Abstract

Vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (V-ATPase)-driven proton pumping and organellar acidification is essential for vesicular trafficking along both the exocytotic and endocytotic pathways of eukaryotic cells. Deficient function of V-ATPase and defects of vesicular acidification have been recently recognized as important mechanisms in a variety of human diseases and are emerging as potential therapeutic targets. In the past few years, significant progress has been made in our understanding of function, regulation, and the cell biological role of V-ATPase. Here, we will review these studies with emphasis on novel direct roles of V-ATPase in the regulation of vesicular trafficking events.

Introduction

Vesicular trafficking is an essential cellular process in eukaryotic cells to deliver either membrane proteins or soluble cargos from one compartment to another. Defects of trafficking have been recently recognized as an important cell biological mechanism in various human diseases such as cancer, neurological disorders, and autoimmune and metabolic diseases including diabetes [1]. Both exocytotic and endocytotic traffic should be regulated by the different forms of ‘protons’ including transmembrane pH gradient, membrane potential and the acidic pH lumen of their intracellular organelles. The acidic environments outside the cells are also important for mammals, examples being osteoclast bone resorption lacuna, and the extracellular compartment of tumors as well as renal tubular and epididymal lumens. V-ATPase is a major proton pump in the proton homeostasis of eukaryotic cells. In accordance with their crucial roles in cellular function, V-ATPases have been also implicated in the pathophysiology of various human diseases [2, 3••].

Most of the biochemistry, cell biology, and physiology related to V-ATPase have been recently reviewed [2, 3••, 4, 5, 6]. Generally accepted roles of V-ATPase include establishing acidic pH, which gives optimal conditions for enzymes in the lumens of compartments such as lysosomes and bone resorption lacuna. Acidic pH is also necessary for the entry of viruses, bacteria and dissociation of internalized ligand–receptor complexes in endosomes. The electrochemical proton gradient constitutes a driving force for the accumulation of neurotransmitters and hormones into secretory vesicles. However, recent studies revealed that, in addition to well-known functions of V-ATPase, its subunits may have direct roles in the regulation of vesicular trafficking.

In this review, we will focus on targeting V-ATPase to the membranes of specific intracellular compartments. We will also discuss the roles of V-ATPase in vesicular trafficking between organelle and plasma membranes in the exocytotic pathway. Finally, we will discuss the emerging role of V-ATPase in interaction with small GTPases, well-known ‘molecular switches’, and the implication of this rendezvous for the regulation of the endocytotic pathway.

The V-ATPase: structure and function of the proton pumping rotary nano-motor

Structure and function of V-ATPase

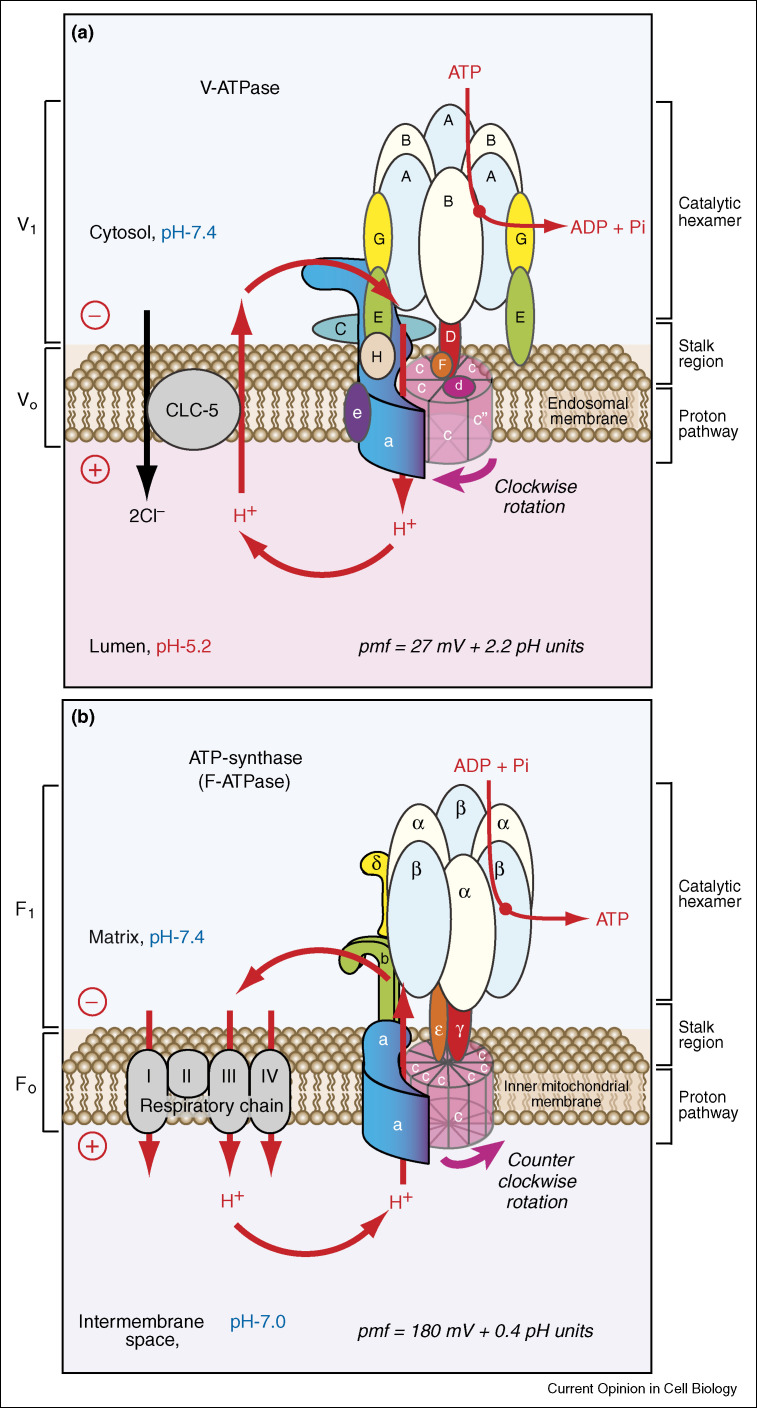

The V-ATPase is a multimeric complex that functions as a proton pumping rotary nano-motor (Figure 1a). Both yeast and mammalian V-ATPases share a high degree of homology in their subunit compositions [7] and similarities in biochemical mechanism [3••, 4, 5]. The cytoplasmic V1-sector is composed of eight different subunits with defined stoichiometry (A3B3CDEFG2H1-2) and is responsible for ATP hydrolysis. The transmembrane VO-sector is composed of six different subunits (ac4c′c″de) and is responsible for proton translocation. Functionally, the catalytic hexamer A3B3 is connected to the proton pathway by stalks. The central stalk (formed by subunits D and F) is attached to a ring of hydrophobic subunits (c, c,′ c″) and operates as a ‘rotor’ (Figure 1a, in red). The cytosolic N-terminal domain of the a-subunit together with the C, E, G, and H subunits form two peripheral stalks. They are attached to the A3B3 hexamer and form a ‘stator’. Thus, ATP hydrolysis and proton pumping are coupled by a rotary mechanism, that is, rotation of a ‘rotor’ relative to a ‘stator’ in the nano-machine.

Figure 1.

Comparative structural models and functional roles of V-ATPase and ATP-synthase (F-ATPase) expressed in endomembrane organelles and mitochondria, respectively. The comparative subunit composition of transmembrane (VO and FO) and peripheral (V1 and F1) sectors are indicated on the left, while the catalytic hexamers, stalks and proton pathways are indicated on the right. Homologous subunits, such as the A-subunit of V-ATPase and the β-subunit of F-ATPase are shown in the same colors. (a) V-ATPase is shown as a primary proton pumping nano-motor. ATP hydrolysis drives clockwise rotation of the central stalk and ring of proteolipid subunits indicated in red. This rotation leads to the translocation of protons from the cytosol to form an acidic lumen of endomembrane organelles, and generates an electrochemical proton gradient or proton-motive force (pmf) across the membrane. In endosomes the V-ATPase promotes the neutralizing current mediated by electrogenic CLC-5 (nCl−/H+-exchanger with unknown stoichiometry, which might be n = 2 as in its bacterial homologue [45]) and drives further acidification. The values of pmf components ΔΨ and ΔpH were recently determined for the early phagosomal compartment [46••]. (b) Mitochondrial ATP-synthase (also called F-ATPase) is shown as a secondary pump. F-ATPase function (proton translocation, counter clockwise rotation, and coupled ATP synthesis) is driven by pmf that is primarily generated during the function of respiratory chain enzymes. The function and rotation of both V-ATPase and F-ATPase are reversible under certain experimental conditions. The rotation of yeast V-ATPase (see Supplementary Information, Figure S1 and Movie S1) [11•] and bacterial F-ATPase (see Supplementary Information, Figure S2 and Movie S2) [10•] nano-motors. Movies are adapted from Refs. [10•, 11•].

Similarities and differences between V-ATPase and F-ATPase

V-ATPase shares similarities with ATP-synthase (F-ATPase) in subunit structure and rotational catalysis, as schematically shown in Figure 1b. Homologous subunits, such as the A-subunit of V-ATPase and the β-subunit of F-ATPase are shown in the same color. Both models (Figure 1a,b) are consistent with experiments showing subunit rotation in bacterial F-ATPase [5, 8, 9••, 10•] and yeast V-ATPase [5, 11•] (see Supplementary Information, Figures S1, S2 and Movies S1, S2). In spite of their similarities, there are important differences between F-ATPase and V-ATPase. F-ATPase is exclusively localized to the mitochondrial inner membrane, where it operates predominantly as an ATP-synthase, coupled with the proton motive force (pmf) generated by the respiratory chain (Figure 1b). By contrast, V-ATPases are found in diverse endomembrane organelles and plasma membranes (Figure 2 ), and function as proton pumps (Figure 1a). The targeting, function and regulation of V-ATPase is more complex than F-ATPase and depend on the specificity of cell biological function as well as membrane composition and cytosolic environment of these compartments.

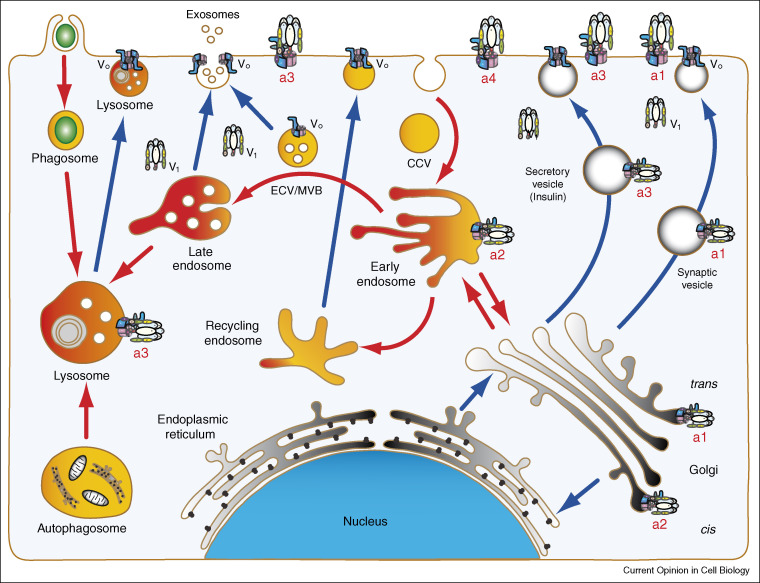

Figure 2.

Differential targeting of the a-isoforms and vesicular trafficking of V-ATPase in eukaryotic cells. The scheme depicts the compartments of endocytotic (yellow/red) and exocytotic (gray) pathways. Vesicular trafficking steps are indicated for endocytosis in red arrows and for exocytosis in blue arrows. Differential targeting of V-ATPase is cell-specific and compartment-specific. Localization of V-ATPase a-isoforms is shown as demonstrated in Figure 4 and described in text. (i) In particular, V-ATPase with a1-isoform is targeted to Golgi and involved in synaptic vesicles fusion and secretion. It is also found on presynaptic plasma membrane. (ii) V-ATPase with a2-isoform is targeted either to early endosomes or to Golgi. In early endosomes a2-isoform functions as pH-sensor by recruiting small GTPases in acidification dependent manner and involved in the formation of endosomal carrier vesicles also known as multivesicular bodies (ECV/MVB). These vesicular intermediates are involved in the trafficking between early and late endosomes or in exosomes formation and secretion. (iii) V-ATPase with a3-isoform is targeted to lysosomes and in some cells is involved in lysosomal secretion and is also localized to plasma membrane. (iv) V-ATPase with a4-isoform is specifically targeted to plasma membrane of some cells.

Diverse V-ATPases targeting to unique acidic compartments

Multiple subunit isoforms of V-ATPase

Consistent with the presence of V-ATPases in diverse compartments [12, 13], a large spectrum of subunit isoforms are found in mammals; two isoforms for the B, E, H and d subunits [14, 15, 16, 17, 18] and three isoforms for the C and G subunits [15, 18, 19, 20]. The expression of these isoforms is tissue-specific and cell-specific. The B subunit isoform B1 is specific for kidney and inner ear, whereas B2 is ubiquitous. Thus, the mutations of B1 are not lethal, but cause human renal acidosis with hearing defects [14]. V-ATPase with C1 is found ubiquitously, whereas C2-a is found specifically in the lamellar bodies of lung alveolar epithelial cells responsible for surfactant secretion and C2-b is found in plasma membranes of renal α-intercalated and β-intercalated cells responsible for ion homeostasis [18, 19]. V-ATPase with the E1 isoform is located specifically in developing acrosomes of spermatids and acrosomes in mature sperm, whereas E2 is expressed in all tissues that have been examined [17]. The G subunit isoform, G1 is expressed ubiquitously, whereas G2 and G3 are found in neuron synaptic vesicles and kidney, respectively [20]. Recent immunoprecipitation experiments have demonstrated that V-ATPases with unique combinations of subunit isoforms are localized in specific cellular membranes that could dictate their functions [18, 21].

Role of a-subunit isoforms in intracellular targeting of V-ATPase

Mammalian transmembrane VO of V-ATPase is more complicated than Fo of F-ATPase (Figure 1a,b). It is formed by a transmembrane ring and an adjacent a-subunit, containing a large N-terminal cytosolic tail and a C-terminal hydrophobic domain with six to nine putative membrane spanning helices [3••, 4]. The interface between the a-subunit and the ring is a target for bafilomycin A1 and concanamycin, macrolide antibiotics, which specifically inhibit V-ATPase catalysis and rotation. Their high specificities have contributed to the study of organelles with acidic luminal pH.

Multiple isoforms with unique intracellular localizations are also found for the a-subunit. In yeast the N-terminal cytosolic domains of two a-subunit isoforms (Vph1p and Stv1p) are responsible for the specific targeting of V-ATPase to vacuolar and Golgi compartments, respectively [22•]. By contrast, the C-terminal domain has been implicated in the specific targeting of 17 a-subunit isoforms recently identified in Paramecium tetraurelia [23•].

Four a-subunit isoforms (a1, a2, a3, and a4) were found in mice and humans [24, 25, 26, 27]. They are localized in different endomembrane organelles and plasma membranes of specialized cells (Figure 2). The targeting of V-ATPases with different a-isoforms is a cell-specific dynamic process. During osteoclast differentiation, the a3-isoform relocates from lysosomes to the plasma membrane (Figure 3a,b) [28••]. It is noteworthy that this isoform is specifically (about 80%) targeted to insulin containing secretory granules in pancreatic β-cells (Figure 4a–d) [29•].

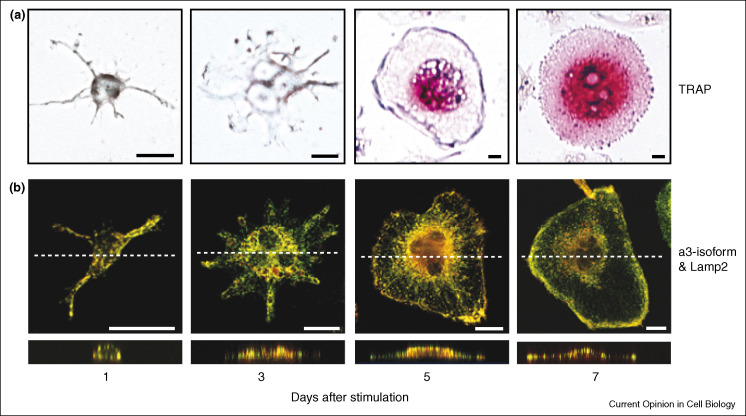

Figure 3.

Differential targeting of the a3-isoform of V-ATPase in osteoclasts. (a) Raw 264.7 cells were cultured for 7 days in medium containing sRANKL and M-CSF. Osteoclast-like cells were identified as multinuclear cells exhibiting positive staining for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP). (b) Targeting and colocalization of a3 and Lamp2 in lysosomes of RAW 264.7 cells and their targeting to the plasma membrane during differentiation into osteoclast-like cells. Double immunochemical staining with anti-a3 and anti-Lamp2 antibodies was performed after different days of osteoclast differentiation followed by confocal microscopy analysis. Merged images are shown both in horizontal view (x–y sections, upper panels) and lateral view (z–x sections, lower panels). Adapted from Ref. [28••].

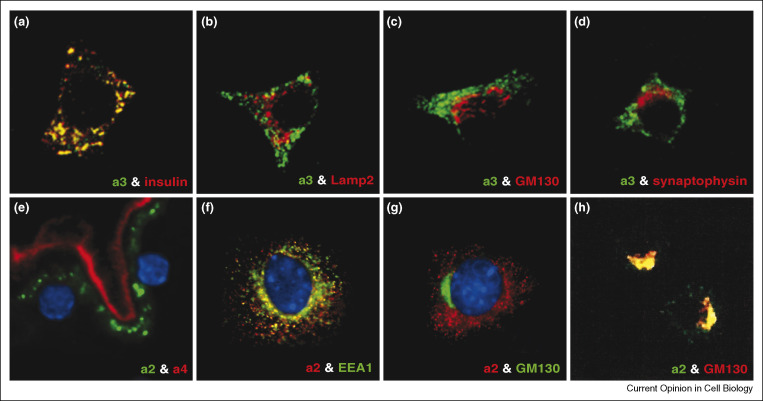

Figure 4.

Differential targeting of the a2-isoform, a3-isoform and a4-isoform of V-ATPase in eukaryotic cells. (a–d) Specific targeting and localization of the a3-isoform to insulin containing secretory granules in pancreatic β-cells. βTC6 cells were double stained with antibodies against the a3-isoform (green) and against either (a) insulin, (b) Lamp2, (c) GM130 or (d) synaptophysin (red) as indicated. Adapted from Ref. [29•]. (e) Differential targeting of a2-isoform to endosomes and a4-isoform to plasma membrane in kidney proximal tubule epithelial cells. Mouse kidney proximal tubules were double stained with antibodies against the a2-isoform (green) and against the a4-isoform (red). (f, g) Specific targeting of the a2-isoform to early endosomes in mouse proximal tubule cells (MTC). Cells were double stained with antibodies against the a2-isoform (red) and against either (f) EEA1 or (g) GM130 (green) as indicated. Adapted from reference [30••]. (h) Localization of the a2-isoform to Golgi complex in osteoclasts. Raw 264.7 cells were double stained with antibodies against the a2-isoform (green) and against the GM130 (red). Adapted from Ref. [28••].

Targeting and localization of a-isoforms are also compartment-specific. All four isoforms are expressed in mouse kidney proximal tubule cells, however, while a1-isoform, a3-isoform, and a4-isoform are targeted to the plasma membrane, the a2-isoform is targeted to early endosomes in situ (Figure 2) [30••]. Specific localization of a4 to the plasma membrane and a2 to early endosomes in proximal tubule cells is shown (Figure 4e,f) (see Supplementary Information, Figure S3 and Movie S3). It is noteworthy that in these cells a2-isoform does not target to Golgi (Figure 4g). By contrast, both a2-isoform and a1-isoform are targeted to the Golgi complex in cultured osteoclast cells (Figure 4h) [28••]. Interestingly, recent studies suggested that the a2-isoform is involved in Golgi function and development of congenital disorders of glycosylation in humans [31••]. The kidney specific a4-isoform is also specifically targeted to the apical plasma membrane of collecting duct intercalated and epididymal clear cells [32]. In nerve terminals, the a1-isoform is specifically delivered to synaptic vesicles from which it could also be relocated to the presynaptic plasma membrane [33]. Although it is generally accepted that a-subunit isoforms are crucial for trafficking V-ATPase, the mechanism of their specific targeting is currently unknown in mammalian cells.

Regulation of V-ATPase and the luminal pH of organelles

Diverse acidic organelles are present in eukaryotic cells with different lumenal pH. The pH of compartments becomes more acidic as the exocytotic or endocytotic pathways approach their destination. The regulation of luminal acidity is selectively achieved by the combination of first, ‘fine-tune’ regulation of V-ATPase activity depending on isoform composition and cellular micro-environments (cytosolic and luminal environment, membrane composition, etc.) and second, specific targeting and trafficking of V-ATPase as well as other ‘acidification machinery’ proteins such as channels, exchangers to organelles.

Regulation of V-ATPase by reversible assembly/disassembly of V1VO sectors

Reversible assembly/disassembly of VO and V1 sectors is an important regulatory mechanism of V-ATPase, and observed in response to glucose depletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [34] and kidney proximal tubule epithelial cells [35••, 36, 37] as well as in response to ceased feeding in Manduca sexta [6]. In yeast, this mechanism is regulated by a-isoforms of V-ATPase and dependent on the cellular and membrane environment where the two isoforms are located [3••, 38, 39•, 40]. V-ATPase (with Vph1p a-subunit) targeted to vacuoles is disassembled upon glucose depletion, whereas that (with Stv1p a-subunit) targeted to the Golgi does not [38]. However, V-ATPase with a chimeric a-subunit of Vph1p and Stv1p (N-terminal and C-terminal, respectively) and localized in vacuoles is disassembled. These results suggest that the N-terminal cytosolic tail of a-subunits function as a glucose sensor [3••] and its function also depends upon the cytosolic, lumenal and/or membrane environment where V-ATPase is localized [40]. The glucose-dependent assembly/disassembly of V-ATPase is partly controlled by vacuolar luminal pH [39•]; however, this is not the only cellular parameter involved [40]. The disassembly (but not assembly) involves the cytosolic microtubular network [3••], whereas the assembly (but not disassembly) requires the cytosolic RAVE (regulator of H+-ATPase of vacuolar and endosomal membranes) complex [34].

In mammalian renal epithelial cells, the effect of glucose on V-ATPase is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent signaling [36]. The direct interaction of cytosolic aldolase (an enzyme in the glycolytic pathway) with a, B and E subunits has been also implicated in reversible assembly/disassembly of V-ATPase, and aldolase was suggested to be a glucose-sensor [35••]. Importantly, the crucial role of this regulatory mechanism for the endocytotic protein degradation pathway was recently demonstrated in mammalian dendritic cells [41••]. The regulation of V-ATPase activity by the assembly of VOV1 sectors onto the lysosomal membrane was observed during maturation of these cells. This mechanism is crucial for lysosomal acidification, activation of proteases, protein degradation and antigen presentation [41••].

Regulation of V-ATPase coupling efficiency by specific subunit isoforms

Modulation of coupling efficiency between ATP hydrolysis and proton pumping is also important regulatory mechanism of V-ATPase. The a-subunit isoforms and non-homologous 90 amino acid region unique to the A-subunit V-ATPase not found in F-ATPase have been implicated in regulating in yeast [38, 39•]. However, the unique properties of mammalian V-ATPases with different isoforms are difficult to analyze because heterogeneous assemblies are present in the same cell. Thus ‘mouse/yeast’ hybrid V-ATPase, constructed by introducing mouse cDNA into mutant yeast lacking the corresponding gene, may shed light on the properties and function of subunit isoforms. This approach was successfully applied to study the roles of the mouse E-subunit and C-subunit isoforms in the regulation of V-ATPase coupling efficiency [17, 19].

Modulation of organelle pH by vesicular trafficking and chemiosmotic mechanisms

Targeting and vesicular trafficking of V-ATPase to specific membranes is an important regulatory mechanism for acidification. In renal intercalated and epididymal clear cells, the density of V-ATPase in the plasma membrane is controlled by a balance of endocytosis and exocytosis of apical vesicles containing the same enzyme [42, 43]. The V-ATPase generates an electrochemical proton gradient or proton-motive force consisting of membrane potential (ΔΨ) and proton gradient (ΔpH). In endosomes, they promote electrophoretic chloride transport via the CLC5 exchanger (2Cl−/H+-antiporter) increasing the acidity of the compartment (Figure 1a) [44, 45]. The values of ΔΨ 27 mV and ΔpH 2.2 units were recently determined in direct FRET experiments in early phagosomes where the lumenal pH is 5.2 [46••]. Chloride accumulation during endosomal acidification (with a lumen pH of 5.3–5.6) was also shown in vivo [47]. The emerging roles of the CLC-family of chloride transporters in the endosomal/lysosomal pathway [44, 45] as well as important roles of the NHE-family of cation/proton exchangers in organellar acidification and homeostasis were recently discussed [48].

V-ATPase and acidic organelles are essential from yeast to mammals: functional role of acidic pH

Yeast mutants lacking any gene encoding a V-ATPase subunit cannot grow at neutral pH (VMA phenotype). Silencing in Caenorhabditis elegans of three of the four a-subunit isoforms results in death during development [49]. Deletion of the mouse c-subunit, that is coded by a single gene, results in impaired acidification and causes defective intracellular trafficking essential for development [50]. These data indicate that V-ATPase is required for vesicular trafficking during early development from worms to mammals. The crucial role of V-ATPase in establishing acidic compartments is generally accepted [2, 3••, 4, 5, 12, 51, 52•, 53]; however, emerging evidence indicates that various subunits of V-ATPase may also have direct roles in the regulation of vesicular trafficking within both the exocytotic and endocytotic pathways.

Direct role of V-ATPase in vesicular trafficking of exocytotic pathway

Roles of V-ATPase in membrane fusion

Vesicular trafficking, essential for communication between organelles, involves a combination of two crucial steps: first, budding of vesicles from a donor and second, fusion with an acceptor compartment/membrane [54]. These two steps are tightly regulated to ensure efficient formation of vesicles during budding and to avoid mis-targeting of their cargo during the fusion step. Recent emerging evidence indicates that providing an acidic environment is not the exclusive function of V-ATPase, and that it is directly involved in both budding and fusion events.

Direct participation of VO sector c-subunits in membrane fusion has been proposed for yeast vacuole biogenesis. According to this model, the c-subunits of VO are directly involved in the fusion of two vacuoles (VO trans-complex formation) which also depends on Rab-GTPase Ypt7 and calmodulin [55••]. Inactivation of the Vph1p a-subunit also blocks fusion between VO sectors [56, 57]. It is noteworthy that in contrast to fusion, vacuole fission and fragmentation in vivo depends on proton pumping by V-ATPase [57]. Although the exact molecular mechanism of VO trans-complex formation remains controversial, recent studies suggest a direct role of V-ATPase in fusion in other organisms (Figure 2). In Drosophila melanogaster, the VO a-subunit has been implicated in synaptic vesicle fusion [58] and the a1-isoform directly interacts with calmodulin at fly synapses [59]. In Caenorhabditis elegans, the a-subunit mediates secretion of Hedgehog-related proteins from exosomes to the apical membrane [60]. Finally, crystallographic studies of the c-ring of Nephrops norvegicus V-ATPase also suggest the direct role of the VO-sector in membrane fusion [61].

Role of V-ATPase in mammalian hormone exocytosis

In mouse pancreatic β-cells, the V-ATPase containing the a3-isoform is specifically targeted to insulin-containing secretory vesicles (Figure 4a–d) [29•]. Oc/oc-mice, containing a null mutant of the a3 gene, are unable to secrete insulin in response to glucose or depolarization, suggesting that they are defective in insulin exocytosis. Increased levels of the a2-isoform in oc/oc-mice did not replace the function of the a3-isoform. However, while the inhibition of V-ATPase by bafilomycin results in disappearance of endomembrane acidic lumens it does not prevent secretion of insulin in βTC9 cell line. These results suggest that insulin secretion does not require proton pumping, but intact V-ATPase with a3-isoform is necessary. The a3-isoform is highly expressed in endocrine tissues including adrenal, parathyroid, thyroid and pituitary glands, suggesting that function of the a3-isoform could be commonly involved in the regulation of the exocytotic pathway and secretion (Figure 2) [62].

Trafficking of V-ATPase to the plasma membrane: secretory lysosome of the osteoclast

Bone homeostasis in vertebrates depends on bone formation by osteoblasts and resorption by osteoclasts. During the resorption process, V-ATPase secrets protons into ‘bone resorption lacuna’, a compartment formed between the plasma membrane and the bone surface. This compartment is rich with proteases and an acidic lumen is essential for mineral dissolution and matrix protein degradation. The a3-isoform of V-ATPase is specifically localized to the plasma membrane of osteoclasts [24]. Consistent with these findings, mutations in the a3-isoform result in deficient bone resorption and osteopetrosis in humans [63, 64] and mice [65].

The RAW264.7 cell is an established macrophage line that can form osteoclast-like cells upon differentiation. The a3-isoform is localized in lysosomes before stimulation, whereas after stimulation the same isoform is targeted to the plasma membrane together with lysosomal enzymes, suggesting that lysosome exocytosis forms osteoclast plasma membranes (Figure 3) [28••]. Thus, localization of the V-ATPase a3-isoform is a dynamic membrane process. In human osteoclasts the a3-subunit is colocalized with the VO d2-isoform [66]. Knockout of d2-isoform in mice results in markedly increased bone mass because of defective osteoclasts and enhanced bone formation [67••]. However, the disruption of the d2-gene did not affect osteoclast differentiation or V-ATPase activity, suggesting the direct role of the d2-isoform in the fusion of osteoclast progenitors. Exocytosis of lysosomes is an important function in phagocyte-derived, neutrophil-derived, and monocyte-derived cells including macrophages and osteoclasts. Thus, the fusogenic role of V-ATPase could play an important biological role in general.

Direct role of V-ATPase in vesicular trafficking of endocytotic pathway

Role of V-ATPase in endocytosis of viruses, microorganisms, and toxic molecules

The endocytotic pathway is used by viruses and bacteria to enter into eukaryotic cells. They have developed a variety of strategies in order to reach their site of replication (cytosol or intracellular organelles) and/or to avoid degradation in lysosomes [68, 69]. One strategy of the infection process requires a V-ATPase-driven acidic environment in early or late endosomes. For example, membrane fusion of vesicular stomatitis virus and its escape to the cytosol depends upon the endosomal acidic lumen. The function of the M2-protein from influenza A-virus and SARS coronavirus proteinase also need acidification. The translocation of various toxins from endosomes to the cytosol also depends upon acidification and includes among others: anthrax, diphtheria, and clostridial toxins [68, 70, 71]. An alternative survival strategy is applied by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. These microorganisms diminish the acidity of phagosomes and impair their fusion with lysosomes [69].

An acidification-independent strategy of internalization is employed by HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and requires the direct interaction with V-ATPase. Negative factor (Nef) of HIV plays a crucial role in viral pathogenesis and promotes the progression to AIDS. Nef directly interacts with the H-subunit of V-ATPase and promotes CD4 internalization at the plasma membrane [72]. The H-subunit is homologous to β-adaptins [73], interacts with the μ2-chain of AP2 adaptor and promotes clathrin-coated vesicle (CCV) formation [74], suggesting that V-ATPase is acting as a scaffolding complex. Thus this strategy of viral infection involves direct interaction with V-ATPase in the early stages of budding and coat formation at the plasma membrane.

When V-ATPase meets with small GTPases: functional significance of this rendezvous

Organelles along the endocytotic pathway have acidic lumenal pH that is crucial for vesicular trafficking. Acidification in early endosomes of BHK cells is required for the formation of endosomal carrier vesicles (ECV) or multivesicular bodies (MVB) (Figure 2), that mediate either trafficking between early and late endosomes [75] or involved in exosomes formation and secretion [76••]. It has been proposed that biogenesis of ECV/MVB vesicles is a tightly regulated budding process coupled to the acidification of endosomes. Indeed, it has been shown the acidification-dependent recruitment of cytosolic coatomer proteins (β-COP, ɛ-COP) and Arf1 small GTPase onto early endosomes. Furthermore, the involvement of a hypothetical pH-sensing protein (PSP) in direct interaction with β-COP during the formation of endosomal carrier vesicles has been suggested [77, 78].

In kidney physiology, receptor-mediated endocytosis by proximal tubule epithelial cells plays an important role in protein homeostasis via reabsorption of albumin, hormones, chemokines, vitamin-binding proteins, etc. [53]. This protein degradation pathway also depends on endosomal acidification, with defects in this process leading to proximal tubulopathies in humans and mice [53]. Early studies on small GTPases demonstrated the colocalization of V-ATPase with Arf6 and ADP-ribosylation factor nucleotide site opener (ARNO) in early endosomes of the degradation pathway [79]. The recruitment of these small GTPases was driven by intra-endosomal acidic pH, and the presence of PSP in the endosomes was proposed [80]. Recently, V-ATPase has been identified as pH-sensor that directly interacts with small GTPases in an acidification-dependent manner [30••, 81, 82]. In particular, the a2-isoform is targeted to early endosomes of the proximal tubule (Figure 2) (Figure 4e,f) (see Supplementary Information, Figure S3 and Movie S3) and directly interacts with ARNO in acidification-dependent manner, while Arf6 specifically interacts with the c-subunit of the VO-sector of V-ATPase. Importantly, these studies also demonstrated that the acidification-dependent interaction between V-ATPase and small GTPases is crucial for protein trafficking between early and late endosomes [30••] (see Supplementary Information, Figure S4 and Movies S4,S5). Although these studies showed that V-ATPase could modulate vesicular trafficking by scaffolding and recruiting small GTPases, the downstream targets of this V-ATPase/ARNO/Arf6 complex as well as functional significance of this rendezvous remains to be elucidated.

The Ras-superfamily of small GTPases function as ‘molecular switches’ and regulate an extraordinary variety of cell functions [83]. The transition between the ‘on’ and ‘off’ states of this molecular device is mediated by the GDP/GTP cycle. The ADP-ribosylation factor (Arf) family belongs to the Ras-superfamily and also functions as a molecular switch to regulate vesicular traffic and organelle structure [84]. The activation of Arfs (GTP-bound conformation, ‘on’-state) is mediated by guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), while deactivation (GDP-bound conformation, ‘off’-state) is catalyzed by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). Both small GTPase Arf6 and its cognate GEFs and GAPs have been implicated in the regulation of the endocytotic pathway and organelle biogenesis by: first, recruiting coat components; second, modifying phospholipids; and third, remodeling the cytoskeleton near vesicular membranes [30••, 85••]. Thus, the acidification-dependent recruitment of ARNO/Arf6 and their binding to endosomal V-ATPase may trigger these downstream pathways giving rise to the endosome carrier vesicles (ECV/MVB) formation.

Finding the interaction between V-ATPase and small GTPases pointed out the intriguing possibility that small GTPases might function as ‘molecular on/off switches’ for V-ATPase function. The following results suggest possible ‘cross-talk’ between V-ATPase/small GTPase interaction and disassembly/assembly of V-ATPase. First, the glucose-dependent disassembly of V-ATPase is also controlled by the acidification of vacuoles suggesting the presence of a vacuolar pH-sensor [3••, 39•, 40]. Second, V-ATPase is known to directly interact with the actin-microfilament cytoskeleton [3••, 6, 86] and requires an intact microtubular network for the dissociation of VOV1 complex [3••]. Thus, when recruited to V-ATPase, Arf6 could be involved in cytoskeleton remodeling [3••, 6, 85••, 87]. Third, binding of V-ATPase to F-actin [86] and glucose-dependent assembly of the VOV1 complex [36] depend on PI3-kinase activity, that is also necessary for specific recruitment of ARNO [88] and Arf6-mediated actin dynamics [89]. Finally, aldolase modulates assembly/disassembly of V-ATPase by the interaction with the a, B, and E subunits [35••, 36, 37]. Recently, the direct and specific interaction of aldolase with ARNO has been demonstrated (Marshansky Laboratory, unpublished data) suggesting that ARNO can modulate the assembly/disassembly of the V-ATPase/aldolase complex. On the basis of these data it is tempting to propose that the pH-sensing function of V-ATPase and the acidification-dependent recruitment of small GTPases are integral parts of the glucose/aldolase-dependent regulation of V-ATPase. Thus, the generally accepted function of small GTPases as ‘molecular switches’ may directly be applied to the assembly/disassembly of V-ATPase and turning ‘on/off’ this remarkable nano-machine.

Conclusions and perspectives

The function of V-ATPases in different compartments is tightly coordinated with the unique roles of different organelles and their cytosolic microenvironments. Identification of the mechanisms of isoform-specific targeting and assembly of V-ATPase at specific organelles in mammalian cells is an important challenge for the years to come. The mechanism of glucose-dependent reversible dissociation of V-ATPase is starting to be resolved. Its significance in vesicular trafficking is of interest because the levels of glucose are tightly controlled in multicellular organisms. It becomes increasingly clear that reversible dissociation of V-ATPase is controlled by a variety of other cellular pathways and the potential regulatory role of small GTPases in the assembly/disassembly of VOV1 awaits further studies.

Our understanding of vesicle trafficking will be reinforced by further studies of V-ATPase as a pH-sensor and identification of effectors downstream of V-ATPase/GTPase complex. In particular the direct role of V-ATPase as pH-sensor and recruitment of small GTPases is of interest for the formation of endosomal carrier vesicles (ECV/MVB) because emerging evidence suggest that these vesicles are involved in biogenesis and function of exosomes. Thus the potential regulatory role of V-ATPase in the formation and/or secretion of exosomes also awaits further studies.

Emerging evidence also suggests possible interplay between assembly/disassembly of VOV1 and the direct role of VO in membrane fusion during vesicular trafficking. The relevant important questions that remain to be addressed are: first, does disassembly of V-ATPase take place during the budding process and, thus, is associated with the formation of carrier vesicles from the donor membrane? or second, does disassembly of V-ATPase take place nearby the acceptor-membrane before fusion and, is associated with uncoating of vesicles?

Increasing evidence has shown that V-ATPase can interact with numerous regulatory proteins. Cascades of different protein–protein interactions modulate targeting, assembly and activity of V-ATPase, followed by the regulation of intravesicular acidification and trafficking. Defective V-ATPase function can impair vesicular trafficking and give rise to human diseases. Thus, future studies will further shed light on the direct roles of this magnificent nano-motor in the regulation of vesicular trafficking and will undoubtedly contribute to the development of new drugs specifically targeting V-ATPase function.

References and recommended reading

Paper of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

Original work in the authors’ laboratories is supported by NIH (National Institutes of Health) grant DK038452 and BADERC (Boston Area Diabetes Research Center) grant DK057521-08 (VM) and by CREST, the Japan Science and Technology Agency, and the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (MF). MF is also grateful for the support of Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd and Eisai Co. Ltd.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2008.03.015.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Aridor G., Hannan L.A. Traffic Jam II: an update of diseases of intracellular transport. Traffic. 2002;3:781–790. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.31103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown D., Marshansky V. Renal V-ATPase: physiology and pathophysiology. In: Futai M., Wada Y., Kaplan J.H., editors. Handbook of ATPases: Biochemistry, Cell Biology, Pathophysiology. Wiley–VCH; Weinheim: 2004. pp. 413–442. [Google Scholar]

- 3••.Forgac M. Vacuolar ATPases: rotatory proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;11:917–929. doi: 10.1038/nrm2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a recent comprehensive review on biochemistry, physiology and pathophysiology of V-ATPase.

- 4.Nishi T., Forgac M. The vacuolar (H+)-ATPases-nature's most versatile proton pumps. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:94–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Futai M., Sun-Wada G.H., Wada Y. Proton translocating ATPases: introducing unique enzymes coupling catalysis and proton translocation through mechanical rotation. In: Futai M., Wada Y., Kaplan J.H., editors. Handbook of ATPases: Biochemistry, Cell Biology, Pathophysiology. Wiley–VCH; Weinheim: 2004. pp. 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beyenbach K.W., Wieczorek H. The V-type H+ ATPase: molecular structure and function, physiological roles and regulation. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:577–589. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith A.N., Lovering R.C., Futai M., Takeda J., Brown D., Karet F.E. Revised nomenclature for mammalian vacuolar-type H+-ATPase subunit genes. Mol Cell. 2003;12:801–803. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sambong Y., Iko Y., Tanabe M., Omote H., Iwamoto-Kihara A., Ueda I., Yanagida T., Wada Y., Futai M. Mechanical rotation of the c subunit oligomer in ATP synthase (FoF1): direct observation. Science. 1999;286:1722–1724. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9••.Itoh H., Takahashi A., Adachi K., Noji H., Yasuda R., Yoshida M., Kinosita K. Mechanically driven ATP synthesis by F1-ATPase. Nature. 2004;247:465–468. doi: 10.1038/nature02212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is an important study showing first evidence that mechanical rotation of ATP-synthase in the appropriate direction actually drives chemical reaction of ATP synthesis and resulted in the appearance of ATP in the medium.

- 10•.Nakanishi-Matsui M., Kashiwagi S., Ubukata T., Iwamoto-Kihara A., Wada Y., Futai M. Rotational catalysis of Escherichia coli ATP synthase F1 sector: stochastic fluctuation and a key domain of the β subunit. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20698–20704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A recent systematic study of rotational catalysis and stochastic fluctuations of bacterial ATP-synthase. The experimental design and movie showing rotation this nano-motor is presented in Supplementary Materials of this review.

- 11•.Hirata T., Iwamoto-Kihara A., Sun-Wada G.H., Okijama T., Wada Y., Futai M. Subunit rotation of vacuolar-type proton pumping ATPase: relative rotation of the G and c-subunits. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23714–23719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A key paper that observed subunit rotation of yeast vacuolar-ATPase for the first time. An actin filament connected to G-subunit rotated in V-ATPase immobilized on glass surface through c-subunit. The experimental design and movie showing rotation this nano-motor is presented in Supplementary Materials of this review.

- 12.Sun-Wada G.H., Wada Y., Futai M. Diverse and essential roles of mammalian vacuolar-type proton pump ATPase: toward the physiological understanding of inside acidic compartments. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1658:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner C.A., Finberg K.E., Breton S., Marshansky V., Brown D., Geibel J.P. Renal vacuolar H+-ATPase. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1263–1314. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karet F.E. Mutations in the gene encoding B1 subunit of H+-ATPase cause renal tubular acidosis with sensorineural deafness. Nat Genet. 1999;21:84–90. doi: 10.1038/5022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith A.N., Borthwick K.J., Karet F.E. Molecular cloning and characterization of novel tissue-specific isoforms of the human vacuolar H+-ATPase C, G and d sudunits, and their evaluation in autosomal recessive distal renal tubular acidosis. Gene. 2002;297:169–177. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00884-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishi T., Kawasaki-Nishi S., Forgac M. Expression and function of the mouse V-ATPase d subunit isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46396–46402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun-Wada G.H., Imai-Senga Y., Yamamoto A., Murata Y., Hirata T., Wada Y., Futai M. A proton pump ATPase with testis specific E1-subunit isoform required for acrosome acification. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18098–18105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun-Wada G.H., Yoshimizu T., Imai-Senga Y., Wada Y., Futai M. Diversity of mouse proton-translocating ATPase: presence of multiple isoforms of the C, d and G subunits. Gene. 2003;302:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun-Wada G.H., Murata Y., Namba M., Yamamoto A., Wada Y., Futai M. Mouse proton pump ATPase C subunit isoforms (C2-a and C2-b) specifically expressed in kidney and lung. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44843–44851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murata Y., Sun-Wada G.H., Yoshimizu T., Yamamoto A., Wada Y., Futai M. Differential localization of the vacuolar H+ pump with G subunit isoforms (G1 and G2) in mouse neurons. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36296–36303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norgett E.E., Borthwick K.J., Al-Lamki R.S., Su Y., Smith A.N., Karet F.E. V1 and Vo-domains of the human H+-ATPase are linked by an interaction between the G and a subunits. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14421–14427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Kawasaki-Nishi S., Bowers K., Nishi T., Forgac M., Stevens T.H. The amino-terminal domain of the vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase a-subunit controls targeting and in vivo dissociation, and the carboxyl-terminal domain affects coupling of proton transport and ATP hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47411–47420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper provides evidence that in yeast V-ATPase N-terminal domain of a-subunit (Stv1p and Vph1p) is responsible for differential targeting (Golgi or vacuole) and dissociation, while C-terminal regulates energy coupling.

- 23•.Wassmer T., Kissmehl R., Cohen J., Plattner H. Seventeen a-subunit isoforms of Paramecium V-ATPase provide high specialization and function. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:917–930. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper provides intriguing data showing amazing diversity of a-subunit isoforms in Paramecium tetraurelia, in which 17 genes encoding V-ATPase different a-subunit isoforms were identified. Also surprisingly, that in contrast to yeast the targeting signal of Paramecium a-isoforms is located in C-terminus of the protein.

- 24.Toyomura T., Oka T., Yamaguchi C., Wada Y., Futai M. Three subunit a isoforms of mouse vacuolar H+-ATPase: differential expression of the a3 isoform during osteoclast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8760–8765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oka T., Murata Y., Namba M., Yoshimizu T., Toyomura T., Yamamoto A., Sun-Wada G.H., Hamasaki N., Wada Y., Futai M. a4, a unique kidney-specific isoform of mouse vacuolar H+-ATPase subunit a. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40050–40054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith A.N., Finberg K.E., Wagner C.A., Lifton R.P., Devonald M.A.J., Su Y., Karet F.E. Molecular cloning and characterization of Atp6n1b: a novel fourth murine vacuolar H+-ATPase a-subunit gene. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42382–42388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishi T., Forgac M. Molecular cloning and expression of three isoforms of the 100-kDa a-subunit of the mouse vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6824–6830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28••.Toyomura T., Murata Y., Yamamoto A., Oka T., Sun-Wada G.H., Wada Y., Futai M. From lysosomes to the plasma membrane: localization of vacuolar type H+-ATPase with the a3-isoform during osteoclast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22023–22030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This important study on RAW264.7 cells suggests that V-ATPase with a3-isoform localized in late endosomes/lysosomes are transported to cell periphery and finally assembled in membranes of mature osteoclasts.

- 29•.Sun-Wada G.H., Toyomura T., Murata Y., Yamamoto A., Futai M., Wada Y. The a3 isoform of V-ATPase regulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4531–4540. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper provides evidence on regulatory role of a3-isoform in insulin secretion by pancreatic β-cells. The oc/oc mice, which have a null mutation at a3 locus, exhibit an impaired insulin secretion from isolated islets. V-ATPase a3-isoform was suggested to be directly involved in fusion events because it could not be replaced by functional a2-isoform in these cells.

- 30••.Hurtado-Lorenzo A., Skinner M., El Annan J., Futai M., Sun-Wada G.H., Bourgoin S., Casanova J., Wildeman A., Bechoua S., Ausiello D.A. V-ATPase interacts with ARNO and Arf6 in early endosomes and regulates the protein degradative pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:124–136. doi: 10.1038/ncb1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper provides key evidence of direct acidification-dependent interaction of V-ATPase with Arf-family small GTPases, which are well known regulatory proteins of vesicular trafficking and organelle biogenesis. Authors suggested, that in addition to its function as a proton pump, V-ATPase itself is also functioning as endosomal pH-sensor.

- 31••.Kornak U., Reynders E., Dimopoulou, Van Reeuwijk J., Fischer B., Rajab A., Budde B., Nurnberg P., Foulquier F., Lefeber D. Impaired glycosylation and cutis laxa caused by mutations in the vesicular H+-ATPase subunit ATP6V0A2. Nat Gen. 2008;40:32–34. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first study which identifies loss-of-function mutations of human a2-subunit of V-ATPase as a cause of human disease. Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are caused by defective protein glycosylation and, thus, this study indicate that the a2-subunit of V-ATPase may play an important role in Golgi function.

- 32.Pietrement C., Sun-Wada G.H., Da Silva N., McKee M., Marshansky V., Brown D., Futai M., Breton S. Distinct expression patterns of different subunit isoforms of the V-ATPase in the rat epididymis. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:185–194. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morel N., Dedieu J.C., Philippe J.M. Specific sorting of the a1-isoform of the V-H+-ATPase a subunit to nerve terminals where it associated with both synaptic vesicles and the presynaptic plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4751–4762. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kane P.M. The where, when and how of organelle acidification by the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. Microbiol Mol Biol Rew. 2006;70:177–191. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.177-191.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35••.Lu M., Sautin Y.Y., Holiday S., Gluck S.L. The glycolytic enzyme aldolase mediates assembly, expression, and activity of vacuolar H+-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8732–8739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is first paper which identified an important role the glycolytic enzyme aldolase in glucose-dependent reversible assembly/disassembly of V-ATPase in mammalian cells.

- 36.Sautin Y.Y., Lu M., Gaugler A., Zhang L., Gluck S.L. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mediated effects of glucose on vacuolar H+-ATPase assembly, translocation, and acidification of intracellular compartments in renal epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:575–589. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.575-589.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu M., Ammar D., Ives H., Albrecht F., Gluck S. Physical interaction between aldolase and vacuolar H+-ATPase is essential for the assembly and activity of the proton pump. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24495–24503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawasaki-Nishi S., Nishi T., Forgac M. Yeast V-ATPase complexes containing different isoforms of the 100-kDa a-subunit differ in coupling efficiency and in vivo dissociation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17941–17948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39•.Shao E., Forgac M. Involvement of the nonhomologous region of subunit A of the yeast V-ATPase in coupling and in vivo dissociation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48663–48670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrated that in yeast the dissociation of V-ATPase in response to glucose-depletion depends upon vacuolar acidification.

- 40.Qi J., Forgac M. Cellular environment is important in controlling V-ATPase dissociation and its dependence on activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24743–24751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700663200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41••.Trombetta E.S., Ebersold M., Garrett W., Pypaert M., Mellman I. Activation of lysosomal function during dendritic cell maturation. Science. 2003;299:1400–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.1080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An important study demonstrating the regulation of V-ATPase activity by the assembly of VOV1 sectors onto lysosomal membrane as a part of functional maturation of dendritic cells in vivo. This mechanism is critical for lysosomal acidification, activation of proteases, protein degradation, and antigen presentation.

- 42.Pastor-Soler N., Beaulieu V., Litvin T.N., Da Silva N., Chen Y., Brown D., Buck J., Levin L.R., Breton S. Bicarbonate-regulated adenylyl cyclase (sAC) is a sensor that regulates pH-dependent V-ATPase recycling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49523–49529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309543200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Breton S., Brown D. New insights into the regulation of V-ATPase-dependent proton secretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1–F10. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00340.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheel O., Zdebik A.A., Lourdel S., Jentsch T.J. Voltage-dependent electrogenic chloride/proton exchange by endosomal CLC proteins. Nature. 2005;436:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature03860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jentsch T.J. Chloride and the endosomal-lysosomal pathway: emerging role of CLC chloride transporters. J Physiol. 2007;578:633–640. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46••.Steinberg B.E., Touret N., Vargas-Caballero M., Grinstein S. In situ measurement of the electrical potential across the phagosomal membrane using FRET and its contribution to the ptoron-motive force. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9523–9528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700783104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is an excellent study providing measurements of the components of the proton-motive force generated by V-ATPase located on intracellular phagosomal membrane in live macrophages. The molecular mechanisms of the balance between electrical and chemical components are discussed in relation to phagosomal function.

- 47.Sonawane H.D., Thiagarajah J.R., Verkman A.S. Chloride concentration in endosomes measured using a ratioable fluorescent Cl− indicator: evidence for chloride accumulation during acidification. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5506–5513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110818200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orlowski J., Grinstein S. Emerging roles of alkali cation/proton exchangers in organellar homeostasis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:483–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oka T., Toyomura T., Honjo K., Wada Y., Futai M. Four subunit a-isoforms of Caenorhabditis elegans vacuolar H+-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33079–33085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun-Wada G.H., Murata Y., Yamamoto A., Kanazawa H., Wada Y., Futai M. Acidic endomembrane organelles are required for mouse postimplantation development. Dev Biol. 2000;228:315–325. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mellman I. The importance of being acid: the role of acidification in intracellular membrane traffic. J Exp Biol. 1992;172:39–45. doi: 10.1242/jeb.172.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52•.Mellman I., Warren G. The road taken: past and future foundations of membrane traffic. Cell. 2000;100:99–112. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81687-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is an important visionary review of the past accomplishments and future directions in the field of vesicular trafficking research.

- 53.Marshansky V., Ausiello D.A., Brown D. Physilogical importance of endosomal acidification: potential role in proximal tubulopathies. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2002;11:527–537. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bonifacino J.S., Glick B.G. The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell. 2004;116:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55••.Peters C., Bayer M.J., Buhler S., Andersen J.S., Mann M., Mayer A. Trans-complex formation by proteolipid channels in the terminal phase of membrane fusion. Nature. 2001;409:581–588. doi: 10.1038/35054500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first study showing the direct role of V-ATPase in yeast vacuole membrane fusion.

- 56.Bayer M.J., Reese C., Buhler S., Peters C., Mayer A. Vacuole membrane fusion: Vo functions after trans-SNARE pairing and is coupled to the Ca2+-releasing channel. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:211–222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baars T.L., Petri S., Peters C., Mayer A. Role of the V-ATPase in regulation of the vacuolar fission-fusion equilibrium. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3873–3882. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hiesinger P.R., Fayyazuddin A., Mehta S.Q., Rosenmund T., Schulze K.L., Zhai R.G., Verstreken P., Cao Y., Zhou Y., Kunz J., Bellen H.J. The V-ATPase Vo subunit a1 is required for a late step in synaptic vesicle exocytosis in Drosophila. Cell. 2005;121:607–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhahg W., Wang D., Volk E., Bellen H.J., Hiesinger P.R., Quiocho F.A. V-ATPase Vo sector subunit a1 in neurons is a target of calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:294–300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708058200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liegeois S., Benedetto A., Garnier J.M., Schwab Y., Labouesse M. The Vo-ATPase mediates apical secretion of exosomes containing Hedgehog-related proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:949–961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clare D.K., Orlova E.V., Finbow M.A., Harrison M.A., Findlay J.B.C., Saibil H.R. An expanded and flexible form of the vacuolar ATPase membrane sector. Structure. 2006;14:1149–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun-Wada G.H., Tabata H., Kawamura N., Futai M., Wada Y. Differential expression of a subunit isoforms of the vacuolar-type proton pump ATPase in mouse endocrine tissue. Cell Tiss Res. 2007;329:239–248. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0421-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frattini A., Orchard P.J., Sobacchi C., Giliani S., Abinun M., Mattsson J.P., Keeling D.J., Andersson A.K., Wallbrandt P., Zecca L. Defects in TCIRG1 subunit of the vacuolar proton pump are responsible for a subset of human autosomal recessive osteopetrosis. Nat Gen. 2000;25:343–346. doi: 10.1038/77131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kornak U., Schulz A., Friedrich W., Uhlhaas S., Kremens B., Voit T., Hasan C., Bode U., Jentsch T.J., Kubisch C. Mutations in the a3 subunit of the vacuolar H+-ATPase cause infantile malignant oeteopetrosis. Hum Mol Gen. 2000;9:2059–2063. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.13.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scimeca J.C., Franchi A., Trojani C., Parrinello H., Grosgeorge J., Robert C., Jaillon O., Poirier C., Gaudray P., Carle G.F. The gene encoding the mouse homologue of the human osteoclast-specific 116-kDa V-ATPase subunit bears a deletion in osteosclerotic (oc/oc) mutants. Bone. 2000;26:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith A.N., Jouret F., Bord S., Borthwick K.J., Al-Lamki R.S., Wagner C.A., Ireland D.C., Cormier-Daire V., Frattini A., Villa A. Vacuolar H+-ATPase d2 subunit: molecular characterization, developmental regulation, and localization to specialized proton pumps in kidney an bone. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1245–1256. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67••.Lee S.H., Rho J., Jeong D., Sul J.Y., Kim T., Kim N., Kang J.S., Miyamoto T., Suda T., Lee S.K. V-ATPase Vo subunit d2-deficient mice exhibit impaired osteoclast fusion and increased bone formation. Nat Med. 2006;12:1403–1409. doi: 10.1038/nm1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This recent paper identifies an important role of V-ATPase Vo subunit d2-isoform in osteoclast fusion and bone formation in mouse model in vivo.

- 68.Gruenberg J., van derGoot F.G. Mechanisms of pathogen entry through the endosomal compartments. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:495–504. doi: 10.1038/nrm1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huynh K.K., Grinstein S. Regulation of vacuolar pH and its modulation by some microbial species. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:452–462. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00003-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abrami L., Lindsay M., Parton R.G., Leppla S.H., Van der Goot F.G. Membrane insertion of anthrax protective antigen and cytoplasmic delivery of lethal factor occur at different stages of the endocytic pathway. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:645–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gibert M., Marvaud J.C., Pereira Y., Hale M.L., Stiles B.G., Boquet P., Lamaze C., Popoff M.R. Differential requirement for the translocation of clostridial binary toxins: Iota toxin requires a membrane potential gradient. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mandic R., Fackler O.T., Geyer M., Linnemann T., Zheng Y.H., Peterlin B.M. Negative factor from SIV binds to the catalytic subunit of the V-ATPase to internalize CD4 and to increase viral infectivity. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:463–473. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Geyer M., Fackler O.T., Peterlin B.M. Subunit H of the V-ATPase involved in endocytosis shows homology to β-adaptins. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2045–2056. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Geyer M., Yu H., Mandic R., Linnemann T., Zheng Y.H., Fackler O.T., Peterlin B.M. Subunit H of the V-ATPase binds to the medium chain of adaptor protein complex 2 and connects Nef to the endocytic machinery. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28521–28529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clague M.J., Urbe S., Aniento F., Gruenberg J. Vacuolar ATPase activity is requited for endosomal carrier vesicle formation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76••.Trajkovic K., Hsu C., Chiantia S., Rajendran L., Wenzel D., Wieland F., Schwille P., Brugger B., Simons M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319:1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Recent paper that establish a novel pathway in intraendosomal membrane transport and exosome formation.

- 77.Aniento F., Gu F., Parton R.G., Gruenberg J. An endosomal β-COP is involved in the pH-dependent formation of transport vesicles destined for late endosomes. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:29–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gu F., Gruenberg J. Arf1 regulates pH-dependent COP function in the early endocytic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8154–8160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.El Annan J., Brown D., Breton S., Bourgoin S., Ausiello D.A., Marshansky V. Differential expression and targeting of endogenous Arf1 and Arf6 small GTPases in kidney epithelial cells in situ. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C768–C778. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00250.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maranda B., Brown D., Bourgoin S., Casanova J.E., Vinay P., Ausiello D.A., Marshansky V. Intra-endosomal pH-sensitive recruitment of the Arf-nucleotide exchange factor ARNO and Arf6 from cytoplasm to proximal tubule endosomes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18540–18550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Recchi C., Chavrier P. V-ATPase: a potential pH sensor. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:107–109. doi: 10.1038/ncb0206-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marshansky V. The V-ATPase a2-subunit as a putative endosomal pH-sensor. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1092–1099. doi: 10.1042/BST0351092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bourne H.R., Sanders D.A., McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: a conserved switch for diverse cell functions. Nature. 1990;348:125–132. doi: 10.1038/348125a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Donaldson J.G., Klausner R.D. ARF: a key regulatory switch in membrane traffic and organelle structure. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:527–532. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85••.D'Souza-Schorey C., Chavrier P. ARF proteins: role in membrane traffic and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:347–358. doi: 10.1038/nrm1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a comprehensive review on biochemistry and cell biology of Arf-family small GTPases and their role in regulation of vesicular trafficking and organelle structure.

- 86.Chen S.H., Bubb M.R., Yarmola E.G., Zuo J., Jiang J., Lee B.S., Lu M., Gluck S.L., Hurst I.R., Holliday L.S. Vacuolar H+-ATPase binding to microfilaments: regulation in response to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity and detailed characterization of the actin-binding site in subunit B. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7988–7998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Myers K.R., Casanova J.E. Regulation of actin cytoskeleton dynamics by Arf-family GTPases. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bourgoin S.G., Houle M.G., Singh I.N., Harbour D., Gagnon S., Morris A.J., Brindley D.N. ARNO but not cytohesin-1 translocation is phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent in HL-60 cells. J Leuk Biol. 2002;71:718–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Venkateswarlu K., Brandom K.G., Yun H. PI-3-kinase-dependent membrane recruitment of centaurin-a2 is essential for its effect on Arf6-mediated actin cytoskeleton reorganization. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:792–801. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.