ABSTRACT

Background

Mutations in the STIP1 homology and U‐box containing protein 1 gene were first described in 2013 and lead to disorders with symptoms including ataxia and dysarthria, such as spinocerebellar autosomal‐recessive ataxia type 16 (SCAR16), Gordon‐Holmes syndrome, and spinocerebellar ataxia type 48. There have been 15 families described to date with SCAR16.

Cases

We describe a 45‐year‐old right‐handed woman with dysarthria, ataxia, and cervical dystonia with SCAR16 with 2 compound heterozygous variants in the STIP1 homology and U‐box containing protein 1 gene, and a family history significant for her 47‐year‐old sister with dysarthria and cognitive problems.

Conclusion

We present a comprehensive overview of the phenotypic data of all 15 families with SCAR16 and expand the phenotype by describing a third patient with SCAR16 and dystonia reported to date in the literature.

Keywords: STUB1, SCAR16, autosomal recessive ataxia type 16

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/page/journal/23301619/homepage/mdc312914-sup-v001.htm

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/page/journal/23301619/homepage/mdc312914-sup-v002.htm

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/page/journal/23301619/homepage/mdc312914-sup-v003.htm

Subacute‐onset cerebellar ataxia affecting siblings and skipping generations is suggestive of an autosomal‐recessive hereditary ataxia, including Friedreich's ataxia (ATX‐FXN), ataxia‐teleangiectasia (ATX‐ARL13B, ATX‐ATM), ataxia with oculomotor apraxia (AOA1 and AOA2; ATX‐APTX and ATX‐SETX), and autosomal‐recessive spinocerebellar ataxia (SCAR), especially after nongenetic causes of cerebellar degeneration have been ruled out.1

SCAR16 (ATX–STIP1 homology and U‐box containing protein 1 [STUB1]) is a rare condition described in a handful of families worldwide. It is caused by a homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the STUB1 gene on chromosome 16p13 encoding the carboxylate‐terminus of Hsc70 interacting (CHIP) protein (E3 ligase), essential in protein quality control of the ubiquitin proteasome system. Age at onset is variable and ranges from 2 to 57.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Phenotype varies and may include mild cognitive impairment, truncal and limb ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, nystagmus, pyramidal signs (lower limb spasticity), and peripheral sensory neuropathy (impaired position sense).2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Dystonia in SCAR16 (ATX‐STUB1) has been described in 1 case report to date.8

We report a patient of European descent with ataxia and cervical dystonia who harbored 2 heterozygous variants in the STUB1 gene. We expand the phenotypic spectrum associated with STUB1 mutations and present the comprehensive phenotypic summary of all known SCAR16 (ATX‐STUB1) carriers to date.

Case Series

Case 1

A 45‐year‐old right‐handed Irish woman reported a 6‐month history of dysarthria (no autonomic symptoms, cognitive symptoms, or dysphagia) and progressive ataxia without weakness. Initially independent, within 6 months from symptom onset she required a walking aid, and a year later a rollator. Within the first year she also developed cervical dystonia. Her early life, including pregnancy, birth, and development (school performance and social skills), was normal. The only past medical history was that of asthma for which she used salbutamol inhaler as needed. She was a nonsmoker and rarely drank alcohol (1 glass of wine/month). She had 3 sons aged 23, 17, and 13 years old, all of whom were asymptomatic.

Neurological examination of the proband (Fig. 1, III‐4) showed cerebellar dysarthria and ataxia. She dragged her right foot. There was an inward turning of the right foot present only while walking (Video S1; and not when sitting or lying down). She was unable to tandem walk or stand on 1 foot. Scale for assessment and rating of ataxia (SARA) score was 15/56 (gait, 6 points; stance, 1; sitting, 0; speech disturbance, 4; finger chase, 0; nose–finger test, L 1 and R 1; fast alternating movements, 0; heel shin slide, L 1 and R 1). Although the saccadic eye movements were normal, the pursuits were slow and mildly broken. There were no square wave jerks or nystagmus. There was torticollis with a head tilt to the left and left shoulder elevation (Video S3). On finger–nose testing, there was ataxia bilaterally (Video S3). There was no myoclonus (Video S3). Muscle tone and power were normal in all 4 limbs (including proximal muscle groups). Reflexes were brisk globally. There was no clonus, plantar reflexes were down, and sensation was normal in all modalities. The patient held a pen tightly; however, without hyperextended, adducted wrist (since childhood; Video S3). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment test score was 26/30 (2 points lost for visuospatial skills, 1 for attention, 1 for delayed recall).

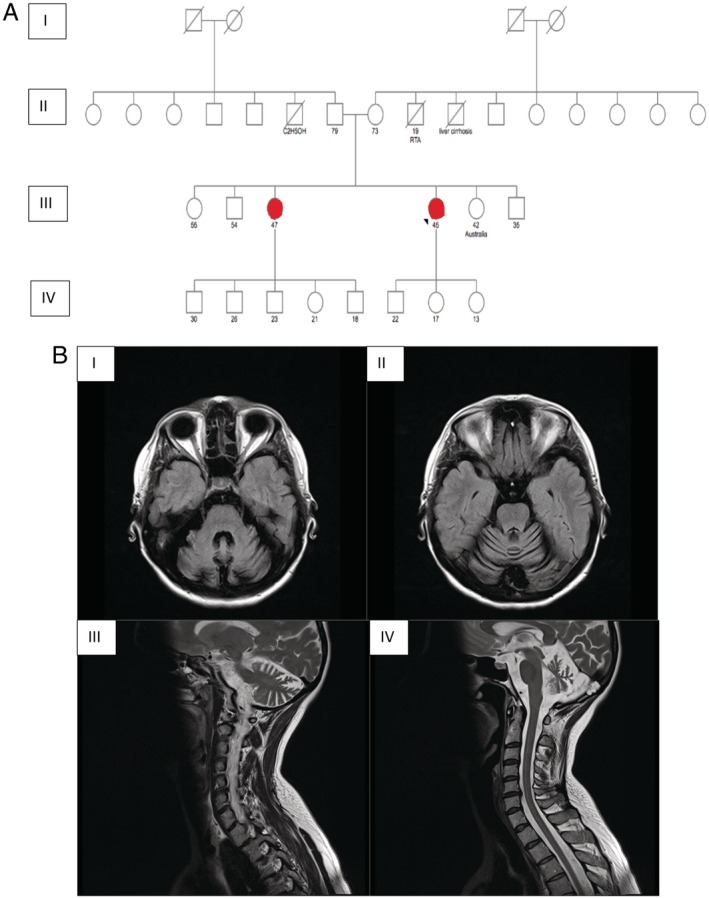

Figure 1.

(A) Family pedigree (red = affected). (B) Brain magnetic resonance imaging of the proband demonstrating cerebellar atrophy, I and II axial and III, IV sagittal T2‐weighted images.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (1.5 T) showed atrophy of the cerebellar hemispheres and vermis, but normal basal ganglia (there was no evidence of mineralization or iron deposition; Fig. 1B). Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine was normal. Investigations, including autoimmune, paraneoplastic, coeliac screen, HIV, Treponema pallidum, Lyme disease, hepatitis, vitamin E, copper studies, alpha‐fetoprotein, very long chain fatty acids analysis, and lysosomal enzyme screen, were normal. Lumbar puncture showed normal cerbrospinal fluid glucose (3.2 mmol/L, serum 4.8 mmol/L) and protein levels (0.34 g/L; range 0.15–0.45); oligoclonal bands were not present in the cerbrospinal fluid. Laryngoscopy showed normal vocal cords. Computed tomography of the thorax, abdomen, pelvis, and mammogram were normal. Echocardiogram was normal, and nerve conduction studies were unremarkable. Quadriceps muscle biopsy revealed no abnormality. Genetic analysis for spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) 1, 2, 3, and 6 and dentatorubral–pallidoluysian atrophy was negative. We tested for the common causes of autosomal recessive (AR) ataxia such as spastic paraplegia type 7 (HSP/ATX‐SPG7), and Friederich's ataxia (ATX‐FXN) that were all negative.1 Testing for pathogenic variants in the proteolipid protein 1 gene (Pelizaeus Merzbacher syndrome; HSP/ATX‐PLP1) was normal. Whole‐exome sequencing was performed by one of the commercially available providers. It encompassed testing for 6700 genes with known associated clinical phenotype sequenced on the Ilumina platform with a coverage of >98% targeted bases covered at >20×. Raw sequence data analysis, including base calling, demultiplexing, alignment to the hg19 human reference genome, and variant calling, was performed using validated in‐house genetic software of a commercially available provider.9 Relevant variants reported in human gene mutation database (HGMD),10 ClinVar,11 or in CentoMD9 as well as variants with minor allele frequency of <1% in the GnomAD12 database were considered.

Whole‐exome sequencing testing revealed 2 heterozygous variants in STUB1 gene NM_005861.3 c.358+1 G>A in intron 2 predicted to disrupt the highly conserved donor splice site of exon 2 and classed as likely pathogenic as per the American Guidelines of Genetics and Genomics13 and c.566A>C (p.Asp189Ala) in exon 4—a variant of unknown significance (class 3). Both variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. p.Asp189Ala (rs776190994) was not found in 1000G database.13 The reported allele frequency in the European non‐Finnish population as per GnomAD was 0.000008941 and in all populations was 0.000004021 (Supplementary Table S1).12 The in sillico tools were not in agreement regarding its pathogenicity (although Mutation Taster14 predicted it to be disease causing, polymorphism phenotyping v215 classed it as benign, and the scale‐invariant feature transform16 as tolerated)13 (Supplementary Table S1).

Further testing for gonadotropin and sex hormone levels showed a pattern consistent with menopause (high FSH and LH levels).

The patient received botulinum toxin injections on 2 occasions (right sternocleidomastoid muscle 30 units and left levator scapulae 30 units botulinum toxin A) with little effect and was not keen to proceed with higher doses.

Case 2

The patient's sister also had dysarthria (as per her family the voice pattern was similar to that of the proband), which developed along with memory problems at age 46. She had 5 children aged 30, 26, 23, 21, and 18 years old. All were asymptomatic. Unfortunately no further clinical information was available, and she declined medical assessment on several occasions. Four other siblings were asymptomatic (Fig. 1). The proband's father aged 79 and mother aged 73 were asymptomatic.

Discussion

Recent genetic studies suggested the molecular pathways of dystonia and ataxia being closely intertwined. With more than 100 genetic conditions associated with a phenotypic spectrum encompassing both entities,17 there has been emerging data suggesting that dystonia is a network disorder involving both the cerebellum and basal ganglia—2 closely interconnected structures rather than the disorder related solely to the abnormalities in the basal ganglia. This concept has been supported by clinical studies (cerebellar abnormalities reported in patients with cervical dystonia),18 by a number of neuroimaging studies including diffusor tensor imaging, tractography, and [18F]‐fluorodeoxyglucose–positron‐emission tomography, and animal studies.18 Cerebellar Purkinje cell dysfunction in a mouse model of combined ataxia and dystonia revealed the Purkinje cell role in both entities (dystonia developed with a Purkinje cell dysfunction and was abated with cell loss at which point worsening of ataxia was seen).18 Another study in normal mice showed that excitatory microinjections (of kainic acid) into the cerebellar cortex resulted in limb and trunk dystonia. Interestingly, it was also shown that the dysfunction of the limited part of the cerebellum results in focal dystonia, and the dysfunction of the entire organ leads to movements resembling generalized dystonia.19

When investigating a condition encompassing ataxia and dystonia it is important to consider accompanying features and family history. When family history is suggestive of an autosomal‐recessive pattern of inheritance, Friederich's ataxia (ATX‐FXN), ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ARL13B, ATX‐ATM), and AOA1 (ATX‐APTX) and 2 (ATX‐SETX) are the top differential diagnoses.1 It is prudent to remember the reversible causes of ataxia such as vitamin E deficiency (ATX‐TTPA; clues include proprioception loss, pyramidal signs, retinopathy),17 Refsum's disease (ATX‐PHY; anosmia, retinitis pigmentosa, hearing loss, ichthyosis), or biotin‐thiamine‐responsive basal ganglia disease (mutations in the SLC19A3 gene).1, 17 Dystonia may be associated with metabolic disorders such as, for example, Willson's disease (DYT/ATX‐ATP7B; Kayser‐Fleischer ring, liver disease, parkinsonism, myoclonus),17 neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA; NBIA/DYT/PARK‐CP, NBIA/DYT‐PANK2, NBIA/DYT/PARK‐PLA2G6), lysosomal storage disorders (eg, Pelizaeus Merzbacher disease [ATX/HSP‐GJC2], Niemann‐Pick type C), mitochondrial disorders, and parkinsonian disorders.1, 17

If the family history was suggestive of an autosomal‐dominant inheritance, the combination of ataxia and dystonia would prompt further analysis for the SCA spectrum disorders, including SCA1 (pyramidal signs, muscular atrophy, decreased deep tendon reflexes, loss of proprioception, bulbar dysfunction), SCA2 (pyramidal signs, peripheral neuropathy, fasciculations, muscle atrophy, parkinsonism, autonomic dysfunction), SCA3 (nystagmus, pyramidal signs, peripheral neuropathy, muscle atrophy), SCA6 (diplopia, dizziness, peripheral neuropathy), and SCA17 (chorea, cognitive impairment, parkinsonism, behavioral changes).1, 17 Dystonia may also be paroxysmal or episodic such as seen in paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (associated with mutation in the PRRT2 gene), and episodic ataxia type 2.17

Following initial negative genetic testing including trinucleotide disorders, the whole‐exome sequencing result in our patient was suggestive of autosomal‐recessive SCA16 (ATX‐STUB1).

As the condition is inherited in an autosomal‐recessive fashion, it would be ideal to test the probands’ parents to confirm the mode of inheritance; however, the family declined genetic testing. The genetic testing of the affected proband was performed as part of the clinical workup and investigation to find the cause of the symptoms. The proband was keen to have a definitive diagnosis and consented to all the testing; however, the proband's parents were elderly, and did not consent to engage with the testing as both were asymptomatic and felt it was not necessary. The affected sister was estranged and did not consent to engaging with any medical professional as she reportedly did not acknowledge her symptoms. This was discussed several times with the proband and her son. To overcome this limitation, we proceeded to TOPO cloning to determine the position of the variants (in cis or in trans). The analysis confirmed compound heterozygosity (variants were in trans) consistent with autosomal‐recessive mode of inheritance. The combination of 1 variant predicted to be pathogenic and another variant of an unknown significance in STUB1 gene posed a diagnostic dilemma. As per the American Guidelines of Genetics and Genomics guidelines,13 the c.566A>C (p.Asp189Ala) variant in exon 4 of the STUB1 gene fulfils 2 moderate criteria supporting its pathogenicity: (1) PM3, cis/trans testing (in cases where there are 2 heterozygous variants identified in a gene implicated in a recessive disorder and the variant in question is in trans with the variant known to be pathogenic this can be considered a moderate evidence); and (2) PM2, absent from controls (or at extremely low frequency if recessive) in known databases (c566A>C, minor allele frequency 0.000004021). The in sillico tools were not in agreement regarding this variant pathogenicity, and the conservation was predicted as moderate among species. Further analysis of this variant (Human Splicing Finder)20 predicted an alteration of an exonic splicing enhancer site and the potential alteration of splicing (some point mutations can have severe effects on the structure of the encoded protein when they inactivate an exonic splicing enhancer resulting in exon skipping).21 c.358+1 G>A in intron 2 was predicted to cause alteration of the WT donor site, most probably affecting splicing.

Pathogenic variants in STUB1 were first described in 20132, 3 and are associated with a phenotypic spectrum including SCA, cognitive decline, and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Dystonia is not frequently reported. Associated disease phenotypes are autosomal SCAR16 (ATX‐STUB1),2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 autosomal‐dominant SCA48,19 and Gordon Holmes syndrome (ATX‐RNF216).22 Gordon Holmes syndrome (MIM 212840; ATX‐RNF216)22 combines autosomal‐recessive ataxia with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (low FSH and LH levels). High FSH and LH levels in our patient, consistent with menopause, normal puberty, and fertility, ruled out the possibility of Gordon Holmes syndrome. SCA4823 is a newly described entity in 3 family members with ataxia and cognitive affective syndrome caused by a heterozygous mutation in STUB1 gene. As 1 of the 2 heterozygous variants in our patient was classified as a variant of unknown significance, a diagnosis of SCA48 could be considered; however, this would be unlikely as there was no autosomal‐dominant family history of ataxia.

The phenotype combined with a genetic analysis in our patient are most consistent with the diagnosis of SCAR16 (ATX‐STUB1). This entity was first described in 2014 by Shi and colleagues in 4 siblings from China, all of whom had dysarthria.2, 3 To date, there have been 15 families (with 29 members) reported with SCAR16 (ATX‐STUB1; detailed phenotypic data including our patient are presented in Table 1).2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 24, 25, 26 A total of 20 pathogenic variants in the STUB1 gene causing SCAR16 (ATX‐STUB1) have been described, including truncation, missense, and splice site donor mutation.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Dystonia in SCAR16 (ATX‐STUB1) has been described in 1 report of 2 brothers (of 3 affected family members by SCAR16) by Kawarai and colleagues.8 The age at onset of ataxia was much younger than in our patient: 1 patient was aged 19 (aged 45 at dystonia onset), and the second was aged 24 (aged 37 at dystonia onset) in comparison with the age at onset of 45 (for both ataxia and dystonia) in our patient.8 Although Kawarai and colleagues report dystonic posturing of the head and trunk in the proband and dystonia of the left foot in the proband's brother,8 our patient was affected by both neck and foot dystonia, without truncal dystonia. Both individuals had myoclonus and cognitive impairment unlike our patient.8 Our patient is one of the oldest to develop SCAR16 (ATX‐STUB1) described in the literature where age at onset ranged from a few months to age 57 (there were 3 patients older than our patient [aged 49, 54, and 574, 22, 23], whereas all others were younger than age 332, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 24, 25, 26). All described patients had ataxia with 86.2% having dysarthria and 62% having cognitive impairment (Table 1).2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 24, 25, 26 Dystonia was reported in 3/29 (10.3%) patients with SCAR16 in the literature (including our patient).2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 24, 25, 26 The prevalence of dystonia is equal to the prevalence of chorea/choreoathetosis and ophthalmoplegia in this condition.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 24, 25, 26 The genetic testing for mutations in STUB1 gene should be therefore kept in mind while assessing patients with ataxia and dystonia and the reason is twofold. First, the autosomal‐recessive pattern of inheritance may result in the affected individuals not being easily identified (if the family history taking is limited for example because of time constraints or being estranged from the extended family). Second, commercial providers do not include STUB1 testing either in the dystonia panel or in the ataxia panel (the most frequent tests ordered initially). STUB1 is included solely in the comprehensive ataxia panel (by some providers), and the clinician has to keep STUB1 mutations as a cause of ataxic–dystonic syndromes in the back of their minds to ensure they proceed to the most appropriate testing (be it the comprehensive ataxia panel or whole‐exome sequencing).

Table 1.

Phenotypic summary of all described individuals with autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16 to date

| Shi et al. 2013 | Shi et al. 2014 | Synofzik et al. 2014 | Heimdal et al. 2014 | Depondt et al. 2014 | Cordoba et al. 2014 | Bettencourt et al. 2015 | Kawari et al. 2016 | Gazulla et al. 2018 | Turkgenc et al. 2018 | Olszewska et al. 2019 | All/Summary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country/region | China | China | Germany, Turkey, Saudi Arabia | Middle East | Belgium | Argentina | Spain | Japan | Spain | Northern Cyprus | Ireland | Asia, Europe, South America |

| Families number, sibling number |

3 family 1:4 family 2:1 family 3:1 |

1 2 |

3 family 1:1 family 2:1 family 3:2 |

1 4 |

1 2 |

1 1 |

1 2 |

1 3 |

1 1 |

1 3 |

1 Data on 1 |

15 29 |

| Age at onset | 14–20 | 17, 19 | 2–49 | 0–2, 33 | 23, 25 | 15 | 20s, 22 | 15–24 | 54 | 31–57 | 45 | 0–57 |

| Ataxia | 6/6 | 2/2 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 100% (29/29) |

| Dysarthria | 6/6 | 2/2 | 0 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 86.2% (25/29) |

| Cognitive impairment | 2/6 | 2/2 | 1/4 | 3/4 | 2/2 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 1/3 | 0 | 62% (18/29) |

|

Brisk reflexes |

4/6 |

1/2 |

2/4 |

0 | 2/2 | 1/1 |

2/2 |

1/3 | 0 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 58.6% (17/29) |

|

Pyramidal signs |

4/6 |

4/4 |

||||||||||

| Nystagmus | 2/6 | 1/2 | 0 |

2/3 1 unknown |

0 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/1 | 1/3 | 0 | 35.7% (10/28) |

| Myoclonus | 0 | 0 | 1/4 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 3/3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24.1% (7/29) |

| Head/hand tremor | 0 | 1/2 | 0 | 1/4 | 0 | 1/1 | 0 | 2/3 | 0 | 3/3 | 0 | 27.5% (8/29) |

| Decreased position sense | 4/6 | 0 | 1/4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17.2% (5/29) |

| Hypogonadotropic hypogondism | 0 | 2/2 | 0 |

1/3 1 unknown |

0 | 0 | 0 | Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12% (3/25) |

| Dystonia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/3 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 | 10.3% (3/29) |

| Chorea/choreoathetosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/1 | 0 | 0 | 10.3% (3/29) |

| Opthalmoplegia | 2/6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.3% (3/29) |

Conclusion

In this report, we expand the genotype and phenotype associated with SCAR16 (ATX‐STUB1). We provide evidence for a novel, previously not reported, and potentially implicated variant and report the second family with dystonia as a prominent phenotypic feature.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

D.A.O.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3A

J.A.K.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement

The authors confirm that the approval of an institutional review board was not required for this work. The authors confirm that the written informed patient's consent was obtained for this work. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No specific funding was received for this work. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

Financial Disclosures for Previous 12 Months

The authors declare that there are no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Supplementary Figure S1. Conservation across species for A c.566A>C (p.Asp189Ala) in exon 4 and B c.358+1 G>A in intron 2 in the stress‐inducible phosphoprotein‐1 (STIP1) homology and U‐box containing protein 1 (STUB1) gene detected in the proband (source Mutation Taster).

Supplementary Table S1. In sillico prediction scores, minor allele frequency, and conservation scores presented for c.358+1 G>A in intron 2 and c.566A>C (p.Asp189Ala) in exon 4 in the STIP1 homology and U‐box containing protein 1 (STUB1) gene detected in the proband. phastCons and phyloP determine the grade of conservation of a given nucleotide. phastCons values: 0 to 1: probability that each nucleotide belongs to a conserved element (the closer to 1 the more probable it is conserved) based on the multiple alignment of genome sequences of 46 different species. phyloP (values between −14 and + 6) measures conservation (slower evolution than expected under neutral drift) and acceleration (faster than expected). Conserved sites, positive scores; fast evolving, negative scores. CADD; combined annotation dependent depletion; GERP, genomic evolutionary rate profiling; GnomAD, the Genome Aggregation Database; MAF, minor allele frequency; PhastCons, conservation scoring and identification of conserved elements; PhyloP, computation of P values for conservation or acceleration; PolyPhen2, polymorphism phenotyping v2; SIFT, the scale‐invariant feature transform.

Video S1. Proband's gait: dragging and inward turning of the right foot, unsteady gait requiring walking aid.

Video S2. Examination of the proband: dysarthria, cervical dystonia (anterocollis, left torticollis and left shoulder elevation), sensory trick (touching the back of the head).

Video S3. Proband's examination demonstrates cervical dystonia, no evidence of postural tremor, myoclonus, or dystonic posturing of the hands; there is finger–nose ataxia present and slight bilateral intention tremor; there is no dysdiadochokinesis; and the patient is holding a pen tightly while writing.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Beaudin M, Klein CJ, Rouleau GA, Dupre N. Systematic review of autosomal recessive ataxias and proposal for a classification. Cerebellum Ataxias 2017;4:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shi Y, Wang J, Li JD, et al. Identification of CHIP as a novel causative gene for autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia. PLoS One 2013;8:e81884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shi CH, Schisler JC, Rubel CE, et al. Ataxia and hypogonadism caused by the loss of ubiquitin ligase activity of the U box protein CHIP. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:1013–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Synofzik M, Schule R, Schulze M, et al. Phenotype and frequency of STUB1 mutations: next‐generation screenings in Caucasian ataxia and spastic paraplegia cohorts. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heimdal K, Sanchez‐Guixe M, Aukrust I, et al. STUB1 mutations in autosomal recessive ataxias—evidence for mutation‐specific clinical heterogeneity. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Depondt C, Donatello S, Simonis N, et al. Autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia of adult onset due to STUB1 mutations. Neurology 2014;82:1749–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cordoba M, Rodrigues‐Quiroga S, Gatto EM, Alurralde A, Kauffman MA. Ataxia plus myoclonus in a 23‐year‐old patient due to STUB1 mutations. Neurology 2014;83:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kawarai T, Miyamoto R, Shimatani Y, Orlacchio A, Kaji R. Choreoathetosis, dystonia, and myoclonus in 3 siblings with autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16. JAMA Neurol 2016;73(7):888–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Henrie A, Hemphill SE, Ruiz‐Schultz N, et al. ClinVar miner: demonstrating utility of a web‐based tool for viewing and filtering ClinVar data. Hum Mut 2018;39(8):1051–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stenson PD, Ball EV, Mort M, Phillips AD, Shiel JA, Thomas NS. The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®): 2003 update. Hum Mutat 2003;21:577–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centogene: The Rare Disease Company. https://www.centogene.com/pharma/mutation-database-centomd.html. Last accessed on 15 February 2020.

- 12. Karczewski Kj, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. Variation across 141,456 human exomes and genomes reveals the spectrum of loss‐of‐function intolerance across human protein‐coding genes. bioRxiv 531210. 10.1101/531210 [DOI]

- 13. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015;17(5):405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schwarz JM, Rödelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease‐causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Method 2010;7(8):575–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. PolyPhen2. Nat Method 2010;7(4):248–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vaser R, Adusumalli S, Leng SN, Sikic M, Ng PC. SIFT missense predictions for genomes. Nat Protocol 2016;11:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rossi M, Balint B, Millar Vernetti P, Bhatia KP, Merello M. Genetic dystonia‐ataxia syndromes: clinical spectrum, diagnostic approach, and treatment options. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2018;5(4):373–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nibbeling EAR, Delnooz CCS, de Koning TJ, et al. Using the shared genetics of dystonia and ataxia to unravel their pathogenesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017;75:22–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bologna M, Berardelli A. Cerebellum: an explanation for dystonia? Cerebellum Ataxia 2017;4:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod‐Beroud G, Claustres M, Beroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37(9):e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cartegni L, Wang J, Zhu Z, Zhang MQ, Krainer AR. ESEfinder: a web resource to identify exonic splicing enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res 2003;31(13):3568–3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendelian Inheritance in Man (MIM) #212840. Gordon‐Holmes syndrome. https://www.omim.org/entry/212840

- 23. Genis D, Ortega‐Cubero S, San Nicolás H, Corral J, Gardenyes J. Heterozygous STUB1 mutation causes familial ataxia with cognitive affective syndrome (SCA48). Neurology 2018;91(21):e1988–e1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bettencourt C, de Yebenes JG, Lopez‐Sendon JL, et al. Clinical and neuropathological features of spastic ataxia in a Spanish family with novel compound heterozygous mutations in STUB1. Cerebellum 2015;14(3):378–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gazulla J, Izquierdo‐Alvarez S, Sierra‐Martinez E, Marta‐Moreno ME, Alvarez S. Inaugural cognitive decline, late disease onset and novel STUB1 variants in SCAR16. Neurol Sci 2018;39(12):2231–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Turkgenc B, Sanlidag B, Eker A, et al. STUB1 polyadenylation signal variant AACAAA does not affect polyadenylation but decreases STUB1 translation causing SCAR16. Hum Mutat 2018;39(10):1344–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1. Conservation across species for A c.566A>C (p.Asp189Ala) in exon 4 and B c.358+1 G>A in intron 2 in the stress‐inducible phosphoprotein‐1 (STIP1) homology and U‐box containing protein 1 (STUB1) gene detected in the proband (source Mutation Taster).

Supplementary Table S1. In sillico prediction scores, minor allele frequency, and conservation scores presented for c.358+1 G>A in intron 2 and c.566A>C (p.Asp189Ala) in exon 4 in the STIP1 homology and U‐box containing protein 1 (STUB1) gene detected in the proband. phastCons and phyloP determine the grade of conservation of a given nucleotide. phastCons values: 0 to 1: probability that each nucleotide belongs to a conserved element (the closer to 1 the more probable it is conserved) based on the multiple alignment of genome sequences of 46 different species. phyloP (values between −14 and + 6) measures conservation (slower evolution than expected under neutral drift) and acceleration (faster than expected). Conserved sites, positive scores; fast evolving, negative scores. CADD; combined annotation dependent depletion; GERP, genomic evolutionary rate profiling; GnomAD, the Genome Aggregation Database; MAF, minor allele frequency; PhastCons, conservation scoring and identification of conserved elements; PhyloP, computation of P values for conservation or acceleration; PolyPhen2, polymorphism phenotyping v2; SIFT, the scale‐invariant feature transform.

Video S1. Proband's gait: dragging and inward turning of the right foot, unsteady gait requiring walking aid.

Video S2. Examination of the proband: dysarthria, cervical dystonia (anterocollis, left torticollis and left shoulder elevation), sensory trick (touching the back of the head).

Video S3. Proband's examination demonstrates cervical dystonia, no evidence of postural tremor, myoclonus, or dystonic posturing of the hands; there is finger–nose ataxia present and slight bilateral intention tremor; there is no dysdiadochokinesis; and the patient is holding a pen tightly while writing.