Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review summarizes recent literature for applying pharmacogenomics to antifungal selection and dosing, providing an approach to implementing antifungal pharmacogenomics in clinical practice.

Recent Findings

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium published guidelines on CYP2C19 and voriconazole, with recommendations to use alternative antifungals or adjust voriconazole dose with close therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). Recent studies demonstrate an association between CYP2C19 phenotype and voriconazole levels, clinical outcomes, and adverse events. Additionally, CYP2C19-guided preemptive dose adjustment demonstrated benefit in two prospective studies for prophylaxis. Pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic modeling studies have generated proposed voriconazole treatment doses based on CYP2C19 phenotypes, with further validation studies needed.

Summary

Sufficient evidence is available for implementing CYP2C19-guided voriconazole selection and dosing among select patients at risk for invasive fungal infections. The institution needs appropriate infrastructure for pharmacogenomic testing, integration of results in the clinical decision process, with TDM confirmation of goal trough achievement, to integrate antifungal pharmacogenomics into routine clinical care.

Keywords: Invasive fungal disease, Antifungal, Pharmacogenomics, Dosing, Voriconazole, CYP2C19

Introduction

Invasive fungal infections (IFI) are important, life-threatening conditions. Although rare in immunocompetent hosts outside the intensive care unit, incidence is rising with growing number of patients on immunosuppressive therapies, institutional exposures, and procedures. Recent estimates place overall incidence at 27.2 cases per 100,000 patient years, increasing about 1% per year [1]. Invasive candidiasis accounted for 55% of cases, followed by dimorphic fungi (25.2%), Aspergillus spp. (8.9%), Cryptococcus spp. and other yeast-like fungi (2.6%), other hyaline or dematiaceous molds (1.5%), and Mucorales (1.1%) [1]. Mortality from IFIs remains high, with combined 1-year all-cause mortality at 28.8%, with Mucorales being highest at 41.7%. Despite the growing number of IFIs, there remains a limited arsenal of effective treatments to manage these infections. It is thus important to understand the pharmacology of these agents to provide optimal antifungal selection, dosing, and monitoring. A key determinant to appropriate dosing is identifying clinical and genetic predictors of drug under- or over-exposure that can result in a loss of drug efficacy or increased toxicity. Following completion of the human genome project, there has been an interest to utilize pharmacogenomics, which studies how genetic variation influences drug response, to guide drug selection, and optimize dosing [2]. The purposes of this article are to (i) assess the literature for information on applying pharmacogenomics to antifungal selection and dosing, (ii) evaluate recent literature on pharmacogenomic-guided dosing using voriconazole as an example, and (iii) provide a pragmatic approach to implementing antifungal pharmacogenomics in clinical practice.

Antifungal—Pharmacology

The antifungal armamentarium includes six classes of drugs: azoles, echinocandins, polyenes, pyrimidine analogues, allylamines, and mitotic inhibitor [3]. Among which, the azoles are subject to cytochrome P450 (CYP450) biotransformation and subsequent pharmacogenomic influence with the most notable being voriconazole. Therefore, this review will focus on azoles (Table 1). The azoles exert their mechanism of activity through inhibiting 14α-demethylase, a CYP450-dependent enzyme, thereby preventing ergosterol formation. Their PK parameters vary with fluconazole, voriconazole, and isavuconazonium sulfate displaying excellent oral bioavailability, whereas posaconazole and itraconazole display more erratic oral absorption, though this has been improved with the newer formulations [12, 9]. With the exception of fluconazole, which is mainly eliminated unchanged renally, the other azoles undergo significant hepatic metabolism mostly via CYP450 enzymes. The CYP450 enzymes involved (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19) exhibit genetic polymorphisms, but the pharmacogenomic implications on the disposition of azoles currently appear to be minimal or are unknown with the exception of voriconazole [14••]. Despite its excellent oral absorption, voriconazole displays significant inter-patient variability with CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms accounting for 39% of the dose variability [15] and factors, such as CYP3A4, age, and body mass index accounting for 40% of the remaining dose variability [16] To circumvent absorption issues associated with posaconazole oral suspension and itraconazole, and genetic variability with voriconazole, therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is encouraged routinely for these three agents [4]. In reviewing the available antifungal pharmacology, voriconazole is presently the only agent with significant pharmacogenomic implications with dosing based upon CYP2C19 polymorphisms [15, 17••, 18].

Table 1.

Azole antifungal characteristics

| Medication | Usual dosing | Metabolism | Interactions | PGx potential | PK-PD and TDM [3, 4, 5, 6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketoconazole [7] | PO: 200–400 mg daily | Hepatic via CYP3A4 | Inhibits CYP3A4 (strong) and PgP (strong) | None expected | AUC/MIC > 25 TDM not indicated |

| Fluconazole [8] | Loading dose: 800–1200 mg IV or PO once Maintenance dose: 200–400 mg IV/PO once daily |

Minimal hepatic metabolism via CYP3A4, mostly eliminated unchanged via urine | Inhibits CYP3A4 and 2C9 (moderate) | Potential for impact on CYP2C9 substrates | AUC/MIC > 25 TDM not indicated |

| Itraconazolea [9, 10] | Loading dose: usual dose depending on formulation three times daily for first 3 days. Maintenance dose:

|

Hepatic via CYP3A4 | Inhibits CYP3A4 (strong), 2C9 (weak), and PgP | Potential for impact on CYP2C9 substrates | AUC/MIC > 25 TDM Goal Tr > 0.5–1 mg/L |

| Voriconazole [11] | Loading dose: 6 mg/kg IV or 400 mg PO q12h for 2 doses Maintenance dose:

|

Hepatic via CYP2C19 (major) and CYP2C9/3A4 (minor) | Inhibits CYP2C19 (strong) and 2C9/3A4 (moderate) | Yes, CYP2C19 | AUC/MIC > 25 TDM Goal Tr 1–5 mg/L |

| Posaconazoleb [12] | DR Tab/IV: 300 mg twice daily for 2 doses, then 300 mg once daily PO Soln: 200 mg four times daily or 400 mg twice daily |

Hepatic via glucuronidation (UGT1A4) | Inhibits CYP3A4 (strong) | None expected | AUC/MIC > 25 TDM Goal Tr > 0.7–1 mg/L |

| Isavuconazonium sulfate [13] | Loading dose:372 mg IV/PO every 8 h for 6 doses Maintenance dose: 372 mg IV/PO once daily |

Hepatic via CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and UGT | Inhibits: CYP3A4 (moderate), OCT2 Induces: CYP2B6 (weak) |

None expected | AUC/MIC > 25 TDM not indicated |

PGx, pharmacogenomics; PK–PD, pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic targets; TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring; PO, oral; IV, intravenous; Suba-, suba-itraconazole (Tolsura); PgP, P-glycoprotein; DR, delayed release; AUC, area under the curve; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; Tr, trough

Capsules 55% bioavailable (absorption best with food/acidic beverage), Solution bioavailability 70–80% in fasted state, Suba showed bioavailability of 175% vs. conventional capsule (improved in fasted and low gastric acidity conditions)

Oral suspension 8–47%, increased with high-fat meals, acidic beverages, and administration in small, divided doses (200 mg four times daily vs. 400 mg twice daily); delayed release tabs

Antifungal—Pharmacogenomic Implications

The Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB) is a National Institute of Health (NIH) funded online resource that provides curated pharmacogenomic information for various drugs, genes, genetic variants, and phenotypes [18, 19]. The NIH and PharmGKB created a Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) to provide peer-reviewed evidence-based guidelines to help clinicians apply available pharmacogenomic results to optimize drug therapy [20]. To date, CPIC has published 23 guidelines for 46 drugs across different therapeutic areas. Among which, CPIC published CYP2C19 and voriconazole guidelines that provide clinical recommendations on whether to use voriconazole or alternative antifungal agents based on CYP2C19 metabolizer phenotype [17••]. Given the limited antifungal armamentarium, there will be situations where voriconazole remains the antifungal of choice. As such, clinicians need to know if there is evidence to support CYP2C19-guided voriconazole dosing. The remainder of this review will focus on this evidence.

Voriconazole

Pharmacokinetics (PK) and Pharmacodynamics (PD) of Voriconazole

Voriconazole is used in the treatment and prophylaxis against various fungi, with the treatment dose comprised of a loading dose (6 mg/kg intravenously (IV) or 400 mg orally (PO) every 12 h for 2 doses) followed by a maintenance dosing (4 mg/kg IV or 200 mg PO every 12 h) [11]. The recommended prophylactic dose is 200 mg given twice daily [21]. Voriconazole exhibits non-linear pharmacokinetics [21] due to its saturable hepatic metabolism which is mainly via CYP2C19 and to a lesser extent via CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, to form inactive metabolites [22•]. It displays high inter- and intra-patient variability, with plasma levels influenced by factors such as age, sex, body weight, CYP2C19 polymorphism, inflammation, and drug–drug interactions [23]. Due to its saturable metabolism, PK variability, and narrow therapeutic index of 1–5.5 mg/L, routine TDM is recommended [4]. The PD goals reported are AUC:MIC ≥ 25 (preclinical) and Ctrough:MIC > 2 (clinical) with higher target troughs of 2–5 mg/L necessary in certain indications such as invasive aspergillosis, ocular, or central nervous system (CNS) infections [4, 24].

Voriconazole toxicities include neurologic (agitation, confusion, anxiety, tremor, auditory, and visual hallucination) and hepatobiliary effects which have been most correlated to troughs > 5–5.5 mg/L [4]. Additionally, skin disorders (rash, pruritis, photosensitivity, squamous cell carcinoma) and bone disorders (periostitis) have been reported, which are not directly related to voriconazole troughs and thus not likely related to pharmacogenomic influence, but duration of exposure [25].

CYP2C19 Polymorphism and Voriconazole Pharmacogenomics

There are more than 30 known CYP2C19 star (*) alleles with the majority of the population carrying CYP2C19*1, *2, *3, or *17 alleles. The wild-type *1 allele encodes normal CYP2C19 function, while *2 and *3 are the most common no function alleles, and*17 is an increased function allele. CYP2C19 polymorphisms result in five metabolizer phenotypes: ultrarapid (UM) (*17/*17), rapid (RM) (*1/*17), normal (NM) (*1/*1), intermediate (IM) (*1/*2, *1/*3, *2/*17), and poor metabolizer (PM) (*2/*2, *3/*3, *2/*3). The frequency of these phenotypes varies with race ethnicity, with CYP2C19 RM (ranging 16–27%) and IM (ranging 27–46%) being the common CYP2C19 polymorphisms [17••].

The CPIC voriconazole guidelines have separate adult and pediatric recommendations for voriconazole used in treatment doses stratified by CYP2C19 metabolizer status. This article will focus on adult recommendations. For CYP2C19 UM and RM, alternative antifungal agents such as isavuconazonium, liposomal amphotericin-B, or posaconazole are recommended to avoid the risk for therapeutic failure from subtherapeutic voriconazole levels. Among CYP2C19 NM and IM, standard voriconazole starting doses are recommended. For CYP2C19 PM, CPIC recommends using alternative antifungal agents or reducing voriconazole dose to avoid toxicity from supratherapeutic levels [17••]. All dosing recommendations are accompanied by TDM to guide subsequent dose adjustments to ultimately achieve therapeutic levels.

A 2015 review on the pharmacogenomics of voriconazole reported a relationship between CY2C19 genotype and voriconazole PK in healthy volunteers [26]. This association was less distinct among patients, and the authors concluded that additional studies were needed before CYP2C19 genotyping for voriconazole was routinely implemented. Since then, subsequent studies have demonstrated an association between CYP2C19 genotype and voriconazole PK, CYP2C19 genotype and voriconazole-related clinical and safety outcomes, PK-PD modeling studies, as well as prospective studies evaluating CYP2C19-guided dosing versus usual care on voriconazole levels and outcomes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies (from 2015 to 2019) on the relationship between CYP2C19 polymorphisms and voriconazole pharmacokinetics, clinical outcomes and adverse effects

| Study design, author, year | Age, race, sample size (n) | Treatment or prophylaxis use, voriconazole dose reported | CYP2C19 genotype (n) | Voriconazole PK, clinical outcomes and adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association between CYP2C19 genotype and voriconazole PK | ||||

| Case series, Weigel 2015 [27] | Adult Caucasian, n = 17 |

Treatment of critically ill adults 6 mg/kg IV q12h for first 24 h, then 4 mg/kg IV q12h |

UM/RM (n = 3) NM (n = 3) Unknown (n = 11) |

Subtherapeutic troughs occurred more frequently in UM/RM (77%) than NM (33%). |

| Retrospective study, Gautier-Veyret 2015 [28] | Adult Caucasian, n = 33 |

Prophylaxis, post-allogeneic HSCT No dose reported. |

UM/RM (n = 11) NM (n = 10) IM (n = 8) |

IM had higher initial trough levels than UM/RM (p <0.01) |

| Retrospective study, Lamoureux 2016 [29] | Adult Caucasian n = 35 genotyped n = 30 controls |

Treatment 400 mg PO q12H for first 24 h, then 200 mg PO q12H. Adjust by 50–100 mg q12H with goal trough 1–5 mg/L |

UM (n = 4) RM (n = 13) NM (n = 11) IM (n = 6) PM (n = 1) |

UM/RM associated with subtherapeutic levels PM associated with supratherapeutic levels |

| Case report, Hicks 2016 [30] | Pediatric (10 years old) Caucasian, n = 1 |

Treatment 9.5 mg/kg q12H then 8 mg/kg q12H |

RM (n = 1) | Pediatric RM patient whose final dose that achieved target trough was 14 mg/kg q12H for first 24 h then 12 mg/kg IV q12H |

| Prospective observational study, Chuwongwattana 2016 [31] | Adult Asian, n = 115 |

Treatment 6 mg/kg IV q12H then 4 mg/kg IV q12H or 200–250 mg PO BID |

NM (n = 59) IM (n = 42) PM (n = 14) |

IM and PM had higher trough levels than NM |

| Retrospective study, Niioka 2017 [32] | Adult Asian n = 65 |

Prophylaxis (n = 54) and treatment (n = 11), Dose ranged from 100 to 300 mg IV/PO BID | NM (n = 24) IM (n = 29) PM (n = 12) |

Subtherapeutic levels occurred more frequently in NM (58%), IM (21%), than PM (8%). Voriconazole to metabolite ratio was impacted by route of administration, C-reactive protein, age, and CYP2C19 genotype. |

| Prospective cohort study, Hamadeh 2017 [33] | Adults 81% Caucasian n = 70 |

Treatment 6 mg/kg IV q12H × first 24 h, then 4 mg/kg q12H. |

UM (n = 3) RM (n = 24) NM (n = 28) IM (n = 14) PM (n = 1) |

Subtherapeutic levels occurred more frequently in UM/RM (52%) than NM/IM/PM (16%) (p <0.01). Two UM and one RM achieved target level after dose increased to 5 mg/kg q12h. |

| Cross-sectional study, Ebrahimpour 2017 [34] | Adult Iranian n = 37 |

Treatment 400 mg IV BID × first 24 h then 200 mg IV/PO BID. Target level: 1–5.5 mg/L |

RM (n = 8) NM (n = 18) IM (n = 9) PM (n = 2) |

Genotype correlated with trough levels. RM: 25% at target level, 75% subtherapeutic level NM: 94% at target level, 6% supratherapeutic level IM: 78% at target level, 22% supratherapeutic level PM: 50% at target level, 50% supratherapeutic level |

| Retrospective study, You 2018 [35] | Adult Asian n = 64 |

Treatment IV or oral voriconazole per package insert |

NM (n = 29) IM (n = 27) PM (n = 8) |

PM had higher odds of supratherapeutic troughs than non-PM (p < 0.02). Variables that influenced troughs include age, CYP2C19 genotype, and liver function. |

| Retrospective cohort study, Miao 2018 [36] | Adult Asian n = 106 |

Treatment 400 mg q12H for 1st 24 h then 200 mg BID |

NM (n = 48) IM (n = 44) PM (n = 14) |

Median troughs were higher in PM, IM than NM (4.22, 3.12, and 1.87 mg/L respectively (p < 0.05) |

| Retrospective study, Shao 2017 [10] | Pediatric (≥ 15 years old) and adult Asian n = 86 |

Treatment or prophylaxis in hematological malignancy patients Dose per label with maintenance dose range from 200 to 600 mg daily. Target level: 1–4 mg/L |

NM (n = 32) IM (n = 36) PM (n = 18) |

IM/PM had higher troughs than NM (4.1 ± 2.5 vs. 2.8 ±1.9 mg/L) (p = 0.002) Additional variables for IM/PM included CYP3A4, age, and body mass index |

| Association between CYP2C19 genotype and voriconazole-related clinical and safety outcomes | ||||

| Retrospective study, Wang 2014 [37] | Adult Asian n = 144 |

Treatment Voriconazole dosed based on package insert |

RM (n = 3) NM (n = 62) IM (n = 62) PM (n = 17) |

Levels and clinical outcomes and safety: Trough levels correlated with efficacy and hepatoxicity. CYP2C19 genotype correlated with trough levels No association between CYP2C19 genotype and hepatotoxicity Response to treatment was ~ 90% when trough was 1.5–4 mg/L |

| Prospective study, Trubiano 2015 [38] | Adult Caucasian n = 19 |

Treatment, hematological malignancy patients, 6 mg/kg IV q12h × first 24 h then 4 mg/kg IV/PO q12h. | UM (n = 1) RM (n = 5) NM (n = 8) IM (n = 5) |

Trough correlated with CYP2C19 phenotype. Median trough higher in IM, NM followed by UM/RM (5.23, 3.3, and 1.25 mg/L respectively) UM/RM/NM (50%) had subtherapeutic levels. IM took longest time to reach target level. Adverse events was highest in IM (60%) and was mainly associated with hepatotoxicity or photopsia |

| Case reports, Beata 2017 [39] | Adult Caucasian n = 4 |

Prophylaxis, post-allogeneic-HSCT patients who developed adverse drug reaction so genotyping was done Dose was based on product label. |

IM (n = 4) | No voriconazole levels drawn Adverse events: GI, dermatological, neurological, hepatobiliary, and renal adverse reactions reported in these IM cases. |

| Case report, Danion 2018 [40] | Adult Caucasian n = 2 |

Treatment of cerebral aspergillus UM case: initially 200 mg BID RM case: initially 250 mg BID (4 mg/kg BID). Target trough: 2–5 mg/L |

UM (n = 1) RM (n = 1) |

UM: subtherapeutic troughs despite increasing dose to 350 mg BID (8 mg/kg BID). After genotyping showed UM phenotype, the drug was changed to isavuconazole with a treatment response. RM: subtherapeutic troughs and eventually increased to 400 mg PO TID (7 mg/kg TID) to reach target trough. Patient responded to treatment. |

| Application of PK-PD modeling to CYP2C19 genotype based voriconazole dose adjustments | ||||

| Retrospective study, Wang 2014 [37] | Adult Asian n = 144 |

Treatment Voriconazole dosed based on package insert |

RM (n = 3) NM (n = 62) IM (n = 62) PM (n = 17) |

Simulated-derived treatment voriconazole dose showed: For PM: 200 mg PO/IV BID For non-PM: 300 mg PO BD or 200 mg IV BID |

| Retrospective study, Lamoureux 2016 [29] | Adult Caucasian n = 35genotyped n = 30 controls |

Treatment 400 mg PO q12H for first 24 h, then 200 mg PO q12H. Adjust by 50–100 mg q12H with goal trough 1–5 mg/L |

UM (n = 4) RM (n = 13) NM (n = 11) IM (n = 6) PM (n = 1) |

UM/RM associated with subtherapeutic levels PM associated with supratherapeutic levels Model-derived oral dose: For UM: 6 mg/kg BID For RM: 4 mg/kg BID For NM: 2.5 mg/kg BID |

| Retrospective study, Mangal 2018 [24] | Adult 81% Caucasian n = 68 |

Treatment PK data from infected adults with known 2C19 genotypes receiving weight-based voriconazole dosing. Monte Carlo simulations performed to determine probability to achieve therapeutic level and response |

UM (n = 3) RM (n = 24) NM (n = 27) IM (n = 14) |

RM/UM had low probability to achieve therapeutic level for aspergillosis (trough > 2 mg/L) using 200 mg q12h (23.2%), improved by pantoprazole coadministration (46.5%). RM/UM: Monte Carlo simulation found labeled dosing appropriate for candidiasis, but higher dosing of 500–600 mg q12h needed for invasive aspergillus infections. Simulation generated different voriconazole doses in the presence and absence of different proton-pump inhibitors. |

| Prospective PK study, Lin 2018 [41] |

Adult Asian n = 106 |

Treatment or prophylaxis in renal transplant patients Voriconazole dose based on package insert. |

RM (n = 1) NM (n = 44) IM (n = 49) PM (n = 12) |

Trough correlated with CYP2C19 phenotype Median troughs in RM, NM, IM and PM were 1.90, 2.19, 2.32, and 3.86 mg/L (p < 0.001) Model-derived doses with target level 2–6 mg/L NM: 300 mg IV q12H IM: 200 mg IV q12H or 350 mg PO BID PM: 150 mg IV q12H or 250 mg PO BID. |

| Prospective PK study, Kim 2019 [42] | Adult Asian n = 193 (93 volunteers and 100 patients) |

Healthy volunteers and non-infected patients using different dosing regimens. Dose ranged from 200 to 400 mg IV or PO, as single or multiple doses every 12 h; to 6 mg/kg IV or oral 400 mg q12H for first 24 h, then 4 mg/kg or 200 mg PO q12H |

NM (n = 75) IM (n = 70) PM (n = 48) |

Voriconazole clearance was reduced in 17% (IM) and 53% (PM). Modeled dosing 400 mg q12h day 1,then 200 mg q12h predicted target troughs (2–5.5 mg/L) on day 7 in 39% (74% NM subtherapeutic and 48% PM supratherapeutic). Dose based on PK model: NM: 400 mg q12h IM: 200 mg q12h PM: 100 mg q12h |

| Prospective CYP2C19-guided voriconazole dosing | ||||

| Prospective study, Teusink 2016 [43] | Pediatric Race not reported Pilot group (n = 25) Genotype-guided group (n = 20) |

Prophylaxis, post-HCT patients Pilot study: fixed dose 5 mg/kg q12H Genotype-guided dosing NM: 7 mg/kg q12H IM: 6 mg/kg q12H PM: 5 mg/kg q12H Target level: 1–5.5 mg/L |

Pilot study RM (n = 2) NM (n = 17) IM (n = 3) PM (n = 1) Unknown (n = 1) Genotype-guided RM (n = 1) NM (n = 10) IM (n = 7) PM (n = 2) Unknown (n = 2) |

Median time to target level was shorter in IM, than NM and RM (4, 6.5, and 9 days respectively) Genotype-guided dosing reached target level faster (6.5 vs. 29 days, P < 0.01) when all patients were started on the same dose regardless of CYP2C19 genotype. |

| Case reports prospective genotyping, Fulco 2019 [44] | Adult n = 2 Caucasian (50%) AA (50%) |

Treatment, aspergillosis in HIV patients Genotype-guided initial dose adjustment NM: initial 200 mg BID IM: initial 350 mg BID with dose-adjusted per TDM. |

NM (n = 1) IM (n = 1) |

NM: final dose remained at 200 mg BID with TDM IM: final dose adjusted to 75 mg BID with TDM Preemptive genotyping guided initial voriconazole dose adjustment as there would be interaction with HIV medication (CYP3A4 inhibitor) that could explain the increased trough levels. |

| Prospective study, Patel 2019 [45•] | Adult n = 89 Caucasian (73%) |

Prophylaxis, post-allogeneic HCT UM/RM: 300 mg PO BID (intervention dose) NM/IM/PM: 200 mg PO BID (standard dose) |

UM (n = 3) RM (n = 29) NM (n = 30) IM (n = 23) PM (n = 4) |

Less patients with subtherapeutic levels in genotype-guided cohort than historical control (29% vs. 50%, p < 0.001) Lower subtherapeutic rates in UM/RM on intervention dose (15.6%) than NM and IM on standard dose (50% and 26.1% respectively). PM had no subtherapeutic rates (0%) at standard dose. The supratherapeutic rates in UM/RM on intervention dose was (6.3%) compared to NM/IM/PM (0%). Clinical success defined as no treatment failure or continued treatment until day 100 post-HCT showed higher success rate in genotype-guided vs. historical cohort group (78% vs. 54%, p < 0.001) Adverse events (56% transaminitis, 8% neurological symptoms) did not correlate with trough levels, with PM (33%), IM (17%), NM (13%), and UM/RM (14%). |

| Prospective study, Hicks 2019 [46•] | Adult n = 202 76% Caucasian |

Prophylaxis, acute myeloid leukemia patients UM: use alternative agent RM: 300 mg BID (intervention dose) NM/IM/PM: 200 mg BID (standard dose) |

176 patients dosed per protocol UM (n = 3) RM (n = 46) NM (n = 64) IM (n = 56) PM (n = 7) |

RM: median trough was higher with intervention vs standard dose (2.7 vs. 0.6 mg/L, p = 0.001) More RM achieved target level via CYP2C19-guided dosing than standard dosing (84% vs. 46%, p = 0.02) Clinical outcome: non-significant decrease in hospital-acquired nodular pneumonia incidence (p = 0.46) Adverse events: no difference in neurotoxicity or transaminitis rates between intervention and standard dosing groups. |

UM, ultrarapid metabolizer (CYP2C19*17/*17); RM, rapid metabolizer (CYP2C19*1/*17); NM, normal metabolizer (CYP2C19*1/*1); IM. intermediate metabolizer (CYP2C19*1/*2, *1/*3, *2/*17); PM. poor metabolizer (CYP2C19*2/*2, *2/*3, *3/*3); HCT, hematopoietic cell transplant; HIV human immunodeficiency virus; TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring

Association Between CYP2C19 Genotype and Voriconazole PK

Several studies have documented the relationship between CYP2C19 polymorphism on voriconazole PK in patients. Lamoureux et al. retrospectively evaluated 207 voriconazole levels from 67 patients initiated on voriconazole 200 mg orally twice daily for proven or suspected IFI [29]. The mean voriconazole trough was 2.5 ± 1.96 mg/L, with 37.7% subtherapeutic (< 1 mg/L) and 16.4% supratherapeutic (> 5 mg/L). Of these, 35 patients had genotyping results available with the phenotype analysis demonstrating UM/RM at significantly higher risk for subtherapeutic troughs versus NM (P < 0.001), while PM were at higher risk for supratherapeutic levels (P = 0.006). The average doses needed to reach therapeutic levels were higher among RM and UM, being 3.94 ± 0.39 mg/kg and 6.75 ± 0.54 mg/kg every 12 h respectively compared with 2.57 ± 0.25 mg/kg among NM. As expected, voriconazole clearance, elimination rate constant, and half-life differed among UM/RM and PM compared to NM in the direction of metabolism function gain or loss, respectively. The authors, however, did not comment directly about the clinical outcomes or adverse events related to sub- or supratherapeutic troughs. Another study by Hamadeh et al. prospectively evaluated 70 patients on weight-based voriconazole dosing for treatment of IFI in whom trough levels and CYP2C19 results were available [33]. Similarly, there was significant variability in voriconazole exposure, with 30% of the troughs being subtherapeutic (< 2 mg/L) and 20% being supratherapeutic (> 6 mg/L). Troughs were lower for UM/RM (2.86 ± 2.3 mg/L) compared to other phenotypes (4.26 ± 2.2 mg/L, P = 0.0093). Weight and CYP2C19 UM/RM phenotype were independent predictors that remained significantly associated with subtherapeutic troughs after multivariate regression analysis. No adverse events were observed by the authors. Additional groups have identified similar associations with CYP2C19 phenotypes and voriconazole exposure as shown in Table 2.

Association Between CYP2C19 Genotype and Voriconazole-related Clinical and Safety Outcomes

It has been previously well described that voriconazole troughs correlate with clinical response, avoidance of breakthrough IFIs, and some adverse events [4, 23]. Therefore, knowledge of a patient’s CYP2C19 phenotype in advance of prescribing could inform clinicians about the likelihood of achieving therapeutic concentrations and better predict effectiveness and tolerability. Recently, two CNS aspergillosis cases were reported by Danion et al., involving CYP2C19 RM and UM phenotypes [40]. The RM patient achieved therapeutic levels after several dose increases with a clinical response. The UM patient, on the other hand, remained subtherapeutic despite dose adjustments and finally demonstrated treatment response after being switched to isavuconazole. Trubiano et al. conducted a prospective pilot study in 19 patients and found IM phenotypes were more likely to experience voriconazole side effects (photopsia and hepatotoxicity) which were most likely as a result of higher trough concentrations [38]. High troughs, however, are not consistently associated with hepatotoxicity as observed in a study by Wang et al., using a predominant Asian cohort with larger numbers of IM (n = 62) and PM (n = 17) [37]. This retrospective study identified a correlation between high troughs and hepatotoxicity, with high troughs observed in IM and PM phenotypes, but no relationship was observed between hepatotoxicity and CYP2C19 status. These studies highlighted the impact of phenotype on voriconazole exposure, and its potential influence on clinical and safety outcomes. It is therefore important to find alternative empiric voriconazole dosing strategies, accompanied by TDM, in the setting of known CYP2C19 phenotype.

Application of PK–PD Modeling to CYP2C19 Genotype-based Voriconazole Dose Adjustments

Several studies have performed PK–PD modeling to predict optimal initial voriconazole dosing when patient’s CYP2C19 phenotype was available in advance of voriconazole initiation. Using a population PK model derived from 35 patients receiving voriconazole for suspected or proven IFI in whom CYP2C19 phenotype results were available, Lamoureux et al. suggested initial dosing of 2.5, 4, and 6 mg/kg every 12 h for NM, RM, and UM respectively might increase the likelihood of initial therapeutic troughs (1–5 mg/L) [29]. Mangal et al. performed Monte Carlo simulations based on previously published voriconazole PK parameters in patients with different CYP2C19 phenotypes [24]. The PD targets used in their model were Ctrough,ss > 2 mg/L, AUC24/MIC ≥ 25, and Ctrough,ss/MIC > 2, and MIC distributions that included both Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. At 200 mg twice daily dosing, the probability of target attainment (PTA) using each of the above targets was ≥ 90% for MIC ≤ 0.12 mg/L in all phenotypes, effective for most candida organisms. The PTA for goal of Ctrough,ss > 2 mg/L were 46.5% and 23.2% among RM/UM with and without pantoprazole respectively, and 64.9% and 39.9% among NM/IM with and without pantoprazole respectively. The cumulative fraction of response (CFR) was reported to be ≥ 80% for most Candida spp., except C. krusei while it was 40–70% for Aspergillus spp. using 200 mg of an oral voriconazole dose. Increased voriconazole doses of 500–600 mg twice daily (400–450 mg with concurrent pantoprazole) improved the net benefit (combined CFR and safety) to 51–66% in the RM/UM phenotype against invasive aspergillosis. Another study utilizing PK–PD modeling based on PK from 1828 voriconazole samples among 193 adults (93 healthy volunteers and 100 patients) suggested initial maintenance dosing of 400 mg, 200 mg, and 100 mg twice daily for NM, IM, and PM phenotypes, respectively to achieve therapeutic voriconazole troughs (2–5.5 mg/L) [42]. Taken together, these studies have proposed alternative voriconazole dosing in setting of known CYP2C19 phenotype to improve the likelihood of achieving therapeutic troughs; however, validation of these doses in clinical settings are necessary.

Prospective CYP2C19-guided Voriconazole Prophylactic Dosing

Two prospective studies aimed to address alternative empiric prophylactic voriconazole dosing in the presence of UM/RM CYP2C19 phenotype [46•, 45•]. Patel et al. evaluated the impact of prospective CYP2C19-guided voriconazole prophylactic dosing in a cohort of adult allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients (HCT) with the therapeutic voriconazole goal of 1.0–5.5 mg/L [45•]. Voriconazole dosing was 200 mg twice daily for PM/IM/NM and 300 mg twice daily for UM/RM, with the proportion of patients who achieved therapeutic level compared against a historical non-genotyped cohort that received voriconazole 200 mg twice daily. Of the 89 genotyped patients evaluated, 29% had subtherapeutic troughs < 1 mg/L (6% UM/RM versus 23% PM/IM/NM) compared to 50% of historic controls (p < 0.001). Interestingly, 16% and 7% of NM and IM respectively were subtherapeutic. Voriconazole prophylaxis success (defined as less than 14 total days of interrupting voriconazole treatment due to voriconazole toxicity, absence of proven/probable IFI, or continued voriconazole treatment for at least 100 days post-HCT) was 78% in the genotype-guided group compared to 54% historically (p < 0.001). Overall, 41% of the genotyped cohort experienced adverse effects possibly related to voriconazole, which were not correlated with trough concentrations. Hicks et al. evaluated a prospective CYP2C19-guided voriconazole prophylactic dosing among 176 patients with acute myeloid leukemia [46•]. Similar to the Patel et al. study, voriconazole dosing was 300 mg twice for RM, but UM received alternative antifungal prophylaxis, while PM/IM/NM received voriconazole 200 mg twice daily. The median voriconazole trough was 2.7 mg/L versus 0.6 mg/L in RM who received voriconazole 300 mg twice daily versus those whose providers chose to keep on 200 mg twice daily (p = 0.001), with the proportion of RM with subtherapeutics troughs < 1 mg/L being 16.2% versus 53.8% (p = 0.02) respectively. There were no subtherapeutic IM or PM patients, but 31% NM were < 1 mg/L. The rate of hospital-acquired nodular pneumonia was slightly lower in the CYP2C19-guided cohort versus a historical non-genotyped cohort (2.1 vs. 2.2 cases per 1000 neutropenic days, p = 0.46). While these are important findings in the prospective application of CYP2C19-guided dosing, more studies are needed to validate the higher doses for treatment indications and to understand the reason behind the high subtherapeutic rates among NM.

Implementation of Antifungal Pharmacogenomics

The decision to incorporate antifungal pharmacogenomics into clinical practice involves considering factors such as identifying patients for genotyping, selecting a laboratory to perform the test, timing of the pharmacogenomic test, and translation of the results into prescribing decisions. Up-front knowledge of CYP2C19 genotype appears to be useful in guiding whether voriconazole is the appropriate treatment option and the empiric dose for certain CYP2C19 phenotypes.

Patient Selection for CYP2C19-Voriconazole Genotyping

Most insurance companies currently do not reimburse CYP2C19-voriconazole testing; therefore, providers have to be judicious in selecting patients for genotyping. Patient selection could be based on high-risk populations with a high likelihood of being prescribed voriconazole, such as hematologic malignancy, solid organ transplant (SOT), and pre-HCT patients. Important populations to exclude from genotyping would be post-liver transplant and post-allogeneic HCT recipients since the genotype from blood sample would not reflect the correct genetics.

Laboratory Selection for CYP2C19 Pharmacogenomic Testing

Selecting a reference laboratory for CYP2C19 testing depends on (i) whether genomic variants important for the target patient population are adequately tested and (ii) the turnaround time for the results. The Association for Molecular Pathology recently published the list of clinical CYP2C19 genetic variants to be included in clinical pharmacogenomic testing panels [47], and the NIH Genetic Testing Registry can be used to locate laboratories offering CYP2C19 testing for these clinically relevant variants [48]. Within the USA, the testing laboratory must meet federal regulatory standards, such as the College of American Pathologists and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA) certification, to certify that the reported results are robust enough for clinical use [49].

Timing of CYP2C19 Pharmacogenomic Testing

Ideally, patient’s CYP2C19 results should be available at the point of prescribing voriconazole to guide providers with antifungal drug and dose selection. This will require patient’s DNA sample to be obtained in advance for preemptive genotyping prior to voriconazole prescribing, or the result would need to have rapid turnaround time for clinical use. Given the potential value of using CYP2C19-guided dosing in highly selected patients, one could consider preemptively genotyping SOT or HCT patients while they are on the transplant waitlist.

Integration of CYP2C19 Results in Electronic Health Records to Guide Pharmacogenomic Decisions

The integration of pharmacogenomic results into the electronic health record is vital to facilitate the successful implementation of pharmacogenomics in routine clinical care [50, 51]. Clinical decision support (CDS) tools designed in the form of “pop-up” alerts could be used to inform providers when voriconazole is prescribed to patients with clinically actionable CYP2C19 phenotypes (UM, RM, and PM). Ideally, these CDS tools would include actionable features, such as links to prescribing alternative antifungal agents based on institution’s drug formulary or the option of using dose-adjusted voriconazole. In this way, CDS can streamline the clinical decision pathway and capture pertinent information needed for a clinical decision at the point of prescribing. Additionally, this CDS tool could alert to the institution’s Antimicrobial Stewardship Team (AST) to track and monitor these cases as part of their surveillance work [52].

UCHealth CYP2C19-Voriconazole Pharmacogenomic Implementation Experience

At the University of Colorado Health (UCHealth), pharmacogenomics is implemented at a system-wide level using a preemptive, panel-based testing approach for patients enrolled in our UCHealth Biobank. As genotyping is done in a CLIA certified laboratory, select pharmacogenomic results can be returned to the electronic health record of patients who consent to have their results returned for clinical use. The first gene deployed was CYP2C19, with CYP2C19-voriconazole pharmacogenomics recently implemented in the inpatient and outpatient setting. Prior to implementation, key stakeholders from services such as AST, SOT, and bone marrow transplant were approached with supporting evidence for voriconazole pharmacogenomic implementation. Their feedback was gathered to aid the integration of CYP2C19-guided voriconazole dosing into routine clinical care.

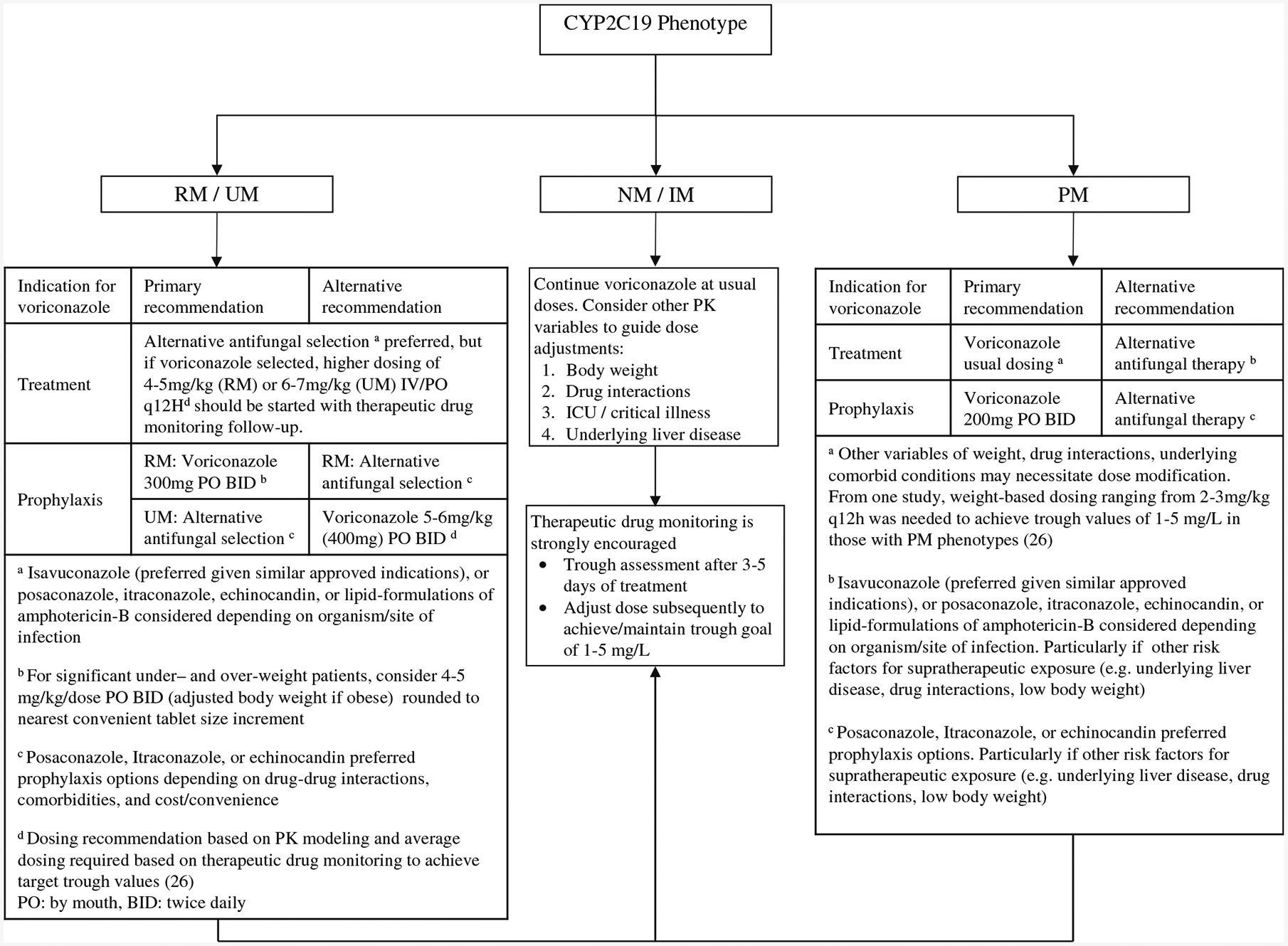

A CYP2C19-guided voriconazole dosing algorithm was developed in collaboration with the AST (Fig. 1). Based upon the evidence presented in this review and the CPIC guidelines, it is recommended that the UM/RM group consider using an alternative antifungal for treatment indications. However, it is important to note that under certain clinical situations voriconazole may remain indicated, so adjusted dosing recommendations are included based on the literature PK–PD modeling data. For prophylaxis, RM may require a higher voriconazole dose of 300 mg twice daily, while for UM alternative antifungal is preferred. It is important to be aware that higher voriconazole dosing to achieve therapeutic troughs among UM/RM phenotypes may have unintended consequences from exposure to higher fluoride (16.25 mg fluoride per 100 mg voriconazole) and N-oxide metabolite concentrations. For PM phenotypes, a decreased dose may be necessary in certain situations such as patients on concomitant QT prolonging medications or very low body weight individuals to avoid potential toxicity. NM and IM phenotypes are recommended to be initiated on standard dosing, although it is important to consider other potential influences for voriconazole exposure since CYP2C19 polymorphism accounts for 39% of the dose variability. Patients who had undergone allogeneic HCT or liver transplant should be excluded from this clinical algorithm due to the potential for genetic discordance.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for application of CYP2C19 phenotype with antifungal selection/dosing IM, intermediate metabolizer; NM, normal metabolizer; PM, poor metabolizer; RM, rapid metabolizer; UM, ultrarapid metabolizer; PK, pharmacokinetic

At UCHealth, institution-specific CDS tools were developed by the informatics team based on stakeholders’ feedback. An interruptive best practice advisory alert with a link to the algorithm is shown when providers prescribe voriconazole to patients with CYP2C19 RM, UM, or PM phenotypes. Providers would be prompted to indicate if voriconazole was prescribed for treatment or prophylactic purpose, and they could follow the algorithm to select an alternative antifungal or adjust voriconazole dose. In all cases, the algorithm states that pharmacogenomic-guided dosing must be considered in context of other factors such as patient’s body weight, drug-drug interaction (e.g., proton-pump inhibitor co-administration), using TDM to guide further dose adjustments and ultimately achieve therapeutic troughs.

Special Voriconazole Considerations Based on CYP2C19-Phenotype

Certain clinical indications such as ocular and CNS infections favor the use of voriconazole over other antifungal agents based on the larger body of evidence from historical studies and clinical experience. However, recent studies have reported good activity with the use of isavuconazonium sulfate in treating CNS infections [53, 54]. This provides an alternative agent especially in CYP2C19 UM/RM patients who would inherently require higher voriconazole doses to ensure sufficient drug penetrates those sites of infection, while weighing the risk of voriconazole toxicity. Additionally, one must consider the effects of long-term exposure to high-dose voriconazole in CYP2C19 UM/RM patients, as this may increase the risk of adverse events such as squamous cell carcinoma and periostitis [25]. It has been found that lung transplant recipients who are CYP2C19 UM/RM have a 74% increased hazard risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma [55]. This has been postulated to be due to the primary metabolite, voriconazole N-oxide, being a chromophore for UVB, and may be involved in DNA damage. Rapid metabolism of voriconazole to this metabolite in CYP2C19 UM/RM can result in higher metabolite concentrations and potentially predispose patients to squamous cell carcinoma. Another adverse effect is periostitis caused by high fluoride levels in voriconazole (65 mg fluoride per 400 mg voriconazole, 15 times the usual daily intake), that can result in skeletal pain [25]. This is exposure-dependent with high voriconazole levels resulting in higher plasma fluoride levels especially if a UM/RM patient requires increased doses; thus, voriconazole is either discontinued or dose-reduced.

Additionally, certain drug–drug interactions may become more significant among certain CYP2C19 phenotypes. Although voriconazole is metabolized mainly via CYP2C19 and to a lesser extent via CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, these minor pathways may be important in CYP2C19 PM. This was demonstrated in a cross-over PK study involving healthy volunteers given ritonavir-boosted atazanavir and voriconazole, to examine the drug–drug interaction in PM and non-PM subjects [56]. The study reported a 5.6-fold increase in voriconazole levels in PM subjects from CYP3A inhibition by atazanavir/ritonavir. This is in contrast to the 33% decrease in voriconazole levels in non-PM due to ritonavir-induced CYP2C19 metabolism. Therefore, clinical factors such as drug–drug interactions need to be taken into consideration and not just the CYP2C19 phenotype alone.

Evaluation of the Antifungal Pharmacogenomic Implementation Initiative

Several challenges have been identified with the clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics in practice, ranging from provider unfamiliarity with pharmacogenomics; cost of testing; and turnaround time of results, to integration of pharmacogenomic results within the prescribing process [57, 58]. These demonstrate the need for a systematic approach to implementing pharmacogenomics to ensure its successful adoption and sustainability over time [52]. Various performance metrics can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of an antifungal pharmacogenomic program, and these encompass different domains such as clinical outcomes (e.g., shorter time to target voriconazole levels, response to therapy, incidence of IFI breakthrough), safety outcomes (e.g., frequency of adverse events reported), and operational outcomes (e.g., number of CDS recommendations accepted by providers) [59]. It is vital to engage stakeholders early in the implementation process to identify outcomes of interest and determine if these are captured in the institution’s current infrastructure.

Future Directions

While two prospective studies have examined the role of CYP2C19-guided voriconazole dosing using prophylactic doses, modeling studies have demonstrated the need for increased doses to reach therapeutic target; hence, extrapolating this to treatment doses in UM/RM and PM needs to be validated before it can be widely accepted. Furthermore, studies are ongoing to identify additional biomarkers that can contribute toward voriconazole dose variability [60]. Some studies have found that severe inflammation could downregulate voriconazole metabolism resulting in higher drug exposure [61, 62]. These findings underscore the role of pharmacogenomics as a tool to be considered in addition to other factors (e.g., body weight, underlying liver disease) in determining the optimal antifungal selection and dosing, with TDM to complement dose titrations to achieve therapeutic troughs.

Conclusion

The current data for antifungal pharmacogenomics is strongest with CYP2C19-voriconazole, with CPIC guidelines available to guide voriconazole use based on CYP2C19 metabolizer phenotype. Genetic polymorphism with CYP2C19 has a significant influence on voriconazole levels, with evidence correlating CYP2C19 phenotype with voriconazole PK, clinical and safety outcomes. Recent CYP2C19-guided voriconazole prophylactic dosing studies have demonstrated the feasibility of implementing voriconazole pharmacogenomics with genotype-guided dosing achieving higher therapeutic rates. Various PK model simulations have generated voriconazole treatment doses based on CYP2C19 phenotypes, but need future validation. Nevertheless, there is sufficient evidence to support the adoption of CYP2C19-guided voriconazole dosing for select patient populations in conjunction with TDM. Additionally, institutions need the appropriate infrastructure that incorporates pharmacogenomic testing to make antifungal pharmacogenomics as part of routine clinical care.

Funding Information

Study authors are supported by the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CCTSI). The CCTSI is supported in part by Colorado CTSA Grant UL1TR001082 from NCATS/NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Matthew A. Miller reports personal fees from Allergan outside the submitted work. Yee Ming Lee reports personal fees from Dynamed Plus (EBSCO Health) outside the submitted work.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Webb BJ, Ferraro JP, Rea S, Kaufusi S, Goodman BE, Spalding J. Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Invasive Fungal Infection in a US health care network. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(8): ofy187 10.1093/ofid/ofy187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans WE, McLeod HL. Pharmacogenomics–drug disposition, drug targets, and side effects. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(6):538–49. 10.1056/NEJMra020526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis RE. Current concepts in antifungal pharmacology. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(8):805–17. 10.4065/mcp.2011.0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashbee HR, Barnes RA, Johnson EM, Richardson MD, Gorton R, Hope WW. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of antifungal agents: guidelines from the British Society for Medical Mycology. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(5):1162–76. 10.1093/jac/dkt508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buil JB, Bruggemann RJM, Wasmann RE, Zoll J, Meis JF, Melchers WJG, et al. Isavuconazole susceptibility of clinical Aspergillus fumigatus isolates and feasibility of isavuconazole dose escalation to treat isolates with elevated MICs. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(1):134–42. 10.1093/jac/dkx354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lepak AJ, Marchillo K, Vanhecker J, Andes DR. Isavuconazole (BAL4815) pharmacodynamic target determination in an in vivo murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis against wild-type and cyp51 mutant isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(12):6284–9. 10.1128/AAC.01355-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ketoconazole [package insert], Morgantown, WV: Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diflucan (Fluconazole) [package insert], NY, NY: Pfizer Inc,; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tolsura (itraconazole) [package insert]. Greenville, NC: Mayne Pharma Inc; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sporanox (itraconazole) [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vfend (voriconazole) [package insert]. NY, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Posaconazole [package insert]. Chestnut Ridge, NY: Par Pharmaceutical; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isavuconazonium sulfate [package insert], Northbrook, IL: Astellas Pharma US; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.••.Amsden JR, Gubbins PO. Pharmacogenomics of triazole antifungal agents: implications for safety, tolerability and efficacy. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13(11):1135–46. 10.1080/17425255.2017.1391213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A review of the impact of CYP450 enzymes on the different azoles.

- 15.Weiss J, Ten Hoevel MM, Burhenne J, Walter-Sack I, Hoffmann MM, Rengelshausen J, et al. CYP2C19 genotype is a major factor contributing to the highly variable pharmacokinetics of voriconazole. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49(2):196–204. 10.1177/0091270008327537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shao B, Ma Y, Li Q, Wang Y, Zhu Z, Zhao H, et al. Effects of cytochrome P450 3A4 and non-genetic factors on initial voriconazole serum trough concentrations in hematological patients with different cytochrome P450 2C19 genotypes. Xenobiotica. 2017;47(12):1121–9. 10.1080/00498254.2016.1271960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.••.Moriyama B, Obeng AO, Barbarino J, Penzak SR, Henning SA, Scott SA, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines for CYP2C19 and voriconazole therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102(1):45–51. Doi: 1002/cpt.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This shows the pharmacogenetic guidelines for CYP2C19-voriconazole.

- 18.PharmGKB [Available from: https://www.pharmgkb.org/].

- 19.Klein TE, Chang JT, Cho MK, Easton KL, Fergerson R, Hewett M, et al. Integrating genotype and phenotype information: an overview of the PharmGKB project. Pharmacogenetics Research Network and Knowledge Base. Pharm J. 2001;1(3):167–70. 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Relling MV, Klein TE, Gammal RS, Whirl-Carrillo M, Hoffman JM, Caudle KE. The clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium: 10 years later. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019. 10.1002/cpt.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, Gress R, Sepkowitz K, Storek J, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(10):1143–238. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.•.Barbarino JM, Owusu Obeng A, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB summary: voriconazole pathway, pharmacokinetics. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2017;27(5):201–9. 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The PharmGKB summary of voriconazole.

- 23.Owusu Obeng A, Egelund EF, Alsultan A, Peloquin CA, Johnson JA. CYP2C19 polymorphisms and therapeutic drug monitoring of voriconazole: are we ready for clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics? Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(7):703–18. 10.1002/phar.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangal N, Hamadeh IS, Arwood MJ, Cavallari LH, Samant TS, Klinker KP, et al. Optimization of voriconazole therapy for the treatment of invasive fungal infections in adults. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104(5):957–65. 10.1002/cpt.1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine MT, Chandrasekar PH. Adverse effects of voriconazole: over a decade of use. Clin Transpl. 2016;30(11):1377–86. 10.1111/ctr.12834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moriyama B, Kadri S, Henning SA, Danner RL, Walsh TJ, Penzak SR. Therapeutic drug monitoring and genotypic screening in the clinical use of voriconazole. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2015;9(2): 74–87. 10.1007/s12281-015-0219-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weigel JD, Hunfeld NG, Koch BC, Egal M, Bakker J, van Schaik RH, et al. Gain-of-function single nucleotide variants of the CYP2C19 gene (CYP2C19*17) can identify subtherapeutic voriconazole concentrations in critically ill patients: a case series. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(11):2013–4. 10.1007/s00134-015-4002-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gautier-Veyret E, Bailly S, Fonrose X, Tonini J, Chevalier S, Thiebaut-Bertrand A, et al. Pharmacogenetics may influence the impact of inflammation on voriconazole trough concentrations. Pharmacogenomics. 2017;18(12):1119–23. 10.2217/pgs-2017-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamoureux F, Duflot T, Woillard JB, Metsu D, Pereira T, Compagnon P, et al. Impact of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms on voriconazole dosing and exposure in adult patients with invasive fungal infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;47(2):124–31. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hicks JK, Gonzalez BE, Zembillas AS, Kusick K, Murthy S, Raja S, et al. Invasive Aspergillus infection requiring lobectomy in a CYP2C19 rapid metabolizer with subtherapeutic voriconazole concentrations. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17(7):663–7. 10.2217/pgs-2015-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chuwongwattana S, Jantararoungtong T, Chitasombat MN, Puangpetch A, Prommas S, Dilokpattanamongkol P, et al. A prospective observational study of CYP2C19 polymorphisms and voriconazole plasma level in adult Thai patients with invasive aspergillosis. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2016;31(2):117–22. 10.1016/j.dmpk.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niioka T, Fujishima N, Abumiya M, Yamashita T, Ubukawa K, Nara M, et al. Relationship between the CYP2C19 phenotype using the voriconazole-to-voriconazole N-oxide plasma concentration ratio and demographic and clinical characteristics of Japanese patients with different CYP2C19 genotypes. Ther Drug Monit. 2017;39(5): 514–21. 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamadeh IS, Klinker KP, Borgert SJ, Richards AI, Li W, Mangal N, et al. Impact of the CYP2C19 genotype on voriconazole exposure in adults with invasive fungal infections. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2017;27(5):190–6. 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebrahimpour S, Namazi S, Mohammadi M, Nikbakht M, Hadjibabaie M, Masoumi HT, et al. Impact of CYP2C19 polymorphisms on serum concentration of voriconazole in Iranian hematological patients. J Res Pharm Pract. 2017;6(3):151–7. 10.4103/jrpp.JRPP_17_31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.You H, Dong Y, Zou Y, Zhang T, Lei J, Chen L, et al. Voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring: factors associated with supratherapeutic and subtherapeutic voriconazole concentrations. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;56(5):239–46. 10.5414/CP203184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miao Q, Tang JT, van Gelder T, Li YM, Bai YJ, Zou YG, et al. Correlation of CYP2C19 genotype with plasma voriconazole exposure in South-western Chinese Han patients with invasive fungal infections. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(3):e14137 10.1097/MD.0000000000014137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang T, Zhu H, Sun J, Cheng X, Xie J, Dong H, et al. Efficacy and safety of voriconazole and CYP2C19 polymorphism for optimised dosage regimens in patients with invasive fungal infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;44(5):436–42. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trubiano JA, Crowe A, Worth LJ, Thursky KA, Slavin MA. Putting CYP2C19 genotyping to the test: utility of pharmacogenomic evaluation in a voriconazole-treated haematology cohort. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(4):1161–5. 10.1093/jac/dku529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beata S, Donata UK, Jaroslaw D, Tomasz W, Anna WH. Influence of CYP2C19*2/*17 genotype on adverse drug reactions of voriconazole in patients after allo-HSCT: a four-case report. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(6):1103–6. 10.1007/s00432-017-2357-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danion F, Jullien V, Rouzaud C, Abdel Fattah M, Lapusan S, Guery R, et al. Is it time for systematic voriconazole pharmacogenomic investigation for central nervous system aspergillosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(9). 10.1128/AAC.00705-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin XB, Li ZW, Yan M, Zhang BK, Liang W, Wang F, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of voriconazole and CYP2C19 polymorphisms for optimizing dosing regimens in renal transplant recipients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(7):1587–97. 10.1111/bcp.13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim Y, Rhee SJ, Park WB, Yu KS, Jang IJ, Lee S. A Personalized CYP2C19 phenotype-guided dosing regimen of voriconazole using a population pharmacokinetic analysis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(2). 10.3390/jcm8020227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teusink A, Vinks A, Zhang K, Davies S, Fukuda T, Lane A, et al. Genotype-directed dosing leads to optimized voriconazole levels in pediatric patients receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(3):482–6. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fulco PP, Beaulieu C, Higginson RT, Bearman G. Pharmacogenetic testing for the treatment of aspergillosis with voriconazole in two HIV-positive patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2019;29(6):155–7. 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.•.Patel JN, Hamadeh IS, Robinson M, Shahid Z, Symanowski J, Steuerwald N, et al. Evaluation of CYP2C19 genotype-guided voriconazole prophylaxis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019. 10.1002/cpt.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A prospective study comparing CYP2C19-guided versus standard voriconazole prophylactic dosing in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant patients.

- 46.•.Hicks JK, Quilitz RE, Komrokji RS, Kubal TE, Lancet JE, Pasikhova Y, et al. Prospective CYP2C19-guided voriconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenic acute myeloid leukemia reduces the incidence of subtherapeutic antifungal plasma concentrations. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019. 10.1002/cpt.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A prospective study comparing CYP2C19-guided versus standard voriconazole prophylactic dosing in acute myeloid leukemia patients.

- 47.Pratt VM, Del Tredici AL, Hachad H, Ji Y, Kalman LV, Scott SA, et al. Recommendations for clinical CYP2C19 genotyping allele selection: a report of the association for molecular pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2018;20(3):269–76. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rubinstein WS, Maglott DR, Lee JM, Kattman BL, Malheiro AJ, Ovetsky M, et al. The NIH genetic testing registry: a new, centralized database of genetic tests to enable access to comprehensive information and improve transparency. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D925–35. 10.1093/nar/gks1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vo TT, Bell GC, Owusu Obeng A, Hicks JK, Dunnenberger HM. Pharmacogenomics implementation: considerations for selecting a reference laboratory. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(9):1014–22. 10.1002/phar.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caraballo PJ, Bielinski SJ, St Sauver JL, Weinshilboum RM. Electronic medical record-integrated pharmacogenomics and related clinical decision support concepts. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102(2):254–64. 10.1002/cpt.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hicks JK, Dunnenberger HM, Gumpper KF, Haidar CE, Hoffman JM. Integrating pharmacogenomics into electronic health records with clinical decision support. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(23):1967–76. 10.2146/ajhp160030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klein ME, Parvez MM, Shin JG. Clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics for personalized precision medicine: barriers and solutions. J Pharm Sci. 2017;106(9):2368–79. 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rouzaud C, Jullien V, Herbrecht A, Palmier B, Lapusan S, Morgand M, et al. Isavuconazole diffusion in infected human brain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(10). 10.1128/AAC.02474-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwartz S, Cornely OA, Hamed K, Marty FM, Maertens J, Rahav G, et al. Isavuconazole for the treatment of patients with invasive fungal diseases involving the central nervous system. Med Mycol. 2019. 10.1093/mmy/myz103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams K, Arron ST. Association of CYP2C19 *17/*17 genotype with the risk of voriconazole-associated squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(6):719–20. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu L, Bruggemann RJ, Uy J, Colbers A, Hruska MW, Chung E, et al. CYP2C19 genotype-dependent pharmacokinetic drug interaction between voriconazole and ritonavir-boosted atazanavir in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57(2):235–46. 10.1002/jcph.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Owusu Obeng A, Fei K, Levy KD, Elsey AR, Pollin TI, Ramirez AH, et al. Physician-reported benefits and barriers to clinical implementation of genomic medicine: a multi-site IGNITE-network survey. J Pers Med. 2018;8(3). 10.3390/jpm8030024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sperber NR, Carpenter JS, Cavallari LH, Damschroder LJ, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Denny JC, et al. Challenges and strategies for implementing genomic services in diverse settings: experiences from the Implementing GeNomics In pracTicE (IGNITE) network. BMC Med Genet. 2017;10(1):35 Doi: 10.1186/s12920-017-0273-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luzum JA, Pakyz RE, Elsey AR, Haidar CE, Peterson JF, Whirl-Carrillo M, et al. The pharmacogenomics research network translational pharmacogenetics program: outcomes and metrics of pharmacogenetic implementations across diverse healthcare systems. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102(3):502–10. 10.1002/cpt.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dapia I, Garcia I, Martinez JC, Arias P, Guerra P, Diaz L, et al. Prediction models for voriconazole pharmacokinetics based on pharmacogenetics: an exploratory study in a Spanish population. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019;54(4):463–70. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shah RR, Smith RL. Inflammation-induced phenoconversion of polymorphic drug metabolizing enzymes: hypothesis with implications for personalized medicine. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43(3): 400–10. 10.1124/dmd.114.061093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Veringa A, Ter Avest M, Span LF, van den Heuvel ER, Touw DJ, Zijlstra JG, et al. Voriconazole metabolism is influenced by severe inflammation: a prospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(1):261–7. 10.1093/jac/dkw349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]