Implications.

Cattle temperament can be described based on reactivity to human handling, novel objects, or stressful situations. Despite its economic and welfare implications, there is a lack of objective indicator traits and limited incorporation of temperament in dairy cattle breeding programs.

The increased intensification of dairy production systems, including the adoption of robotic milking machines and automatic feeders, is contributing to a growing interest to selectively breed for improved temperament and milking efficiency.

The main challenges for wider incorporation of temperament in dairy breeding programs are the definition of indicator traits, large-scale phenotyping, lack of understanding of the genetic background of the traits, and availability of the economic values of temperament.

Genomics combined with high-throughput phenotyping will be essential to optimize selection for improved temperament traits in dairy cattle.

Introduction

Since domestication, cattle populations have been intensively selected for various behavioral traits based on phenotypic characteristics, especially those related to handling ease. The industrial revolution and the rapid expansion of the world population (i.e., greater food demand) over the past decades contributed to the development of intensive dairy cattle production systems and a greater use of technology on farms. In most countries, pasture-based and smallholder farms are being replaced by large-scale production systems with animals raised in indoor facilities. Consequently, animals are required to adapt and perform in such systems with minimal training and human–animal interaction. In this context, dairy cows can have reduced welfare and productivity due to fear of strange objects and machines and uncommon activities.

There is a growing interest in genetic selection to improve behavioral traits, especially those linked to ease of management and well-being in intensive production systems. The main objectives of this review are: 1) to present the progress achieved toward the implementation of temperament traits in dairy cattle breeding programs around the world and 2) to discuss the challenges and opportunities of incorporating temperament traits in dairy cattle selection indexes (using Chinese dairy cattle as an example), including the definition of appropriate phenotypes, genotype-by-environment interactions (G × E), calculations of economic values, and genomic selection.

Indicators of Dairy Cattle Temperament

Temperament can be defined based on the animal’s reactivity to human handling and response to novel objects or stressful situations. The assessment of cattle temperament can provide important information on the physical, physiological, and psychological state of the animal, including immunity, stress level, and metabolic processes. For instance, milking temperament has been associated with udder health (Santos et al., 2018), survival (Cue et al., 1996), rectal temperature and milk yield (Chang et al., 2019), reproductive performance (Sewalem et al., 2011), milking speed (Kramer et al., 2013), performance in automated milking system (AMS, Wethal and Heringstad, 2019), and conformation traits (Cue et al., 1996; Sewalem et al., 2011).

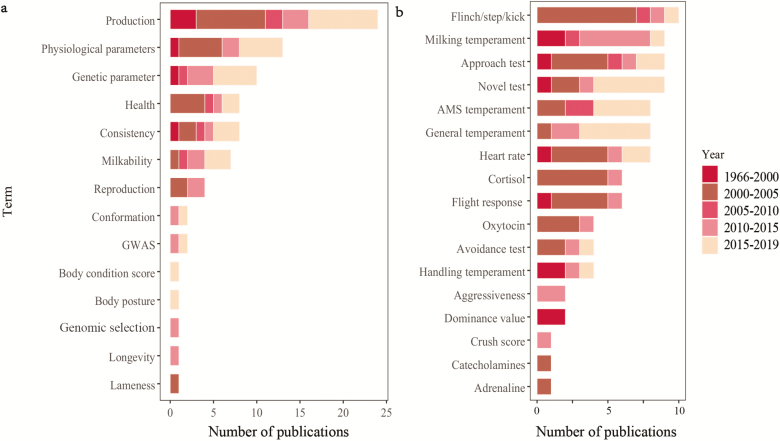

Understanding the genetic relationship between temperament and other important traits in dairy cattle has been a research focus for a very long time. Based on a detailed literature search, “production,” “physiological parameters,” and “genetic parameters” were the main terms associated with research in the area of dairy cattle temperament (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of (a) topics and (b) indicator variables associated with dairy cattle temperament, based on scientific reports published between 1966 and 2019. Consistency: repeatability across time and events in temperament traits. GWAS, genome-wide association study; AMS, automatic milking system.

In general, inclusion of a novel trait in a breeding program (e.g., temperament) requires several steps: 1) the breeding goal needs to be defined, which can be done by any component of the dairy industry (e.g., farmer, retailer, and consumer); 2) an indicator trait needs to be chosen (e.g., milking temperament score on a scale from 1 to 5) based on the practically and economic feasibility of phenotypic recording; 3) the heritability and genetic correlations with traits already under selection need to be accurately estimated; and 4) the economic value of the trait and selection index weighting needs to be determined. This process is not static and depends on the availability of novel technologies to better measure indicator traits, advanced statistical and bioinformatic tools and methods, and refinement of breeding goals by the industry.

Behavioral tests

Behavioral reactions that are indicators of temperament can be measured during stressful handling procedures and human–animal interactions. In general, fear of humans, curiosity to novelty, and adaptability to handling are the main variables considered in behavioral tests. For instance, flight distance can be assessed by measuring the distance that a human can approach a stationary cow before she moves away. This distance can also be converted to speed by measuring distance and time, that is, flight speed. A large flight distance or high flight speed indicates a poorer temperament or “fearful” animal. Furthermore, the closest distance that a cow voluntarily approaches a stationary human has been described as approach distance. This indicates the animal’s confidence in the human as well as the animal’s exploratory ability. Tilbrook et al. (1989) also measured the time and number of interactions with humans in an approach test. In addition to a novel human test, novel areas, or object tests have been used to evaluate the animal’s neophobia (Foris et al., 2018). The novel area test is often termed as “open-field test” in which the cow is free to move within a defined area, also considering the frequency and intensity of vocalizing, movements, urinating, defecating, and escape events (Gibbons et al., 2011; Foris et al., 2018). These temperament tests are more suitable for small-scale applications (e.g., research or small farms). However, they are labor intensive in large dairy cattle operations. Usually, temperament metrics based on restraining the cows during weighing, feeding or milking, crush score (Gibbons et al., 2011), milking temperament score or flinching, stepping, and/or kicking score are often recorded on a subjective matter (e.g., scales from 1 to 3, 1 to 4, 1 to 5, 1 to 9, or 1 to 50; Sewalem et al., 2010; Sutherland and Dowling, 2014; Stephansen et al., 2018). For instance, Chang et al. (2019) evaluated the response of Chinese Holstein cattle on a 3-point scale (1: calm, 2: intermediate, and 3: temperamental) when measuring cows’ rectal temperature in a restraint test. These tests are reasonably safe, quick, and simple to implement on-farm, but subjective (i.e., dependent on the training of farmers or technicians).

Milking temperament based on AMS

AMS or milking robots are becoming popular around the world. There are over 38,000 AMS operating in worldwide dairy farms (Sandgren and Emanuelson, 2017), with the greatest proportion located in Northern Europe (Barkema et al., 2015) and North America. There are countries (e.g., the Netherlands and Norway) with 30–45% of cows milked through AMS and this is predicted to increase up to 50% in the next few years (Tine, 2017). In the United States and Canada, there are over 3,000 AMS stations. A significantly growing number of AMS in Canada was reported (Barkema et al., 2015), and more than 11% of milk recorded herds used AMS in 2018. In China, the adoption of AMS is low due to the large average herd size (~851 cows; DAC, 2019) and relatively low labor costs.

With the increasing use of AMS, the accuracy of traditional milking temperament scoring might decrease due to a reduced interaction between animals and farmers (Stephansen et al., 2018) and therefore, better indicators of temperament are needed. Unsuccessful milking and poor milkability influence the capacity and efficiency of AMS and consequently, the farmers’ profitability. The number of rejected and incomplete milking, kickoffs, and teats not found are promising indicators of temperament in AMS (Wethal and Heringstad, 2019). There are several advantages of assessing temperament based on AMS information: 1) it does not interfere with the farm routine activities and no additional labor is required; 2) it generates standardized (and objective) measures across individuals and large amount of repeated records per animal, which are crucial for more accurate genetic analysis; and 3) it has greater phenotypic variability when compared with subjective scoring systems. Therefore, variables collected in AMS are promising indicator traits to improve milking temperament.

Additional Data Sources

The use of novel technologies and data sources is essential to standardize temperament assessment across farms, and thus improve genetic progress for dairy cattle temperament. This includes technological devices such as video-imagining, activity-collars (Figure 2a), pedometers (Figure 2b), and metabolite profiling.

Figure 2.

Technological devices such as (a) activity-collars and (b) pedometers.

Activity monitors

Activity monitors (e.g., pedometers, collars, and microchip sensors) can be used to detected many behavioral and physiological activities (e.g., reproduction and feeding behavior). For instance, activity-collars infer animals’ movement through an accelerometer usually placed on the animal’s neck. Another example of activity sensor is a molded microchip coupled to an identification ear tag, which assesses ear temperature, rumination activity, eating behavior, and cow activity. Another example is a sensor node installed on the animal’s neck to capture body temperature, respiration rate, and movement. Temperament can be assessed through regression of animal locomotion (e.g., active or resting), blood pressure, temperature, respiration rate, and other variables already accessed from activity monitors. In this context, developing algorithms to predict temperament based on high-throughput phenotypes (e.g., pedometers, activity-collars, and microchip sensors) are an emerging area of research.

Video-imagining

The cost-effectiveness and accessibility of video technology and computer image processing methods have created opportunities to better measure dairy cattle temperament. Video-imaging analysis has been used for several purposes in cattle, including lameness detection and carcass traits. This is an emerging research area that is expected to grow substantially over the next few years, especially in line with the development of machine learning methods.

Physiological biomarkers

Biomarkers are also another group of variables that can be used to indicate cattle temperament. For instance, biomarkers linked to stress level (e.g., heart rate, eye temperature, and cortisol levels) have been correlated with temperament traits (e.g., chute test, separation, and restraint test) in German Simmental and Charolais cattle (Geburt et al., 2015). More reactive dairy animals have been shown to have increased plasma and salivary cortisol concentrations and higher cardiac autonomic responsiveness to transrectal examination than less reactive cows (Kovács et al., 2016). Metabolite profiling (e.g., serum) is also another important method to identify novel indicators of temperament. For instance, physiological parameters of cows with divergent temperament have been shown to differ, including hormones, neurotransmitters, neuromodulators (Réale et al., 2007), and concentration of prefrontal cortex and serum metabolites (Brand et al., 2015). Furthermore, temperamental dairy cows have been reported to have elevated cortisol concentrations and endogenous opioids in plasma, reduced oxytocin concentrations, and increased heart rate in unfamiliar milking surroundings. Furthermore, Chang et al. (2019) reported a moderate genetic correlation between temperament score and rectal temperature.

Statistical Approaches to Analyze Temperament Traits

Temperament traits are usually measured in categorical levels (discrete or noncontinuous variables). Some alternatives to analyze these traits are: 1) to assume that the categories follow a continuous distribution when phenotypic records are well distributed across four or more categories and then use the traditional mixed model equations (MME); 2) to convert categorical numbers to scaled values (e.g., probabilities), which can then be considered as a continuous trait and analyzed through the traditional MME; 3) to use a Bayesian threshold model, which is the most recommended alternative for analyzing categorical traits; and 4) to fit a multiple trait model and each phenotypic category is considered as a different trait. In addition, continuous phenotypes (e.g., flight speed) can be analyzed using the traditional MME. High-throughput phenotypes from precision technologies (e.g., milking robots) and video-imaging can be analyzed using more sophisticated machine learning approaches such as deep learning and neural networks.

Genetic Background of Temperament Traits

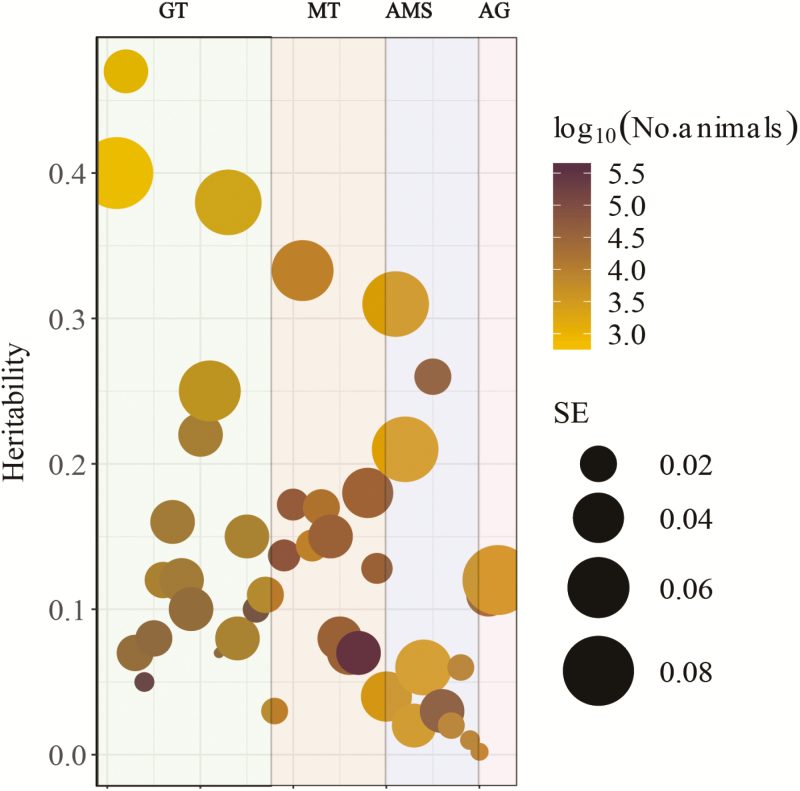

In general, dairy cattle temperament is a moderately heritable trait with a wide variation in heritability estimates depending on the indicator trait (0.002–0.47). Figure 3 presents 42 heritability estimates published between 1960 and 2019. Continuous phenotypes usually have higher heritability compared with subjective scores (Stephansen et al., 2018). In addition, phenotypes categorized in a smaller number of levels, such as 1–3, also have lower heritability than 1–5 or 1–9 subjective assessments. The method used for the analyses can also yield different estimates. For instance, general temperament scores (scale from 1 to 3, assessed during rectal temperature measurements) in 6,586 Chinese Holstein had a heritability of 0.024 based on a linear model using AI-REML, 0.033 when fitting a Generalized Linear Mixed Model, and 0.046 when using a threshold model in a Bayesian approach (unpublished data).

Figure 3.

Overview of heritability estimates for temperament traits in dairy cattle. Different colors indicate the temperament trait groups: GT, general temperament (general temperament is defined as the overall assessment of the individual cows’ temperament); MT, milking temperament; AMS, temperament in automatic milking systems; and AG, aggressiveness. Darker circle colors represent larger sample sizes, while the size of the circles indicate the standard error of the estimates (Supplementary Material S1).

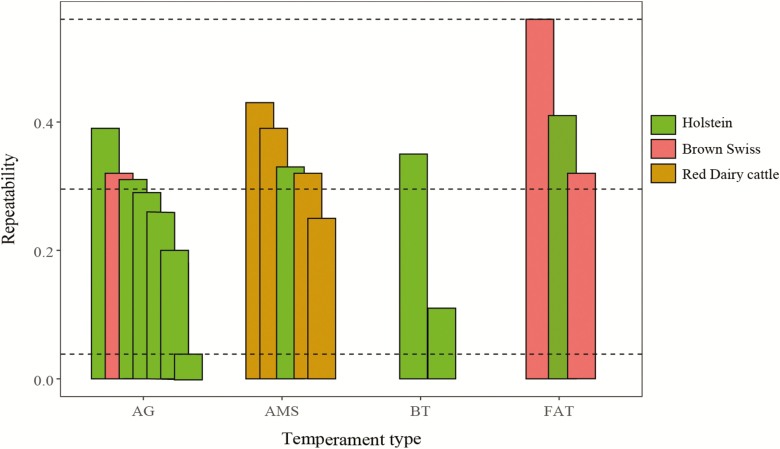

The most important characteristics of temperament phenotypes are situational and temporal repeatability. Consistency or repeatability indicates that variation among and within individuals is largely maintained across repeated measurements, which can be evaluated based on repeatability estimates (Figure 4) and intraclass correlation coefficients. With the exception from AMS-derived-traits, the interval between phenotypic recording varies from 1 mo to 1 yr. The repeatability estimates of temperament are mostly moderate, but with a wide range (0.04–0.56). Compared with other temperament trait groups, the repeatability of three farmer-assessed temperament traits were relatively high (0.32–0.56; Erf et al., 1992; Kramer et al., 2013). Wethal and Heringstad (2019) revealed that the repeatability of milking temperament (incomplete milking, teats not found, rejected milkings, and kickoffs) in AMS range from 0.25 to 0.43 in Holstein, which indicates the value of repeated measures for genetic evaluation of temperament traits.

Figure 4.

Repeatability estimates for temperament traits in six dairy cattle studies. AG, aggressiveness; AMS, temperament in automatic milking systems; BT, temperament in behavioral tests; and FAT, farmer-assessed temperament (Supplementary Material S2).

Some factors influencing or linked with repeatability estimates are: breed, age, environment, habituation, learning ability, and evaluator. Cattle temperament measurements at 6–8 mo of age have been reported to be quite stable over time (Lansade et al., 2008). However, animals may become less responsive or more sensitive to the stimulation if measured repeatedly. Therefore, habituation should be avoided in novel tests.

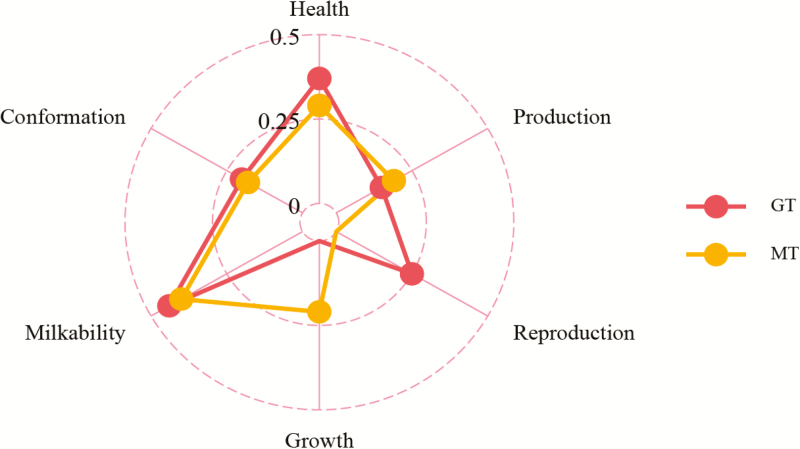

Understanding the genetic association between temperament and other important traits is paramount for sustainable long-term selection. The average absolute values of genetic correlation between temperament and six other traits (i.e., health, production, reproduction, growth, milkability, and conformation) were calculated based on 15 dairy cattle studies published between 1960 and 2019 (Figure 5). In summary, temperament was observed to be favorably correlated with longevity (Sewalem et al., 2010). The genetic correlation between calving-to-first service and temperament was close to zero (Chang et al., 2019), whereas a strong favorable genetic correlation between calving ease (0.48 ± 0.18) and number of services (0.56 ± 0.50) with temperament score was observed (Chang et al., 2019).

Figure 5.

Average absolute values of genetic correlation estimates between temperament traits and health, production, reproduction, growth, milkability, and conformation traits in dairy cattle. GT, general temperament; MT, milking temperament (Supplementary Material S3).

Regarding production traits, it is plausible that calm cows take less time to be milked, which agrees with the genetic correlations between milk speed and general or milking temperament ranging from 0.23 (Cue et al., 1996) to 0.57 (Visscher and Goddard, 1995). A moderate and favorable genetic correlation (−0.4) between fat-corrected milk yield and temperament was observed (Erf et al., 1992). However, a weak positive relationship between temperament score and milk yield has also been reported (Erf et al., 1992; Chang et al., 2019). There could be a competitive relationship for allocation of resources between production and temperament traits. Hence, more studies are needed to better understand the genetic relationships and underlying biological mechanisms of temperament and other relevant traits.

The majority of molecular genetic studies of behavioral traits have been focused on mice, drosophila, and humans. There are relatively few studies detecting candidate genes and Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) in dairy cattle. This includes 135 QTLs for 15 cattle behavior traits (AnimalQTLdb, 2019), including 14 QTLs (Table 1) identified in Holstein (Hiendleder, 2003; Kolbehdari et al., 2008) and 71 QTLs in Holstein and Charolais crossbred animals (Gutierrez-Gil et al., 2008; Friedrich et al., 2016). The largest number of QTLs significantly associated with temperament was observed on BTA29 and overlapping QTLs were found on BTA10 and BTA29 for different behavioral tests (Gutierrez-Gil et al., 2008; Friedrich et al., 2016). Genome-wide association studies and functional validation of candidate genes using large genomic and phenotypic datasets are still needed.

Table 1.

Genomic regions associated with temperament traits in Holstein cattle

| Chromosome | Position | Candidate gene | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BTA4 | 40,499,442 bp | NRCAM | Kolbehdari et al. (2008) |

| BTA5 | 136 cM | Hiendleder (2003) | |

| BTA13 | 60,045,226 bp | CSTF1 | Kolbehdari et al. (2008) |

| BTA18 | 105 cM | Hiendleder (2003) | |

| BTA19 | 37,837,691 bp | CACNA1G | Kolbehdari et al. (2008) |

| BTA22 | 46,425,659 bp | CACNA1D | Kolbehdari et al. (2008) |

| BTA23 | 13,897,540 bp | BYSL | Kolbehdari et al. (2008) |

| BTA26 | 34,495,734 bp | SLC18A2 | Kolbehdari et al. (2008) |

| BTA29 | 20 cM | Hiendleder (2003) | |

| BTA29 | 23,068,761 bp | LOC782544 | Kolbehdari et al. (2008) |

| BTA29 | 30,954,390 bp | NTM | Kolbehdari et al. (2008) |

| BTA29 | 36,737,805 bp | CCDC88B | Kolbehdari et al. (2008) |

| BTA29 | 38,944,167 bp | DPP3 | Kolbehdari et al. (2008) |

| BTAX | 9 cM | Hiendleder (2003) |

Incorporation of Temperament Traits in Breeding Programs

Over the past decades, milk production and conformation have been the main breeding goals in Chinese dairy cattle. Milk yield, fat yield, protein yield, type, foot and leg, mammary system, and somatic cell score are the traits currently included in the China performance index (CPI). However, temperament is still not part of the national genetic evaluation system in China. In Australia and Nordic countries, milking temperament is already integrated into selection indexes (Table 2). The relative economic weight for temperament in the Australian Profit Ranking (APR) of 8.72% is the largest weight across countries (Byrne et al., 2016). The weight for temperament in the Nordic Total Merit (NTM) is 1.33%, 1.08%, and 1.06% for Holstein, Jersey, and Red Dairy Cattle, respectively. In most countries, temperament is generally not included in the selection indexes. For instance, in Canada stand-alone estimated breeding values (EBVs) for milking temperament are reported.

Table 2.

Description of the national genetic evaluation for dairy cattle temperament in different countries

| Countries | Indicator trait | Breed(s) | Start time | Economic weight in total merit index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Scored on a 1–5 scale: the middle value is optimal | HOL, JER, GUE, RDC | 1985 | 3.51 (8.72%) |

| Canada | Scored on a 1–5 scale: nervous to calm | HOL, AYR, GUE, JER, BS, CAN, MS | – | 0 |

| Denmark, Sweden, and Finland | Scored on a 1–9 scale | HOL, JER, RDC | 1988 | HOL: 0.04 (1.33%) RDC: 0.03 (1.08%) JER: 0.03 (1.06%) |

| France | Scored on a 1–5 scale | HOL, MON, NOR, BS | 1996 | 0 |

| United Kingdom | Ease of milking | HOL | 1993 | 0 |

| New Zealand | Scored on a 1–5 scale: vicious to placid | HOL, JER, RDC | 1987 | 0 |

| Norway | Scored on a 1–3 scale: easy to uneasy | NR | 1987 | 0.42% |

| The Netherlands | Scored on a 1–9 scale | – | 1994 | 0 |

HOL, Holstein; JER, Jersey; GUE, Guernsey; RDC, Red Dairy cattle; AYR, Ayrshire; BS, Brown Swiss; CAN, Canadienne; MS, Milking Shorthorn; MON, Montbéliarde; NOR= Normande; and NR, Norwegian Red.

There are various reasons limiting the incorporation of temperament into selection indexes in dairy cattle, including difficulties to collect large-scale and standardized phenotypes and precise estimation of economic value for the trait. A more objective indicator of temperament is still required. In national genetic evaluations, subjective scoring milking temperament is still the most common indicator of temperament. In this context, Réale et al. (2007) categorized temperament traits into the following groups: shyness–boldness, exploration, avoidance, activity, sociability, and aggressiveness. Moreover, the correlation between different indicator traits has been reported to be low and some of them are even negative (Sutherland and Dowling, 2014). For instance, Purcell et al. (1988) reported a low genetic correlation (0.12) between milking temperament and flight distance and Kramer et al. (2013) reported a Pearson correlation between milking temperament and aggressiveness’s EBVs equal to 0.28. Consequently, a composite index that encompasses several temperament traits may be more appropriate than a single-trait. Analogous to overall type, one can put different weight on traits such as milking temperament, human–animal interaction, aggressiveness, and neophobia, according to their importance to specific production systems. In addition to developing selection indexes based on economic values of temperament, one could use the approach of desired gains.

As previously mentioned, technological equipment will help in the definition of more precise temperament phenotypes. It is also worth highlighting that there should be no collinearity between selected traits. However, the use of different temperament sources might not be feasible in Chinese dairy farms at the moment due to the large average herd sizes and low labor costs. The three most common types of milking parlors in China are herringbone parlors, parallel parlors, and rotary parlors, instead of AMS, so milkers are usually very familiar with cows. Type appraisers can also be in charge of the assessment of temperament.

Another challenge for including temperament in dairy breeding programs is the variety of environmental factors across production systems. Therefore, genotype-by-environment (G × E) interactions should not be ignored. There are a lack of reports on G × E for temperament in AMS vs. conventional milking systems, grazing vs. confinement, and small-holders vs. intensive and large-scale farms. However, Van der Laak et al. (2016) reported no G × E for milking temperament between farms with grazing or indoor production systems in the Netherlands.

Selection indexes are usually derived based on economic values, which are considered as the marginal value of one unit change in the respective trait. Economic values are calculated based on a bioeconomic model by computing the production profit. The main economic and welfare losses of temperamental cows are a reduction in management efficiency (increased labor) and injuring themselves or human handlers. Additionally, temperament is associated with other functional traits, including longevity, health, and milkability. For instance, Holstein, Jersey, and Ayrshire cows with unfavorable temperament score were found to have shorter functional longevity when compared to calm cows (Sewalem et al., 2010). As discussed before, temperament influences capacity and efficiency of AMS, which has direct economic implications. However, the difficulty to quantify the economic value of temperament has limited its incorporation in dairy cattle breeding programs. The economic weights for temperament in the NTM and APR are based on determining the amount of extra labor for each temperament score unit or on the expected changes in labor requirements due to variation in the proportion of problematic cows in the population (Byrne et al., 2016). However, labor costs in China are usually low, which translates in relatively low economic value for temperament. The definition of novel and more accurate phenotypes coupled with genomic selection is likely to play a major role on the improvement of dairy cattle temperament. For instance, in Canada a substantial genetic progress for milking temperament has been achieved, that is, >0.60 units after the introduction of genomics (CDN, 2019).

Conclusions

Temperament in dairy cattle is moderately heritable and genetically correlated with milkability, health, longevity, and reproduction traits. The currently collected phenotypes are moderately repeatable, indicating the need to collect multiple records on each individual. It is still challenging to estimate the economic value of temperament and therefore, its inclusion in breeding programs. There is undergoing research in the area of temperament phenomics and various new measurement alternatives are being investigated, including video-imaging, pedometers, activity-collars, and AMS-derived traits. We expect that over the next few decades, there will be a greater focus on genomic selection for functional traits and temperament based on refined phenotypes will be a major one.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at Animal Frontiers online.

About the Author

Yao Chang is a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of Animal Genetics, Breeding and Reproduction Science at China Agriculture University. She earned a Bachelor of Agriculture from China Agriculture University. Her research interests include 1) molecular quantitative genetics of dairy cattle temperament traits and 2) genetic selection for growth traits in both dairy and beef cattle.

Luiz F. Brito is an Assistant Professor of Quantitative Genetics and Genomics in the Department of Animal Sciences at Purdue University (Indiana, USA). He also holds an Adjunct Faculty position in the Department of Animal Biosciences at the University of Guelph (Canada). Luiz earned a BSc degree (with distinction) in Animal Sciences and a MSc in Genetics and Animal Breeding at the Federal University of Viçosa (Brazil). He completed his PhD and a postdoctoral fellowship at the Centre for Genetic Improvement of Livestock, University of Guelph (Canada). Luiz is broadly interested in quantitative genetics, genomics, and systems biology applied to genetic improvement of livestock species. His research group focuses on genetics and genomics of complex traits associated with animal behavior and welfare, environmental efficiency, and adaptation to challenging environments.

Amanda Botelho Alvarenga is a PhD student in Quantitative Genetics and Genomics in the Department of Animal Sciences at Purdue University, USA. Amanda has an honors BSc degree in Animal Science from the Federal University of Lavras, Brazil. She completed her MSc in Genetics and Animal Breeding at the “Luiz de Queiroz” College of Agriculture, University of São Paulo, Brazil. She is interested in statistics, quantitative genetics, and genomics applied to genetic improvement of livestock species. Her current PhD project focuses on integrating multiple data sources to maximize the performance of genomic predictions for temperament traits in American Angus cattle.

Yachun Wang is a Professor in the College of Animal Science & Technology at the China Agricultural University, China. She earned a PhD in Animal Genetics and Breeding from the University of Guelph. Before her current position, she worked for 8 yr as a research assistant in the Beijing Institute of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine at the Chinese Academy of Agriculture Science. She is a member of the genetic evaluation team for the Chinese dairy and beef industry. Her current research interests include: 1) refining the China Performance Index (CPI/GCPI) to include reproduction traits; 2) genetic and genomic evaluation of reproduction traits using joint Chinese and Danish training populations, and 3) quantifying the effect of heat stress on Chinese dairy cattle performance, as well as genetic mechanism of heat stress and cold stress in cattle. Corresponding author: wangyachun@cau.edu.cn

Funding

Yachun Wang acknowledges financial support from the China Agriculture Research System (Grant number: CARS-36), the Program for Changjiang Scholar and Innovation Research Team in University (Grant number: IRT_15R62), Beijing Sanyuan Breeding Technology (Grant number: SYZYZ20190005), and National Agricultural Genetic Improvement Program (Grant number: 2130135).

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- AnimalQTLdb. 2019. Cattle QTL Database. Available from https://www.animalgenome.org/cgi-bin/QTLdb/BT/index

- Barkema H.W., von Keyserlingk M.A., Kastelic J.P., Lam T.J., Luby C., Roy J.P., LeBlanc S.J., Keefe G.P., and Kelton D.F.. . 2015. Invited review: changes in the dairy industry affecting dairy cattle health and welfare. J. Dairy Sci. 98:7426–7445. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-9377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand B., Hadlich F., Brandt B., Schauer N., Graunke K.L., Langbein J., Repsilber D., Ponsuksili S., and Schwerin M.. . 2015. Temperament type specific metabolite profiles of the prefrontal cortex and serum in cattle. PLoS One 10:e0125044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne T.J., Santos B.F.S., Amer P.R., Martin-Collado D., Pryce J.E., and Axford M.. . 2016. New breeding objectives and selection indices for the Australian dairy industry. J. Dairy Sci. 99:8146–8167. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDN. 2019. 10 Years of Genomic Selection: What’s Next? Available from https://www.cdn.ca/document. php?id=530

- Chang Y., Li X., Zhang H.L., Qi J.G., Guo G., Liu L., and Wang Y.C.. . 2019. Genetic analysis for temperament in holstein cattle in Beijing area. Acta Vet. Zootech. Sin. 50(4):712–720. [Google Scholar]

- Cue R.I., Harris B.L., and Rendel J.M.. . 1996. Genetic parameters for traits other than production in purebred and crossbred New Zealand dairy cattle. Livest. Prod. Sci. 45(2):123–135. doi: 10.1016/0301-6226(96)00009-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DAC. 2019. China dairy statistical summary. Beijing: Dairy Association of China. [Google Scholar]

- Erf D.F., Hansen L.B., and Lawstuen D.A.. . 1992. Inheritance and relationships of workability traits and yield for holsteins1. J. Dairy Sci. 75(7):1999–2007. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)77959-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foris B., Zebunke M., Langbein J., and Melzer N.. . 2018. Evaluating the temporal and situational consistency of personality traits in adult dairy cattle. PLoS One 13:e0204619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich J., Brand B., Ponsuksili S., Graunke K.L., Langbein J., Knaust J., Kühn C., and Schwerin M.. . 2016. Detection of genetic variants affecting cattle behaviour and their impact on milk production: a genome-wide association study. Anim. Genet. 47:12–18. doi: 10.1111/age.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geburt K., Piechotta M., König von Borstel U., and Gauly M.. . 2015. Influence of testosterone on the docility of German Simmental and Charolais heifers during behavior tests. Physiol. Behav. 141:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons J.M., Lawrence A.B., and Haskell M.J.. . 2011. Consistency of flight speed and response to restraint in a crush in dairy cattle. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 131(1–2):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Gil B., Ball N., Burton D., Haskell M., Williams J.L., and Wiener P.. . 2008. Identification of quantitative trait loci affecting cattle temperament. J. Hered. 99:629–638. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esn060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiendleder S. 2003. Mapping of QTL for body conformation and behavior in cattle. J. Hered. 94(6):496–506. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esg090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbehdari D., Wang Z., Grant J.R., Murdoch B., Prasad A., Xiu Z., Marques E., Stothard P., and Moore S.S.. . 2008. A whole-genome scan to map quantitative trait loci for conformation and functional traits in Canadian Holstein bulls. J. Dairy Sci. 91:2844–2856. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács L., Kézér F.L., Kulcsár-Huszenicza M., Ruff F., Szenci O., and Jurkovich V.. . 2016. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and cardiac autonomic responses to transrectal examination differ with behavioral reactivity in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 99(9):7444–7457. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M., Erbe M., Bapst B., Bieber A., and Simianer H.. . 2013. Estimation of genetic parameters for novel functional traits in Brown Swiss cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 96:5954–5964. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-6236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laak M., van Pelt M.L., de Jong G., and Mulder H.A.. . 2016. Genotype by environment interaction for production, somatic cell score, workability, and conformation traits in Dutch Holstein-Friesian cows between farms with or without grazing. J. Dairy Sci. 99:4496–4503. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansade L., Bouissou M., and Erhard H.W.. . 2008. Reactivity to isolation and association with conspecifics: a temperament trait stable across time and situations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 109(2–4):355–373. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2007.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell D., Arave C.W., and Walters J.L.. . 1988. Relationship of three measures of behavior to milk production. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 21(4):307–313. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(88)90065-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Réale D., Reader S.M., Sol D., McDougall P.T., and Dingemanse N.J.. . 2007. Integrating animal temperament within ecology and evolution. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 82:291–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandgren C., and Emanuelson U.. . 2017. Is there an ideal automatic milking system cow and is she different from an ideal parlormilked cow? In Proceedings of the National Mastitis Council 56th Annual Meeting, At St. Pete Beach, Florida, USA; New Prague, MN; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Santos L.V., Brügemann K., Ebinghaus A., and König S.. . 2018. Genetic parameters for longitudinal behavior and health indicator traits generated in automatic milking systems. Arch. Anim. Breed. 61(2): 161–171. doi: 10.5194/aab-61-161-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sewalem A., Miglior F., and Kistemaker G.J.. . 2010. Analysis of the relationship between workability traits and functional longevity in Canadian dairy breeds. J. Dairy. Sci. 93(9):4359–4365. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewalem A., Miglior F., and Kistemaker G.J.. . 2011. Short communication: genetic parameters of milking temperament and milking speed in Canadian Holsteins. J. Dairy. Sci. 94(1):512–516. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephansen R.S., Fogh A., and Norberg E.. . 2018. Genetic parameters for handling and milking temperament in Danish first-parity Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 101:11033–11039. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-14804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland M.A., and Dowling S.K.. . 2014. The relationship between responsiveness of first-lactation heifers to humans and the behavioral response to milking and milk production measures. J. Vet. Beh. 9(1):30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2013.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbrook A.J., Hemsworth P.H., Barnett J.L., and Skinner A.. . 1989. An investigation of the social-behavior and response to humans of young cattle. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 23(1–2):107–116. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(89)90011-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tine. 2017. Statistikksamling fra kuog geitekontrollen 2017. Available from https://medlem.tine.no/aktuelt/nyheter/hk-statistikker/statistikksamling2017

- Visscher P.M., and Goddard M.E.. . 1995. Genetic parameters for milk yield, survival, workability, and type traits for Australian dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 78:205–220. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(95)76630-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wethal K.B., and Heringstad B.. . 2019. Genetic analyses of novel temperament and milkability traits in Norwegian Red cattle based on data from automatic milking systems. J. Dairy Sci. 102:8221–8233. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-16625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.