic patients with suspicion of this disease, in day to day clinical practice [63, 64]. However, CD can produce infections in which patients do not develop diarrhea, like ileus, toxic megacolon, pseudomembranous colitis without diarrhea or abdominal distension. In these cases, it may not be possible to obtain an unformed stool specimen for a CDI diagnosis. In these situations, diagnostic procedures recommended by international guidelines are not applicable. English guidelines performed by the Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infection (ARHAI) recommend using in these situations procedures such as colonoscopy, white cell count, serum creatinine or abdominal computerized tomography scanning [72]. On the other hand, guidelines performed by the SHEA and IDSA societies recommend rectal specimens obtained by means of cotton swabs for the etiologic diagnosis of CDI [63, 64]. Guidelines from the ASM do not recommend rectal specimens in these situations and only suggest using formed stool specimens, when present, and after consensus with clinicians [73].

Culture of rectal specimens are as sensitive as stool culture for the diagnosis of CDI [74], and the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of testing perirectal swabs versus stool specimens using PCR are similar [75]. The culture of colon biopsies obtained by colonoscopy has been an acceptable procedure for diagnosis of CDI for a long time, however, diagnosis based on stool specimens, which are less invasive and cheaper, could be a better option for CDI diagnosis [69]. To clarify this question, a comparison between diagnostic methods in both colon biopsies and stool specimens was evaluated in a retrospective study in Spain. The study showed that sensitivity of colon biopsies to diagnose CDI (21.3%) was significantly lower than that obtained using simultaneous stool specimens (94.7%) [76].

In conclusion, data from the literature shows that rectal specimens are useful for CDI diagnosis in patients in which stool specimens cannot be obtained. Furthermore, stool specimens are more sensitive than colonic biopsies for the diagnosis of CDI in patients with colitis.

QUESTION 6. What combination of laboratory tests is most cost effective and therefore recommended for an optimal diagnosis of CDI?

Currently, there is no diagnostic test for CDI that alone can be sufficiently cost-effective to be used in the rapid diagnosis of the disease. As a consequence, diagnostic algorithms have been designed to take advantage of the benefits of each diagnostic test [77-79]. Rapid detection of toxins A and/or B can be performed with enzyme immunoassays (EIAs). At first, laboratories used EIAs that detected only toxin A but, with the dissemination and higher frequency of strains toxin A-/toxin B+ producing CDI, these were replaced by EIAs capable of detecting both toxins [80-83]. Some comparative studies have shown that EIAs have sensitivity values of 40-60% when compared with toxigenic cultures [84-90]. On the other hand, the specificity of most of these tests is higher than 90%. The American Society for Microbiology, ASM, considers these tests as techniques with low sensitivity and strongly recommends that these tests are not used as stand-alone tests [73]. In Europe, an analysis performed by the ESCMID committee concerning 13 commercial EIAs that detect toxins A and/or B also showed the deficiency of sensitivity of these tests and concluded that CDI diagnosis should be performed with more sensitive tests [64].

Detection of the enzyme glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), a protein produced in large quantity by most of the CD strains (toxigenic and non-toxigenic), is another rapid test that allows the detection of CD. The sensitivity of this test is higher than toxin detection alone, between 85%-95%, however the specificity and positive predictive value are relatively low since it can detect strains that produce toxins as well as nonproducing strains [91, 92]. Due to the relative low specificity of tests based in GDH detection alone, main societies do not recommend the latter as single tests for rapid diagnosis of CDI [63]. Currently, there are commercialized diagnostic tests that include detection of both GDH antigen and toxins A and/or B, with the main advantage of offering results simultaneously.

In recent years, the CDI diagnostic conundrum has been dramatically transformed by the development of commercial nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). NAATs are molecular assays that mostly utilize real-time PCR or loop-mediated isothermal amplification to directly detect the tcdA or tcdB genes encoding toxin A or B, respectively, from stool specimens [93-103]. Due to the rapid uptake of NAATs there are now a great number of commercial products in the market, most of them FDA approved, like the BD MAX system (Becton Dickinson), Xpert® C. difficile (Cepheid), Prodesse® ProGastroTM CD (Gen-Probe) and Illumigene® C. difficile (Meridian), with an average of turnaround time between 45 min – 3 hours. The majority target the tcdB gene, and some can detect one or both genes of the binary toxin, even hipervirulent ribotype 027 strains that have mutations or deletions of the repressor gene tcdC [104, 105]. Sensitivity values of most of these techniques are very high with values greater than 90% and specificities greater than 98% when compared with toxigenic culture, however, the positive predictive value of NAATs for CDI can be low to moderate (80%-95%), depending upon disease prevalence and the limit of detection of the assay [21]. The other problem of NAATs is their high cost when used as stand-alone tests. This limitation precludes them as a systematic alternative for diagnosis of CDI in most laboratories [104].

The cytotoxin assay has been traditionally considered the gold standard for CDI diagnosis. This technique uses tissue cultures to detect CD toxins from diluted stool specimens. This assay is highly specific because it uses specific antibodies for neutralization. However, numerous studies have shown that the cytotoxin neutralization assay is only 65 to 80% sensitive to detect toxigenic CD isolates in comparison to toxigenic culture, which is performed by isolating CD on selective media and demonstrating cytotoxin production by the cultured organism [106-108]. A rising group of experts considers that a negative cytotoxin assay with a positive toxigenic culture indicates a low concentration of free toxin in the stools, not able to be detected by the cytotoxic assay alone [79, 109]. For this reason, the ASM recommends using toxigenic culture or NAATs as a confirmatory test of the rapid algorithms [21].

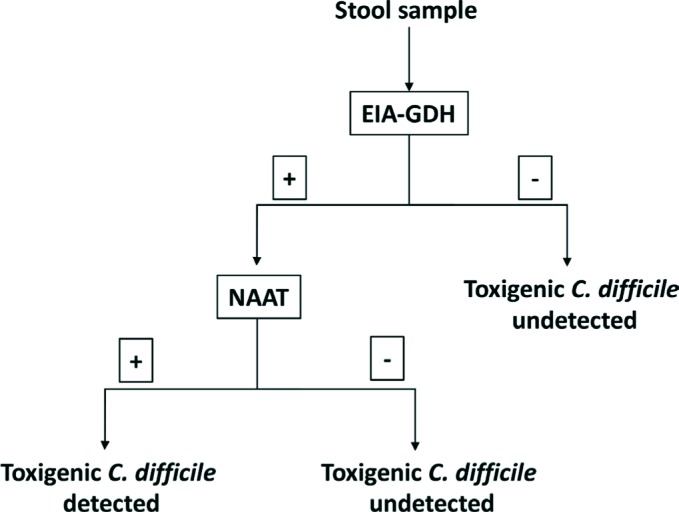

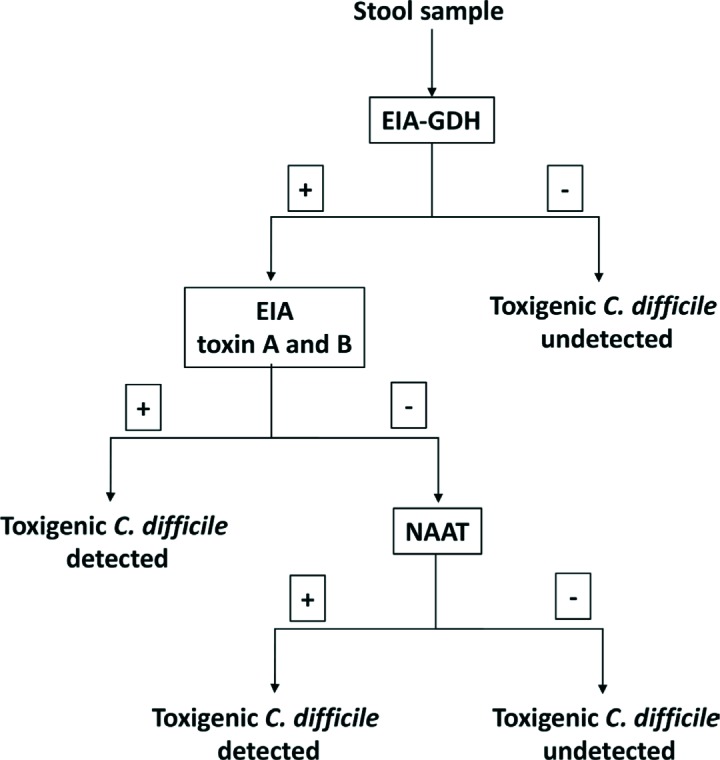

Due to the limitations of each of the individual tests for a rapid and correct diagnose of CDI, several multi-step algorithms have been proposed (figures 1 and 2). These algorithms have as screening test the detection of GDH by EIA due to its high sensitivity to detect CDI [110-113]. As most specimens are negative, the GDH screening step substantially reduces the number of specimens that require evaluation with more specific methods. Since both toxigenic and nontoxigenic CD strains express GDH, a positive GDH EIA requires confirmation with a sensitive assay for detection of toxin A or B or their genes. Overall performance including turnaround time of a GDH-based algorithm depends on the secondary tests used to follow up a positive GDH result. GDH detection followed by a NAAT is considered a two-step algorithm and has approximately a 90% sensitivity, and specificity higher than 99% [19]. A three-step algorithm detects toxins A and/or B between the GDH detection and NAATs, reducing almost by 50% the number of molecular tests needed [19]. However, in the recent update of CDI guidelines published recently by IDSA and SHEA the recommendation is to use a stool toxin test as part of a multistep algorithm (i.e., GDH plus toxin; GDH plus toxin arbitrated by NAATs; or NAATs plus toxin) [21]. These procedures have been evaluated by several authors and have a sensitivity of 85-90% and specificity greater than 99% [77, 85, 95, 114-117].

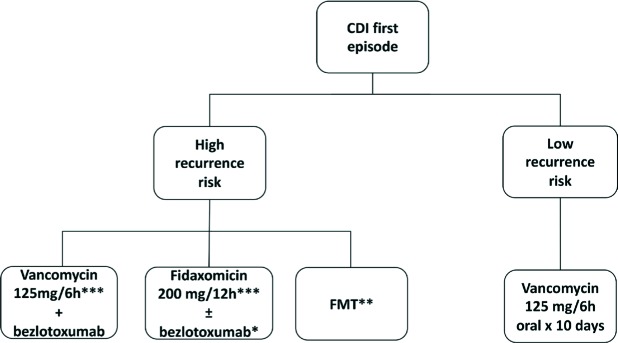

Figure 1.

A rapid, cost-effective algorithm for the diagnoses CDI (two steps)

EIA-GDH: Detection of glutamate dehydrogenase by enzyme immunoassay

NAAT: nucleic acid amplification test

Figure 2.

A rapid, cost-effective algorithm for the diagnoses CDI (three steps)

EIA-GDH: Detection of glutamate dehydrogenase by enzyme immunoassay

EIA toxin A and B: Detection of toxin A and B by enzyme immunoassay

NAAT: nucleic acid amplification test

Another traditional and less costly method for the diagnosis of CDI is the toxigenic culture; it has increased sensitivity over cytotoxicity and it is based on the detection of toxin production in the microorganism after isolation in culture. A downside to this technique would be the 48 hours to obtain bacterial growth. Published literature shows a controversy in the diagnosis of CDI in patients in which the results of the cytotoxic assays differ from the toxigenic culture. In a study by Reigadas et al, the authors observed that CDI episodes positive by cytotoxicity assay were more severe than those positive only by toxigenic culture. However, in their study, there were a significant proportion of CDI cases (31.9%) that would have been missed if only cytotoxicity had been considered, including 10% of severe CDI cases and one patient with pseudomembranous colitis. Additionally, in the same study, 45% of the CDI cases had a negative toxin portion EIA, which exemplifies the need for further testing samples with a positive GDH portion and a negative toxin EIA portion test, by PCR or toxigenic culture [118].

Some situations call for a change in the diagnostic algorithm. This is the case of CDI due to ribotype 027 strains that are usually more severe, with a higher transmission and recurrence rate than CDI caused by other ribotypes. In case of suspicion of an outbreak due to this ribotype, it is recommended to perform a rapid molecular test that specifically detects this ribotype [19, 119].

In conclusion, data reported in the literature shows that detection of GDH by EIA as a screening test followed by a rapid confirmatory technique as a NAAT alone or together with the detection of toxins by EIA is the most cost-effective procedure for the rapid diagnosis of CDI (figure 1 and 2). Toxigenic culture is a slow but sensitive and low-cost method for detecting CDI in patients with negative EIA or cytotoxicity.

QUESTION 7. When and how to perform antimicrobial susceptibility tests to C. difficile isolates?

For a long time, the susceptibility testing of the traditional antimicrobials metronidazole and vancomycin was not even recommended because the universal activity of these drugs was not questioned. However, different in vitro susceptibility studies performed during the last years have showed the existence of toxigenic isolates of CD resistant to these drugs.

In 1997, Barbut and colleagues found one resistant strain showing an MIC to metronidazole of 16 mg/L by the agar dilution method [120]. During the period 1993-2000, Peláez and colleagues [121] detected 26 isolates resistant to metronidazole from 415 isolates tested (6.3% of resistance, MICs: ≥32 mg/L, agar dilution method) in Spain. A posterior analysis performed by Peláez et al. showed that resistance to metronidazole was heterogeneous and that it can be lost in strains after prolonged periods of storage due to freezing and thawing [122]. In an Israelite study performed, authors described a 2% of resistance to metronidazole (1/49 isolates, MIC: ≥32 mg/L, E-test method) [123]. A similar resistance rate was found in toxigenic strains isolated during 2004 to 2006 in Ontario, Canada (19/1,080 isolates, MICs: ≥32 mg/L, E-test method) [124]. Recently, Huang and colleagues reported a 23.1% of resistance to metronidazole in primary fresh toxigenic C. difficile strains isolated from 2008 to 2009 in China (18/78 isolates, MICs ≥32 mg/L, E-test method) [125]. As occurred in the Spanish study, the Canadian and Chinese isolates had such an heterogeneous resistance that most of the resistant isolates turned into sensitive to metronidazole after serial passages [122, 124]. Although not as frequent, isolates of CD with intermediate resistance to vancomycin (MIC>2 mg/L) have been reported [126-129]. On the other hand, fidaxomicin has shown a good activity against CD with most isolates having MICs lower than 1 mg/L being the highest MIC ever reported, to our knowledge, of 2 mg/L [130-137].

Concentration in colonic mucosa of metronidazole and its metabolite hydroxymetronidazole is considered bactericidal in patients with acute disease receiving oral or intravenous metronidazole, but as the diarrhea improves neither substance is detectable in the faeces of diarrhea caused by CD (mean concentration of 9.3 µg/g in watery stools and of 1.2 µg/g in formed stools)[138, 139]

This finding has led to the EUCAST committee to decrease the metronidazole breakpoint from 16 mg/L to 4 mg/L [140]. Conversely, fecal levels of vancomycin and fidaxomicin in the colon lumen are greater than metronidazole with concentrations of 64-760 µg/g on day 2 and 152-880 µg/g on day 3 post-treatment for vancomycin and as high as 3,000 mg/L for fidaxomicin [120] .

Although Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [126] guidelines do not recommend routine susceptibility testing for CD isolates, because correlation of MICs with clinical failures has not been established, they advocate in performing an annual surveillance testing to detect emerging resistance. The surveillance should be done by the hospital laboratory if expertise is available or, if not, by a reference laboratory. If possible, the guidelines recommend to test isolates collected over several months and stored until a total of 50-100 strains are available for later batch testing using preferably an agar dilution method [126].

In conclusion, data in the literature suggests that sensitivity testing should be performed annually to detect the emergence of resistance or in specific situations and in reference laboratories, but not on a routine daily basis

QUESTION 8. Is it necessary to follow-up patients with CDI with laboratory tests?

Generally, in non-complicated CDI cases, the therapeutic response for CDI involves the resolution of fever (if present) on the first day and of diarrhea before the fourth or fifth day [131]. This clinical resolution of the disease may not be accompanied by a microbiological clearance of CD toxins, as CD can survive in the lumen of cured patients during several weeks or months [132, 133]. In a study performed in healthy patients with previous recurrent CDI, authors found that persistence of spores of CD by the end of antibiotic therapy occurred in 56% of patients receiving metronidazole and 43% receiving vancomycin [134]. A similar observational study showed that nearly 20% of patients successfully treated for CDI had detectable spores in stool specimens at the time of the resolution of the diarrhea and it increased to 56% one to four weeks later [141]. The lack of correlation demonstrated in these studies between clearance of colonic CD and resolution of CDI has led to international guidelines to recommend not to use culture or toxin detection to follow-up the evolution of patients with CDI [20, 52]. In order to reduce false positives, some experts suggest that microbiological laboratories reject stool samples from patients treated for CDI with a microbiological diagnosis in the previous seven days [19], as well as from asymptomatic patients (unless suspicion of ileum or toxic megacolon) [21].

In conclusion, data in the literature shows that detection of toxigenic C. difficile from stool specimens is not a good method to follow-up the evolution of patients with CDI and should not be performed routinely.

QUESTION 9. When and how to report clinicians the results of laboratory tests for CDI?

Early recognition of an episode of CDI is a critical step to optimize the treatment of CD and to control the transmission to other patients, and must be based in three mainstays: a correct suspicion of the illness by clinicians, an accurate and rapid laboratory diagnosis of CDI, and a rapid and effective transmission of information of these results to the attending physician, infection prevention officer, and nursing staff [20, 52]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends to work with microbiology laboratories to ensure rapid reporting of test results for CDI, including weekends and holidays, and to ensure that there is a process for providing results to the patient care area so that isolation precautions can be initiated promptly (Center for Diseases Control and Prevention, Guidelines for preventing transmission of MDROs, 2006) [135]. Due to the fact that CD is able to produce spores that persist in the environment for many months and are resistant to cleaning and disinfectant measures, this pathogen is highly transmissible [132, 133]. Transmission of CD to the patient via transient hand carriage on healthcare workers´ hands is thought to be the most likely common way of transmission [136]. Some prominent authors and scientific societies such as the SHEA, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, the CDC, the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America [137, 138, 142-146] recommend several points to the health care facilities referring to the quarantine of CDI patients, use of antiseptic procedures such as the utilization of disposable gloves, mask and gown and hand-washing with soap and water, cleaning of patient-care equipment (such as thermometers, stethoscopes, etc.) before it is used with another patient, to enhance environmental cleaning with diluted bleach from all patient contact surface areas, to restrict the use of antimicrobials implicated as risk factors for CDI, to provide an easy laboratory access for prompt and active surveillance toxin B detecting at the earliest indication of a case of CDI and to use rapid and accurate tests to diagnose CDI in the laboratory.

Another important issue is that rapid and accurate laboratory recognition of a CDI episode is a key step to optimize the treatment of patients with CDI. Rapid report of a positive result can facilitate a prompt treatment that avoids the risk that an initial mild CDI episode may progress to severe colitis and toxic megacolon [147]. Delayed diagnosis can increase the time of patient exposition to inappropriate drugs as antiperistaltic or narcotics that can complicate CDI [148]. Similarly, fast information of a negative result favors the withdrawal of antimicrobials in patients with empiric treatment for CDI [52].

In conclusion, data from the literature suggests that rapid laboratory recognition of CDI is crucial for the control and management of this illness. Preliminary phone information of results obtained from the rapid diagnostic tests to the appropriate health care workers is recommended. Ideally, this information should be accompanied by test interpretation and treatment advice

THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS FOR CDI

QUESTION 10. What is the basic support approach for the treatment of patients with CDI?

The basic support approach for the treatment of patients with CDI include: 1) a standard supportive care for patients who are hemodynamically unstable, consisting of rapid fluids and electrolyte intravenous replacement. 2) avoidance of the following precipitating factors: a) agents such as narcotics and loperamide that inhibit intestinal peristalsis, retain intestinal toxins, and increase the risk of toxic megacolon [149-151]; b) concomitant broad-spectrum antibiotics for other concurrent infections [an early switch to reduced-spectrum antibiotics should be performed if complete suspension of the treatment is not possible)]; and c) anti-ulcer medication, especially proton pump inhibitors (PPI)[152, 153].

In conclusion, the basic support approach for patients with CDI includes: fluids and electrolyte replacement, and removal of intestinal peristalsis inhibitors, anti-ulcer medication, and concomitant antibiotics, when feasible.

QUESTION 11. What are the antibiotics of choice for CDI treatment?

The choice of initial antibiotic therapy for CDI depends on the severity of disease, the possibility of oral therapy, and the potential risk for recurrence. Initially, the first prospective, randomized studies in which patients were not stratified by disease severity demonstrated that both oral metronidazole and oral vancomycin were equally effective, over 90%, in the first episode and first recurrence [127, 128]. However, when patients were stratified based on the severity of the infection, vancomycin had a clinical response significantly better than metronidazole in severely ill subjects (97% versus 76%, P = 0.02) [130]. More recent studies have demonstrated that vancomycin provides superior cure rates compared with metronidazole, with reduced side effects, even in mild cases [154, 155].

The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) Guidelines in 2014 recommended metronidazole as first-line treatment for non-severe CDI and vancomycin as the first choice for severe CDI [20]. Nevertheless, results from a meta-analysis of large multicenter randomized controlled trials (RCT) showed that metronidazole is inferior to vancomycin in the treatment of CDI (non-severe and severe combined, with severe CDI defined as a white blood cell count ≥10,000/mm3, ten or more bowel movements per day, and severe abdominal pain)[154].

Fidaxomicin is a macrocyclic antibiotic approved in the USA and in Europe for the treatment of CDI [156]. Two completed prospective, randomized, double-blind, clinical trials showed that the rates of clinical cure after treatment with oral fidaxomicin (200 mg twice daily for 10 days) were noninferior to those after treatment with oral vancomycin (125 mg four times daily for 10 days); at the same time, a significant reduction in the rates of recurrence with an increase in the rate of sustained responses was also observed [22, 23]. Oral fidaxomicin is well tolerated, with a safety profile comparable to that of oral vancomycin. There are no differences in the incidence of death or serious adverse events between the two drugs. A downside is that the cost of fidaxomicin is much higher [23, 157]. However, in a recent Spanish study, using a cost–utility analysis model, it has been observed that fidaxomicin is more cost-effective than vancomycin for treatment of CDI in patients with cancer, renal impairment, and/or with concomitant antibiotic treatment [158]. Subsequently, two other studies in patients with cancer or concomitant antibiotic treatment have demonstrated a significant superiority of fidaxomicin over vancomycin [157, 159].

Since the publication of the ESCMID guidance document in which fidaxomicin was reserved for patients with relapsing CDI, a published meta-analysis and indirect treatment comparison suggested that fidaxomicin may be considered as firstline therapy for CDI in patients with a high risk of recurrence [160, 161]. In this regard, recently published IDSA guidelines recommend vancomycin or fidaxomicin for best treatment of initial CDI. The dosage recommended is: vancomycin 125 mg orally 4 times per day or fidaxomicin 200 mg twice daily for 10 days (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence][21].

Severe CDI cases may be treated with either oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin. A recent prospective, multicenter study demonstrated that courses with either antibiotic resulted in similar treatment outcomes for patients afflicted with severe CDI [21, 162]. When oral treatment is not possible, intravenous metronidazole should be used.

In conclusion, oral vancomycin is the recommended drug for an initial CDI episode; oral fidaxomicin should be considered in initial CDI episodes with a high risk of recurrence. In view of the evidence described above, the opinion of this group of experts is that the use of metronidazole should be restricted to situations in which vancomycin or fidaxomicin are contraindicated or an oral administration is not possible. Combination therapy (i.e. vancomycin and metronidazole) is not recommended in patients with severe CDI, with the exception of severe cases complicated with ileus

QUESTION 12. What additional antibiotics are being studied for the treatment of CDI?

Additional antibiotic options to the ones cited above exist, such as rifaximin [163-165], nitazoxanide [166-168], fusidic acid [169], tigecycline [170, 171], and teicoplanin [128, 172]; however, we do not recommended any of those for routine CDI treatment. Their use in the treatment of recurrences might be overshadowed by the efficacy of the currently available strategies described above. Moreover, there are reports of resistance development to rifaximin [52, 173] and fusidic acid [169], which further discounts the use of these antibiotics as treatment options for CDI in any episode.

Novel antibiotics include cadazolid, a new oxazolidinone. Cadazolid is an inhibitor of CD protein synthesis, causing more suppression of toxin production and spore formation than vancomycin and metronidazole. In pre-clinical studies, cadazolid showed a potent bactericidal in vitro activity against CD (MIC90 of 0.25 mg/L) and a low propensity for resistance development [174-176]. The results for the IMPACT I and IMPACT II phase 3, randomized clinical trials were recently published [177]. While safe and well tolerated, cadazolid failed to achieve the primary end-point of non-inferiority vs. vancomycin for clinical cure [177]. As a result, to the best of our knowledge, efforts to commercialize cadazolid for CDI have been halted.

Ridinilazole is another novel antibiotic currently undergoing clinical trials for the treatment of CDI. The precise mechanism of action of this antibiotic is not clear, however, it appears to impair cell division [178]. With limited activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative intestinal aneaerobes and a low MIC (MIC90 of 0.125 mg/L) for CD, ridinilazole appears to be a promising candidate for treating CDI. A phase 2, randomized clinical trial comparing ridinilazole with vancomycin for the treatment of CDI demonstrated non-inferiority and a statistically significant superitory at the 10% level. Moreover, the antibiotic was well tolerated with an adverse profile similar to that of vancomycin [179]. Phase 3 clinical trials comparing ridinilazole and vancomycin are ongoing [180].

In conclusion, data from the literature suggests that rifaximin, nitazoxamide, fusidic acid, tygecicline, and teicoplanin are currently not considered as therapy options for CDI, especially since new treatments and strategies for rCDI reduce the risk of recurrence. Cadazolid has failed to achieve the primary end-point of non-inferiority vs. vancomycin for clinical cure in a recent published clinical trial. Ridinilazole is a promising antibiotic with phase 3 clinical trials recruiting patients at present to demonstrate non-inferiority over vancomycin for the treatment of CDI.

QUESTION 13. What are the contributions of bezlotoxumab to the treatment of CDI?

Bezlotoxumab is a recombinant human IgG1/kappa isotype monoclonal antibody approved globally in 2017 for use as an adjunctive treatment in patients at risk for rCDI [181]. Bezlotoxumab binds to regions of the combined repetitive oligopeptide domains of toxin B that partially overlap with putative receptor binding pockets. This monoclonal antibody blocks the action of C. difficile toxin B and potentially averts the damage and inflammation that can lead to the symptoms associated with CDI [182].

In two global, phase III trials (MODIFY I and MODIFY II), bezlotoxumab demonstrated significant reductions in CDI recurrence compared with placebo (17% vs 28% in MODIFY I and 16% vs 26% in MODIFY II; P < .001) in adults receiving antibiotic treatment for primary CDI or rCDI [183]. In a secondary analysis, bezlotoxumab demonstrated better efficacy results in reducing CDI recurrence in a group of patients at high risk for CDI recurrence (patients with previous CDI episodes, severe CDI, older age (≥65 years old), and infection with hypervirulent strains]. Bezlotoxumab also reduced rCDI, FMT, and CDI-associated 30 day re-admissions in participants with risk factors for rCDI. As a result, the Spanish therapeutic positioning report (IPT) [184] recommends the use of bezlotoxumab as adjuvant therapy for CDI treatment in patients at high risk of recurrence, including patients ≥65 years old with a previous CDI episode in the last six months, immunosuppressed patients, patients with CDI caused by hypervirulent strains (such as 027 and 244), patients with severe CDI (Zar ≥2), and patients that exhibit a high probability of recurrence as evaluated by externally validated predictor models.

In conclusion, the monoclonal antibody bezlotoxumab is the first approved treatment for the prevention of CDI recurrence. It has demonstrated a 40% reduction of CDI recurrence when compared to placebo. Its efficacy is higher in sub-groups of patients at greater risk for recurrence

QUESTION 14. How should bezlotoxumab be used in clinical practice at present?

The efficacy of bezlotoxumab has already been discussed above. A single injection significantly decreases the incidence of recurrences and that difference has been maintained in subgroups of special populations such as immunosuppressed, transplanted, elderly patients, patients in renal failure and other subgroups. The patients to be selected are obviously those in whom a high risk of recurrence is predictable. In this sense, the best-known elements of risk associated to the host are advanced age (≥65 years), the need to maintain antibiotic treatment for baseline infection, deficiencies in humoral immunity response, serious underlying diseases and the need to continue taking proton pump inhibitors, among others [185]. As the microorganism is concern, it seems clear that strains with high toxin production, as is the case with many of those grouped as 027, are associated with an increased risk of recurrence [186-189]. Despite all these data, risk scores for predicting recurrences, based on the association of clinical signs or symptoms, have not functioned adequately on most studies [190-196] and only in some works are they attributed a certain orientative value [197, 198]. Some authors have used also toxin production, through what we might consider a surrogate marker, that would be the amplification cycle of PCR curves. Early amplifications before cycle 24 would be associated with worse evolution and very late cycles (amplification cycles beyond 28) would be associated with colonization [6, 199-203].

Interestingly, these scoring systems show us that certain patients in the first episode of CDI have a higher risk of recurrence than other patients in the second episode [185].

Data derived from the Modify I and II studies analyzed by Gerding et al [185] suggest that 75.6% of hospitalized patients meet one or more risk factors for recurrence who would, therefore, be natural candidates to receive bezlotoxumab. In this study, the risks of recurrence are proportional to the risk factors of each patient. With one risk factor the recurrence rate was 31% but with 3 or more risk factors, recurrences reached 46%. In this most-at-risk population, the reduction in recurrent episodes after receiving bezlotoxumab was 53%. However, not all risk factors are equally predictive [193, 194, 198, 204] and none of these models or scores seem to have been widely accepted.

Unfortunately, the latest clinical practice guidelines issued recently by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), although they include 53 therapeutic recommendations, do not provide recommendations or guidance on the use of bezlotoxumab in clinical practice [21].

This working group, thinking of the need for a progressive introduction of this drug in the medical practice of our country and considering economic factors, proposes a score-guidance to decide the use of bezlotoxumab, based on a points-based score, in which risk factors and patient conditions do not receive the same weight. We believe that age >65 years, immunodeficiency, a severe or persistent disease and an amplification cycle of the PCR <24 should be scored with one point each. Diseases or situations such as episodes of CDI in the previous year, malignant underlying diseases, inflammatory bowel disease and liver cirrhosis, should be scored with two points each. Finally, patients with hypertoxigenic or very virulent strains and diseases in which a FMT is indicated and cannot be performed or in which a previous FMT has failed, should receive 3 points with each of these conditions. In our opinion, patients who accumulate 3 or more points are clear candidates to receive bezlotoxumab, but this score has not been validated. Patients with lower scores, in our opinion, should be considered individually. Whenever possible, concomitant antibiotics and acid-suppressing medications, specifically histamine blockers and PPIs, should be removed [205]. The table 1 summarizes this simple, bedside score system, applied to patients with CDI that could help select patients at most risk for CDI recurrence.

Table 1.

Prediction score for recurrent C. difficile Infection

| +1 point: | +2 points: | +3 points: |

|---|---|---|

| >65 years | Previous CDI (previous year) | FMT failure |

| Immunosuppressed | IBD | Indication for FMT but not possible |

| Severe CDI | Malignancy | Hypervirulent strains |

| Antibiotics for other infections | Other high-risk medical conditions | Recurrent episode |

| Toxin B Ct <24 | ||

| Persistent diarrhea >5 days | ||

CDI: Clostridioides difficile infection, IBD: Inflammatory Bowel Disease, FMT: Fecal Material Transplantation.

In conclusion, we believe that in our environment, bezlotoxumab should be administered to patients with an episode of CDI that are at high risk of recurrence. At present, after the recent introduction of the drug in the market, and for economic reasons, it is prudent to select patients with high risk of recurrence and for this we offer a risk score recommendation to select the more clear candidates.

QUESTION 15. Are there additional immunotherapybased options to address CDI?

Immunotherapy consists on using passive immunization with antibody-based products against C. difficile surface proteins to complement the deficient immune response of the host [206]. Targeted antigens are usually toxins A and B (TcdA and TcdB) and the main objective of immunotherapy is usually the prevention of recurrences [206]. As described above, bezlotoxumab is the only antibody-based product approved for clinical use to prevent CDI recurrences to date [181].

Another form of immunotherapy, albeit with no proven efficacy to date, is the use of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG). IVIG have been used to treat the recurrence of CDI with various success rates. Thus far, randomized studies showing a clear benefit are lacking [182]. A prospective analysis with a small number of patients compared the outcomes between use or no use of IVIG. There were no statistical differences in clinical outcomes as measured by all-cause mortality, colectomies, and length of stay [207]. In intravenous formulations for antibody-based products, the latter must be transferred from the systemic circulation to the intestinal lumen. To eliminate this hurdle, oral formulations of IG have also been explored in hamsters [208].

In conclusion, intravenous immunoglobulins are currently not recommended as adjunctive therapy for CDI since there are no conclusive data that demonstrate their efficacy in the prevention of recurrences.

QUESTION 16. What is the current role of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)?

Experience with FMT in refractory or recurrent cases of CDI has accumulated over the years. FMT restores gut microbiota diversity through implantation of donor stools into the gastrointestinal tract of patients with CDI. This treatment has shown good clinical response in adults with refractory or recurrent CDI with few reports of adverse events [209-214].

The FMT technique requires a careful selection of donors to avoid the transmission of any of the known enteric pathogens and potentially of other diseases, that usually leads to the rejection of practically nine out of 10 donor candidates [215]. The reasons for rejection are multiple and include, for example, people who have had tattoos or acupuncture in the last six months or who have travelled to tropical countries in the last half year and those with a body mass index greater than 25 [211]. Today, there is a tendency to rely on repeated donations from a few very well-controlled donors who can supply efficient banks.

Fecal processing is cumbersome and unpleasant, and each donation provides material for approximately two to five transplants. At first, FMTs were performed with fresh material, administered either topically by colonoscopy or by nasoduodenal catheterization, using a minimum of 30 grams of fecal matter. Subsequently, the major milestones to facilitate the process have been to demonstrate that frozen faeces from healthy donors maintain their properties and efficacy and that encapsulated material, either fresh or lyophilized, administered orally in capsules, is as effective as the colonic delivery [26, 216-219].

Liofilization allows preparation and storage for multiple transplants that can be performed almost immediately. This establishes the possibility of creating banks for FMT that permit procedures to be performed quickly after indication. At present, the administration of four capsules of lyophilized material in a single dose is sufficient [34, 217, 220].

Some commercial companies have made available preparations of fecal material or even preparations of intestinal bacterial pools with satisfactory results [221].

In a recent systematic review [222] that included 37 studies (seven randomised controlled trials and 30 case series), FMT was more effective than vancomycin and the overall case resolution was 92%. In cases of initial failure, consecutive courses of FMT resulted in an incremental effect. Recently, however, a tappering cycle of vancomycin was shown, in a comparative study, to be as effective as an FMT [223], however, the authors selected a suboptimal FMT delivery.

There is a general concern regarding long term safety in patients receiving FMT, particularly in relation to metabolic or immune-based disorders [21]. In an open-label, randomized, controlled trial, and in a systematic review that included 273 patients from 11 studies involving more than 10 analyzed cases each, the short-term safety and acceptability of the technique by the patients was high [224, 225]. The transmission of potential pathogens or resistant microorganisms through faeces has been a cause for concern from the outset, but this risk has been minimal to date [226, 227]. Also of concern is the risk of bacterial translocation with distant infections such as bacteremia in immunodeficient patients or in those with increased enteric barrier permeability. It is recommended to avoid FMT in patients with anaphylactic reactions due to food allergies and to be cautious in patients with decompensated cirrhosis or deeply immunocompromised.

Therefore, in the opinion of this working group, the indications for FMT would be focused on patients with proven recurrences and potentially in cases with poor response to treatment, particularly in patients with severe manifestations and who have failed in tappering treatments with vancomycin or fidaxomycin, as long as the procedure is available, the patient accepts it and none of the exclusion criteria for the procedure are met. At the present time, the indication of FMT for first episodes of CDI has yet to be considered an investigational procedure.

In conclusion, FMT is unquestionably one of the most effective ways to avoid the recurrence of CDI and should be offered to patients with multiple recurrences, particularly to those that failed a tappered cycle of oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin. Uncertainties remain about the standardization of the procedure and particularly about its long-term safety. It is also necessary to study the best combination of FMT with other available therapeutic procedures

QUESTION 17. In which situations should surgical intervention be considered?

Patients with severe complicated or fulminant CDI that do not respond to medical treatment in the first 24-48 hours should be evaluated by a surgeon. A classic review showed data supporting total colectomy with end ileostomy as the primary surgical treatment for patients with severe CDI [228]. However, total colectomy is associated with poor outcomes, signficiant morbidity, and a high mortality rate ranging from 35% to 80% [229]. An alternative to a total colectomy procedure, diverting loop ileostomy, combined with colonic lavage, is a less aggressive alternative [229]. Briefly, this technique consists on performing a diverting loop ileostomy and using mechanical lavage to remove bacteria and toxins from the intestinal lumen, followed by a direct instillation of vancomycin into the lumen to further eliminate the remaining CD. This technique has a significantly lower mortality rate when compared with total colectomy and preservation of the colon was achieved in 39 of 42 patients (93%) [229, 230]. In a retrospective multicenter study including data from ten centers of patients who presented with CDI requiring surgery , when comparing colectomy and loop ileostomy, adjusted mortality was significantly lower in the loop ileostomy group [231]. In a more recent metaanalysis, however, it did not appear that diverting loop ileostomy was clearly assoociated with a decrease in mortality but resulted in increased rates of colonic preservation, restoration of intestinal continuity, and laparoscopic surgery[232].

In conclusion, current therapeutical options have reduced the need to resort to surgical invervention, relegating this option to fulminant, non-responding cases. Patients with CDI that do not respond to treatment in the first 24-48hrs should be evaluated by a surgeon; loop ileostomy and colonic lavage should be considered in severe complicated or fulminant CDI without response to medical treatment. Total colectomy should be avoided if at all possible.

QUESTION 18. What is the situation of the vaccines in the near future?

Vaccine candidates based on altered CD toxins A and B are currently under clinical trial study for the prevention of CDI [233, 234]. Early trials suggest that some of these candidates have an acceptable safety and tolerability profile. However, while select candidates have demonstrated substantial immune response in subjects, a definite dose-response relationship has not been established yet and as a result, the ideal dose remains unknown [190]. There is also some concern related to the short durability of the antibody response with some of these candidates, as this would potentially require the administration of additional doses or boosters to provide patients with a longterm clinical benefit [190, 235, 236]. The target population for vaccine administration requires careful consideration, highrisk groups such as subjects with compromised immunity and the elderly might benefit more, however, data on these populations is lacking [190]. The cost of a vaccination regime must also be considered, particularly if targeted to a high-risk population; as high prices might preclude implementation of this strategy in large groups for the prevention of CDI. Results from ongoing trials will be needed to determine whether vaccines constitute a long-term, cost-effective solution to prevent CDI.

In conclusion, vaccine candidates constitute a promising solution to prevent CDI, however, substantial clinical trials are necessary to establish the real benefit associated to their use.

QUESTION 19. Can probiotics be used to prevent recurrences?

There is limited clinical evidence related to the use of probiotics in the treatment of CDI. In a meta-analysis, Saccharomyces boulardii showed promise for the prevention of CDI recurrences [237]. Another meta-analysis suggested that primary intervention of CDI with specific probiotic agents may be achievable [238]. However, a Cochrane review did not find sufficient evidence for the recommendation of probiotics as adjuvant therapy for CDI [239]. Furthermore, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, trial performed to assess the role of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and CDI in older inpatients failed to demonstrate a beneficial effect with probiotics [240]. Even, a recent study shows that the use of probiotics was associated with a higher risk of recurrence [241].

In conclusion, probiotics cannot be recommended for widespread use for the prevention or adjuvant therapy of CDI.

QUESTION 20. How should a patient with a first episode of CDI be managed?

As we previously concluded in question 11, recent literature and guidelines have implicitly agreed that metronidazole should be dismissed as an alternative for the treatment of CDI, even in non-severe cases [21, 162]. In fact, the current approach for treating a first episode of CDI should not be based on the severity of the first episode but instead should be based on the presence or not of risk factors for CDI recurrence (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Treatment of first CDI episodes

*Price-sensitive option in some hospitals

**Remains a research alternative for a first episode.

***In patients at high risk of recurrences antibiotics should be administered in a prolonged tappering way.

With the recent evidence, it seems reasonable and cost-effective to treat a first episode with a low risk for recurrence with vancomycin orally (125 mg four times daily for 10 days) [154, 155]. In a few exceptions, i.e. if the patient has no ability for oral intake, should IV metronidazole be considered.

On the contrary, a first episode with a high risk for recurrence deserves a treatment that has proven to reduce CDI recurrences (i.e. fidaxomicin or bezlotoxumab). Therefore, in our opinion, the current debate consists on trying to identify the patient that, in the presence of a first episode, has a high risk for recurrence and could benefit from new treatment strategies to reduce future recurrences. As we mentioned before, scores for risk factors are needed, and we proposed in question 14 an example of a scoring system for determinig the use of bezlotoxumab in patients at high risk for recurrence (table 1).

Given the demonstrated efficacy of bezlotoxumab in the prevention of recurrent CDI episodes, a regime of oral vancomycin (125 mg four times daily for 10 days) with bezlotoxumab (one dose of 10 mg/kg IV) as adjuvant therapy should be administered for a first episode with a high recurrence risk [183]. A regime of fidaxomicin is also an option in patients with a high risk for recurrence (200 mg twice daily for 10 days), however, it remains a price-sensitive option [160].

Recently, Rubio-Terrés et al. performed a cost-effectiveness analysis in Spain, comparing extended-pulsed fidaxomicin versus vancomycin in patients 60 years and older with CDI. According to their economic model , and the assumptions based on the Spanish National Health Ssystem fidaxomicin is cost-effective compared with vancomycin for the first-line treatment of CDI in patients aged 60 years and older [242].

In MODIFY studies it could not be confirmed that bezlotoxumab reduced the risk of recurrence in patients treated with fidaxomicin, probably because of the small number of patients treated with this drug. Addition of bezlotoxumab to fidaxomicin is another treatment option [183], but it would still be affected by the same cost issues faced by the antibiotic alone and more studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of reducing rCDI with this combination. The use of FMT, in the first episode with high-risk of recurrence, as we mentioned before, is yet only a research alternative. Purportedly, in a setting without economical restrictions, patients at higher risk for recurrence would benefit from fidaxomicin, the best antibiotic option to treat CDI, plus bezlotoxumab, a monoclonal antibody with antitoxin activity.

In conslusion, patients with a first CDI episode and a low risk for recurrence will benefit from oral vancomycin alone. In the case of the presence of high risk factors for recurrence, patients with a first CDI episode will benefit from adding bezlotoxumab or using fidaxomicin.

QUESTION 21. How should a patient with a CDI recurrence be treated?

Ideally, rCDI is a condition to prevent, more than a condition to treat. From a clinical and epidemiological point of view, a recurrence is conventially defined as a CDI episode that re-occurs within eight weeks after complete resolution of the initial or previous episode, confirmed by toxin detection in a stool sample. This definition has been accepted because it is clinically practical and easy to apply; however, patients with previous episodes not considered recurrences because of the time between one episode and the next, should still be managed as patients at high risk for recurrences [194]. The risk of recurrence is variable, ranging between 15% and 25% after the initial episode, reaching rates of up to 60% after a third episode [11, 243, 244].

Treatment options for patients that have recurred are the same as for patients with a first episode with a high risk for recurrence (i.e. fidaxomicin, bezlotoxumab and/or FMT). Recurrence is the highest indicator that a patient needs to be managed focused in preventing recurrences. In these cases, there are different alternatives for treatment that could be applied; i.e. extending or prolonging CDI antibiotic treatment, enhancing the immune system against toxins with bezlotoxumab or microbiota restoration with FMT.

Extending the suppression of CD has been evaluated with strategies that have demonstrated to reduce CDI recurrences. That is the case of vancomycin tapering or fidaxomicin extended treatment. With vancomycin tapering, these regimens typically include a 10to 14-day course of oral vancomycin at a dose of 125 mg four times per day, followed by a tapering dose over two weeks, followed by “pulsed” dosing with 125 mg once every two or three days for two to eight weeks [223, 245] The other alternative, is a regime of extended-pulsed fidaxomicin: 200 mg oral tablets, twice daily on days 1–5, then once daily on alternate days on days 7–25. This strategy has been compared with standard vancomycin, demonstrating superiority of fidaxomicin regarding sustained cure of CDI and lower rates of recurrence [246].

A controlled clinical trial comparing fidaxomicin extended versus a regimen of vancomycin taper would further support these strategies.

Adding bezlotoxumab to the antimicrobial CDI treatment of patients who already have had a recurrence has proven to reduce CDI recurrences [183]. Additionally, it seems reasonable to considerer giving another dose of bezlotoxumab in a patient with a recurrence in which the monoclonal antibody may have been metabolized since the first episode and the cause of CDI persists (i.e. continuous use of antibiotics). However, there is a need for studies that evaluate the efficacy of repeating a bezlotoxumab dose in a patient who has received the monoclonal antibody for a previous episode. This repetition is not approved.

FMT has also demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of recurrences and should be considered in centers where the procedure is standardized [21]. It is currently uncertain how FMT should be linked to other treatment options; i.e. previous preparation with vancomycin or fidaxomicin before the FMT. These are gaps that must be addressed and evaluated in future studies.

Another situation are the patients with multiple recurrences. These patients enter in a loop of recurrences, receiving numerous treatment options for CDI that are not able to stop the recurrence cycle. The main cause of this situation is the persistence of one or more risk factors for CDI recurrence, i.e. continuous antibiotic use for other infections, persistent immunosuppressive therapy, etc. [247]. In these patients the best treatment options that have proven to reduce CDI recurrences should be used. The management of these patients consist of an art between using the current options for treating rCDI and the experience of the physician. The three available ammunitions (fidaxomicin, bezlotoxumab and FMT) must be used in these scenarios. In our opinion, these patients would benefit from the best antibiotic against CD recurrence (fidaxomicin), immunity against CD toxin B (bezlotoxumab) and restoration of the gut microbiota (FMT).

In conclusion treatment options for patients that have recurred are the same as for patients with a first episode with a high risk for recurrence. However, a different management can be applied (i.e vancomycin taper regime or extended pulse of fidaxomicin). In these patients, in our opinion, FMT is the treatment of choice but the association of bezlotoxumab for immunity against toxin B must be considered. Whenever possible, risk factors for CDI recurrence should be halted in order to prevent future recurrences.

QUESTION 22. In patients that have recurrent episodes of CDI induced by new courses of systemic antibiotics, is oral vancomycin prophylaxis effective?

One of the first studies addressing this matter was the retrospective study performed by Carignan et al. in 2016 [248] in which they studied 551 CDI episodes and observed that oral vancomycin prophylaxis decreased the risk of further recurrence in patients who had a former rCDI episode (AHR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.32–0.69; P <0.0001)[248]. This reduction was not observed for primary CDI episodes.

More recently, in 2019, two new studies have been published. Knight et al. evaluated retrospectively the long-term efficacy of oral vancomycin prophylaxis in preventing CDI recurrence in subjects who require subsequent antibiotic exposure. They observed that CDI recurrence within 12 months was significantly lower in subjects receiving oral vancomycin prophylaxis compared to those who did not receive it (6.3% vs 28.8%; odds ratio (OR): 0.16; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.04-0.77; P =0 .011)[249]. Zhang et al. presented a small series of patients in which they observed that prolonged vancomycin prophylaxis at a dose of 125 mg orally daily was an effective and well-tolerated option for secondary prevention of rCDI [250].

Several recent communications have been made at the Infectious Diseases Week meeting, held in Washington (ID Week) in October 2019, providing more evidence on this matter. Two retrospective studies [251, 252] including 72 and 264 patients, respectively, evaluated the use of prophylaxis with oral vancomycin, 125 mg twice daily in patients with a history of CDI and observed that the incidence of CDI was significantly lower in the group receiving oral prophylaxis compared to the control group.

A randomized, prospective study was presented by Johnson et al., in which 100 patients were enrolled 1:1 to either oral vancomycin (dosed at 125 mg once daily while receiving systemic antibiotics and continued for 5 days post completion of systemic antibiotics), or no prophylaxis. No cases of rCDI were diagnosed in the prophylaxis group compared to 6 (12%) in the no prophylaxis group (p = 0.03) [253]. As can be noted, there is still limited data regarding this issue, and more randomized controlled trials are needed. However, the existing literature holds promise for the use of oral vancomycin prophylaxis when a subsequent antimicrobial therapy is planned in a high-risk of rCDI patient.

In conclusion, antibiotic prophylaxis cannot be recommended for widespread use for the prevention of rCDI, however in selected cases that fulfill a high risk profile for rCDI and are scheduled to receive systemic antimicrobials, it can be indicated.

SUMMARY

1. CDI should be suspected in all diarrheic episodes of patients of any age, with or without traditional risk factors for CDI. except for those younger than 2 years.

2. One stool specimen is the best cost-effective number needed for the diagnosis of CDI.

3. Both, samples without any transport medium and samples with transport medium for aerobic enteropathogens, as Cary-Blair, are suitable for the diagnosis of CDI.

4. Microbiologists in the laboratory can have an important role in the improvement of the CDI diagnosis by processing unformed stool specimens from patients older than 2 years, independently of the request by the clinicians.

5. Rectal specimens are useful for CDI diagnosis in patients whose stool specimens cannot be obtained. Stool specimens are more sensitive than colonic biopsies for the diagnosis of CDI.

6. Detection of GDH by EIA as screening test, followed by a rapid confirmatory technique as a NAAT alone or together with a toxin A and B EIA, and the use of toxigenic culture, is the optimal diagnostic combination of laboratory tests to diagnose CDI.

7. Tests of antibiotic susceptibility should be performed annually to detect the emergence of resistance in reference laboratories or in specific situations but not in a daily regular basis.

8. Detection of toxigenic C. difficile from stool specimens is not adequate as a follow-up method for the evolution of patients with CDI.

9. Rapid laboratory work-up and reporting of tests for toxigenic C. difficile is crucial for the control and management of this illness.

10. The basic support approach for patients with CDI includes: fluids and electrolyte replacement, and removal of intestinal peristalsis inhibitors, antacid medication, and concomitant antibiotics, when feasible.

11. Oral vancomycin is the recommended drug for an initial CDI episode; oral fidaxomicin or bezlotoxumab, should be considered in initial CDI episodes with a high risk of recurrence. Metronidazole should be restricted to situations in which vancomycin or fidaxomicin are contraindicated or an oral administration is not possible.

12. Rifaximin, nitazoxamide, fusidic acid, tygecicline, and teicoplanin are currently not considered as therapy options for CDI. Ridinilazole is a promising antibiotic with phase 3 clinical trials set to start in 2019 to demonstrate non-inferiority over vancomycin for the treatment of CDI.

13. Bezlotoxumab is the first approved treatment for the prevention of CDI recurrence, with a demonstrated higher efficacy in all sub-groups of patients at greater risk for recurrence.

14. Bezlotoxumab should be administered to patients with episodes of CDI that are at high risk of recurrence. We suggest that, despite limitations, risk scores should be used to optimize candidate selection.

15. Given the lack of conclusive data, intravenous immunoglobulins are currently not recommended as adjunctive therapy.

16. FMT should be offered to patients with multiple recurrences, particularly to those who failed a tapered cycle of oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin. Uncertainties remain about the standardization of the procedure and particularly about its long-term safety.

17. Surgery should be considered in those patients with CDI that do not respond to treatment in the first 24-48hrs; loop ileostomy and colonic lavage should be considered in severe complicated or fulminant CDI without response to medical treatment.

18. Vaccines constitute a promising solution to prevent CDI, however, substantial clinical trials are necessary to establish the real benefit associated to their use.

19. Probiotics cannot be recommended for the prevention or adjuvant therapy of CDI.