Abstract

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is an immunologically mediated inflammatory disease of the central nervous system that typically occurs after a viral infection or recent vaccination, and is most commonly seen in the pediatric population. In 2007 the International Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Study Group proposed a consensus definition for ADEM for application in research and clinical settings. This article gives an overview of ADEM in children, focusing on differences that have emerged since the consensus definition was established. Although the focus is on neuroimaging in these patients, a synopsis of the clinical features, immunopathogenesis, treatment, and prognosis of ADEM is provided.

Keywords: Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, Consensus guidelines, Molecular mimicry, Inflammatory cascade

Key points

-

•

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) typically occurs after a viral infection or recent vaccination.

-

•

ADEM can represent a diagnostic challenge for clinicians, as many disorders (inflammatory and noninflammatory) have a similar clinical and radiologic presentation.

-

•

The differential diagnosis for multifocal hyperintense lesions on neuroimaging includes an exhaustive list of potential mimickers, namely infectious, inflammatory, rheumatologic, metabolic, nutritional, and degenerative entities.

Introduction

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is an immunologically mediated inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS) resulting in multifocal demyelinating lesions affecting the gray and white matter of the brain and spinal cord. ADEM is characteristically a monophasic illness that is commonly associated with an antigenic challenge (febrile illness or vaccination), which is believed to function as a trigger to the inflammatory response underlying the disease. It is most commonly seen in the pediatric population, but can occur at any age.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Symptoms are highly dependent on the area of the CNS affected, but are polyfocal in nature. Common symptoms include hemiparesis, cranial nerve palsy, seizures, cerebellar ataxia, and hypotonia.3, 7, 8, 9 The diagnosis of ADEM depends on the history, physical examination, and supplemental neuroimaging.

Despite the long-standing recognition of ADEM as a specific entity, no consensus definition of ADEM had been reached until recently. Historically, different definitions of ADEM have been used in published cases of pediatric and adult patients, which varied as to whether events required (1) monofocal or multifocal clinical features, (2) a change in mental status, and (3) a documentation of previous infection or immunization.3, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 To avoid further misdiagnosis and to develop a uniform classification, the International Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Study Group18 proposed a consensus definition for ADEM for application in both research and clinical settings (Box 1 ). One of the most significant changes proposed by this definition was the mandatory inclusion of encephalopathy as a clinical symptom in patients presenting with ADEM. Before the development of the consensus definition, although encephalopathy was included in the clinical description it was not considered an essential criterion for the diagnosis. Thus, many of the previous studies investigating the clinical and radiologic features of pediatric ADEM were performed on patients who may no longer meet the consensus criteria, and may have led to the classification of other neurologic disorders as ADEM (Table 1 ). It may be that there is an inherent difference in the patients who present with multifocal symptoms and encephalopathy as opposed to those without encephalopathy; therefore, this distinction is imperative. Because of the lack of uniform description and clear clinical and neuroimaging diagnostic criteria in ADEM, caution must be exercised when applying previous clinical and radiologic descriptions of patients with this disorder.

Box 1. International MS Study Group monophasic ADEM criteria.

-

•

No history of prior demyelinating event

-

•

First clinical event with presumed inflammatory or demyelinating cause

-

•

Acute or subacute onset

-

•

Affects multifocal areas of central nervous system

-

•

Must be polysymptomatic

-

•

Must include encephalopathy (ie, behavioral change or altered level of consciousness)

-

•

Neuroimaging shows focal/multifocal lesion(s) predominantly affecting white matter

-

•

No neuroimaging evidence of previous destructive white matter changes

-

•

Event should be followed by clinical/radiologic improvements (although may be residual deficits)

-

•

No other etiology can explain the event

-

•

New or fluctuating symptoms, signs, or magnetic resonance imaging findings occurring within 3 months are considered part of the acute event

Data from Krupp LB, Banwell B, Tenembaum S. Consensus definitions proposed for pediatric multiple sclerosis and related disorders. Neurology 2007;68:S7–12.

Table 1.

Summary of the lesion characterization in previous pediatric ADEM cohorts within the last 10 years

| Authors,Ref. Year | N | New Criteriaa (%) | White Matter (%) |

Gray Matter (%) |

Brainstem (%) | Cerebellum (%) | Enhancingb (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep | Juxt | Peri | CC | Cort | BG | Thal | ||||||

| Hynson et al,9 2001 | 31 | 68 | 90 | 29 | 29 | 61 | 39 | 32 | 42 | — | 8/28 | |

| Tenembaum et al,13 2002 | 84 | 69 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 12 | — | — | 8/27 |

| Murthy et al,12 2002 | 18 | 44 | 100 8.0c (1–30) |

— | 60 2.5c (0–16) |

7 0.1c (0–1) |

80 4.9c (0–28) |

20 0.3c (0–2) |

27 0.3c (0–2) |

47 1.1c (0–8) |

13 0.1c (0–1) |

4/15 |

| Anlar et al,14 2003 | 33 | 48 | 42 | 12 | 12 | — | 45 | — | 45 | 42 | 2/31 | |

| Richer et al,19 2005 | 10 | 40 | 90 | — | 30 | 80 | — | 60 | 50 | 3/9 | ||

| Madan et al,20 2005 | 7 | 43 | 86 | — | — | — | — | 43 | 14 | 14 | 14 | — |

| Singhi et al,21 2006 | 52 | 56 | 54 | — | 19 | 13 | — | 17 | 30 | 17 | 26 | — |

| Mikaeloff et al,22 2007 | 108 | 100 | — | 61 | 42 (>2) | — | 18 | 58 | 63 | 14/85 | ||

| Atzori et al,23 2009 | 20 | 65 | — | 60 | 20 | 5 | 15 | 50 | 60 | 10/14 | ||

| Alper et al,24 2009 | 24 | 42 | 68 | 21 | 18 | 9 | — | 43 | 41 | 50 | — | |

| Callen et al,25 2009 | 20 | 100 | 80 | 90 | 65 | 80 | 80 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 5/11 | |

| Visudtibhan et al,26 2010 | 16 | 100 | 75 | 19 | 75 | — | 19 | 50 | 50 | 25 | — | |

| Pavone et al,7 2010 | 17 | 100 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 23 | — | — | 3/17 |

Abbreviations: BG, basal ganglia; CC, callosal; Cort, cortical gray matter; Juxt, juxtacortical; Peri, periventricular; Thal, thalamic.

Consensus criteria of International Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Society.18

Number of patients showing enhancing lesions (numerator) over the number of study patients who received contrast (denominator).

Mean lesion count in category and minimum and maximum lesion counts (in parentheses).

This review is intended to give an overview of ADEM in the pediatric population, focusing on differences that have emerged since the consensus definition was established. Although the focus is on neuroimaging in these patients, a synopsis of the clinical features, immunopathogenesis, treatment, and prognosis of ADEM is provided.

Epidemiology and clinical presentation

Considering that the diagnostic criteria for ADEM were not elucidated before 2007, the annual incidence rate and prevalence within the population is not precisely known. In addition, no analyses of worldwide distribution of ADEM have been completed; therefore, the reported prevalence and incidence taken within a single area may not be generalizable to the population as a whole. Before 2007, the prevalence of ADEM within the pediatric population was estimated at 0.8 to 1.1 per 100,000 in those younger than 10 years.6, 7 A study by Leake and colleagues11 evaluated the incidence of ADEM in San Diego County, USA. The investigators estimated this to be 0.4 per 100,000 per year in those younger than 20 years. More recent studies completed after the definition of ADEM had been established have suggested that these rates may actually be higher. Visudtibhan and colleagues26 reported the prevalence of children with definite ADEM in Bangkok, Thailand to be 4.1 per 100,000. Another study from Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan reported the annual incidence to be 0.64 per 100,000.27 The overall frequency of ADEM in Canadian children with acquired demyelinating disorders had been estimated at 22%.28

Although ADEM may present at any age, it is most frequently described in the pediatric population. The mean age of onset in the pediatric population is reported to be 7.4 ± 1.3 years of age and the median age of onset is 8 years, according to a recent meta-analysis.7 However, 12 of the 13 studies included in the analysis were performed before the revised ADEM definition.3, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 29, 30, 31 More recent studies using the new criteria for ADEM have shown a similar mean age of onset, ranging from 5.7 to 7.6 years.22, 25, 27 An equal sex distribution was previously suggested,6, 8, 11 but more current studies show a slight male preponderance (1.4–2.3:1) in patients presenting with ADEM at.7, 22, 25, 27 A seasonal distribution of ADEM has been described, with an increased number of cases during the winter and spring months.8, 11, 12

ADEM typically occurs after a viral infection or recent vaccination. The frequency with which a preceding febrile illness is noted has widely varied in previous literature, ranging from 46% to 100%.3, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 22, 32 This variation is likely attributable to the lack of uniform diagnostic criteria, with some investigators using the term ADEM only when a preceding febrile illness has been documented, as well as different latency periods from febrile illness to ADEM being deemed clinically significant. A recent meta-analysis showed that a preceding triggering event occurred in 69% of 492 patients diagnosed with ADEM.7 The most common preceding trigger is a nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection.13 The duration between antigenic challenge and the first signs and symptoms of ADEM has been cited as ranging from 1 to 28 days with a mean of 6 to 12 days.7, 13, 26, 33, 34 Pavone and colleagues7 showed different latency periods depending on the triggering factor, with the shortest latency being seen for upper respiratory tract infections or gastroenteritis (2–4 days). Although a link between viral illness and ADEM is likely, it should be noted that there is a high frequency of viral episodes in childhood, and medical history is often positive regardless of whether a causal correlation exists.

The neurologic features of ADEM are often seen following a short prodromal phase consisting of fever, malaise, headache, nausea, or vomiting. Patients subsequently develop neurologic symptoms subacutely, within a mean period of 4.5 to 7.5 days (range: 1–45 days).7, 13 Occasionally there is rapid progression of symptoms and signs to coma and/or decerebrate posturing.3 The clinical presentation of ADEM is widely variable, with the type and severity clinical features being determined by the distribution of lesions within the CNS. Although studies have previously reported an encephalopathy in 21% to 74% of patients3, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 33, 35 (with only 55% having altered mental status in a recent meta-analysis7), application of the new diagnostic criteria mandates that encephalopathy (either behavioral change or altered mental status) be present in 100% of cases. It should thus be noted that previous studies looking at the presenting signs and symptoms encompass patients who, today, would not meet diagnostic criteria for ADEM. With that in mind, the neurologic features that have previously been noted in ADEM include: unilateral or bilateral pyramidal signs (60%–95%); cranial nerve palsies (22%–89%); hemiparesis (76%–79%); ataxia (18%–65%); hypotonia (34%–47%); seizures (10%–47%); visual loss due to optic neuritis (7%–23%); and speech impairment (5%–21%).3, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17 Peripheral nervous system involvement has been reported in the adult cohort (with frequencies up to 43.6% of patients), but is considered rare in childhood ADEM patients.35, 36, 37, 38

Only 2 studies have looked at presenting signs and symptoms of patients with ADEM according to the new consensus definitions. Mikaeloff and colleagues22 reported that 79% presented with long tract dysfunction, 48% presented with brainstem dysfunction, 32% presented with seizures, and 6% presented with optic neuritis. Pavone and colleagues7 found the following signs and symptoms: ataxia (47%), hypotonia (41%), seizures (29%), thalamic syndrome (23%), hemiparesis (23%), cranial nerve palsy (18%), headache (18%), fever (12%), and ptosis (6%).

Respiratory failure secondary to brainstem involvement or severely impaired consciousness has been reported in 11% to 16% of patients in previous studies.13, 39 In a study where all children met the consensus definition of ADEM, the numbers of patients with respiratory failure were strikingly similar (11%).7 A recent study investigating the necessity of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions for patients with ADEM found that 25% of patients with ADEM required an ICU admission, with an incidence of 0.5 per million children per year.40 Rates of ICU admission may be higher than previously expected, considering the mandatory inclusion of altered mental status. In the study by Pavone and colleagues,7 ICU admissions were necessary in 41% of patients with ADEM at some point during their clinical course.

Immunopathogenesis

The precise mechanisms implicated in ADEM are not well known, and the relationship between the pathogenesis of ADEM and MS continues to remain a matter of controversy. There is a general consensus that ADEM is an immune-mediated disorder resulting from an autoimmune reaction to myelin.5 An autoimmune pathogenesis is supported by the pathologic similarities between ADEM and the experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) model,41, 42 which is a demyelinating disease that may be induced in a variety of animal species after immunization with myelin proteins or peptides.

There are 2 basic mechanisms proposed to cause ADEM,5 both of which rely on the exposure of the immune system to an antigenic challenge (ie, viral, bacterial, or exposure to degradation products via immunization):

-

1.

Molecular mimicry theory.43 This theory relies on the idea that myelin antigens (for example, myelin basic protein [MBP], proteolipid protein, and myelin oligodendrocyte protein) could share a structural similarity with antigenic determinants on the infecting pathogen. The infected host mounts an immune response producing antiviral antibodies that are thought to cross-react with myelin antigens that share a similar structure, inadvertently producing an autoimmune response. Myelin proteins have shown resemblance to several viral sequences, and cross-reactivity of immune cells has been demonstrated in several studies. T cells to human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6),44 coronavirus,45 influenza virus,46 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)47 have been shown to cross-react with MBP antigens. Furthermore, enhanced MBP reactive T-cell responses have been demonstrated in patients with postinfectious ADEM,48, 49 and enhanced anti-MBP antibodies have been shown in patients with postvaccinial ADEM following vaccination with Semple rabies vaccine.50, 51

-

2.

Inflammatory cascade theory. Nervous system tissue is thought to be damaged secondary to viral infection, resulting in the leakage of myelin-based antigens into the systemic circulation through an impaired blood-brain barrier.5 These antigens promote a T-cell response after processing in the lymphatic organs, which in turn causes secondary damage to the nervous system tissue through an inflammatory response.5 This theory is supported by the Theiler murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelinating disease model,52 which is a biphasic disease of the CNS whereby direct infection of neurotropic TMEV picornavirus results in an initial CNS injury followed by a secondary autoimmune response.53, 54 However, this model has been criticized for its superficial resemblance to ADEM, as ADEM is not thought to be due to a direct viral infection of the CNS. It is more likely that the nervous system tissue damage proposed by this theory is indirect, through the release of multiple cytokines and chemokines in response to the initial infection. The role of chemokines, particularly interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor α, and matrix metalloproteinase 9, have been hypothesized to play a role in ADEM,55, 56 and the spectrum of chemokines found to be elevated in ADEM may differ from that in MS.57

As expected by the currently proposed mechanisms discussed here, ADEM is frequently preceded by an infection or recent vaccination.58 However, in most cases investigations fail to identify the precise infectious agent responsible.3 Viruses that have been implicated in promoting the immune response responsible for ADEM include herpes simplex virus, human immunodeficiency virus, HHV-6, mumps, measles, rubella, varicella, influenza, enterovirus, hepatitis A, coxsackie, EBV, and cytomegalovirus.59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 It has been proposed that the risk of ADEM is highest with measles and rubella, with the risk after infection with these viruses being 1:1000 and 1:20,000, respectively.71 Other infectious agents that have been linked to ADEM include group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infection,72, 73 pertussis,74 Mycoplasma pneumonia,75, 76 Borrelia burgdorferi,77 Legionella,75, 78 Rickettsiae,79 and Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria.80

Approximately 5% to 12% of patients with ADEM have a history of vaccination within the month before presentation.11, 13 The only vaccination that has been epidemiologically and pathologically proven to be associated with ADEM is the Semple form of the rabies vaccine.81, 82 Other vaccinations that have been reported to have a temporal association with the onset of ADEM include hepatitis B, pertussis, smallpox, diphtheria, measles, mumps, rubella, human papilloma virus, pneumococcus, varicella, influenza, Japanese B encephalitis, polio, and meningococcal A and C.11, 13, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94 The rates at which these vaccinations are reported to cause ADEM are: 1 to 2 per million for measles94; 1 in 3000 to 1 in 7000 for Semple rabies81; 1 in 25,000 for duck embryo rabies95; less than 1 in 75,0000 for nonneural human diploid cell rabies93; 0.2 per 100,000 for inactivated mouse brain–derived Japanese B encephalitis87; 3 in 665,000 for smallpox83; and 0.9 per 100,000 for diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus.94 On rare occasions ADEM has been also reported following organ transplantation.96, 97

Recently, studies have investigated the role of genetics in predisposing patients to ADEM. Multiple human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles have been found to occur at a higher frequency in patients with ADEM, including HLA-DRB1*1501, HLA-DRB5*0101, HLA-DRBQ*1503, HLA-DQA1*0102, HLA-DQB1*0602, HLA-DRB1*01, HLA-DRB*03, and HLA-DPA1*0301.17, 98, 99 The exact frequency of expression of these alleles and their future clinical utility in ADEM is currently unknown.

Laboratory findings

Laboratory findings are useful for ADEM, mainly to rule out other causes for the patient’s presenting symptoms. Despite ADEM patients commonly reporting a recent infection before their neurologic presentation, only 17% have evidence of a recent infection on serology.13

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is normal in up to 61.5% of patients with ADEM.3, 7 If patients are found to have abnormal CSF parameters, they are usually minor and nonspecific. A lymphocyte pleocytosis (usually between 50 and 180 cells/mm2) and elevated protein (commonly 0.5–1.0 g/dL) can be seen.7, 13, 22 Rarely a mild increase in glucose has been noted.7 Oligoclonal bands, which are commonly positive in patients with MS, are less frequently observed in patients with ADEM (seen in 0%–29%).3, 7, 9, 13, 18, 22, 100, 101 Elevations in immunoglobulins have been reported in up to 13% of patients.13

An electroencephalogram (EEG) may be completed as part of the workup of a patient with ADEM following a presentation with seizures or to rule out nonconvulsive status epilepticus as a cause of the accompanying encephalopathy. Although 78% of patients with ADEM have a diffusely slow background (consistent with encephalopathy), focal slowing (10%) or focal epileptiform discharges (2%) may be seen.13 EEG is seldom useful in establishing diagnosis.

Evoked potentials (including visual evoked potentials, brainstem auditory evoked potentials, and somatosensory evoked potentials) may be normal, depending on the location of brain lesions. Abnormal visual evoked potentials have been reported in up to 12% of patients.7

Neuroimaging

Computed Tomography of the Brain

There are few studies that comment on computed tomography (CT) findings in patients with ADEM, namely because these patients are more commonly imaged with more sensitive imaging modalities, in addition to the concern of radiation exposure in the pediatric population. Most studies indicate that CT is unrevealing when completed early in the disease and that this imaging modality is insensitive for smaller demyelinating lesions.3, 5, 34 The most commonly reported abnormalities are discrete hypodense areas within cerebral white matter and juxtacortical areas.7, 13 However, some investigators have reported high rates of CT-scan abnormalities in patients with ADEM. Tenembaum and colleagues13 reported abnormal findings in 78% of patients after a mean interval of 6.5 days from symptom onset. In an article by Pavone and colleagues,7 where all patients met the new consensus criteria for ADEM, abnormal CT scans were reported in 86% of their patients when performed after a mean interval of 2.5 days from initial neurologic presentation.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain and Spine

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the brain is the most important paraclinical tool available to aid in the diagnosis of ADEM and to distinguish the clinical presentation from other inflammatory and noninflammatory neurologic diseases. Since the advent of MR imaging, many studies have evaluated the radiologic appearance of ADEM in children and adults.2, 5, 7, 9, 12, 13, 14, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 34, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110 From the listed studies, the typical MR imaging findings described in ADEM are widespread, bilateral, asymmetric patchy areas of homogeneous or slightly inhomogeneous increased signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging within the white matter, deep gray nuclei, and spinal cord. Within the white matter, juxtacortical and deep white matter is involved more frequently than is periventricular white matter, which is an important contrast to patients with MS. In addition, lesions involving the corpus callosum, which are considered typical in MS, are rarely seen in ADEM. Infratentorial lesions are common, including the brainstem and cerebellar white matter. With respect to lesion size and morphology, variation is seen, ranging from small, round lesions to large, amorphous, and irregular lesions. Unenhanced T1-weighted images reveal that lesions are typically inconspicuous unless the lesions are large, in which case a faint hypodensity is seen within the affected areas. These lesions typically appear simultaneously with clinical presentation. However, delayed appearance of abnormalities up to 1 month after clinical onset has been described, so a normal MR image within the first days after symptom onset suggestive of ADEM does not exclude the diagnosis. Contrast enhancement in ADEM is variable and has been reported in 30% to 100% of patients with ADEM, in nonspecific patterns (nodular, diffuse, gyral, complete, or incomplete ring).

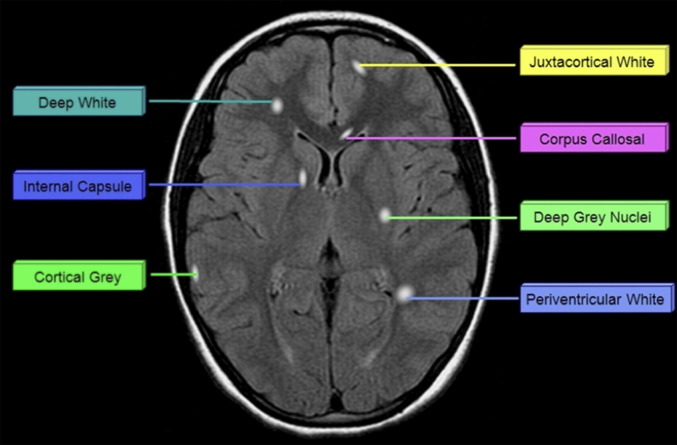

In the past 10 years, only 4 studies have described the MR imaging appearance of cohorts of children who uniformly meet the current consensus criteria for ADEM. A summary of the neuroimaging findings of selected studies completed within the last 10 years is presented in Table 1. Fig. 1 displays the potential location sites for demyelination as described below.

Fig. 1.

Potential location of lesions in patients with acquired demyelination.

Mikaeloff and colleagues22 qualitatively described the radiologic appearance of 108 children with monophasic ADEM. In their cohort, juxtacortical white matter, deep gray matter, and infratentorial structures were affected with approximately 60% frequency. Lesions were less commonly seen in periventricular white matter, cortical gray matter (18%), and spinal cord (12%). Deep white matter lesions and cerebellar lesions were not specifically described, thus their frequency of involvement cannot be commented on. Almost half of the children in their cohort had at least 9 lesions, but comprehensive lesion counts were not reported. Bilateral lesions were described in 81% of their patient cohort. “Large lesions” (>2 cm) were present in 72% of cases, but there was no comment made about other lesion sizes. Nearly half of their patients met at least 3 Barkoff criteria. Of the patients who received gadolinium, only 16% displayed enhancing lesions. However, there was no comment about the pattern of enhancement.

A smaller study was more recently published by Vistudtibhan and colleagues.26 Although 16 patients met the initial criteria for ADEM, 3 of these patients subsequently fulfilled criteria for relapsing-remitting MS. Based on the reported imaging characteristics described for the remaining 13 patients with monophasic ADEM, the brain region most commonly involved was the subcortical/periventricular region (88%). A distinction was not made between subcortical lesions and periventricular lesions, which would have been useful considering that the literature seems to favor periventricular lesions as being more characteristic of MS in comparison with ADEM.25, 111 Similar to the results from Mikaeloff and colleagues,22 brainstem and deep gray nuclei were also commonly affected, with a frequency of 69% and 50%, respectively. Lesions involving cortex and juxtacortex were seen less frequently (31%); however, there was no distinction made between these 2 areas. The cerebellum was involved in approximately one-third of the patients. Spinal cord involvement was much higher than that reported by Mikaeloff and colleagues,22 with a frequency of approximately 60%. There was no comment made about lesion size, nor the frequency of gadolinium enhancement.

Data from the authors’ group was published in 2009.25 The characteristics of lesions in 20 children with monophasic ADEM were quantitatively assessed. When the data are viewed qualitatively (ie, displaying the number of patients having at least 1 lesion in any given location), lesions appear to be relatively common in all regions of the brain. However, when the mean lesion counts are evaluated for each region (Table 2 ), a difference in the lesion distribution is apparent. Similar to the findings by Mikaeloff and colleagues22 and Vistudtibhan and colleagues,26 lesions were more commonly seen in the deep white matter and juxtacortical white matter than in the periventricular white matter. In contrast to the previous studies by both groups, lesions were commonly found to impinge on the cortical ribbon. Another consistent result between all 3 studies was the frequent involvement of the deep gray nuclei. Although the mean lesion count was only 2.5, only 30% of the patients had no deep gray involvement. Infratentorial regions were commonly involved, as reported in the other studies, but the mean lesion counts in these regions were low. With respect to lesion size, small (<1 cm axial, <1.5 cm longitudinal) and medium (1–2 cm axial, 1.5–2.5 cm longitudinal) lesions were found in all patients, but 70% also had large (>2 cm axial, >2.5 cm longitudinal) lesions. This amount is nearly identical to the number of “large lesions” seen by Mikaeloff and colleagues.22 Finally, only 11 of the authors’ patients received gadolinium, 5 of whom (45%) displayed enhancement.

Table 2.

Quantitative lesion parameters in children with ADEM from Callen and colleagues25

| Lesion Counts |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Minimuma | Maximum | |

| Deep white matter | 6.8 | 0 (4) | 29 |

| Juxtacortical white matter | 9.7 | 0 (2) | 38 |

| Periventricular white matter | 1.4 | 0 (9) | 10 |

| Callosal white matter | 1.1 | 0 (7) | 4 |

| Cortical gray matter | 7.5 | 0 (4) | 35 |

| Deep gray matter | 2.6 | 0 (6) | 8 |

| Brainstem | 1.7 | 0 (6) | 6 |

| Cerebellar | 0.8 | 0 (11) | 4 |

| Small | 15.8 | 2 | 41 |

| Medium | 5.6 | 0 (3) | 18 |

| Large | 3.5 | 0 (6) | 18 |

| Total | 24.8 | 3 | 62 |

Small: <1 cm axial, <1.5 cm longitudinal; Medium: 1–2 cm axial, 1.5–2.5 cm longitudinal; Large: >2 cm axial, >2.5 cm longitudinal.

Number in parentheses represents the number of children with ADEM (n = 20) who had zero lesions in this category.

Data from Callen DJ, Shroff MM, Branson HM, et al. Role of MRI in the differentiation of ADEM from MS in children. Neurology 2009;72:968–73.

In addition to describing lesion characteristics, many investigators have previously attempted to divide patients into groups showing similar radiologic features. Application of these classification criteria to the authors’ cohort has proved to be unsuccessful. Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5 display the variety of lesion patterns displayed in selected cases of this patient population. When one considers the multitude of causes that have been reported to produce an ADEM phenotype, the lack of a consistent pattern is not surprising. However, despite the lack of subgroups, there do appear to be some consistent radiologic findings in ADEM (Box 2 ).

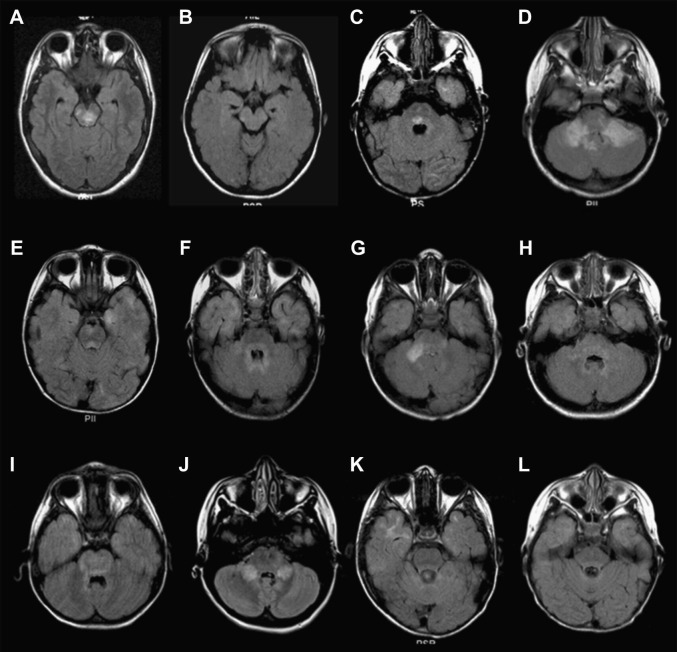

Fig. 2.

(A–L) Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images through the infratentorial regions of 12 children with ADEM.

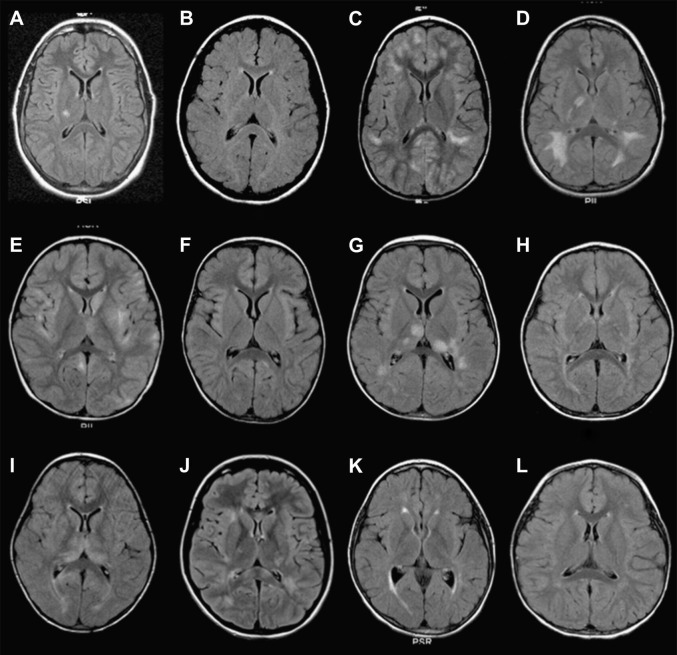

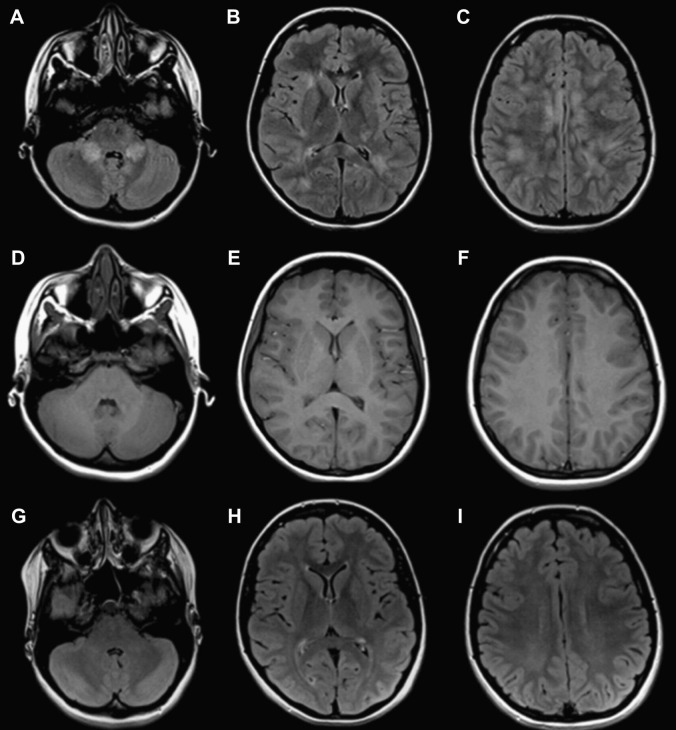

Fig. 3.

(A–L) Axial FLAIR images at the level of the basal ganglia and thalamus of 12 children with ADEM.

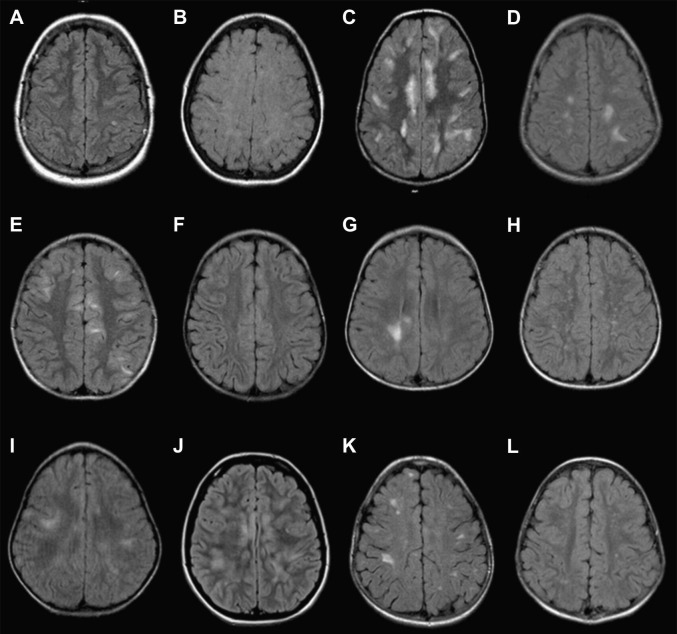

Fig. 4.

(A–L) Axial FLAIR images through the cerebral convexities of 12 children with ADEM.

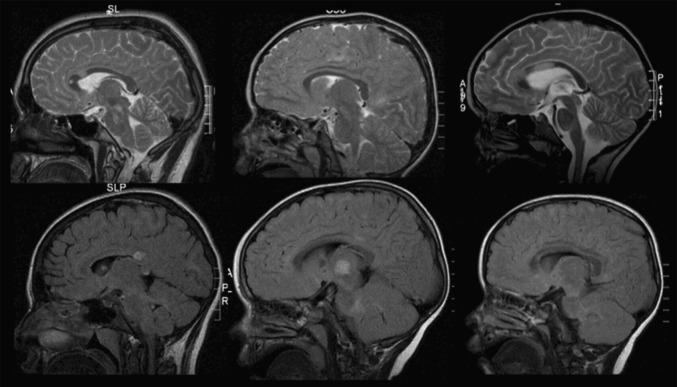

Fig. 5.

Mid/Paramidsagittal T2-weighted and FLAIR images of 6 children with ADEM.

Box 2. Proposed commonalities in ADEM MR imaging appearance.

-

•

Bilateral asymmetric/symmetric involvement (rarely unilateral)

-

•

White matter > gray matter, but usually both affected

-

•

Deep/juxtacortical white matter > periventricular white matter

-

•

Both supratentorial and infratentorial lesions (less commonly either/or)

-

•

Small > medium > large, but often all sizes are present in same patient

-

•

Variable contrast enhancement

Most recently, a prospective study published by Pavone and colleagues7 described the radiologic appearance of 17 patients with ADEM. It should be noted that patients who were included before 1998 received imaging on a 0.5-T machine, whereas those after 1998 received imaging on a 1.5-T machine. The patients were classified according to the pattern of abnormalities seen on MR imaging into the following groups previously described by Tenembaum and colleagues13: ADEM with large, confluent, or tumefactive lesions (23%); ADEM with small (<5 mm) lesions (53%); and ADEM with additional symmetric capsulo-bithalamic involvement (23%). The frequency of patients in each group is similar to that seen by Tenembaum and colleagues,13 with the exception of an increased frequency of thalamic involvement (12% vs 23%), but is strikingly different to the frequency with which large lesions were seen by both Mikaeloff and colleagues22 and the authors’ group25; this may be secondary to the different size cutoff for “large lesions” used by Pavone and colleagues,7 which was not specified. With respect to lesion number, it was noted that all patients had more than 3 identifiable lesions, but no further quantification was made. There was no comment on the specific location of these lesions, with the exception that spinal cord lesions were not identified in any of the patients in this series. Gadolinium enhancement was noted in 18% of the children, with all patients having an open-ring pattern of enhancement.

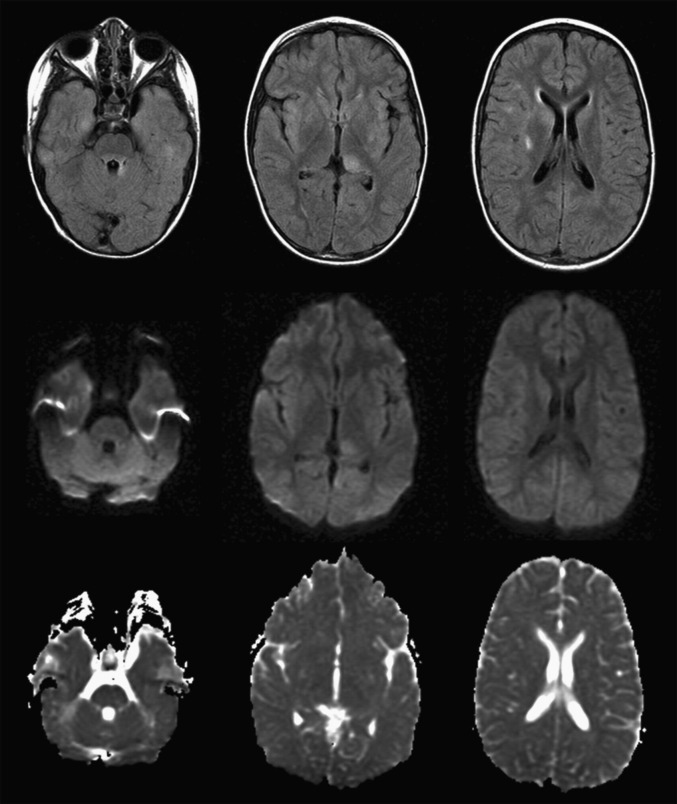

Imaging after a short period of treatment usually shows a decrease in the size and number of lesions and a change in signal intensity of lesions, paralleling clinical improvement (Fig. 6 ). Complete resolution has been noted in up to 70% of patients within months of presentation; however, residual deficits may persist in up to one-third of patients 2 years after ADEM onset.25

Fig. 6.

Resolution of lesions on follow-up imaging. Axial FLAIR (A–C) and T1-weighted images (D–F) at the level of the cerebellar hemispheres (A, D), basal ganglia (B, E) and (C, F) cerebral convexities at time of presentation. Axial FLAIR images (G–I) depicting the same patient weeks after presentation, showing near complete resolution of lesions.

Advanced MR Imaging Modalities

Advanced MR imaging modalities, including magnetization transfer (MY) imaging, diffusion-weighted (DW) imaging, diffusion tensor (DT) imaging, MR spectroscopy, positron emission tomography (PET), and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), have recently been introduced in the diagnostic workup in some settings where there is access to sophisticated neuroimaging. There is increasing literature available on the findings on these modalities in patients with ADEM; however, most studies were completed before the introduction of the new diagnostic criteria for the disorder.

MT imaging

It is widely becoming recognized in MS literature that conventional neuroimaging does not capture the extent of damage of the disorder. With newer imaging modalities, what appeared as “normal appearing” white matter on conventional imaging shows abnormalities on more advanced techniques, such as MT imaging.112 In ADEM it was believed that MT imaging would play a role, particularly early in the disease course at a time when conventional imaging may be unrevealing. However, studies thus far have shown that, unlike in MS, MT imaging fails to reveal abnormalities in normal-appearing brain tissue in these patients.113

DW imaging

Studies investigating the role of DW imaging in patients with ADEM have shown that DW changes are variable and highly dependent on the stage of the disease.103 If DW imaging is completed within the first 7 days of clinical onset, a pattern of restricted diffusion may sometimes be seen, which subsequently changes to a pattern of increased diffusion thereafter.103, 114 Balasubramanya and colleagues103 hypothesized that during the acute stage (within the first 7 days of disease onset), there is swelling of myelin sheaths, reduced vascular supply, and dense inflammatory cell infiltration, which may account for the initial reduced diffusivity, whereas in the subacute stage (after 7 days), demyelination and edema cause expansion of the extracellular space resulting in increased diffusivity. In the authors’ experience, diffusion changes are variable. Most commonly T2 shine-through is seen, rather than true restricted diffusion (Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 7.

Imaging of 4-year-old girl presenting with hallucinations, headaches, and encephalopathy. (Top row) axial FLAIR. (Middle row) Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). (Bottom row) Apparent diffusion coefficient map. Some of the lesions visualized on the FLAIR images are also hyperintense on DWI, but none show restricted diffusion.

DT imaging

Few studies have been completed that investigate the changes on DT imaging in patients with ADEM. Recently, a study suggested that there was reduced fractional anisotropy in a patient with documented active inflammatory demyelination on neuropathology.115 Further studies are needed to delineate the role of DT imaging in patients with ADEM.

MR spectroscopy

An increasing number of studies are being published on the role of MR spectroscopy in ADEM. Similar to findings on DW imaging, the changes on MR spectroscopy appear to be sensitive to the stage of the disease.103, 114, 116, 117 Within the acute phase, an elevation of lipids and reduction of myoinositol/creatinine ratio has been reported, with no change in the N-acetylaspartate (NAA) or choline values.103, 117 As the disease progresses, there is a reduction of NAA and an increase in choline (with corresponding reductions in NAA/creatine and NAA/choline ratios) in regions corresponding to areas of high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging.103, 116 These findings normalize as the clinical and conventional neuroimaging abnormalities resolve. This finding suggests a transient neuroaxonal dysfunction rather than irreversible neuroaxonal loss, and is in contrast to the situation in MS, whereby there is a prompt choline elevation caused by increased levels of the myelin breakdown products, glycerophosphocholine and phosphocholine.116, 118 These changes are also in stark contrast to those seen in intracranial tumors, which is particularly important in patients presenting with a tumefactive demyelinating lesion.

PET and SPECT

In patients with ADEM, studies investigating the role of PET have shown that despite conventional imaging showing only focal demyelinating lesions, there appears to be global and bilateral decreased cerebral metabolism.119 SPECT imaging using 99mTc-HMPAO (d,l-hexamethylpropylene amine oxime) in patients with ADEM have consistently shown areas of hypoperfusion that are more extensive than lesions identified on conventional neuroimaging.120, 121, 122 In one study, persistent cerebral circulatory impairment examined with SPECT using acetazolamide was thought to be a contributing factor to the persistent neurocognitive and language deficits observed in some patients within this cohort.123 Considering that most conventional and unconventional imaging modalities do not seem to find the persistent abnormalities suggested by these studies, further investigation into the clinical role of PET and SPECT in patients with ADEM is warranted.

Differential diagnosis

ADEM can represent a diagnostic challenge for clinicians, as many disorders (inflammatory and noninflammatory) have a similar clinical and radiologic presentation. The differential diagnosis for multifocal hyperintense lesions on neuroimaging includes an exhaustive list of potential mimickers, namely infectious, inflammatory, rheumatologic, metabolic, nutritional and degenerative entities. Despite the significant overlap in clinical and radiologic pictures of many conditions, neuroimaging can aid in narrowing the differential diagnosis.

The first priority in a patient presenting with neurologic signs and symptoms and encephalopathy, particularly in the presence of a preceding febrile illness, is to rule out bacterial or viral infection of the CNS. Therefore, a lumbar puncture and MR imaging should be completed as soon as possible and empiric antimicrobial therapy should be considered. A lumbar puncture will likely provide the most important diagnostic clues of an infective process, but neuroimaging can also play a role. A diagnosis of meningoencephalitis can be suggested by leptomeningeal enhancement on postcontrast imaging (which is not a feature of ADEM) or stereotypical involvement of limbic structures in the case of limbic encephalitis.

After neuroimaging has been completed, the findings at the time of initial presentation may be useful. If a large tumor-like lesion is present in addition to tumefactive ADEM or MS, one should consider a benign or malignant tumor, one of the MS variants (including Schilder124 and Marburg125 variants), or brain abscess depending on the clinical picture. The differentiation of ADEM from tumor becomes particularly difficult in the case of ADEM-related brainstem lesions, as they are commonly associated with edema and can be easily misdiagnosed as a malignant process. In the case of tumefactive demyelination, it has been suggested that a combination of open-ring enhancement, peripheral restriction on DW imaging, venular enhancement, and presence of glutamine/glutamate (Glx) levels on MR spectroscopy may be helpful in differentiating ADEM from neoplastic lesions.126

If there is bithalamic involvement, in addition to ADEM with this radiologic representation (particularly in the case of ADEM after Japanese B encephalitis127) one should consider mitochondrial disorders (particularly Leigh syndrome), deep cerebral vein thrombosis, hypernatremia, Reye syndrome, Sandoff disease, and acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood (ANEC), depending on the clinical picture. ANEC, which has mainly been described in Japan, Taiwan, and Korea, is an acute encephalopathy following 2 to 4 days of gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms and fever.128 Neuroimaging findings include multifocal, symmetric brain lesions involving the thalami, cerebral or cerebellar white matter, and brainstem.128, 129 Basal ganglia involvement, which is common in ADEM (particularly poststreptococcal ADEM130), may be consistent with many processes: for example, organic acidurias, mitochondrial disorders (particularly Leigh syndrome), and Wilson disease.

Another diagnostic consideration with a similar clinical presentation is posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). Although typically induced by hypertension, seizures, or immunosuppressants, a history of a preceding inciting factor may be lacking. PRES presents with reversible white matter edema that may or may not have a posterior predominance.

The enhancement pattern of the lesions may also suggest alternative diagnoses. Although ring enhancement has been reported in ADEM, one should consider brain abscess, tuberculomas, neurocystercosis, toxoplasmosis, or histoplasmosis, depending on the history.131

One of the most difficult differentiations is between ADEM and other demyelinating disorders, namely MS. The authors attempted to describe means by which patients with ADEM could be differentiated from patients with MS based on their radiologic findings.25 Previous descriptive studies in which the MR imaging appearances of patients with ADEM were compared with MR imaging scans obtained during the first attack of MS determined that these two clinical scenarios could not reliably be distinguished. After retrospective analysis of MR imaging scans at first attack in 28 children with MS and 20 children with ADEM, the following criteria were reliable in distinguishing patients with MS from those with ADEM, with a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 95%: any 2 of (1) absence of diffuse bilateral lesion pattern, (2) presence of black holes, and (3) presence of 2 or more periventricular lesions.25

Treatment

There is no standard treatment regimen for ADEM. Most of the data describing the treatment of patients with ADEM are derived from case reports and some small series. To date, no randomized controlled trials for treatment of ADEM have been completed in either the pediatric or adult population. Most treatment approaches use some form of nonspecific immunosuppressant therapy, including corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), or plasmapheresis. There are no studies comparing the efficacy of the different immunomodulatory therapies.

Corticosteroids are the most widely used and most ubiquitously reported therapy for patients with ADEM. In a recently proposed algorithm for treatment in ADEM, steroids were considered the first line in therapy.132 Throughout the literature, there is great variation in the dose and formulation of steroids used, the routes of administration followed (oral or intravenous), and tapering regimens described. Most groups use steroids at very high doses. The most commonly used treatment protocols include intravenous methylprednisolone, 10 to 30 mg/kg/d up to a maximum daily dose of 1 g or dexamethasone (1 mg/kg) for 3 to 5 days followed by an oral steroid taper over 4 to 6 weeks.3, 8, 9, 13, 133 There is some suggestion in comparative studies that methylprednisolone-treated patients had significantly better Expanded Disability Status Scale scores after treatment than those administered dexamethasone.13 It has also been reported that there is an increased risk of relapse with steroid tapers of less than 3 weeks.8, 14 Corticosteroids are very effective for symptom resolution in ADEM, with 50% to 80% of patients having a full recovery.8, 9, 13 Recovery is typically seen over a few days, with the more severely affected patients requiring weeks or months for recuperation. Despite their efficacy, steroids are not without risk. Side effects of corticosteroids include gastric hemorrhage and perforation, hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, hypertension, facial flushing, and mood lability, even with short-term use. Therefore, it is advisable to administer gastric protective measures during the short period that patients are being treated with corticosteroids.

There are multiple case reports of successful use of IVIg, either alone,134, 135 in combination with corticosteroids,136 after failed intravenous pulse steroids,137, 138, 139 or in recurrent demyelination.69, 140 The reported dosing for IVIg is more consistent than that for steroids, with a total dose of 1 to 2 g/kg as a single dose or over 3 to 5 days. IVIg is generally well tolerated.

Plasmapheresis theoretically works to remove autoantibodies that are presumably triggering demyelination seen in ADEM, or to shift the dynamics of the interactions of B and T cells within the immune system. Its use has been reported in several case studies, typically in severe cases of ADEM when steroid treatment has failed. Complete recovery has been reported in some patients with ADEM.141, 142, 143 In patients with CNS demyelination (including patients with ADEM), 40% had moderate to marked improvement following a mean number of 7 exchanges.144 It has been suggested that plasmapheresis is more effective when given early in the course.145 Unfortunately, it is often used as a last resort, owing to the resources needed for treatment implementation. Side effects noted include hypotension, anemia, and headache.

Patients with ADEM have been symptomatically managed with decompressive hemicraniectomy as a life-saving measure when there is massive cerebral edema that is refractory to medical management; however, this is an uncommon scenario.146, 147

Prognosis

ADEM has a monophasic course in 70% to 90% of cases.7, 8, 9, 13, 15, 22, 61, 148, 149, 150, 151 Typically prognosis is excellent in patients with ADEM.8, 13 In previous studies, a full recovery has been noted in approximately 70% to 90% of patients, characteristically within 6 months of onset.3, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Studies including patients who meet criteria according to Krupp and colleagues18 have shown similar results.7, 22, 26 Severe complications (including death) are rare in the pediatric population,14, 26, 152 unless measles is the inciting factor.62, 153, 154 The most common focal neurologic deficits following ADEM include focal motor deficits (ranging from mild clumsiness to hemiparesis), visual impairment, behavioral or cognitive problems, or epilepsy.93 However, more recently there has been increased awareness regarding the frequency of behavioral and subtle neurocognitive deficits in patients with a previous diagnosis of ADEM. Subtle neurocognitive deficits have been identified in attention, executive function, and behavior when evaluated years after ADEM in up to 50% to 60% of patients.7, 155, 156, 157 These effects appear to be more prominent in patients who have a younger age of onset (<5 years).155

Variants

More aggressive variants of ADEM have been described in the literature, including acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis, acute hemorrhagic encephalomyelitis, and acute necrotizing hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis of Weston Hurst. All of these variants describe hyperacutely presenting, rapidly progressive, fulminant inflammatory and hemorrhagic demyelinating disorders of the CNS that are usually triggered by an upper respiratory tract infection. In one large cohort, these hemorrhagic variants had been described in 2% of patients with ADEM.13 On MR imaging, lesions tend to be large, with perilesional edema and mass effect.158, 159 Death had previously been described in a majority of these patients within 1 week of onset; however, there is increasing evidence of favorable outcomes if early and aggressive treatment with immunomodulatory agents is used.13, 160, 161, 162 These variants are covered in more detail elsewhere in this issue.

ADEM has a monophasic course in a majority of patients; however, recurrent and multiphasic cases have been documented.8, 9, 13, 15, 22, 61, 148, 149, 150, 151 As such, the International Pediatric MS Study Group18 also proposed a consensus definition for recurrent ADEM (RADEM) and multiphasic ADEM (MADEM). The difference between recurrent and multiphasic ADEM hinges on whether there is involvement of a new brain region, as suggested by clinical history, examination, or neuroimaging (MADEM), or if there is recapitulation of the prior illness (RADEM). As with the first episode, polyfocal clinical symptoms and encephalopathy are mandatory.

Notwithstanding the new consensus definitions for RADEM and MADEM, there continues to be controversy regarding the existence of these entities, as the monophasic course of ADEM is considered by some to be a hallmark of this disorder. The rates of these entities reported in the literature have varied depending on the ADEM definition used, the period of inclusion or follow-up, and the study design. Considering that previous studies used dissimilar definitions of ADEM (which differ from the definition proposed), it may be that the inclusion of patients with monofocal presentation or those lacking encephalopathy will bias these studies toward describing a fundamentally different cohort. In addition, in the studies describing recurrent and multiphasic cases of ADEM, different diagnostic criteria for relapses were used. As the new definition for ADEM states that any new symptoms within 3 months from onset should be considered part of the initial attack, it is likely that some of the patients deemed to have relapsed may no longer meet criteria for either multiphasic or relapsing ADEM.18

Despite these issues, previously reported rates of a recurrent or multiphasic course have ranged from 5% to 30%.3, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Since implementation of the new consensus criteria, 3 studies have commented on recurrence rates in patients with ADEM. Visudtibhan and colleagues26 followed their patients for a mean of 5.8 years and ultimately diagnosed 3 of 15 children with MS. None were diagnosed with MADEM or RADEM by the end of the follow-up period.26 Mikaeloff and colleagues22 found a recurrence rate in 18% of their patients after a mean follow-up period of 5.4 ± 3.3 years. All of these patients were noted to have a second attack at a different site in the CNS. An increased risk of a second attack has been associated with previous demyelination episodes in the family, first presentation with optic neuritis, fulfilling MS Barkoff criteria on initial neuroimaging, and absence of sequelae after the acute episode.22 Considering that the first 3 risk factors are known predictive factors for further relapses in MS, it was surmised that this strengthened the link between relapsing disease after ADEM onset and MS.22 The final study by Pavone and colleagues7 found a relapse rate of 12% after a follow-up period ranging from 4.4 to 17.1 years. It is not clear whether these patients would have met criteria for either RADEM or MADEM considering that the presence of encephalopathy was not noted in either patient, nor was the location of their lesions on MR imaging. Considering the results of these 3 studies, it may be that Mikaeloff and colleagues22 were correct in suggesting a strong link between recurrent ADEM and MS. Long-term prospective follow-up studies of patients diagnosed with ADEM by the new consensus criteria will provide important information regarding the natural history of ADEM and its potential relationship with MS.

References

- 1.Nasr J.T., Andriola M.R., Coyle P.K. ADEM: literature review and case report of acute psychosis presentation. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;22:8–18. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(99)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khong P.L., Ho H.K., Cheng P.W. Childhood acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: the role of brain and spinal cord MRI. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s00247-001-0582-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupte G., Stonehouse M., Wassmer E. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a review of 18 cases in childhood. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:336–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caldemeyer K.S., Smith R.R., Harris T.M. MRI in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:216–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00588134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi A. Imaging of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2008;18:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2007.12.007. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menge T., Hemmer B., Nessler S. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: an update. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1673–1680. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.11.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavone P., Pettoello-Mantovano M., Le Pira A. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a long-term prospective study and meta-analysis. Neuropediatrics. 2010;41:246–255. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1271656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dale R.C., de Sousa C., Chong W.K. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis in children. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 12):2407–2422. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hynson J.L., Kornberg A.J., Coleman L.T. Clinical and neuroradiologic features of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children. Neurology. 2001;56:1308–1312. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz S., Mohr A., Knauth M. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a follow-up study of 40 adult patients. Neurology. 2001;56:1313–1318. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leake J.A., Albani S., Kao A.S. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in childhood: epidemiologic, clinical and laboratory features. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:756–764. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000133048.75452.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murthy S.N., Faden H.S., Cohen M.E. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e21. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tenembaum S., Chamoles N., Fejerman N. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a long-term follow-up study of 84 pediatric patients. Neurology. 2002;59:1224–1231. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.8.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anlar B., Basaran C., Kose G. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children: outcome and prognosis. Neuropediatrics. 2003;34:194–199. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikaeloff Y., Suissa S., Vallee L. First episode of acute CNS inflammatory demyelination in childhood: prognostic factors for multiple sclerosis and disability. J Pediatr. 2004;144:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung K.L., Liao H.T., Tsai M.L. The spectrum of postinfectious encephalomyelitis. Brain Dev. 2001;23:42–45. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(00)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Idrissova Zh R., Boldyreva M.N., Dekonenko E.P. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children: clinical features and HLA-DR linkage. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krupp L.B., Banwell B., Tenembaum S. Consensus definitions proposed for pediatric multiple sclerosis and related disorders. Neurology. 2007;68:S7–S12. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259422.44235.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richer L.P., Sinclair D.B., Bhargava R. Neuroimaging features of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in childhood. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madan S., Aneja S., Tripathi R.P. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis—a case series. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singhi P.D., Ray M., Singhi S. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in North Indian children: clinical profile and follow-up. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:851–857. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210100201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikaeloff Y., Caridade G., Husson B. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis cohort study: prognostic factors for relapse. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2007;11:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atzori M., Battistella P.A., Perini P. Clinical and diagnostic aspects of multiple sclerosis and acute monophasic encephalomyelitis in pediatric patients: a single centre prospective study. Mult Scler. 2009;15:363–370. doi: 10.1177/1352458508098562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alper G., Heyman R., Wang L. Multiple sclerosis and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis diagnosed in children after long-term follow-up: comparison of presenting features. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:480–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callen D.J., Shroff M.M., Branson H.M. Role of MRI in the differentiation of ADEM from MS in children. Neurology. 2009;72:968–973. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338630.20412.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Visudtibhan A., Tuntiyathorn L., Vaewpanich J. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a 10-year cohort study in Thai children. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2010;14:513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torisu H., Kira R., Ishizaki Y. Clinical study of childhood acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, and acute transverse myelitis in Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan. Brain Dev. 2010;32:454–462. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banwell B., Kennedy J., Sadovnick D. Incidence of acquired demyelination of the CNS in Canadian children. Neurology. 2009;72:232–239. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339482.84392.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khurana D.S., Melvin J.J., Kothare S.V. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children: discordant neurologic and neuroimaging abnormalities and response to plasmapheresis. Pediatrics. 2005;116:431–436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suppiej A., Vittorini R., Fontanin M. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children: focus on relapsing patients. Pediatr Neurol. 2008;39:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weng W.C., Peng S.S., Lee W.T. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children: one medical center experience. Acta Paediatr Taiwan. 2006;47:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin C.H., Jeng J.S., Hsieh S.T. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a follow-up study in Taiwan. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:162–167. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.084194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jayakrishnan M.P., Krishnakumar P. Clinical profile of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2010;5:111–114. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.76098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daoud E., Chabchoub I., Neji H. How MRI can contribute to the diagnosis of acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis in children. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2011;16:137–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marchioni E., Ravaglia S., Piccolo G. Postinfectious inflammatory disorders: subgroups based on prospective follow-up. Neurology. 2005;65:1057–1065. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000179302.93960.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amit R., Shapira Y., Blank A. Acute, severe, central and peripheral nervous system combined demyelination. Pediatr Neurol. 1986;2:47–50. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(86)90040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amit R., Glick B., Itzchak Y. Acute severe combined demyelination. Childs Nerv Syst. 1992;8:354–356. doi: 10.1007/BF00296569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadkarni N., Lisak R.P. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) with bilateral optic neuritis and central white matter disease. Neurology. 1993;43:842–843. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wingerchuk D.M. Postinfectious encephalomyelitis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2003;3:256–264. doi: 10.1007/s11910-003-0086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Absoud M., Parslow R., Wassmer E. Severe acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a paediatric intensive care population-based study. Mult Scler. 2011;17:1258–1261. doi: 10.1177/1352458510382554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rivers T.M., Sprunt D.H., Berry G.P. Observations on attempts to produce acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in monkeys. J Exp Med. 1933;58:39–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.58.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rivers T.M., Schwentker F.F. Encephalomyelitis accompanied by myelin destruction experimentally produced in monkeys. J Exp Med. 1935;61:689–702. doi: 10.1084/jem.61.5.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wucherpfennig K.W., Strominger J.L. Molecular mimicry in T cell-mediated autoimmunity: viral peptides activate human T cell clones specific for myelin basic protein. Cell. 1995;80:695–705. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tejada-Simon M.V., Zang Y.C., Hong J. Cross-reactivity with myelin basic protein and human herpesvirus-6 in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:189–197. doi: 10.1002/ana.10425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Talbot P.J., Paquette J.S., Ciurli C. Myelin basic protein and human coronavirus 229E cross-reactive T cells in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:233–240. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Markovic-Plese S., Hemmer B., Zhao Y. High level of cross-reactivity in influenza virus hemagglutinin-specific CD4+ T-cell response: implications for the initiation of autoimmune response in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;169:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lang H.L., Jacobsen H., Ikemizu S. A functional and structural basis for TCR cross-reactivity in multiple sclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:940–943. doi: 10.1038/ni835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pohl-Koppe A., Burchett S.K., Thiele E.A. Myelin basic protein reactive Th2 T cells are found in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;91:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jorens P.G., VanderBorght A., Ceulemans B. Encephalomyelitis-associated antimyelin autoreactivity induced by streptococcal exotoxins. Neurology. 2000;54:1433–1441. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.7.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ubol S., Hemachudha T., Whitaker J.N. Antibody to peptides of human myelin basic protein in post-rabies vaccine encephalomyelitis sera. J Neuroimmunol. 1990;26:107–111. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90081-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Connor K.C., Chitnis T., Griffin D.E. Myelin basic protein-reactive autoantibodies in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients are characterized by low-affinity interactions. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;136:140–148. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lipton H.L. Theiler's virus infection in mice: an unusual biphasic disease process leading to demyelination. Infect Immun. 1975;11:1147–1155. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.5.1147-1155.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller S.D., Vanderlugt C.L., Begolka W.S. Persistent infection with Theiler's virus leads to CNS autoimmunity via epitope spreading. Nat Med. 1997;3:1133–1136. doi: 10.1038/nm1097-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clatch R.J., Lipton H.L., Miller S.D. Characterization of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity responses in TMEV-induced demyelinating disease: correlation with clinical signs. J Immunol. 1986;136:920–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ichiyama T., Shoji H., Kato M. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of cytokines and soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:133–137. doi: 10.1007/s00431-001-0888-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ichiyama T., Kajimoto M., Suenaga N. Serum levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and its tissue inhibitor (TIMP-1) in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;172:182–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Franciotta D., Zardini E., Ravaglia S. Cytokines and chemokines in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of adult patients with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson R.T. The pathogenesis of acute viral encephalitis and postinfectious encephalomyelitis. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:359–364. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stuve O., Zamvil S.S. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Curr Opin Neurol. 1999;12:395–401. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kanzaki A., Yabuki S. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) associated with cytomegalovirus infection–a case reportRinsho Shinkeigaku. 1994;34:511–513. [in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shoji H., Kusuhara T., Honda Y. Relapsing acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection: MRI findings. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:340–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00588198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnson R.T., Griffin D.E., Hirsch R.L. Measles encephalomyelitis—clinical and immunologic studies. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:137–141. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198401193100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saitoh A., Sawyer M.H., Leake J.A. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with enteroviral infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:1174–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.El Ouni F., Hassayoun S., Gaha M. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following herpes simplex encephalitis. Acta Neurol Belg. 2010;110:340–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tullu M.S., Patil D.P., Muranjan M.N. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in a child presenting as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. J Child Neurol. 2011;26:99–102. doi: 10.1177/0883073810375717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Narciso P., Galgani S., Del Grosso B. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis as manifestation of primary HIV infection. Neurology. 2001;57:1493–1496. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.8.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sawanyawisuth K., Phuttharak W., Tiamkao S. MRI findings in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following varicella infection in an adult. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:1230–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang G.F., Li W., Li K. Acute encephalopathy and encephalitis caused by influenza virus infection. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:305–311. doi: 10.1097/wco.0b013e328338f6c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Revel-Vilk S., Hurvitz H., Klar A. Recurrent acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with acute cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:421–424. doi: 10.1177/088307380001500614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Igarashi K., Kajino M., Shirai M. A case of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with Epstein-Barr virus infectionNo To Hattatsu. 2011;43:59–61. [in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tselis A.C., Lisak R.P. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In: Antel J.P., Birnbaum G., Hartung H.P., editors. Clinical neuroimmunology. 2nd edition. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, USA: 2005. pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hall M.C., Barton L.L., Johnson M.I. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis-like syndrome following group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:354–356. doi: 10.1177/088307389801300711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ning M.M., Smirnakis S., Furie K.L. Adult acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with poststreptococcal infection. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:298–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Budan B., Ekici B., Tatli B. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) after pertussis infection. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2011;31:269–272. doi: 10.1179/1465328111Y.0000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Easterbrook P.J., Smyth E.G. Post-infectious encephalomyelitis associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila infection. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68:124–128. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.68.796.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hagiwara H., Sakamoto S., Katsumata T. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis developed after Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicating subclinical measles infection. Intern Med. 2009;48:479–483. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van Assen S., Bosma F., Staals L.M. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with Borrelia burgdorferi. J Neurol. 2004;251:626–629. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0415-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.de Lau L.M., Siepman D.A., Remmers M.J. Acute disseminating encephalomyelitis following Legionnaires disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:623–626. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wei T.Y., Baumann R.J. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis after Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Pediatr Neurol. 1999;21:503–505. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(99)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van der Wal G., Verhagen W.I., Dofferhoff A.S. Neurological complications following Plasmodium falciparum infection. Neth J Med. 2005;63:180–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hemachudha T., Griffin D.E., Giffels J.J. Myelin basic protein as an encephalitogen in encephalomyelitis and polyneuritis following rabies vaccination. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:369–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198702123160703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hemachudha T., Griffin D.E., Johnson R.T. Immunologic studies of patients with chronic encephalitis induced by post-exposure Semple rabies vaccine. Neurology. 1988;38:42–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sejvar J.J., Labutta R.J., Chapman L.E. Neurologic adverse events associated with smallpox vaccination in the United States, 2002-2004. JAMA. 2005;294:2744–2750. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.21.2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bomprezzi R., Wildemann B. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following vaccination against human papilloma virus. Neurology. 2010;74:864. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d2b508. [author reply: 864–5] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shoamanesh A., Traboulsee A. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following influenza vaccination. Vaccine. 2011;29:8182–8185. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Denholm J.T., Neal A., Yan B. Acute encephalomyelitis syndromes associated with H1N1 09 influenza vaccination. Neurology. 2010;75:2246–2248. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182020307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takahashi H., Pool V., Tsai T.F. Adverse events after Japanese encephalitis vaccination: review of post-marketing surveillance data from Japan and the United States. The VAERS Working Group. Vaccine. 2000;18:2963–2969. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ozawa H., Noma S., Yoshida Y. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with poliomyelitis vaccine. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;23:177–179. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(00)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tourbah A., Gout O., Liblau R. Encephalitis after hepatitis B vaccination: recurrent disseminated encephalitis or MS? Neurology. 1999;53:396–401. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.2.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Karaali-Savrun F., Altintas A., Saip S. Hepatitis B vaccine related-myelitis? Eur J Neurol. 2001;8:711–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Py M.O., Andre C. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and meningococcal A and C vaccine: case reportArq Neuropsiquiatr. 1997;55:632–635. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1997000400020. [in Portuguese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Murphy J., Austin J. Spontaneous infection or vaccination as cause of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neuroepidemiology. 1985;4:138–145. doi: 10.1159/000110225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tenembaum S., Chitnis T., Ness J. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neurology. 2007;68:S23–S36. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259404.51352.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fenichel G.M. Neurological complications of immunization. Ann Neurol. 1982;12:119–128. doi: 10.1002/ana.410120202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Garg R.K. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:11–17. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.927.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Horowitz M.B., Comey C., Hirsch W. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) or ADEM-like inflammatory changes in a heart-lung transplant recipient: a case report. Neuroradiology. 1995;37:434–437. doi: 10.1007/BF00600082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Re A., Giachetti R. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:1351–1354. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Oh H.H., Kwon S.H., Kim C.W. Molecular analysis of HLA class II-associated susceptibility to neuroinflammatory diseases in Korean children. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:426–430. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.3.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alves-Leon S.V., Veluttini-Pimentel M.L., Gouveia M.E. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: clinical features, HLA DRB1*1501, HLA DRB1*1503, HLA DQA1*0102, HLA DQB1*0602, and HLA DPA1*0301 allelic association study. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2009;67:643–651. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2009000400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pohl D., Rostasy K., Reiber H. CSF characteristics in early-onset multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63:1966–1967. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000144352.67102.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Franciotta D., Columba-Cabezas S., Andreoni L. Oligoclonal IgG band patterns in inflammatory demyelinating human and mouse diseases. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;200:125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Baum P.A., Barkovich A.J., Koch T.K. Deep gray matter involvement in children with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:1275–1283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Balasubramanya K.S., Kovoor J.M., Jayakumar P.N. Diffusion-weighted imaging and proton MR spectroscopy in the characterization of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neuroradiology. 2007;49:177–183. doi: 10.1007/s00234-006-0164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Brinar V.V., Habek M. Monophasic acute, recurrent, and multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:675–676. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.5.675. [author reply: 676] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brinar V.V., Habek M. Diagnostic imaging in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:459–467. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kesselring J., Miller D.H., Robb S.A. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. MRI findings and the distinction from multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1990;113(Pt 2):291–302. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mader I., Stock K.W., Ettlin T. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: MR and CT features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:104–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Panicker J.N., Nagaraja D., Kovoor J.M. Descriptive study of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and evaluation of functional outcome predictors. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:12–16. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.62425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Singh S., Alexander M., Korah I.P. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: MR imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:1101–1107. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.4.10511187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Singh S., Prabhakar S., Korah I.P. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis: magnetic resonance imaging differentiation. Australas Radiol. 2000;44:404–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.2000.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Verhey L.H., Branson H.M., Shroff M.M. MRI parameters for prediction of multiple sclerosis diagnosis in children with acute CNS demyelination: a prospective national cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(12):1065–1073. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Filippi M., Tortorella C., Rovaris M. Changes in the normal appearing brain tissue and cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:157–161. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Inglese M., Salvi F., Iannucci G. Magnetization transfer and diffusion tensor MR imaging of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:267–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]