Abstract

Heart failure (HF), with steadily increasing incidence rates and mortality in an ageing population, represents a major challenge. Evidence suggests that more than half of all patients with a diagnosis of HF suffer from HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Emerging novel biomarkers to improve and potentially guide the treatment of HFpEF are the subject of discussion. One of these biomarkers is suppression of tumourigenicity 2 (ST2), a member of the interleukin (IL)-1 receptor family, binding to IL-33. Its two main isoforms – soluble ST2 (sST2) and transmembrane ST2 (ST2L) – show opposite effects in cardiovascular diseases. While the ST2L/IL-33 interaction is considered as being cardioprotective, sST2 antagonises this beneficial effect by competing for binding to IL-33. Recent studies show that elevated levels of sST2 are associated with increased mortality in HF with reduced ejection fraction. Nevertheless, the significance of sST2 in HFpEF remains uncertain. This article aims to give an overview of the current evidence on sST2 in HFpEF with an emphasis on prognostic value, clinical association and interaction with HF treatment. The authors conclude that sST2 is a promising biomarker in HFpEF. However, further research is needed to fully understand underlying mechanisms and ultimately assess its full value.

Keywords: Heart failure, biomarker, suppression of tumourigenicity 2, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

Heart failure (HF) is a chronic, progressive disease with steadily increasing incidence rates and high morbidity and mortality that represents a major challenge in healthcare worldwide.[1–3] The disease is characterised by chronic exacerbations, recurrent hospitalisations and poor prognosis.[1,2] Survival rates in HF patients are lower than in patients suffering from some malignant diseases, including breast cancer and prostate cancer.[3] Epidemiological data suggest that between a third and more than half of all HF patients suffer from HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).[4,5] For some time, investigators have been discussing an inferior prognosis in HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) compared with HFpEF.[6,7] However, several recent studies suggest that survival rates for patients with HFpEF and patients with HFrEF are similar.[4,8–12]

With its poor prognosis and prevalence rates that are expected to increase further in an ageing population, new approaches to the diagnostics and treatment of HFpEF are increasingly important.[4,5,13] However, there is still a lack of established diagnostic standards and therapies because of unresolved challenges in this complex disease entity.

Several studies have evaluated the role of emerging novel biomarkers in this field.[14–16] Systemic inflammation, fibrosis and cardiac remodelling are central features in the pathophysiology of HFpEF.[17–19] Suppression of tumourigenicity 2 (ST2) – a receptor suggested to indicate and reflect these complex underlying processes – has therefore been discussed as a promising biomarker.[20] The prognostic value of ST2 in HFpEF, as well as its association with clinical features and interaction with HF treatment, are the main subject of this article.

ST2 and its Relationship with Heart Failure

The Biology of ST2

ST2 is a member of the interleukin (IL)-1 receptor family.[20] First described in 1989 by Tominaga et al., its role as a marker in myocardial injury was initially suggested in 2002 by Weinberg et al.[21,22]

Four different isoforms of ST2 – with a soluble (sST2) and a transmembrane receptor (ST2L) at the centre of attention – were detected and IL-33 was identified as their ligand.[20,23] IL-33 – a cytokine that belongs to the IL-1 family – is released by a multitude of different cell types in different situations, such as during mechanical stress, among others.[20,24]

ST2L and sST2 promote opposing biological effects by binding to IL-33. The ST2L/IL-33 interaction initiates a complex cardioprotective biochemical cascade that counteracts hypertrophic and fibrotic processes and protects cells from apoptosis. However, in times of cardiac damage, cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts and extracardiac cells secrete large amounts of sST2. By competing for the IL-33 binding site, circulating sST2 antagonises those cardioprotective mechanisms and thereby promotes myocardial damage (Figure 1).[20,25]

Figure 1: Schematic Illustration of ST2/IL-33 Interaction.

ST2 is a member of the IL-1 receptor family consisting of two main isoforms – a transmembrane (ST2L) and a soluble receptor (sST2). The cytokine IL-33, known to be its ligand, is produced by many cells (e.g. fibroblasts etc.) in the presence of injury and stress. When IL-33 binds transmembrane ST2L located on different cells (e.g. myocytes, fibroblasts, immune cells), a complex cardioprotective biochemical cascade is launched, leading to a reduction of myocardial fibrosis, prevention of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and protection from apoptosis. However, in times of cardiac damage and stress cardiac fibroblasts, cardiomyocytes and extracardiac cells produce sST2. By binding IL-33, and therefore competing for the binding site, excessive amounts of sST2 interrupt the cardioprotective interaction of IL-33 and ST2L. IL = interleukin; ST2 = suppression of tumourigenicity 2. Source: Pascual-Figal and Januzzi 2015.[20] Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

Clinical Relevance of sST2 in Cardiovascular Disease and Heart Failure

After observing elevated sST2 levels in patients after MI, its clinical value as a biomarker for cardiac stress and mechanical overload was first discussed.[22] The marker’s prognostic potential arose after an analysis of sST2 levels in >800 patients with acute ST-elevation MI. A significant association between increased sST2 levels and higher 30- day mortality was described.[26,27]

Furthermore, because myocardial strain, fibrosis and volume overload are common features in the pathophysiology of congestive HF, researchers also suggested a prognostic, as well as a diagnostic, value of sST2 in this disease entity.[26,28,29] Analyses of blood samples from the Prospective Randomized Amlodipine Survival Evaluation 2 (PRAISE-2) HF trial and the Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department (PRIDE) trial found increased levels of sST2 in patients with severe, acute decompensated HF (ADHF) with reduced ejection fraction. In addition, both trials also identified sST2 levels as a predictor of outcome in this disease entity.[28–31] Subsequently, the findings of several other studies supported these data and highlighted the role of sST2 as a promising prognostic biomarker in HFrEF.[32–35]

In view of these findings, many investigators are exploring the potential value of sST2 being integrated into the routine work-up and treatment of HF patients. Maisel et al. described sST2 as the HbA1c of HF and considered the biomarker capable of depicting a bigger picture of the disease and its underlying mechanisms including inflammatory processes and fibrosis.[36]

Hence, the measurement of biomarkers indicating myocardial injury and fibrosis was included in the 2017 American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association/Heart Failure Society of America guidelines for the management of HF as a class IIa recommendation in patients with chronic HF.[37] However, the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic HF do not explicitly recommend the measurement of such biomarkers in routine clinical settings.[38]

While the promising role of sST2 as a biomarker in HFrEF is supported by increasing evidence, several aspects of this biomarker still remain unclear and call for further investigation. One aspect is that no consensus on a standardised reference interval has been reached. Indeed, different values for European compared with US populations, as well as sex-specific cut-offs, have been described.[36,39–42] Furthermore, data investigating the value of sST2 in HF with mid-range or preserved ejection fraction are sparse and, therefore, its significance as a biomarker in this disease remains uncertain.

Systemic Inflammation and Cardiac Remodelling: Pathophysiological Pathways

The pathophysiology of HFpEF is complex and not entirely understood. However, it is essential to consider underlying mechanisms to assess the role of biomarkers in this disease. In general, systemic inflammation and microvascular dysfunction, along with cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and fibrosis, are believed to play a key role in the pathophysiology of HFpEF.[17,18,43–46]

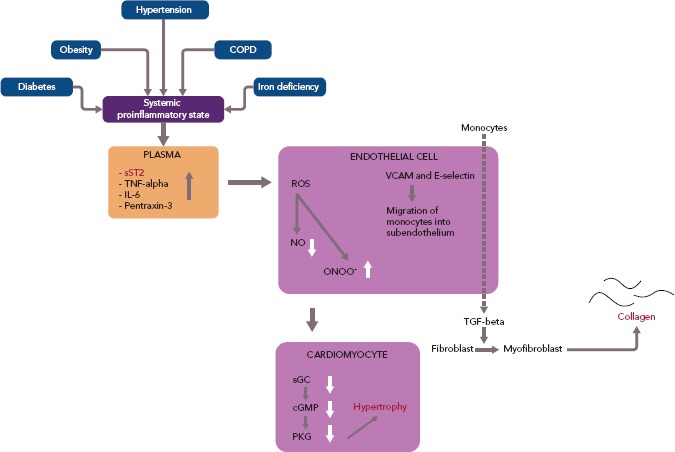

Paulus et al. suggested that some of those cardiac modifications derive from common comorbidities in HFpEF, such as diabetes, obesity, hypertension and physical inactivity. These diseases are considered to induce a state of systemic inflammation with increased levels of sST2 and other inflammatory agents, consequently triggering a complex signalling cascade initiating cardiac remodelling and leading to diastolic myocardial dysfunction (Figure 2).[17]

Figure 2: The Role of Comorbidities and Inflammatory Agents Including sST2 in the Pathophysiology of HFpEF.

Common comorbidities, including diabetes, obesity and hypertension, generate a systemic proinflammatory state characterised by increased levels of sST2, TNF-alpha, IL-6 and pentraxin-3. These factors trigger the production of ROS, VCAM and E-selectin in coronary endothelial cells. The accumulation of ROS induces the synthesis of ONOO- and causes a decrease in the supply of NO. The impact of ONOO- and NO on sGC and cGMP in adjoining cardiomyocytes subsequently leads to a reduction in the activity of PKG. The latter, in consequence, activates a complex prohypertrophic cascade resulting in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. VCAM and E-selectin accumulation, however, sets monocytes in motion that migrate into subendothelium and produce TGF-beta. TGF-beta, in turn, induces the transformation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, which then produce collagen. cGMP = cyclic guanosine monophosphate; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HFpEF = preserved ejection fraction; IL = interleukin; NO = nitric oxide; ONOO- = peroxynitrite; PKG = protein kinase G; ROS = reactive oxygen species; sGC = soluble guanylate cyclase; sST2 = soluble suppression of tumourigenicity 2; TGF-beta = transforming growth factor-beta; TNF-alpha = tumour necrosis factor-alpha; VCAM = vascular cell adhesion molecule. Source: Paulus et al. 2013.[17] Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

Increased levels of sST2 could mark the activation of this pathophysiological pathway. Therefore, researchers expect to gain important information through the collection of sST2 levels in patients with suspected HFpEF. The utility of this biomarker as a diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic tool in this disease entity is the subject of discussion.

Prognostic Value of sST2

Several studies provide evidence of a significant association between increased sST2 levels and outcome in HFpEF. Five predominantly retrospective/post-hoc analyses with cohort sizes ranging from 86 to 200 patients showed increased sST2 levels mostly measured at baseline to significantly correlate with increased mortality, as well as with increased hospitalisation rates at different periods of follow-up.[47–51] In contrast, two studies with cohort sizes of 76 and 135 patients delivered contradictory results. Friões et al. reported that there was no significant association between increased sST2 levels and and a composite endpoint of all-cause death or hospital readmission for HF within 6 months, while Moliner et al. reported no association with cardiovascular death or HF-related hospitalisation/all-cause death or HF-related hospitalisation (Table 1).[52,53]

Table 1: Studies Investigating the Prognostic Value of sST2 in HFpEF.

| Study and Year | n | Type of Analysis | LVEF | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shah et al. 2011[47] | 200 | Post hoc | ≥50% | Association between increased baseline sST2 levels and increased 1-year mortality (p=0.001) |

| Manzano-Fernández et al. 2011[48] | 197 | Retrospective | ≥50% | Association between increased baseline sST2 levels and increased 1-year mortality (p=0.002) |

| Friões et al. 2015[52] | 76 | Retrospective | ≥50% | No association between increased sST2 levels measured at discharge after hospitalisation for ADHF and a composite endpoint of all-cause death or hospital readmission for HF within 6 months (p=0.07) |

| Sanders-van Wijk et al. 2015[49] | 100 | Post hoc | ≥50% | Association between increased baseline sST2 levels and decreased 18-month overall survival and HF hospitalisation-free survival (p=0.002) |

| Moliner et al. 2018[53] | 135 | Retrospective | ≥50% | No association between increased baseline sST2 levels and cardiovascular death or HF-related hospitalisation (p=0.79) and all-cause death or HF-related hospitalisation (p=0.44; mean follow-up period 4.9 ± 2.8 years) |

| Najjar et al. 2019[50] | 86 | Retrospective | ≥45% | Association between increased sST2 levels 4–8 weeks (stable condition) after enrolment and a composite endpoint of death or HF hospitalisation (median follow-up of 522 days; p=0.046) |

| Sugano et al. 2019[51] | 191 | Post hoc | ≥50% | Association between increased baseline sST2 levels and increased all-cause death and non- cardiovascular death (median follow-up 445 days; p=0.002, p=0.003) |

ADHF = acute decompensated heart failure; HF = heart failure; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; sST2 = soluble suppression of tumourigenicity 2.

Association Between sST2, Clinical Parameters and Echocardiographic Measurements

In 2011, Shah et al. published results of an investigation of 200 patients presenting to the emergency department with worsening dyspnoea but preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).[47] At enrolment, sST2 concentrations correlated with elevated levels of N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), myeloperoxidase and C-reactive protein (CRP), as well as with decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), previous diagnosis of ADHF and older age. However, sST2 lagged behind NT-proBNP regarding the association with echocardiographic measurements and indices of diastolic dysfunction. In summary, sST2 was not associated with left ventricular (LV) mass and most indices of diastolic dysfunction in patients with an LVEF ≥50%.[47]

In a study by Manzano-Fernández et al., sST2 levels were measured in 447 patients with ADHF.[48] The investigators sought to analyse the association of sST2 with mortality, both in HFrEF and HFpEF. Higher levels of sST2 were associated clinically with more severe HF symptoms in both subgroups. In patients with HFpEF increased baseline levels of sST2 were associated with higher levels of leukocytes, creatinine, eGFR, CRP, NT-proBNP and troponin T. Again, the study failed to provide evidence of a significant association with relevant echocardiographic parameters in HFpEF.[48]

Zile et al. evaluated data from the Prospective comparison of ARNI with ARB on Management Of heart failUre with preserved ejectioN fracTion (PARAMOUNT) trial. In a group of 301 patients NT-proBNP, matrix metalloproteinase-2, collagen III N-terminal propeptide, galectin-3 and sST2 were measured at baseline and 12 and 36 weeks after randomisation.[54] Levels of sST2 were higher than reference values in comparable control groups determined in previous investigations.[39,40,54] In line with previous results, there was evidence of an association between higher baseline levels of sST2 and higher levels of NT-proBNP, as well as reduced renal function. In contrast to previous findings, worsening degrees of diastolic dysfunction measured through an increase in E/E’ and left atrial (LA) volume during follow-up were found to be associated with an increase in sST2 values during follow-up. However, only the correlation with LA volume showed statistical significance. Further adjusted multivariate statistical analysis only found female sex, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class and LA volume to significantly correlate with elevated sST2 levels.[54]

AbouEzzedine et al. analysed serum sST2 levels from 174 patients enrolled in the Effect of Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibition on Exercise Capacity and Clinical Status in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (RELAX) trial.[55,56] They found evidence of an association of increased baseline sST2 values with worse clinical signs and symptoms, including pronounced leg oedema, higher jugular venous pressure and again higher classes in the NYHA classification. Elevated sST2 levels were mainly found in patients with comorbidities, while there was no evidence of sST2 being linked to co-factors, such as body size, age or history of HF hospitalisation. In addition, while NT-proBNP levels again correlated strongly with echocardiographic measurements of diastolic dysfunction, sST2 values in this cohort failed to show this phenomenon and were only found to indicate malfunction of the right ventricle. Investigators concluded that sST2 in this setting is to be seen as a marker of systemic inflammation rather than as a measure of diastolic dysfunction.[55] This assumption is further supported by recurrent findings reporting increased levels of sST2 in various disease entities, including trauma, sepsis and pulmonary disease.[57,58]

Nagy et al. investigated the value of sST2 in 86 patients with HFpEF from the Karolinska Rennes study with special interest in its association with echocardiographic parameters.[59] SST2 levels were measured in a stable state of disease 4–8 weeks after a patient presented to the hospital with ADHF. Of note, their results showed a significant association between increased ST2 levels and reduced left atrial global strain, as well as reduced RV-function, but not with indices of LV geometrical diameters, LV functional parameters and several other measurements.[59] The findings discussed here are depicted in detail in Table 2.[47,48,50,51,54,55,59]

Table 2: Studies Investigating the Association Between sST2 and a Variety of Clinical Features in HFpEF.

| Study | n | Type of Analysis | LVEF | Clinical Features | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant Correlation | No Significant Correlation | ||||

| Shah et al. 2011[47] | 200 | Post hoc | ≥50% | Association between increased baseline sST2 levels and:

|

No association between increased baseline sST2 levels and:

|

| Manzano-Fernández et al. 2011[48] | 197 | Retrospective | ≥50% | Association between increased baseline sST2 levels and:

|

No association between increased baseline sST2 levels and:

|

| Zile et al. 2016[54] | 301 | Post hoc (PARAMOUNT) | ≥45% | Association between increased baseline sST2 levels and:

|

No association between increased baseline sST2 levels and:

|

| AbouEzzedine et al. 2017[55] | 174 | Post hoc (RELAX) | ≥50% | Association between increased baseline sST2 levels and:

|

No association between increased baseline sST2 levels and:

|

| Nagy et al. 2018[59] | 86 | Retrospective | ≥45% | Association between increased sST2 levels 4–8 weeks (stable condition) after enrolment and:

|

No association between increased sST2 levels 4–8 weeks (stable condition) after enrolment and:

|

| Najjar et al. 2019[50] | 86 | Retrospective | ≥45% | Association between increased sST2 levels 4–8 weeks (stable condition) after enrolment and:

|

No association between increased sST2 levels 4–8 weeks (stable condition) after enrolment and:

|

| Sugano et al. 2019[51] | 191 | Post hoc (ICAS-HF) | ≥50% | Association between increased baseline sST2 levels and:

|

No association between increased baseline sST2 levels and:

|

*Multivariable analysis adjusted for age, sex, NYHA class, history of AF, diastolic blood pressure, eGFR, log NT-proBNP, E/E’ and LA volume. †Adjusted for sex. ADHF = acute decompensated heart failure; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; BUN = blood urea nitrogen; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP = C-reactive protein; cTnI = cardiac troponin I; cTnT = cardiac troponin T; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; E’ = mean value of the lateral and septal mitral annular early diastolic velocity; E/A = ratio between early diastolic inflow velocity (E)/inflow velocity due to atrial contraction (A); E/E’ = early diastolic tissue velocity; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; Hb = haemoglobin; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HR = heart rate; LA = left atrium; LA-GS = left atrial global strain; LAVI = left atrial volume index; LV = left ventricle; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMI = left ventricular mass index; MPO = myeloperoxidase; NT-proBNP = N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA = New York Heart Association; RV = right ventricle; SBP = systolic blood pressure; sST2 = soluble suppression of tumourigenicity 2.

Comorbidities and sST2

Although common chronic diseases, such as diabetes, arterial hypertension and obesity, play a major role in HFpEF, data in this specific area are scarce. While on the one hand those diseases are frequently observed comorbidities in HFpEF patients, on the other hand their causal potential in HFpEF pathophysiology is debated.[17] Even though this dual role suggests a close connection to sST2 values, only two studies (AbouEzzedine et al. and Sugano et al.) evaluated associations between the biomarker and comorbidities in HFpEF. However, the results of these analyses were contradictory.[51,55] BMI was the only parameter that was evaluated by almost all investigators. Here again findings diverged, leaving many questions unresolved.[47,48,50,51]

Heart Failure Treatment and sST2

Beyond the existing evidence of an interaction between sST2 and treatment with beta-blockers, valsartan and spironolactone in patients with HFrEF, there are very limited data investigating the relationship between sST2 levels and the response to different treatment approaches in HFpEF.[33,60,61]

To date, only the PARAMOUNT investigators have addressed this issue, when they discussed the interaction between sacubitril/valsartan, valsartan and sST2 levels.[54] They analysed whether the effectiveness of treatment with LCZ696 could be predicted and measured using sST2 and other biomarkers. At 12 and 36 weeks, neither sST2 nor any of the other biomarkers interacted with the changes in NT-proBNP levels associated with LCZ696 treatment. However, baseline levels of sST2 were associated with the effects of treatment with LCZ696 or valsartan on LA volume after 36 weeks. In patients with sST2 levels below the median of 33 ng/ml at baseline, the change in LA volume after 36 weeks of treatment with LCZ696 was significantly higher when compared to valsartan than in those with baseline sST2 values above the median. In a comparison of baseline levels to post-treatment sST2 levels, sST2 values did not respond significantly to treatment with LCZ696 or valsartan.[54]

Currently there are no data on the interaction of sST2 and treatment with beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, such as spironolactone, diuretics and other commonly used agents in HFpEF.

Conclusion

In conclusion, sST2 is a promising novel biomarker, with a significant value as an outcome indicator in HFrEF. In contrast, the existing evidence in HFpEF remains uncertain.

So far, most studies agree on the promising value of sST2 in predicting outcomes in patients with HFpEF. Furthermore, data repeatedly show evidence of an association between increased levels of sST2 and higher NT-proBNP, decreased eGFR, high CRP levels and advanced clinical HF severity. In contrast, most analyses have failed to show a significant correlation with characteristic echocardiographic measurements and indices, which are prerequisites for the diagnosis of HFpEF.

Although comorbidities play a bimodal role in HFpEF, there are hardly any data analysing the value of sST2 in, for example, patients with both diabetes and HFpEF. Additional investigations in this area could answer remaining pathophysiological questions.

To date, most results on sST2 in HFpEF are derived from retrospective/ post-hoc analyses of acute HF cohorts with limited sample sizes. Thus, prospective data, as well as data evaluating the significance of sST2 in chronic HFpEF, are scarce. Furthermore, interactions between sST2 and commonly used therapeutic agents including, for example, beta blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and diuretics have not been investigated sufficiently, but data from the PARAMOUNT trial suggest a potential role of sST2 in the management of the treatment of HFpEF.

Future research should therefore focus on the predictive value, clinical associations and impact of sST2 on the response to different therapeutic approaches in HFpEF. Because recent studies suggest that aldosterone inhibits cardioprotective mechanisms promoted through IL-33/ST2L, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists could be of particular interest.[62]

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamberlain AM, Dunlay SM, Gerber Y et al. burden and timing of hospitalizations in heart failure: a community study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:184–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mamas MA, Sperrin M, Watson MC et al. Do patients have worse outcomes in heart failure than in cancer? A primary care-based cohort study with 10-year follow-up in Scotland. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1095–104. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson C, Vasan RS. Epidemiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail Clin. 2014;10:377–88. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hogg K, Swedberg K, McMurray J. Heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function; epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:317–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somaratne JB, Berry C, McMurray JJV et al. The prognostic significance of heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: a literature-based meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:855–62. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry C, Doughty RN, Granger C et al. The survival of patients with heart failure with preserved or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1750–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ et al. Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence and mortality in a population- based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1948–55. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tribouilloy C, Rusinaru D, Mahjoub H et al. Prognosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a 5 year prospective population-based study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:339–47. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS et al. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:260–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah KS, Xu H, Matsouaka RA et al. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2476–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng RK, Cox M, Neely ML et al. Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction in the Medicare population. Am Heart J. 2014;168:721–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsao CW, Lyass A, Enserro D et al. Temporal trends in the incidence of and mortality associated with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:678–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Boer RA, Daniels LB, Maisel AS et al. State of the art: newer biomarkers in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:559–69. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tromp J, Khan MAF, Klip IT et al. Biomarker profiles in heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Am Heart J. 2017;6:e003989. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Boer RA, Nayor M, deFilippi CR et al. Association of cardiovascular biomarkers with incident heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:215–24. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borbély A, van der Velden J, Papp Z et al. Cardiomyocyte stiffness in diastolic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:774–81. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155257.33485.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borlaug BA. The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:507–15. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pascual-Figal DA, Januzzi JL. The biology of ST2: the International ST2 Consensus Panel. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:3B–7B. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tominaga S. A putative protein of a growth specific cDNA from BALB/c-3T3 cells is highly similar to the extracellular portion of mouse interleukin 1 receptor. FEBS Lett. 1989;258:301–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinberg EO, Shimpo M, De Keulenaer GW et al. Expression and regulation of ST2, an interleukin-1 receptor family member, in cardiomyocytes and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;106:2961–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000038705.69871.D9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1- like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kakkar R, Hei H, Dobner S et al. Interleukin 33 as a mechanically responsive cytokine secreted by living cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:6941–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.298703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ et al. IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1538–49. doi: 10.1172/JCI30634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kakkar R, Lee RT. The IL-33/ST2 pathway: therapeutic target and novel biomarker. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:827–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimpo M, Morrow DA, Weinberg EO et al. Serum levels of the interleukin-1 receptor family member ST2 predict mortality and clinical outcome in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:2186–90. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127958.21003.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinberg EO, Shimpo M, Hurwitz S et al. Identification of serum soluble ST2 receptor as a novel heart failure biomarker. Circulation. 2003;107:721–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000047274.66749.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Januzzi JL, Peacock WF, Maisel AS et al. Measurement of the interleukin family member ST2 in patients with acute dyspnea: results from the PRIDE (Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:607–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Packer M, Carson P, Elkayam U et al. Effect of amlodipine on the survival of patients with severe chronic heart failure due to a nonischemic cardiomyopathy: results of the PRAISE-2 study (Prospective Randomized Amlodipine Survival Evaluation 2) JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:308–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Januzzi JL, Camargo CA, Anwaruddin S et al. The N-terminal Pro-BNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency department (PRIDE) study. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:948–54. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felker GM, Fiuzat M, Thompson V et al. Soluble ST2 in ambulatory patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:1172–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anand IS, Rector TS, Kuskowski M et al. Prognostic value of soluble ST2 in the valsartan heart failure trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:418–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ky B, French B, Levy WC et al. Multiple biomarkers for risk prediction in chronic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:183–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.965020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Broch K, Ueland T, Nymo SH et al. Soluble ST2 is associated with adverse outcome in patients with heart failure of ischaemic aetiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:268–77. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maisel AS, Di Somma S. Do we need another heart failure biomarker: focus on soluble suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (sST2) Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2325–33. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. Circulation. 2017;136:e137–61. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu J, Snider JV, Grenache DG. Establishment of reference intervals for soluble ST2 from a United States population. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1825–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dieplinger B, Januzzi JL, Steinmair M et al. Analytical and clinical evaluation of a novel high-sensitivity assay for measurement of soluble ST2 in human plasma – the Presage™ ST2 assay. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;409:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mueller T, Dieplinger B. Soluble ST2 and galectin-3: What we know and don’t know analytically. EJIFCC. 2016;27:224–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coglianese EE, Larson MG, Vasan RS et al. Distribution and clinical correlates of the interleukin receptor family member soluble ST2 in the Framingham Heart Study. Clin Chem. 2012;58:1673–81. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.192153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rech M, Barandiarán Aizpurua A, van Empel V et al. Pathophysiological understanding of HFpEF: microRNAs as part of the puzzle. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:782–93. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah SJ, Lam CSP, Svedlund S et al. Prevalence and correlates of coronary microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: PROMIS-HFpEF. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3439–50. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Heerebeek L, Borbély A, Niessen HWM et al. Myocardial structure and function differ in systolic and diastolic heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1966–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.587519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohammed SF, Hussain S, Mirzoyev SA et al. Coronary microvascular rarefaction and myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2015;131:550–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shah KB, Kop WJ, Christenson RH et al. Prognostic utility of ST2 in patients with acute dyspnea and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Clin Chem. 2011;57:874–82. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.159277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manzano-Fernández S, Mueller T, Pascual-Figal D et al. Usefulness of soluble concentrations of interleukin family member ST2 as predictor of mortality in patients with acutely decompensated heart failure relative to left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:259–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanders-van Wijk S, van Empel V, Davarzani N et al. Circulating biomarkers of distinct pathophysiological pathways in heart failure with preserved vs. reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:1006–14. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Najjar E, Faxén UL, Hage C et al. ST2 in heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2019;53:21–7. doi: 10.1080/14017431.2019.1583363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugano A, Seo Y, Ishizu T et al. Soluble ST2 and brain natriuretic peptide predict different mode of death in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Cardiol. 2019;73:326–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friões F, Lourenço P, Laszczynska O et al. Prognostic value of sST2 added to BNP in acute heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015;104:491–9. doi: 10.1007/s00392-015-0811-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moliner P, Lupón J, Barallat J et al. Bio-profiling and bio- prognostication of chronic heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol. 2018;257:188–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.01.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zile MR, Jhund PS, Baicu CF et al. Plasma biomarkers reflecting profibrotic processes in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction: data from the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ARB on Management of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction study. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e002551. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.AbouEzzeddine OF, McKie PM, Dunlay SM et al. Suppression of tumorigenicity 2 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004382. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA et al. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1268–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brunner M, Krenn C, Roth G et al. Increased levels of soluble ST2 protein and IgG1 production in patients with sepsis and trauma. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1468–73. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oshikawa K, Kuroiwa K, Tago K et al. Elevated soluble ST2 protein levels in sera of patients with asthma with an acute exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:277–81. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.2.2008120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagy AI, Hage C, Merkely B et al. Left atrial rather than left ventricular impaired mechanics are associated with the pro- fibrotic ST2 marker and outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Intern Med. 2018;283:380–91. doi: 10.1111/joim.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gaggin HK, Motiwala S, Bhardwaj A et al. Soluble concentrations of the interleukin receptor family member ST2 and β-blocker therapy in chronic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:1206–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maisel A, Xue Y, van Veldhuisen DJ et al. Effect of spironolactone on 30-day death and heart failure rehospitalization (from the COACH Study) Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:737–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martínez-Martínez E, Cachofeiro V, Rousseau E et al. Interleukin-33/ST2 system attenuates aldosterone-induced adipogenesis and inflammation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;411:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]